Proposed Sewer Plant near Musconetcong River could have negative environmental impacts and locals are demanding alternatives.

by J. Haug

Site Description:

The sewer plant is only part of a proposed housing development project on Valley Road in Hampton Borough, NJ. The plan was proposed 40 years ago and has received backlash, but after a recent court settlement the project was allowed to continue. With little the residents can do to stop it now, the goal is to mitigate any damage done by this project since locals have voiced their concerns. How would a sewer treatment plant affect the water supply so close to the Musconetcong River, and what are other, safer options if this is unavoidable? Contaminating the proposed area could have lasting effects on locals drinking water and the river quality, which could result in untold environmental damage if something isn’t done.

Final Report:

Introduction

We heard the whistle, and we were off; 20 little kids all chased the same soccer ball around the fields of Hampton Borough Park with absolutely zero team coordination. I was on the orange team, back when we were too little to know what to do, and just happy to participate. After the games were over and ‘both teams won,’ the families gathered at the playground/seating area letting all the kids play while the parents made lunch and relaxed. There were steep, grassy hills between the fields and playgrounds and Musconetcong River that ran beside the park, which made for many memories rolling down the hills and playing on the river’s edge. The river was also a great spot for trout and lots of people were always there, fishing all summer. It has been called “one of New Jersey’s most important trout waters.”[1] There are no plans [yet] to change or do anything to the park directly, thankfully. It will remain a community treasure, however many locals are unaware or unable to do anything about the 40-year-old plans going on upstream.

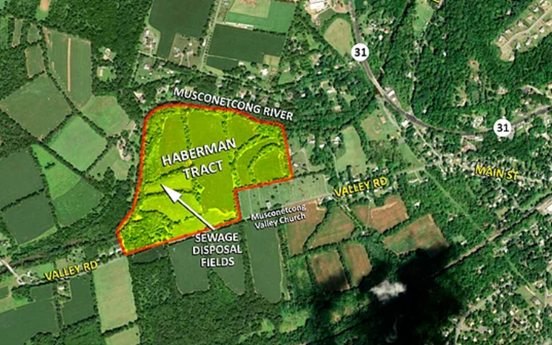

Back in 1981, a property just up the road, was bought by a New York City developer, Jacob Haberman, who planned to have a massive 144-acre residential complex built. This was immediately concerning because the river runs directly adjacent to the planned site (Figure 1) and speculation began regarding what it could mean for the area. The plans were soon halted, and the town of Hampton went to court with Haberman over the many concerns. After years of negotiation, in 2015 a settlement was finally reached that allowed construction to begin.[2] The final plans, however, included a ground water disposal field as part of the sewer system to be built for the complex that has become the new focus of advocacy groups after the settlement. The location is dangerously close to the bank of the Musconetcong River which poses an enormous ecological and environmental threat in a myriad of ways.[3] To locals it means possibly introducing sewer runoff into the drinking supply and river; parents that now have to worry about their kid’s health near the Musconetcong, and also its negative effects on the local trout ecology.

Considering the whole sequence of events simply leaves the residents of Hampton Borough feeling exhausted. At first, they’re asking “why this location?” Then after such a long court dispute, “how did Hampton lose? And why did it take so long?” This would be important to know in the future for either upcoming development projects or so other local governments can learn how to stop similar situations from happening. More currently, we want to know how to mitigate the potential pollution this sewage system will cause now that the plan is in action today. The health implications this could cause for residents is more important since this concerns the future of the area, not to forget it is still important to learn from this case’s history. These will all be covered and answered throughout this report by analyzing the history and geography of the town of Hampton Borough, the governments initiative to clean up our nation’s waters (including the Musconetcong) with things such as the Clean Water Act, and how these come together in and out of the court room to help the people of Hampton mitigate any environmental damage to come.

Case History

The first mentioning of these plans in the court system was on the 30th of September 1981. The building plans have certainly had a fair share of revisions and updates since then, making it look nothing like where it started. Jacob Haberman proposed a plan to build on two lots: Block 23, Lot 1 (the north tract) and Block 24, Lot 2 (south), totaling 144 acres. After 4 years, the parties reached a settlement agreement with a few minor details under appeal; nothing concerning enough to stop the development. In 1988 however, “The Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act, N.J.S.A. 13:20-1, et seq., was adopted” which turned the southern tract (Lot 2) into a preservation zone, limiting development heavily and requiring Haberman to only develop on Lot 1. In 2010, Haberman noted several complaints to the court that impeded or restrained his progress, citing multiple DEP regulations and federal designation of the Musconetcong River as a wild and scenic river, under the Clean Water Act (1998).[4] The court documents and evidence presented at multiple hearings was collected and amended to the final court settlement (found on the official website of the Hampton Borough Clerk’s office under Exhibit’s A-E). There were plans to proceed with development, but a motion couldn’t be passed, despite a few years of cooperation between the plaintiff and defendant.

That was until in 2015, the retired Judge Eugene D. Serpentelli submitted his letter of approval. Judge Serpentelli became involved around 2012 and worked for a few years with both parties to gain a “comprehensive understanding of the parties concerns and positions as well as a clearer picture of many of the issues of law” (Exhibit D, pp 4). His mediation reached a settlement that was argued by both parties and the community after many fairness hearings in 2015 (May 29th, June 10th, 11th, 19th). Lots of evidence at these hearings was brought up by community members and advocate groups in opposition of the settlement. This included the fact that the area “is a direct hydraulic connection between the ground water on this site and the Musconetcong River which is protected by the N.J. DEP.” The community was at a loss on October 25th, 2015, when the court agreed on the settlement and Jacob Haberman won, allowing for development to proceed (Hampton Borough clerk).

A massive part of the groundwater supply and ecology issue has to do with the local geography near the park and borough area. The town of Hampton sits at the bottom of a long hill; even highway 31 veers out to the right, around the mountain that is just south of Hampton on this map. A map taken from the United States Geological Survey (USGS, 2016) shows this elevation difference. Looking closer, the number values across the town start at roughly 700 – 800 feet near the location of the post office which marks a sort of border, on the edge of town, and go down to 340 ft. by the river. This means there is an almost 400 ft. elevation difference across the town which contributes to the flooding and shallow groundwater issue by the development site.

The Governments Initiatives

The reason any of this is important comes from the governments initiatives to clean our nation’s waters, but not after multiple attempts and figuring out a strategy that works for all. The history of the government’s involvement begins with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968), however this only “protects less than ¼ of one percent of the United States’ River miles,” according to Alan Hunt, et. Al., (who is also a director of the Musconetcong Watershed Association which becomes involved later). In a paper written by him and colleagues called “Picking up where the TMDL leaves off,” the total maximum daily limits (TMDL’s) of pollution were set, however this simply wasn’t enough as it made very clear that reducing pollution to the TMDLs was “extremely difficult.” This is made clearer when the designation of Outstanding Wild and Scenic Rivers came about, since it added many more rivers to the protection program (44% of the Rivers in the Nation), however this meant that the remaining majority didn’t receive the same kind of care. Hunt describes the conflict of water quality well with the one sentence: “The jurisdictional and institutional divisions between water quality regulators and river managers results in conflicting mandates and underlying weakness in the durable protection of WSRs.” This is a collaborative effort that is [mostly] improved with the enactment of the Clean Waters Act.[5]

The Clean waters Act (1972; formerly known as the Federal Water Pollution Control Act) was implemented to form “community-based watershed partnership” since at the federal level, it was clear the efforts weren’t being translated down to local community members and their scenic rivers. In the 21st century, efforts to clean our waters were set back due to conflicting political priorities from the Clinton and Bush administrations, but a willing and helpful National Parks service helped these watershed movements grow over the past few decades. The “NPS delegated day-to-day river management to local organization” which in my opinion has been the most effective change to water quality management in the United States and has had a profound impact on protecting our beautiful wildlife, which seems to loom in the shadows of most political issues we hear today.

This Act was of course applied across the country, however the paper by Hunt aims its study of the implementation of these government acts on the Musconetcong River, a tributary of the Delaware that runs south-west through north-western New Jersey; and of course the nearby river to the Haberman development plans. One of the many local watershed organizations started by the Clean Waters Act includes the Musconetcong Watershed Association (MWA), of which Alan Hunt is a director. These associations created by the Clean Waters Act were given outlines of detailed steps in the report to help water quality efforts at the ground level, which is did. The Musconetcong River even had data to show it exceeded the TMDL goal of reducing bacteria by 93% (the MWA achieved 95% decontamination), as stated by the NJ DEP’s “Total Maximum Daily Loads for Fecal Coliform.” These government initiatives, have since proven their worth across the country, but in the case of the Class-1 protected river of the Musconetcong, the local community has really come together to protect such a regional gem. Many people, across the country even, don’t believe NJ has beauty. Most people that travel through live by NYC which has been developed and overcrowded, making for a not very pretty scene as you drive by. When in fact, there are massive areas of forests and fields with their beauty in the southern pine barrens and western rivers/streams.

Today’s Plans

The proposed groundwater discharge sewer system that needs to be built to support the new housing is the problem with the updated plans after the court case granted permission to continue development. In reality, there were a total of 8 environmental concerns discussed in Serpentelli’s letter that all were discredited, fairly or not. Many of the issues dealt with permits needing to be obtained, conservation zones, and areas of “prime agricultural soil” that were mediated by Serpentelli and both parties so that the new plans were within these ordinances.[6] The local court was now satisfied, but the public still argued against development with essentially the sole purpose of saving the river and local ecology. The environmental concerns were dismissed with the remediation of the plans; however, the public still aren’t happy. The developers make it clear in the court documents of their plans that the water being discharged into the field will be scrubbed of contaminants from the sewer runoff, but the potential for either lackadaisical cleaning of the sewer water or sewer system runoff during severe flooding should be enough to stop it. Essentially, the local government was mediating the case as a ‘quantitative checklist’ to ensure all legal bases were covered, when the community was bringing up more qualitative concerns that the court simply turned its head away from.

A paper by Marco van Bijnen, et al., titled “Quantitative impact assessment of sewer conditions on Health Risk” describes the probability of contaminants impacting our health with respect to a community’s sewer system and possible overflow that occurs during flooding. It is important to describe briefly how most urban sewer systems work. Today, most towns have what is called a Combined Sewer Systems which merges the water that comes from your house with water runoff from the environment and sends the combined stream to the wastewater treatment plant. The only times this can cause problems is during sever flooding. This is because, like any water/chemical treatment process, the plants are designed with a maximum flow rate intake. It’s simply impossible to design a system with an endless intake value, and so when the amount of rushing water is too high, the combined sewer stream has no where to go other than overflow the drains and return to the streets, and therefore environment.[7] This is the type of contamination that the people of Hampton are worried about effecting their drinking water supply or their river water. To anyone, this idea is convulsing. Not to mention, the area the developer plans to build on is already one where frequent flooding occurs.

What now?

Trying to stop construction altogether is now futile. Plans have not started on site as of yet, but there is no more red tape to stop the developers now. To answer a question from earlier, cases like this are allowed to go unchecked (or at least with very minimal pushback) because many, like myself, either didn’t know about the plans to begin with, or don’t know where to start getting involved. This can be a daunting task for one person, to stand up to any corporation with legal or environmental reasons to stop their progress.

First and foremost, some of the many important organizations mentioned here are quite easy to be a part of. The MWA has meetings literally down the road from the development in their office. State and local governments and municipalities are hold open meetings frequently, it’s simply a matter of knowing. There were many mentions and notifications of each and every fairness hearing (all 6 dates), but when the time came, a total of maybe 10 community members were there to voice their opinion. This case would be in a very different position if there were 100 people demanding change.

These may seem like simple lessons that everyone has heard before: “Get involved”, “vote”, “go to public forums.” However, these are the backbone of local government. There is no government without the people, and the biggest lesson to take away from the case of Hampton are the quotes above, as cliché as they may sound. Lobbying politicians is an equally important task as evident in the enactment and enforcement of the Clean Waters Act. If the presidential administrations mentioned in the past showed a lack of initiative before, then it could happen again. It was the formation of these smaller community-run groups that do the dirty work, and fight for what the developers and politicians can’t see.

For anyone or town going through a similar problem with an environmental injustice being threatened by big developers, don’t let the case of Hampton Borough happen again. More could be done, and sooner rather than later. These are even just the basic of community involvement. Even further steps can be taken to get more action done. While official mediation efforts and government studies can be sound judicially, this proves that the concerns on the ground were not being met, but with a little outreach, that can change.

[1] A quote from the NJDEP Green Acres plan used in Hunt’s “Picking up where the TMDL leaves off” describes the importance of the Musconetcong.

[2] Taken from the transcript of the court case where MWA members included a detailed presentation about the history and environmental impacts of the site.

[3] A blog post from the Musconetcong Watershed Association included a map and details the ecological impact of the groundwater discharge sewer system, https://www.musconetcong.org/community-advocates.

[4] Court documents taken from Haberman vs. Hampton Borough court appearances and evidence attached (See Exhibit’s A-E. http://www.hamptonboro.org under “Forms & Documents”.

[5] “Picking up where the TMDL leaves off” by Alan Hunt, et al., describes in detail the role and history the Gov. has played in keeping our waters clean.

[6] An NJ.com article, as well as the court documents, also notes that there was a dispute over the percentage of “affordable housing” that should be accommodated that came with its own set of legal battles, however this didn’t pertain to the environmental impact.

[7] Cities can have different types of infrastructure to deal with overflow, however the plans in Hampton only include a small collection zone with an area of only 20 x 20 m2 which many have criticized for not being nearly enough (Hampton Borough Clerk).

Primary Sources:

- New Jersey Highlands Coalition. Jacob Haberman v. Hampton Borough. 2 Nov. 2015.

This is a transcript from the Haberman v. Hampton Fairness hearing from the Highlands Coalition (collection of official organization aimed at preserving New Jersey’s water and other natural resources).

This court hearing will be useful because it recounts actual public locals/residents and their concerns the project will bring with it; as well as data to back possible solutions to aid in solving the environmental issues.

- Hunt, Alan. “Community Advocates.” Musconetcong Watershed Association, 2020, https://www.musconetcong.org/community-advocates.

This is a website post and presentation made by the Musconetcong Watershed Association, a local organization working very closely with others in opposition of the project, that covers the site history and their opinion and supporting facts.

The history and imagery are important to visualize the scale of the project and understand the proposed plan and it’s possible environmental impact.

- United States, Congress, Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance. Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1972, pp. 816–903.

Bill Clinton and his administration released his Sustainable America report which prompted the Clean Water Action Plan by the EPA in 1998, as an amendment to the original “Federal Water Pollution Control Act” from 1972.

The official federal document will be useful to understand the requirements put in place that prompted the preservation of our nations Nature and wildlife, including our rivers and water quality due to pollution which will apply to the argument and the case of the Musconetcong.

- United States, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Division of Watershed Management. Total Maximum Daily Loads for Fecal Coliform to Address 28 Streams in the Northwest Water Region, NJ G.P.O., 2003, pp. 1–78.

The Total Maximum Daily Load’s (TMDL) of fecal coliform are the quantitative values the Clean Water Act put in place for pollution levels in out nations rivers/water, determined and published by the NJ Department of Environmental Protection. The values described pertain to each river in the selected region and its qualities contributing to river fecal pollution, including the Musconetcong River.

- Hampton Borough Clerk’s Office. Jacob Haberman v. The Council of The Borough of Hampton. May 2016.

Can also be found online at http://www.Hamptonboro.org under the “forms & documents” tab.

This source is a very long document that contains the detailed history of the Jacob Haberman vs. Borough of Hampton court case regarding the development plan and operation of the housing complex from 1981. Exhibit’s A-E are each separate documents, litigation settlements, Judge letters of approval, and court amendments that were described in detail at various court dates. This official document gives great insight to not only the judicial system and how the case is handled, but also the building and development plans and how they were forced to undergo changes along the way.

This all started on September 30, 1981; the first filing date of this case. The total amount of land initially proposed to be developed was in two different lots across Valley Road from each other, Lot 2 (the south side of the street) and Lot 1 (north). After some years of arguing against each other after the town pointed out conflicts in planning and other development procedures, in 1988 “The Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act, N.J.S.A. 13:20-1, et seq., was adopted. That Act placed Block 24, Lot 2 was in the [new] preservation zone” which would limit development severely. This forced Haberman to redesign his plans and a new 1988 settlement reached would only include building on the northern Lot 1. It goes on to point out a few more key arguments made by supporters against the project (like the Musconetcong Watershed Association). Alan Hunt, the president of the MWA, stated “There is a direct hydraulic connection between the ground water on this site and the Musconetcong River which is protected by the N.J. DEP surface water quality standards” in opposition to the development. The multitude of facts and quotes from the courtroom directly will help paint a picture of how this case was judicially handled and will provide great evidence to support the argument against the development.

Secondary Sources:

- Askins, William. “Oystering and Equality: Nineteenth Century Cultural Resistance in Sandy Ground, Staten Island, New York.” Anthropology of Work Review, vol. 12, no. 2, 1991, pp. 7-13., https://doi.org/10.1525/awr.1991.12.2.7.

This is an article about how the area of Sandy Ground maintained their community of “relative equality” and how it was impacted with the typhoid outbreak and coinciding Jim Crow movement.

This article describes in detail the racial history of the area since its establishment near the late 1840’s. Following a small community of African American’s known as the “Freemen,” the community had become a multi-ethnic village of the African American and native white population. The community even thrived with the reconstruction period and booming oyster industry, but not without many cases of resistance over the years. Stress only rose with the end of the industry following the typhoid outbreak and Jim Crow movement. A once diverse and accepting area was under ideological assault and this article will be a great source to describe and use this history when talking about today’s oyster project.

- Kadinsky, Sergey. “Crooke’s Point, Great Kills Park.” Forgotten New York, 21 Dec. 2018, https://forgotten-ny.com/2018/12/crookes-point-great-kills-park/.

This source is a website article about the geographical history of the Harbor and more specifically the transformation of Crooke’s point to create the Great Kills Harbor site today.

The article will provide a useful geographic background of the area because it’s undergone quite a change since the area was settled and industrialized with the oyster industry. The article provides helpful visuals to show how the point used to be an island/sandbar disconnected from Staten Island. In an effort to aid with the 6 ft tides and high current the shoreline faced, the area was filled in to connect the island, forming the point and harbor today. The article also points out the tough environmental history the point has had. During its creation, large sections of land were filled in not with sand, but with trash from landfills which afterward caused an area of radiation to be found after radium was apparently dumped below ground. This is still causing problems for the public and parks association that runs the Great Kills Park as there are still areas blocked off to the public.

- Ricardson, Safari. “Finding Freedom Through Oysters in 19th Century New York (Part Two).” History News, NC State University, 22 Feb. 2019, https://history.news.chass.ncsu.edu/2019/02/22/finding-freedom-through-oysters-in-19th-century-new-york-part-two/.

This source is an article that describes the history of the Oyster industry in Staten Island and the first “Freeman” African Americans that established the area and industry after the civil war.

Safari Richardson recounts the stories of two well-known free African Americans and the history of the area and industry surrounding the oysters of the harbor. The background information/history will be a great source to better “paint the picture” of what the area was like and how it came to be. The area was settled by a group called the “Freemen” from the south before the end of slavery. Their job being to harvest the oysters in the harbor for food and other materials. Shortly after, they were freed and remained in the area, however very poor and with not much help from others at the time, oystering became the way of living for many. Understanding the past racial injustices will be important cases and lessons we can hopefully see improved with the oyster project(s) of today.