Oyster Occupation: A Look Into The Oyster Industry In Raritan Bay

by Erik Aleksanyan

Site Description:

Bordering New York and New Jersey is a small river named the Arthur Kill. Pre 1900’s the river was teeming with wild oyster beds ready to be caught and enjoyed by locals. In the beginning of the 1900’s this population started to decline. The recovery of these beds is slow but steady as people working on both sides of the river attempt to rebuild this once full river. Throughout this long time period of prosperity to decline to recovery it is questioned as to who can be responsible for the devastation. More importantly how did the actions of the devastators affect communities which used the beds as their main source of income. It is also important to wonder how the violators reacted to being reprimanded as well as what their reasons for destruction were. With constant waterbed pollution across the world it is important to look to recognize the violators. The oysters of Arthur Kill are a small example of affected species which are affected by the world’s growing pollution.

Final Report:

The Raritan Bay and its neighboring waters were once the golden grounds for oyster catching in the Northeast. Prior to the 1930s, the East Coast oyster industry was a booming market with 67,000 workers who cultivated 73,000 tons of oysters a year.[1] In her article published in the Village Voice on the history of oyster farming, Karen Tedesco emphasizes the importance of Raritan Bay oyster farms. She includes the following quote from Mark Kurlansky’s book, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, to describe the success of oyster farms in this area: “… nineteenth-century New Yorkers ‘consumed as many as a million oysters a day,’ and [oysters from the Raritan Bay region] were shipped to far-flung aficionados in Chicago, San Francisco, Paris and London”[2]. Unfortunately, these waters were located near concentrated urban and industrial areas in the New York and New Jersey area; and being near these industrial areas left them vulnerable to contamination from sewers, public dump sites, and general industry pollution. With the addition of the numerous cargo ships passing through the Raritan Bay to reach the ports of Newark and Manhattan, the rich oyster populations were forced to face a great deal of adversity.

The contamination of these waters over the years led to a decline in oyster populations and created safety issues for oyster consumers. In his paper, History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey, Clyde Mackenzie describes the downfall of the oyster industry in this area due to the increase in water pollution and aims to emphasize the far-reaching influence of the industry. Mackenzie claims, “After 1915, the oyster industry declined steadily as newspapers reported human illness from typhoid fever, especially in Chicago, traced to Raritan Bay oysters”[3]. As Karen Tedesco had stated, Raritan Bay oysters were consumed worldwide. So, the effects of the Raritan Bay area oyster crisis were far-reaching beyond the New York/New Jersey area and affected thousands of people in other areas as well.

In addition to the far-reaching effects Mackenzie presents, when we consider the size of this industry, it is not difficult to imagine the impact of its decline had on the local communities. While scientific data has been collected on the impact of pollution on the local oyster population, no research has been done to study the effects of this pollution on local residents. By studying the source of water pollution in the Raritan Bay area water systems, steps taken to combat the pollution, and its impact on the livelihood of the region and its people, a more complete picture of this tragedy can be assembled. Understanding the entire picture will highlight the injustices experienced by local residents and provide valuable insight that can aid in the rehabilitation efforts of the region’s water systems.

Polluting the Raritan Bay

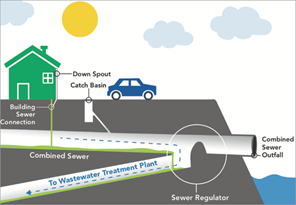

One of the biggest polluters of these waters is the combined sewage running from nearby cities. Prior to the construction of combined sewer systems, single-pipe systems were used by cities to transport sewage. However, this single-pipe system was prone to over-filling and flooding the streets during intense periods of rainfall. The combined sewage systems were constructed to overcome this problem by dumping untreated sewage into the ocean when the sewage system became overwhelmed. Without filtration, the sewage carried pathogens and pollutants straight into the heart of the aquatic ecosystems.

[4]

The sewage from nearby cities consist mostly of wet matter (approx. 60-70%), as well as some solid matter—which include both water soluble and insoluble waste. In a 1912 report written by the Metropolitan Sewerage Commission of New York, the writers estimate “… New York at 5,000,000 people, there is a discharged every day about 625 tons of fecal matter.”[5]

With no clean up procedures in place, and the ocean was left to clean itself with the help of bottom feeders and filter feeders alike. Oysters are one of these filter feeders that can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. However, oysters at the Raritan Bay could not handle the overwhelming amount of waste brought by the sewage from urban cities like New York and New Jersey. Oysters became infected and inedible due to the bacteria from the untreated sewage they filtered. As oysters became infected, their filtering became less efficient, and more and more oysters drowned in solid waste. As a result of decreased filtering and the unending amounts of incoming waste, oyster farms in the Raritan Bay area became extinct in 1925.

In his paper, Clyde Mackenzie describes the effect of pollution on the industry: “By 1925, the negative publicity had forced planters to abandon the oyster industry permanently.”[6] At this point, only a few oyster farmers were still working in the Raritan area. They were small in number and did not produce as many oysters as their predecessors. Many of the farmers cultivated oysters for research instead of selling them. These farmers attempted to measure the damage in order to understand whether the oyster population could be saved in these areas.

In 2010, Bob Martin, a commissioner for the New Jersey Department of Environmental, put out a statement to “…[ban] research-related gardening of commercial shellfish species in coastal and inner harbor waters classified as contaminated”.[7] This ban was put in place, both to protect researchers who came in contact with the shellfish from health risks, and to shield the $790 million-a-year shellfish industry from further public scrutiny.[8] The commissioner knew that oyster industry could not be revived if the public equated the industry with disease and uncleanliness, so all oyster operations in contaminated waters were brought to a halt. Cultivation of oysters continued in non-contaminated waters. Oysters from these areas were sent out to markets, and unsold oysters were used as filters in contaminated areas. The department supported oyster farming in select areas in hopes of an upward spiral for the oyster industry.

In its former glory, the oyster industry was the largest aquatic industry in the area from 1825 to 1915, creating jobs at oyster farms, boat yards, basket factories, lime kilns, freight boats, and railroads.[9] A total of 595 oystermen worked in the Raritan Bay and neighboring water systems during this time.[10] The economy boomed as the oyster trade brought in large sums of revenue for the surrounding regions. Unfortunately, these oystermen lost their jobs in 1927, when the last commercial oyster bed in the Raritan Bay area closed[11]. While many of these oystermen turned to other aquatic based jobs like fishing and clamming, these jobs were not as lucrative as oyster farming. At its peak, 500 active oyster vessels were at work in the Raritan Bay area, however this number fell to just 30 boats following the decline in oyster beds.[12]

The Decline of Oyster Farming

The oyster industry was a source of employment for the majority of residents in the Raritan Bay area, and when it collapsed, the lack of jobs drove many local families to poverty. The lack of jobs and high rate of unemployment lead to “… a drastic decline in the standard of living for many families with established roots in the region.”[13] A New York Times article from 1964 notes that oyster farmers were forced to ask for assistance from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in order to take care of their families.[14] However, even with assistance, some local residents continued to struggle and were forced to relocate to make a living elsewhere.[15]

As locals started earning less and less money, the amount of money in circulation also declined, which started choking local businesses. Accounts from locals detail drastic changes which reshaped the region following the oysters’ deaths. Locals such as Sheri Gatier claim “At one time there were car dealers and movie theaters, and department stores, … tons of speakeasies… Unfortunately, when (the oysters) died… it died.”[16] While another local, Rachel Dolhanczyk claims “…there were more millionaires here than anywhere else in New Jersey…”[17] In this way, the death of oysters not only left oystermen unemployed, but also put small businesses out of work. Over time, an increasing number of stores and shops started closing their doors, and soon enough the once lively Raritan Bay area became abandoned. As opportunities for jobs dried up and families moved away, the local communities shrunk and became more individualistic.

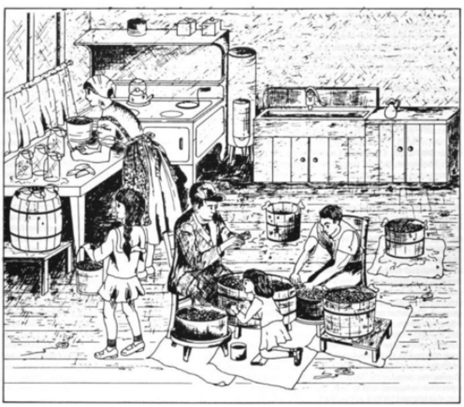

To expand on the impact of the declining oyster industry on local communities, it is important to understand the culture behind oyster farming. Cultivation of oysters is a job which requires collaborative group efforts, which is depicted by the image below. This image was created based on interviews with fisherman from 1930s to reflect the average household of oyster farmers and shows a family of five working together to clean/prepare oysters. The father is shown cleaning oysters with his two children, while another child brings these oysters to the mother, who is packaging the cleaned oysters into jars. Just as in the picture, oyster farmers in the Raritan Bay area would often work together like a family to prepare oysters. This group work helped establish stronger ties and relationships within the oystermen communities. However, as pollution started killing oysters in the Raritan Bay, competition among oyster farmers increased, which diminished their sense of community. The death of local communities residing in the area, as well as the decline in regional left only a shell of what the Raritan Bay area once was.

[18]

Conserving Oysters and Local Communities

However, this crisis was perhaps a necessary wake-up call for many people. Following the rise in pollution and oyster extinction, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) instated the Clean Water Act which “…establishe[d] the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the water”.[19] This act is still in effect today and has allowed for improvements in the water. Although it took many years to see the effects of the Clean Water Act, it started a precedence across the US and inspired people to protect their local ecosystems.

In addition to passing laws, the government also joined forces with local people to revive the oyster populations in this region. One of the prime examples of this collaboration is the Billion Oyster Project. Established in 2014, the project aimed to bring back one billion oyster to the New York harbor by the year 2035.[20] This project brought together students, volunteers, community scientists and restaurants across the five boroughs to teach the public about the rich history of New York and its oysters.[21] These efforts of the Billion Oyster Project are not only reviving oyster populations, but also actively helping rebuild the sense of community that was diminished due to the death of oysters.

People like Murray Fisher and Pete Malinowski from the Billion Oyster Project have predicted that through rehabilitation efforts such as this one, oysters can come back to the shores of New York and New Jersey. The project hopes that these new oyster populations will grow into reefs and stabilize the motion of water. New Jersey and New York have long coastlines with many residential areas, and water motion stability is crucial to safety of their residents. This significance is more obvious when considering the aftermath of natural disasters like Superstorm Sandy. Meredith Comi, the restoration program director for New York/New Jersey Baykeeper, considers oysters a great asset for protecting residential areas during storms. She comments that if these efforts are successful, “When another Superstorm Sandy comes through, it won’t stop the surge, but it will certainly slow it down”[22].

Unfortunately, these events are not unique to the Raritan Bay; in the Hippo Pool Village, water has been contaminated by a nearby mine for years and communities are facing even worse consequences.[23] Aquatic pollution is a widespread problem of our day, and we must spread awareness about its effects on our ecosystems, as well as people across the world. The numerous effects of the Raritan Bay oyster disaster prove how the health of our water systems impact people directly and indirectly, especially local residents. In an increasingly connected world, it is not possible to isolate problems, when the burdens of local disasters are felt globally. It is only natural to embark on global efforts to control aquatic pollution if we want to make real changes.

[1] Dan Flynn, “Oyster-Borne Typhoid Fever Killed 150 in Winter of 1924-25”, Food Safety News

[2] Karen Tedesco, “A Billion Oysters Tell the History of New York”, The Village Voice, last modified June 1, 2015, https://www.villagevoice.com/2015/06/01/a-billion-oysters-tell-the-history-of-new-york/

[3] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[4] “Combined Sewer Overflows”, NYC Environmental Protection, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/combined-sewer-overflows.page

[5] Soper, George A., James H. Fuertes, H. de B. Parsons, Charles Sooysmith, and Linsly R. Williams. Rep. “Present Sanitary Condition of New York Harbor and the Degree of Cleanness Which Is Necessary and Sufficient for the Water”, University of Michigan, Accessed November 16, 2020. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021042760&view=1up&seq=2

[6] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[7] “Commissioner Aims to Protect Public Health and Shellfish Industry”, State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, last modified June 7, 2010, https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2010/10_0053.htm

[8] “Commissioner Aims to Protect Public Health and Shellfish Industry”, State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, last modified June 7, 2010, https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2010/10_0053.htm

[9] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[10] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[11] “History of New York Harbor”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/harbor-history

[12] Kimberly R. Sebold, Sara Amy Leach, “HISTORIC THEMES AND RESOURCES within the NEW JERSET COASTAL HERITIGE TRAIL ROUTE”, U.S. Department of the Interior, last modified 1991, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/nj2/chap3b.htm

[13] “OYSTER INDUSTRY REVITALIZATION TASK FORCE”, last modified January 1999, https://www.state.nj.us/seafood/Oyster_Industry_Revitalization_Task_Force.pdf

[14] Port Norris, “Jersey Oyster Town Fights for Life”, The New York Times, last modified November 24, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/24/archives/jersey-oyster-town-fights-for-life.html

[15] Port Norris, “Jersey Oyster Town Fights for Life”, The New York Times, last modified November 24, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/24/archives/jersey-oyster-town-fights-for-life.html

[16] Catalina Jaramillo, “New Jersey oyster farmers betting on a comeback, climate permitting”, State Impact Pennsylvania, last modified August 11, 2017, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2017/08/11/new-jersey-oyster-farmers-betting-on-a-comeback-climate-permitting/

[17] Catalina Jaramillo, “New Jersey oyster farmers betting on a comeback, climate permitting”, State Impact Pennsylvania, last modified August 11, 2017, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2017/08/11/new-jersey-oyster-farmers-betting-on-a-comeback-climate-permitting/

[18] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[19] “Summary of the Clean Water Act”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act

[20] “History of New York Harbor”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/harbor-history

[21] “Our Story”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/our-story

[22] Michael Sol Warren, “Baby Oysters Discovered in a N.J. Bay Are Cause for Celebration. Here’s Why”, NJ.com, last modified January 16 2019, https://www.nj.com/news/2017/12/raritan_bay_oyster_reef_has_started_reproducing_na.html

[23] John Vidal, “I drank the water and ate the fish. We all did. The acid has damaged me permanently”, The Guardian, last modified August 1, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/aug/01/zambia-vedanta-pollution-village-copper-mine

[1] Dan Flynn, “Oyster-Borne Typhoid Fever Killed 150 in Winter of 1924-25”, Food Safety News

[2] Karen Tedesco, “A Billion Oysters Tell the History of New York”, The Village Voice, last modified June 1, 2015, https://www.villagevoice.com/2015/06/01/a-billion-oysters-tell-the-history-of-new-york/

[3] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[4] “Combined Sewer Overflows”, NYC Environmental Protection, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/combined-sewer-overflows.page

[5] Soper, George A., James H. Fuertes, H. de B. Parsons, Charles Sooysmith, and Linsly R. Williams. Rep. “Present Sanitary Condition of New York Harbor and the Degree of Cleanness Which Is Necessary and Sufficient for the Water”, University of Michigan, Accessed November 16, 2020. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021042760&view=1up&seq=2

[6] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[7] “Commissioner Aims to Protect Public Health and Shellfish Industry”, State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, last modified June 7, 2010, https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2010/10_0053.htm

[8] “Commissioner Aims to Protect Public Health and Shellfish Industry”, State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, last modified June 7, 2010, https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2010/10_0053.htm

[9] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[10] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[11] “History of New York Harbor”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/harbor-history

[12] Kimberly R. Sebold, Sara Amy Leach, “HISTORIC THEMES AND RESOURCES within the NEW JERSET COASTAL HERITIGE TRAIL ROUTE”, U.S. Department of the Interior, last modified 1991, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/nj2/chap3b.htm

[13] “OYSTER INDUSTRY REVITALIZATION TASK FORCE”, last modified January 1999, https://www.state.nj.us/seafood/Oyster_Industry_Revitalization_Task_Force.pdf

[14] Port Norris, “Jersey Oyster Town Fights for Life”, The New York Times, last modified November 24, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/24/archives/jersey-oyster-town-fights-for-life.html

[15] Port Norris, “Jersey Oyster Town Fights for Life”, The New York Times, last modified November 24, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/24/archives/jersey-oyster-town-fights-for-life.html

[16] Catalina Jaramillo, “New Jersey oyster farmers betting on a comeback, climate permitting”, State Impact Pennsylvania, last modified August 11, 2017, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2017/08/11/new-jersey-oyster-farmers-betting-on-a-comeback-climate-permitting/

[17] Catalina Jaramillo, “New Jersey oyster farmers betting on a comeback, climate permitting”, State Impact Pennsylvania, last modified August 11, 2017, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2017/08/11/new-jersey-oyster-farmers-betting-on-a-comeback-climate-permitting/

[18] Clyde L. Mackenzie Jr., “History of Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey”, accessed November 26, 2020, https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/MFR/mfr524/mfr5241.pdf.

[19] “Summary of the Clean Water Act”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act

[20] “History of New York Harbor”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/harbor-history

[21] “Our Story”, Billion Oyster Project, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.billionoysterproject.org/our-story

[22] Michael Sol Warren, “Baby Oysters Discovered in a N.J. Bay Are Cause for Celebration. Here’s Why”, NJ.com, last modified January 16 2019, https://www.nj.com/news/2017/12/raritan_bay_oyster_reef_has_started_reproducing_na.html

[23] John Vidal, “I drank the water and ate the fish. We all did. The acid has damaged me permanently”, The Guardian, last modified August 1, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2015/aug/01/zambia-vedanta-pollution-village-copper-mine

Primary Sources:

Source 1:

Facts:

Present Sanitary Condition of New York Harbor and the Degree of Cleanness Which is Necessary and Sufficient for the Water

Online source digitized by Hathi Trust

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021042760&view=1up&seq=7

The main use of this source will be in seeing how the water has changed around the time of this publication. By looking at the water change in 1912 I can create connections between then and now.

Analysis:

Present Sanitary Condition of New York Harbor and the Degree of Cleanness Which is Necessary and Sufficient for the Water written by five individuals who work for the Metropolitan Sewerage Commision of New York expresses the current state of bodies of water around New York and New Jersey. Using empirical data with expert consultants they are able to determine the state of the water and the way it should be remedied. Throughout the paper the writers and experts believe that the water is not clean and should be. The water is very polluted and should be cleaned as people will use it for their own activities.

The waters of New York and New Jersey are fairly slow when it comes to water velocity. The average speed of the water is approximately 1.2 miles per hour. This is low considering that the average speed is 7 miles per hour. A slow water speed means that the sewage in the water is almost stagnant so it has a larger amount of time to infect the area around it. With this infection spreading the wildlife in the water would be unsafe to consume. “The danger of accidental and direct pollution would make the taking of shellfish for food unsafe”. Shellfish being “an extensive industry in Lower New York bay” is a great source of income for many people living in the area. Dangering these species would not only danger the people who consume them but also the jobs and livelihood of the people who capture and sell these fish. “All the experts considered it impracticable to keep the waters in the inner part of New York harbor pure enough for oyster culture”. All experts agreed that with the current conditions it would be impossible for oysters to be made a constant part of the New York scene. Some experts believed “that it might ultimately be necessary to sacrifice all oyster beds” due to the inability of the water to be clean. With practices that include more processing of sewage and eliminating direct pollution the natural oyster beds can come back.

Source 2:

Facts:

Commissioner Aims to Protect Public Health and Shellfish Industry

Department of Environmental Protection site

https://www.nj.gov/dep/newsrel/2010/10_0053.htm

Prove that the shellfish industry is massive and any damage done to the environment hurts the workers within it.

Analysis:

The Commissioner of the Department of Environment Protection wanted to stop the cultivation of tainted oysters and other shellfish. This was in order to protect people from any contamination in the water and that can travel to people through the shellfish. With the information that this release will give you can see how important the shellfish industry is to the people living near the water.

With an industry that is worth $790 million a year in just New Jersey one can see that it should be well protected and monitored. With the emergence of pollutants the shellfish become sick and can lead to hurting people who consume them. “If someone gets sick from eating shellfish from contaminated waters, people may stop buying or eating New Jersey products or shellfish from approved waters”. This was in order to not have “contaminated oysters or clams getting into the public food supply” because once they are in the consumers will get sick. Once they get sick the million dollar industry will crumble. The danger doesn’t only come from legal fishing in contaminated areas but also from illegal harvesting. With rules and regulations that need to be followed anyone who isn’t certified can harvest anywhere. Without knowing the regulations the poachers could send contaminated food into the stores and get people sick, causing people to no longer trust the local produce and crashing the industry.

Source 3:

Facts:

Long-Term Improvements in Water Quality Due to Sewage Abatement in the Lower Hudson River

Part of the Jstor library

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1352305

This source would be useful in showing the ways that the water has improved

Analysis:

Out of all the sources that are upset with the conditions that the waters are in this one has a different opinion. By looking at the past and comparing it to current statistics these authors are able to show that there are many steps that have been taken in order to build a better water quality. Although pollution is still an issue there are steps being taken in order to fix and remedy the toxins.

With the “increased capture and treatment of municipal sewage” the waters of the Hudson River have been able to clear up. With the biggest pollution problem being sewage from the people of the city an increase in treatment means less direct dumping into the water ways. A boost in cleanliness means a boost in the way of life not only for the people around but also for the flora and fauna of the region. “Efforts have abated 0.19 m3s-1of untreated sewage city-wide” meaning that the increase of treatment has greatly reduced the amount of sewage that is directly flowing into the river. By looking at figure 5 in the article gives the reader an understanding of the drastic change that 23 years of treatment can do. Being the worst possible scenario to some of the cleanest water in less than three decades shows that the people of New York are devoted to the cause of fixing the water. By the end of 1995 the water was good enough to bring back shellfishing and to bring back a whole industry into the economic sphere of New York.

Secondary Sources:

Image Analysis:

The image depicts a family of five that is working together on making a meal. The father, who is also a fisherman, cleans the oysters with his son and daughter while another daughter brings the cleaned shellfish to the mother who packages them into jars for later use. This image makes the viewer see that oysters are an important part of a family dynamic as it brings them closer together. This is very important in areas like Raritan Bay and the Arthur Kill River as those areas have neighboring towns where the family structure may be not as strong.

This image was made in the 1930’s when oysters were in abundance so most fishermen were able to not only provide monetary stability but also bring food for the family. The image was produced for a paper about the history of fishing in the area around Raritan Bay. It used data collected from fisherman interviews in order to show the average fisherman household. Knowing what the average household did with its prosperity leads the viewer to see how important these shellfish are to the community and the people that live there.

The image shows five family members all working together to prepare their meal. They have cleared their kitchen for this one task to do all together. This shows that the existence of the oysters lead to closer family ties. Although it wasn’t the sole event that kept families together it definitely did not hurt them. The time family shares preparing dinner and overall spending time together creates stronger bonding. These bonds are great for the community as a strong family can help themselves as well as others. Strong communities stem from creating strong family ties within the community.

The barrels full of clams leads the viewer of this image to assume that the clams were very abundant. Being a fisherman allows for the fisher to bring food to his family when the harvest is plentiful. This image shows that the harvests are very fruitful and so he is able to not only provide income for the family but also feed them. With an abundance of clams families can be certain that food will not be a priority and thus choose to focus their efforts on other things like helping better the environment and the area they live in.

Although the barrels are plentiful this does not mean that the family isn’t struggling in other ways. Fishermen weren’t known to be the richest of people. With the loss of water crops the people to first lose their work would be the fisherman. This would put strain on the families who rely on the water for their existence. When the population dies off the people will have to find new ways to survive which can cause massive tension between the members of the community.

Through the image a message of family cohesiveness is conveyed. The abundance of shellfish lets the viewer know that these products were a livelihood for a group of people. With this abundance comes food that needs to be prepared by the family. This preparation allows for the whole family to get involved creating stronger family ties. When family ties get strained the community can fall as a whole. Creating unrest in a way of life. Areas like Raritan Bay and the Arthur Kill river saw this unrest. When many fishermen lost their ability to provide an income the family struggled and so had to find new forms of cash flow. With the growing job loss due to pollution this problem becomes more and more prevalent. Due to the loss of harvestable area overpopulation has also become an issue. With overpopulation the amount of fishermen also decreases. A chain of events can start a massive loss of jobs and a long standing way of life that brings great local oysters to the people of Raritan Bay.