Operation Rolling Blunder:

Agent Orange’s Newark Legacy and the Fight to Clean Up the Ironbound

by Ryan Giust

Site Description:

The Diamond Alkali plant, later known as Diamond Shamrock after its merger with Shamrock Oil and Gas, was located at 80-120 Lister Ave in the Ironbound section of Newark, NJ. It is widely known as the producer of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was an extremely toxic herbicide used for clearing the jungles of vegetation so the Viet Cong could not hide and ambush US troops. It is linked to cancer and birth defects among the Vietnamese population as well as troops that served there. This paper will focus on how a by-product of the manufacturing process of Agent Orange, dioxin, affected the Newark area, as well as the activism by Ironbound residents to get it cleaned up. Dioxin is an extremely toxic chemical that the Diamond Alkali company dumped into the Passaic River and its carelessness in handling and storage also resulted in the ground water being polluted, and the chemical spread throughout the Ironbound unknown for years. The Diamond Alkali plant was classified as a Superfund site in 1984, and the environmental side effects are still being dealt with today.

My research question is: What role did the activists play in getting the parties responsible to clean up and contain the dioxin? Why were they successful and what did they do? I also want to look into whether the Newark area is considered safe now and any current concerns regarding the Diamond Alkali site. The cleanup is still ongoing, particularly with the Passaic River and it would be relevant to include how that is being carried out and what future plans there are for the cleanup.

Final Report:

Introduction

The Diamond Alkali plant, later known as Diamond Shamrock after its merger with Shamrock Oil and Gas, was located at 80-120 Lister Avenue in the immigrant neighborhood, known as the Ironbound, in Newark, New Jersey. The plant is widely known as a producer of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was an extremely toxic herbicide used for clearing the jungles of vegetation so the Viet Cong could not hide and ambush American troops. It is linked to cancer and birth defects among the Vietnamese population as well as troops that served there. Dioxin, a by-product of the manufacturing process of Agent Orange, is an extremely toxic chemical that the Diamond Alkali company dumped into the Passaic River, which was the northern boundary of the property. The company’s carelessness in handling and disposal resulted in the water and soil being polluted, letting the chemical spread throughout the Ironbound, unknown to the residents for years. The Diamond Alkali plant was classified as a Superfund site in 1984, and the environmental side effects are still being dealt with today.

Before starting this project, I had not found much information on Diamond Alkali except for some basic facts such as that it was the cause of the dioxin contamination in the Ironbound and that dioxin caused numerous serious medical problems for anyone exposed to even minute amounts of the substance. I was curious as to what was done about the situation and if the Ironbound is safe today, or if there are still traces of dioxin to be found despite the cleanup effort. I also wanted to know why activism was needed in the first place and what the government response was to it. Besides periodicals, there are currently very few published works written on the dioxin fiasco in the Ironbound, making it difficult to find a substantial amount of information on the subject. Most of the sources I have used in the writing of this paper are documents from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Ironbound periodical, Ironbound Voices, sources from the Dioxin clippings file at the Newark Van Buren Branch Library, and the New Jersey state newspaper, The Star Ledger.

My project aims to dive deeper into the issue and examine the government’s failure in response to the dioxin as well as the activism by Ironbound residents demanding justice. First, I will explain the site history, government test results, as well as the demographics of the area, as these sections will provide necessary information to understand why the activism was needed. Health effects of dioxin and the government’s response to its discovery in the Ironbound will be discussed next. Finally, the activism itself will be discussed, paying specific attention to what was done and who was involved. Without pressure on the government by the Ironbound activists, the cleanup of the Diamond Alkali site and dioxin in the Ironbound would have taken much longer than it already had and it would not have been as effective.

History and Test Results

The site at 80 Lister Avenue had a long history of industrial chemical production. Records show that the development began there as early as the 1870s and drawings from 1914 indicate the site belonged to the Lister Agricultural Chemical Company. After the closure of the company, the land was purchased by Kolker Chemical Works, Inc., and production of various agricultural chemicals began on the site. These primarily included dichlorodiphenyl trichloroethane (DDT) and phenoxy herbicides, both of which have since been banned from use. In 1951, Kolker Chemical Works was absorbed by the Diamond Alkali Company. Within the following years, the production of most chemicals ceased or was transferred to other facilities with the exception of phenoxy herbicides.[1]

An explosion in 1960 damaged the production processes of the plant and thus solidified the decision to only focus on phenoxy in the future, including 2,4,5-T, a major component that would be used to make Agent Orange. The plant was rebuilt and upgraded during the 1960s, which doubled the production capacity for the phenoxy herbicides, bringing it up to 15 million pounds per year. The final expansion of the plant took place in 1967, which involved converting an existing building to manufacture 2,4,5-T for the production of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. A carbon filtration process designed to remove dioxin was also installed during this conversion.[2]

The plant was shut down in 1969 and remained dormant until 1971, when it was purchased by Chemicaland. Operation started and stopped over the next few years and Occidental Chemical Company managed the plant briefly while considering purchasing it from Chemicaland. The sale never happened and control was returned to Chemicaland. The company was not able to continue operation due to financial reasons so they shut the plant down for the last time in 1977. The plant changed hands twice more between 1980 and 1981 and was acquired by Marisol, Inc. They began clearing the property, and at some point they put the waste left from the last operation into drums, which remained on site. At some point, Marisol also began leasing the property to SCA Corp, and in preparation for their use of an office building on site, samples were taken around the property in April of 1983 by the Environmental Protection Agency.[3]

The results showed extremely high levels of dioxin, leading to the NJ Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) taking control of the property. There were 63 surface soil samples taken at varying locations and depths and all contained dioxin. The concentrations of dioxin ranged from 0.39 to 19,500 parts per billion (ppb).[4] Put in perspective, the Federal Government declared that dioxin levels above 1 ppb are hazardous to human health.[5] There were 17 ground water samples taken from the site, and of those, 15 had dioxin concentrations of up to 10.4 ppb. The water and sediment from the Passaic River was also analyzed. The two samples of river water showed small dioxin concentrations of 0.004 and 0.007 ppb, while 26 of the 36 sediment samples had dioxin concentrations up to 130 ppb. Other tests done in the buildings and chemical tanks yielded dioxin concentrations of up to 60,800 ppb.[6] Being that the highest concentrations of dioxin were inside, they did not pose as much of a health risk as the dioxin outdoors in the soil and water. The dioxin in the soil left the Diamond Alkali site by means of wind. The wind would blow dioxin off the property, allowing it to become widely spread. The dioxin in the streets would become attached to truck tires that would transport it elsewhere in the community. Dioxin attaching to animal fur and peoples’ shoes were also ways the toxin spread.[7] The ease with which dioxin moved around the Ironbound left the community and surrounding area particularly at risk.

Demographics of the Area

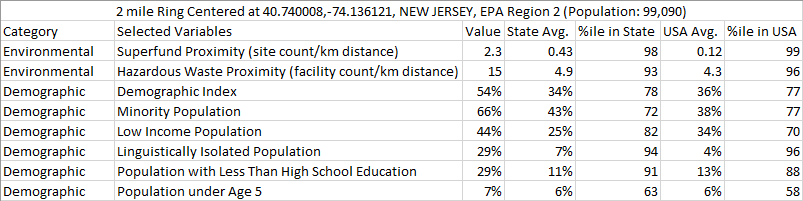

According to the EPA data, over 99,000 people living within two miles of the Diamond Alkali site are in the 99th percentile nationwide regarding proximity to a Superfund site, meaning 99 percent or more of the total population of the US do not live near a superfund site. Statewide, the data shows that only 2 percent of people live as close to a site. The data suggests that the people living close by the Diamond Alkali site were at a higher risk of exposure to toxic chemicals than nearly the entire population of the US. While most people live away from toxic sites, the Ironbound is particularly disadvantaged due to the dioxin contaminated soil and the groundwater underneath it. The fact that the Ironbound is the lowest area in Newark means the dioxin is closer to the surface than in the surrounding areas. People living away from superfund sites are less likely to encounter pollution the further they are from them. The exposure of thousands of people to such a toxic substance is an unfortunate injustice on its own, however the demographics of the area show an even greater injustice.[8]

The Ironbound is a very diverse neighborhood and has always been home to a largely immigrant population. Because the Ironbound is the primary concern for this paper and it differs from the area across the Passaic River in several ways, I have used a second set of data that specifically focuses on the Ironbound neighborhood demographically. Minorities in the Ironbound comprise 66 percent of the population, a rate that is higher than the minority population of 72 percent of New Jersey. Furthermore, 49 percent of the Ironbound population is low income, as compared to a state average of 25 percent and a national average of 34 percent. Forty percent of the Ironbound is linguistically isolated, which is remarkable since the state and national averages are 7 percent and 4 percent respectively. The Ironbound population with less than high school education is 37 percent, while the state average is 11 percent and the national average is 13 percent.[9]

The data makes it extremely clear that the Ironbound is disadvantaged in numerous ways and this is also a reason why I chose to use data from the Ironbound only for this section. It is reasonable to assume that the demographics have not changed much since the 1980s, when dioxin was discovered at Diamond Alkali. While the leakage of the dioxin might not have been intentional, it put an already extremely disadvantaged population at an even greater disadvantage that is harmful to their health. The population had been suffering cancer and birth defects as a result of dioxin exposure, and it still continues to experience negative health effects to this day. The low education level of a third of the population certainly was not helpful when going up against the government, and it likely made the government think the residents would be push-overs. The data overall shows a significantly disadvantaged population in the immediate area of the Diamond Alkali Superfund Site.

Health Effects of Dioxin and Government Lies

Dioxin’s health effects are necessary to fully appreciate why the Ironbound residents were fighting. The first cases of the effects of Dioxin in the Ironbound come from the men who made Agent Orange at the Diamond Alkali plant. The production of the herbicide released the by-product dioxin, to which the workers were routinely exposed. They developed a condition known as chloracne, and though this sounds like merely teenage acne, it is in fact much worse and produces disfiguring boils and cysts. These were removed by company doctors but the situation was kept quiet by Diamond Alkali, costing the lives of 30 of the original 75 workers, as of July, 1984.[10] A plethora of other health effects are possible with dioxin exposure including liver damage, cancer, heart and lung problems, birth defects, damage to immune system, and kidney diseases, among many other serious illnesses.[11] Before dioxin was discovered in a public pool in the Ironbound, the children that swam there developed severe skin rashes. A local Parent Teacher Association President commented that one girl’s face looked like “raw meat”.[12]

Nancy Zak, a local activist with the Ironbound Community Corporation, which has fought for environmental justice in the neighborhood, recalled a similarly distressing experience in an oral interview. In the following quote from the interview, she described how a former student of hers was affected by dioxin: “When I saw that young girl who I had taught in high school, she had played on those hills that were covered with the dioxin dirt, she had told me she was losing her eyesight and her kidney functions, and she had two babies and both of them had birth defects,” Zak explained. “And I thought she must have been affected by that dioxin because she was running up and down those little hills, which children would have done.” Zak continued: “When you saw that it, was like being punched in the gut. You really saw that this is what it’s all about”.[13] Zak’s story is not unique, as many Ironbound residents suffered similar fates from dioxin exposure. For their friends and relatives, their failing health became a driving force behind the activism, much like it had been for Nancy.

To listen to the full interview with Nancy Zak, click on the link below:

Despite the suffering dioxin had caused, the government was aware that the Diamond Alkali plant was a cause for concern earlier than 1983. It was in 1983 that there was actual testing done on the site, yet the government waited a month to report the findings to the public. It should be noted, however, that when the state government was pressed for answers, they finally admitted to receiving a Federal report that there was likely dioxin at Diamond Alkali in 1980. Worse yet, the EPA reported on dioxin contamination at the site in 1974, nearly a decade before the official tests were done. This was brought to light thanks to Barry Commoner, a prominent environmental scientist working with the activists. Studies existed beforehand as far back as 1962 that showed that workers of Diamond Alkali were getting sick.[14] This negligence of the government would prove to be a common theme in the months and years following the 1983 discovery of dioxin, along with shirking of duty and outright lies.

The government and its agencies did not act in the best interest of the Ironbound residents, who had to put up with countless lies and blame shifting. New Jersey Governor Kean announced the discovery of dioxin on June 2, 1983, a month later than it should have been announced, and he also claimed that there was no way to test for dioxin prior to then. In fact, that was a blatant lie. Dioxin testing was available ten years earlier. Published results from testing done in 1973, though not at the site, are proof that scientists were able to detect even smaller quantities of dioxin than the smallest amount found at Diamond Alkali in 1983. The testing however, was expensive, and despite there being no solid evidence proving that this was the reason testing was not done sooner, it is reasonable to say that the government simply did not want to spend the money to protect the residents of the Ironbound.[15]

Another instance of dishonesty on the part of the government is on the movement of dioxin. Kean said the dioxin was contained within the Diamond Alkali property, despite tests showing that it had migrated outside, contaminating the streets, the farmers market, and other locations. The excuses from the government included blaming the dioxin found in these places on herbicides, despite the fact that herbicides containing dioxin had been banned and were not used since 1970.[16] In yet another case of the government not wanting to incriminate itself, the Department of Environmental Protection was ordered by Judge Stanton of the Essex County Superior Court to provide the Ironbound community with all information pertaining to the dioxin.[17] Months later, they still had not released any information, despite promising Judge Stanton that it would be released.[18] Clearly the government did not want to let the truth out and most likely had crooked reasons for withholding it.

Activism in the Ironbound

The government’s failure described above is largely the reason why the Ironbound activism was needed. The activism consisted of neighborhood meetings with government officials and protests, which generated publicity in favor of the movement. The Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste was the spearhead of the movement. It held the first Ironbound-wide meeting for residents immediately after the announcement of the presence of dioxin. The community demanded transparency and more sampling, as well as experts to review information provided by the state. Weekly meetings were held thereafter, focusing on the lack of health testing and scant dioxin sampling. Word was spread rapidly throughout the neighborhood. Posters were placed in windows and personal visits were made to peoples’ homes. Phone calls and mailings were also used to organize.[19]

The Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste and the residents were proactive in other ways by taking direct political action. They met with elected city officials regularly with the intention of gaining their favor and seeking all the information they can possibly get on the situation as it stood. Councilman Martinez of Newark introduced a resolution supporting residents’ demands at a City Council meeting. Residents threw their support behind it and the resolution passed. Concerns attached to the resolution included questions as to whether there will be health testing and further dioxin testing. Some residents met with Essex County Freeholders Parlavecchio and Cifelli, who also introduced resolutions at the Board of Freeholders. The residents met with assemblymen and reached out to Congressman Florio and the New Jersey Senators Lautenberg, Bradley, and Rodino. As of September 1983 when this article was written, the residents were awaiting responses from them, but it is assumed they responded favorably based on the favor they have gained of other elected officials.[20]

Public protests and marches were just as much a factor in garnering support for the residents’ cause. Publicity works wonders for all good causes, especially when it is an underdog against a large, dishonest organization such as the government. The first march was small, at just over 100 people marching down Ferry Street, a main road in the Ironbound. Their demands were simply transparency and a request for further sampling.[21] As momentum built, marches would be held in various places, such as in front of an official’s house, specifically to maximize press coverage.[22] More residents would join in and the different types of people there would have a large effect on their popular support. Children and babies were particularly at risk from dioxin, and their mere presence was enough to sway people on a vast array of issues. It made sense to showcase the children for their own benefit. Vietnam veterans were another group that swung public favor strongly in the direction of Ironbound residents and the veterans themselves, who had their own grievances to air. Veterans organizations formed the Veterans Coalition to seek, much like those in the Ironbound, medical treatment for themselves and their children, as well as compensation for damage to their health.[23]

While looking through pictures of the protests, I came across a particular one I found very interesting and I have analyzed it here (see photo below). The image depicts protesters in action, focusing on a mother and her two children holding signs, with other protesters in the background. All of their signs bear confrontational messages directed at Diamond Alkali. Protesters like them played a large role in getting the Ironbound cleaned up through their activism. This image shows that the dioxin affects the entire community, particularly the children, but also their fathers who may have been exposed to Agent Orange while at war, or as workers at the plant.

Children were victims of the dioxin exposure just as the adults were, and they were equally important in the protests to clean up the Ironbound, as this image shows. Among the first things to catch my eye when viewing the image were the woman with a doll that was holding a sign and the two children in the foreground, each holding a large picket sign themselves. While the doll was not a real baby, it was representative of one. Its purpose was to give a voice to babies through the writing on its sign, as they were affected by dioxin more than anyone. Being that infants are still developing, exposure to dioxin at such an early stage would have likely caused severe medical problems that would have manifested themselves in childhood. The babies might have even been born with birth defects from the dioxin affecting their bodies prenatally, as in Zak’s story mentioned earlier. The effects of dioxin on the young and unborn cannot be understated.

The two children standing in the foreground are likely siblings and belong to the woman holding the doll. Each holds a picket sign with a confrontational message directed at Diamond Shamrock (Alkali). On the left is a boy about eight to ten years old and his sign says, “Diamond Shamrock WHY did You Hurt my DADDY and ME?”. His sister stands beside him and looks to be about the same age. Her sign says, “Diamond Shamrock Why are you Killing our Dads?”. It was likely Diamond Alkali did not care much about the children any more than the adults or they would have been more careful with the disposal of waste, however the children were most likely present at the protests and in this picture for publicity purposes. When children are affected, it prompts more calls for action, so children were probably instrumental in getting the Ironbound cleaned up. Their signs directly implicate Diamond Alkali as the cause of the dioxin contamination and make it clear that they are solely to blame. Pressure from the children at the protests gained power if the picture was made public since it tugs at peoples’ emotions and makes them more likely to take a stand on the side of the protesters.

Like the children, another group suffering from dioxin exposure were the men of the community, as mentioned on the picket signs in the image. When taking this picture at face value, it is clear that whole families were affected by the dioxin, and while there was only one man in the picture, the children’s signs ask Diamond Alkali why they were hurting their fathers as well as themselves. Looking deeper, it is interesting that their signs specifically call to mention their father, who may have been a plant worker who was exposed while working at Diamond Alkali. Even more likely is that he may have been a Vietnam veteran exposed to Agent Orange while overseas. Their father is not in the frame, and this leaves room to wonder where he is. Perhaps he is hospitalized as a result of exposure to dioxin, or perhaps he was simply unable to attend the protest. However, he is mentioned on their sign, and again children can be powerful weapons when it comes to activism.

In the interview with Zak, she recalled the veterans eventually joining forces with the Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste since their causes were similar and they attended multiple demonstrations together.[24] Veterans as a group occupy a special place in American society. While America was split on involvement in Vietnam and it resulted in the withdrawal of troops from the war, soldiers have always been the defenders of freedom in this country. While many did not agree with the war effort and the war was still on everyone’s mind, war veterans were respected. The fact that they were hurt by Agent Orange and dioxin by the United States government is first of all ironic, and second, it is symbolic. The Vietnam veterans represent American freedom under attack by the government and big business.

Conclusion

The dioxin fight has long since quieted down but such grassroots activism by Ironbound residents payed off. In September of 1987, the EPA came to a decision on how to stop dioxin from leaving the Diamond Alkali site. As listed on the EPA website and documents following the decision, the “Interim Containment Remedy” involved entombing the dioxin at the site, rather than transporting it to somewhere else for disposal. Subsurface slurry walls and a flood wall were constructed, as well a system for collecting and treating groundwater. To top it all off, quite literally, a cap was placed over the site to keep everything inside. This was done and paid for by Occidental Chemical Corporation, the latest owner of the site and party deemed responsible to cover costs relating to the cleanup. As is always the case with the government, this all took a long time, as construction was finally completed in 2001. Occidental still monitors the site and it is reviewed every few years to determine if there are better options available for dealing with the dioxin as technology progresses. That is why this is called the Interim Containment Remedy.[25]

Since 1994, Occidental has been investigating the waterways affected by Diamond Alkali, starting with the Passaic River. Their study showed that the contaminated sediment moved up and down the Lower Passaic River, most likely due to the tide. This led the way to a more in depth study of the Lower Passaic River Study Area in 2002, which looked at the entire 17-mile stretch. The Passaic was dredged in two areas in 2012 to remove contaminated sediment in an operation known as the “Tierra Removal”. Currently, there are plans in motion to dredge the lower 8.3 miles of the river in order for it to be capped without worsening flooding. Once approved, the plan will be implemented in the coming years.[26]

Though the dioxin at the Diamond Alkali Superfund Site is currently contained and under control, the Passaic River remains as the lasting legacy of dioxin in Newark, but it too is in the process of being cleaned up. Progress has been made and the river is clean enough now that kayaking trips from Riverfront Park in Newark are possible. Ironbound activist Nancy Zak recommends though, that the kayakers take a shower after being out on the water.[27]

It is truly amazing what the Ironbound residents accomplished. Their activism was crucial in getting the neighborhood cleaned up, and their efforts have proven to be very fruitful in that the clean-up is still ongoing, long after their attention has shifted elsewhere to tackle injustice after injustice. Despite the speedbumps along the way, dealing with government lies and halfhearted attempts at the cleanup, they have proven to be absolutely necessary for the safety of the Ironbound and serve as a beacon of hope for all communities in similar environmentally unjust situations.

[1] Christopher Dagget, “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987), 10.

[2] Christopher Dagget, “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987), 10-12.

[3] Christopher Dagget, “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987), 12-13.

[4] Christopher Dagget, “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987), 13-16.

[5] Tom Johnson, “Newark Residents and Ex-Workers Sue on Dioxin”, Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), June 14, 1983.

[6] Christopher Dagget, “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection” (US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987), 15-18.

[7] “Dioxin in Ironbound”, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[8] EJSCREEN EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool

[9] EJSCREEN EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool

[10] Matt Krautheim, “Diamond Shamrock Workers and Agent Orange”, Vol. 7 Issue 4, July, 1984. As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[11] “Health Effects”, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[12] “People Organize Protection From Deadly Dioxin”, Ironbound Voices (Newark, NJ), August, 1983.

[13] Nancy Zak (Activist at the Ironbound Community Corporation) in discussion with Ryan Giust, April 2019.

[14] “Ironbound vs. Dioxin”, Ironbound Voices (Newark, NJ), July, 1983.

[15] “Ironbound vs. Dioxin”, Ironbound Voices (Newark, NJ), July, 1983.

[16] “Dioxin in Ironbound”, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[17] “Next Round in the Fight Against Dioxin”, September, 1983. As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[18] “Breaking the Wall of Secrecy”, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[19] No author or title on this page, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[20] “Next Round in the Fight Against Dioxin”, September, 1983. As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[21] No author or title on this page, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[22] Nancy Zak (Activist at the Ironbound Community Corporation) in discussion with Ryan Giust, April 2019.

[23] “Veterans Say Make the Company Pay”, as found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

[24] Nancy Zak (Activist at the Ironbound Community Corporation) in discussion with Ryan Giust, April 2019.

[25] “DIAMOND ALKALI CO. Site Profile,” EPA, October 20, 2017, Accessed May 13, 2019, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0200613.

[26] “DIAMOND ALKALI CO. Site Profile,” EPA, October 20, 2017, Accessed May 13, 2019, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0200613.

[27] Nancy Zak (Activist at the Ironbound Community Corporation) in discussion with Ryan Giust, April 2019.

Bibliography

“Breaking the Wall of Secrecy.” As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

Dagget, Christopher. “Record of Decision Remedial Alternative Selection.” US Environmental Protection Agency, 1987.

“DIAMOND ALKALI CO. Site Profile.” EPA. October 20, 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0200613.

“Dioxin in Ironbound.” As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

EJSCREEN EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2018). https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

“Health Effects.” As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

“Ironbound vs. Dioxin.” Ironbound Voices (Newark, NJ), July, 1983.

Johnson, Tom. “Newark Residents and Ex-workers Sue on Dioxin.” Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), June 14, 1983.

Krautheim, Matt. “Diamond Shamrock Workers and Agent Orange.” 7, No.4 (1984). As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

Nancy Zak, interview by Ryan Giust, April 5, 2019.

“Next Round in the Fight Against Dioxin.” September, 1983. As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

“People Organize Protection From Deadly Dioxin.” Ironbound Voices (Newark, NJ), August, 1983. As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

“Veterans Say Make the Company Pay.” As found in the Dioxin clippings file in the Ironbound Community Corporation Archives, Van Buren Branch Library, Newark, New Jersey.

Primary Sources:

Record of Decision: Remedial Alternative Selection

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/02/83052.pdf

This document contains a description of the cleanup plan and a timeline leading to the final Record of Decision for the Interim Remedy, which was finally completed in 2001. There is also a description of the site location, geological information for the site, information on surface and ground water based on the initial samples taken, and a detailed history of the site going back to the 1870s. In my research paper, I will be looking into the history of the cleanup effort and how effective it has been at containing and decontaminating the area around the former Diamond Alkali plant. This document will help me in writing the background of the site as well as the initial cleanup effort, which will allow me to compare it to the site and area today. The interim remedy was intended to contain and decontaminate the site itself, and it will be useful to know what was done when I make that comparison.

Administrative Order No. E0-40-1

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/02/58070.pdf

This document contains many orders from the NJ Department of Environmental Protection, pertaining to Governor Kean’s Administrative Order No. 40. That order declared a state of emergency over the dioxin contamination from the former site of the Diamond Alkali plant and it gave Commissioner Hughey of the NJ DEP authorization to take whatever steps necessary to protect the health of the citizens of NJ. There are numerous individual orders within this document relating to steps taken in the Newark area to protect the public health and it will be useful when doing research on how effective the cleanup was. For example, there is a ban on fishing in the river and Newark bay. Determining when or if that ban was lifted will tell me when the area was deemed safe or if it is still unsafe.

3A. Administrative settlement agreement and order on consent for remedial design CERCLA docket No. 02-2016-2021 for Occidental Chemical Corporation for OU2 for the Diamond Alkali Company site

3B. Appendix B (Statement of Work)

The main document listed above is the settlement between the EPA and Occidental Chem Co., which is essentially the Diamond Shamrock Co. under a new name. The settlement forces the company to pay to clean up the Lower Passaic River and the outline of what is expected of them is outlined in the Statement of Work, Appendix B. These documents will be extremely useful in writing my paper because the cleanup is still ongoing and this is one of the most recent developments in the cleanup effort, being from 2016. I will be able to compare what the cleanup work entails with what has been done so far and how effective it is. It also outlines future plans, and because this settlement is binding, the Occidental Chem Co. will have to continue cleaning up long after my paper is complete. It is the most relevant document to me now in terms of what work is being done to protect the environment and what the overall outcome will likely be.

Secondary Sources:

Jones, N. Scott. “The Selected Remedy Is the Most Environmentally Protective Solution for the Diamond Alkali Superfund site. (Cleaning Up Newark: Rebuilding for the Twenty-First Century).” Seton Hall Law Review 29, no. 1 (December 22, 1998): 27–36.

This source is an article from the Seton Hall Law Review that gives an overview of the history of the site and what was happening with the cleanup until 1998.

This source will assist me in writing about the cleanup process until 1998. It gives a clear chronology up to that time and discusses various steps that I was not able to find in other sources. Such steps include the removal of soil from the surrounding areas in 1984 and 1985 and in September of 1995, the team working at the site undertook an “Accelerated Work Plan”. While much of the information in this article can be found by sifting through primary source documents, this article helps fill in the blanks I was encountering and allows me to better understand the cleanup process, which I will be writing about in detail.

“DIAMOND ALKALI CO. Cleanup Activities.” EPA. October 20, 2017. Accessed March 10, 2019. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0200613.

This source is a page from the EPA website regarding the cleanup activities at the Diamond Alkali site.

This source will be helpful to me in writing the part of my paper dealing with the cleanup between 1998 and 2014. I have found little information on that period and the page explains what happened following the implementation of the interim remedy and the settlement with OCC in 2016. On of the major things mentioned was the dredging and processing of sediment from the Passaic River between 2008 and 2012, in an operation known as the “Tierra Removal”. The page also provides information on the Lower Passaic River Study Area, which is where most of the cleanup is still going on. It will be useful in addressing the current state of the cleanup effort and the future.

Image Analysis:

Image Analysis of a Protesting Family

The Diamond Alkali plant, also known as Diamond Shamrock, was located at 80-120 Lister Ave in the Ironbound section of Newark, NJ. It is widely known as a producer of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was an extremely toxic herbicide used for clearing the jungles of vegetation so the Viet Cong could not hide and ambush US troops. It is linked to cancer and birth defects among the Vietnamese population as well as troops that served there. A by-product of the manufacturing process of Agent Orange, dioxin, was discovered at the abandoned Diamond Alkali plant in the summer of 1983. It is an extremely toxic substance, resulting in the area being immediately quarantined. Upon testing the soil and groundwater, the EPA found that there was dioxin contamination in both, and it had been dispersed throughout the Ironbound section of Newark by truck tires. Protesters took to the streets demanding action and answers as to why this was ever allowed to happen. The image I have chosen depicts protesters in action, focusing on a mother and her two children holding signs, with other protesters in the background. All of their signs bear confrontational messages directed at Diamond Alkali. Protesters like them played a large role in getting the Ironbound cleaned up through their activism. This image shows that the dioxin affects the entire community, particularly the children, but also their fathers who may have been exposed to Agent Orange while at war, or as workers at the plant.

Children were victims of the dioxin exposure just as the adults were, and they were equally important in the protests to clean up the Ironbound. Among the first things to catch my eye when viewing the image were the woman with a doll that was holding a sign and the two children in the foreground, each holding a large picket sign themselves. While the doll was not a real baby, it was representative of one. Its purpose was to give a voice to babies through the writing on its sign, as they were affected by dioxin more than anyone. Being that babies are still developing, exposure to dioxin at such an early stage would have likely caused severe medical problems that would have manifested themselves in childhood. The babies might have even suffered prenatally from the dioxin affecting their mothers’ bodies. The effects of dioxin on the young and unborn cannot be understated.

The two children standing in the foreground are likely siblings and belong to the woman holding the doll. Each holds a picket sign with a confrontational message directed at Diamond Shamrock (Alkali). On the left is a boy about eight to ten years old and his sign says, “Diamond Shamrock WHY did You Hurt my DADDY and ME?”. His sister stands beside him and looks to be about the same age. Her sign says, “Diamond Shamrock Why are you Killing our Dads?”. It was likely Diamond Alkali did not care much about the children any more than the adults or they would have been more careful with the disposal of waste, however the children were most likely present at the protests and in this picture for publicity purposes. When children are affected, it prompts more calls for action, so children were probably instrumental in getting the Ironbound cleaned up. Their signs directly implicate Diamond Alkali as the cause of the dioxin contamination and make it clear that they are solely to blame. Pressure from the children at the protests gained power if the picture was made public since it tugs at peoples’ emotions and makes them more likely to take a stand on the side of the protesters.

Like the children, another group suffering from dioxin exposure were the men of the community. When taking this picture at face value, it is clear that whole families were affected by the dioxin, and while there was only one man in the picture, the children’s signs ask Diamond Alkali why they were hurting their fathers as well as themselves. Looking deeper, it is interesting that their signs specifically call to mention their father, who may have simply been another member of the community like them, but he could have been a plant worker who was exposed while working at Diamond Alkali. Also likely is that he may have been a Vietnam veteran exposed to Agent Orange while overseas. Their father is not in the frame, and this leaves room to wonder where he is. Perhaps he is hospitalized as a result of exposure to dioxin, or perhaps he was simply unable to attend the protest. However, he is mentioned on their sign, and again children can be powerful weapons when it comes to activism. The public is more willing to listen to a child than an adult, and this translates to pressure on Diamond Alkali to help contain and remove the dioxin. They are protesting on behalf of their father, and would likely be more effective than him, especially if he was a Vietnam veteran, since the public attitude toward them was unfavorable. Many believed the war was unjust and the media did not help the military’s public image.

The dioxin contamination in the Ironbound was unfortunately not a unique occurrence. Months before the discovery of dioxin at the Diamond Alkali plant, the EPA began discussions to buy out the land in Times Beach, Missouri, due to dioxin contamination. However, the dioxin can be traced back to the early 1970s when a waste oil company obtained contaminated oil from a plant in Missouri producing Agent Orange. It was not until 1983 that relocation began. In popular culture, the last episode of M.A.S.H. aired in February of 1983, setting the still unbroken record for the most watched television episode at an estimated 125 million viewers. Clearly the Vietnam war was still on everyone’s mind in the 80s, and it would not be going away any time soon for the people of Newark as dioxin was discovered at Diamond Alkali a mere three months after the episode aired.

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews:

This interview of Nancy Zak was conducted on April 5, 2019 at the Ironbound Community Corporation, located in Newark, NJ. Nancy was directly involved in the activism against dioxin in the Ironbound and currently works at the ICC to continue helping her community with other troubles it faces.

Video Story: