A Tale of Two Cities: Stories of Race, Place, and Lead Contamination in Trenton, New Jersey and Levittown, Pennsylvania, 1950-1960

by Gabriella Zalot

Site Description:

“Trenton makes, the world takes.” Although this reference to Trenton’s successful, industrial history remains emblazoned across the Lower Trenton Bridge, the current reality in New Jersey’s capital is much bleaker than its bustling past. In addition to the myriad problems confronting many northeastern cities, Trenton is facing an environmental health crisis by way of elevated levels of lead. Caused most acutely by the prevalence of chipping lead paint in rental homes, the levels of lead in affected Trenton residents are much higher than the levels in surrounding communities. This project will specifically examine the history and causes of health disparities between Trenton and Levittown, Pennsylvania, a suburban, racially restrictive town only a ten minute trip from Trenton by way of the Lower Trenton Bridge. Although typically only studied as separate entities, how and why are Trenton and Levittown connected historically? How did the racial policies, as implemented by both the U.S. government and the Levitts alike, cause the formation of an environmental inequality (lead contamination) between Trenton and Levittown? Not only does this project seek to uncover the forces at play between 1950s Trenton and Levittown, but it serves to illustrate America’s bigger problem of disproportionate environmental burdens being placed on urban, minority communities.

Introduction

After a move to follow a job, Russ Gambino, a Long Island native, became one of the first to settle in the “perfectly planned” suburb of Levittown, Pennsylvania. Gambino spent his days laying tiles in houses within the new construction site and made “damn good money” while he was at it.[1] Returning from work every night to a peaceful house on Leisure Lane, Gambino was thoroughly content with his life. Even as further job opportunities came his way, Gambino remained steadfast in his desire to remain in the idyllic suburb of Levittown. Comforted by the sense of community and the Italian market that he passed by on his way to work every morning, Russ felt right at home in the town tucked into the bend of the Delaware River, a mere 8 miles from then vigorous, Trenton, New Jersey. Fast forward over 70 years later and I now live in that same house, in the same town, that Russ Gambino spoke so highly of. While times have changed, a similar sense of community and comfort still characterizes Levittown, the quintessential suburban development.

My mother, Amy Zalot, also resides in the same house that Gambino did all those years ago. However, her reality in peaceful Levittown, is shattered every morning as she makes her way across the Delaware River and to her school, Grant Intermediate, located in Trenton, New Jersey. Working in Trenton Public Schools, Amy sees a lot of problems that are not present in cross-river Levittown, but one unexpected issue that she and her students face daily has been laying hidden underneath the surface. Lead, a highly toxic substance that has the potential to cause lasting cognitive effects, especially in children, was recently found in the soil that the school was built on. Tracing the lead to the remnants of a pottery factory that once operated on the land that the school now occupies, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notified Grant’s faculty, including my mother, of the problem in January 2024. Although the EPA representatives found that immediate action was required, Amy remembered the EPA singing a different tune. Instead of responding swiftly to the problem she recalled that the EPA, “did not offer to test the students at the school” and that “nothing was offered to staff or families by the district.” In addition to not doing much to monitor the health of those already within the Grant community, she felt that “they don’t really have a timeline for completion and did not say what a final solution would be.”[2] While Amy is able to travel back across the river at the end of the day and retire to her lead-free Levittown home, the students that attend her school do not have the same luxury and must instead face the realities of the lead that not only contaminates their school, but many of their homes as well.

While these two stories, one describing the tranquility of living in Levittown and the other detailing the plight of Trenton’s children and schoolteachers, may seem disconnected, there is a history that not only brings the two towns together in the past, but in the present as well. Lead exposure, a serious health problem wreaking havoc in many American cities, is often encountered when children ingest lead laden paint chips, falling away from the walls of older, likely deteriorating homes. Both communities, Trenton and Levittown, have housing stocks that were primarily built prior to the passage of the Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act in 1978, meaning that those who live in those homes are at risk for ingesting the dangerous dust of chipping lead paint.[3]The story does not end however, with both communities experiencing the negative effects of elevated lead exposure. Instead, Trenton, changed significantly by the development of Levittown, has had a much more difficult time keeping its citizens protected from the dangers of lead.

This history that caused Trenton to bear a disproportionate environmental burden, raises key questions regarding the connection between the federal policies of the 1950s and the reality of minority communities today. Although typically only studied as separate entities, how and why are Trenton and Levittown connected historically? How did the racial policies, as implemented by both the U.S. government and the Levitts alike, cause the formation of an environmental inequality (lead contamination) between Trenton and Levittown? Why are these lead discrepancies so startling and what is its relationship between low-income rental housing and lead contamination? Answering these questions and more, I have concluded that the racially discriminatory 1952 construction of Levittown, Pennsylvania caused the permanent alteration of Trenton, New Jersey’s economic and demographic trajectory. These changes in economic and demographic realities then contributed to Trenton’s persistent, and unequal, issues regarding lead contamination and exposure.

There is considerable literature surrounding the aforementioned issues, including work on Trenton’s long history, the suburbanization of Levittown, and the detrimental health effects of elevated blood lead levels. New Jersey’s capital city, Trenton has long been regarded as merely another example of urban decay, with crime and poverty running the show.[4] However, many do not realize that before the construction of Levittown, Trenton was in a much different, more successful place, with business opportunities abounding. Similarly, Levittown is widely known for its role in popularizing suburbanization and enacting divisive, racist policies, but is not usually associated with altering the economic and demographic future of neighboring Trenton.[5] Lead, the key component that ties together these two cities today, has also been left out of their interconnected story. While discussed in detail in other cities, like Detroit and New York City, the connection between redlining and home accessibility and lead has not been covered in much detail as it pertains to Trenton and its relation to Levittown.[6] Although the histories of Trenton and Levittown have both been studied extensively, the connection between the two communities has been sorely neglected. Additionally, the health effects of lead have been discussed by scholars and community groups alike, but the difference between these two communities’ levels of exposure has not been covered in much detail.

This project looks to thread together the stories of Trenton and Levittown, uncovering the unequal burden that low income, minority communities like Trenton tend to bear in terms of environmental health hazards and the ways in which the middle-class white residents of Levittown are able to escape such hazards. Beginning with Trenton’s long, rich history of industrial prosperity that predated the construction of Levittown, I will then dive into the historical connections between these two communities. With these connections established, I will then expose the surprisingly vast differences in lead exposure between the two communities. Then, I will discuss the cause of these differences; the racially divisive housing realities perpetuated by the involvement of the federal government and the stubborn, racist nature of the Levitts and many of those within the community. Finally, I will examine the connection between these racist housing policies of the past and the current reality of depleted home ownership in Trenton, highlighting the role of rental properties and the landlords’ inability to keep their residents safe from chipping, lead paint. While the people of Trenton have attempted to address these problems, their plight is part of a larger history of environmental injustice where low-income communities of color bear disproportionate burdens.

Separated by the Delaware, Connected by History

The capital of New Jersey, Trenton has been incorporated as a city since November 13, 1792. Commonly known as the site of George Washington’s famous Delaware River crossing and ensuing victory over the Hessians in December of 1776, Trenton quickly grew into a prominent center of industry.[7] During the 19th and early 20th centuries Trenton thrived, welcoming companies working in the transportation, arms, automobile, iron, lock, gold and silver, and pottery industries. Incorporating three pottery works, the National Pottery Company, the New Jersey Pottery Company, and Union Pottery Company, all within the year of 1869, the production of ceramic goods became a key facet of the Trenton economy and a pivotal environmental factor later on in the city’s history.[8]

Following the rapid industrialization in the mid to late 1800s, Trenton continued to make its economic mark into the Mid-Twentieth Century. One of the greatest markers of this industrial power was a new addition to the Lower Trenton Bridge that was completed in 1917. Originally constructed in 1806 as the first bridge to reach across the Delaware River, the Lower Trenton Bridge went through many iterations before reaching its most notable renovation in 1917. It was then that the phrase, “Trenton Makes, the World Takes,” was found emblazoned across the length of the bridge. Adopted as the city’s official moniker seven years prior, “Trenton Makes, the World Takes,” served to recognize the city’s commitment to manufacturing and trade.[9] While this turn of phrase may seem misleading to those who cross the bridge today, many of whom traverse it to reach the suburb of Levittown, it was quite an accurate representation of the city before the Levitts moved in across the border.

Separated from Trenton by only a short ride over the Trenton Makes Bridge, the second of the Levittowns built by Levitt & Sons, Levittown, Pennsylvania is situated rather close to both Trenton and Philadelphia on land that was previously home to vast spinach farms. Construction on this new community was proposed in 1951 and the first home was completed in 1952. Looking back, it has been noted by historian Dianne Harris that “the Levitts designed, built, and marketed their homes to an exclusively and generically formulated white audience,” with spacious yards, an abundance of fruit trees, and kid friendly amenities aplenty. Included within these white-coded designs were six architectural options, including: the Levittowner, the Rancher, the Jubilee, the Pennsylvanian, the Colonel, and the Country Clubber. All homes followed these specific models and were broken into 41 sections, organized by letter and surrounded by a circular drive. For example, every street in the “Lakeside” section started with the letter L and all the streets in the “Pinewood” section started with the letter P.[10] As Harris recounts, these houses and sections were built as “the obvious antithesis” to “cramped inner-city apartments or row homes in nearby cities like Philadelphia and Trenton.”[11]The Levittown community, sometimes referred to as being “perfectly planned”, was created as a place for white families to safely and affordably grow and enjoy the new culture of homogeneity.

Despite, or perhaps because, Levittown was so “perfectly planned,” nearby Trenton’s population was greatly impacted by the arrival of the new town. According to a January 24, 1954 news article written by Luther P. Jackson, “1,482 registered voters moved across the river to Bucks [County] between the November 1952 and November 1953 elections, the vast majority of them from Trenton.” Drawing on the analysis of Samuel Naples, secretary of the Mercer County Board of Elections at the time, the evidence indicates that “most of these migrants moved into the huge Levittown and Fairless Hills housing developments,” exposing the role that the construction of Levittown played in the population change taking shape in Trenton.[12]Not only was this exodus being highlighted by newspapers at the time, but Trenton’s census records revealed similar trends. As reported by the 1950 census, Trenton’s population was around 128,009.[13] However, by 1960, the population was found to be only 114,167, decreasing by 10.8%, a considerable amount. These statistics, considered in conjunction with the fact that the population of the Trenton Metro Area, an area that included Levittown, grew by 15.6% during those same years, suggests that people were not leaving the region, but were simply moving out of Trenton. [14]

These changes in population between Trenton and Levittown, spurred by new housing opportunities, were even further exacerbated by the economic opportunities afforded to people by the Fairless Hills Steel Mill. As evinced by a 1953 documentary detailing the mill, the Fairless Hills Steel Mill was constructed along the curves of the Delaware River, only miles away from the heart of Levittown, for its proximity to fresh water, East Coast ports, connectivity to roads and railroads, and the reality that there were “plenty of people in the community who could be good steel makers.”[15] Covered again through the work of Luther P. Jackson, it was posited that, “U.S. Steel’s new $400,000 Fairless Works opposite Trenton may spark one of the biggest booms in [the] area’s history.” Despite the positive impact that the mill was expected to bring, Trentonians realized that these benefits stopped where the Delaware River started, not providing Trenton with the same economic benefit as its Levittown counterpart.[16]Instead, Jackson notes that “Trenton has absorbed many of Bucks County’s headaches without sharing in its prosperity.”[17] While it was clear that Trenton did not reap the same economic benefits of their cross-river neighbors, what were these “headaches” that Jackson alluded to?

Two Communities: One Lead Crisis

One of these headaches spurred by the construction of Levittown and the lure of the Fairless Hills Steel Mill, although not yet realized at the time of Jackson’s writing, was the incredibly high level of lead contamination that would plague Trenton for years to come. While any lead contamination is damaging to individuals and their communities, the levels of lead contamination in Trenton are extremely high, especially when considered in comparison with their cross-river neighbor and historical bedfellow, Levittown. Both communities, Trenton and Levittown, have had their children tested for elevated blood lead levels (EBLLs), with the most recent study done in Trenton being from 2019 and the most recent from Levittown being conducted in 2014. As noted in the “Childhood Lead Exposure in New Jersey Annual Report (2019)”, 5.9% of children under 6 tested in Trenton had EBLLs, considered in this case to be any level above 5mg/dL.[18] While this may not seem like a percentage worth worrying about, Trenton has the second highest percentage of children with EBLLs in the entire state of New Jersey. Even more startling, Trenton’s percentage of children with EBLLs is almost double that of Levittown’s, with the Pennsylvania “Childhood Lead Surveillance Annual Report (2014)” finding that the percentage of Levittown’s children with EBLLs is only 2.16%.[19]

Although lead was formerly a common ingredient in household paint, it is now known to be a toxic substance with lasting, adverse health effects. One of the most worrisome aspects of lead contamination is the fact that no effective treatments have been found to negate its effects. Typically studied in children, these effects include “intellectual deficits, neuro-behavioral disorders, developmental delays, and lower academic achievement.”[20] These effects can severely hinder a person’s quality of life and since there are no effective treatments, will follow the person throughout their entire lifespan. In addition to the individual effects that are caused by lead contamination, there are also social consequences associated with the toxin. According to research done by Isles Inc., a Trenton based advocacy group, “children with lead in their blood are seven times more likely to be involved within the juvenile justice system.” Additionally, “each child affected by lead costs taxpayers up to $32,000 per year in special education, criminal justice, and healthcare costs.”[21] With both criminal justice and the use of taxpayer dollars being priorities in most urban communities, including Trenton, it is tragic that the city has been so heavily impacted by lead contamination.

Racial Inequalities Prevail and Contribute to Lead Disparities in the Process

Although the connected past of Trenton and Levittown may seem removed from the current lead crisis plaguing Trentonians, the racist policies perpetuated by the federal government, the Levitts themselves, and those who called Levittown home, acted as the catalyst for these present-day environmental inequalities. Even though the 1948 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer ruled that courts could not uphold racially restrictive housing covenants, racist realities prevailed in Levittown for decades to follow.[22]

The first step in creating the racially polarized housing market that barred black Trentonians from making the jump to Levittown and ultimately perpetuated environmental inequalities, was the formation of the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) on June 13, 1933 by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR). As an entity that refinanced mortgages, scholar Kenneth Jackson remarked that, “the HOLC had to make predictions and assumptions regarding the useful or productive life of housing it financed.” This focus on prediction eventually guided the corporation to employ the findings of a 1939 study entitled, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities. Keeping the lessons from this study in mind, particularly that “physical deterioration was both a cause and an effect of population change,” redlining maps, marking an area as A, B, C, or D grade, perpetuated racially stratified housing. This system of grading can be seen below with a redlining map of Trenton. Here, one can see that the inner-city section of the city, an area with a higher percentage of African Americans, has been highlighted in red, designating these areas as “D” grade. Taking these biases even further by allowing the creation of all-white suburbs, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), along with the Veterans Administration (VA), “hastened the decay of inner-city neighborhoods by stripping them of much of their middle-class constituency,” precisely what happened in the case of Trenton and Levittown.[23]

Fig. 1 can be found at: Mei-Singh, Laurel. “Sowing the Seeds of Environmental Justice in Trenton.” Highwire Earth, September 13, 2013. https://highwire.princeton.edu/2018/09/13/sowing-the-seeds-of-environmental-justice-in-trenton/.

With the FHA insuring “long-term mortgage loans made by private lenders for home construction and sale,” Levittown was helped tremendously by their programs. According to The Plaindealer, a Kansas City paper that was part of the Associated Negro Press News, “of 4,480 mortgage loans closed in 1953 for homes built in Levittown, all except five were with some sort of government aid, either GI loans or FHA insurance.” Despite this large boost that Levittown garnered from the federal government, none of the homes backed by FHA loans were made available to African Americans. Instead of these loans helping all Americans, including African Americans, reach their goals, the presence of these loans in Levittown “seriously restricted job opportunities for Negro workers in the steel and other industries being introduced.”[24] Barred from entry into Levittown by the federal government, black Trentonians were forced to remain within the confines of the city.

As the Fairless Hills Steel Mill and the FHA backed construction of Levittown pulled white Trentonians away, the number of African Americans living in Trenton increased, although their housing stock did not. According to another one of Luther P. Jackson’s writings on Trenton, “between 1940 and 1950 the city’s non-white population climbed from 9,340 to 14,532 which was the main cause of Trenton’s overall increase of 3,312 persons.”[25] This trend continued into the 1950s with the percentage of Trenton residents who were non-white growing from 11.4% in 1950 to 22.6% in 1960, almost doubling their share of the population.[26] Originally flocking to Trenton for the abundance of World War Two defense jobs that were in the area, African Americans continued to move to the city even as job opportunities began to diminish.[27]Despite the increase in population size, housing was not made available for black residents of the area. In 1954 City Counsel Louis Josephson recounted for example, that “the [black housing] shortage [was] so acute that in one house in South Trenton Negroes [were] ‘sleeping in closets.’”[28] With an increase of African Americans moving into Trenton there needed to be a comparable increase in the amount of housing available for African Americans.

However, there was no such increase in available housing, with the city of Trenton not getting any larger and Levittown, boasting a booming population, not providing units for non-white populations. Although around 30 percent of the first 7,500 homes sold in Levittown were filled with former residents of Trenton, none of these cross-river movers were black. While over 17,300 housing units were eventually built in Levittown, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) only allocated 325 units to accommodate non-white residents to be built in this area at the time. This lack of housing for non-whites was felt acutely by black residents of Trenton as Luther P. Jackson reported that “none of the city’s 15,000 Negro residents [were] joining [the] exodus” to Levittown. Instead of being able to spread out and move to the budding suburbs, African Americans were relegated to the cramped, dirty quarters of urban Trenton.

In addition to federal programs luring white Trentonians across the river to Levittown and relegating black residents to Trenton, the Levitts themselves and many who called the community home, also perpetuated racial fault lines and inequality through their own actions. While their original mandate that “the tenant agrees not to permit the premises to be sued or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race” was eventually struck down in courts, the Levitts continued to sell their homes exclusively to white buyers.[29]Widely known at the time that Levittown was a community for only white homeowners, “‘a large majority’ of the residents moved there because there were no Negroes in Levittown.”[30]Not only were these residents worried about racial mixing and what that would entail for their families, but their impressions were also shaped by the view, perpetuated by redlining, that African Americans moving into a neighborhood caused property values to deteriorate. These fears were realized eventually, as the first African American family moved into town.

Content with their insulated, homogenous community, many Levittown residents incited violence when in 1957, Dogwood Hollow became the “home of Mr. Myers and his family, the first colored family to buy a home in the 15,000 unit ‘planned community’.”[31] For more than a week, mobs of Levittowners, organized by James Newell, the executive director of the Levittown Betterment Committee, gathered along Haines Road and threw rocks at the Myers’ home. As seen in the photograph below, the protests contesting the addition of the Myers family to the neighborhood had a very distinct look. Here, there is a homogenous group of mostly men, sporting relaxed grins. Instead of looking angered or tense as many protestors would, the people in this picture seem content with the fact that their voices would soon be heard, and the “correct” order of things would be restored. The mere presence of children also suggests that those in attendance believed that these protests were appropriate, safe, and potentially a place to pass down specific, racist values to their kids.

Fig. 2 can be found at: Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. Crowd protests African-American family from moving into Levittown (1957). Temple Digital Collections. Temple University. Accessed 2024. https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll3/id/4481.

While according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, “the board of directors of the Friends Service Association reaffirmed its position in ‘favor of equal opportunity for employment and housing in the Delaware Valley area,’” many other Levittowners described their fears that allowing black residents to move in would decrease the value of their homes.[32] This theory, that a black population would lead to deterioration in home values, can be traced directly back to the influence of the HOLC and FHA. Overall, the influence of these federal programs, along with the push back of Levittown residents against the addition of any black neighbors, perpetuated a racial division between the urban space of Trenton and the sprawling suburbia of Levittown.

Lead and the Unhealthy Homes of Trenton

These 1950s differences between housing availability for whites and blacks in the Trenton Metro Area have now manifested themselves as integral pieces of the Trenton’s lead crisis, despite the similarity in the overall age of each community’s housing stock.

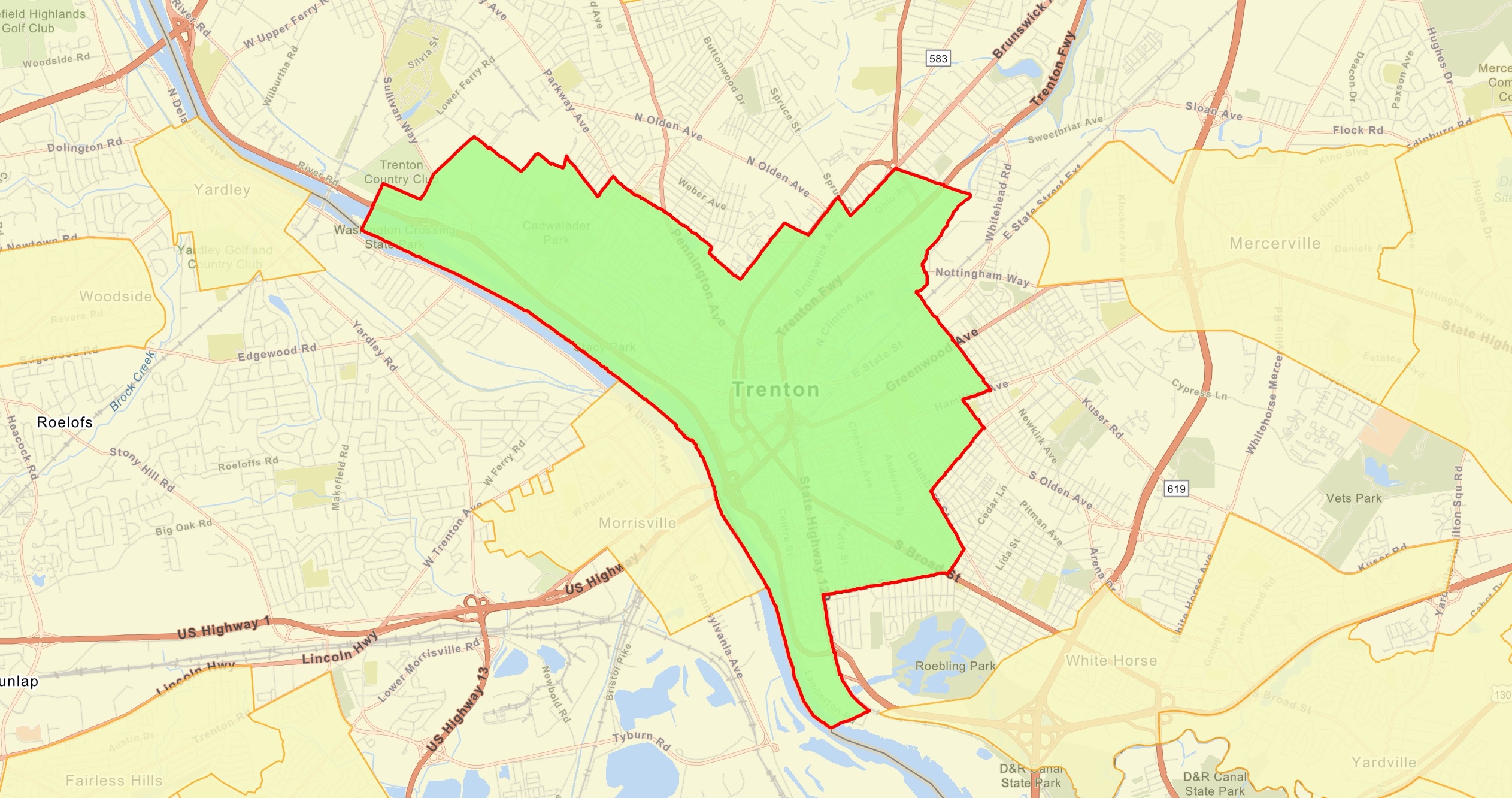

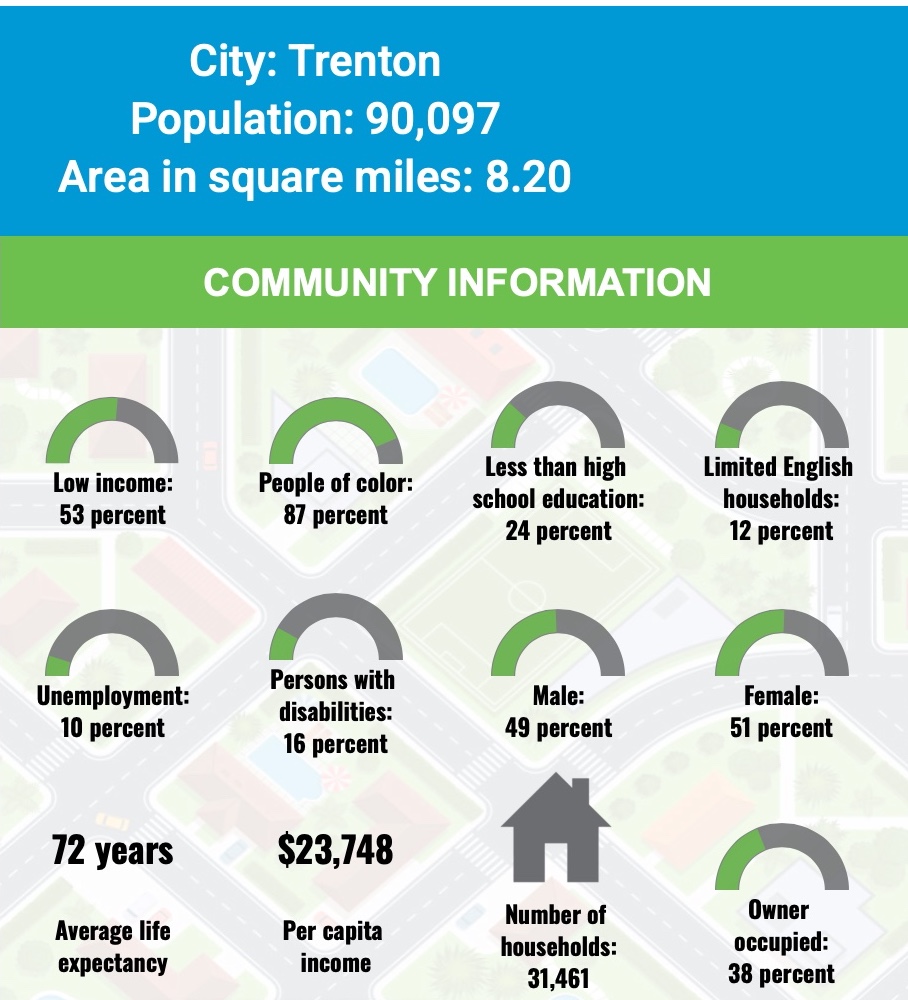

Considering the vast difference between the prevalence of EBLLs in the children of Trenton and Levittown as noted earlier, it seems surprising that according to EJScreen, the EPA’s environmental injustice platform, Trenton ranks in the 88th percentile nationally in terms of potential lead exposure and Levittown in the 91st percentile.[33] However, EJScreen’s projections, which measure the “percent of housing units built before 1960, as [an] indicator of potential exposure to lead paint,” do not consider the impact of each city’s demographics and their effect on the actual contamination rates of residents. Trenton, a modestly sized city of around 90,000 people occupying an area of 8.2 square miles, is 53% low income, with an average per capita income of $23,748. The population is 87% people of color, with only 38% of residents owning their homes. With such a low number of residents owning their homes, this suggests that a vast majority of Trentonians are renters, beholden to the whims of their landlords. These demographics are a continuation of the concentration of low income, people of color who were forced to remain in the city after Levittown was built.

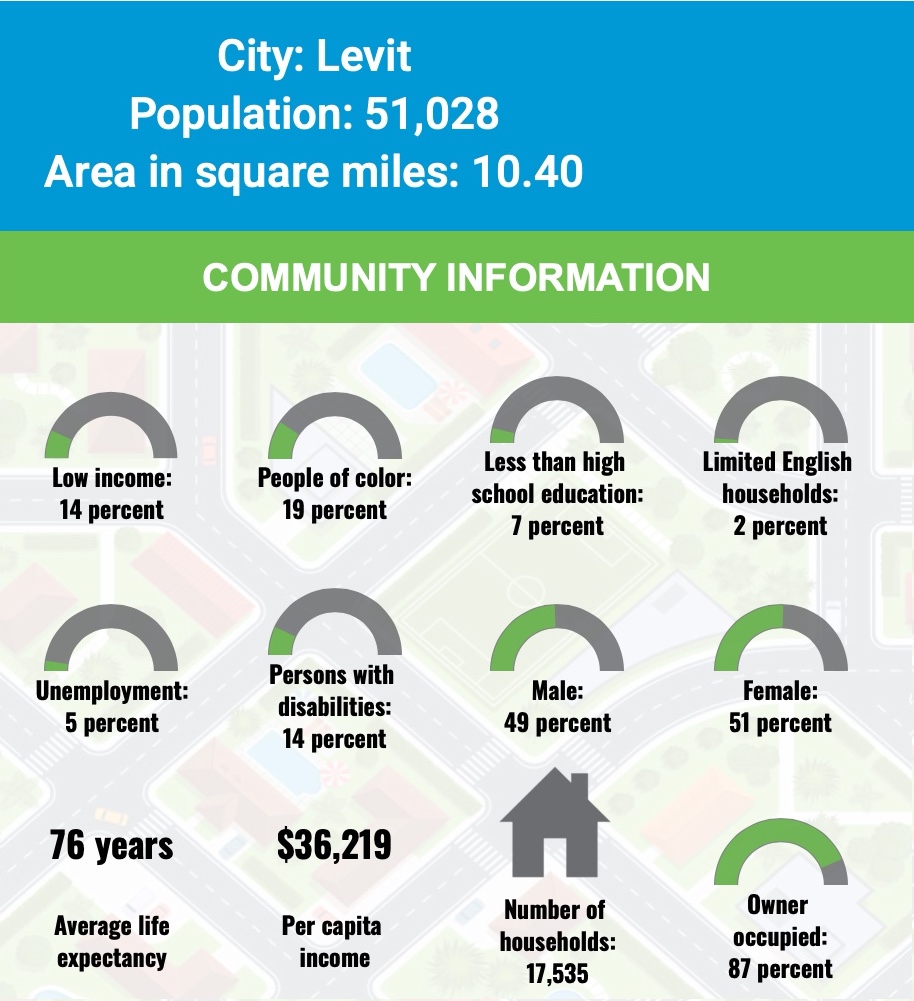

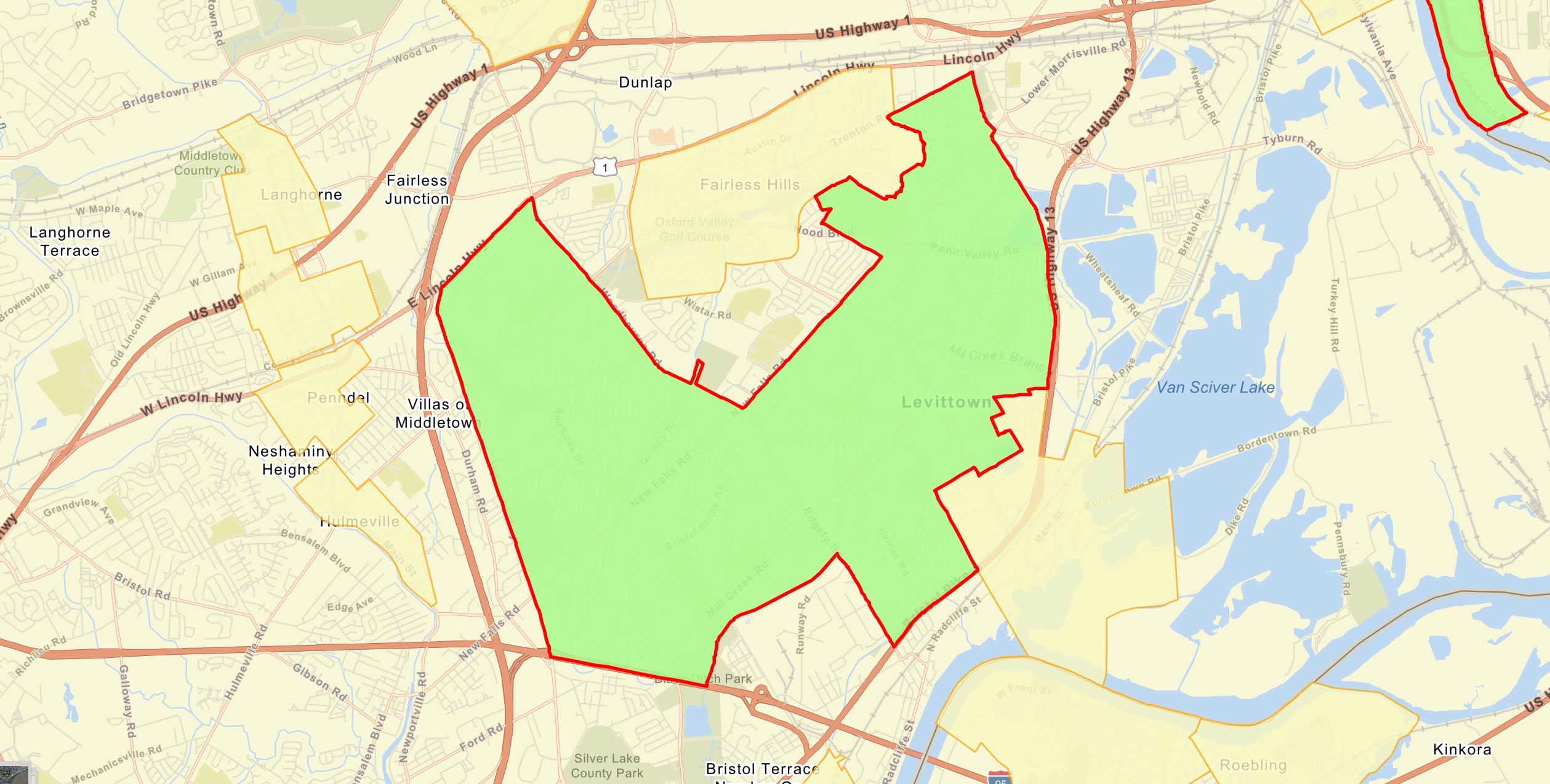

While the demographics of Levittown also reflect the history of its construction, with a homogenous, middle-class white core of occupants, they are much different than those of present-day Trenton. Although larger in area, occupying 10.4 square miles, the population of Levittown is much smaller than Trenton, with only 51,000 calling the town home. Of these residents, only 14% are considered low income, with the average per capital income coming out to around $36,219. Only 19% of the population are people of color and 87% of residents own their home. [34] These demographic trends, including the percentage of owner-occupied housing, can be seen below in the graphics provided by the EJScreen website.

Fig. 3 can be found at United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2023 version. EJScreen. Retrieved: March 16, 2024, from www.epa.gov/ejscreen.

Although the composition of these demographic profiles may not seem noteworthy at first glance, the prevalence of low income, people of color living in rental properties, as is the case in Trenton, has been commonly connected to an increased risk for lead exposure and poisoning. As noted by Eisenberg, in rental units, much more prevalent in Trenton than Levittown, “safety is largely determined by [the] landlord’s willingness and capacity to control lead hazards.” According to this same study, conducted on Detroit’s single-family rental market, the burden of lead heavily placed on urban African Americans “is a function of segregated housing markets, which constrain[s] residential mobility and restrict[s] low-income residents and people of color to older, lower-quality housing.”[35] Similar trends were found in a study of lead contamination in New York City, where it was discovered that “lead poisoning followed an income gradient with multiple disproportionate effects on non-White children in redlined neighborhoods.”

To be clear, lead contamination was found in higher numbers of children of color not because they were hereditarily predisposed, but “because the above ethnic groups live in areas where substandard housing prevails.”[36] Trenton has all of these characteristics associated with lead exposure, with a history of redlining and current demographics that are increasingly made up of low income, people of color living in rental units. Considering these factors and comparing them to Levittown, a suburban community chiefly composed of white, middle-class homeowners, Trenton’s lead woes come as less of a surprise than initially thought.

Conclusion

While the Levittown home that Amy Zalot lives in retains the tranquility that was so beloved by Russ Gambino, her place of work, Grant Intermediate, continues to face grave problems felt by the city of Trenton as a whole. The children and teachers who work at the school take their health into their hands every day that they walk into the building. Although the playground is now shut down and children do not have as much of an opportunity to track lead ridden dirt inside, the EPA has refused to take swift action on rectifying the problem in a more permanent manner. Contrarily, Amy notes that she thinks “that this plan is a short-term Band-Aid on the bigger problem” and “that the EPA and district just want this [situation] to be forgotten about.”[37]While there was some coverage of this crisis on the news, the notion that the EPA wants it to be forgotten acts as a microcosm, representative of the lead problem that plagues Trenton as a whole. Many Trentonians are affected by lead every day, whether that be through industrial exposure, lead pipes, or most commonly, chipping lead paint. In fact, according to Isles Inc., “about 50% of children in Trenton schools [like Grant] have a level of lead in their blood that affects their learning and behavior.”[38] Despite this frequent exposure and the breadth of this problem, the causes and effects of this environmental danger continue to be overlooked by the city.

Nevertheless, Trenton is not the only entity to blame in its struggle with lead contamination, as its connected history with nearby Levittown has contributed greatly to this costly environmental inequality. Before Levittown was constructed Trenton was a bustling industrial city. However, with the racially restrictive development of neighboring Levittown, many white Trentonians flocked to the new suburb, leaving African American tenants behind, having to fight for the little housing made available to people of color. With this change in population, due to the presence of redlining and racist loan policies, Trenton was changed economically and demographically. These changes stayed with the city and its population continued to become increasingly poor and composed of people of color. With this change came more rental housing, which under the watch of sometimes careless or overwhelmed landlords, routinely fell into disrepair. One of the most dangerous aspects of this lack of care manifests itself in chipping paint, which in houses built prior to the 1970s, most likely contains dangerous lead. While Levittown houses, those which changed the makeup of Trenton, were also built before the 1970s, they are mostly occupied by homeowners who have the means to properly maintain their homes. This disparity, caused by the housing policies of the 1950s, can now be seen in the disproportionate rates of childhood lead poisoning in Trenton as compared to those in Levittown.

While this injustice is deeply rooted in the histories of Trenton and Levittown and is a systemic inequality that is difficult to dismantle, groups like Isles Inc. have been working throughout the community in an effort to rectify the mistakes of the past. As expressed on their website, Isles “believes that significant change in child and family health can come from taking a comprehensive approach and focusing on the health and risks linked to housing.” In order to turn these beliefs into action, Isles has remediated over 450 homes to be lead-safe, successfully advocated for the Lead Safe Certificate Bill to become law in New Jersey, and offered Mercer County residents “free lead and healthy homes assessments” and “healthy homes kits.” [39] The work done by Isles shows that while lead is a problem in Trenton, it is one worth taking the time to deal with. If a smaller local organization like Isles, can make such a big difference in their community, why can the EPA not follow suit?

Although the response of the EPA to such a serious situation may seem surprising, the lack of care given to urban communities of color has been rather consistent throughout American history. While the time of Levittown’s construction, referred to by The American Yawp as the “affluent society,” was known to have “unrivaled prosperity alongside persistent poverty, expanded opportunity alongside entrenched discrimination, and new liberating lifestyles alongside a stifling conformity,” this dichotomy bled into more than a person’s general lifestyle and into their health and safety.[40] This inequality, furthered by publications like the Cerrell Report, which identified poor communities of color as those who would present the least resistance to sites of toxicity like garbage incinerators, is present in cities across the nation.[41] Although lead was not placed purposefully in Trenton, the cause of this lead contamination stems from government funded discrimination. Like Trenton, lead has been a monumental problem in Newark and the Oranges in North Jersey, as well as the highly publicized city of Flint, Michigan.[42] Detroit and New York City, two sites of research on housing inequity and lead exposure themselves, also face the real effects of dilapidated housing stocks leading to increased lead contamination.[43] The plight of Trenton, as caused by Levittown, should be taken seriously as a small scale example of a wide-spread, national lead problem, affecting many poor, urban communities of color disproportionately.

Endnotes:

[1] Entire first paragraph based on an interview included in: Chad M. Kimmel, “Chapter 2: Revealing the History of Levittown, One Voice at a Time,” essay, in Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh University Press, 2010), 17–40, 23-25.

[2] Gabriella Zalot and Amy Zalot, personal, April 15, 2024, based on an email interview.

[3]National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Environmental Health Science and Practice, “1970s – 1980s CLPPP Timeline,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 6, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/about/1980s.html#:~:text=The%20Lead%2DBased%20Paint%20Poisoning,“elevated%20blood%20lead%20level”.

[4] See these sources for more information on Trenton: John O. Raum, History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey: Embracing a Period of Nearly Two Hundred Years (Trenton, NJ: W.T. Nicholson & Co., Printers, 1871), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pst.000004363415 ., The Trenton Historical Society, “A History of Trenton 1679 – 1929,” Trenton Historical Society, accessed April 19, 2024, https://trentonhistory.org/trenton-history/a-history-of-trenton-1679-1929/., Isles Inc, “Lead and Healthy Homes,” Isles, Inc., June 23, 2023, https://isles.org/our-approach/live-green-and-healthy/lead-and-healthy-homes/., etc.

[5] See these sources for more information on Levittown: Dianne Suzette Harris, Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010)., Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1987)., etc

[6]Alexa Eisenberg et al., “Toxic Structures: Speculation and Lead Exposure in Detroit’s Single-Family Rental Market,” Health & Place 64 (July 2020): 102390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102390. and Robert J. Karp, “Redlining and Lead Poisoning: Causes and Consequences,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 34, no. 1 (February 2023): 431–46, https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2023.0028.

[7] https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pst.000004363415 ., The Trenton Historical Society, “A History of Trenton 1679 – 1929,” Trenton Historical Society, accessed April 19, 2024, https://trentonhistory.org/trenton-history/a-history-of-trenton-1679-1929/.

[8] John O. Raum, History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey: Embracing a Period of Nearly Two Hundred Years (Trenton, NJ: W.T. Nicholson & Co., Printers, 1871), 360.

[9] Angelica Stern, “This Week in History: The Making of the Trenton Makes Bridge,” TrentonDaily, April 6, 2023, https://www.trentondaily.com/this-week-in-history-the-making-of-the-trenton-makes-bridge/.

[10] Explanation of Levittown house types and sections come from my own personal experience growing up in the community.

[11] Dianne Harris, “‘The House I Live In’ Architecture, Modernism, and Identity in Levittown,” essay, in Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh, Pa: Pittsburgh University Press, 2010), 200–242, 202.

[12] Luther P. Jackson, “Neighbor’s Boom Worries Trenton,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[13] U.S. Census Bureau, “Number of Inhabitants: New Jersey,” 1950., can be found at: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1950/population-volume-2/23024255v2p30ch1.pdf, page 30-10.

[14] Howard G. Brunsman, “The Eighteenth Decennial Census of the United Cites: Census of Population: 1960,” 1960., can be found at: https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/edisontownship1960.pdf, pages 32-34 and 32-31.

[15] 1953 – Location Was An Important Decision In The Planning Of The Fairless Works Video, POND5 (retrofootage ), accessed April 24, 2024, https://www.pond5.com/stock-footage/item/79560534-1953-location-was-important-decision-planning-fairless-works, 1:06-1:08.

[16] Luther P. Jackson, “Neighbor’s Boom Worries Trenton,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[17]Luther P. Jackson, “Neighbor’s Boom Worries Trenton,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library Archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[18] New Jersey Department of Health, “Childhood Lead Exposure In New Jersey Annual Report” (Trenton: New Jersey, June 30, 2019), 7.

[19] Pennsylvania Department of Health, “2014 Childhood Lead Surveillance Annual Report” (Pennsylvania, April 6, 2015), 47.

[20]Alexa Eisenberg et al., “Toxic Structures: Speculation and Lead Exposure in Detroit’s Single-Family Rental Market,” Health & Place 64 (July 2020): 102390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102390.

[21] Isles Inc., “Lead and Healthy Homes,” Isles, Inc., June 23, 2023, https://isles.org/our-approach/live-green-and-healthy/lead-and-healthy-homes/.

[22] “Shelley v. Kraemer,” Oyez, accessed May 5, 2024, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/334us1.

[23] Kenneth T. Jackson, “How Washington Changed the American Housing Market,” essay, in Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 196–205.

[24]“Ike Opposed to Bias in U.S. Housing,” The Plaindealer, January 29, 1954, 56 edition, sec. 5, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A12ACD7C7734164EC%40EANX-12C8B5FEFB8AC858%402434772-12C8B5FF09AA80A8%400-12C8B5FF37F418C0%40Ike%2BOpposed%2Bto%2BBias%2Bin%2BU.%2BS.%2BHousing%2BPlans%2Bto%2BHalt%2BJim%2BCrow%2Bin%2BFederal%2BHousing%2BAired.

[25] Luther P. Jackson, “Trenton’s Negroes Short on Housing,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[26] U.S. Census Bureau, “Number of Inhabitants: New Jersey,” 1950., can be found at: https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1950/population-volume-2/23024255v2p30ch1.pdf, page 30-10. And Howard G. Brunsman, “The Eighteenth Decennial Census of the United Cites: Census of Population: 1960,” 1960., can be found at: https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/edisontownship1960.pdf, pages 32-34 and 32-31.

[27]Evelyn Gonzalez, “Trenton, New Jersey,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, February 21, 2022, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/trenton-new-jersey/#:~:text=Many%20African%20Americans%20migrated%20to,just%20when%20jobs%20were%20disappearing.

[28] Luther P. Jackson, “Trenton’s Negroes Short on Housing,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library Archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[29] Crystal Galyean, “The Imperfect Rise of the American Suburbs,” US History Scene, December 21, 2019, https://ushistoryscene.com/article/levittown/.

[30] Luther P. Jackson, “‘Perfect Planning’ at Levittown, Pa,” January 24, 1954., found in the Newark Library Archives, Clippings, Trenton 1954 folder.

[31]“Defy Mob to Live in Levittown,” The Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1957.

[32] “Inquirer Anniversary: Civil-Rights Standoff in Levittown,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 2009, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/news/local/20090803_Civil-rights_standoff_in_Levittown.html#loaded and Crisis in Levittown, PA (New York: Dynamic Films, 1957), https://www.c-span.org/video/?478354-1/crisis-levittown-pa.

[33]EPA, “EJScreen Map Descriptions,” EPA, January 3, 2024, https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/ejscreen-map-descriptions#poll.

[34] Numbers concerning Trenton and Levittown’s demographics may be found by mapping off each community using the tools found at: United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2023 version. EJScreen. Retrieved: March 16, 2024, from www.epa.gov/ejscreen.

[35] Alexa Eisenberg et al., “Toxic Structures: Speculation and Lead Exposure in Detroit’s Single-Family Rental Market,” Health & Place 64 (July 2020): 102390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102390.

[36]Robert J. Karp, “Redlining and Lead Poisoning: Causes and Consequences,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 34, no. 1 (February 2023): 431–46, https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2023.0028.

[37] Gabriella Zalot and Amy Zalot, personal, April 15, 2024., based on an email interview.

[38] Isles Inc., “Lead and Healthy Homes,” Isles, Inc., June 23, 2023, https://isles.org/our-approach/live-green-and-healthy/lead-and-healthy-homes/.

[39] Ibid.

[40]Joseph L. Locke and Ben Wright, eds., “The Affluent Society,” essay, in The American Yawp (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 288–313, 291.

[41]Luke W. Cole and Sheila R. Foster, “We Speak for Ourselves: The Struggle of Kettleman City,” essay, in From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2000), 1–9, 3.

[42]New Jersey Department of Health, “Childhood Lead Exposure In New Jersey Annual Report” (Trenton: New Jersey, June 30, 2019), 7.

[43] Alexa Eisenberg et al., “Toxic Structures: Speculation and Lead Exposure in Detroit’s Single-Family Rental Market,” Health & Place 64 (July 2020): 102390, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102390 and Robert J. Karp, “Redlining and Lead Poisoning: Causes and Consequences,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 34, no. 1 (February 2023): 431–46, https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2023.0028.

h Care for the Poor and Underserved 34, no. 1 (February 2023): 431–46, https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2023.0028.

Primary Sources:

Title: Crisis in Levittown, Pa; directed by Lester Becker and Lee R. Bobker; released January 31, 1957

Link:https://www.c-span.org/video/?478354-1/crisis-levittown-pa

Location: C-Span American History TV

Description: This source, a short documentary full of interviews, will highlight the attitudes of Levittown residents towards African Americans and further emphasize the racially exclusionary practices of the town. A large part of my argument, the impact of redlining practices, remains front and center in these interviews as many residents cite the deterioration of property value as a central reason they are wary of African American families moving into the neighborhood.

Title: RENT Housing Profiles: Trenton Housing Profile; Written by Maulin Mehta, Zoe Baldwin, Ellis Calvin, Amy Cunniff, and Leah Robinson; Published January 2023

Location: Regional Plan Association Reports

Description: This report, released by the Regional Plan Association, has a section specifically dedicated to the type of housing available in Trenton, noting that 51 percent of Trenton’s housing is occupied by renters, the median income of these renters is about half that of the home owning residents, and the fact that 86.8 percent of Trenton’s housing stock was built before 1970. While there are other supporting statistics in this document, these in particular are pivotal for underscoring the relevance of the argument that residents in Trenton are highly affected by the lead based paint in their homes because the majority are living in old, rented properties overseen by landlords that do not take the necessary steps to keep their tenants safe. This document will be used in conjunction with others that highlight the role of the Trenton landlords in these situations.

Title: Lead in Trenton Schools is Old News and a Problem that Needs Serious Action; Written by L.A. Parker for the Trentonian; published February 4, 2024

Location: Trentonian website

Description: This Trentonian article gives a voice to community action group Isles, who asserts that children are poisoned by lead through paint dust 80 percent of the time and underscores the notion that much of the damage is being done in rental properties that are rarely ever screened for lead. Taken in conjunction with my source on the makeup of Trenton’s housing stock and the sheer lack of news stories describing any lead related problems in Levittown, this source’s characterization of lead in Trenton as “old news” is useful to my argument that despite Trenton’s clear struggle with lead, not much has been done to stop it from affecting future generations of residents.

Title: Plans to Halt Jim Crow in Federal Housing Aired; Edited by James A. Hamlet Jr. at the Plaindealer of Kansas City, Kansas (Associated Negro Press News); Published on January 29, 1954

Location: Newsbank Readex database

Description: This newspaper article describes a meeting between President Eisenhower and members of the NAACP, where the main points of contention were the exclusion of African Americans from Levittown and the ways in which this discrimination not only fueled shortages of housing and job opportunities for African Americans, but was also heavily subsidized by the Federal Government. Along with my newspaper source detailing the negative connection between Levittown and Trenton, this source strengthens my argument that the federally subsidized loan practices fueling Levittown’s growth created economic and housing problems that would harm minority groups in Trenton and ultimately lead the two communities to be treated quite differently down the line in regards to their environmental status.

Title: Neighbor’s Boom Worries Trenton, Trenton’s Negroes Short on Housing, U.S. Steel Blamed For Discrimination, ‘Perfect Planning’ At Levittown, Pa. (all four articles published together to discuss the effects of the development of Levittown on Trenton); Written by Luther P. Jackson, Published January 24, 1954

Location: Newark Public Library Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center

Analysis: This series of four articles, published in 1954 by journalist and civil rights advocate Luther P. Jackson, discusses the impact that the Fairless Hills Steel Mill and the construction of Levittown had on residents of Trenton, especially those who were black. The first of these articles notes the economic impact that the new steel mill, along with the new development, will have on Trenton, noting the loss of many residents as a main point of concern. Jackson then asserts in the next article that the discriminatory practices of the Levittown community will contribute to Trenton’s shortage of housing for its black residents. Although it is noted that black Trentonians make enough to afford their own housing, the lack of viable options has caused a shortage and problem throughout the city. The next article illustrates the complicity of the federal government in creating the exclusionary Levittown community, while also pointing to U.S. steel as a source of discrimination. Finally, Jackson ends his discussion by including the voices of Levittown residents, with some accepting the racial homogeneity of the community and others, especially the Quakers, rejecting it. Although touted as a model suburb, Levittown, Pennsylvania was founded and federally funded on racist ideals that further exacerbated both the economic struggles and black housing crisis in nearby Trenton.

The federal funding of this project is primarily discussed by Jackson in the third article when he asserts that between the two, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and Veterans’ Affairs (VA) “have underwritten 98 per cent of the homes at the ‘all white’ Levittown, Pa,” even quoting a spokesperson from the FHA who announced that they “were not empowered to withhold insurance from any builder as long as his investment [was] economically sound.” Comparatively, he notes in the second article that the FHA was only in the works of funding a paltry 325 units for minorities in the area as opposed to the over 17,000 homes for white residents, highlighting their disinterest in pouring as much money into the housing of these communities. Additionally, Jackson stresses the negative economic impact that Levittown had on Trenton when he states that “Trenton [had] absorbed many of Bucks County’s headaches without sharing in its prosperity.” Here, Jackson acknowledges that Trenton was not receiving the boost in tax revenue that they predicted from the Fairless Hills Steel Mill. Instead, these more affluent white residents moved to Levittown, but a growing number of African Americans remained in crowded Trenton. According to Jackson, a central reason that Trenton was so negatively impacted was the shift of 1,482 registered voters from Mercer County to Bucks county. Despite the exodus of white residents to Levittown, Trenton was left to grapple with already crowded black neighborhoods. As asserted by City Counsel Louis Josephson, “the shortage [was] so acute that in one house in South Trenton Negroes [were] ‘sleeping in closets’.” With white tenants moving out of the city into federally funded Levittown and black residents being left behind in crowded, unkempt sections of the city, Trenton’s problems only became more prominent with the construction of “perfectly planned” Levittown.

Secondary Sources:

Harris, Dianne, ed. Second Suburb: Levittown, Pennsylvania. Pittsburg, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010. J.ctt83jhq9.2

This source is a book that combines a section of personal essays, a chapter of photographs, and a section of chapters providing historical analysis and background about the development of Levittown, Pa. Not only does this source provide background information on the construction and makeup of Levittown, but it has a specific chapter that details the struggles of integration within the town. This chapter will be of the utmost importance as I describe why black residents of Trenton could not follow their white counterparts into the Pennsylvania suburb. It also links the ways that the federal government, through programs like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), originally subsidized developments like Levittown, New York and supported their racial covenants. Even as these racial barriers were deemed unconstitutional in the case Shelley v. Kraemer, the Levitts continued to market their communities as open to whites only. Detailing the racial policies of the Levitts and the ensuing racial unrest in the community, this chapter will allow me to make the connection between Levittown’s staggering whiteness and minority Trentonians’ inability to move across the river, to a town that would eventually be much less affected by lead contamination. Compared to my other sources regarding the connection between Levittown and the federal government, this source provides a much more specific look into the makeup and ideals held by Levittown and its developers.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass frontier : the suburbanization of the United States. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985. https://primo.njit.edu/permalink/01NJIT_INST/dcbe8h/alma995290778205196.

Overall, this book examines the rise of the suburbs, from the home of the elites, to the proving ground of middle class status. While the book as a whole provides useful background information that can be used to contextualize the rise of Levittown, my focus with this source will be to analyze the chapter that explains how federal programs worked, especially as they refer to redlining. The practice of redlining, established through the HOLC practice of predicting where loans would be stable, often labeled minority districts as being risky and undeveloped and therefore marked with the Fourth Grade, red marking. As these mapping techniques gained traction, FHA programs adopted them, pulling middle class residents out of cities and placing them in more attractive suburbs. This background knowledge of these programs and the development of suburbs overall will add to my discussion of Trenton’s inability to keep hold of its middle class residents and Levittown’s ability to lure them across the river.

Karp, Robert J. “Redlining and Lead Poisoning: Causes and Consequences.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 34, no. 1 (02, 2023): 431-446. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2023.0028. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fredlining-lead-poisoning-causes-consequences%2Fdocview%2F2811705259%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

This source is a journal article that links practices of redlining to increased levels of lead contamination. According to the article, low-income children of color were at much greater risk of inflated lead levels. While the causes of lead in redlined neighborhoods were set in motion before the redlining maps were created, the lack of prevention and clean up in these undervalued communities is what now leads children in these communities to have higher blood lead levels. I will use this source in my discussion of the lead contamination that is much more prevalent in Trenton than Levittown today. Although the causes of lead contamination, like the use of lead based paint and the neglected remnants of industrial plants, were present in Trenton before the HOLC maps or Levittown’s construction, the lack of care and resources poured back into the undervalued Trenton community has led to a greater rate of lead contamination today. In addition to the connection between redlining and lead contamination, this piece also describes different policies that have been enacted over the years to try to remedy the presence of lead. If the right policies were implemented in these highly affected areas, it seems that many more lives could have been saved. The discussion of policy can be used to describe why Trenton has struggled with the problem of lead and what can possibly be done in the future to mitigate this issue.

Kumar, Nitish., and Amrit Kumar. Jha, eds. Lead Toxicity: Challenges and Solution. 1st ed. 2023. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023..https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37327-5

This source is a book that examines both the effects and possible remedies of lead pollution. When discussing the effects of lead, the book reveals that lead can cause developmental delays, learning difficulties, hyperactivity, irritability, and seizures in children. Additionally, lead exposure can make adults experience headaches, memory loss, confusion, fatigue, and depression. This book also describes the sources of lead exposure, which include contaminated soil, household dust, drinking water, and lead-glazed pottery. I will utilize this section to emphasize why lead exposure in Trenton is so dangerous and significant. In order to explain why this research is worthwhile, I will need to describe the terrible health effects that are associated with environmental lead exposure. Additionally, I will focus on the way that lead induced cognitive impairment in children can lead to poor performance in school, a key factor involved in the cycle of poverty. This cycle of poverty is a central element discussed in the connection between redlined neighborhoods and lead exposure, an important piece of my overall argument.

Raum, John O. History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey: Embracing a Period of Nearly Two Hundred Years. Trenton, NJ: W.T. Nicholson & Co., Printers, 1871. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t56d6ht7s

This is a book that covers the history of Trenton, NJ from 1676 to 1871. It highlights the development of the city from its founding, noting the great industrial potential of the community. Walking through the early history of Trenton, the book examines the community’s first government, the ways that the population of Trenton changed over time, the city’s religious and cultural institutions, and the main sources of industry. This source will lay the groundwork for my analysis of Trenton’s changing demographic and economic fortunes. Acknowledging the early history of the city and the ways in which industry shaped its development will allow me to have solid grounding of what Trenton was known for prior to deindustrialization and ensuing demographic shifts. While the development of Levittown is more contemporary, the history of Trenton is necessary to be able to make comparisons of how the city was perceived before and after the population changes seen with the construction of neighboring suburbs like Levittown. Additionally, this book covers the incorporation of multiple pottery companies, an industry whose lead contamination continues to be a problem in Trenton’s soil. Identifying the specific companies that contaminated the city will be a key aspect of examining the ways that lead affects Trenton residents today.

Image Analysis:

Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. Crowd protests African-American family from moving into Levittown (1957). Temple Digital Collections. Temple University. Accessed 2024. https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll3/id/4481.

Although many residents of Levittown, Pennsylvania, both past and present, have attempted to block out the horrific, racist events of 1957 when the Myers, the first African American family, moved into Dogwood Hollow, photographs like the one above have kept the true history alive. Retrieved from the Temple University Special Collections Research Center, this picture was first published by the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1957, with the title, Crowd Protests African-American Family From Moving Into Levittown (1).The image depicts James Newell, executive director of the Levittown Betterment Committee, towering above the rest of the crowd with a paper megaphone in hand (2). This agglomeration of men, women, and children have gathered on Haines Road, across from the Dogwood section of Levittown, in an attempt to “discuss” their next steps in protest of the Myers’ moving in.

Levittown, Trenton’s point of comparison in this project, was a pivotal factor in altering Trenton’s economic prospects and racial makeup, primarily because Levittown offered federally backed mortgages to white Americans, like James Newell, while excluding black families like the Myers. As discussed in more detail elsewhere, Trenton’s housing stock for minority tenants was quite inadequate and only exacerbated by nearby Levittown’s racial housing policies (3). Overall, this image illustrates the fact that Levittown residents not only viewed the presence of black families as a threat to their traditional, homogenous way of life, but also believed that through protests their concerns would be heard and the “correct” order of things would be restored.

One of the key indicators that these Levittown residents believed that they would successfully dispel the Myers family without much pushback, is the abundance of smiles throughout the crowd. The figures in the photograph appear to be happy and confident, seemingly not worried about the potential for any police force being used. One man sporting glasses, with his head facing directly towards the camera, is one of the most striking examples of a comfortable and positive demeanor. With the viewer’s eye drawn to the man quickly after examining the focal point, James Newell, his smile and relaxed posture suggest that he is at ease and pleased with how the event has been progressing. The woman standing to his right, also facing the camera, adds to this perception of positive energy with her noticeable grin. Typically, protesters are characterized as those who angrily oppose the system, fighting vigorously to make change. However, in this instance the protesters themselves appear to be quite unfazed, as if they know that with a little resistance, the homogenous, traditional order will be reestablished.

Another aspect of the photo that adds to the seeming confidence of the protesters is the presence of children. Although strewn throughout the sea of people, one child, resting on their father’s shoulder, draws the viewer’s eye right below the towering Newell. The presence of this child, along with others throughout the crowd, suggests that the parents in attendance feel that a racist protest, intended to move a black family out of their neighborhood, is not only a safe place for the children, but morally appropriate for them as well. Presumably, if the parents felt threatened they would not bring their children to attend the protest, highlighting their sense of safety at the event. Additionally, the parents most likely felt that the racist ideals being acted on in this photograph were at worst benign, and at best important lessons to teach their children. This ostensible sense that what they are protesting for is morally right, should be passed down, and will not be opposed by much force, illustrates the culture of Levittown at the time and the values that had been instilled through the Levitts’ racially restrictive housing policies.

Finally, the homogenous nature of the group portrayed in the photograph emphasizes the culture of conformity and the great uniformity that Levittown is known for. Most importantly, everyone pictured is white, emphasizing the racial nature of the issue. They are also dressed similarly, with many wearing plain white shirts. Many of the men are also seen sporting similar clean cut hairstyles. There is also a lack of women in the crowd, with only a few seen throughout the entire frame. This dearth of female participants suggests that many of the women may still have been at home, adhering to the rigid duties that women were responsible for as a part of the traditional nuclear family. Although the traditional Levittown family in many sense, with a working father and a handful of children, the Myers family did not quite fit into this mold that is exhibited in the picture, simply because they were black. Despite their comfort in the legitimacy of their beliefs, this group of Levittowners was seemingly threatened by the presence of a family who could potentially tarnish the homogenous makeup of their community.

The racial exclusion in the Levittown community in the 1950s and 60s, as illustrated by this image, was a key factor in the deteriorating condition of cross-river neighbor, Trenton. With the housing of African Americans already becoming a problem in Trenton, the construction of a well-made suburb across the bridge seemed to be a beacon of hope. However, the racially restrictive policies implemented by the Levitts and backed by Federal Housing Authority (FHA) loans and the mapping procedures of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), only exacerbated the problem (4). This photograph of Levittowners protesting the arrival of the first black family, full of smiling faces and children in tow, illustrates how widely accepted this racial exclusion was at the time.

Not confined to just the stories of Levittown and Trenton, the percentage of Americans who lived in suburban communities, like Levittown, grew from a mere 19.5% in 1940, to 30.7% in 1960 (5). In conjunction with the inability for minority families to move into these communities due to a reliance on redlining maps and discriminatory loan practices, they continued to be restricted to crowded, often environmentally compromised, cities. Sadly, this trend was not confined to the 1950s and 60s, and instead has a longstanding legacy. This legacy of unequal housing stock and quality continues today, where in places like Trenton, subpar housing, often occupied by renters and controlled by inattentive landlords, has an elevated likelihood of containing untreated toxic substances like lead paint (6). Despite also being built prior to the regulation of lead paint, more financially stable, white communities like Levittown are less likely to experience such environmental hazards. While these environmental inequalities are not directly caused by housing policies and racist sentiments of the past, the systems that these programs and attitudes produced perpetuate disparate environmental outcomes today.

Footnotes:

- Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Crowd Protests African-American Family from Moving into Levittown (1957), Temple Digital Collections (Temple University), accessed 2024, https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll3/id/4481

- Philadelphia Inquirer, “Civil Rights Standoff in Levittown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1957, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/news/local/20090803_Civil-rights_standoff_in_Levittown.html#loaded.

- Accessed at the Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center at the Newark Public Library: Luther P. Jackson, “Trenton’s Negroes Short on Housing,” January 24, 1954

- Accessed at the Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center at the Newark Public Library: Luther P. Jackson, “U.S. Steel Blamed for Discrimination,” January 24, 1954.

- Joseph L. Locke and Ben Wright, eds., “The Affluent Society,” essay, in The American Yawp (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019), 288–313, 291.

- L.A. Parker, “Lead in Trenton Schools Is Old News and a Problem That Needs Serious Action,” The Trentonian, February 8, 2024,https://www.trentonian.com/2024/02/08/lead-in-trenton-schools-is-old-news-and-a-problem-that-needs-serious-action-l-a-parker-colmn/.

Data Analysis:

City Boundaries of Trenton, NJ

Oral Interviews:

There are no oral interviews for this project.

Video Story:

There is no vidoe story for this project.