Newark Becomes ‘Host’ to X-Files Conspiracy: The Search for Truth and Justice in the Nation’s Second Largest Sewer

by Christina Nguyen

Site Description:

The X-Files is one of the most recognizable and culturally significant television series to come out of the 1990s, influencing countless spinoffs and sparking mass public interest in “the unknown” ever since it first premiered in 1993. An early episode from 1994 (“The Host,” Season 2, Episode 2) documents the unintentional discovery of a mutant humanoid flukeworm on a Russian submarine and the accidental release of the dangerous creature into U.S. waters. The hazardous parasite begins to flex and unleash harm on human life beginning in none other than the city of Newark, New Jersey. The “Monster of the Week” is then investigated and exposed to be a product and consequence of a nuclear disaster. We will explore the City of Newark’s classic, gritty image through comparison and parallels as it is portrayed in the Flukeman’s emergence from the subterranean.

Final Report:

View a presentation on the conspiracy by clicking the link above.

Introduction

The X-Files is one of the most recognizable and culturally significant television series to come out of the 1990s, influencing countless spinoffs and sparking mass public interest in “the unknown” ever since it first premiered in 1993. An early episode from the second season in 1994, entitled “The Host,” tells the story of a humanoid flukeworm parasite, or “Monster of the Week” as scholars have categorized this literary character, and its emergence from the septic tank inside a Russian submarine two miles off of the New Jersey shore. Our villain, the “Flukeman” commits his first murder on an unsuspecting grunt crewmember who is on latrine duty aboard the vessel. Shortly thereafter, a sanitation worker is attacked by a mysterious entity underwater who turns out to be Flukeman, resurfacing at none other than the old and decrepit brick sewer tunnels of the City of Newark, New Jersey. The young man is subsequently released later that day from the hospital following receipt of a clean bill of health, only to be found dead the next day in the shower.

Through clever filmmaking and suspenseful storytelling by X-Files creator Chris Carter, the young sanitation worker’s cause of death was ruled as internal injuries due to complete, irreparable parasitic infestation of the host entity. Or in other words, for the casual viewer: Flukeman laid some eggs inside the man’s body during the submerged attack; the larvae fed on all nutritional value that it could leech from within the human host until it was time to crawl out into the world by means of esophageal emission. The Federal Bureau of Investigation is commissioned to explore both City of Newark homicide cases involving the sewage treatment employee and the unidentified Russian sailor’s bodies having been found in the decaying drainage tunnels. “The Host” concludes with the scientific discovery of Flukeman’s origins as “manmade” – a product of human experimentation and radioactive nuclear fallout.[1]

For more than a century, Newark, New Jersey has been a tarnished icon significant in its representation of urban decay, chosen as the defining location for runaway failed experiments as portrayed in the classic X-Files episode. Newark is the perfect host – literally, as an amalgamation of mankind’s corruption and indifference to the environment, and figuratively, as the perfect host as the quintessence of urban disintegration that is poignantly allegorized in its much-outdated sewer system. Due to the city’s inability to rebuild its former industrial-millionaire glory of the late-19th Century, Newark has become infamous as the archetypal symbol of urban American deterioration. The deeply rooted web of conspiracy that fuels The X-Files to investigate corruption and injustices committed by large government entities is accurately portrayed in a locally serious manner, by way of its using Newark’s 167-year-old sewage system serving as a coalescence of numerous infrastructural, social, and political problems that the City of Newark has been struggling with for decades. The inequalities surrounding the Newark sewage system’s functionality and management are the same negative forces that are collectively considered as the conspiracy surrounding Newark’s squalor.

As with any conspiracy, Newark’s ailing situation begs one to question as to how and why the city got to such a critical point. In order to shed some light on this disturbing catechism, it is perhaps helpful, and entertaining, to relate it through parallels of “The Host.” By considering the workings of the satirical Newark and its drainage network that is portrayed in The X-Files, we could obtain a better understanding of how its infamous stereotype came to be, and perhaps learn a lesson on what could be done to improve the condition of some of America’s largest cities. We will take a look at the history, mechanical and political makings of the watershed system and the corruption surrounding it, whilst making connections to its metaphorical representation in the X-Files’ Flukeman scheme. Newark’s toiled complications are a much deeper-biting parasite than what is observed on the surface.

The X-Files’ choice of the city and particularly its tainted, outdated sewer tunnels is a compelling decision on the filmmakers’ part. By conveying the narrative of a renegade, living mutant by-product wreaking homicidal havoc on such a specified, low-income, densely populated metropolitan area, the show is making a profound statement on the major problems of the target city by bringing it to the forefront of public media attention while being partially disguised as purely entertainment. Attention to detail is paid closely by The X-Files’ filmmakers, as seen in shots of the local and federal authorities investigating the Flukeman’s crime scenes underground – proper credit should be acknowledged as to the accurate depiction of the original 19th Century brick structure, 20th Century concrete renovation, as well as the open treatment pits on the ground surface. By realistically committing to their decision in story location, the film crew remains loyal to the actual goings-on of the town itself.

History and Background of the Newark Sewer System

A total estimated 3.4 million New Jersey and New York residents rely on the Newark Bay system[1]. The Newark Bay watershed and waste management network spans for approximately 22 miles in length, equating to 150 square miles of coverage across 48 municipalities in Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Union, and Passaic Counties in northern New Jersey.[2][3] It is the second-largest drainage network in the United States following Los Angeles, California and services the Passaic and Hackensack Rivers, as well as the Upper New York Bay that includes Ellis, Liberty, and Governors Island, and much of the Boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island – this massive coverage area accounts for approximately 50% of New York City’s population alone.[4]

Newark’s original underground sewer system was constructed in 1852 during the heart of the Industrial Revolution. Following the installation of the Morris Canal and two railroads, the city experienced a significant population boom as manufacturers and big business migrated to the newly convenient and economically appealing frontier. With the massive influx of industry and its workers, the present “natural” drainage system that simply consisted of dirt trenches, could no longer accommodate the rapidly-increasing volume of waste and overflow. The state-of-the-art brick system was impressive for its time. However, the issue lay in the city’s inability to construct the sufficient quantity of pipe mileage to service the entire municipality and surrounding coverage area. This substandard upkeep has remained relatively the same ever since, over a century later with the population swelling to nearly five times from that of the mid-1800s.

The Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission (PVSC) has taken over management operations for the Newark Bay and sewage system since 1902 when the agency was originally established for the purposes of overseeing the update and expansion of the original 1852 brick structure with additional concrete water lines. At the turn of the 20th Century, excess sewage and stormwater run-off was efficiently disposed of through the use of combined sewer overflows (CSOs), which were able to remove sewage quickly for the smaller volume of residential and business use at that time. Since 1902, this excess sewage is processed at the Newark Bay Treatment Plant on Wilson Avenue in the city of Newark, instead of flowing directly into the Bay, Hackensack, or Passaic River. Although the installation of the treatment plant appears to be beneficial at first glance, that is no longer the case. There has been no new expansion of the treatment facility that is able to accommodate the present-day population and volume of waste material that has inflated with time and increased consumer use, causing flooding and discharge of sewage into residential areas as well as the rivers and bays for more than one hundred years.[5]

As a result of Newark Bay’s location and function as a major port industry in combination with the tremendous volume of waste overflow pouring in from factories, coverage cities and their tributary rivers, the amount of unnatural, manmade and harmful chemicals contained in the water is staggering. In 2018, the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission issued a comprehensive 228-page Service Area System Characterization Report that documents all of the Commission’s functions. The following list contains the most harmful out of dozens of chemicals found in large quantities in Newark Bay:

All of these pollutants are widely known to cause debilitating health hazards to land and marine life that depend on the Bay as a natural resource as well as for residential and commercial use. Cancer, wildlife fatalities, and birth defects are just a few of the many harmful effects that these substances cause on a biological level. According to New Jersey Future, an independent non-profit organization whose one of several goals is to ensure the betterment of the state’s infrastructural development, 100% of the East Newark neighborhood alone is located in a CSO drainage area, meaning that its entirety is subject to flooding under raw sewage each time there is heavy rainfall.[1]

Not only is toxic waste purposely directed into the major bodies of the Newark and Upper New York Bay, it has been proven that intentional dumping occurs rampantly throughout the constructed drainage network’s 167-year history. The PVSC has been sued numerous times in both state superior and federal courts for intentionally dumping an approximate 200 million gallons of raw sewage into Newark Bay as of a 1968 civil suit filed by the State of New Jersey Department of Health with regards to the inadequate CSO system and its inability to process excess waste that the treatment facility cannot handle.[2]

Corruption and the Community’s Fight Back

The mere pollution itself is only a fraction of the major concerns surrounding Newark’s sewer system. As just briefly mentioned, the level of malpractice on the Commission’s part is already overwhelmingly devastating from that one aspect alone. In a highly-publicized crackdown on corruption in 2011, former New Jersey State Governor Chris Christie terminated the employment of 71 high-ranking PVSC employees on account of “the scandal-ridden agency.”[1] Unfortunately, the misconduct runs deeper, regarding the Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation (NWCDC) that works in conjunction with the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission as its non-profit overseer. In an official 2014 report issued by the State of New Jersey Comptroller’s Office, former agency director Linda Watkins-Brashear, was discovered to have pilfered upwards of $10 million in funds in the form of personal checks written out to herself, fellow colleagues, and political allies in Essex County.[2]

The City of Newark is not entirely without help, however. Resilient, committed, locally-run and citizen-operated organizations maintain a strong presence throughout the municipality. One of the most successful, longstanding and impactful groups is the Ironbound Community Corporation, who have fought against powerful industries such as the Covanta incinerator and Diamond Alkali (Agent Orange) factories in past decades, and triumphantly pushed for the development of Newark’s scenic Riverfront Park. The Newark Water Group, and the ICC in conjunction with Newark Stormwater Solutions have steadfastly worked to serve and improve their beautiful and culturally unique community with the backing of many surrounding towns and loyal supporters from afar.[3]

Newark in Popular Culture

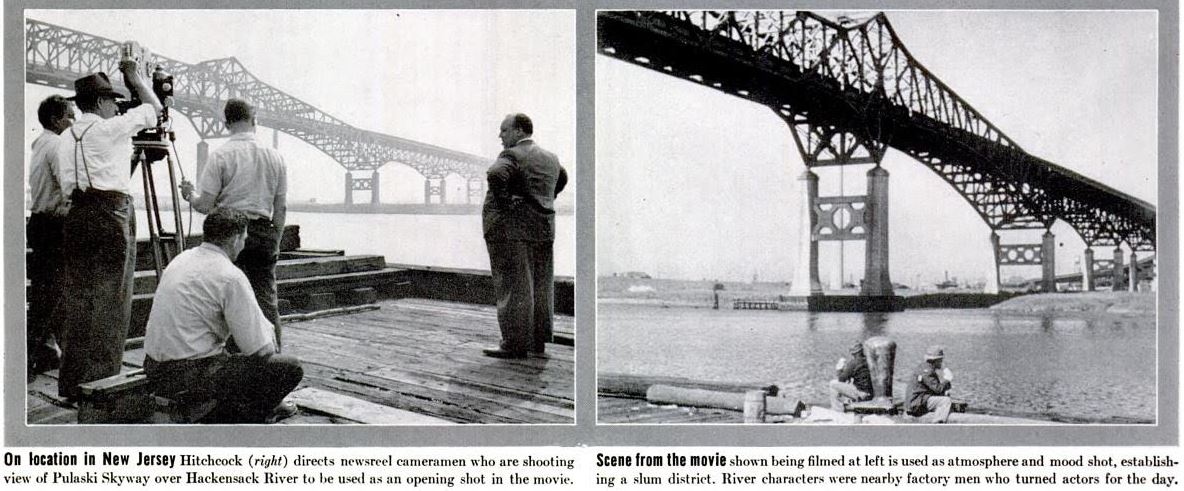

Newark’s most recognizable Hollywood cameo is pictured above in a production shot and finished movie still from Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, featured in a Life Magazine article from 1943. The photographs together feature the Pulaski Skyway looming over the Hackensack River as a backdrop for Hitchcock’s vision of [the city of Newark as] a decaying urban slum in one of the opening scenes of the film. Although subject site is the Newark Bay Treatment Plant that was selected as the basis for the 1994 X-Files episode, this image from fifty years prior of the same sewage and watershed system provides further evidence supporting the argument that Newark was and remains the classic, quintessential icon of urban deterioration, hence its use in many examples within American popular culture. With regard to such significant and staggering infrastructural problems that leave a permanent stain visually and psychologically on the City of Newark’s reputation, it is no wonder that the notorious Brick City is consistently being utilized as the filming location and background for numerous stories in American popular culture.

Hitchcock chose this particular location for the authentic, industrial feel and affordable cost as opposed to hiring a construction crew to build a complete movie set from scratch. The Pulaski Skyway, despite having been newly completed at the time, only added to the industrial feel which the filmmaker was attempting to convey as the antagonist of Shadow of a Doubt seeks refuge in a dilapidated boarding house in the nearby Ironbound neighborhood. Local factory workers from the area were recruited as extras portraying homeless men in the newsreel-esque scene. The point of view is taken from the Newark side, as the audience’s eye moves across the bridge to Jersey City on the other side of the Hackensack River.

The idea of Newark as being the stereotypical deteriorating city has long been the standard alongside New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and other notable film noir (a popular cinematic trend ranging from the 1940s to 1960s that almost always take place in dark, grimy, and seedy urban settings) locales. To highlight and enhance the blighted atmosphere, two extras dressed in destroyed clothing are carefully placed in the forefront of the movie still, seemingly relaxed and unstressed, perhaps without prioritized obligations. The viewer could properly assume that the men are homeless and unemployed, which explains their loitering during the middle of the day instead of conducting tasks at the workplace.

The main focal point of the two photographs is the monumental and domineering General Pulaski Skyway that overlooks the scene. The position and time of day in which Hitchcock chose to film this opening sequence is interpreted from the point of view being seen from the shadowy side of the bridge, therefore draping the city in darkness. Visually it is angled in such a way that it creates an almost panoramic optical illusion to emphasize the gargantuan scope of the structure. Being seen from the literal and figurative darker side, the gloomy bridge and enormous mass now have an intimidating presence over the observer on the ground.[1]

An overlying theme of the choice of location and final photograph is the barren, unsafe and perilous nature of the scenery. One detail that the viewer may notice is the lack of recreational boats on the river. This is likely due to the fact that the Newark/Jersey City/Kearny area is a major industrial port zone and therefore does not accommodate local or residential use of the waterways. Secondly, the Pulaski Skyway has had a tumultuous and overall ineffective history since its completion in 1932, deemed as “the sixth most unreliable road in the United States” by the Texas Transportation Institute in 2011.[2] Poor design that results in countless accidents, unsafe conditions, and the inability to handle large industrial vehicles are all indications of failed infrastructure, which then in turn, further augments the undesirability of the area.

Although seemingly completely unrelated to The X-Files television series in the 1990s, this snapshot of the earlier, more primitive days of the American film industry both share a common theme: utilizing the city of Newark, New Jersey as the eternal icon of urban decay. It is clearly documented by the “Master of Suspense” Alfred Hitchcock – an English-born filmmaker whom acknowledged this idea of the city in such manner, far before X-Files creator Chris Carter’s use of the same setting fifty years later for his own story about “grimy business” going on in a degenerative inner city. The crumbling status of the city has remained relatively unchanged for the entirety of the Postwar period.

Conclusion

“We live in very interesting times, technologically, politically and socially,” series creator and head writer Chris Carter asserts.[1] The Flukeman monster emerging onto the surface and crossing paths with the above-ground world is an allegorical statement on the genuinely alarming and persistent problems that Newark has been struggling with for decades coming to a head, yearning for discourse and solution. By spotlighting Newark’s typical inner-city issues for a national audience, this strategy raises widespread awareness on not only Newark’s fallacies, but the archetypally urban social, political, and infrastructural quandaries that need to be addressed on a national scale.

The extensive political corruption and pollution are a continuing obstacle for nearly, if not all large cities in the United States and more often than not, the citizens’ pleas are silenced by the ruling entities perched on top. All of the previously listed issues in this study have reached such a crucial point in the “host” City of Newark’s timeline of existence that they manifested into the form of an artificial, synthetic monstrosity emerging from the tarnished subterranean below, gasping for air and exculpation. The predominant lesson that we all must learn from “Flukeman” is, comprehensively – the societal detriments that are addressed in “The Host” are strictly manmade, and therefore their remedies are just as equally rectifiable by mankind. As the Doctor and Special Agent Dana Scully proclaims at the end of the episode, “Nature didn’t make this thing, we did; it was born in a primordial soup of radioactive sewage.”[2]

End Notes

[1] The X-Files. Season 2, Episode 2, “The Host,” directed by Chris Carter, aired September 23, 1994, on Fox Network. Produced by 20th Century Fox Television.

[2] Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 2007. Newark Bay. October 28. https://www.fema.gov/newark-bay.

[3] Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission, 1996-2019. Who We Are. State of New Jersey. https://www.nj.gov/pvsc/who/

[4] Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. Service Area System Characterization Report (Newark: Greeley and Hansen: CDM Smith, 2018).

[5] Curtis, Drew. Interview by author. Voice recording. Newark, April 18, 2019.

[6] Sturm, Chris, and Nicholas Dickerson. 2014. Ripple Effects: The State of Water Infrastructure in New Jersey Cities and Why it Matters. New Jersey Future, 2.

[7] PVSC, Service Area System Characterization Report, 86.

[8] Sturm and Dickerson, 3.

[9] State of New Jersey Department of Health v. Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. 1968. 100 N.J. Super. 540 (1968) (Superior Court of New Jersey, Chancery Division, April 24).

[10] Sherman, Ted. “Gov. Christie Fires 71 Passaic Valley Sewerage Commissioners Employees.” NJ Advance Media, February 8, 2011.

[11] State of New Jersey, Office of the State Comptroller. 2014. “Investigative Report: Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation.” Investigative Report.

[12] Curtis, Drew

[13] Life Magazine. “$5,000 Production.” (Life Magazine, January 25, 1943), 70-78.

[14] Shadow of a Doubt. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. 1943. Produced by Skirball Productions. Universal Pictures.

[15] Wikipedia.

[16] Carter, Chris, interview by BuddyTV. The X-Files Interview with Chris Carter (December 28, 2017).

Bibliography

Carter, Chris. The X-Files Interview with Chris Carter. BuddyTV. 28 December 2017.

Curtis, Drew. Interview. Christina Nguyen. 18 April 2019.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Newark Bay. 28 October 2007. https://www.fema.gov/newark-bay.

Life Magazine. “$5,000 Production.” Life Magazine. 25 January 1943: 70-78.

Modica, Glenn. The History of the Newark Sewer System : A Project of the City of Newark, Department of Water and Sewer Utilities, Newark, New Jersey. Cranbury: Richard Grubb & Associates, Inc., 2001.

National Wildlife Federation v. Environmental Protection Agency and Sewage Authorities. No. 744 F.2d 963 (1984). United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit. 11 June 1984.

Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. Service Area System Characterization Report. Newark: Greeley and Hansen: CDM Smith, 2018.

—. State of New Jersey: Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. 1996-2019. State of New Jersey. https://www.nj.gov/pvsc/who/.

People of the State of New York v. State of New Jersey and Passaic Valley Sewerage Commissioners. No. 256 U.S. 296 (1921). Supreme Court of United States. 8 November 1918.

Shadow of a Doubt. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Skirball Productions. Universal Pictures, 1943.

Sherman, Ted. “Gov. Christie Fires 71 Passaic Valley Sewerage Commissioners Employees.” NJ Advance Media 8 February 2011.

State of New Jersey Department of Health v. Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission. No. 100 N.J. Super. 540 (1968). Superior Court of New Jersey, Chancery Division. 24 April 1968.

State of New Jersey, Office of the State Comptroller. “Investigative Report: Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation.” Investigative Report. 2014.

Sturm, Chris and Nicholas Dickerson. Ripple Effects: The State of Water Infrastructure in New Jersey Cities and Why it Matters. New Jersey Future, 2014.

The Toxic Avenger. Dirs. Lloyd Kaufman and Michael Herz. Troma Entertainment. 1984.

The X-Files. Dir. Chris Carter. 20th Century Fox Television. 1993.

Primary Sources:

The X-Files: Season 10 (comic book series), Vols. 6 & 7

Location: Available for purchase in print or e-book on Amazon, Kindle, or comiXology (an independent retailer)

The original X-Files television series aired for nine seasons, from 1993 to 2002. This comic book installment, authorized and partially written by the creator of the show, Chris Carter, was created as a continuation of the original storyline. These two volumes elaborate on the episode entitled “The Host,” providing more background and history surrounding the infamous Russian “flukeman” character and how/why the monster came to be. The original 1993 episode took place in Newark, New Jersey; some questions that often occur are: Why was Newark chosen to ‘host’ a biohazard released by a Russian submarine? Is this a satire on Newark as a quintessential, decaying urban slum? Why were the inhabitants of this particular city targeted? Reading the extended background and story of this plot will help the those interested in solving the mystery of these inquiries as well as debunk the writer’s allegorical intent of such distinctive drama.

Report on the Operations and Management of the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission by the Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce

Location: Special Collections & University Archives – Sinclair New Jersey Collection (TD525.N6G74 1983)

This is a 70-page pamphlet written in 1983 by the Greater Newark Chamber of Commerce, a community organization formed in 1924 to encourage and regulate growth and prosperity of business and industry in the city of Newark. The 1980s were a turning point for the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission (the PVSC being the agency that operates the sewage system), for a second treatment facility was constructed in order to handle higher capacity and to improve quality of water and sewage treatment. Since the additional facility was built in 1981, a report written approximately two years after the start of operation will provide detailed information on the actual quality and productivity of the second plant.[1]

[1] Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission, “History – Development and Extent of the PVSC Organization” <https://www.nj.gov/pvsc/who/history>

Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission Long Term Control Plan – Combined and Separated Sewer Systems Map

Location: Online source < https://www.nj.gov/dep/dwq/pdf/cso_sewermap_newark.pdf> < https://www.pvscsewers.com/maps>

These maps provide a look at what population of which specific towns/counties inhabit and would be affected by a biological threat if it were to be released in the Newark sewage system. As part of the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission’s coverage area, residents immediately affected by a water-borne parasite would include large parts of Essex and Passaic Counties. The icons represent currently active treatment facilities.

Secondary Sources:

Modica, Glenn. 2001. The History of the Newark Sewer System: A Project of the City of Newark, Department of Water and Sewer Utilities, Newark, New Jersey. Cranbury, NJ: Richard Grubb & Associates, Inc.

This book documents the entire history of the Newark sewer system, from its original (and now historically-recognized) brick construction in the mid-1800s, up until its usage, influence, and status up until 2001. In 1990, the city embarked on an extensive plan to upgrade. This “rehabilitation” project included revamping manhole covers and all main water lines circulating throughout the city. Modica writes in much detail of the poorly-maintained and dilapidated water utilities and their effects on residents’ lives during the 1990s. Since The X-Files aired in that same decade, this work will provide valuable background information about Newark on the local community level for purposes of decoding why this specific site was chosen to film a culturally influential television program in, and furthermore – supply evidential fact as to why the city of Newark represents the filmmakers’ idea of a decaying urban slum.

Weesh, Dr., and Vic Vega. 2018. The Host – 2X02. http://www.insidethex.co.uk/transcrp/scrp202.htm.

This is a fan-produced transcript of Episode 2 of Season 2 of The X-Files entitled “The Host,” which this project will be centering on. (Creators of the series and Fox Entertainment have not released or endorsed any official episode scripts.) In addition to citing the actual visual television episode itself, it would be helpful to have documentation of the story in written form for manual reference purposes – it is more convenient to cite text than a video recording. In the final paper, lines from this document will be cited in lieu of citing the moving images.

Whitfield, Stephen J. 1991. The Culture of the Cold War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Whitfield’s book is a detailed account of the effect that the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union had (and still has) over American life – this includes popular culture, religion, literature, the entertainment industry, patriotism and nationalism – nearly every aspect of American life. In relation to this research project, one must again refer to the question of why in the X-Files episode of “The Host” document an unaccounted-for Russian sea vessel travelling so close to U.S. waters? Furthermore, why was this vessel carrying hazardous cargo? The even broader inquiry is, why are hints of Cold War situations and conflicts so popular in American popular culture? Another direction that could be taken in this project is to answer the question as to why the city of Newark, New Jersey was chosen by an internationally syndicated television program to represent urban decay.

Image Analysis:

The chosen visuals are two connected images: a production shot and a finished movie still from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940s film Shadow of a Doubt featured in a Life Magazine article from said decade. The photographs together feature the Pulaski Skyway looming over the Hackensack River as a backdrop for Hitchcock’s vision of [the city of Newark as] a decaying urban slum in one of the opening scenes of the film. Although my chosen site is the Newark Sewage Treatment Plant that was selected as the basis for a 1993 X-Files episode, this image from fifty years prior of the same sewage and watershed system provides further evidence supporting the argument that Newark was and remains the classic, quintessential icon of urban deterioration, hence its use in many examples within American popular culture.

Alfred Hitchcock chose this particular location for the authentic industrial feel and affordable cost as opposed to hiring a construction crew to build a complete movie set from scratch. The Pulaski Skyway, despite having been newly completed at the time, only added to the industrial feel which the filmmaker was attempting to convey as the antagonist of Shadow of a Doubt seeks refuge in a dilapidated boarding house in the nearby Ironbound neighborhood. Local factory workers from the area were recruited as extras portraying homeless men in the newsreel-esque scene. The point of view is taken from the Newark side, as the audience’s eye moves across the bridge to Jersey City on the other side of the Hackensack River.

The idea of Newark as being the stereotypical deteriorating city has long been the standard alongside New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and other notable film noir (a popular cinematic trend ranging from the 1940s to 1960s that almost always take place in dark, grimy, and seedy urban settings) locales. To highlight and enhance the blighted atmosphere, two extras dressed in destroyed clothing are carefully placed in the forefront of the movie still, seemingly relaxed and unstressed, perhaps without prioritized obligations. The viewer could properly assume that the men are homeless and unemployed, which explains their loitering during the middle of the day instead of conducting tasks at the workplace.

The main focal point of the two photographs is the monumental and domineering General Pulaski Skyway that overlooks the scene. The position and time of day in which Hitchcock chose to film this opening sequence is interpreted from the point of view being seen from the shadowy side of the bridge, therefore draping the city in darkness. Visually it is angled in such a way that it creates an almost panoramic optical illusion to emphasize the gargantuan scope of the structure. Being seen from the literal and figurative darker side, the gloomy bridge and enormous mass now have an intimidating presence over the observer on the ground.

An overlying theme of the choice of location and final photograph is the barren, unsafe and perilous nature of the scenery. One detail that the viewer may notice is the lack of recreational boats on the river. This is likely due to the fact that the Newark/Jersey City/Kearny area is a major industrial port zone and therefore does not accommodate local or residential use of the waterways. Secondly, the Pulaski Skyway has had a tumultuous and overall ineffective history since its completion in 1932, deemed as “the sixth most unreliable road in the United States” by the Texas Transportation Institute in 2011[1]. Poor design that results in countless accidents, unsafe conditions, and the inability to handle large industrial vehicles are all indications of failed infrastructure, which then in turn, further augments the undesirability of the area.

Although seemingly completely unrelated to the The X-Files television series in the 1990s, this snapshot of the earlier, more primitive days of the American film industry both share a common theme: utilizing the city of Newark, New Jersey as the eternal icon of urban decay. It is clearly documented by the “Master of Suspense” Alfred Hitchcock – an English-born filmmaker whom acknowledged this idea of the city in such manner, far before X-Files creator Chris Carter’s use of the same setting fifty years later for his own story about “grimy business” going on in a degenerative inner city. The crumbling status of the city has remained relatively unchanged for the entirety of the Postwar period.

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews:

Interview with Drew Curtis, Senior Equitable Development Manager of the Ironbound Community Corporation – April 18, 2019

Video Story: