The Government or Ronson: Who’s to blame for the poisoning of Ironbound citizens?

by Alexandra Vidal

Site Description:

The modern-day Ronson site consists of 19 family homes that are at continuous risk of vapor intrusion from an industrial chemical Trichloroethylene (TCE). This occurred because these family houses were built on top of the remnants of the chemical waste left behind Ronson inc. This outcome shows the failure of government at the federal and local level. At the federal level, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission did not have the adequate regulations in place to assess the radioactive materials that were left behind Ronson in the site. At the local level, the failure consists of a lack of effort into properly investigating environmental issues on the site when approving the sale of the land to a home developer.

This paper seeks to evaluate the factors that led to the site. The questions being asked are: How did this predicament come to be? In what ways did the bureaucratic nature of the American government contribute to it? How did the bureaucratic inequities of federal and local agencies cause the creation of the site? To what extent can the socio-economic factors of the Ironbound answer this question?

Final Report:

For years Ana Stival and her husband Fabiano DeSilva saved their hard earned money with hopes of one day purchasing a home for their growing family. Then one day, out of the blue, 19 family homes were built in Manufacturer’s Place in the Ironbound of Newark, all within their price range. They bought one of these homes aspiring to achieve upward mobility, aspiring to remove their family from the congested and broken-down apartment building they once resided in. Every morning they woke up, knowing they had attained the American dream of homeownership.

This dream quickly turned into a nightmare when a few years later they got a letter from New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), that informed them their home should have never been built because it resides on top of an environmental waste site left behind Ronson Metals Corporation, a lighter-fluid company. As well as informing them that the air they have been breathing could be causing fetal heart malformations and kidney damage in adults.[1] This did not just happen to Ana and Fabiano. This is the reality of 19 families in Newark who have had to grapple with the question of whether they’ll be abandoning the homes they’ve created, or deal with the potential health risks if they stay.[2]

How did this predicament come to be? In what ways did the bureaucratic nature of the American government contribute to it? How did the bureaucratic inequities of federal and local agencies cause the creation of the site? To what extent can the socio-economic factors of the Ironbound answer this question?

To answer these questions, a variety of source materials have been analyzed. Government documents have proven especially helpful. The primary documents that will be used are the Health Consultation of the site prepared by New Jersey’s Department of Health Environmental and Occupational Health Surveillance Program, as well as a Civil Action Complaint against Ronson initiated by the DEP. These government documents detail the local and state failures, as well as the clean-up process of the site. The literature on the event is minimal and consists primarily of one article from the Star-Ledger and one from NJ.com. These articles will be used to describe the government’s failures, but will be used mainly to detail the point of view of the residents living in those homes. Most of these documents were created after 2012, which is when the DEP discovered that houses had been built on the site.

The paper will examine the site’s history, giving a background on the Ronson factory and the chemicals that were used there that are relevant to the site today. It will then analyze the failures at the federal level on the ways that the hazardous waste of the site was assessed. The paper will then examine the bureaucratic failures of the local Newark government that allowed the houses to be built on top of the site without a proper investigation. After that, the paper will begin to speculate the possible reasons that may have led to the houses being built in the Ironbound. The paper will then conclude by analyzing the socio-economic factors that may have contributed to the creation of the site.

Ronson Factory Background

Newark has always been known as an industrial city, a place defined by manufacturing and the boom of development. The original Ronson factory was a testament to this perspective on Newark, and the homes that would eventually be built on top of that torn-down factory would attempt to refute that. The photograph above was taken in 1945 and it is an image of the Ronson Art Metal Works factory that resided in Aronson Square. The photographer that created the image is not known, but the photo is archived in the Newark Public Library’s online webpage that details Newark’s history. The website details the importance of Louis V. Aronson, the founder of Ronson, as “one of Newark’s greatest industrial leaders and philanthropists”.[3] This photo, in conjunction with the source material the website supports, shows the extent to which Aronson and Ronson became influential identities in Newark. The image served to show to a newer generation, and even the current Newark generation at the time, the sort of power these entities had over the city. It was so influential far as having a factory running in a square named after the founder of said company.

This image displays a busy street in front of the Ronson factory, with cars going in all sorts of directions. Choosing this particular time in the day to take the photo when there are so many cars passing by the factory can be assumed to have been a deliberate choice to affect how the factory is perceived. Having the traffic be at the center of the image makes Aronson Square and the factory itself seem like prominent entities in Newark. It elevates the status of the factory in the city, making it seem like an integral part of it. One potential interpretation is that the photo served to show the Ronson factory as a beacon of industrial prowess in Newark, becoming a representation of the city of Newark as a place of industry, manufacturing, and opportunity.

This theory is emphasized by the appearance of the Ronson factory itself when compared to the other buildings surrounding it. The first photo is black and white, as it was taken in 1945, and the most notable features with a discernible color difference are the banners promoting the factory. Two of them are of a dark color that appears black in the photograph, and the white banner appears behind those two. All three banners were placed there to emphasize Ronson’s presence in the photo and area as a whole. This becomes even more significant when observing how there are no other discernible buildings or landmarks in the photo. By not showing or having any other notable buildings in the photo the presence of Ronson in Newark is highlighted. This is done to place Ronson at the center of Newark and therefore it’s symbolically at the center of industry.

The manufacturing process that created the products that made Ronson an industrial giant would make the factory notorious because of the site’s environmental hazards. According to the Health Consultation report released by the New Jersey Department of Health in 2015, the factory used “a mixture of rare earth elements used to manufacture lighter flints and strikers”.[4] Trichloroethene (TCE) was one of the chemicals used that would later create the environmental hazard inside the homes.[5]The factory was active until 1989 and the company was required by law to fully cleanup the site according to NJDEP’s Environmental Cleanup and Responsibility Act.[6] Although Ronson was supposed to be cleaning the site according to state law, the factory’s use of radioactive materials for the manufacturing of their lighters subjected them to the supervision of the federal government in site cleanup.

Federal Failures

The cleanup of the site was not handled by the DEP, but instead by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), a federal agency. Since Ronson was dealing with radioactive materials the remediation of the site had to be evaluated by the NRC, a federal agency.[7] The NRC’s involvement started in 1999 and it did not have adequate procedural standards which led to the improper cleanup of the site. Although the NRC is supposed to be in charge of decommissioning toxic waste sites that use radioactive elements, such as Ronson’s, and deciding the type of use those sites could have, the agency had a history of improper site cleanup.[8] This appears to have been a well-known issue in this agency as the concerns of inadequate cleanup of sites were raised to the House of Representatives in a study that was published in 1989. This study found instances where the NRC gave multiple environmental hazard sites “unrestricted use where radioactive contamination was higher than its guidelines allowed.”[9] The information uncovered by this study showed how the NRC was not able to properly evaluate radioactive waste on these sites. The NRC systematically failed to assess radioactive contamination using the agency’s own evaluation standards.

Ronson appears to have been one of the cases where the toxic waste was incorrectly evaluated by the NRC. This can be seen in a series of letters between Ronson and the NRC. In 1999, the NRC had taken five soil samples from the site and the agency asserted that “no violations were identified.”[10] According to the NRC’s evaluative standards for toxic waste, the Ronson site appeared to be in accordance with federal regulations. As it can be seen by the outcome of the site today, this was not accurate and it shows how shifting the cleanup to a federal agency may have led to systematic failures that can be attributed to bureaucratic mishaps. These bureaucratic mishaps may be due to inadequate department standards, but David M. Konisky’s article suggests that the socio-economic demographics of the area may be the underlying factors. Specifically, at the federal level the race and class of a community increase “disparities at other stages of the environmental regulatory enforcement process. These disparities may include fewer inspections and less stringent responses to instances of noncompliance.”[11] This shows that the outcome of the evaluation of the Ronson site didn’t derive from an evaluative fluke on the part of the NRC, but rather may have been a lack of enforcement due to the racial and class makeup of the site. It should be noted that in that same letter the NRC does state that the fact that there are no violations in the levels of radioactive waste it does not mean that Ronson has unrestricted use of the property yet. By that point, an investigation on the levels of radioactive waste was still being conducted by the NRC.

A year later the NRC’s inadequate assessment of the radioactive waste on the site would lead to Ronson being given unrestricted use of the property. This conclusion arose when looking into the NRC’s Final Status Survey of the Site released in 2000. In this document, the NRC had determined that “the release criteria for both thorium and external exposure rates have been met for the survey unit consisting of Buildings 1 through 5 and Area E.”[12] This document essentially had found that the radioactive materials found in the soil samples of the site were under the allowed limit dictated by the department. This shows the first failure of government at the federal level, where the inadequate assessment of the toxic waste allowed Ronson to continue with selling the land.

Local Failures

This same bureaucratic miscommunication occurred on the local level. The local government of Newark also failed to fully investigate the site. The issues first began when Ronson was in the process of selling the homes to REI developer in 2001. Before that could have been done REI had to go in front of a Newark planning board to answer questions about the site. The inadequate investigation of the site by the Newark government would go on to be another example of bureaucratic failure. For reasons that have not been made clear by city officials or the articles detailing the site, no one in the Newark planning board thought of reaching out to the DEP to inquire about the area or to even investigate the site by going through the city’s files. Had the DEP been contacted the planning board would have seen that “deed restrictions were placed on the land that clearly spells out what can be on there — parking and nonresidential uses only.”[13] As it was detailed in the Civil Action Complaint against Ronson, instead of investigating these issues city officials asked the REI engineer “whether the contamination at the Properties could meet residential standards, and REI’s environmental engineer responded that the radioactive component would meet the Department’s requirements”.[14] In the engineer’s statement, he stated that there were still radioactive elements in the site, but did not disclose the levels of the radioactive and toxic waste left behind on the site.[15] This is troubling when considering that even when asking the engineer that question, the planning board acknowledges that the area is going to go from industrial use to residential use. The fact that the land was under industrial use for so long should have made the planning board wary of the engineer’s overall statement. Ideally, this switch should have made the planning board want to verify the deed status of this area. All of the factors show how the planning board at the time was lazy and cared very little when it came to the Ronson investigation. The level of bureaucratic failure is shocking because the issues of the site had been made known to the city decades prior.

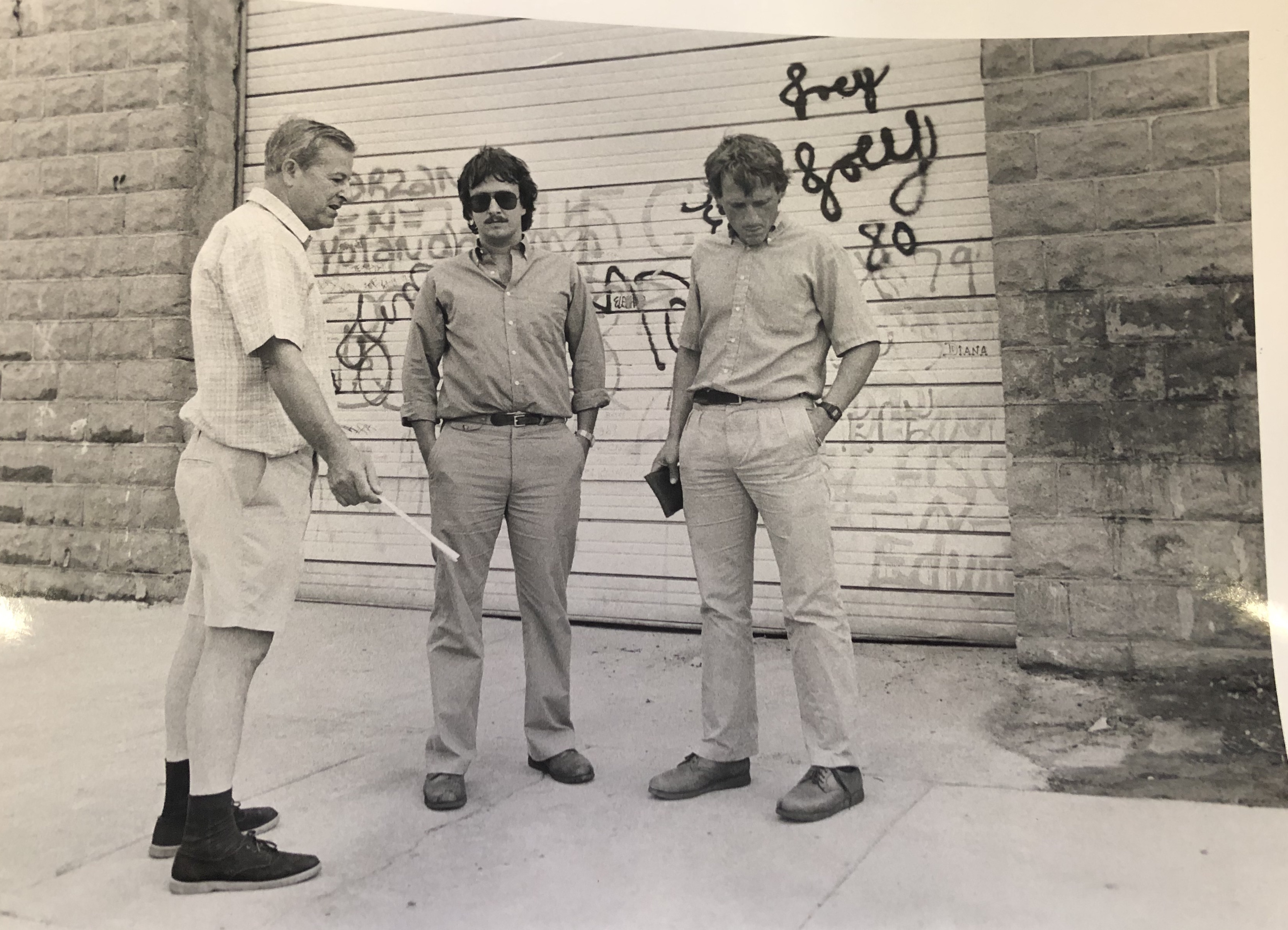

Newark’s planning board did not even try to communicate internally with the city’s departments that dealt with environmental issues. Had the planning board properly investigated within the city’s departments, as a bare minimum, houses in the area would have never been built. This is because Newark’s Department of Engineering and their Office of Environmental Services had been made aware of a toxic spill in the factory in 1984.[16] In a photo captured by the Star-Ledger, environmental specialists from both of these departments can be seen inside of the grounds of the factory observing the area where the spillage had taken place. This was an issue that was known in at least two different Newark departments. By Newark choosing to not do its proper research into the site, the site’s history, and the environmental hazards in them it shows how this issue was one rooted in the inadequacy of government agencies. The fact that the city’s departments had not even been approached for a second opinion on the site shows how the planning board did not care to properly investigate the issue. This shows how despite the fact that the radioactive materials in the site were on the city’s radar previously since no one tried to check or verify any information the site as we know it today was created. When thinking about how easily Newark could have avoided this Ronson site, there does not appear to be a logical or apparent reason for the city’s lack of investigating. It appears to just be a sign of carelessness and laziness.

This appears to be an example of Newark choosing not to do its job in investigating the site, expecting instead another government agency to do so. This is apparent in the Civil Action Complaint that denotes how the planning board “approved the subdivision application subject to approval by the Department and the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission”.[17] It seems that the planning board passed the buck up to the NRC, the same federal agency that did not properly evaluate the radioactive waste in the site. It can be deduced through these actions that the Newark planning board was too lazy to have their own investigation done, and instead expected the federal government to make the final decision on the site. Despite the fact that the issue was passed on to the federal government and that there was no official decision on the site the land was sold off and the homes were built.

Industrial to Residential

Many of these people are being sold these homes in the Ronson site with the purpose of emulating American values of suburbia and home ownership, but the homes are built on top of a toxic site. Under the context of environmental racism, it can be extrapolated that the ignoring of the possible risks of building the homes comes from an understanding that if there are any health-related repercussions people with economic, language and education restrictions are less likely to seek legal action. It may be these same factors of environmental degradation mixed with the working class and immigrant status of the Ironbound residents that makes the building of the homes appealing in the first place.

The image of the houses on Manufacturer’s Place was created with the purpose of showing the Ronson site in the modern day. This image was taken by Robert Sciarrino, a freelance photographer, who was working with NJ.com. The article in which this image was used was a story about the homes and the health hazards those occupying the homes endure. The photo was taken on February 27th, 2014 and when compared to the 1945 image it shows a dramatically different portrayal of Newark as a potentially residential area.

The second photograph is of the homes that were built on top of the remains of the second Ronson factory built in Newark that was located in Manufacturer’s Place. These same homes are currently undergoing EPA investigations as the chemicals that were used in the Ronson factory, primarily TCE, are contaminating the air in these homes. These two images represent the change of identity of Newark from a purely industrial area to an increasingly residential, suburbanized one.

The second image of the houses provides a different look into the identity of Newark and so suggests that there’s been an evolution in the perspective of the city. All four houses in the image are uniform in style and color. By making all of these houses that look the same the developer was able to create something that resembled a neighborhood. A possible goal would be to have an essence of suburbia in this industrialized city, to portray Newark as a place that’s home to more than just industry.

Another factor that becomes prevalent when both images are compared and contrasted is the sort of environment that the neighborhood in the second photo is trying to portray. Everything in this photo is still and gives off an essence of calmness that the image prior does not possess. Here all the cars are parked, there’s an absence of work/industry or any sort of human activity for that matter. This image shows a different side of Newark as a place where home ownership is possible, where a community can be created, and where the forces of the industry don’t have to be so apparent in everyday life.

Unfortunately, the calmness that the image seeks to portray is far from the truth. Although the uniformity of the houses imitates a suburban, calm environment that is still not the experience of many of the homeowners in this area. They still have to deal with the repercussions of the industry that was proudly boasted about in the prior image. This is a problem at large in the United States, where companies and their accomplishments are celebrated at the moment but those that are less fortunate have to deal with the consequences of that industry even decades later. The people who purchased these homes thought they’d be able to create a safe space for themselves and their families in the Ironbound, but even when the presence of industry isn’t evident Newark will always be a manufacturer’s place.

Environmental Racism?

These failures at the federal and local level can be analyzed on their own, or can be seen as the product of the demographic makeup of the Ironbound. The pursuit of profit is usually followed by the exploitation of working class people, and the Ironbound as an immigrant-majority area exemplifies the extent to which environmental racism and industrialization intersect. According to Luke W. Cole and Sheila R. Foster’s book From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement, environmental racism is typically when harmful or toxic facilities are placed in “communities that would offer the least resistance” to these institutions.[18] It has been found that “race was most often found to be the better predictor of exposure to environmental dangers” brought on by these facilities.[19] Roughly two out of three Ironbound residents are immigrants and the majority of the people there are working class, this demographic information suggests that environmental discrimination may have taken place.[20] Using this framework to analyze what led to the Ronson site is important, as it may give some clarity to the unexplained failures of the federal and local governments. In this section of the paper, the scientific data that will be used was provided by the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool.

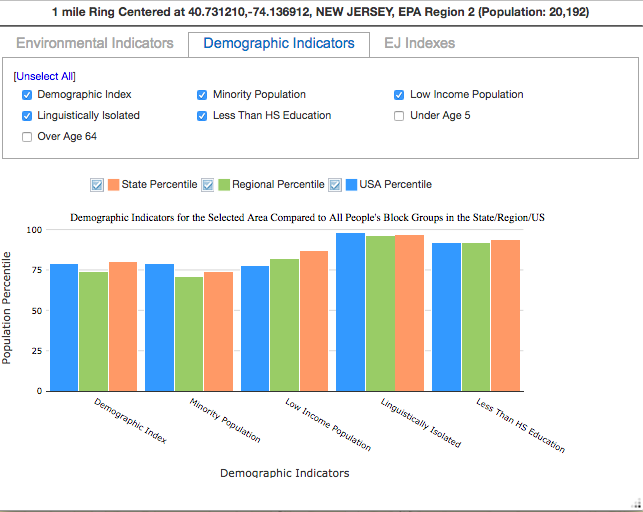

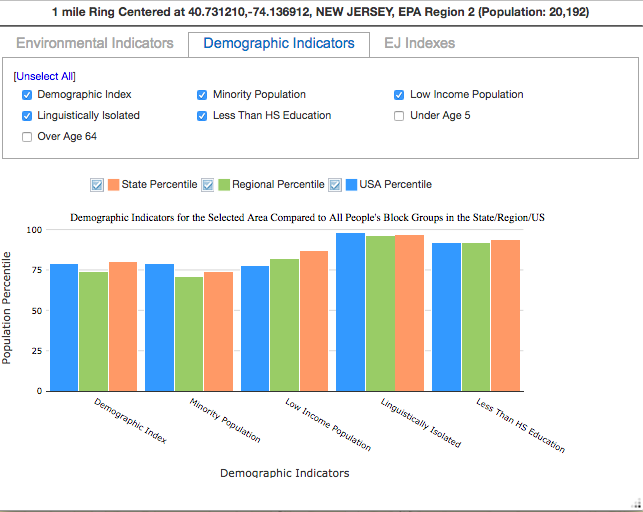

The Ronson site is marked by both vapor intrusion, primarily of the chemical Trichloroethylene (TCE), and groundwater contamination. The most relevant environmental factors with regards to the site are National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA) cancer risk and NATA respiratory hazard index. This is because understanding the overall health effects and toxin levels in terms of air pollution in the area can put into context the extent of environmental racism in the Ironbound, and thus in the Ronson site. This data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software. This software uses the environmental risks and demographic statistics of a specific area and compares those factors at the state, regional, and national level. Using the EJ Screen Software, a one mile buffer was created around the site. It showed that the people residing in the area are more affected than the average person in the state, region and country by these two environmental factors.

The first factor that will be analyzed is the NATA respiratory hazard index. The hazard index is the calculation of each hazard index’s “ratio of exposure concentration in the air to the health-based reference concentration set by EPA”.[21] All 20,192 people included in the buffer are in high percentile groups in both categories, but are the highest in the NATA respiratory hazard index (91 state percentile, 87 region percentile, and 93 national percentile). This data, as defined by the hazard index, suggests that there are more toxins in the air in this particular area that is allowed by the EPA. This can be deduced to be an effect of the overwhelming amount of industry surrounding the Ironbound, and how the effects on the environment of each facility is calculated individually as opposed to cumulatively.

The second environmental indicator being analyzed is the NATA cancer risk in the Ronson site’s area. The NATA cancer risk is defined as the “Lifetime cancer risk from inhalation of air toxics”.[22] The NATA respiratory hazard index affects the outcome of the NATA cancer risk of the people in the area. This cancer risk in the area was calculated to be in the 85 state percentile, 81 region percentile, and 85 national percentile. It should come at no surprise that because there is a higher amount of toxins in the air, these same air toxins are also increasing the risk of cancer of the people living there.

For access to the environmental and demographic data in these graphs, please click on the link below:

When trying to understand the possible factors that may have led to the Ronson site analyzing the demographic indicators of the area is key. The site is mostly populated by minority groups, which makeup 70% of the population. Consequentially, around 40% of that population is unable to speak English proficiently. This can be deduced to be an effect of the undocumented status of the majority of the population in the Ironbound.[23] These factors increase the likelihood that these populations will be marginalized at some point, especially when recalling the extensive influence that industries have had historically in Newark. These factors brought on by race are compounded by class where 51% of the population are in low-income households. It is typically the members of these communities that are “disenfranchised from most major societal institutions.”[24] This phenomenon of the disenfranchisement of these minority, low-income communities may be an explanation for why the government failed in the proper cleanup of the site. The challenges that the majority of the people in the Ironbound go through allow for some speculation as to why these two-family homes were built in such a polluted urban environment.

Environmental racism can’t be claimed with certainty to be the deciding factor in what led up to the creation of the site. The fact is that because the federal and local governments are refusing to take ownership over what led up to the creation of the site, the truth may never be known. The citizens of the Ironbound were failed by their governments every step of the way primarily through their inadequacy to do their job. This does appear to be changing for the better. In an effort to have more state control and thus more ownership over these radioactive and toxic waste sites New Jersey and the NRC came to an agreement. In 2009, the NRC delegated some oversight power to New Jersey. Allowing the state to have more direct control over the facilities that deal with radioactive elements and the way that these elements are cleaned up.[25] Hopefully, with these changes, future tragedies can be avoided and other New Jersey residents don’t ever have to deal with fear living in their own homes.

Notes

- Health Consultation. Page 19.

- This introduction is inspired by the stories of Ana Stival and her husband Fabiano DeSilva that were told on the article “Newark homes not so sweet with toxic vapors seeping inside” found on nj.com. The specific details being told in the introduction may not necessarily be attributed to Ana and Fabiano, but are instead generalizations made considering the socio-economic makeup of the Ironbound in Newark.

- “Ronson Lighters and Lewis Cigars, More Hot Items of the Past.”

- Health Consultation. Page 5.

- Civil Action Complaint: Jury Trial Demand. Page 2.

- Health Consultation. Page 5.

- “Regulation of Radioactive Materials.” United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission – Protecting People and the Environment.

- “Ronson Corporation Annual Report 10KSB/A.”

- United States, General Accounting Office. Nuclear Regulation: NRC’s Decommissioning Procedures and Criteria Needed to Be Strengthened : Report to the Chairman, Environmental Energy, and Natural Resources Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives.

- “INSPECTION NO. 040-08843/99-003.” Robert R. Bellamy to Daryl Holcomb. February 11, 2000.

- Konisky, David M. “Inequities in Enforcement? Environmental Justice and Government Performance.” Page 105.

- McLaren/Hart Inc. Report of the Final Status Buildings 1-5 Soils at the Site

- Carter, Barry. “Newark Homes Not so Sweet with Toxic Vapors Seeping inside.”

- Civil Action Complaint: Jury Trial Demand. Page 11.

- Civil Action Complaint: Jury Trial Demand. Page 11.

- Lawson, Jennifer. Newark-Ronson. Newark, 20 July 1984.

- Civil Action Complaint: Jury Trial Demand. Page 11.

- Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. Page 3.

- Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. Page 55.

- “Our Community.” ICC

- “Glossary of EJSCREEN Terms.” EPA. August 02, 2017.

- “Glossary of EJSCREEN Terms.” EPA. August 02, 2017.

- “Our Community.” ICC

- Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. Page 33.

- “Radioactive Materials Program.”

Bibliography

- “Glossary of EJSCREEN Terms.” EPA. August 02, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/glossary- ejscreen-terms.

“INSPECTION NO. 040-08843/99-003.” Letter. Robert R. Bellamy to Daryl Holcomb. February 11,2000. 475 Allendale Road, King of Prussia, PA. https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0036/ML003688640.pdf - “Our Community.” ICC. https://www.ironboundcc.org/who-is-icc.

- “Radioactive Materials Program.” NJDEP-Bureau of Environmental Radiation. https:// http://www.state.nj.us/dep/rpp/rms/rmsagree-1.htm.

- “Regulation of Radioactive Materials.” United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission – Protecting People and the Environment. https://www.nrc.gov/about-nrc/radiation/protects-you/reg-matls.html.

- “Ronson Corporation Annual Report 10KSB/A.” Ronson Corporation Annual Report 10KSB/A. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/84919/000091431700000250/0000914317-00-000250-d1.html.

- Carter, Barry. “Newark Homes Not so Sweet with Toxic Vapors Seeping inside.” Nj.com. April 13, 2014. https://www.nj.com/essex/2014/04/newark_homes_not_so_sweet_with_toxic_vapors_seeping_inside.html.

- Civil Action Complaint: Jury Trial Demand, 1-28 (Superior Court of New Jersey August 01, 2018). nj.gov/oag/newsreleases18/Ronson.pdf.

- Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. New York: New York Univ. Press, 2001.

- Konisky, David M. “Inequities in Enforcement? Environmental Justice and Government Performance.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28, no. 1 (2009): 102–121.

- Lawson, Jennifer. Newark-Ronson. Newark, 20 July 1984. (Left to right) Anthony Sikora of Newark; Walter S. Janicek, senior environmental specialist, both with the Newark Department of Engineering, Office of Environmental Services, stand outside a Ronson warehouse at 43 Manufacturer’s Place, Newark, discussing the hazardous waste which as spilled where they are standing. (Sikora lives on the street behind the warehouse).

- United States, General Accounting Office. Nuclear Regulation: NRC’s Decommissioning Procedures and Criteria Needed to Be Strengthened : Report to the Chairman, Environmental Energy, and Natural Resources Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives. U.S. General Accounting Office, 1989. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112033991917.

- McLaren/Hart Inc. Report of the Final Status Buildings 1-5 Soils at the Site, Newark, Prepared by: 25 Independence Blvd Warren, NJ 07059 Inc. 5900 Landerbrook Dr. Cleveland, OH 44124 Preparedfor: Prometcor, Inc Corporate Park III Campus Drive Somerset, NJ 08875 Survey for and Area E Promet. PDF.

Primary Sources:

Source 1

Title: Public Health Implications of Site-Related Indoor Air Exposures

Location: Online source- https://www.state.nj.us/health/ceohs/documents/eohap/haz_sites/essex/newark/ronsonmetals/rm_indoor_air_exposures_hc_jul2015.pdf

This is a government report that gives background information on the Ronson site that primarily details the health related risks and potential pollutants in the site. It does give some background on the site and how the houses came to be built there, but it serves primarily as a health consultation evaluating the effects of the different chemicals infiltrating the ground water there. This document would be used to assess the risks that the residents in the site are exposed to. On page 3, on the 3rd conclusion it states that although some homes have sub-slabs systems installed (that block the pollutants from entering the house) this is not a permanent solution, and that future, more permanent improvements would be needed.

Source 2

Title: Civil Acton Complaint: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection v. RCLC (Ronson) Inc.

Location: Online source- https://nj.gov/oag/newsreleases18/Ronson.pdf

This is a lawsuit from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection against Ronson and 10 of their employees. This document serves as a tool to recognize the series of events that led to this site be turned into a residential area. It details the extent of the pollution, the ways in which it was cleaned up, and the process by which the deed to the land was sold off to REI (a development company). This source provides a clearer narrative with regards to how the site came to be, while also showing how REI is partly responsible along with Ronson for having lied to the planning board about the contamination (paragraphs 47 and 48) and building houses without receiving full consent from the city. This document would be used for the background and legal information surrounding the site, as well as for the information with regards to the environmental impacts left on the area.

Source 3

Title: Newark homes not so sweet with toxic vapors seeping inside

Location: Online source- https://www.nj.com/essex/2014/04/newark_homes_not_so_sweet_with_toxic_vapors_seeping_inside.html

This article talks about the modern-day state of the site and the ways in which the citizens of Newark were failed by their local and state agencies. This source provides more context in the ways that state and local agencies did not appropriately communicate and are now pointing fingers as to who is to blame for this site. It details how the DEP did not even know up until they visited the site in 2012 that there were houses built on the site, as “the deed restriction said parking lots and nonresidential only”. This source will provide a different angle when it comes to decided the parties responsible for the site. It ties in Ronson, REI, the DEP, and Newark’s government into the analysis of the site.

Secondary Sources:

Source 1

“Ronson Corporation Annual Report 10KSB/A.” Ronson Corporation Annual Report 10KSB/A. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/84919/000091431700000250/0000914317-00-000250-d1.html.

This source is a quarterly report done on June 30, 2000, to the Securities and Exchange Commision. This source breaks down the ste on Manufacturer’s Place and provides insight into the role the Nuclear Regulatory Commission played in the creation of the site. Specifically, it will be used to put into context the different government agencies involved in the site. This source also provides more information into the outcome of the cleanup from Ronson’s part, as well as information about the process by which the properties were sold off to the home developer.

Source 2

United States, General Accounting Office. Nuclear Regulation: NRC’s Decommissioning Procedures and Criteria Needed to Be Strengthened : Report to the Chairman, Environmental Energy, and Natural Resources Subcommittee, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives. U.S. General Accounting Office, 1989. http:// hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112033991917.

This is a government report on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) that was created for the House of Representatives in 1989. This source will be useful in the analysis of the federal government’s failures on the Ronson site. A specific point that will be stressed through the use of this source is how the NRC had inadequate standards when it came to assessing radioactive elements left on industrial sites. This source shows how the Ronson site may have been caused by the federal government’s inadequacies.

Source 3

Konisky, David M. “Inequities in Enforcement? Environmental Justice and Government Performance.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28, no. 1 (2009): 102–121.

This source is a journal article about studying the ways that state governments fail to enforce environmental protections for low-income, minorities of color as opposed to white, affluent communities. This article would be useful because it would show how low income communities are not properly protected by state governments across the United States when it comes to environmental issues. It would tie into the Ronson case because there was such a disconnect between the local government and the state government which inevitably led to the building of homes in the site. Some of the common factors between what is being experienced at the state level and then what was experienced in the Ronson site is a lack of inspections and a lack of response to calls for site clean up. It shows how this issue isn’t just occurring in the Ironbound, but rather on the national level.

Image Analysis:

Newark has always been known as an industrial city, a place defined by manufacturing and the boom of development. The original Ronson factory is a testament to this perspective on Newark, and the homes that will eventually be built on top of that torn down factory will attempt to refute that. The first photograph is of the Ronson Art Metal Works factory that resided in Aronson Square. The second photograph is of the homes that were built on top of the remains of the second Ronson factory built in Newark that was located in Manufacturer’s Place. These same homes are recurrently undergoing EPA investigations as the chemicals that were used in the Ronson factory, primarily trichloroethylene or TCE for short, are contaminating the air in these homes. These two images represent the change of identity of Newark from a purely industrial area to an increasingly residential, suburbanized one.

The image of the Ronson factory in Aronson Square was taken in 1945. The photographer that created the image is not known, but the photo is archived in the Newark Public Library’s online webpage detailing Newark history. The website details the importance of the Louis V. Aronson, the founder of Ronson, as “one of Newark’s greatest industrial leaders and philanthropists”. This photo in conjunction with the source material it supports shows the extent to which Aronson and Ronson became influential identities in Newark. The image served to show to a newer generation and even the current Newark generation at the time the sort of power these entities had over the city, going as far as having a factory running in a square named after the founder of said company. The second image of the houses on Manufacturer’s Place have a different purpose. They were taken by Robert Sciarrino, a freelance photographer, who was working with NJ.com writing a story on the homes and the health hazards those occupying the homes endure. The photo was taken on February 27th, 2014 and when compared to the 1945 image it shows a dramatically different portrayal of Newark as a potentially residential area.

The first image displays a busy street in front of the Ronson factory, with cars going in all sorts of directions. Choosing this particular time in the day to take the photo when there are so many cars passing by the factory can be assumed to have been a deliberate choice to affect how the factory is perceived. Having the traffic be at the center of the image makes Aronson Square and the factory itself seem like prominent entities in Newark. It elevates the status of the factory in the city, making it seem like an integral part of it. One potential interpretation is that the photo served to show the Ronson factory as a beacon of industrial prowess in Newark, becoming a representation of the city of Newark as a place of industry, manufacturing, and opportunity.

This theory is emphasized by the appearance of the Ronson factory itself when compared to the other buildings surrounding it. The first photo is black and white, as it was taken in 1945, and the most notable features with a discernible color difference are the banners promoting the factory. Two of them are of a dark color that appears black in the photograph, and the white banner appears behind those two. All three banners were placed there to emphasize Ronson’s presence in the photo and area as a whole. This becomes even more significant when observing how there are no other discernible buildings or landmarks in the photo. By not showing or having any other notable buildings in the photo the presence of Ronson in Newark is highlighted. This is done to place Ronson at the center of Newark and therefore it’s symbolically at the center of industry.

The second image of the houses provides a different look into the identity of Newark and so suggests that there’s been an evolution in the perspective of the city. All four houses in the image are uniform in style and color. By making all of these houses that look the same the developer was able to create something that resembled a neighborhood. A possible goal would be to have an essence of suburbia in this industrialized city, to portray Newark as a place that’s home to more than just industry.

Another factor that becomes prevalent when both images are compared and contrasted is the sort of environment that the neighborhood in the second photo is trying to portray. Everything in this photo is still and gives off an essence of calmness that the image prior does not possess. Here all the cars are parked, there’s an absence of work/industry or any sort of human activity for that matter. This image shows a different side of Newark as a place where home ownership is possible, where a community can be created, and where the forces of the industry don’t have to be so apparent in everyday life.

Unfortunately what the image seeks to portray is far from the truth. Although the uniformity of the houses imitates a suburban, calm environment that is still not the experience of many of the homeowners in this area. They still have to deal with the repercussions of the industry that was proudly boasted about in the prior image. This is a problem at large in the United States, where companies and their accomplishments are celebrated at the moment but those that are less fortunate have to deal with the consequences of that industry even decades later. The people who purchased these homes thought they’d be able to create a safe space for themselves and their families in the Ironbound, but even when the presence of industry isn’t evident Newark will always be a manufacturer’s place.

Data Analysis:

The Ronson site is marked by both vapor intrusion, primarily of the chemical Trichloroethylene (TCE), and groundwater contamination. The most relevant environmental factors with regards to the site are National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA) cancer risk and NATA respiratory hazard index. This is because understanding the overall health effects and toxin levels in terms of air pollution in the area can put into context the extent of environmental racism in the Ironbound, and thus in the Ronson site. This data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software. This software uses the environmental risks and demographic statistics of a specific area and compares those factors at the state, regional, and national level. Using the EJ Screen Software, a one mile buffer was created around the site. It showed that the people residing in the area are more affected than the average person in the state, region and country by these two environmental factors.

The first factor that will be analyzed is the NATA respiratory hazard index. The hazard index is the calculation of each hazard index’s “ratio of exposure concentration in the air to the health-based reference concentration set by EPA”.1 All 20,192 people included in the buffer are in high percentile groups in both categories, but are the highest in the NATA respiratory hazard index (91 state percentile, 87 region percentile, and 93 national percentile). This data, as defined by the hazard index, suggests that there are more toxins in the air in this particular area that is allowed by the EPA. This can be deduced to be an effect of the overwhelming amount of industry surrounding the Ironbound, and how the effects on the environment of each facility is calculated individually as opposed to cumulatively.

The second environmental indicator being analyzed is the NATA cancer risk in the Ronson site’s area. The NATA cancer risk is defined as the “Lifetime cancer risk from inhalation of air toxics”.2 The NATA respiratory hazard index affects the outcome of the NATA cancer risk of the people in the area. This cancer risk in the area was calculated to be in the 85 state percentile, 81 region percentile, and 85 national percentile. It should come at no surprise that because there is a higher amount of toxins in the air, these same air toxins are also increasing the risk of cancer of the people living there.

For access to the environmental and demographic data in these graphs, please click on the link below:

When trying to understand the possible factors that may have led to the Ronson site analyzing the demographic indicators of the area is key. The site is mostly populated by minority groups, which makeup 70% of the population. Consequentially, around 40% of that population is unable to speak English proficiently. This can be deduced to be an effect of the undocumented status of the majority of the population in the Ironbound.3 These factors increase the likelihood that these populations will be marginalized at some point, especially when recalling the extensive influence that industries have had historically in Newark. These factors brought on by race are compounded by class where 51% of the population are in low-income households. It is typically the members of these communities that are “disenfranchised from most major societal institutions.”4 This phenomenon of the disenfranchisement of these minority, low-income communities may be an explanation for why the government failed in the proper cleanup of the site. The challenges that the majority of the people in the Ironbound go through allow for some speculation as to why these two-family homes were built in such a polluted urban environment.

Notes

- “Glossary of EJSCREEN Terms.” EPA. August 02, 2017.

- “Our Community.” ICC

- Cole, Luke W., and Sheila R. Foster. From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. Page 33.

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

For my project, I conducted a video essay about Ronson inc. and it’s legacy in Newark from 1926 until the present day. The focus of the video is one of its factories in Manufacturer’s Place located in the Ironbound. This factory repeatedly had hazardous waste spills, and yet it was sold off to a developer who created houses on top of this area. The video story seeks to follow the timeline of these events and the factors that may have caused the waste site in the first place.