The Merchants of Trenton: Business, Recreation, and the Highway in a Postwar City

by Kyle Stegner

Site Description:

The City of Trenton – specifically parts of West Trenton and the Capital area – during the immediate postwar period holds many stories of environmental justice. The State of New Jersey, in the late 1940s and 1950s, was planning the placement and construction of an urban freeway to run along the Delaware River and cut through some of Trenton’s most precious spaces. The road went by different names – Route 29, Sanhican Drive, the East-West Highway – but many contemporaries called it the Assunpink Way, for it would run through the historically potent Assunpink Creek. Polls conducted at the time declared a majority of Trentonians supported the new freeway in order to relieve traffic congestion downtown, but some locals rejected the plans; small business owners along South Broad Street saw it as a detriment to their bottom-line, and leisurely citizens in search of green spaces were afraid it would cause the destruction of Stacy Park.

Final Report:

As the rain began to fall on the crowded Stacy Park on a cloudy May night in 1954, visitors sought shelter. Over a thousand men, women, and children filtered into an obscure structure resembling something out of Hollywood’s science fiction pictures of the day. The Aerodome – “fire-proof canvas suspended from aluminum ribs” – housed General Motors’ plea for the public to become more interested in the wonders of science and was the main attraction in GM’s “Parade of Progress” – a traveling exhibition of innovation and invention. The audience found their seats as Leo Schreiner, general manager of the local GM plant, took center stage to address the damp crowd: “Here in the Trenton area, American industry makes everything from steel to pottery, steam turbines to light bulbs, overalls to oyster crackers.” General Motors was proud to be included in the mix, but Schreiner proclaimed “America is only beginning to tap the limitless resources that are waiting to be put to use by mankind.” The mid-20th century saw not only GM but countless other institutions and industries expanding their reach into small towns and big cities, from chemical processes to concrete infrastructure. This was the same march of progress that propelled 15th and 16th century colonists to the New World and ignited 19th-century frontier exploration. “It is this progress that is the theme of the Parade of Progress.”[1]

Though GM advertisements promised the “Parade of Progress” was “not an Automobile show” with “nothing to buy,” the event’s exhibits differed. As historian Nathaniel Robert Walker argues, “the core message of General Motors’ urban design exhibits was clear: if any community hoped to enter the imminent future of scientific progress and economic prosperity, it would have to be drastically transformed to embrace high-speed motoring.”[2] This message resonated throughout cities across the country which were struggling with flailing industries and declining tax-bases. Businessmen and elected officials matched their visionary ideas with the technical know-how of engineers and planners to produce vast systems of highways which would release collective progress from the mangy grip of urban blight. The City of Trenton did not want to fall behind.

This march of progress meant the sacrifice of many public and personal goods. To make way for the highways, homes were demolished, businesses shuttered, and parks razed. Here in Trenton, one of the oldest state capitals in the country, the fate of its second largest and most beautiful park was debated vigorously while the East-West Highway loomed in the distance. At the heart of this public debate – which ranged from the 1940s to the 1960s – was a group of small businessmen from nearby South Broad Street, along with concerned citizens writing in to the local Trenton Evening Times and attending public hearings. These citizens foregrounded the preservation of Stacy Park in a discussion which had initially ignored it; the aptly titled South Broad Street Merchants Association, while not for the destruction of the park, protested the portion on the highway that came after Stacy Park and which would run through their district. This section of the road – known as the Assunpink Way, named for the creek whose route it would follow – was meant to connect the East-West Highway along the Delaware River with the Trenton Freeway in the city, an effort to relieve traffic congestion at one of Trenton’s busiest intersections and allow free-flowing traffic to move in and out of the city with ease.

Over the years, as more and more park-land was ceded to the highway, the Merchants effectively resisted the construction of Assunpink Way. However, they were not against the highway on its own, just this particular section; still further, they only quarreled with the type of construction. (The Merchants argued against an elevated roadway, which, they argued, would negatively affect their businesses; a surface-level and depressed roadway would be fine.) The East-West Highway – also known as John Fitch Way – was recognized, even by the Merchants, as a necessary project to cement a prosperous future for Trenton. Most citizens wanted the highway, too, with 69 percent approving of the East-West Highway (and specifically the Assunpink Way) in a 1948 poll.[3] Despite their admiration for the park, Trentonians knew the highway must be built. When the highway debate was eventually absorbed into the behemoth urban renewal program at the close of the 1950s, stronger business interests organized around redeveloping their own commercial district; the Assunpink Way was scraped with these plans, and the highway redirected away from the business district to further cover Stacy Park, much to the dismay of everyone involved.

Herein lies the core difference between Trenton and other American cities. Whereas cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Baltimore had organized resistance, Trenton had no significant civic participation with regard to its precious park. Certainly, civil rights groups such as the NAACP came to the aid of those whose homes stood just beyond Stacy Park. Even a recreationally-oriented local civic group made little effort to defend the park. Aside from some stray individuals, business and commercial interests commanded the public forum on the highway. This paper seeks insights into this question, but one thing is certain: business interests in Trenton overtook an unorganized faction of park supporters in the civic process, allowing them to steer the public discussion and, eventually, the highway itself. Business interests in Trenton steadily took advantage of a lack of organization amongst park supporters to steer the public discussion and, eventually, the highway itself.

This paper will engage social, cultural, and environmental histories. Eric Avila’s The Folklore of the Freeway challenges the “bourgeois counterparts to the inner-city uprising” against highway construction, focusing on racial and class differences to demonstrate the “skewed geographies of power.”[4] This paper will show how a higher-class neighborhood can display a lack of organization, precluding any possible protests from marginalized communities. Alison Isenberg has contributed immensely to the understanding of the commercial packaging of cities with Downtown America; this paper will further add to this understanding, employing similar methods to non-commercial space.[5] With Environmental Activism and the Urban Crisis, Robert Gioielli writes of an organized and unified resistance to the highway in Baltimore, and how those activists utilized an environmental framework in their work. This paper will demonstrate a story of disunity and disorganization in the grassroots struggle against the highway in Trenton, and while some harbored an environmental view towards the park, others saw pure economics.[6]

This paper will be divided into two sections. The first will focus on the initial organized effort put forth by the South Broad Street Merchants against a planned road through their district. They were able to stave off the highway while employing a commercial argument, but those who supported the local park did so for environmental and economic concerns. They did not organize and failed in their cause; they are the other focus in this first section. This first section sets the stage for the second section – the commercialization of the highway debate by larger and larger business interest bent on redeveloping the downtown area. The highway planning was absorbed into the urban renewal program of the late 1950s and allowed for Route 29 to ultimately cut through the entirety of Stacy Park.

Snow fell softly on South Broad Street when clerks and customers burst from the storefronts and onto the pavement. “A disastrous all-night fire” began to ravage the small businesses of Trenton’s main commercial district at the closing hour on February 10, 1948. The alarm box across the street was pulled and firefighters got to work. Though they employed “every device known to scientific fire fighting,” the excessive blaze sent them “knee deep” in the nearby Assunpink Creek for more water. The fire burned into the morning when it eventually died out, but the smell of the burnt dresses and linoleum acted as an aromatic display of the vulnerabilities of the area following “the worst fire ever to strike the downtown business district.” For after the embers cooled and the ashes settled, the State of New Jersey would seek to brush away the ruins to make way for progress.[7]

This fire inadvertently set into motion a long-paused discussion about the highway in Trenton. There existed a need for an east-west thoroughfare to ease traffic congestion in the western portion of the city (particularly at the intersection of Calhoun and West State Streets), and then another roadway to connect that highway with the future Trenton Freeway across the city. The South Broad Street businesses above the Assunpink Creek had represented a roadblock for state and city governments in constructing an Assunpink Way along the bed of the creek to link the two highways. The Trenton Evening Times expressed a renewed eagerness for the project just one week following the tragic fire, stating “this is an opportune time for initial action toward improvement” and “establishment of an east and west-bound thoroughfare.”[8] But the road would have to cut through a beloved park on its way to the business district while imposing on the homes of higher-class residents. While disorganized park supporters who invoked environmental and economic concerns failed to fight the highway, the merchants of South Broad Street organized around business interests and were able to stymy the planning process and hold off construction of the Assunpink Way. This set the stage for larger commercial interests to take control of the civic process down the line.

The business owners quickly formed the South Broad Street Merchants Association in protest of the proposed Assunpink Way. At their first meeting in early March, they argued the road would reduce the area to “a second rate shopping district.”[9] The City Commission held a hearing to allow State Highway Commissioner Spencer Miller Jr. to explain the project, proclaiming the road “will meet with the approval of the residents of Trenton.” Albert B. Kahn, a lawyer representing the Merchants, rebutted that claim and made the case that the potential loss in ratables (tax revenue) would increase taxes for everyone else: “You can see that this is a problem of grave concern to the whole city and not just to the South Broad Street merchants,” Kahn complained.[10] The conflation of business interests with the interests of the general public was a chief tactic utilized by boosters in the 20th century, but some Trentonians rejected this approach now. The Times again editorialized that “selfish business interests blocked this project” once before, and they “must not permit a recurrence of this great mistake.”[11]

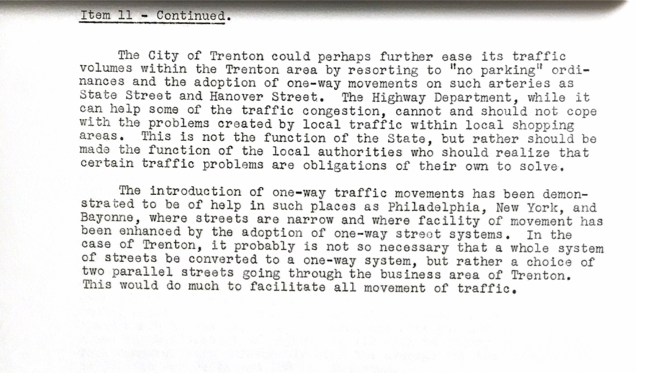

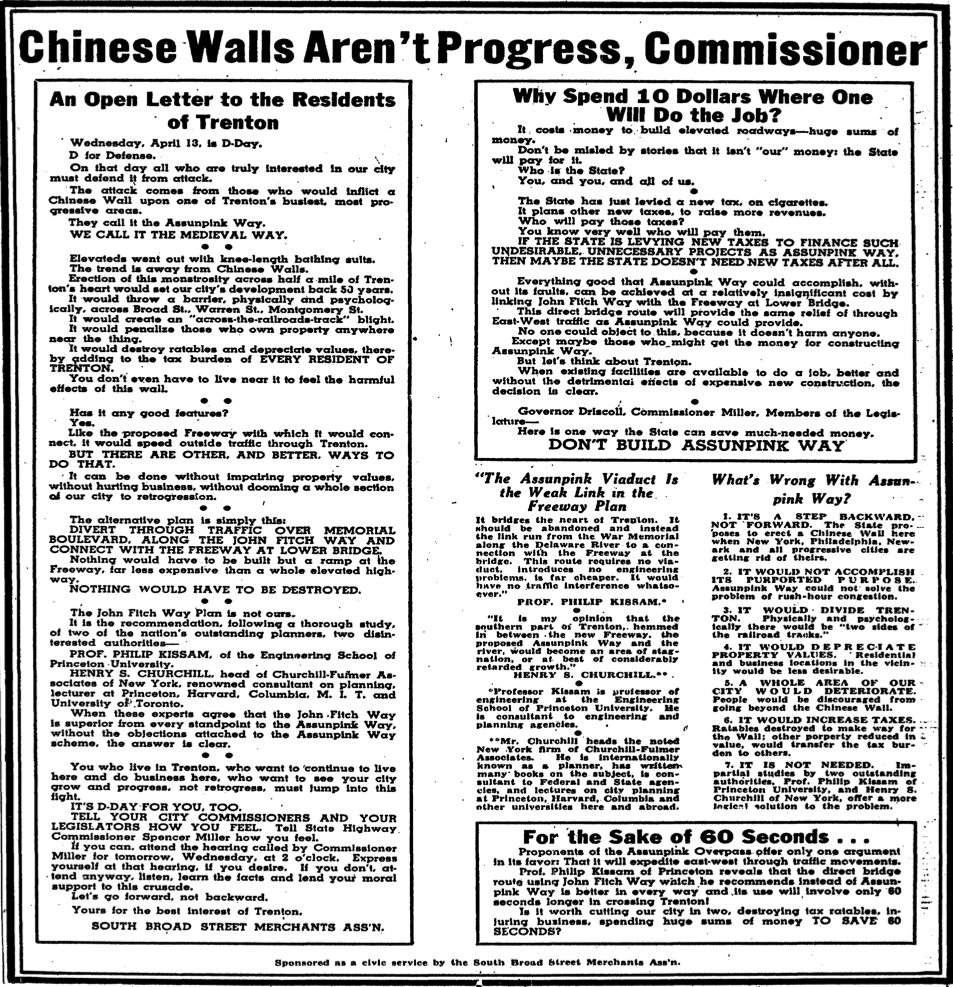

The public feud intensified when some of the businessmen obtained permits to rebuild their stores right before a scheduled public hearing at the end of March. In an act of appeasement, the SHD agreed to delay the hearing if the merchants withheld any new construction. In the meantime, the Merchants did what many resourceful organizations did in the country when the highway threatened their community: they hired outside engineers to study the plans independently. They expressed dismay at the plans, and the Merchants advertised these findings in the Times on the day of the public hearing. The advertisement was an open letter to the residents of Trenton, claiming they were being attacked by “those who would inflict a Chinese Wall upon one of Trenton’s busiest, most progressive areas.” It continued with the Merchants’ financial perspective that the elevated highway – “a barrier, physically and psychologically” – would “destroy ratables and depreciate values” and increase taxes for everyone in the city. “You who live in Trenton,” the Merchants’ implored, “who want to continue to live here and do business here, who want to see your city grow and progress, not retrogress, must jump into this fight.”[12] William Kravitz, president of the Merchants, testified at the public hearing with much the same sentiment: “The Assunpink idea has been exposed as an unjustifiable expenditure of public funds” that would “depreciate a whole neighborhood and ruin one of Trenton’s principal business areas.”[13]

It is important to note that the Merchants did not oppose the highway in its entirety; hardly anyone did. They only objected to the road’s imposition on the business district. More specifically, they opposed an elevated highway; a surface-level or depressed road would suffice, but they did provide an alternative as suggested by their outside advisors. In the same open letter lambasting the Assunpink Way, the Merchants proposed what they deemed a more efficient and cheaper plan. “Everything good that Assunpink Way could accomplish, without its faults, can be achieved at a relatively insignificant cost by linking John Fitch Way [the East-West Highway] with the Freeway at Lower Bridge.”[14] The Merchants argued that this plan would not cause any deterioration or decline in property values, while achieving the same goal of relieving congestion for east-west traffic. However, this plan would have the highway run directly through the largest portion of the city’s second largest and most cherished piece of undeveloped land: Stacy Park.

In just over two months, the Merchants successfully halted – at least for a while – the plans for an Assunpink Way. Mayor Donal Connolly, being sufficiently pressured by the businessmen of his city, called for a new study of the controversial road.[15] In the meantime, the conversation turned to the rest of the East-West Highway – a project that would be completed in several phases. Debate continued uninterrupted as the city rushed to complete its highway system in time for the new US Steel plant’s opening across the river in Morrisville, Pennsylvania; as the Times pointed out, “the plant, with its 5,000 new employees and its truck transportation, will intensify Trenton’s traffic congestion in the areas around the lower and the upper Delaware River bridges.”[16] At this stage, the road would follow the bed of the Sanhican Creek, which flowed through the length of Stacy Park, from Lafayette Boulevard to Parkside Avenue.

Stacy Park had yet to be a factor in the highway discussion. As one concerned citizen noted in a letter to the Times, “there is apparently no concern whatever over the suggested abolition of one of the all too few parks in our city.” The author of this letter felt disregarded by those in power who failed to appreciate the “overhanging trees and picturesque bridges which distinguish Trenton,” not to mention that the park is “enjoyed the year round by residents from every section of the city” who would suddenly have one less natural space in a city already lacking such land. “On Summer evenings and week-ends,” the author continued, “when the plutocrats of our city are at the shore, those less fortunate find rest and peace and relaxation under the trees along the river and creek banks.”[17] If “those less fortunate” were to lose the environmental sanctity of their park, the upper-classes of the area protested for economic reasons: “Let’s not destroy the beauty of the Water Power [Sanhican Creek] and the properties of those in the city who are paying the highest taxes,” wrote “Beauty Lover” to the Times.[18] Though these two demographics shared a stance on saving the park, albeit for different purposes, there was no unified resistance towards the highway from park supporters. Individuals attended meetings or wrote their opinions to the Times, but no organized body stood in the way of the highway. In 1953, the Atterbury-Cadwaladar Civic Association (ACCA) – comprised of residents from Trenton’s West End – polled its members on their thoughts about the highway; 50.5% voted in favor, while 49% “vigorously opposed” the plan. In a letter to the Mayor and City Commissioners, Gordon Philips, president of the ACCA, issued a word of caution following the vote. “[T]he roadway should be in keeping with the beauty of the area,” including “rustic lighting, trees, grass, and other important matters which would assist in attempting to prevent a large decrease in property values.” He continued on this theme, stating that the road “might take away one of the last remaining high taxed residential areas within the city limits, and your planning should have this in mind at all times.” Furthermore, the ACCA laid bare its acquiescence in broader terms of sacrifice in the face of progress: “All of use in Trenton would hate to see the end of Stacy Park, but the majority…indicates progress must go on even at the cost of losing this beauty spot.”[19] The upper-classes of Trenton bowed to the highway, unable or unwilling to organize with other factions to stop the destruction of Stacy Park.

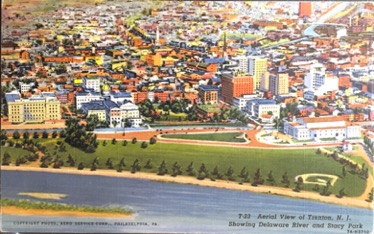

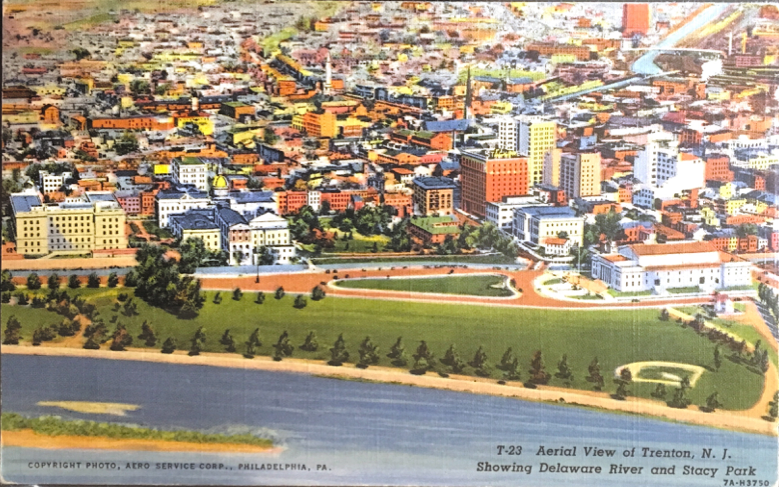

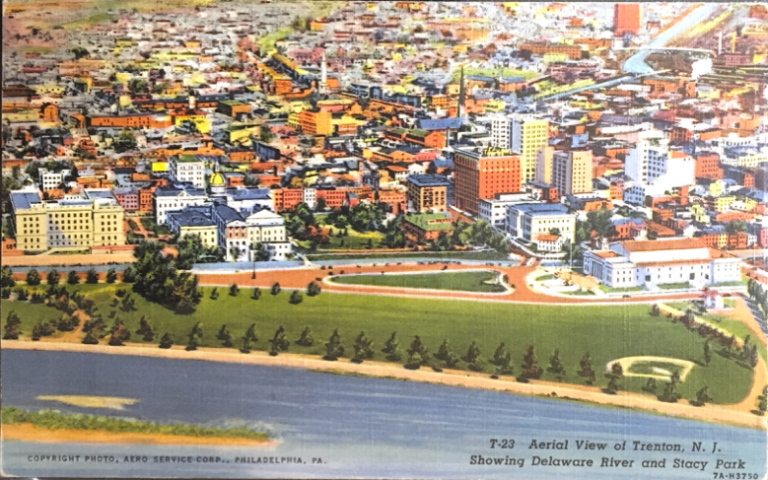

Postcard depicting Aerial View of Trenton, N. J., Showing Delaware River and Stacy Park.

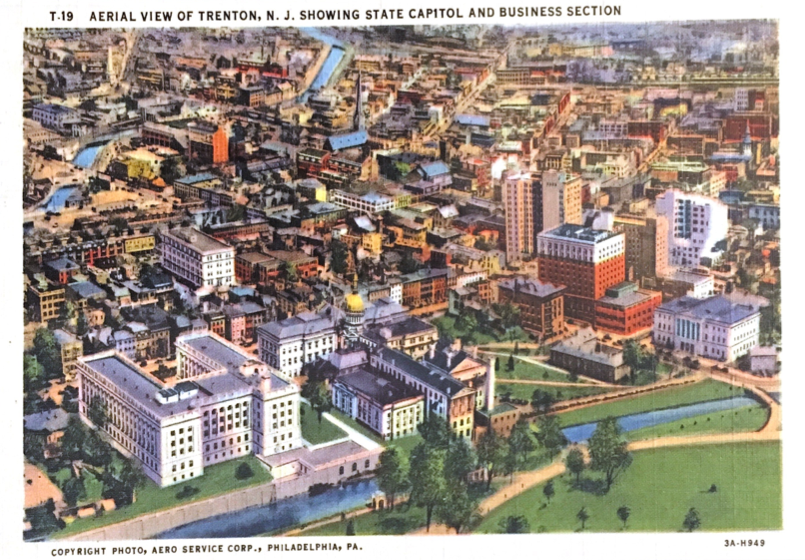

More interesting, however, was the importance placed upon the park by business and public leaders. Stacy Park was seen as an attraction – a destination, even, to visitors and residents. This is evident based on a postcard created in the previous decade, which displays Stacy Park as a pristine, lush, and open space. The Aero Service Corporation of Philadelphia – which provided business and government with aerial photographs for various purposes such as planning – photographed this area of South Trenton, New Jersey, sometime after 1932. The image features the Delaware River, Stacy Park, the State Capitol, War Memorial Theatre, and the main business district. Around 1937, Lynn H. Boyer published a colorized version of the image as a postcard for Chicago-based German postcard giant Curt Teich (famous for their “Greetings from…” series).

Postcards like this exist for many places around the country. The artists at Curt Teich had the express purpose of colorizing whatever photograph was placed on their desk in an effort to beautify its subject. As Isenberg notes in Downtown America, the postcards “reflected the commitment of business groups, city leaders, and design professionals to remake and promote downtown as an ordered, regulated, dignified civic destination.”[20] Such postcards typically idealize the Main Street of the city’s downtown area, with removed blemishes like pedestrians, wires, and poles. What is left is “an image of a clear commercial vista,” Isenberg explains, “in which the eye could travel like a consumer, uninterrupted by the bodies of other shoppers.”[21] This postcard of Stacy Park is a product of similar tactics. When initially viewing this postcard, one might be struck by the lack of people enjoying themselves in the park. However, within this image, opportunity awaits. The many trails, baseball field, and access to the river, present the many possibilities of leisurely activity. One might find while strolling the clean walkways a peaceful family fishing at one end of the park, and a little league championship game at the other. Despite the emptiness in this picture, the park was constantly occupied and offered recreational space for countless citizens whether it be for leisure or civic events (Boy Scout activities, veteran memorials, traveling exhibitions, and sanctuary for homeless people in need of rest).

Natural space is vitally important to a just society. The people of Trenton relied upon Stacy Park not just for recreational use but for civic and social purposes; it was the heart of the community and presented equitable access to not just open air and land but to the lively waters of the Delaware River for those still residing in the city proper. Furthermore, the park occupies prime space at the seat of state government. Stacy Park acts as a hub for Trenton, where the city’s daily operations revolve around. It is a meeting ground for residents, shop-owners, state workers, guests at the Stacy Trent Hotel, and maybe a crowd filtering out of a show in the War Memorial (completed in 1932 as tribute to the veterans of World War I). As the rest of the city fades away into the background, the park remains in the foreground – the heart of the city.

The citizens of Trenton pleaded for the preservation of this park, but would in the end apprehensively approve of sacrificing the land if it solved the city’s traffic problems. After the construction of Route 29 through the park, a sliver of land remained along the river, allowing enjoyment for whomever risked crossing the busy road. When one of the phases of construction was finished about a mile north of this particular location, 3-year-old Christopher Thompson attempted to cross the highway in order to reach the park but was struck dead by a car on the fresh asphalt of John Fitch Way.[22]

In 1956, the Assunpink Way debate was renewed, and the Merchants had a new president, C. E. Benjamin. The talking points echoed from the past: an elevated road would kill all business south of it. Under threat of demolition, Benjamin said, South Broad Street stores were going out of business. The new president even wrote a letter to the Times further stating their case. An overpass would discourage modernization and put “a damper on all new investment plans,” he wrote. The Merchants now proposed an underpass which would increase “future tax revenues by preserving the business value of the area.” To be clear, they were on the side of progress – not standing in its way.[23] The downtown beautification pioneered by businesses in the past, however, was now transforming in the era of urban renewal.

New commercial interests formed around the guiding principle of redevelopment. As the Assunpink Way was debated in the Chamber of Commerce – whose possible rejection “would kill the link plan” – the Greater Trenton Council was created in May 1957. Organized at the behest of Mayor Connolly, the GTC focused on “the development of greater economic opportunity, cultural advancement and recreational facilities of Greater Trenton;” in short, the Times wrote in a promotional front-page story, “it would make Trenton a better place to live and do business in.”[24] A year later, the GTC was meeting with the SHD and the Legislative Building Committee to discuss traffic solutions for the city, and possibly scraping the Assunpink Way altogether. The plans, however, would feed into “the shape and character of the John Fitch Way” urban renewal project.

Throughout 1958, business interests in Trenton raced to develop their own plans for the city’s highways. However, these plans went much further than solving traffic congestion. The Merchants’ plan “suggests the creation of a ‘shopping center’ arrangement at the core of the downtown district,” while the late revealed GTC plan would “not only solve the chronic mid-city traffic headache but permit a vast expansion of the business district within the encompassing highway network.”[25] The back and forth of commercial and highway planning, however, came back to the Assunpink Way again. The city would adopt one of the proposals into its urban renewal program, but there was one catch. The program had to match the city’s master plan, which featured the Assunpink Way; neither of the business proposals included that road.

The Trenton Planning Board for the first time rigorously debated the Assunpink Way. The Board Chairman, S. Carl Mark, who initially had backed the road, had “a change in thinking” after hearing about the GTC plan. He called for yet another public hearing, which irked another board member who exclaimed, the GTC plan “has never been approved by anyone,” and that “nobody has ever checked to see whether it would work.” A public hearing would be for the benefit of Mark and the South Broad Street merchants, “not the city’s.”[26]

At this point, the Merchants were being overrun by the GTC, whose plans were bigger and more expensive. At the next public hearing, city traffic engineers complained of the further delays of the Assunpink Way. One of them stated, “I have it from a State Highway Department source that had the Greater Trenton Council not opposed this improvement, the Assunpink Way would have been on this year’s construction program.” The designers of the GTC plan argued that the “Assunpink Way would defeat the purpose of the entire downtown plan, including the loop concept and the clustering of various land uses.”[27] The Planning Board eventually called for a new traffic study, holding off a decision regarding the road despite Chairman Mark’s attempts to scrap it.

By June 1959, the GTC finally unveiled its full master plan. It was a complete urban renewal package for the central business district. Presented to a group of over 300 officials and community leaders, the GTC promised “new downtown shopping attractions will thrive among the best of existing stores, all of them near modern parking facilities,” while “new street patterns will assure the convenient flow of vehicles and pedestrians among all the specified new land uses.” All this would amount to “an attractive urban center with which Trenton can grow and serve its suburban hinterland.” Without these drastic measures of redevelopment, the GTC warned the city would incur a net loss in retail business of $250,000,000 by 1975. The Times hailed the plan as “bold” and “ambitious,” as the public officials applauded their gumption.[28]

Just six months later, another, bigger commercial plan was announced. Lit Brothers department store unveiled its “Capitol Center” plan – a massive complex featuring the largest department store in the state outside of Newark and creating new spaces for other businesses and commercial interests. Lits’ president – S. Carl Mark – proclaimed that “the one most critical factor” in the plan is the abandonment of the Assunpink Way. Such a road would interfere with their benevolent redevelopment plans for the central business district. In fact, the Assunpink Creek was seen as a natural asset by Lits, which “could become an attractive center strip of a landscaped mall, bordered by promenades behind which would rise shops and two-story professional buildings.” Trenton needed this kind of bold and imaginative planning to keep up with other, more progressive cities, Mark said. Not to mention, Lits “does not enjoy contemplating relocating our store on the perimeter of Trenton.” The day after this announcement, Mark resigned as chairman of the Planning Board.[29]

Despite this obvious conflict of interest for Mark, the community leaders wholeheartedly endorsed the plan. The Times hailed it as “the most important commercial redevelopment in Trenton’s history and as a vital contribution to the transformation of Trenton, now in its first stages of its efforts to emerge from the civic deterioration of earlier years.”[30] New Mayor Arthur Holland was “elated at the entrance upon the Trenton scene for the first time of large scale local private enterprise purchasing interest.”[31] The Merchants, however, felt slightly different. Regarding the clause in the Capitol Center plans that they would become renters under Lits, they were “strongly opposed to being forced into the position of tenants.” They continued: “First concern should be accorded to the uprooted businesses, not to outside private interests which are not even located in the redevelopment area.” They proposed their own cooperative, but it never came to fruition.[32]

The other residents in the redevelopment area who were displaced from their homes (officially deemed “slums”), were not welcomed as such by Lits. As Mark said at the unveiling ceremony in 1959, “we don’t propose to erect a commercial center which backs into a slum area.”[33] The new residential sites planned by Lits “would accommodate middle and upper-middle income families and would have rentals of $110 to $150;” in addition to these apartments, they would erect “town houses of two to four units. A two-unit house would be designed to sell for about $18,000.” These homes were considerably more expensive than what they replaced, but they were supposed to be. They were designed to attract a larger tax base to increase city revenue, for “the success of the John Fitch Way is important to the continued success of Lit Brothers and the success of Lit Brothers is important in maintaining the central core of Trenton.”[34]

The planning process was relatively quiet throughout 1960. However, in December of that year the SHD released their final plans for the city’s vast highway system. Conspicuously absent was the infamous Assunpink Way. In its place was “an elaborate weave of multi-lane roadways to serve the new State office buildings in the John Fitch Redevelopment.” In August, the City Commission voted in favor of the plans as they “faced the unpleasant prospect…that much of Stacy Park back of the State House will have to be sacrificed to highway improvements.”[35] At the final public hearing in September 1961, Edward Meara III, executive secretary and director of the GTC, exclaimed that “we think it is somewhat paradoxical for the state on the one hand to ask the voters to support a $60 million bond issue referendum for the purchase of green acres for parks, and at the same time take existing park land for this new highway right of way when there is an alternative route available.”[36] To add insult to injury, city traffic engineer Otto Ortlieb solemnly stated at a planning board meeting three weeks later that “he saw nothing in the plans for the expressway which is going to aid the flow of east-west traffic in the city.”[37]

The evolution of commercial redevelopment plans did not stop with the Lits Brothers’ Capital Center. Soon after, the idea of the “Trenton Mall” was introduced and debated, and eventually shot down. No significant commercial redevelopment scheme was acted upon, yet the highway continued on past the park and through another lower-class community in the 1990s. The business interests of the postwar-era sought to develop their city in their idealized image; Trenton was no different in this regard. In other cities, however, anti-highway protestors were able to organize to put up a fight; in Trenton, there existed no such fight. The civic void was filled with commercialization and urban renewal, none of which succeeded in renovating the city out of despair. Trenton is still attempting rejuvenation through commercial enterprises, ignorant of the history of highway planning and urban renewal or just plain stubborn.

[1] “GM’s Parade of Progress Opens 5-Day Visit Here,” Trenton Evening Times (Trenton, NJ), May 7, 1954.

[2] Nathaniel Robert Walker, “American Crossroads: General Motors’ Midcentury Campaign to Promote Modernist Urban Design in Hometown U.S.A.,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 23, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 91.

[3] “Times Poll Reveals Majority of Trenton Residents Remain in Favor of Assunpink Way,” TET, March 15, 1948.

[4] Eric Avila, The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 2.

[5] Alison Isenberg, Downtown America: A History of the Place and the People Who Made It, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

[6] Robert Gioielli, “‘We Must Destroy You to Save You:’ Baltimore’s Freeway Revolt,” in Environmental Activism and the Urban Crisis. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014): 73-103.

[7] “General Alarm Fire Sweeps Through Stores Here,” TET, February 11, 1948.

[8] “Fires and Trenton’s Future,” TET, February 19, 1948.

[9] “Elevated Road at Fire Scene Stirs Protest,” TET, March 10, 1948.

[10] “Miller Gives Assurance Assunpink Way Will Meet With Residents’ Approval,” TET, March 12, 1948.

[11] “Obstructionists at Work,” TET, March 15, 1948.

[12] “Chinese Walls Aren’t Progress, Commissioner,” TET, April 13, 1948.

[13] “Assunpink Way Hearing Starts as Miller Pledges Full Study of All Factors,” TET, April 14, 1948.

[14] “Chinese Walls,” TET.

[15] “New Road Proposal is Studied,” TET, April 22, 1948.

[16] “East-West Highway?” TET, March 20, 1951.

[17] G. S., “Would Save Park,” TET, April 8, 1951.

[18] Beauty Lover, “Cites Park Value,” TET, April 27, 1951.

[19] Letter from Gordon A. Philips to The Honorable Mayor and Commissioners, February 4, 1953.

[20] Isenberg, Downtown America, 44.

[21] Ibid., 69-70.

[22] “Automobile Kills Thompson Boy, 3,” TET, July 21, 1957.

[23] C. E. Benjamin, “Assunpink Way,” TET, May 3, 1956.

[24] “Today’s Task: Tomorrow’s Trenton,” TET, May 12, 1957.

[25] “S. Broad Merchants Back Midcity Perimeter Highway,” TET, August 20, 1958; “Planners Call For Loop Highway Around Trenton’s Business District,” TET, October 28, 1958.

[26] “Vote To Air All Mid-City Road Plans,” TET, January 13, 1959.

[27] “Assunpink Way Backed, Opposed,” TET, January 27, 1959.

[28] “Sweeping Redevelopment Plan is Hailed As Trenton’s Hope,” TET, June 12, 1959.

[29] “Lits Proposes $4,000,000 Fitch Area ‘Capitol Center,’” TET, December 14, 1959.

[30] “Capitol Center,” TET, December 15, 1959.

[31] “Hits Mark on Lits Plan,” TET, December 18, 1959.

[32] “Merchants Draft Own Redevelopment Plan,” TET, December 29, 1959.

[33] “Sweeping Redevelopment…” TET.

[34] “Capital Center’s Fitch Plan Includes Apartment Units,” TET, February 10, 1961.

[35] “Fitch Tract Roads OKd, Cut Stacy Park,” TET, August 10, 1961.

[36] “Air Fitch Parkway Tie to Burlington,” TET, September 1, 1961.

[37] “May Give Up 22 Acres to Expressway,” TET, September 20, 1961.

Primary Sources:

Primary Source Report

Aero Service Corporation. Aerial View of Trenton, N. J. Showing Delaware River and Stacy Park. Postcard stamped July 23, 1956.

–. Aerial View of Trenton, N. J. Showing State Capitol and Business Section. Postcard stamped October 13, 1954.

- Location: My own collection.

- Description: Postcards showing from two angles a portion of my research site – South Trenton business district and Stacy Park along the Delaware River. Though the cards are stamped in 1954 and 1956 – during construction of the Assunpink Way – the view is without the new road; an exact date of the postcards production is not available. These images – artists’ depictions – display the beauty and charm of the area, lending visual aid to the highway opponents’ pleas to save their cherished park. The postcards also demonstrate that this particular area was proudly shown by locals and visitors to people across the country. I plan to use these postcards to not only help show the specific environment in which my historical actors played, but how these historical actors saw it themselves.

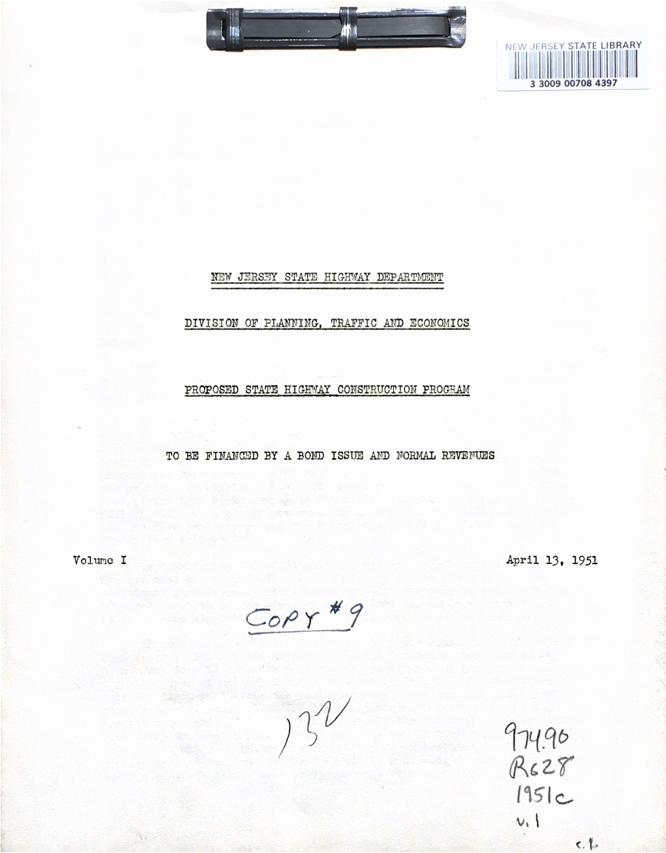

New Jersey State Highway Department: Division of Planning, Traffic and Economics. “Proposed State Highway Construction Program.” Government Report, Trenton, NJ, 1951.

- Location: New Jersey State Library (scanned from the original).

- Description: A typed collection of items detailing the next five years of proposed highway projects by the State Highway Department. Item 11 is the Route 29 extension (Assunpink Way, Lafayette Boulevard extension, John Fitch Way) which is the focus of this research project. The document – which is just shy of 1 ½ pages – describes the drastic need for a relief route for east-west traffic, which at the time clogged the intersection of State and Calhoun Streets daily. The plan proposes to overpass Calhoun Street entirely with an extension of Route 29 from Stockton Street (in the heart of the city) to Parkside Avenue (a suburb of Trenton a mile and a half up the Delaware River) to help relieve State Street. The Highway Department claims that with this plan, vehicles could reach the suburbs more easily by avoiding the “central business area of Trenton.” I plan to use this document to help demonstrate the aims and motives of the State Highway Department in the construction of this road. At the same time, this document has interesting insights into how the Department viewed the seemingly arbitrary limitations of their power in terms of traffic control jurisdiction. The Department here notes that, despite their willingness to move traffic away from the business district of Trenton, it “cannot and should not cope with the problems created by local traffic within” those same areas.

Shuman, Eleanore Nolan. The Trenton Story. Trenton: MacCrellish & Quigley Company, 1958.

- Location: Lawrence Public Library.

- Description: While this book was published one year after the completion of the Assunpink Way, its contents are very much pertinent to the contemporary social, cultural, and political apparatus of the capital city. The book is not an official government document, but, as Trenton Mayor Donal Connolly wrote in a letter placed before the author’s preface: “The Mayor’s Citizens Committee and the businesses and industries of this community have made a significant contribution to the people of Trenton in sponsoring and financing this publication.” It is a document conjured by the city’s own elite to showcase its history and plans for the future in order to demonstrate how Trenton, as Mayor Connolly wrote, “richly deserves her high rank among the four leading historic American cities.” I plan to utilize this book to incorporate what could be described as the collective testament of the City of Trenton. In addition to this grand purpose, The Trenton Story also provides histories of various notable organizations, institutions, people, and places, such as John Fitch (of John Fitch Way), the city’s highways, and Stacy Park. This, too, can prove useful in contextual analysis and description of my site and historical actors.

South Broad Street Merchants Association. “Chinese Walls Aren’t Progress, Commissioners.” The Trenton Evening Times. (Trenton, NJ), April 13, 1948.

- Location: In The Trenton Evening Times, found in the New Jersey State Library. Accessed and downloaded page digitally.

- Description: A nearly half-page advertisement taken out by the South Broad Street Merchants Association in the Trenton Evening Times. Along with several quotes throughout news articles in the Times, this advertisement is the most significant source I have from the Merchants themselves. In big, block lettering, the advertisement shouts at State Highway Commissioner Spencer Miller that “Chinese Walls Aren’t Progress;” in actuality, it is an open letter not only to the State but an appeal to residents of Trenton. The merchants here are making their case to the public against the Assunpink Way (which they deem the “MEDIEVAL WAY”) by using dramatic language along with sober, matter-of-fact opinions of independent engineers they hired to analyze the highway plans. This advertisement will be instrumental in examining the views and approach of this anti-highway group, showing how they interacted with their community and their government in the same space. Until I discover more documents from the South Broad Street Merchants, this will act as their treatise on the Assunpink Way.

The Trenton Evening Times. (Trenton, NJ), 1947-1957.

- Location: New Jersey State Library. Accessed and downloaded digitally; available remotely.

- Description: The Trenton Evening Times is the definitive primary source on the overall story and timeline of the development of Assunpink Way. There are over 100 articles detailing different aspects of the project, covering public hearings, board meetings, and official announcements. The newspaper also features a couple dozen letters to the editor from city residents pertaining to the highway’s construction, providing a valuable insight into how more locals viewed the situation. An important disclaimer, however, is warranted: the Times was adamantly pro-highway, as is evident throughout their editorials. Some stories from the perspective of the Merchants, for instance, could be found buried 15 pages into the paper while stories featuring the advancement of the project in the bureaucracy were almost always on the front page, above the fold. (The Trenton Evening Times was also a sponsor of another of my primary sources – The Trenton Story.) However, the Times is a reliable source in outlining the narrative of the highway’s development – from inception to completion.

Secondary Sources:

GIOIELLI, Robert R. “‘We Must Destroy You to Save You:’ Baltimore’s Freeway Revolt.” In Environmental Activism and the Urban Crisis. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014.

Not only does Gioielli neatly couch the story of Baltimorians’ fight against the city’s highway system in an environmental framework, but he also displays clearly the grassroots experience working with outside parties in the democratic process. The Baltimore story is also one of coalition-building amongst city people of color and suburban whites; as far as I can tell, there was no formal coalition of disparate groups formed in the fight against Trenton’s urban highway system. This is one interesting distinction of the Trenton example; another is the (up to this point) lack of evidence pointing to a race as a concern amongst local citizens.

AVILA, Eric. The Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Avila’s book features stories of freeway revolts around the country and over time, focusing on communities of color. He contends that “if we limit our reading of the folklore of the freeway to the language of class and class struggle,” the role of race becomes obscure in the history of postwar urban highway construction. This is certainly true, but in my own research of the Assunpink Way and Trenton Freeway the publicized opposition to the projects are not so much racial – or any social marker, for that matter. They are small business owners hoping to retain their local community of shoppers. In addition to this scholarly contrast, I find much in Avila’s discussion of the modernist city – an idea very much on the minds of proponents of Trenton’s postwar highway system. He details the intellectual history of city planning as it pertains to traffic control, but also the bureaucratic process and intricate web of planners and engineers in postwar America; I hope to utilize this as a contextual backdrop for the Trenton story.

MOHL, Raymond A. “Stop the Road: Freeway Revolts in American Cities.” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 5 (July 2004): 674-706.

Mohl develops a set of “ingredients” that make up successful highway opposition in the postwar era – persistent activism and coalition-building; local official support; strong and historic planning traditions; legal action; and subsequent top-down support. Did opponents of the Trenton highway projects conform with this list? If so, how much? How did these actions and particulars help or hurt their fight? It would be interesting to test Trenton’s historical experience against this metric.

SHELTON, Kyle. “Building a Better Houston: Highways, Neighborhoods, and Infrastructural Citizenship in the 1970s.”Journal of Urban History 43, no. 3 (2017): 421-444.

Shelton’s notion of “infrastructural citizenship” is very intriguing. I wish to utilize this approach to examine how Trentonians used infrastructure in a civic manner. Small business owners delved into the tax system to display how the highway would bear down upon the community. Other locals vied for the historic preservation of Assunpink Creek – a notable site during the Revolutionary War in the Battle of Trenton. Shelton writes that “residents used infrastructural debates to assert their rights as citizens;” in postwar Trenton, it was not just residents protesting but community pillars like the South Broad Street Merchants Association. However, this is not to say that a majority of citizens opposed the highway plans. Other residents participated in new, revolutionary civic polling to display their support.

FISHER, Colin. Urban Green: Nature, Recreation, and the Working Class in Industrial Chicago. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

While Fisher’s study focuses on the early twentieth century and lacks any sort of urban highway construction, I believe it will help guide my research and analysis of the second part of Trenton’s highway opposition – those who wished to preserve the city’s popular Stacy Park. Fisher’s work examines the relationship working-class communities had with urban nature; were the park-minded opponents of Trenton’s highway working-class? Was it a broad base of class groups? How did different social groups use Stacy Park and how did they defend it? Another point Fisher – and others – makes is the connection locals make between nature and history. Trentonians also felt historically motivated; not just because of Stacy Park, but of nearby Assunpink Creek.

Image Analysis:

The Aero Service Corporation of Philadelphia – which provided business and government with aerial photographs for various purposes such as planning – photographed an area of South Trenton, New Jersey, sometime after 1932. The image features the Delaware River, Mahlon Stacy Park, the State Capitol, War Memorial Theatre, and the main business district. Around 1937, Lynn H. Boyer published a colorized version of the image as a postcard for Chicago-based German postcard giant Curt Teich (famous for their “Greetings from…” series). This visual piece retained its shelf-life until at least the mid-1950s, when one was mailed across the country from Trenton to Independence, Oregon, right in the thick of a highway debate which occupied the capitol city for decades. The construction of what broadly became known as Route 29 occurred in several geographic phases and bore many names: Lafayette Boulevard extension, East-West Freeway, John Fitch Way, Assunpink Way. In the 1950s, the road’s next phase prompted the State Highway Department and the city fathers to determine the fate of one of Trenton’s most prized and cherished possessions – Stacy Park. This postcard showcases that beloved and invaluable attraction for Trenton’s visitors and residents: a natural refuge from the city’s antics where the crowded cluster of buildings gives way to the great wide open, and which would eventually bow to the march of progress with the completion of Route 29.

After finishing the kind note addressed to them, the recipient of this postcard turned it over to find Stacy Park situated between the Delaware River and the busy city of Trenton. The textured linen of the postcard add vibrancy to the various colors of the city: the striking greenery of the park, the blue waters of the Delaware, and the white marble and red bricks of Trenton’s government and businesses. The center of attention – the largest entity in the image – is Stacy Park, with the portrayal of the city and the river emphasizing the importance of this open space. Though the park is surrounded by important buildings and a flowing river, movement within this space is null; it is free of people and vehicles. Despite the emptiness in this picture, the park was constantly occupied and offered recreational space for countless citizens whether it be for leisure or civic events (Boy Scout activities, veteran memorials, traveling exhibitions, and sanctuary for homeless people in need of rest). In fact, the conspicuous absence of activity next to the sprawling cityscape indicates serenity more than unpopularity. This Edenic-space is untouched by humanity; it is perfect. It offers a retreat from the hustle-and-bustle of modern life for the city-dweller.

The park is not, however, devoid of active space. The many trails, baseball field, and riverfront access, present the many possibilities of leisurely activity. One might find while strolling the clean walkways a peaceful family fishing at one of the park, and a little league championship game at the other. Fanning outward from the baseball field is the skyline of Trenton: separate from the park, yet connected by charming pedestrian bridges over the Sanhican Creek (AKA the Water Power) – the future bed of Route 29. Stacy Park acts as a hub for Trenton, where the city’s daily operations revolve around. It is a meeting ground for residents, shop-owners, state workers, guests at the Stacy Trent Hotel, and maybe a crowd filtering out of a show in the War Memorial (completed in 1932 as tribute to the veterans of World War I). As the rest of the city fades away into the background, the park remains in the foreground – the heart of the city.

Natural space is vitally important to a just society. The people of Trenton relied upon Stacy Park not just for recreational use but for civic and social purposes; it was the heart of the community and presented equitable access to not just open air and land but to the lively waters of the Delaware River for those still residing in the city proper. The citizens of Trenton pleaded for the preservation of this park, but would in the end apprehensively approve of sacrificing the land if it solved the city’s traffic problems. State and city planners around the country throughout the postwar era arranged for the desecration of natural spaces such as Stacy Park for various urban renewal projects; and if total destruction did not occur, access to these spaces was severely limited. For instance, after the construction of Route 29 through this park, a sliver of land remained along the river, allowing enjoyment for whomever risked crossing the busy road. When one of the earlier phases of construction was finished about a mile north of this particular location (Stacy Park stretched a few miles along the river), 3-year-old Christopher Thompson attempted to cross the highway in order to reach the park but was struck dead by a car on the fresh asphalt of John Fitch Way.

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews: