“They Have Forgotten About Us!”: Injustices brought onto the national spotlight due to a “natural disaster” to Ponce & San Juan, Puerto Rico

by John Wesley Crespo

Site Description:

My research is focused on two locations: the capital city of San Juan as well as the southern city of Ponce in Puerto Rico. Specifically, I am examining the various injustices that the people of San Juan and Ponce have been dealing with. The time period of my study is from pre-Maria (2010-2016) to post-Maria (October 3, 2017-present). The historical actors involved in this examination will include government officials in Puerto Rico as well as those in the mainland United States to finally the people living in these communities. Similarly, the commonwealth’s origins in regards to United States and Puerto Rican relations will be examined in providing of historical context for the environmental injustices that are evaluated.

Final Report:

Living in the United States, one’s citizenship is taken very seriously in the minds of the populous, where there are constant reminders all over that encompasses the sentiment that being a “true American” comes with the same rights and privileges as everyone else. However, most hearing this sentiment likely attribute to those living in any of the 50 states in the union and not automatically think of them living in a commonwealth of the United States, even though they too are American citizens. When we take that sip of water from the faucet or revel in the comfort provided by electricity in our homes, we rarely ask questions of where the water came from, its safety and potential side effects, to even where the electrical power source truly originates from ever come to mind. In doing so, one usually limits and takes for granted such questions and concerns regarding every day drinking water and the strength of electrical infrastructure to developing countries in the third world. Sadly, American citizens living in Puerto Rico are not immune to water and infrastructural problems, despite living in one of the most wealthy and developed country such as the United States in the world. In doing so, it challenges the sense of citizenship and whether or not every American citizen truly does have the same privileges or rights as everybody else, no matter the location of a state or commonwealth one is living in.

In 2017, a massive hurricane called Maria made landfall in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico on September 20th, causing massive destruction onto the island. In fact, just three days earlier leading up to its landfall, according to the National Weather Service, “within the next 24 to 30 hours and within an 18 hour period, Maria underwent rapid intensification, strengthening from a category 1 to an extremely dangerous category 5 hurricane”.[1] Maria’s devastation here notably impacted Puerto Rico and its capital of San Juan in the northern end of the island and Ponce located in the south.

One such instance was embodied in a source by the New York Times entitled “One Day in the Life of Battered Puerto Rico” in which it was a first-hand account 24 hours after Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico. The authors traveled to different towns in Puerto Rico, San Juan and Ponce included, to get the lay of the land and examine how the people coped with the tragedy, lack of vital aid, to finally trying to simply get by. One startling sentiment is depicted by Jorge Díaz Rivera, who stated “they have forgotten about us” as well as other sentiments that speaks volumes in that the treatment from United States was not reciprocated in terms of aid; not truly a ‘citizen’ like that of those residing in a state.[2] Rivera’s story and sentimentality here is one that is shared by so many Puerto Rican American citizens who underwent Maria’s wrath.

This project thus aims to shed light on multiple questions regarding environmental injustices Puerto Rican’s were facing in light of Hurricane Maria. Some of the more important questions include: How did Hurricane Maria and its destruction affect San Juan’s and Ponce’s infrastructure, electrical power grid, and individual perspective of one’s identity as a true citizen of the United States differently? What are the responsibilities of a sovereign nation that have unknowingly committed environmental injustices to citizens living in its commonwealth? The answer to these questions involving infrastructure and citizenship is that although Hurricane Maria was indicative of a “natural disaster,” it instead further galvanized and exposed the existing manmade environmental and economic inequalities Puerto Ricans were facing on the island, namely in San Juan and Ponce.

This study then will be focused on the inequalities centered on the comparison between San Juan and Ponce respectively. Notably, these injustices include the unequal funding and aid from the United States during pre/post Maria to San Juan and Ponce, unequal damage inflicted to that of the more prosperous capital, having better infrastructure, wealth and technology to that of the poorer one of Ponce to finally the role of corruption between local and state leaders in not appropriating funds to the people who desperately needed it to survive. In other words, this examination of injustices will help us understand the role of accountably regarding government officials whose sole goal is to the well-being of those they represent, “effective” emergency response to finally how one’s environment injustice influence the value of “worth” as a citizen in a commonwealth.

In order then to better understand how Maria truly impacted San Juan and Ponce, their environmental and economic inequalities will be further discussed. I will first analyze the impact of Maria on the infrastructure of San Juan and Ponce. Secondly, I will then link that damaged infrastructure to a lost sense of citizenship. And then finally, I will conclude with questions about the Puerto Rico’s future as well as lessons to be learned going forward.

Environmental and Economic Inequalities: San Juan vs. Puerto Rico

Hurricane Maria devastated many parts of Puerto Rico in 2017, leaving small towns and cities alike crumbling in its path of sheer destruction. Afterwards, many locations were scrambling for basic necessities such as food and water in order to provide the people relief they desperately needed. Prominent locations such as San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital and Ponce, a larger population that is more inland will be further analyzed in terms of their demographics and one of the more important environmental problems that is of great concern, that would be wastewater discharges. It is quite important to note the overall environmental issues affecting these two areas in conjunction with the demographic data. Understanding the relevant and provided information will help to understand the context in showing that after Maria made landfall and later left her destruction on San Juan and Puerto Rico, the importance of clean drinking water was a must for everyone. In fact, today there is an ongoing debate on water quality and potable water between that of FEMA and local accounts on the ground, where as you will later see, there appears to be misleading and misrepresented information on this matter entirely.

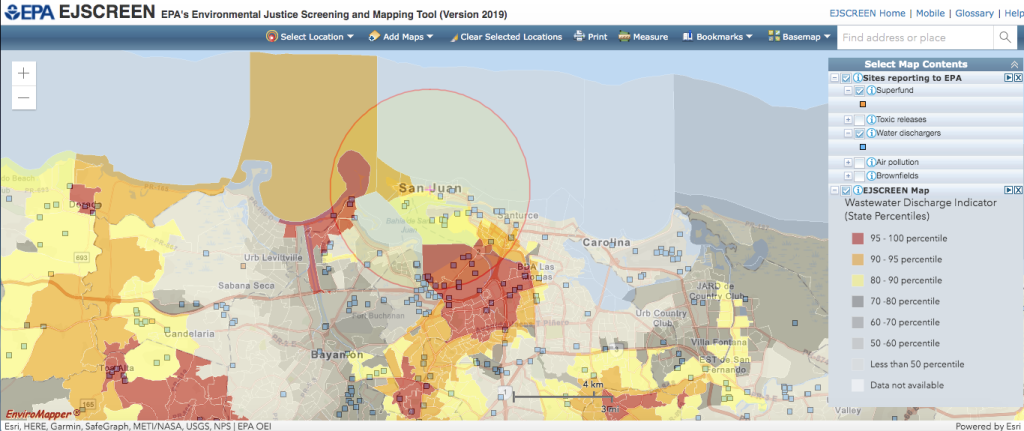

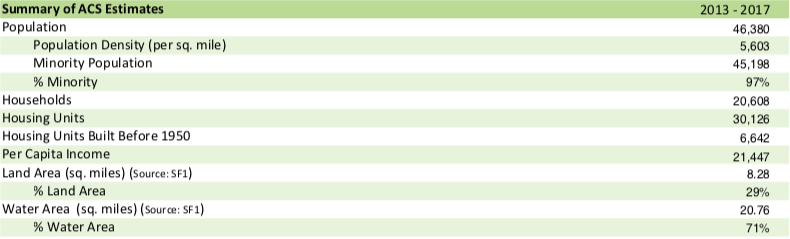

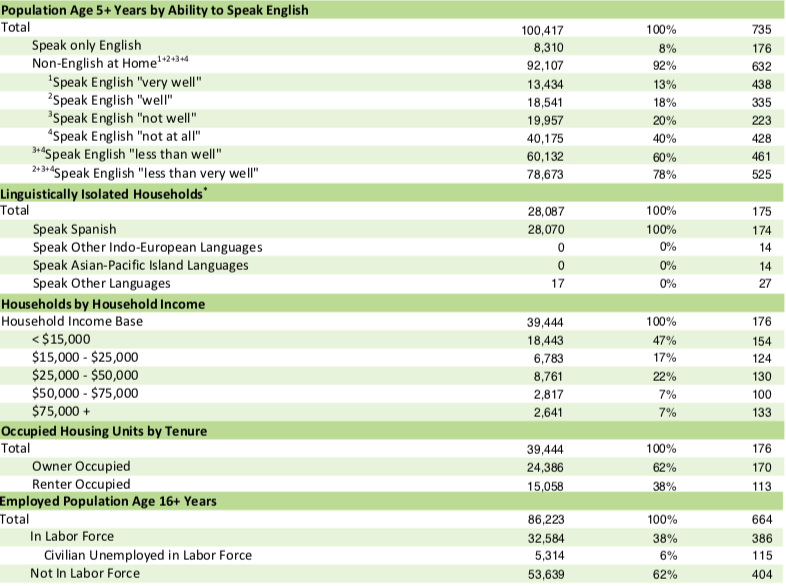

The following particular data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software, a free to use tool for any researcher or for those who simply wish to find out more about a location’s environmental issues plaguing it to their demographics. Notably, this software is able to calculate various environmental indicators and demographic statistics of one’s chosen area/site and therefore break up the data in terms of state, regional and nation-wide percentiles respectively. By inputting the location of both San Juan and Ponce and creating a 3 mile radial buffer around each city on EJSCREEN, as the images below show, we can conclude that these areas continue to experience environmental problems in relation to water, wastewater discharge where additionally based on the demographics involved in these two sites, further exuberates the notion of worth as Americans’ individual perspective of one’s identity as a true citizen of the United States.

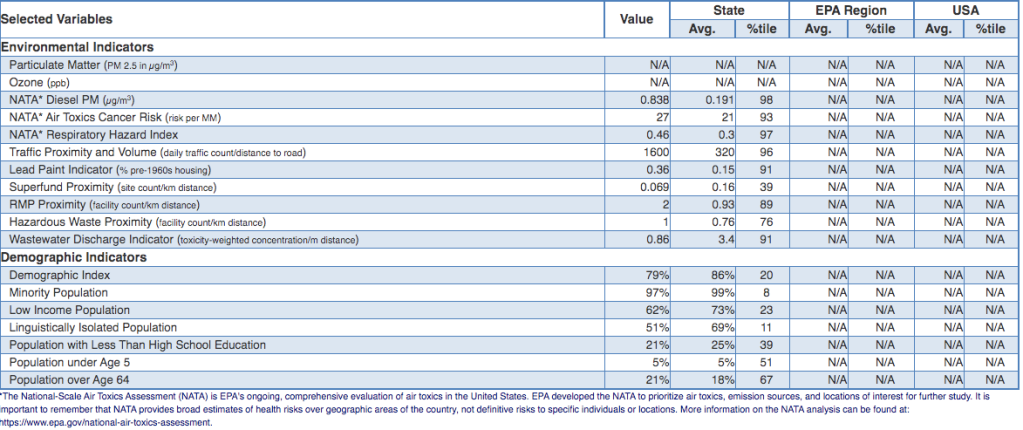

The first factor that will be analyzed is the wastewater discharge indicator (stream proximity and toxic concentration). This metric is modeled by RSEI (Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators) where the EJ Screen software calculates “Toxic Concentrations at stream segments within 500 meters, divided by distance in kilometers (km). [This is] calculated from RSEI modeled toxic concentrations to stream reach segments”.[3] In this 3 mile radial buffer zone, in San Juan and Ponce particularly, the wastewater discharge indicator (toxicity-weighted concentration/m distance) measured in 2019 is 0.86, in the 91th percentile in the state to that of Ponce’s 2.9, 95th percentile. The various data compiled by the EJSCREEN software works in the following way where this indicator is compared to that of the state percentile, what percent of the state United States “population have an equal or lower value; less potential for exposure/ risk/ proximity to certain facilities/indicators”.[4] In detail, when looking at these values for wastewater discharge indicator in that of San Juan and Ponce, only 5-9% of other locations in the state have even greater amounts of this wastewater discharge environmental issue. (See table below).

In trying to look for more data in regards to how various environmental indicators in San Juan and Ponce compare to the EPA Region and USA as a whole, there was no data to speak of that could be analyzed. In analyzing the data table that is shown above, there are a lot of “N/A” in the various environmental and demographic indicators comparing to “%tile” and “Avg” to USA, the same with EPA Region. In all truth, I thought I was doing something wrong with the software in not locating the necessary data to the various graphs that go along with the data table that for sure would be available, considering Puerto Rico is part of the United States as a commonwealth. But, as it turns out, there is no data that is provided (see blank graphs below). This stark revelation in turn illustrates environmental discrimination overall, where these American citizens are considered second class citizens in not being studied and documented by an United States federal institution, EPA compared to other respective states.

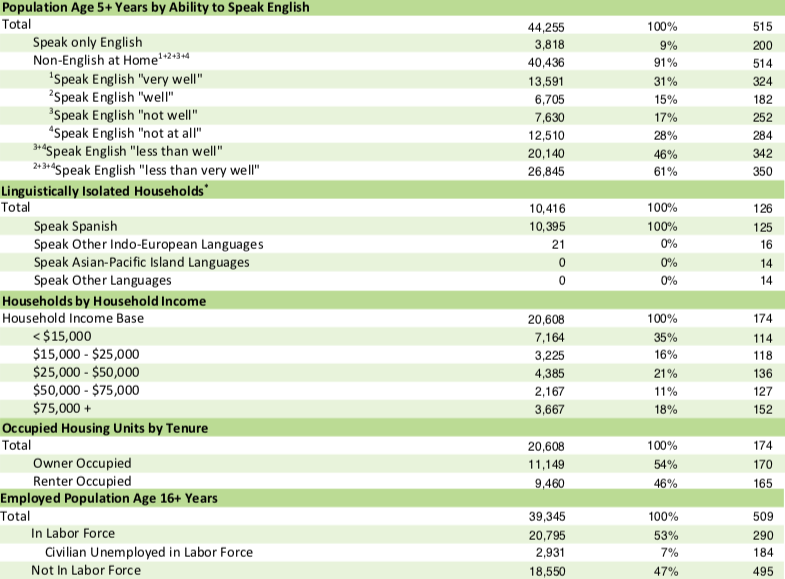

The available demographic data from 2013-2017 measured in Puerto Rico percentage and not nationally according to their respective EJSCREEN ACS Summary Reports in San Juan and Ponce show majority minority cities, comprising of 97% and 99% (see tables below). In addition to having an overwhelmingly majority minority population of American citizens in Puerto Rico, San Juan and Ponce is also home to a low-income population, with household income metric of 47% for those making less than $15,000 to that of 35% in Ponce for the amount. In fact, according to the report, San Juan has nearly half of its population over the age of 16 not in the labor force (people who are elderly, retired, etc) at 47%, whereas Ponce has a staggering 62%. What’s even more shocking is that in both San Juan and Ponce, there is still this language divide existing in a commonwealth of the United States, one of the richest and most prosperous nations on earth. According to the same report, the population of San Juan aged 5+ years old’s ability to speak English is at a shocking 91% for “Non-English at Home”, compared that to Ponce’s 92%.

This data supports the conclusion that the people in these cities, who are in their right American citizens as any other, are indeed minorities, majority of which are low-income, who are not in the labor force and suffering from a stark disadvantage of not speaking English; even though Puerto Rico is part of the United States as a commonwealth. Based on the limited environmental and demographic data from EJSCREEN, it shows that water treatment in San Juan is better than Ponce, with 0.86, in the 91th percentile in the state to that of Ponce’s 2.9, 95th percentile, where both values are still startling high in their own regards.

In addition, the ongoing debate on how truly safe the water is also a concern as FEMA suggests that 95% of Puerto Ricans are receiving potable, clean water but according to local residents and scientists on the island, this account is misleading and misrepresented. In actuality, just two months after Maria hit, residents were noticing discolored and ill-tasting water was flowing from their taps, tests showing bacterial contamination according to Puerto Rico Department of Health from the Environmental Protection Agency.[5] The notion that FEMA says Puerto Rico has potable water at its disposable is far from the truth, where contamination was widespread and according to the data above in terms of water discharges in 2019, water is still a concern in Puerto Rico, namely in San Juan and Puerto Rico seen above.

Infrastructure Vulnerabilities: Electricity

Hurricane Mara greatly affected Puerto Rico’s infrastructure, namely its electrical grid. Notably, Maria was directly responsible for the “lives of 64 people, leading to 990 excess deaths, for a total of 1054 attributable deaths, causing an estimated $90 billion in damage and destroying virtually the entire electric grid.”[6] The transmission lines in Puerto Rico were by far the most vulnerable that Maria impacted during the devastation. In fact, the “transmission lines in Puerto Rico presented important vulnerabilities. In addition of having many structures installed in difficult to access mountainous locations with thick vegetation, reports indicated that only 15 % of the lines could withstand wind forces caused by a Category 4 hurricane.”[7] As noted above, Maria was not simply a category 4 hurricane but rather a devastating category 5 storm.

Additionally, those very same lines came from electrical power plants whose location were near coastal areas; the San Juan Metropolitan Area for example as well as other coastal areas in Puerto Rico is where the majority of hotels and electric power plants are located at.[8] Along that same token, “some power plants are less than 160 feet from the waterline and less than six feet above sea level. Most businesses and other forms of economic activity are located in the coastal zone as well.”[9] All in all, the electrical grid component of San Juan and Ponce’s infrastructure here was heavily compromised.

Even before Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico’s electrical grid was quite suspect in its efficiency as well as being seen as detrimental to the island’s economic prosperity. According to a report conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy analysis on this matter titled Energy Resilience Solutions for the Puerto Rico Grid, they found that the “consensus that the high cost and low reliability of electric power in Puerto Rico is one of the most serious challenges confronting households and businesses, and a significant obstacle to economic growth on the island.”[10] A quite startling admission on the islands infrastructure pre-Maria.

The most illustrative reasons for this decline in infrastructure was analyzed and found that Maria, indicative of a “natural disaster,” challenged the foundational manmade environmental inequalities plaguing those in San Juan and Ponce. According to a report conducted by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) in 2019, they found that Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure grade of an “F” was due to “poor existing conditions, insufficient capacity and redundancy, inadequate restoration following 2017 hurricanes, poor maintenance and investment strategies, and a need for system-wide improvements. The lack of a reliable energy infrastructure today is greatly impacting human life and commerce, contributing to continued economic hardship and ever-growing financial crisis.”[11] In fact, the isolated nature of Puerto Rico’s electrical power system means that the island does not have an external support, in the likelihood of “major power disruptions.”[12] The hurricane here thus constituted as a “major power disruption”, where the economic hardship and impacting of human life as noted previously, was in part due to this devastation and the crumbling infrastructure.

In examining these faults, the notion of “human complicity” should not be disregarded but rather be a central component of these inequalities. As Ted Steinberg, Associate Professor of History and Law at Case Western Reserve University alludes to below, just because something is “natural” and it affects the populous negatively, there are elements that help to bring about these inequalities and thus must be exposed. Steinberg states that “the goal is to expose human complicity in these phenomena by looking closely at the making of high risk environments… the role that natural processes play in explaining Florida’s vulnerability to hurricane disaster must not be overlooked.”[13] As it relates to Maria and Puerto Rico, “Puerto Rico’s failed energy infrastructure did not start with the 2017 hurricanes; the existing grid was already in disrepair and experienced frequent outages. Coupled with the 2017 events, the electric grid reached the point of total failure.”[14] The human complicity and high risk environments thus were evident due to Maria helping to bring about these economic and manmade environmental inequalities.

An Image Says it all: A Symbolic Prelude to Citizenship

The image below depicts Puerto Ricans waiting in line for clean drinking water just four days after Hurricane Maria made landfall. This particular photograph is a good demonstration for my environmental justice project because it shows Puerto Ricans grappling with the failure of logistical distribution of resources on the island as well as the notion of true citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment during this time of great crisis.

Hurricane Maria first made landfall on Wednesday, September 20, 2017. Throughout the devastation of the storm, people on the island were simply trying to survive and make it to the next day, as the infrastructure began to crumble day by day. This particular photograph of American citizens in Puerto Rico waiting in line to pick up water and other vital resources with their facial expressions, body posture, and infrastructure failing at such an alarming fashion demonstrates a sense of being left alone, without official guidance and direction in their plight to get much needed resources from a governmental agency. Furthermore, this picture sheds light on the disregarded aspect entirely on the behalf of Puerto Ricans, also at the same time being American citizens, where a sense of ‘abandonment’ is exhibited to not truly being “citizens” in terms of worth as Americans due to Maria’s destruction on the island.

The photograph was taken by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times which was included in the article entitled “FEMA Was Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says” written by Frances Robles on July 12, 2018. This photograph in question was meant to accompany the article in order to demonstrate the complete lack of competence in logistics, in terms of quickly distributing vital aid to those on the island; taking four whole days for this process to start rolling out. The intended audience are those who read The New York Times and are interested in understanding the situation on the ground just four days after Hurricane Maria left the area in which how could these American citizens be without these essential goods for this long. To find out more the photographer, Victor J. Blue, I went to his personal website, https://www.victorblue.com/. In the ‘about’ section, Blue describes his work and angle overall, where he takes photos that center on people. Most notably, Blue’s collection of work is “most often concerned with the legacy of armed conflict, human rights and the protection of civilian populations, and unequal outcomes resulting from policy and politics” where the last aspect is at the heart of this photograph.

Often times, Blue’s photographs are structured close up, capturing the intimate, real life moments of a person(s) being portrayed. In this case, the Puerto Rican people sustaining unequal treatment/aid from the mainland United States, where the question of ‘How was the United States’ deployment of resources in aid to those living in San Juan as well as to those living in Ponce truly a “success?’ is illustrated in this picture demonstrating a failure in deployment. Additionally, that of corruption in the local and state level on not appropriating these resources to those who need it the most is another injustice that can be extracted from his image. All in all, Blue’s pictures deals with people who often appear deep in thought or in emotion, not just with a plastered smile, as the one above is a key example of.

The contrast of spatial relationships between that of the foreground, middle ground and background demonstrates the notion of true citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment during this time of great crisis. Notably, the foreground is of a little boy, with a striped bright colored shirt, signifying lively, hopeful persona. However, his facial expression is looking away from the complex in a downward angle, arms tied behind him holding tied up empty gallons. This in fact illustrates sadness, a sense of abandonment so to speak to those in Puerto Rico from those like the greater United States responsible and sole duty is aid in a readily and effective fashion to its people as this was not so but far from it. The people, both men and women here, are standing around waiting for admittance to the FEMA station for aid and all seem to wearing the same type of casual clothing, something one would wear when on errands or on the weekend. They seem to be around the same age, middle aged adults except for the little boy in the foreground who for the most part are mature and focused on the task at hand. Their facial expressions however are that of the little boy, head down, gloom looking, one man in fact in a crouched position, head down.

The flurry of activity in the foreground of the photograph serves to starkly contrast with the lack of activity in the background of the photograph: the mountain ranges and that of wilderness. The lack of American flag or Americana in general in terms of no officials guiding, answering questions, to even comforting demeanor is present. This suggests that the leadership and that of aid as symbolized by the gray road is lacking because there is literally no leader or organizer that is present directing the distribution of the water and other vital aid. The American flag or any American iconography symbolizing the nation as one, unified entity is lacking entirely. The qualities that one associates with the flag, such as freedom, access to resources and prosperity does not match the concerned and tense atmosphere in the photo by these citizens. Thus, the notion of ‘true’ citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment of not being taken as a sense of priority during this time of great crisis is presented here with the spatial relationships and body expressions of those in the fore and middle grounds, where Blue captured well here in this photograph.

Furthermore, the people are who are present in the picture seem to be working together at an equal level, as concerned citizens, holding empty gallons, buckets, containers to be filled. However, the emptiness that exists next to the line of citizens other than that one little boy zoomed in the foreground symbolizes the lack of proper and adequate leadership, especially when dealing with the ramifications of the crisis of this magnitude. The fact that there are no displays, signs, or even governmental automobiles serving in a humanitarian capacity in this picture but rather a parking lot of cars in the background belonging to the citizens in line are examples of abandonment, disregard, touching upon this idea of “worth” as true American citizens in a commonwealth.

One of the takeaway messages that is presented here in this photograph is the lack of leadership present visually and metaphorically in this Hurricane Maria crisis where in the end, Puerto Ricans are left alone, without official guidance/direction in their plight to get much needed resources from a governmental agency, disregarded entirely. San Juan and Ponce are one of the largest cities in Puerto Rico, in one of the most prosperous nations in the entire world. Thus, this lack of access to resources as basic as clean and pure water as well as its deployment to the people, the corruption aspect that plays into it to finally the notion of “worth” as American citizens of a commonwealth paints a painful picture for the citizens of Puerto Rico in their struggle of sheer survival post Hurricane Maria.

Corruption – Why inequalities happened?

The role of corruption in Puerto Rico in the end did not help better the island’s cause for the above inequalities but rather chipped away at it and helped to bring about the notion of mistrust in the government. In fact, “This year, Puerto Rico was included on a list of 22 jurisdictions with “strategic deficiencies” in combatting money laundering and “terrorist financing,” according to the European Commission… The mobilization of corruption narratives against Puerto Ricans has systematically eroded the Island’s democratic rights and entitlements.”[15] One such prime example of corruption was government officials in Puerto Rico who were directing federal funds, whose sum is in the billions of dollars, appropriated by the United States Congress to private politicly connected contractors.[16] In turn they were profiting from these investments even before Maria; the hurricane in question rather simply exposed these six individuals after the fact.

In conjunction with corrupt government officials, FEMA’s response to Maria was ill-prepared in directing aid to the American citizens on the island, an illustrative representation of mistrust in government. According to Frances Robles article titled “FEMA Was Sorely Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says”, FEMA did just that. Robles below states that “[FEMA] took longer than expected to secure supplies and lost track of much of the aid it delivered and who needed it… The report underscores how ill-prepared the agency was to manage a crisis outside the continental United States, like the one in Puerto Rico. And it urges communities in harm’s way not to count so heavily on FEMA in a future crisis.”[17] In answering why the inequalities above happened, a prime contributor rather than a stoppage were the very same government officials whose sole responsibility should have been to their citizens but instead prioritized private interests. In doing so and not taking direct, reasonable action in these matters, the economic and environmental injustices lingered, rather than being rectified swiftly.

Conclusion: Going Forward and Citizenship

In conclusion, although Hurricane Maria was indicative of a “natural disaster,” it instead further galvanized and exposed the existing manmade environmental and economic inequalities Puerto Ricans were facing on the island, namely in San Juan and Ponce. Going forward, time will tell what will happen to the small island of Puerto Rico, whether they will break away from the United States and operate as an sovereign, independent nation or remain as a commonwealth. In light of this though, today “Puerto Rico sits politically and economically challenged by the pull of not being “developed” like the U.S. yet not being “underdeveloped” like other parts of the Caribbean and Latin America.”[18] Likewise with day-long power outages still occurring, especially in rural areas where even some homes still have tarps on roofs.[19]

The examination of both San Juan and Ponce, through its infrastructural differences, notably the state of their electrical power grid and water quality pre/post Maria truly challenges what it means to be an American citizen living in a commonwealth having the same rights, privileges and level of concern in times of crisis to that of a state. In fact, a poll conducted in 2017 through September 22-24 by Morning Consult, found that out of 2,200 adults, “only 54 percent of Americans know that people born in Puerto Rico, a commonwealth of the United States, are U.S. citizens”.[20] Even more startling was that “only 37 percent of people ages 18 to 29 know people born in Puerto Rico are citizens, compared with 64 percent of those 65 or older. Similarly, 47 percent of Americans without a college degree know Puerto Ricans are Americans, compared with 72 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree and 66 percent of those with a postgraduate education”.[21] With some of the environmental injustices mentioned above as well as with the present corruption existing on the island on behalf of the police force in municipalities and government officials, no wonder Puerto Rican’s were questioning their value of “worth” of citizenship.

At the heart of this, Puerto Rico is thus judged not only by its commonwealth status, but also through the people’s way of life as being ‘different’. Specifically, “how the embodied experience of obtaining food, water, power, and other necessities through alternate means revealed not only how Puerto Ricans are legally or politically different from residents of the mainland United States, but also how they are racialized in ways that support the ongoing dispossession and exploitation of the island.”[22] This legal and political difference that Puerto Ricans face, despite them being ‘American citizens’ as any who lives in one of the 50 states is what my grandfather Bartolo Ortiz, tried to convey. Oritz, who lived on the island for most of his life remarked in an oral interview that I conducted, which can be listened to above, that “Puerto Rico does not have the same privileges and rights because it is acommonwealth”[23] could not be more certain. In the end, it is up to the American citizens themselves on the island, through all of the injustices that has impacted them, that will decide where the future of Puerto Rico will go looking forward into the future.

Notes

[1] US Department of Commerce and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Major Hurricane Maria – September 20, 2017,” (NOAA’s National Weather Service, September 12, 2019), 1.

[2] Frances Robles et al., “One Day in the Life of Battered Puerto Rico” (The New York Times, September 30, 2017),1.

[3] “How to interpret a standard report in EJSCREEN”. EPA. April 5, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/how-interpret-standard-report-ejscreen

[4] “How to interpret a standard report in EJSCREEN”. EPA. April 5, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/how-interpret-standard-report-ejscreen

[5]Mekela Panditharatne . “FEMA says Puerto Rico has drinkable water. It doesn’t”. The Denver Post, 2017, 1.

[6] Phil Brown, Carmen M. Vélez Vega, Colleen B. Murphy, Michael Welton, Hector Torres, Zaira Rosario, Akram Alshawabkeh, José F. Cordero, Ingrid Y. Padilla, and John D. Meeker. “Hurricanes and the Environmental Justice Island: Irma and Maria in Puerto Rico”. Environmental Justice. Aug 2018. 150, Accessed: April 30, 2020, http://doi.org/10.1089/env.2018.0003

[7] Alexis Kwasinski et al., “Hurricane Maria Effects on Puerto Rico Electric Power Infrastructure,” IEEE Power and Energy Technology Systems Journal 6, no. 1 (2019): p. 89, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jpets.2019.2900293)

[8] Kasey R Jacobs and Ernesto L Diaz, “Working Group 3 Report Climate Change and Puerto Rico’s Society and Economy,” Society and Economy, n.d., 254.

[9] Kasey R Jacobs and Ernesto L Diaz, “Working Group 3 Report Climate Change and Puerto Rico’s Society and Economy,” Society and Economy, n.d., 254.

[10] U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Resilience Solutions for the Puerto Rico Grid. June 2018, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/06/f53/DOE%20Report_Energy%20Resilience%20Solutions%20for%20the%20PR%20Grid%20Final%20June%202018.pdf

[11]“Report Card for Puerto Rico’s Infrastructure”, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), 2019, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-Puerto-Rico-Report-Card-Final.pdf

[12] Efraín O’neill-Carrillo, and Miguel A. Rivera-Quiñones. 2018. “Energy Policies in Puerto Rico and Their Impact on the Likelihood of a Resilient and Sustainable Electric Power Infrastructure.” Centro Journal 30 (3): 150, Accessed: April 30, 2020, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=136081828&site=ehost-live.

[13] Theodore Steinberg. “Do-It-Yourself Deathscape: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in South Florida.” Environmental History 2, no. 4 (1997): 415. Accessed April 30, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3985607.

[14] “Puerto Rico Earns a ‘D-” in ASCE Infrastructure Report Card”, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), November 12, 2019, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://www.asce.org/templates/press-release-detail.aspx?id=34226)

[15] Joaquín Villanueva, “Corruption Narratives and Colonial Technologies in Puerto Rico,” NACLA Report on the Americas 51, no. 2 (March 2019): p. 188, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2019.1617489)

[16] Jeff Stein, “FBI Makes Arrests in Puerto Rico Corruption Scandal, Prompting Calls for Governor’s Ouster and Concerns about Billions in Storm Aid,” The Washington Post, July 11, 2019, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/07/10/fbi-makes-arrests-puerto-rico-corruption-scandal-prompting-calls-governors-ouster-concerns-about-billions-storm-aid/)

[17] Frances Robles, “FEMA Was Sorely Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says,” The New York Times, July 12, 2018, Accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/12/us/fema-puerto-rico-maria.html)

[18] Zaire Flores, “The Development Paradox”, NACLA Report on the Americas 50, bo.2 (2018): 167, Accessed: April 30, 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2018.1479479)

[19] “The Facts: Hurricane Maria’s Effect on Puerto Rico”, Mercy Corps, January 8, 2020, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/quick-facts-hurricane-maria-puerto-rico?source=SF3WUMSTZMNZZ9999991)

[20] Kyle Dropp and Brendan Nyhan, “Nearly Half of Americans Don’t Know Puerto Ricans Are Fellow Citizens” (The New York Times, September 26, 2017), 1.

[21] Kyle Dropp and Brendan Nyhan, “Nearly Half of Americans Don’t Know Puerto Ricans Are Fellow Citizens” (The New York Times, September 26, 2017),1.

[22]Rosa E. Ficek, “Infrastructure and Colonial Difference in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María,” Transforming Anthropology 26, no. 2 (2018): p. 103, Accessed: April 30, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12129)

[23]Bartolo Ortiz, interview by John Crespo, April 14, 2020.

Primary Sources:

Source 1

Robles, Frances, Luis Ferré-sadurní, Richard Fausset, and Ivelisse Rivera. “One Day in the Life of Battered Puerto Rico.” The New York Times, September 30, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/30/us/24-hours-in-puerto-rico-after-hurricane-maria.html

This source by the New York Times is a first-hand account 24 hours after Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico. The writers above traveled to different towns in Puerto Rico, San Juan and Ponce included, to get the lay of the land and examine how the people coped with the tragedy, lack of vital aid, to finally trying to simply get by. I will be using this source in my paper to demonstrate the value of ‘worth’ as a citizen, how Puerto Rican’s mentality differed greatly in this regard compared with state vs. commonwealth and lacking infrastructure. One such example is a quote that stuck out to me from Jorge Díaz Rivera who stated “they have forgotten about us” as well as other sentiments that speaks volumes in that the treatment from United States was not reciprocated in terms of aid; not truly a ‘citizen’ like that of a state but rather a commonwealth. Additionally, the infrastructure aspect of my paper post Hurricane Maria will also be briefly examined where condition of roads and houses were severely damaged, first-hand accounts are provided throughout; will be great to incorporate a sense of “realism” in my paper so that the reader can easily comprehend in invoking emotion while reading. All in all, I believe this primary source will be quite useful and impactful in my paper due to the first-hand accounts, vivid imagery, as well as touching upon some of the aspects I am focusing on.

Source 2

U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Resilience Solutions for the Puerto Rico Grid. June 2018. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/06/f53/DOE%20Report_Energy%20Resilience%20Solutions%20for%20the%20PR%20Grid%20Final%20June%202018.pdf

This government document by the U.S. Department of Energy examined the energy/infrastructural system of Puerto Rico pre Hurricane Maria as well as providing recommendations to the improvement of such systems post-Maria. I will be using this document in my paper to demonstrate how the energy infrastructure of Puerto Rico pre-Maria was already lacking, as this document shows the various ways in which the failing system operated. One key example is detailed in one of the main sections in this report dubbed “The Pre-Storm Condition of the Electricity System” where it goes into more depth in the specifics; for instance poor management of power plants is critically looked at. There are graphs and figures in this report that serve as great eye openers in just how lacking Puerto Rico’s energy/infrastructural system really was, where Hurricane Maria truly set back this system decades. Overall, this primary source is a great example detailing Puerto Rico’s lacking energy system pre/post Maria, where the two factors include the high cost and finally low reliability to its people; an aspect I will examine wholeheartedly in my paper.

Source 3

Stein, Jeff. “FBI Makes Arrests in Puerto Rico Corruption Scandal, Prompting Calls for Governor’s Ouster and Concerns about Billions in Storm Aid.” The Washington Post. WP Company, July 11, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/07/10/fbi-makes-arrests-puerto-rico-corruption-scandal-prompting-calls-governors-ouster-concerns-about-billions-storm-aid/.

This source is important as it examines the corruption scandal that was going on pre Hurricane Maria to even after it made landfall. Specifically, government officials in Puerto Rico were directing federal funds, whose sum is in the billions of dollars, appropriated by the United States Congress to private politicly connected contractors. In turn they were profiting from these investments even before Maria; the hurricane in question rather simply exposed these 6 individuals after the fact. I plan to use this source in my paper to speak about the aspect of corruption in Puerto Rico, notably its capital of San Juan where these government officials posts were located at, where Hurricane Maria greatly brought onto the national spotlight these illegal acts. In doing so, I plan on answering the question regarding ‘How did corruption at both the local and state level further bring on environmental injustices to those in San Juan and Ponce?’ in that the people could not have received vital aid in a fast timeframe due to illegal direction of federal funds to private entities rather than to their people themselves they supposed to represent. This source in the end is a good example of corruption that was going on in the time frame I am looking at (2010-2017) that unfortunately further galvanized environmental injustices for Puerto Ricans even after Maria made landfall.

Secondary Sources:

Ficek, Rosa E. 2018. “Infrastructure and Colonial Difference in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María.” Transforming Anthropology 26 (2): 102–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12129.

This secondary source is an academic, peer-reviewed journal article from Transforming Anthropology that describes the infrastructural and colonial differences post Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Ficek goes into great depth on the ‘everyday’ struggles Puerto Ricans were facing weeks after Maria made landfall, examining the various strategies they used to obtain vital resources, despite the weak infrastructure that existed pre Maria to the then current shattered one that presided. Furthermore, this source explores the idea of “worth” as a citizen in a commonwealth, where the ‘racialization’ of Puerto Ricans as colonial citizens was embodied as Ficek puts it due to these experiences of acquiring food, water, power in Maria’s aftermath. Ficek’s article thus will help to understand and conceptualize the colonial differences in Puerto Rico as well as the deteriorating infrastructure pre/post Maria. Additionally, this source will be used in my paper to discuss this inequality of ‘worth’ as a citizen of the United States living in a commonwealth and not in a state where Maria further brought out this notion overall.

O’neill-Carrillo, Efraín, and Miguel A. Rivera-Quiñones. 2018. “Energy Policies in Puerto Rico and Their Impact on the Likelihood of a Resilient and Sustainable Electric Power Infrastructure.” Centro Journal 30 (3): 147–71. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=136081828&site=ehost-live.

This secondary source is an academic, peer-reviewed journal article from Centro Journal that examines Puerto Rico’s electrical power infrastructure—notably, how Hurricane Maria uncovered various flaws and fatalities in the dated fossil based generation system used in towns like that in Ponce. The damage that presided was catastrophic all over the island but as the authors above point out, the electrical power gird as well as the energy policies that existed in San Juan varied greatly to the rest of the island, like that of Ponce in the southern section of the island. This source then will be used in my paper to discuss in comparison the infrastructural aspect of environmental injustice attributable to better technology and electrical power system policies in San Juan to that of the lesser technological and weaker systems in Ponce. Furthermore, this source will offer an insight on how this stark contrast came to fruition pre Hurricane Maria to finally being brought onto the national spotlight due these systems being heavily affected after the fact.

Villanueva, Joaquín. 2019. “Corruption Narratives and Colonial Technologies in Puerto Rico: How a Long-Term View of U.S Colonialism in Puerto Rico Reveals the Contradictory ‘Political Work’ of Corruption Discourse, Both in Extending Colonial Rule and in Resisting It.” NACLA Report on the Americas. Vol. 51. doi:10.1080/10714839.2019.1617489.

This secondary source is an academic, peer-reviewed journal article from NACLA Report on the Americas that examines corruption in Puerto Rico, notably from 2010 – 2017, just shortly after Hurricane Maria made landfall. Moreover, Villanueva here looks at the dichotomy between colony and corruption and how government officials from both mainland United States as well as those in Puerto Rico participated in various illegal activities, negatively affecting residents in San Juan and Ponce. In fact, the U.S. Congress in 2016 signed into law the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) to combat just this issue of corruption committed by Puerto Rican government officials. This law in turn appoints an oversight board called ‘La Junta’, to regulate and manage Puerto Rico’s finances; a “babysitter” action as Villanueva eloquently refers to it. Overall, this source will be used in my paper to address the political/corruption aspect of environmental injustice affecting those in San Juan and Puerto Rico and how due to Hurricane Maria, this issue was brought to the national spotlight in dissecting where the money was funneled to and how this was so.

Image Analysis:

The image chosen for my image analysis assignment is a photograph of Puerto Ricans waiting in line for clean drinking water just four days after Hurricane Maria made landfall. This particular photograph is a good demonstration for my environmental justice project because it shows Puerto Ricans grappling with the failure of logistical distribution of resources on the island as well as the notion of true citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment during this time of great crisis. Hurricane Maria first made landfall on Wednesday, September 20, 2017. Throughout the devastation of the storm, people on the island were simply trying to survive and make it to the next day, as the infrastructure began to crumble day by day. This particular photograph of American citizens in Puerto Rico waiting in line to pick up water and other vital resources with their facial expressions, body posture, and infrastructure failing at such an alarming fashion demonstrates a sense of being left alone, without official guidance/direction in their plight to get much needed resources from a governmental agency. Furthermore, this picture sheds light on the disregarded aspect entirely on the behalf of Puerto Ricans, also at the same time being American citizens, where a sense of ‘abandonment’ is exhibited to not truly being “citizens” in terms of worth as Americans due to Maria’s destruction on the island.

The photograph was taken by Victor J. Blue for The New York Times which was included in the article entitled “FEMA Was Unprepared for Puerto Rico Hurricane, Report Says” written by Frances Robles on July 12, 2018. This photograph in question was meant to accompany the article in order to demonstrate the complete lack of competence in logistics, in terms of quickly distributing vital aid to those on the island; taking four whole days for this process to start rolling out. The intended audience are those who read The New York Times and are interested in understanding the situation on the ground just four days after Hurricane Maria left the area in which how could these American citizens be without these essential goods for this long. To find out more the photographer, Victor J. Blue, I went to his personal website, https://www.victorblue.com/. In the ‘about’ section, Blue describes his work and angle overall, where he takes photos that center on people. Most notably, Blue’s collection of work is “most often concerned with the legacy of armed conflict, human rights and the protection of civilian populations, and unequal outcomes resulting from policy and politics” where the last aspect is at the heart of this photograph.

Often times, Blue’s photographs are structured close up, capturing the intimate, real life moments of a person(s) being portrayed. In this case, the Puerto Rican people sustaining unequal treatment/aid from the mainland United States, where the question of ‘How was the United States’ deployment of resources in aid to those living in San Juan as well as to those living in Ponce truly a “success?’ is illustrated in this picture demonstrating a failure in deployment. Additionally, that of corruption in the local and state level on not appropriating these resources to those who need it the most is another injustice that can be extracted from his image. All in all, Blue’s pictures deals with people who often appear deep in thought or in emotion, not just with a plastered smile, as the one above is a key example of.

The main color that is apparent and continuously present in this picture is a dark gray. Specifically, the main road of asphalt/gravel these people are standing on, waiting to receive water and other vital goods from FEMA taking place in a police station just four days after Maria impacted the island. The color of gray sadly, represents dire times, death, negative emotions overall, which is most significant because the issue on the minds of these citizens is that of negative emotions, perilous circumstances that have befallen onto them due to no fault of their own. The color of gray can also represent the institution itself, in this case FEMA and that of police, where this road indeed leads into the complex that holds this aid, presided by state and local officials whereas the dirt road next to it is brown colored, signifying Puerto Rico in of itself; its innocent citizens. In essence, this clash/intersection of colors between dark shade of gray and that of brown illustrates the dichotomy of world between FEMA, officials, and police to that of the innocent citizens. Clothing color on the people here is bright for the most part (orange, red, blue, pink, yellow, and white), illustrating hope and lively persona of its wearers in terms of great crisis in getting relief. Thus, this clash of colors consisting of brown vs. gray demonstrates corruption in the local and state level on not appropriating these resources to those who needs it in a timely, well executed manner, where the “police” here fits that of gray color road leading into the station and who have been responsible in various corruption scandals on the island intersecting that of the dirt brown road next to it. In the end however, it has been four whole days after Maria left and Puerto Ricans has not even received basic aid (water) further shows this incompetence to even corruption like in holding back these resources of aid as well as lack in effective deployment in its totality.

The contrast of spatial relationships between that of the foreground, middle ground and background demonstrates the notion of true citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment during this time of great crisis. Notably, the foreground is of a little boy, with a striped bright colored shirt, signifying lively, hopeful persona. However, his facial expression is looking away from the complex in a downward angle, arms tied behind him holding tied up empty gallons. This in fact illustrates sadness, a sense of abandonment so to speak to those in Puerto Rico from those like the greater United States responsible and sole duty is aid in a readily and effective fashion to its people as this was not so but far from it. The people, both men and women here, are standing around waiting for admittance to the FEMA station for aid and all seem to wearing the same type of casual clothing, something one would wear when on errands or on the weekend. They see to be around the same age, middle aged adults except for the little boy in the foreground who for the most part are mature and focused on the task at hand. Their facial expressions however are that of the little boy, head down, gloom looking, one man in fact in a crouched position, head down.

The flurry of activity in the foreground of the photograph serves to starkly contrast with the lack of activity in the background of the photograph: the mountain ranges and that of wilderness. The lack of American flag or Americana in general in terms of no officials guiding, answering questions, to even comforting demeanor is present. This suggests that the leadership and that of aid as symbolized by the gray road is lacking because there is literally no leader or organizer that is present directing the distribution of the water and other vital aid. The American flag or any American iconography symbolizing the nation as one, unified entity is lacking entirely. The qualities that one associates with the flag, such as freedom, access to resources and prosperity does not match the concerned and tense atmosphere in the photo by these citizens. Thus, the notion of ‘true’ citizenship and value of worth as American citizens of a commonwealth illustrating disregard and abandonment of not being taken as a sense of priority during this time of great crisis is presented here with the spatial relationships and body expressions of those in the fore and middle grounds, where Blue captured well here in this photograph.

Furthermore, the people are who are present in the picture seem to be working together at an equal level, as concerned citizens, holding empty gallons, buckets, containers to be filled. However, the emptiness that exists next to the line of citizens other than that one little boy zoomed in the foreground symbolizes the lack of proper and adequate leadership, especially when dealing with the ramifications of the crisis of this magnitude. The fact that there are no displays, signs, or even governmental automobiles serving in a humanitarian capacity in this picture but rather a parking lot of cars in the background belonging to the citizens in line are examples of abandonment, disregard, touching upon this idea of “worth” as true American citizens in a commonwealth.

One of the takeaway messages that is presented here in this photograph is the lack of leadership present visually and metaphorically in this Hurricane Maria crisis where in the end, Puerto Ricans are left alone, without official guidance/direction in their plight to get much needed resources from a governmental agency, disregarded entirely. San Juan and Ponce are one of the largest cities in Puerto Rico, in one of the most prosperous nations in the entire world. Thus, this lack of access to resources as basic as clean and pure water as well as its deployment to the people, the corruption aspect that plays into it to finally the notion of “worth” as American citizens of a commonwealth paints a painful picture for the citizens of Puerto Rico in their struggle of sheer survival post Hurricane Maria.

Data Analysis:

Hurricane Maria devastated many parts of Puerto Rico in 2017, leaving small towns and cities alike crumbling in its path of sheer destruction. Afterwards, many locations were scrambling for basic necessities such as food and water in order to provide the people relief they desperately needed. Prominent locations such as San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital, and Ponce, a town that is more inland, will be further analyzed in terms of their demographics and one of the more important environmental problems that is of great concern, that would be wastewater discharges. It is quite important to note the overall environmental issues affecting these two areas in conjunction with the demographic data. Understanding the relevant and provided information will help to understand the context in showing that after Maria made landfall and later left her destruction on San Juan and Puerto Rico, the importance of clean drinking water was a must for everyone. In fact, today there is an ongoing debate on water quality and potable water between that of FEMA and local accounts on the ground, where as you will later see, there appears to be misleading and misrepresented information on this matter entirely.

The following particular data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software, a free to use tool for any researcher or for those who simply wish to find out more about a location’s environmental issues and connecting them to its demographics. Notably, this software is able to calculate various environmental indicators and demographic statistics of one’s chosen area/site and therefore break up the data in terms of state, regional and nation-wide percentiles respectively. By inputting the location of both San Juan and Ponce and creating a 3 mile radial buffer around each city on EJSCREEN, as the images above show, we can conclude that these areas continue to experience environmental problems in relation to water, specifically wastewater discharge.

The first factor that will be analyzed is the wastewater discharge indicator (stream proximity and toxic concentration). This metric is modeled by RSEI (Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators) where the EJ Screen software calculates “Toxic Concentrations at stream segments within 500 meters, divided by distance in kilometers (km). [This is] calculated from RSEI modeled toxic concentrations to stream reach segments”.[1] In this 3 mile radial buffer zone, in San Juan and Ponce particularly, the wastewater discharge indicator (toxicity-weighted concentration/m distance) measured in 2019 is 0.86, in the 91th percentile in the state to that of Ponce’s 2.9, 95th percentile. The various data compiled by the EJSCREEN software works in the following way where this indicator is compared to that of the state percentile, what percent of the state United States “population have an equal or lower value; less potential for exposure/risk/proximity to certain facilities/indicators”.[2]In detail, when looking at these values for wastewater discharge indicator in that of San Juan and Ponce, only 5-9% of other locations in the state have even greater amounts of this wastewater discharge environmental issue.

In trying to look for more data in regards to how various environmental indicators in San Juan and Ponce compare to the EPA Region and USA as a whole, there was no data that could be analyzed. In analyzing the data table that is shown above, there are a lot of “N/A” in the various environmental and demographic indicators comparing to “%tile” and “Avg” to USA, the same with EPA Region. When navigating to the section “Explore Reports”, there are no graphs shown that would compare environmental indicators and demographics to USA percentile and regional percentile (see figure 4&5). In all truth, I thought I was doing something wrong with the software in not locating the necessary data to the various graphs that go along with the data table that for sure would be available, considering Puerto Rico is part of the United States as a commonwealth. But, as it turns out, there is no data provided. This stark revelation in turn illustrates environmental discrimination overall, where these American citizens are considered second class citizens in not being studied and documented by an United States federal institution, EPA compared to other respective states.

The available demographic data from 2013-2017 measured in Puerto Rico percentage and not nationally according to their respective EJSCREEN ACS Summary Reports in San Juan and Ponce show majority minority cities, comprising of 97% and 99%. In addition to having an overwhelmingly majority minority population of American citizens in Puerto Rico, San Juan and Ponce are also home to a low-income population, with a household income metric of 47% for those making less than $15,000 to that of 35% in Ponce for the amount. In fact, according to the report, San Juan has nearly half of its population over the age of 16 not in the labor force (people who are elderly, retired, etc) at 47%, whereas Ponce has a staggering 62%. What’s even more shocking is that in both San Juan and Ponce, there is still this language divide existing in a commonwealth of the United States, one of the richest and most prosperous nations on earth. According to the same report, the population of San Juan aged 5+ years old’s ability to speak English is at a shocking 91% for “Non-English at Home”, compared that to Ponce’s 92%.

Thusly, this data supports the conclusion that the people in these cities, who are in their right American citizens as any other, are indeed minorities, majority of which are low-income, who are not in the labor force and suffering from a stark disadvantage of not speaking English; even though Puerto Rico is part of the United States as a commonwealth. Based on the limited environmental and demographic data from EJSCREEN, it shows that water treatment in San Juan is better than Ponce, with 0.86, in the 91th percentile in the state to that of Ponce’s 2.9, 95th percentile, where both values are still startling high in their own regards. In addition, the ongoing debate on how truly safe the water is also a concern as FEMA suggests that 95% of Puerto Ricans are receiving potable, clean water but according to local residents and scientists on the island, this account is misleading and misrepresented. In actuality, just two months after Maria hit, residents were noticing discolored and ill-tasting water was flowing from their taps, tests showing bacterial contamination according to Puerto Rico Department of Health from the Environmental Protection Agency.[3] The notion that FEMA says Puerto Rico has potable water at its disposable is far from the truth, where contamination was widespread and according to the data above in terms of water discharges in 2019, water is still a concern in Puerto Rico, namely in San Juan and Puerto Rico seen above.

[1] “Glossary of EJSCREEN Terms.” EPA. April 5, 2020.

[2] “How to interpret a standard report in EJSCREEN”. EPA. April 5, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/how-interpret-standard-report-ejscreen

[3] Panditharatne, Mekela . “FEMA says Puerto Rico has drinkable water. It doesn’t”. The Denver Post, 2017.

Oral Interviews:

I conducted an oral Interview with my grandpa, Bartolo Ortiz, who lived in Ponce for nearly 30 years and was living on the island when Hurricane Maria made landfall in Ponce, Puerto Rico in 2017. You will hear his opinions regarding the status of corruption, infrastructure and citizenship (state vs. commonwealth) in Puerto Rico during [pre/during/post] Hurricane Maria respectively.