‘We’d Like to Forget, the World won’t let Us’: A Disastrous Event is Now Remembered for the Positive Outcome

by Isabella Sangaline

Site Description:

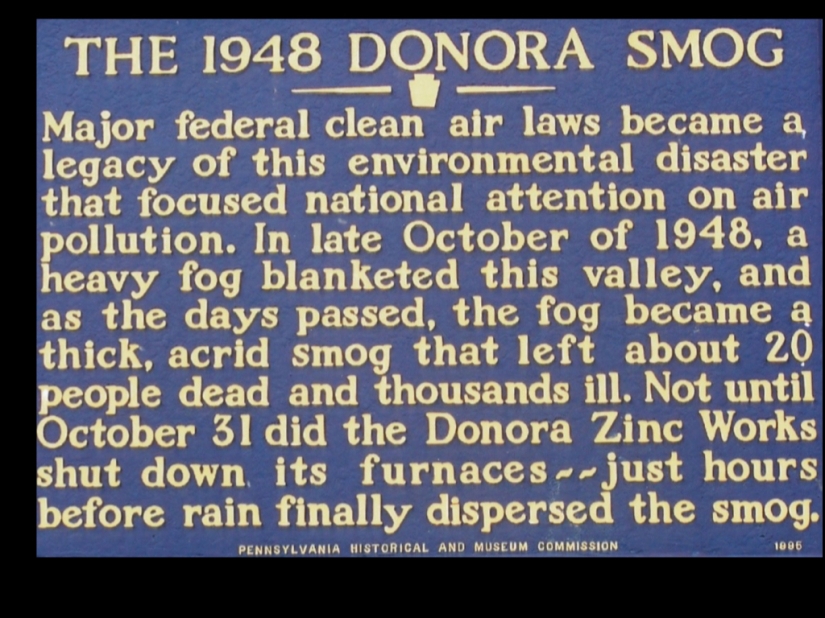

Donora is a small industrial town located on the Monongahela River, south of Pittsburgh, that sat between two factories. In October 1948, a weather anomaly caused the smog that sat above the town to descend into the town from October 26 – 30/31 resulting in death and long-term health affects. During a lawsuit, the corporation defended itself stating that this was an act of God, refusing to take responsibility. Afterwards, residents of the town preferred to not talk about the incident – it was regarded as a dark moment in their history. Now Donora has a historical marker and Smog Museum. So how did the community’s memory and relation of the event change over time? And how does racial and class inequality impact this relationship? I look at the long-term social impact, understanding why the town did not talk of the event until recently. Corporations using act of God defense and smog descending into towns are still problems faced today and understanding this event can help understand the inequalities and legacies that drive these issues.

Final Report:

Driving through Donora today, it seems like most other small steel towns in Pennsylvania. As you drive through the town, you can see the Monongahela river flowing past, with bridges occasionally extending across it, and the green cliffs on the other side. You may not guess the importance of this town to environmental history in the United States. Along the river sit the remnants of the old steel and zinc works that once operated in Donora. On McKean Ave., you drive by a small building with a large orange and black sign stating, “DONORA SMOG MUSEUM: CLEAN AIR STARTED HERE.”

This sign and museum reference back to October of 1948 when a weather phenomenon caused the smog from the local steel wire and zinc works to descend into the town for four to five days, causing one of the worst air pollution disasters in the United States. On the morning of October 26, 1948, Donora was covered in a blanket of thick smog. This was not unusual for this town. Foggy mornings would often clear up by noon, but this morning was unusual. The fog did not clear up; in fact, the fog only grew thicker.[1] The episode was caused by a weather inversion preventing the hot air from rising out of the valley, trapping the smog coming out of the mills. It became so dark in the town that lights had to be kept on during the day and people walking outside struggled to see what was right in front of them. During this time, residents of Donora experienced various levels of respiratory problems from breathing in the cocktail of pollutants. About twenty people died during the event or shortly after from breathing in the smog.

This disaster helped propel conversations in the United States around air pollution. During the year after the episode, a study was conducted to understand causes and effects of the smog descending into the town. The study provided quantitative data on air pollution and its effects on humans and the environment, producing a report in 1949 presenting the results.[2] This event is a primary example of the dangers of air pollution and it made an impact. It propelled environmental conversations locally, nationally, and globally as people began to realize the dangers of smog and air pollution. Prior to this disaster, there was limited knowledge about the effects of smog and long-term exposure of air pollution – this propelled that change.[3] In 1963, the Clean Air Act was passed. Even today inversions are considered when discussion air pollution regulations. Therefore the smog museum now claims that clean air began in Donora.

Everyone living in Donora experienced the smog, however socio-economic inequalities influenced who was affected by the smog along with their responses and memories of it. The American Steel and Wire Company created and enforced local inequalities with the city, specifically creating a class and ethnic divide within the town. Everyone in the town was connected to the mills directly or indirectly and this affected their thoughts on the presence of the mills. Those who tended to work directly for the mills relied on it for economic support, so they were hesitant to speak out against the mills. They dismissed the warning signs that the pollution was harming the community and children growing up in Donora dismissed it as “just the way things were.”[4] Residents who had crops or livestock did not enjoy having the mills around as it killed all the plants and animals. Some people in Webster and Donora were already engaged in legal disputes over damages from pollution with the American Steel and Wire Company prior to the disaster.[5]

To make my argument, I draw on methods common to environmental and social history. I combine these ways of looking at history to understand the social factors of this disaster and how the residents remember the event. I engage with various types of sources, such as oral interviews and government health studies, to understand what happened in Donora during this time. There are voices present from multiple groups of persons, yet my intention is to prioritize the voices of the residents of Donora. This is required to conduct social history. Even with this priority, there is a reliance on scientific, quantitative data to understand broader experiences and affects from the pollution. The formal government and scientific documents present the broader information on the event and are used to support the more intimate sources describing specific experiences from the residents.

Life Before the Smog Episode: Differing Experiences of a Changing Environment

Prior to the 1948 smog episode, how residents were connected to the mills affected how they viewed the presence of the mills in the town. A large portion of the population worked for the American Steel and Wire Company to some capacity. Managers, foremen, laborers, and nurses were hired to work for the company. The managers and foremen often lived in cement city, housing provided and maintained by the company. Most laborers did not have this privilege and often had to build their own homes after their shift in the mills. Everyone in the town had to deal with the environmental conditions created by the mills. Each group had their own experience and feelings about the mills in the town. Those who worked for US Steel and Wire either ignored the dangerous conditions or were oblivious to the conditions because the mills provided economic support for the workers. Those who directly relied on agriculture were openly displeased by the pollution coming from the mills.

Conflicting interests in the town generated positive and negative attitudes towards the mills. Prior to the smog episode, a majority of those living in Donora had a positive relationship with the mills. The town was comprised, largely, of immigrants in the 1940s and was viewed as a growing and prospering industrial town to the residents.[6] This supposed prosperity was credited to the mills in the town. U.S. Steel and Wire Company was the largest employer within Donora and over half of the employed residents worked for the company.[7] The mills became a symbol for money and growth for the town.[8] This was not an uncommon trend for steel towns or towns that faced pollution from industrialization.[9] Not everyone saw the mills as a positive addition to the town. Crops, orchards, and livestock were dying, hurting the people who relied on them to support themselves. U.S. Steel and Wire Company paid off its first official complaint on the issue in the 1920s – about twenty years before the smog disaster.[10] There was a supposed conflict surrounding the mills based on how the residents related to them. The mills provided economic support for many, however, it hurt those that directly relied on agriculture.

Those who labored in the mills overlooked the dangerous conditions because they relied on the mills for a job to support their families. The workers in the mills knew that the work they were doing was dangerous, but disregarded it because it supplied the “bread and butter” for their families.[11] These men had to avoid the areas where carbon monoxide built up to avoid suffocation. An interviewee recalled an open area in the mills where there was a buildup of carbon monoxide. He mentioned that it was common to see dead birds that flew into the area and suffocated to death. When the workers would spend too much time in heavily polluted environments, they would come down with a case of the “zinc works jitters.” The workers prioritized economic stability over their own safety, a trend that is also present during and after the smog episode.

Nurses who worked for the mills and treated the workers were suspicious of their working conditions. Many workers that they saw suffered from respiratory problems and the zinc works jitters, likely brought on from beathing the chemicals in the air from the zinc and steel making processes. The symptoms included light-headedness, dizziness, and difficulty breathing.[12] The nurses were concerned for the safety of the workers and would sometimes encourage them to leave their shifts early because of the health concerns, but the workers often dismissed the concerns and returned to work. Even though the nurses were employed by the same company, they were skeptical of the working environment of those in the mills.

Even though these groups all worked for American Steel and Wire Company, there were class and ethnic divides that became evident through their housing. The cement homes built in Donora were supposed to be low-cost, decent housing for the workers. Once the houses were complete, they were primarily occupied by the factory’s foreman or middle management.[13] The majority of the people in the town were of Slavic descent, with smaller Spanish and Black populations within the town.[14] Unlike the rest of the town, the majority of those in cement city were Scots or Scot-Irish. The company even maintained the houses in cement city.[15] In a later interview, one resident of Donora stated that it was not uncommon for those who worked in the mills to leave their shift to build their own homes and other buildings in the town. Those with higher status within the mills had a higher quality home and did not have to pay to maintain it.

Even those who did not work directly in the mills were likely still connected to it, as many children in Donora had family who worked in the mills and they had to live with the environmental conditions. Many children simply accepted it as “the way it is.” Pollution was not discussed prior to the smog episode as pollution was not part of their dialogue. As one interviewee mentioned, pollution was not something they knew of or spoke of prior to the episode. Children would just skip over the cracks in the ground and did not ask what caused the lack of vegetation in the town. [16] They adapted to the environment and found ways to have fun unaware that these were signs of a degrading environment.

Those who relied on agriculture for their livelihood saw the mills as a negative addition to the town, as the environmental conditions brought on by the mills hurt the vegetation growing in and around the town. Once the factory had been around for a few years, there was a noticeable change to the environment. Crops, orchards, livestock, and grass in Donora died. There was no vegetation and the smell of sulfur hung in the air. [17] The lack of plants stabilizing the topsoil made it so that it would often get stripped away. Fences and houses near the mills faced damages caused by the pollution. U.S. Steel and Wire would maintain the cement homes. People who lived outside cement city had to maintain the property on their own, with no reimbursement for the damages. Those living far enough away from the mills, where vegetation could grow, noticed an obvious wilting of the plants when the wind would push the smog in their direction. The American Steel and Wire Company just dismissed this claim.[18]

These differing connections to the mills created various opinions about the presence of the mills and reinforced class and ethnic inequalities within the town. The workers in the mills chose to endure dangerous working conditions for economic support, and even those who were suspicious did not speak out during the time. Not all workers were treated equally within the mills. Foremen and managers had access to higher quality housing than the standard laborers. For children, they accepted things as they were, not questioning the cause of the environmental issues. Those in agriculture tried hold the mills accountable since at least the 1920s. These inequalities and relationships with the mills would be important in determining how potentially severe the smog may affect someone.

The Episode: Same Experience, Differing Responses

Inequalities in the town, such as age and health, housing, and access to healthcare, along with the differing relations to the mills influenced how severely the smog affected someone and their response. The smog did not affect everyone equally, despite everyone in town experiencing it. In 1949 the results of a study conducted in the year following the event presented the findings on the effects and causes of the smog disaster.[19] Factors such as age and health status, housing conditions, and access to healthcare were factors that were relevant in determining how severely one was affected by the smog. Older residents and residents already suffering from respiratory issues were the most severely affected by the smog. Higher quality houses were able to better keep the smog out of the house, while those in lower quality homes had to improvise ways to keep the smog out. During the episode, hospitals filled up and people found their own ways to relieve themselves from the smog. When the smog first descended, it was not taken seriously by much of the town, as it seemed like a normal foggy morning. It was not taken seriously until people in the town started becoming ill from the smog. During this time, the town came together to support each other, but who was to blame for the smog was a controversial issue.

Age and health were two physical conditions that greatly influenced how severely someone was affected by the smog. Generally, as the age of a person increased, so did how severely the smog effected them. Over half of the population consisting of persons ages thirty-five to thirty-nine and above reported affection from the smog.[20] Persons who were already inflicted with a cardiovascular disease also reported higher rates of affection from smog. Previous health status would be an issue in legal battles to come because those representing the deceased would have to prove that there was no previous health condition to justify death from the smog episode, such as with Susan Gnora.[21] Autopsies and X-rays of those who died during the episode and of those severely affected had visible damage done to their lungs by the smog. X-rays of lungs showed that the lungs were becoming inflamed and irritated from all the dust and smog entering the system.[22]

The quality of someone’s house was relevant in the severity of affection, as higher quality homes were able to keep out more smog than the lower quality homes. The 1949 report broke the population into residential districts. The report notes that housing was an important factor for determining how severely one may have been affected by the smog.[23] Residential areas that had higher amounts of affection also had the least amount of satisfactory housing. While there is no chart to display this data, the report states that as the number of dwellings rated as satisfactory and above increase, the percentage of reports decreases.[24] Those who lived in homes that could not keep out the smog experienced dust building up on surfaces that were near windows or cracks. One mother recalled noticing dust covering a stovetop that was cleaned earlier the day when she entered the kitchen to get food for her child.[25] Once people in the town realized that the smog was harmful, they began to board up their houses or stuff rags into the cracks to keep out the smog.[26] While many residents took up their own defenses against the smog, others called local doctors or went to the hospital. While the report does suggest further research into housing conditions, it does not suggest improving housing as a way to prevent such an incident in the future. The report indicating that housing was an important factor in determining severity of affection shows that one’s socio-economic status was important in understanding how the smog affected someone.

During the episode, not everyone in Donora had equal access to healthcare. There were multiple causes as to why one may not have had access to care during the incidenr. First, there was the issue of hospitals filling up. As more people were affected by the smog, hospitalizations increased. This increase impacted the hospital staff’s ability to care for patients, as those working there were not able to treat or see each person who came in for a visit. Doctors did make house calls during this time, but they were limited in what they could do. One doctor simply advised his patients to leave the town.[27] Gnora was able to see a doctor but did not leave town. Her symptoms started off as not severe, her family notes that they did not expect her to die. Yet the symptoms quickly increased, and she died on October 30, 1948.[28] To help relieve the overwhelmed doctors, fire fighters began delivering oxygen to people’s homes. Other people simply refused to see a doctor or relied on themselves to get them through the smog episode.[29] The smog did not affect everyone equally, so in turn, not everyone had the same reactions to the smog or required the same care.

The differing connections to the mills and differing levels of affection by the smog caused the residents of Donora to have a range of reactions to the smog episode. These responses were heavily influenced by the inequalities highlighted during the episode. A major factor in understanding the responses to the event is looking at how people related to the mills. The residents had a complicated relationship with the mills. Much of the town depended on the mills for economic stability, but others were disturbed by the environmental affects the pollution had on the town. Those who relied on the mills tended to deny its role in the disaster. Those who were hurt by the mills were quick to blame it for its role in the disaster.

Figure 5: This image shows local emergency crews delivering a shot of oxygen to a Donora resident

As more people became ill, the residents began seeing the smog as something dangerous that had infected the town. No one realized that this fog would have negative consequences until they were already becoming ill, mostly with respiratory problems, and they were struggling to breathe. As doctors and nurses became busier with cases of people affected by the smog, local fire fighters had to begin acting as emergency crews delivering “shots” of oxygen to people in the town.[32] Since they did not have enough oxygen shots for everyone, those who could receive the shots, received a few seconds of breathing clean air. These were not medical experts delivering the clean air, just members of the community trying to support each other. Figure 5 above depicts three firefighters acting as an emergency crew helping a man receive clean air from the oxygen tanks while the man’s family stands around the couch watching the process.[33] While the men being fire fighters is not evident in the photo, once added to the context from the event, the photo has more to tell.

Figure 5 shows a moment when the smog was being taken seriously by the residents in Donora. While the photo may not be able to reveal much information on its own, when the photo is cross-referenced with other material, it is a useful visual reference for understanding the event. The focal point of the photo is an older gentleman laying on a couch with an emergency crew member holding an oxygen mask to the gentleman’s face. With the older man as the center, surrounded by his family, acts as a visual representation of one of the groups most affected by the smog. This information is then backed by the 1949 report. In the photograph, we know it is an emergency crew helping the man because the caption has described the scene as such. It can also be deduced that the men are not medical professionals, based on the lack of uniforms; but they do have some medical or technical knowledge to be able to work the machine. As stated in interviews and other photos, these emergency crews were comprised of local firemen. The old man had to be treated in his home, assumably a cement home based on what is seen in the photograph, which says there was an issue with access to healthcare. While the reason to accessibility is not evident in the photograph, other sources confirm that there was an issue of accessibility as hospitals were filling up with patients. On its own, the photo may seem vague, especially since it was a staged photo, yet it acts as a representation of how the town was taking the smog seriously and the inequalities involved during the disaster.[34]

There were conflicting emotions, linked to the relationship with the mills, floating around the residents in Donora as the town had experienced a traumatic event evoking sadness, anger, and fear. Those who lost someone during the event, would have been mourning their loss immediately after the event. This sadness also mixed with anger, as several residents in the town blamed the American Steel and Wire Company for allowing such an event to occur. Some people filed lawsuits against the mills, but the company never accepted responsibility.[35] This continued to frustrate those living in the town. People were angry at U.S. Steel and Wire while others feared the company.[36] Many people in the town declared their loyalty to the mills and denied that the pollution was the cause of the smog. This loyalty was a mix of economic dependence and fear of the company. People continued to work in the mills after the episode; it did not stop them from earning for their families. These conflicting emotions were especially highlighted when the doctors, scientists, and nurses working on the 1949 report tried to work with the residents of the town. When collecting data, the scientists often ran into patients downplaying their symptoms because they were afraid of being reprimanded by the American Steel and Wire Company or the patients would exaggerate their symptoms because they were so angry and upset by what the mill had done.[37]

Shifting Memory: Lingering Consequences from the Smog

Just as people had different responses to the smog episode, how they remember it differs and has changed over time as their relationship with the mills continued to change. How the people in Donora experienced to the event directly relates to their memory of the severity of the event. As discussed previously there were mixed reactions and responses to the event that were heavily influenced by how severely the smog affected them and their relationship to the mills. When thinking of the event, each person was affected differently. Some lost loved ones, some still resent the mills for the damages, some think of the positives that came from the episode, and others have moved on. Many people in Donora felt as though the whole nation had its eye on them. When people thought of Donora, the first association they had was the smog disaster. This negative association upset the residents living in Donora. Many survivors tried to forget and move on from the disaster. It was not until fifty years after the event was the smog disaster discussed as something positive.

After the disaster, most residents wanted to forget and move on from the episode, but felt as though the world would not let them. North Carolina welcomed the residents to relax and escape the smog. An article about the disaster printed in the Times even made its way to Germany, where poet Günter Kunert read about it. He wrote a poem about the episode that would be published in 1950. [38] Newspapers across the United States reported on the events of the smog episode as they unfolded. Eager readers waited to see the results of the study conducted the year after.[39] Despite the additional attention, many of the laborers in the mills returned to work as normal, as if nothing had happened. Many workers were scared about the company firing them for speaking out against the pollution and scared that the mills would shut down if environmental regulations were enacted. In 1967, the mayor of Donora gave a radio interview where he said, “We don’t like to talk about the smog here in Donora, we think it’s an unpleasant episode. We’re reconstructing the community and we’re doing pretty well now and look for a good future. So the smog episode, very frankly, we’d like to forget, but the world won’t let us.” [40] In 2007, councilman Don Pavelko commented on the survivor’s lack of discussing the event, stating, ““It was sort of a black eye to Donora. I always heard, ‘Let it die, let it die.’”[41]

After the episode, additional events such as American Steel and Wire Company refusing responsibility, the mills shutting down, and ongoing respiratory illness in the town, continued to generate more negative feelings about the smog. Some residents wanted justice for the damages caused by the smog episode and sued American Steel and Wire Company. Throughout the lawsuits, American Steel and Wire Company denied responsibility for the event, claiming it was an Act of God. In their defense they claimed that the disaster was primarily the cause of the terrain and weather phenomenon.[42] These cases ended up being settled for a fraction of what was being sued for.[43] The mills leaving the town is another moment that causes resentment, distrust, and negativity when remembering the 1948 smog disaster. During the episode, people in the town continued to remain loyal to the mills, but when the mills left, they felt betrayed and angry. The entire community was hurt when the mills left, and some people blamed the regulations and bad publicity from the smog episode for this. People who did not find a new line of work now had to travel for employment. Their families rarely followed, so one person would leave and send back money. Negative feelings and suspicions about the event manifested into quietly blaming the pollution from the mills for respiratory-related deaths in the town. Many people in the Donora-Webster area now credit the air pollution from the mills to premature deaths and higher rates of respiratory issues.

The 1949 report, while priority was given to quantitative data that recorded physical conditions of the residents and environment, its refusal to assign blame to the mills’ pollution allowed American Steel and Wire Company to deny responsibility.[44] Those who wrote the report, government hired scientists, pulled away from directly pointing any fingers at the steel and zinc works in Donora and described Donora as being economically dependent on the mills, as the following is highlighted on page two: “Donora’s industrial life is dominated by a steel and wire plant, and a zinc plant.” The report makes an effort to highlight the industrial traffic, such as trains, boats, and cars, that constantly made its way through the town as adding to the pollution. Boats ran up and down the river, trains rolled in and out of town, and cars drove through the streets. While these are sources of pollution for the town of Donora, it continues to act as a decentering of the pollution put out by the mills. This report was produced when there was a trend to diminish the human, social, and economic factors that influenced who is affected by disasters and when governments are looking for scientific and technological explanations in hopes of being able to monitor and control nature.[45] By decentering the mills, it becomes easier for the mills to deny responsibility for the event.[46]

As discussions about the smog continued to occur between survivors and those born after the smog disaster, people began to celebrate the positive consequences of the event. For nearly sixty years after the episode, residents were hesitant to discuss it. On local news station WPXI in 1998 a report mentioned how the people in the town are hesitant to discuss the episode. The report discussed the town’s plans to honor the fiftieth anniversary of the event by holding a funeral for those who died and reflect on the positive changes as well as featured a local high student discussing the event. He noted that the episode is hardly discussed in Donora. Thanks to the efforts of people like the high school student, the local historical society, and other people in Donora, the community now sees the event in a more positive light. Part of this transition in memory can be credited to the shifting generations in the town. As time goes on, there are fewer living persons who remember the events of the 1948 smog episode. When listening to the interviews of Rumor of Blue Sky, it is not hard to miss the survivors dealing with the conflicting emotions that are brought up when discussing the episode. There are hints of remorse as they realize they normalized a polluted environment, and they are visibly happy when they discuss the ways the town has grown since the mills leaving. The hillsides are green again and one can now grow a garden in the town without plants wilting or dying from pollution. They are proud of the ways that the community was able to come together to support each other during the episode and of the reform that has come from the smog.

Now the town aims to celebrate the good things that have come from Donora and use the event as a gateway for visitors to learn about other aspects of Donora’s history. Just like the people who hold them, memories are shifting and fragile. As people grow and reflect on a particular event, such as the Donora smog disaster, their new experiences and ideas will influence how they relate to that event. As the discourse around the episode shifted away from the negative impacts, so did the memory of the event. The smog episode helped fuel conversations around air pollution that eventually lead to the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1963. There is a historical marker in the town informing people who walk past it of what occurred here. The Smog Museum proudly displays, “CLEAN AIR STARTED HERE!” This museum is not only about the smog disaster. It uses the notoriety of the smog episode to draw people in, yet it covers a whole range of subjects, themes, and time periods involving Donora’s history. A visitor may be brought in by the smog but can leave also learning about cement city or major league baseball players from Donora. In 2018, a local brewery in Charleroi even made an imperial stout named “Donora Smog” after the event and to honor their Donora roots.[47]

Conclusion

Driving through Donora today, Donora is surrounded by green cliffsides and the sky is clear. Since the closure of the mills and the enactment of regulations on pollution, the vegetation in Donora has grown back. The only signs that Donora is different from the other steel towns in the area is the presence of the Smog Museum. Here, the community has honored the event with a way to educate visitors on the legacy of what was thought of as a dark moment in the town’s history. Such a visible recognition of the smog episode represents the shifting attitudes about the event and drive to control the narrative. The community went from seeing the episode as a negative part of the town history to seeing it as a positive: “Clean air started here!”[48]

Socio-economic inequalities in Donora were a factor in determining how one was affected by the smog and their memory of the event. Different groups of people had different connections to the event. Those who depended on the mills for economic stability saw the mills and smog as a symbol of economic prosperity, but those whose farms were killed by the pollution saw the mills as a nuisance. Once the smog episode hit, the already complicated views of the mills became more complicated. Some people blamed the mills and wanted justice. Others simply wanted to forget the event and move on as if nothing happened. Even with these complexities in understanding the event, the residents had a largely negative connotation of the event. They did not want to discuss it and were exhausted by the attention the town received from the event. It was not until nearly fifty years after the event did survivors start discussing the event in a more positive tone. Now the residents, although much of the town has not directly experienced the event, honor the event for the positive outcomes and use it to introduce visitors to other aspects of Donora’s history.

What occurred in Donora was not an isolated event and its legacy is still seen around the world. Inversions trapping smog had previously occurred in Belgium in 1930 and then in London in 1952.[49] After what happened in Belgium, there was already some attention on the issue of smog and air pollution. It was not until after the disasters from air pollution that people began to take smog and air pollution more seriously. In Clairton, a town twenty to thirty minutes down river from Donora, some residents of this town engaged in a legal dispute with US Steel over damages from the pollution because the local coke works were not following the emissions guidelines. There has not been an inversion in Clairton, but there is potential for one to happen. Even though it is a rare weather phenomenon, it is still taken into consideration when discussing air pollution regulations.[50] The memory of this disaster lingers in current air pollution discussions. What happened in Donora is tragic, but it was a key moment in exposing people to the dangers of air pollution.

The town of Donora had a complicated relationship with the steel and zinc works that is highlighted through their memory of the event. Their memory shows that the mills were viewed as important to the town as it was a source of income and financial stability in the town. The mills also enforced class and ethnic divides, even amongst its own workers. In public discourses, this economic dependence is constantly highlighted. What is ignored was how there were people against the mills and suspicious of the pollution since the 1920s. All the negative press led to fear about how the mills would respond, and the residents of the town avoided discussions about the smog. Today we now see the new generations of Donora residents and the survivors of the original disaster coping with the history of their town as they celebrate the positive outcomes from this event. Clean air started in Donora.

[1] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[2] The year-long study was conducted with the intention of determining the cause of the smog incident and determining how to prevent future incidents (which can be found here). The report is then broken down into two primary sections: “Biological Studies” and “Atmospheric Studies,”. “Biological Studies” looks at the demographic makeup of Donora and Webster, a neighboring town also affected, along with the affects the smog had on the population. “Atmospheric Studies” analyzes the contaminants being put out by the three plants along the river in Donora.

[3] Snyder, “‘The Death-Dealing Smog Over Donora, Pennsylvania.’”

[4] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[5] Snyder, “‘The Death-Dealing Smog Over Donora, Pennsylvania.’”

[6] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[7] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[8] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[9] Rothschild, “Creating a Global Pollution Problem.”

[10] Snyder, “‘The Death-Dealing Smog Over Donora, Pennsylvania.’”

[11] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[12] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[13] Brian Charlton, “Cement City: Thomas Edison’s Experiment with Worker’s Housing in Donora,” Western Pennsylvania History, no. Fall 2013 (2013): 34–45.

[14] James G. Townsend, “Investigation of the Smog Incident in Donora, Pa., and Vicinity,” American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health 40, no. 2 (February 1950): 183–89, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.40.2.183; Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report.”

[15] Charlton, “Cement City: Thomas Edison’s Experiment with Worker’s Housing in Donora.”

[16] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[17] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[18] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[19] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[20] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[21] Gnora Death Case – Evidence of Causation. Accessed via flash drive from the Donora Historical Society

[22] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[23] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[24] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).

[25] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[26] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.; James McKenzie, “Woody and Cassy’s Journal: WWII and Other Dark Shadows,” Western Pennsylvania History, no. Fall 2002 (n.d.): 13–27.

[27] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[28] Gnora Death Case – Evidence of Causation. Accessed via flash drive from the Donora Historical Society

[29] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[30] H H Schrenk et al., “Air Pollution in Donora, Pa. : Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948 Preliminary Report” (Federal Security Agency, 1949).; Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[31] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[32] Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[33] No identifying information is given other than a typed caption stating the date, a visual description of image, the context of the photo, and that the photo was staged. While the photograph may have been staged, this photograph is from a series of photos taken during the smog event when a photographer documented what was happening. The phrase “set-up” does not imply that this photograph is entirely fiction, just that the photographer likely adjusted the scene in some way, such as posing figures or allowing the family to dress a certain way.

[34] While the photograph may have been staged, this photograph is from a series of photos taken during the smog event where a photographer went around the community documenting what was happening. The phrase “set-up” does not imply that this photograph is entirely fiction, just that the photographer likely moved the scene in some way, such as posing figures or allowing the family to dress a certain way. There is no evidence to show that the person being treated was not a real victim receiving actual care.

[35] “DENIES SMOG ZINC BLAME: OWNERS OF DONORA PLANT ISSUE STATEMENT STRESSING FOG.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Nov 17, 1948. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url= ?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/108253466?accountid=13626.

[36] Townsend, “Investigation of the Smog Incident in Donora, Pa., and Vicinity”; Rothschild, “Creating a Global Pollution Problem”; Andrew Maietta, Rumor of Blue Sky, 2009.

[37] Townsend, “Investigation of the Smog Incident in Donora, Pa., and Vicinity.”

[38] “1948 Smog – Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum.” https://www.sites.google.com/site/donorahistoricalsociety/1948-smog; Kunert Günter. “Lied Von Einer Kleinen Stadt.” Poem. In Wegschilder Und Mauerinschriften; Gedichte, 55–57. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 1950. https://portal.dnb.de/bookviewer/view/1019135530#page/55/mode/1up

[39] “October 14, 1949 (Page 1 of 68).” The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Oct 14, 1949. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url= ?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/1835116490?accountid=13626; “March 3, 1950 (Page 4 of 26).” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (1927-2003), Mar 03, 1950. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url= ?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/1854445072?accountid=13626; “October 31, 1949 (Page 2 of 40).” The Philadelphia Inquirer Public Ledger (1934-1969), Oct 31, 1949. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url= ?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/1835098684?accountid=13626.

[40] This quote was found as part of a document on a flash drive given to me from the Donora Smog Museum about the smog event. This quote occurred in 1967 during a Los Angeles radio interview with the mayor of Donora.

[41] Murray, Ann. “Sixty Years Ago, Smog Killed 20 People in a Pennsylvania Town. This Museum Tells Their Story.” The Allegheny Front, April 17, 2017. https://www.alleghenyfront.org/sixty-years-ago-smog-killed-20-people-in-a-pennsylvania-town-this-museum-tells-their-story/

[42] Snyder, “‘The Death-Dealing Smog Over Donora, Pennsylvania.’”

[43] “DENIES SMOG ZINC BLAME: OWNERS OF DONORA PLANT ISSUE STATEMENT STRESSING FOG.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Nov 17, 1948. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?url= ?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/108253466?accountid=13626.

[44] The year-long study was conducted with the intention of determining the cause of the smog incident and determining how to prevent future incidents (which can be found here). The report is then broken down into two primary sections: “Biological Studies” and “Atmospheric Studies,”. “Biological Studies” looks at the demographic makeup of Donora and Webster, a neighboring town also affected, along with the affects the smog had on the population. “Atmospheric Studies” analyzes the contaminants being put out by the three plants along the river in Donora.

[45] Theodore Steinberg, Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in America (Cary: Oxford University Press, 2000); Rothschild, “Creating a Global Pollution Problem.”

[46] It should also be noted that the report also investigates the meteorological conditions that caused the smog to sit in the town for several days. It compared known conditions from the incident with data collected daily from the area. It concludes that the weather event from the incident was an extreme version of “smokey mornings”. Extreme weather is then suggested to be a primary factor responsible for the incident and the report suggests that the weather should be monitored a system in place to warn of poor weather conditions.

[47] “1948 Smog – Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum.” https://www.sites.google.com/site/donorahistoricalsociety/1948-smog.

[48] “1948 Smog – Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum.” https://www.sites.google.com/site/donorahistoricalsociety/1948-smog.

[49] Rothschild, “Creating a Global Pollution Problem.”

[50] Holsopple, Kara. “What You Need to Know About Air Quality, the U.S. Steel Settlement and Temperature Inversions.” The Allegheny Front, September 1, 2020. https://www.alleghenyfront.org/what-you-need-to-know-about-air-quality-the-u-s-steel-settlement-and-temperature-inversions/.

Primary Sources:

Title: Air Pollution in Donora, Pa.: Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948: Preliminary Report

Date: 1949

Schrenk, H.H., Harry Heimann, George D. Clayton, W.M. Wexler, Air Pollution in Donora, Pa.: Epidemiology of the Unusual Smog Episode of October 1948: Preliminary Report, Washington, D.C: Federal Security Agency, Public Health Service, Bureau of State Services, Division of Industrial Hygiene, 1949

https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/31320170R/PDF/31320170R.pdf

This government report is a study that investigated the atmospheric and biological consequences of the Donora smog. This study compiles primarily quantitative data to show how the smog and air pollution affect the town. It provides me with scientific data to illustrate the conditions in Donora in the year just after the event and cross-references with this data with census data to see who was impacted. It illustrates some of the inequalities of who was affected. It also gives recommendations on how to help Donora and how to prevent such an event in the future. While it may credit the weather as the majority cause to the smog, it also blames the different sources of air pollution in and around the town.

Title: Ashe Memo to Dr. Kehoe

Date: 1949

Donora Historical Society, Donora, Pennsylvania

(Accessed via flash drive mailed to me from the Donora Historical Society)

This source, while seemingly just a brief memo to inform Dr. Kehoe about the scientists coming to Donora to conduct the epidemiology study, it also discusses a bit of Donora’s relationship with the smog and local industries prior to the smog incident in October and how it changed afterwards. It also goes over Donora’s physical location in relation to local industries – there were more than just the two factories. It also alludes to other data collected in relation to the smog – autopsies of those who died, the symptoms experienced by those affected by the smog, and data collected by the American Steel and Wire Company (and frustrations about not being able to access these findings). It is very insightful to how the incident changed Donora’s relationship with the smog and local industries.

Title: Rumor of Blue Sky Tapes 1-30

Date: 2004

Donora Historical Society, Donora, Pennsylvania

(Accessed via flash drive mailed to me from the Donora Historical Society)

These tapes compile interviews with 25 residents of Donora that survived that smog incident. It covers a wide range of topics gathering narratives about what the town was like before, during, and after the event from these survivors. These interviews were used to make a documentary about the event called Rumor of Blue Sky. There are about 15 hours of interviews available through the Donora Historical Society. It will provide me with narratives, thoughts, and feelings from those who experienced this event.

Title: Bill’s Smog Story

Date: 1998

Donora Historical Society, Donora, Pennsylvania

(Accessed via flash drive mailed to me from the Donora Historical Society)

This video is a three-minute news clip about how Donora was honoring the 50th anniversary of the smog incident. The video features local news anchors going to Donora and talking to some of those involved with the incident. When discussing the anniversary, a high school student discusses how the town initially responded to the event along side the anchors who go over the current thoughts and feelings the community has in regard to the event. While honoring the local disaster, the shift in feelings about the event is also recorded in this news clip.

Title: USS-PA Week Open House

Date: 1948

Donora Historical Society, Donora, Pennsylvania

(Accessed via flash drive mailed to me from the Donora Historical Society)

This is a book produced by the American Steel & Wire Company that accompanied an open house for the facilities in Donora. The piece briefly goes over the history of the facilities in Donora. It also puts the work happening in the facilities into language that is easily digested by the average person. It allows me to start to see what was occurring in the factories in Donora.

Secondary Sources:

1. Jacobs, Elizabeth T., PhD., Jefferey L. MD, and Mark B. Abbott PhD. “The Donora Smog Revisited: 70 Years After the Event that Inspired the Clean Air Act,” American Journal of Public Health 108, S2 (2018): S85-S88.

- This piece, while also looking at the legacy of the Donora Smog, focuses on the long-term health and pollution consequences of the event. It gathers quantitative data on deaths from cancer and cardiovascular disease in the area from 1948 to 1957. Provides quantitative and health analysis that can be used in own project.

2. Magoc, Chris J. “Reflections on the Public Interpretation of Regional Environmental History in Western Pennsylvania,” The Public Historian 36, issue 3 (2014): 50-69.

- This article is very rich in information about Western Pennsylvania’s relationship with its environment and environmental history, arguing that region is filled with histories that link to modern environmental concerns and can challenge the views of residents and visitors. It discusses the region’s relationship with this history, which is at times contentious and features a section on the work of the Donora Smog Museum. It sees public history as an important tool to bridge the present and past. This piece starts to look into public memory and public history in the region of interest, but I want to go more specific with only Donora.

3. Rothschild, Rachel Emma. “Creating a Global Pollution Problem.” In Poisonous Skies: Acid Rain and the Globalization of Pollution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- This book chapter looks at the construction of pollution, specifically air pollution, on the global scale – even noting the Donora Smog and other similar events as important moments in understanding smog and air pollution as an important environmental and health concern in the post-WW2 world. This provides me with larger, contextual insight to how air pollution and smog was regarded before and after the Donora Smog.

4. Snyder, Lynne Page. “’The Death-Dealing Smog over Donora, Pennsylvania’: Industrial Air Pollution, Public Health Policy, and Politics of Expertise, 1948-1949,” Environmental History Review 18, no. 1 (Spring 1994): pp. 117-139.

- This piece looks at the historical legacy of the Donora Smog focusing on the impact it had on federal air pollution policy, power of corporations over local economies, and deployment of expert knowledge in legal cases. It provides me with the political legacy of the Donora Smog.

5. Steinberg, Theodore. Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in America. Cary: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- This book examines the consequences of governments and corporations using the argument “act of God” to refuse responsibility for disasters and refuse to acknowledge the human and societal factors that go into disasters and who is affected by them. Act of God was the defense used in the lawsuit after the incident and this will provide me more context for understanding this argument and its ramifications.

Image Analysis:

Project Site: Donora 1948 Smog

Oxygen Delivery: Age and Class as Factors of Affection by Smog

In 1948, a weather phenomenon caused the smog being emitted from three industrial plants around Donora to descend into the town causing thousands of residents to become ill, killing about twenty residents during this four-to-five-day episode. Residents who were severely affected by the smog quickly filled the local hospital. Not everyone who needed medical support or treatment because of the smog was able to visit the hospital. In response, members of the community took it upon themselves to deliver oxygen to other community members more severely affected by the smog and unable to be treated at the hospital. On November 1, 1948, a photographer joined a group of firefighters as they took oxygen tanks to community members, making sure they had access to clean, breathable air. November first was when the smog started to break up in Donora because of rain. This photo depicts a group of three firefighters helping a man, and assumably grandfather, receive clean air from the oxygen tanks while the man’s family stands around the couch watching the process. No identifying information is given other than a typed caption stating the date, a visual description of image, the context of the photo, and that the photo was staged. While the photograph may have been staged, this photograph is from a series of photos taken during the smog event where a photographer went around the community documenting what was happening. The phrase “set-up” does not imply that this photograph is entirely fiction, just that the photographer likely moved the scene in some way, such as posing figures or allowing the family to dress a certain way. There is no evidence to show that the person being treated was not a real victim receiving actual care. This photograph does show that there were inequalities involved with the smog. The photograph shows that during the smog episode, not everyone was affected equally nor did everyone have equal access to care.

The focal point of the image shows a man holding an oxygen mask onto another man, who is laying on the couch. The man on the couch, while the viewer cannot see much of him, there are details in the rest of the photograph that allow the viewer to know more about this man. Behind him there are an adult couple and three younger persons. They can be assumed to be his child, spouse, and grandchildren. The entire family, except the baby, is staring at the man on the couch with serious expressions. Since the photographer had the entire family present so that the view can assume the man to be a grandfather, we can also assume that he is an older gentleman. This detail is important since residents who were older tended to be more severely affected by the smog. The man’s exact condition is unknown; but if he is receiving oxygen, then it must be at least somewhat severe. The men who are operating the oxygen machine are seemingly in their thirties or forties. No one else in the photograph is shown to be elderly except for the man on the couch. That man is the only one actively receiving medical care due to the smog. This is a visual representation of the general trends of who was affected by the smog. Generally, those who were fifty years or older were more severely affected by the smog. This does not mean that the other people in the photo were not affected by the smog at all or have long-term health effects, it shows that they did not require immediate medical attention because of the smog. No one else in the photo is visibly affected by the smog.

The captain on the photo allows the viewer to know some information about who is delivering the oxygen to the man. The three men in the photograph working the oxygen machine are part of emergency crews. These emergency crews were mostly composed of local firefighters volunteering to help others in the community. These men were not medical experts. Without of the captain, there would be no way to know who these men were in the photo. Knowing who they are is important to understanding another inequality in Donora during the smog episode. The longer the smog sat in Donora, the more people breathed it into their bodies, and the more it affected them. As more people were affected by the smog and required medical attention, they initially went to the hospital for treatment. Yet the local hospital could not support all the people coming in with respiratory ailments. Not every resident who needed medical care was able to receive it. Therefore, the emergency crews went around the town delivering oxygen to residents. This was a community response to inequality, which was exasperated by the smog affecting so many residents. Those who received care, but not in the hospital, received it in their homes. While the background is mostly covered by the family and the men, there is enough visible to recognize that this man is being treated in a house. He is laying on a couch with a quilt over the back and behind the boy holding the baby, there is a fireplace with a mantle displaying family photos.

Even being treated in a house represents a form of inequality. The photo may not reveal enough of the home to show its physical condition, homes were a factor when it came to severity of affection from the smog. A report from a study conducted during the year following the episode revealed that the quality of house one lived it affected how the smog affected them. The study did not break down the specific factors that caused this relationship, but it did highlight data that showed a trend that residential areas with higher quality homes were less severely affected by the smog and residential areas with lower quality homes had higher rates of severe affection from the smog. The photographer does not reveal the quality of the house in this photo, so the viewer cannot assume house quality as a factor for why this man is receiving medical care. Yet if it is, one may ask how would him being in a home with low quality air or insufficiently filtering out the smog affect his ability to be treated at home? For how long did the man use the oxygen machine? These are questions about the scene that the photograph does not answer, but further research into other photos from the series or other materials available in the archive may assist in further understanding these factors.

This photograph helps the viewer understand and visualize some of the inequalities that affected this smog episode in Donora. While the inequalities may not be immediately recognizable, one’s age and class status were factors that contributed to how severely a resident was affected by the smog. The photograph shows an elderly man receiving air from an oxygen machine that was delivered by an emergency crew. The fact that the photographer chose to photograph the elderly man receiving air, provides an image for who was thought of as the standard group to be most severely affected. The reason the man is being treating in his home is because he could not access the local hospital. While the reason for lack of access is not given, it is likely due to the overcrowding that occurred in the local hospital preventing residents from accessing it. These emergency crews were a response to this community response. These factors show that while the smog sat in the town affecting everyone, there were societal factors that influenced how severely a resident was affected by the smog. The entire town responded to the event, even though not everyone was equally affected by the smog. This also only shows immediate inequalities affecting the immediate event. It does not show inequalities involved with the long-term affects of the smog. Everyone needs breathable air to live, but during this moment, not everyone had access to clean air.

Data Analysis:

During the final week of October 1948, a thick layer of smog coated the valley of the West bank of the Monongahela river, where the town of Donora is located. Not only did this smog reduce visibility in the town, but it also caused those living in the town to experience sickness. As a result, a year long study was conducted with the intention of determining the cause of the smog incident and determining how to prevent future incidents (which can be found here). The report is then broken down into two primary sections: “Biological Studies” and “Atmospheric Studies,”. “Biological Studies” looks at the demographic makeup of Donora and Webster, a neighboring town also affected, along with the affects the smog had on the population. “Atmospheric Studies” analyzes the contaminants being put out by the three plants along the river in Donora. The year long study concludes that age, residence, and previous health status affected how severely the smog affected someone and determined that a weather phenomenon preventing air pollution from leaving the valley is what caused the illnesses. It could not determine that a singular pollutant was responsible for the illnesses and deaths, but that it came from the exposure of a cocktail of pollutants from both the local plants and the local traffic on the streets, river, and railroads. This report orients itself as a scientific and objective study shying away from suggestions that may seem political in nature. The data only shows inequality of who was affected by the smog and how it affected different populations, but does not do further analysis of causes of the inequality, yet the data does still show data suggesting that one’s socio-economic status was relevant to how they may have been affected by the smog.

Using data from the 1940 census, the demographics of Donora are broken down and are compared to national, state, and South-West Pennsylvania trends. Overall, only about 42.7 percent of the population reported being affected by the smog. When crossing referencing the demographic data with data from interviews and medical records of those who reported being affected by the smog, trends begin to emerge. These trends lead the study to conclude that age, residence, and previous health status were linked to how severely the smog affected someone. Generally, as the age of persons increased, so did the percent reporting affection from the smog. All age groups above and including 35-39 have over half the respective population reporting affection from the smog. The report also broke the population into residence districts, which showed that district one in Donora and Webster had higher rates of affection from smog. Yet it only crosses residence with age of residents, it does not consider any other factors than may influence affection from smog. Finally, previous health status was noted as a significant factor for affection. Persons who were already inflicted with a cardiovascular disease or condition also reported higher rates of affection from smog. This also relates to housing conditions. Residences that had higher amounts of affection also had the least amount of satisfactory housing. While there is no chart to display this data, the report states that as the number of dwellings rated as satisfactory and above increase, the percentage of reports decreases. While the report does suggest further research into housing conditions, it does not suggest improving housing as a way to prevent such an incident in the future. Yet for housing to be such a significant factor in the study for degree of affection shows the reader that one’s socio-economic status was also important for determining how the smog affected someone.

Throughout the year after the incident, weather and atmospheric tests were done. These tests analyzed the pollutants being put into the air by the local plants. The report broke the pollutants down into the average amount found in the air and broke down the amount of each pollutant coming from each plant. This report does conclude that none of the plants individually are putting out amounts of pollutants that are considered harmful to the population or go above current (current being regulations in 1949) regulations, it does not rule out the possibility of the cocktail of pollutants being emitted from the factories along with the pollutants from traffic from the river, railroads, and streets as being harmful to the population. In the “Recommendations” section, reducing the pollutants, especially sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, from the plants are directly listed as a way to prevent such an incident. However, it does not suggest how the plants go about lowing the emissions of pollutants. The report shies away from making specific suggestions on how to regulate the plants via policy or technological changes to the plants. The report makes no suggestions that could be read as political, yet the fact that the pollutants from the plants are not ruled out as being harmful and that reduction measures are suggested also shows that the corporations owning and running the plants are not innocent in the issue.

The report also investigates the meteorological conditions that caused the smog to sit in the town for several days. It compared known conditions from the incident with data collected daily from the area. It concludes that the weather event from the incident was an extreme version of “smokey mornings”. Smokey mornings are when there tends to be less wind to blow smoke out of the valley along with air temperatures preventing the smoke from rising – these mornings may also be accompanied with fog. While these were not uncommon, it is uncommon for the smoke to stay in the valley past noon. In this extreme smokey morning, there was little wind and the air was not rising out of the valley, trapping the smog in the valley. Along with noting the weather conditions that caused this incident, it also notes that on days with less or slower wind there were higher concentrations of pollutants in the air. This extreme weather condition is likely to occur, but the report says it would only be in intervals of ten to fifteen years. Extreme weather is then suggested to be the primary factor responsible for the incident and the report suggests that the weather should be monitored a system in place to warn of poor weather conditions.

Once the report discusses the primary cause of the incident as extreme weather mixed with significant amounts of pollutants, it suggests that while the plants were responsible, it was not primarily their fault. Still, it does suggest a reduction of pollution from the plants. While it credits the weather for trapping the smog, the data seems to also imply a reliance on the weather to push the smog and pollution out of the area. It also fails to acknowledge the fact that a weather phenomenon such as this would not have been dangerous if the plants were not emitting harmful pollutants. It also vaguely suggests the importance of socio-economic standing when looking at rates of affection from the smog, yet the report shows evidence of it. While the primary piece of evidence is the housing conditions, it also notes a higher mortality rate for black persons affected than white persons affected from the smog. Yet it also states multiple times that race was not an important factor for determining affection, which means there was some sort of inequality in the treatment of white persons affected and black persons affected. This report primary orients itself as an objective, scientific report driven by data, but it still shows remnants of issues of societal inequalities as factors for who was affected by the smog.