Zoning for Gloomy Days: How the Ironbound was Designed to Oppress Child Development

by Catrina Nelson

Site Description:

In the Ironbound district of Newark, NJ, there is a long history of land zoned for industrial use, such as factories, incinerators and an airport, all while being adjacent to schools, and multifamily housing. There is also a severe lack of access to green space and parks available to its residents, especially considering how densely packed the population is. By studying the zoning plans of 1964, 1978 and today, we can trace how the district was designed to compromise the quality of life for the largely hispanic community, and especially how this jeopardizes the development of their children. Toxic pollution compromising their health, noise pollution compromising their ability to learn in school, and few, far places to play, all add up and contribute to the outcome of the most vulnerable residents of the Ironbound. When a neighborhood is safe for children, it is safe for all residents. By examining these root of these effects, we can better understand how to improve the landscape for the many children growing up in the Ironbound, and the quality of life for everyone connected with that child, including parents, teachers and the elderly.

How has zoning consequences in the Ironbound District created a landscape that places outweighing burdens on the development of children, ultimately impacting the community as a whole?

Final Report:

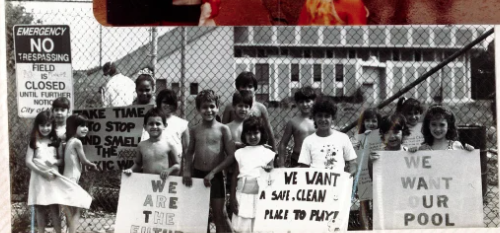

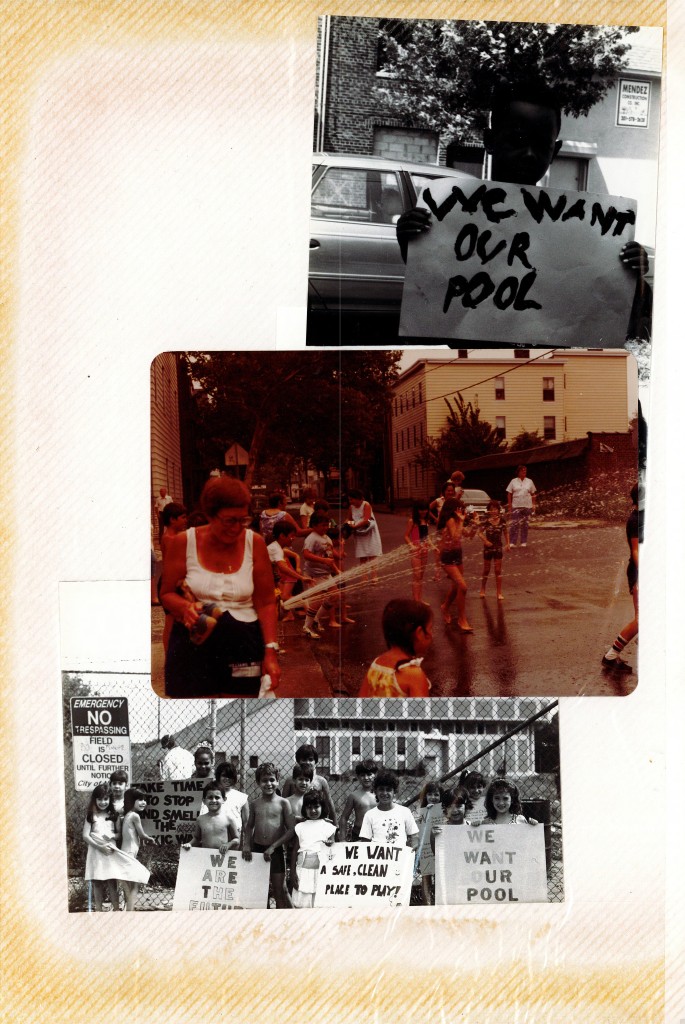

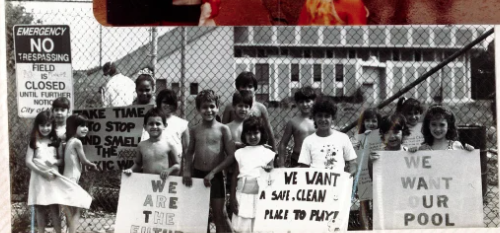

“We want a safe clean place to play!”

The message, conveyed in dark letters on a bright white poster, with faint smiling stars surrounding the words, was held up proudly by a protester. He was standing next to his sister, also holding the poster in hand, and together they were surrounded by many fellow radicals. They were gathered in front of a chain link fence, the only barrier between them and the Wilson Ave. Bathhouse.

“We want our pool!”

“We are the future”

“Take time to stop and smell the toxic waste.”

The year was 1980, and their handmade signs were calling for the city of Newark to take responsibility for closing a beloved community resource, the Wilson Ave. Bathhouse. Although the protesters directly felt the impact of what was removed from their neighborhood, what was more striking was that they were no older than eleven years old. The Bathhouse used to be located in the Ironbound, a neighborhood in Newark, New Jersey. Eventually the site, which was adjacent to an elementary school, was sold to developers who wanted to build more housing[1]. This incident is one of many, in the timeline of the neighborhood that demonstrates the city prioritizing development at the cost of neglecting to care for cherished spaces used by children.

When viewing the Ironbound from above, the grey ocean of densely packed houses and large swaths of industrial land is sparsely broken up by tiny patches of parks for the community of over 50,000 residents.[2] It calls to question how the landscape became dominated by gritty terrain with so few places designated for children? Even while walking past several of the elementary schools in the area, there is noticeably little space for the hundreds of children to play for recess. Residents do not need to wonder how these industrial sites impact their health and quality of life. The answers are tucked away from public speculation, hidden in the office of the local government offices. Officials in Newark intentionally made decisions about the landscape of the Ironbound neighborhood that not only prioritized development, but in consequence impaired child development, especially from the 1950s to the early 2000s.

To understand the injustice children in the Ironbound experience, it is important to first briefly cover contextual information about this era of in city of Newark. This will draw out the historical influences that led to the creation of the 1964 Master Plan, as well as other significant planning decisions along the way. It will examine how the city prioritized its industrial economy and prioritized intense development of its transportation system. These decisions negatively impact children’s cognitive performance, as well as their health. To further consider planning decisions that impacted children, it is important to inspect the land that is designated for them, such as parks and schools, particularly surveying their inadequate property sizes. Additionally, there have been city made plans to remove community resources that were valuable to children, such as the Wilson Avenue Bathhouse. Finally, after pulling out the consequences of decades of neglect, it is vital to propose some potential solutions that can bridge the gap between living in an urban context, and needing sufficient space and resources for play. The implications of city planned choices in the Ironbound disenfranchised one of the most vulnerable groups in society, impacting their development and quality of life.

The Ironbound Neighborhood and Newark’s 1964 Master Plan

Newark, New Jersey sits about five miles to the west of New York City, and is part of its greater metropolitan area. Newark’s boundary is defined by the Passaic River curving in all four directions. The Ironbound is Newark’s farthest east neighborhood and sits between the Passaic River to its north, with the Newark Liberty International Airport to its south. The foundation of Newark steamed during the industrial revolution, and still remains an industrious city, with the Ironbound being the backbone that is home to many industrial sites. Moreover, the Ironbound neighborhood has been built up by a working-class community, pulsing with vibrant culture from its majority immigrant residents.

In 1930, the city’s population peaked with 438,776 residents, however beginning in the 1950s, Newark saw a large shift in its demographics.[3] Like many other industrial cities at this time, Newark saw most of its white, wealthier residents move out to the suburbs to avoid the unpleasant aspects of urban life, including high crime and high density of population.[4] In exchange, African Americans, and particularly Portuguese in the Ironbound, were able to afford the low housing prices. Additionally, the 1967 riots that shook the core of the city, as well as escalated racial tension and political corruption, exacerbated this outward flow of the wealthy, while the poor settled in its place.[5] Overall, from 1950 to 1990 over 160,000 people left the city, a decrease of 38%.[6]

With a significant outward migration, left in its place a series of vacant land and demolished houses. In response to the condition of the city, the local government proposed an updated master plan for Newark in 1964. A city master plan is a document written by the local government that reviews the existing landscape, and offers strategies and goals that addresses its city’s needs and demands of residents. The municipality writes the official guide to instruct development. These changes can be presented in the form of local laws and policies, but typically the changes happen through the physical environment, by means of infrastructure and zoning land-uses.[7] The 1964 Master Plan is significant for the context of this discussion because it has been published during the midst of a great “large-scale reconstruction and revitalization” in Newark, between the 1960s and the early 2000s.[8]

In the master plan, there are numerous informative maps about the landscape, and the one above introduces the existing land use map of Newark in 1964, but specifically highlights the Ironbound. This neighborhood had “intensive industrial uses”, which are found “interspersed with residential uses.” [9] This containment of family homes and toxic industrial plants leaves residents battling the long-term health effects. In the master plan, one of the city’s main goals is to “stimulate industrial growth” and “the provision of industrial land for new industries or for the expansion of existing industries”.[10] Over the few decades following the document, city officials voted to expand industrial development at the cost of its residents’ health, and particularly its children’s health.[11]

Ironbound Children in Danger

In 1985, the residents of the Ironbound fought tooth and nail against this industrial development, vocalizing their concerns about the construction of another garbage incinerator. On April 10th of that year, more than 500 residents, from all ages, went to City Hall to demand the city council to vote NO to the incinerator. June Kruszewski tried to plead with the council officials, “Don’t our lives and our children’s lives count?”. Unfortunately, their voices went unheard, and less than two weeks later, the Newark City Council voted against the people in the Ironbound, approving construction of the poisonous incinerator. Denis Cabados, a lifelong Ironbound resident, said “Most of us here are poor. We cannot afford to move somewhere else. We live here 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and we have to live with the pollution that’s already here. I want my children to grow up healthy”. It’s true, those that will feel the greatest impact of the incinerator are the children. Nicole Taylor, who was a 6th grade student at the time, said she “wants to grow up normal and healthy”. [12]

A teacher at a public school in the Ironbound, Mr. Woodward, expressed that his students were fearful after the public hearing about the garbage incinerator, and they expressed feeling hopeless about the impending diseases that the pollution could cause them.[13] In a study conducted by Sweden, dioxin, an environmental pollutant, was found in breast milk. This in turn causes babies to absorb very high levels of dioxin. Dioxin is cancerous and lowers the immune system, making babies and vulnerable children more susceptible to illness.[14] [15] Furthermore, an even worse epidemic for the children of the Ironbound is chronic asthma. There “about one in every four children in Newark has asthma, a rate three times higher than the national average, and those children are hospitalized for asthma at 30 times the national rate”.[16] Leland Sewell, born in Newark in 2009, was premature with underdeveloped lungs, and he later died because of a severe asthma attack, at only seven years old. He, along with all his young classmates, breath in polluted air everyday due to the nearby incinerators and industrial plants.[17] By promoting industrial growth and voting to construct an incinerator in a densely populated neighborhood, the city of Newark caused thousands of children over many decades to suffer from chronic illness and even death.[18]

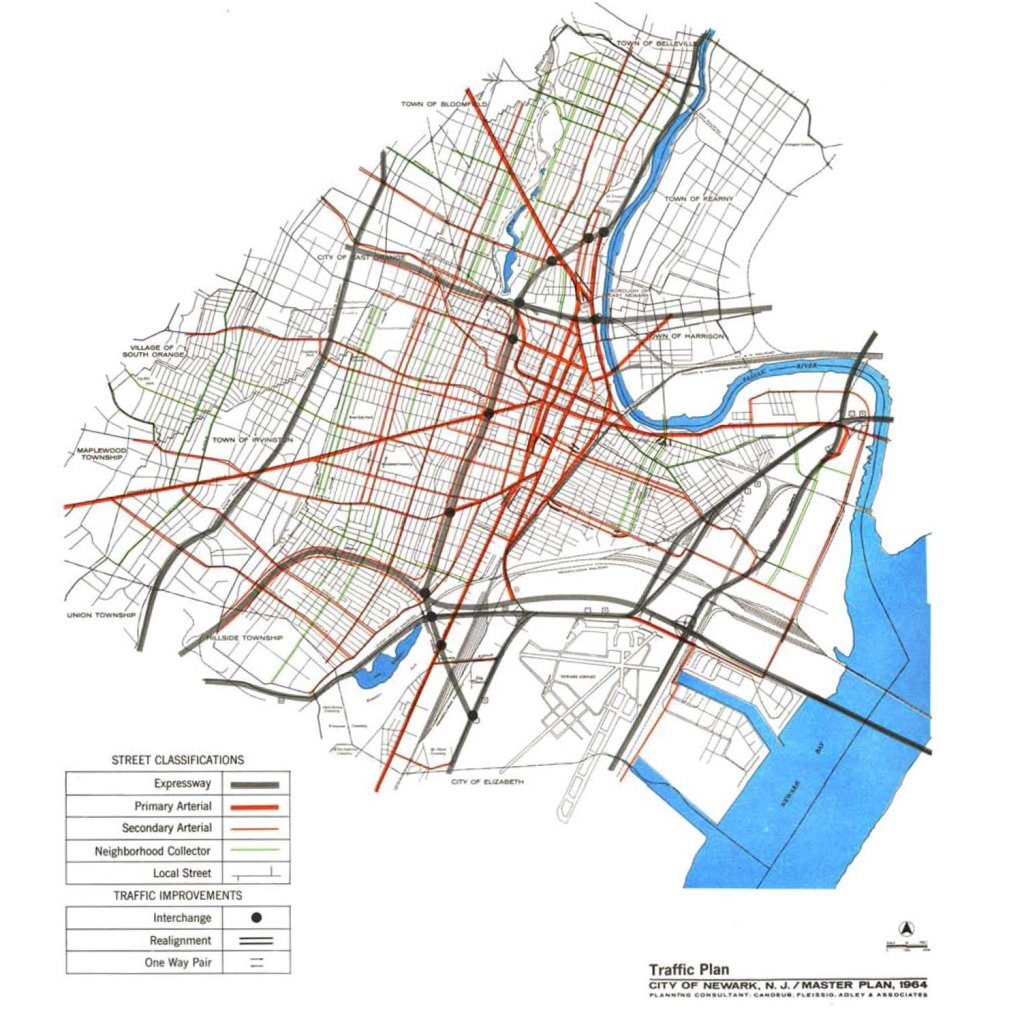

Additionally, what follows in the footsteps of the incinerator are the rotten garbage trucks. This means, in addition to the imminent toxic pollution, residents also faced a large influx of traffic through their streets. However, this traffic surge did not grow incidentally after the incinerator was constructed. The origin of the surge was in the 1950s through the 1970s, with construction of three large highways; Route 78, Route 280 and the Garden State Parkway. This infrastructure “sliced through portions of Newark and disrupted the continuity of established neighborhoods.”[19] The highways were planned in relation to the outward migration of wealthier residents, to provide them a route to inner cities, without consideration for the consequential effects to the residents that actually live there. Below are street plans proposed by the city in the Master Plan. The Ironbound itself is contained by major routes of travel, with Raymond Blvd. to its north, McCarter Highway to its west, US route 1-9 to its south and east, and the Pennsylvania Railroad to its south, west and east.[20] In fact, the name “ironbound” is derived from these conditions; the neighborhood is bounded by iron railroads. To add to the prevailing traffic, there is also an international airport, barely a mile to the neighborhood’s south, with air traffic flying overhead at every hour of the day

Proposed Street Hierarchy Map, Taken from the 1964 Master Plan

Newark’s Noise Pollution Problem

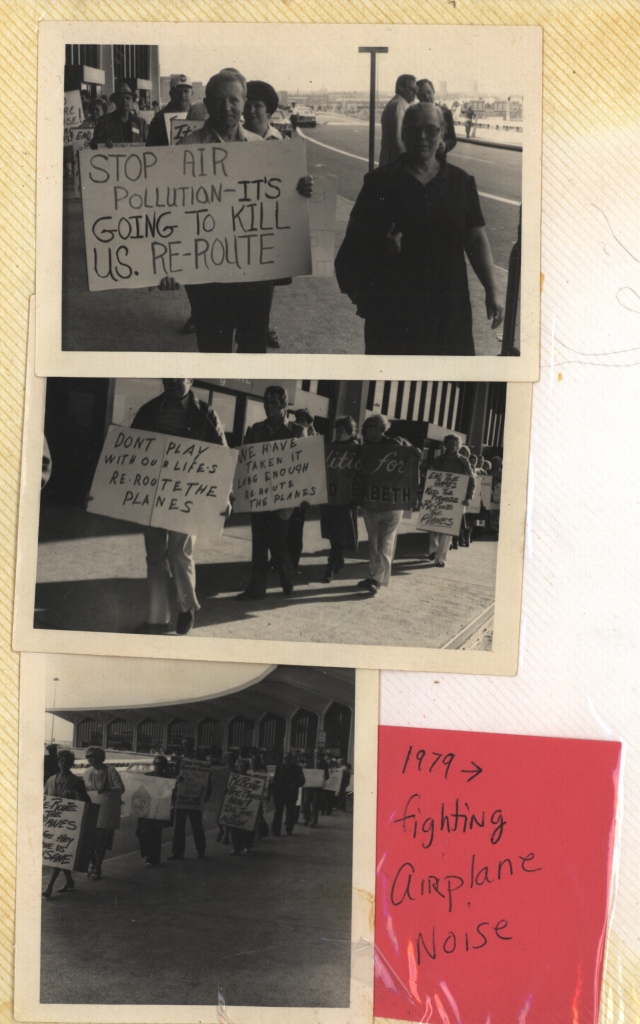

How did this affect children though, they could not drive? Well, active reader, children in the Ironbound are less affected by traffic making them late to school, than through the plentiful, constant noise pollution. The Ironbound is a highly dense environment and this high level of exposure to traffic noise can contribute to varying degrees of cognitive impairment.[21] Various studies have shown that noise pollution undermines performance in school, strongly affecting reading retention, problem solving, motivation, an increase of errors, as well as affecting social and emotional development.[22] “Moreover, there is concern that high and continuous environmental noise may contribute to feelings of helplessness in children”.[23] In a Swiss study, it was found that young children living among high volumes of traffic was correlated with “smaller social networks and diminished social and motor skills”.[24] These affects are demonstrated clearly among schools in the Ironbound. In 2003, only 46% of eighth graders at Oliver Street School scored proficient in math, and 28% at Hawkins Street Elementary School.[25] The two schools are located at opposite ends of the Ironbound. Oliver Street School is only a block away from McCarter Highway, and Hawkins Street School is about a half mile from Route 9, and was surrounded by dozens of car service shops and manufacturing plants.[26]

It is no wonder why the community has pulled together efforts to plead to the council to make changes, such as rerouting air traffic, and redirecting truck routes, but to not prevail. When homes and schools are located near sources of noise pollution, it produces debilitating effects on cognitive development. “It appears that the longer the exposure,” to noise pollution, “the greater the effect.”[27] Schools, daycares, community centers and homes should not be located in areas that damage children’s ability to perform their best, but unfortunately the city of Newark disagrees. [28]

To add to the busy streets, the migration of residents out of Newark caused significant land use shifts from 1950 to 2003. Many houses were abandoned and subsequently demolished, leaving a significant amount of vacant space throughout Newark. This abundance of vacant space magnified many negative elements of living in poorer neighborhoods. These spaces attracted drug dealing, drug use, rats, and became dumping grounds for junk.[29]

Limited Outdoor Recreation for Children

At the same time, the city has failed to provide adequate outdoor space to its residents. In the 1964 master plan, the Division of City Planning reviewed the national standards of recreation space, which recommended 6.25 acres of space per 1,000 people. This would result in “approximately 17 per cent of the city’s total land area being devoted to recreation space”.[30] The local government determined those standard were not applicable to Newark and instead proposed a modified standard of 3 acres of space per 1,000 people. [31] At this point in 1965, Newark was still lacking over 300 acres of recreation and open space, even with the modified standard. In the Master Plan, they also acknowledged the poor distribution of parks, and that they are often too distant and inaccessible to many neighborhoods. Additionally, the density of houses in the neighborhood has left little to no room for yard space, so children flock to the sidewalks and streets, occupying space that was not intentionally reserved for them.

Residents are aware of the issues, as Joseph Della Fave, executive director of the Ironbound Community Corporation said in 2003, ”Open space is a major quality of life issue in the Ironbound. We have half an acre of park space for every 1,000 residents, compared with seven and a half acres of park space for every 1,000 residents in New York and other major cities.”[32] This lack of access to parks and open space has the strongest impact on children. “Limited private indoor space and a lack of proximate safe outdoor spaces has the potential to affect child development through restricting play, exploration, social interaction and independent mobility”.[33]

The ironic part is that the vacant land was seen as a blight to the neighborhood that could only be solved through development, but it had the incredible opportunity to become usable open space. Officials in Newark had the power to decide what happens in that vacant land, and they could create policies to reject new construction, in favor of creating smaller, accessible parks for the public. Especially in the Ironbound, where they are divided from the rest of the city by walking, it is important to acknowledge the limited number of parks the tens of thousands of residents residing there do not have access to.

Newark’s Leaders Fail to Act

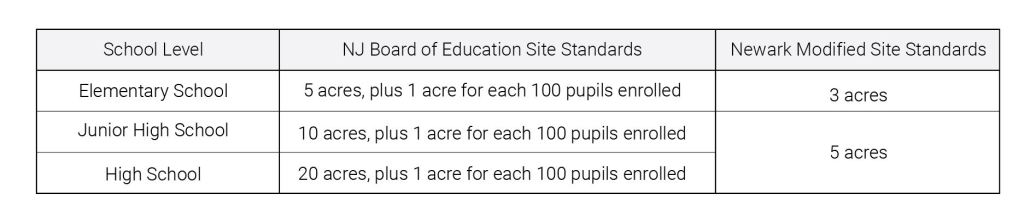

In addition to addressing the general lack of community access to recreational space, it is also important to investigate the space available at schools throughout the Ironbound. Similar to adressing adequate open space, the city of Newark needed to contend with creating modification to the New Jersey State Board of Education site standards for schools, as follows.

Information adapted from 1964 Master Plan

However, just like the realities of open space, Newark had entirely missed the mark to provide children the adequate space their schools needed.

Information adapted from 1964 Master Plan with author’s supplements

To address the severity of the problem, the Master Plan included a section proposing their thoughts about the circumstances. One note they repeatedly mention is how many families will be relocated during their urban renewal programs and highway expansions. “While some of the planned urban renewal programs provide additional space for existing school expansion or new school construction, these programs will require many families to relocate to new areas which could not be determined at this time.”[34] The city officials failed to explain the implications of relocating these families by not answering pertinent questions; Who is moving from what point to where? How many children will this effect? How does this change enrollment in schools? Additionally, they mentioned there are programs to provide space or even build a new school, they do not elaborate on what schools are apart of the program, as well as the many other questions that follow. The final comments regarding school properties passed the responsibility to the Board of Education, claiming that they are planning “future improvements to the school system in Newark.”[35]

By passing the baton, the city officials have made their priorities clear. Resolving the state of the public schools did not make the cut. Without a clear plan or even established goals, there will not be any progress made to rectify the conditions. Since the Master Plan was written, very little had been done in the Ironbound, and there seemingly has only been one elementary school built since 1964.[36] In essence, there was very little done that substantionally addressed the problem of schools in Newark, which were overcrowded and lacked the adequate space the students needed.

Newark Residents Take Action: The Wilson Avenue Bathhouse

When imagining a protest located in the Ironbound district of Newark, NJ, a group of such young children might not be the first thought that comes to mind, yet there they were protesting in the middle of summer.

The call to action that brought them together revolved around the closure of a neighborhood necessity in 1979, the Wilson Avenue Bathhouse. When the site first opened in 1917, it provided the neighborhood with facilities to be able to bathe with hot water and also offered a year-round indoor pool. However, over time, as homes modernized and people no longer needed to travel to get hot water, the facility became a popular swimming destination for locals. Many families enjoyed the facilities, because it gave children a fun place to swim and gave elders a place to get some exercise.[37]

So why did an asset to the community come to the point of closure? Over time, as many well-loved things do, the bathhouse deteriorated, and was never upgraded or maintained properly to keep up with its usage. “This is the fault of the city.” says Joan Pikul, an Ironbound resident who wrote into the Ironbound Community Corporation about her perspective of the problem.

Looking back at the image (see below), it is clear that those who are really suffering at the hands of the city, are the children. From the center poster, laying out the demands of the people, our eyes are drawn to the other posters, reiterating the goal of the protest. By stripping the children of this designated place to play, it forces them up to find other outlets to play, which we can see in the other photos. Although this is solving the problem of the hot summers, they are using hard concrete paved streets, reserved for cars, as a place to play.

What sticks out, in a similar manner to the handmade posters, is the one in the back, attached to the fence, with NO glaring in white letters. It is the only sign in the image that has a dark background with a lighter font on top, reading “Emergency NO Trespassing”. Underneath that is “Field is CLOSED Until Further Notice City of Newark”. This marks the stark division in the picture; the children standing in front, divided by a chain link fence from an unkept field with a large building in the background. This shows the intentional separation the city created between the children and public recreation facilities.

One apparent character that is absent in the image are the parents of the children. Presumably, they are standing behind the camera, calling for the children to look here and smile. The only adult in the photo is a figure behind the children, standing on the other side of the fence. The figure is turned away from the children, possibly conducting field work for the city. Just how he is choosing to look away from the children’s pleas to save the pool, the city choose to look away from the community’s wishes. Subsequently, after the site was closed, it was not properly closed off and attracted crime. According to this flier, handed around in 1984, the city officials had reserved $80,000 to repair the pool, however those funds were never invested in the site.[38] Instead, the city was then interested in selling the property to private developers to build more housing, something the neighborhood was not keen on seeing more of, since there were already two large condominiums.[39]

This photo was one among many, taken between 1979, when the building closed, to the mid 1980s, when the property was finally sold. This event, along with the series of consequences between the 1950s and the early 2000s, documented a period of community heartbreak. From expanding industrialized land, to neglecting to repair the properties of school, the city chose to prioritize making a profit from private developers over providing safe spaces for children and families to enjoy. The repercussions that followed impacted poor child development and even some lives of the children that play around the neighborhood.

Today, residents are still battling the impacts of the industrial plants, and pink fumes were seen omitted in the air early this year.[40] Still, the Ironbound is a gem, and its residents will not give up the battle. Just last year, the city reopened the Ironbound Stadium after being closed for over three decades from the contamination levels in the soil. What was once a site to remind the residents how the city has repeatedly let them down, has now become the site of pride, hosting school games and supporting the community with recreational activities.[41] With the re-birth of the park hopefully what will follow, will be many other opportunities for the city to rectify the damage they planned decades ago.

Endnotes:

[1] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985

[2] U.S. Census Bureau. Social Characteristics in North Ironbound, Newark, NJ, 2018. Prepared by the American Community Survey. (accessed 11/30/2020.)

[3] Stephen M. Wiessner “The Rationale for Preserving Neighborhood Open Space in Newark, New Jersey’s North Ward,” PhD diss., (New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2003)

[4] Stephen M. Wiessner “The Rationale for Preserving Neighborhood Open Space in Newark, New Jersey’s North Ward,” PhD diss., (New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2003)

[5] Kevin Mumford, Newark : A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America, New York University Press, 2007

[6] Stephen M. Wiessner “The Rationale for Preserving Neighborhood Open Space in Newark, New Jersey’s North Ward,” PhD diss., (New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2003)

[7] Zoning is an organizational tool for local governments to determine where and how land is used.

[8] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[9] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[10] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[11] “City Council Votes Against Ironbound,” Ironbound Voices, April 1985, https://digital.npl.org/islandora/object/ironboundvoices%3A16e66d88-3f6a-45cd-b3f0-fdc5c5016e32#page/1/mode/2up.

[12] All information in this paragraph came from; “City Council Votes Against Ironbound,” Ironbound Voices, April 1985, https://digital.npl.org/islandora/object/ironboundvoices%3A16e66d88-3f6a-45cd-b3f0-fdc5c5016e32#page/1/mode/2up.

[13] “City Council Votes Against Ironbound,” Ironbound Voices, April 1985, https://digital.npl.org/islandora/object/ironboundvoices%3A16e66d88-3f6a-45cd-b3f0-fdc5c5016e32#page/1/mode/2up.

[14] “Dioxins and Their Effects on Human Health,” World Health Organization (World Health Organization, October 4, 2016), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health.

[15] “Incinerators: Health Dangers & Problems for Neighbors,” Ironbound Voices, April 1985, https://digital.npl.org/islandora/object/ironboundvoices%3A16e66d88-3f6a-45cd-b3f0-fdc5c5016e32#page/1/mode/2up.

[16] Devna Bose, “’It’s Killing Children and No One Is Talking about It.’ Asthma Taking Toll in Newark.,” NJ (NJ.com, December 21, 2019), https://www.nj.com/essex/2019/12/its-killing-children-and-no-one-is-talking-about-it-asthma-taking-toll-in-newark.html.

[17] Devna Bose, “’It’s Killing Children and No One Is Talking about It.’ Asthma Taking Toll in Newark.,” NJ (NJ.com, December 21, 2019), https://www.nj.com/essex/2019/12/its-killing-children-and-no-one-is-talking-about-it-asthma-taking-toll-in-newark.html.

[18] Devna Bose, “’It’s Killing Children and No One Is Talking about It.’ Asthma Taking Toll in Newark.,” NJ (NJ.com, December 21, 2019), https://www.nj.com/essex/2019/12/its-killing-children-and-no-one-is-talking-about-it-asthma-taking-toll-in-newark.html.

[19] Stephen M. Wiessner “The Rationale for Preserving Neighborhood Open Space in Newark, New Jersey’s North Ward,” PhD diss., (New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2003)

[20] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[21] Hayley Christian, Stephen Ball, Stephen Zubrick, Sally Brinkman, Gavin Turrell, Bryan Boruff, Sarah Foster, “Relationship between the neighborhood built environment and early child development,” Health & Place, 48 (2017), 90-101, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1353829216304646#bbib66 (accessed Nov. 4, 2020).

[22] Lisa Goines, Louis Hagler, “Noise Pollution: A Modern Plague” Southern Medical Journal, Volume 100, Number 3, March 2007, https://docs.wind-watch.org/Goines-Hagler-2007-Noise_pollution__a_modern_plague.pdf (accessed Dec. 1, 2020).

[23] Lisa Goines, Louis Hagler, “Noise Pollution: A Modern Plague” Southern Medical Journal, Volume 100, Number 3, March 2007, https://docs.wind-watch.org/Goines-Hagler-2007-Noise_pollution__a_modern_plague.pdf (accessed Dec. 1, 2020).

[24] Hayley Christian, Stephen Ball, Stephen Zubrick, Sally Brinkman, Gavin Turrell, Bryan Boruff, Sarah Foster, “Relationship between the neighborhood built environment and early child development,” Health & Place, 48 (2017), 90-101, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1353829216304646#bbib66 (accessed Nov. 4, 2020).

[25] Julia Lawlor, “If You’re Thinking of Living In/The Ironbound; A Home Away From Home for Immigrants,” The New York Times (The New York Times, January 11, 2004), https://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/11/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-living-ironbound-home-away-home-for-immigrants.html.

[26] Google Maps. 2020.

[27] Lisa Goines, Louis Hagler, “Noise Pollution: A Modern Plague” Southern Medical Journal, Volume 100, Number 3, March 2007, https://docs.wind-watch.org/Goines-Hagler-2007-Noise_pollution__a_modern_plague.pdf (accessed Dec. 1, 2020).

[28] Ironbound Community Health Project, Report from the Ironbound Health Project About the Fight Against Airplane Noise. Letter, sent on March 25, 1980. (accessed on Nov. 22, 2020). https://digital.npl.org/islandora/object/ironbound%3Ab272be00-f2ac-4c5e-8e33-5871688614bc#page/1/mode/1up

[29] Stephen M. Wiessner “The Rationale for Preserving Neighborhood Open Space in Newark, New Jersey’s North Ward,” PhD diss., (New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2003)

[30] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[31] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[32] Julia Lawlor, “If You’re Thinking of Living In/The Ironbound; A Home Away From Home for Immigrants,” The New York Times (The New York Times, January 11, 2004), https://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/11/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-living-ironbound-home-away-home-for-immigrants.html.

[33] Hayley Christian, Stephen Ball, Stephen Zubrick, Sally Brinkman, Gavin Turrell, Bryan Boruff, Sarah Foster, “Relationship between the neighborhood built environment and early child development,” Health & Place, 48 (2017), 90-101, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1353829216304646#bbib66 (accessed Nov. 4, 2020).

[34] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[35] City of Newark, New Jersey & Central Planning Board & Department of Administration, Master Plan 1964 City of Newark NJ, Prepared by Division of City Planning and Candueb, Fleissig, Adley & Associates for the Newark Central Planning Board: Newark, 1965.

[36] East Ward Elementary school was built in 2019.

[37] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985

[38] Ironbound Community Corporation, flier, When Can We Swim in Wilson Ave. Pool?, 1984

[39] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985

[40] Eric Kiefer, “The Color Purple: Newark Residents Fed Up With Incinerator Smoke,” Newark, NJ Patch, May 1, 2020. (accessed on Dec. 15, 2020). https://patch.com/new-jersey/newarknj/color-purple-newark-residents-fed-incinerator-smoke.

[41] Barry Carter “After 32 Years, N.J. High School Gets to Play Football and Soccer Again,” NJ, October 13, 2019, https://www.nj.com/essex/2019/10/after-32-years-nj-high-school-gets-to-play-football-and-soccer-again.html.

Primary Sources:

Master Plan 1964 City of Newark: http://archives.njit.edu/archlib/digital-projects/2000s/2009/plans/njit-naa-2009-0004-p.pdf

This primary source will help aid my research because it will provide me the specific data that I need to prove evidence about how the design of the Ironbound district consequently impacts the development of children through limited access to park, but especially due to the amount of nearby industrial zones.

The main objectives of the city plan were revolved around the industrial economy activity and improving transportation infrastructure, described clearly on page 34 “to stimulate industrial growth through the clearance and redevelopment of obsolete areas, the rehabilitation of marginal industrial areas including provision of loading and parking space, and the elimination of nonindustrial uses from industrial areas where possible, and the provision of industrial land for new industries or for the expansion of existing industries”. While one sentences of the entire objective reading “ Particular emphasis was given to changing neighborhood patterns and their needs for certain community facilities.” Based on the historical context of the time period, Newark was experiencing a decline in their population, due to people migrating to the suburbs, in addition to the migration of industrial companies moving out of urbanized areas to more rural and suburban ones. It is clear how important their goals aligned with keeping people working int the city. With this in mind it understandable why Newark, a city home to an international airport, major ports and extensive railroads, naturally places greater emphasis on the arguably most important sector of its economy. But at what cost? Newark does not have enough land for schools to have the proper amount of green facility space, nor does it supply the right amount parks for the amount of people living in the city. On page 69, the site adequacy for schools is described as “most of Newark’s school sites are significantly below recommended state standards. Ninety per cent of all elementary school sites are less than two acres in size and junior and senior high school sites are also relatively small, ranging from one to five acres.” With regards to the amount of park space and play space, the national standard at this time recommends 6.25 acres per every 1,000 residents, and Newark has determined that they cannot be applied to the city. “The use of a 6.25 acres per 1,000 population would result in approximately 17 per cent of the city’s total land area being devoted to recreation space.” So they have adjusted that number to be 3 acres for every 1,000 residents, half the recommended amount. The plan continues to point out “The most significant deficiency of recreational space exists in the provision of playgrounds and playfields in conjunction with the Newark public schools. Most of the existing schools occupy sites which are much smaller than the minimum standards generally accepted by state school planning authorities.” This shows that Newark has placed greater emphasis on strengthening and further developing the already large industrial sector of the city, instead of providing the residents, and particularly children, with the proper amount of green space. They have made their priorities clear through the master plans.

Newark Master Plan (1978): http://archives.njit.edu/archlib/digital-projects/2000s/2009/plans/njit-naa-2009-0005-p.pdf

This primary source will help aid my research because it will provide me the specific data that I need to prove evidence about how the design of the Ironbound district consequently impacts the development of children through limited access to park, but especially due to the amount of nearby industrial zones.

Secondary Sources:

Kevin Mumford, Newark : A History of Race, Rights, and Riots in America, New York University Press, 2007 This online book tells the history of Newark, NJ in the 20th century, and I am particularly interested in the first part of the book about the formation and roots of the city.

This source will help me have a better understanding of how the city formed, and what were specific moments in time that act as evidence in my arguments. I am still formulating the time period(s) I am focusing on, so I am hopeful this book will give insight to determine critical moments. Also, I think that having a reference for the history of the city will help to better establish the ground work for the essay.

Relationship between the neighborhood built environment and early child development, 2017. This online journal analyzes the immediate surrounding influence of where a child grows up to its development.

This source will be very helpful for me when formulating the connection between zoning realities and child development. The journal examines areas from yard space, access to parks, exposure to pollutants, proximity of school and shops and the quality of the built infrastructure. Although the analysis was in Australia, there are significant observations about the socio-economic factors that can be observed similarly in Newark.

Image Analysis:

Photos from the Fight to Save Wilson Ave. Bathhouse. For analysis below, focus on image above with children standing in front of fence.

When looking at the image above, taken in 1980, one’s attention is first drawn to the sign in the middle that says, “We want a safe clean place to play!” The sign is written in dark letters on a bright white background, with faint smiling stars surrounding the words. It is being held up by two young children, both in bright white tops, one even showcasing Minnie Mouse, and standing among a small crowd of similarly aged children. When imagining a protest located in the Ironbound district of Newark, NJ, a group of such young children might not be the first thought that comes to mind, yet there they were protesting in the middle of summer.

The call to action that brought them together revolved around the closure of a neighborhood necessity in 1979, the Wilson Avenue Bathhouse. When the site first opened in 1917, it provided the neighborhood with facilities to be able to bathe with hot water and also offered a year-round indoor pool. Having a public bathing facility with hot water gave many people in the neighborhood who had lived in homes without hot water the ability to bathe comfortably, and it was widely used. However over time, as homes modernized and people no longer needed to travel to get hot water, the facility became a popular swimming destination for locals. Many families enjoyed the facilities, because it gave children a fun place to swim and get elders a place to get out for some exercise.[1]

So why did an asset to the community come to the point of closure? Over time, as many well-loved things do, the bathhouse deteriorated, and was never upgraded or maintained properly to keep up with its usage. “This is the fault of the city.” says Joan Pikul, an ironbound resident who wrote into the Ironbound Community Corporation about her perspective of the problem.[2] After the building was closed in 1979, it cut the community, specifically children from access to a fun place to play.

Looking back at the image, it is clear that those who are really suffering at the hands of the city choosing to close the bathhouse instead of fixing it up are the children. From the center poster, clearly laying out the demands of the people, our eyes are drawn to the two posters flanking the center one. The right poster, reiterating the goal of the protest “We want our pool”, but the left pulls the viewer out into a greater perspective “We are the future”. By stripping the children of this designated place to play, sets up them to find other outlets of play, which we can see in the other photos, of the children playing in the streets with sprinklers. Although this is solving the problem of the hot summers, they are using hard concrete paved streets which are reserved for cars as a place to play.

From the posters, written all on bright white backgrounds, one’s eyes are carried to the crowd of children holding them, a mix of boys and girls, aged from possibly eleven to six, all smiling and most having colored skin. What sticks out, in a similar manner to the handmade posters, is the one in the back, attached to the fence, with NO glaring in white letters. It is the only sign in the image that has a dark background with a lighter font on top, reading “Emergency NO Trespassing”. Underneath that in dark letters on a light background is “Field is CLOSED until further notice City of Newark”. This marks the stark division in the picture; the children standing in front, divided by a chain link fence from an unkept field with a large building in the background. This shows the intentional separation the city created between the children and public recreation facilities. There is one other prominent poster, located just in front and to the right of the city’s sign, being held up by a few young girls saying “Take time to stop and smell the toxic waste.”

One apparent character that is absent in the image are the parents of the children. Presumably, they are the photographers in this instance, standing behind the camera, calling for the children to look here and smile. This is symbolic of who is affected the most by the closure of the bathhouse, and without seeing the parents beside the children, it exposes the city to confront the weight of their neglect. The only adult in the photo is a figure behind the children, standing on the other side of the fence. The figure is turned away from the children, possibly conducting field work. This shows the separation of adults and children in this fight to reopen the pool, and how he is choosing to look away from the children’s pleas to save the pool. He is ignoring them just the same way the city ignored the community’s wishes. Subsequently after the site was closed, it was not properly closed off and became a desirable place for property destruction and vandalization. Not only did the city take away a community resource, but they formed a site in the city that was unsafe and attracted crime. According to this flier, handed around in 1984, the city officials had reserved $80,000 to repair the pool, however those funds were never invested in the site.[3] Instead, the city was then interested in selling the property to private developers to build more housing, something the neighborhood was not keen on seeing more of, since there were already two large condominiums.[4]

This photo was one among many, taken between 1979, when the building closed, to the mid 1980s, when the property was finally sold, to document this period of community heartbreak. The city chose to prioritize making a profit from private developers over saving a valuable safe space for children and families to enjoy.

___________________________________________________________________________

[1] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985.

[2] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985.

[3] Ironbound Community Corporation, flier, When Can We Swim in Wilson Ave. Pool?, 1984

[4] Joan E. Pikul, letter to the Editor, ‘Bathhouse’ Issue Clarified, Newark, October 14, 1985.