Newark’s Anheuser Busch: The Unsuspected Leader In Sustainable Brewing Practices

by Patrycja Dziewa

Site Description:

Due to my involvement in the American craft beer industry, working on a paper related to beer is interesting and a great way to say focused and interested on my topic. Getting into the industry, domestic premium beer, such as Bud Light and Budweiser are deemed “not real beer” and therefore big breweries such as Anheuser Busch are seen as The Grinch of the craft beer industry. This bias is what sparked research into how the Anheuser Busch Brewery in Newark remains relevant and in business now that most breweries focus on sustainability. Turns out the brewery in Newark utilizes solar panels as well as recycles and donates their spent hops. These practices are now more common in the industry. In my paper I’ll be tracking past brewing practices, in the 1950’s when Anheuser Busch moved to Newark, during the 70’s and 80’s when beer counter culture sparked a craft beer revolution, and how breweries, local, such as Flying Fish or River Horse, work in unison with large, national breweries such as Anheuser Busch to positively impact the environment.

A couple of questions I’d like to explore are: What brewing practices in the middle to late half of the 20th century look like and how did people view the future then? How has sustainability become embedded into beer culture and industry? What was it about Newark that brought Anheuser Busch over? Breaking my paper up into three parts entails a section about brewing practices in the middle to late 20th century and the environmental injustices involved, another section about how at the same time there was a rumbling counter culture among homebrewers who financed their own breweries, and a final section about current sustainable practices in smaller local breweries and how that kind of branding has pressured a large brewery such as Anheuser Busch to also turn to sustainability to remain on the market.

Final Report:

I Remember My First Bud Light

Growing up around beer and various parts of the beer industry, it was only natural I’d end up working with beer. Being around the American craft beer industry, which comprises primarily microbreweries that make no more than 15,000 barrels of beer annually, always meant that macro-breweries, like Anheuser Busch, were to be disliked. Macro-breweries recipes were devalued because they were considered too bland and due to their production size, they could not be safe for the environment. Making them the craft beer industry’s arch nemesis. What this paper originally set to find out was just how evil Anheuser Busch was and to quantify all the terrible “things” it has done to the environment.

After weeks of digging, and buying my first Bud Light, something I swore I’d never do, that stigma has been busted. Anheuser Busch is not the evil macro-brewery it has been set up to be. Across Anheuser Busch’s breweries, they have solar panels, donate spent grain to become cattle feed, recycle both bottles and cans, and largest surprise, Anheuser Busch is the “largest user of bio-energy recovery systems that convert wastewater from the brewing process into a renewable fuel.”[1] Having the Anheuser Busch’s Newark brewery so close, it became a personal mission to prove that Anheuser Busch is not as bad as it’s portrayed among indie, craft breweries; that it too can be a leader in sustainably and that it’s production size does not interfere with the brewery’s environmental sustainability and strides. I stumbled upon a lot of videos about what craft beer stands for and was surprised to find that Anheuser Busch does just as much community give-back as many microbreweries do. With humble beginnings, Anheuser Busch was once a small, immigrant ran microbrewery in Missouri, and it has not forgot its roots even as its become the giant brewery that its is today. Below is a video essay stitching together the videos I found, shedding some light on the true nature of Anheuser.

As I dug in the archives several questions kept popping into my head, including, why Anheuser Busch was painted as an enemy by the craft beer industry? And what made them sustainable compared to what some microbreweries are doing? More specifically to Newark, I was curious about when Anheuser’s Newark brewery moved into the city, what its beer scene was like at that point in time, and how it fit into the city. Following questions revolved around the brewery’s effect on how its operations changed Newark in regards to water, waste, and recycling? Finally, how does its operations change tell a story about contemporary craft beer culture?

In order to answer these questions, I dug into different types of sources: both from social media and academic. The combination between social and scholarly sources made this search an anthropological study, looking into marketing and the relationship between brewery and consumer. There is a cultural history in the beer industry which is based around advertising and packaging. A lot of sources are from breweries websites and social media, primarily Instagram. Sources are also pulled from beer packaging, blogs, non-academic articles, and conversations with employees at micro-breweries, usually over a pint or two. The scholarly sources, making up the bulk of the historical information on Anheuser Busch and brewing in the 1950’s, come from beer-related journals and articles. Together, the combination of both social and scholarly sources emphasis the change over time which launched Anheuser-Busch to the forefront of sustainability in the American beer market.

After a brief history of Anheuser in Newark, this paper will follow the brewing process, first looking at issues around water, then ingredient waste, and finally recycling. Water being the most important ingredient in the brewing process, it is the most used and most wasted. Ingredient waste follows the reuse of grains and how carbon used by trucks moving ingredients across the country, adds to a brewery’s environmental damage. Finally, once an item leaves a brewery, whether a glass bottle, aluminum can, or the paper carrier it is in, it also adds to possible environmental damage. Under these three categories, it will be looking at both Anheuser Busch, in general, as well as various well known microbreweries from the United States. Pressure from microbreweries, and developing craft beer culture, pushed and persuaded a macro-brewery such as Anheuser Busch to reach and maintain sustainable practices in order to compete with the consumer market and the industry, as well as highlight the importance of environmental justice as it pertains to renewable practices associated with water, ingredient waste and recycling.

The History and Cultural Impact of a Brewing Giant in Newark, New Jersey

Originally hailing from St. Louis, Missouri, Anheuser Busch moved into Newark in 1951, and thus began the rapid decline in the beer industry within the city. Anheuser moved up north in 1951, in order to brew beer and ship it shorter distances for their customers in the North East.[2] The brewery transplanted into Newark after World War II, when the city was still an industrial powerhouse, making it the ideal location for large, mainly mechanized, brewery. Most industries experienced their highest levels of productivity and at that time, success in the city tended to come with a price: degradation to the environment.[3] As it concerned Anheuser Busch, this did not seem the case, but their public involvement in sustainability did not come until later.

When Anheuser Busch moved up in 1951, it began the shutdown of all other beer production in Newark, to which it has not yet replaced. One of the most well-known beers coming out of Newark was produced by the Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company. The 1950s saw consolidation in the brewing industry, and macro-breweries like Anheuser Busch “squeezed out market share.” A decade later, as stated by Newark Business, a site dedicated to the celebration of industry leaders in post-riot Newark, the “Krueger brewery drained its tanks of their last trickles of beer and closed its doors for good.”[4] Relentless competition added the Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company to its long list of victims, along with P. Ballantine and Sons Brewing Company. By the mid-1960’s the brewery was already in decline, but managed to stay in the industry a decade longer than Krueger. Ballantine, once a renowned brewery from Newark, New Jersey, “with a capacity of five million barrels a year, the brewery [was] one of the largest in the country,” as per Ronald Sullivan’s 1972 article “Newark Losing Ballantine Plant” from the New York Times. Sadly in 1972, it closed its doors, and was absorbed by Falstaff Brewing Corporation, which moved the brewery out of Newark, devastating many Black and Puerto Rican families of a local business and jobs.[5] Anheuser Busch grew with Newark as it continued to become a metropolitan, industrial powerhouse, monopolizing the brewing scene in the city.

Source: http://www.beerhistory.com/library/holdings/krueger.shtml

The image of Anheuser Busch as wasteful industrial polluter is evident in Newark’s cultural history. For instance, one perspective of the Anheuser Busch brewery in Newark was captured by an artist’s oil painting. Valeri Larko’s painting from 1999 suggests the Anheuser Busch Brewing plant is over-glorified as a mecca of industrialization — producing a landscape which is riddled with abandonment, and environmental degradation (See painting below).

These central most dominant figure in the painting, is the mountainous landscape, made up by the red-brick Anheuser Busch brewery in the background. The brewery is highlighted by its color contrast, being the only figure, which is reddish-brown against a gray sky and among green foliage. Larko described seeing the distilling towers as “the yellow stacks of a factory, transformed by sunlight … [which] remind [her] of a cathedral.”[6] This is no coincidence given the religious iconography in a cemetery, but it also speaks to the worship of big production and industry in Newark. The stark white cross with a crucified Jesus juxtaposed on the right side of the brewery, at about the same size, suggests this. The big white cross is intentionally contrasted against dark green foliage in order to highlight the brewery’s importance and suggest there is a similarity between the martyrship of Jesus and the way big industry has given Newark its name across the globe. Larko’s view was not unique at the time. The Anheuser Busch Brewery’s shadow is perhaps a visual metaphor for the brewery being a ghost from a different, more momentous era, which is why this particular painting is located in a cemetery, among tombstones.

The issue of abandoned areas in Newark was not something Larko criticized on her own. Newark was becoming a ghost town in the 1990’s — the abandoned homes and lots in Newark pushed residents out, and residents, such as those in Karen Yi’s NJ.com article “This N.J. Block is Dying, One Abandoned Property at a Time,” “can’t take this anymore.” According to Newark’s abandoned property registry, in 2017, there are more than two thousand abandoned or vacant properties in the city.[7] It is perspectives such as Larko’s which add to the negative stigma around macro-breweries. It seems to lose the fact that breweries such as Anheuser Busch were also once small, microbreweries, but through popularity, price points, and industry merges, it has gained a lot of recognition and there is something to be said about the impressiveness to create a beer that that tastes the same every time it’s brewed, which is not a small feat. Larko’s environmental angle is moot as the 90’s were a big time in Anheuser’s large, corporate push towards sustainability.

“It’s The Water”[8]

The brewing industry has always been conscious about the importance of clean water. Since breweries used water for both brewing and cleaning, clean-water practices have always been the cornerstone of any brewery’s operations plan and location. Historically, a brewery has always been placed near a body of water, as water takes up ninety percent of the brewing process. As the trade journal The American Brewer explained in a 1941 advertisement titled “Dealers in Malt and Hops” a “very good water supply” was a key ingredient to any brewery’s net worth.[9] This does not come as a surprise when one realizes most of America’s breweries are located along the coastal states.

Wastewater at a brewery, whether from brewing or clean up, may be “discharged in several ways including the following: (1) directly into a waterway (oceans, rivers, streams, or lakes), (2) directly into a municipal sewer system, (3) into the waterway or municipal sewer system after the wastewater has undergone some pretreatment, and (4) into the brewery’s own wastewater treatment plant.” The disposal of untreated or partially treated wastewater into bodies of water can create potential or severe pollution problems since the “effluents contain organic compounds that require oxygen for degradation.”[10] Anheuser Busch’s water, comes from the Passaic River, where it undergoes mass filtration and purification in order to maintain a high standard of water quality. Aloha Beer Co., a micro-brewery located in Hawaii, took that concept one step forward by using ocean water to create their own natural salt to add to a salty beer style, known as a gose.[11] Due to its large importance in the beer-making process, and the flavor of one’s beer and its sanitary importance, it is safe to assume all breweries maintain a very high standard of care with their water supply.

Not only is Anheuser Busch located near the Passaic River, it is directly across from Newark International Airport. There are no sources to prove whether Anheuser Busch was directly dumping chemicals, wastewater or other debris into local water bodies. Nor is there information whether they were improperly filtering it and making consumers sick. However, the location on the Newark’s Anheuser Busch brewery poses other risks. Using the publicly funded and accessible Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, creating a one mile radius around the brewery, environmentally, the area around the Anheuser Busch Brewery tends to have very high levels in the categories of O-Zone, Hazardous Waste Proximity, and Wastewater Discharge Indicator. In the fields of Hazardous Waste Proximity, in this area, it is in a higher national percentile, 94th, compared to the state, 88th. On the other hand, in Wastewater Discharge Indication, this area, which is in the state’s 89th percentile, is locally producing more wastewater compared to the national average, which is in the 73rd percentile. The biggest fault with this data lies in the brewery’s proximity to the airport, which is undeniably a very large contributor to ozone harm, producer of hazardous waste, and wastewater. This proximity makes it difficult to specifically pinpoint the brewery as the sole cause of environmental degradation, but it could help explain why the brewery would want to push for a very sustainable facility.

EJScreen Data: One-Mile Radius Around Anheuser Busch Brewery

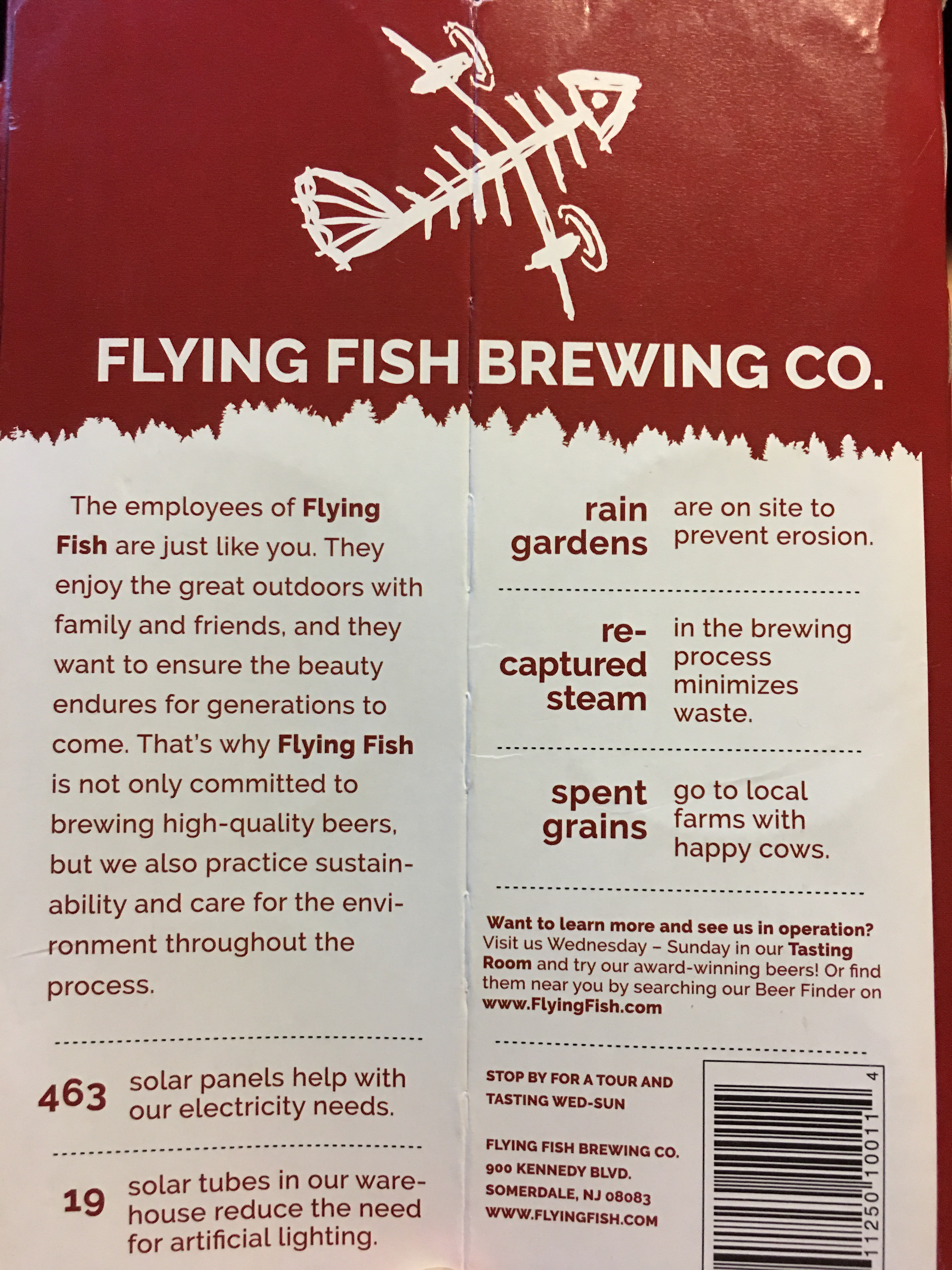

Many microbreweries were initially created with sustainability in mind, particularly in the ninety’s. One local New Jersey brewery, Flying Fish, located in Somerdale, originally started as a virtual microbrewery online, connected people and investors through their large ideas about brewing and sustainability. When it came time to create a large scale brewery, reducing water and energy consumption was part of the plan. They installed a “brew kettle [which] recaptures all steam that would normally vent to atmosphere and create 1 gallon of hot water for every 5 gallons of beer brewed … other savings come from reusing process water for cleaning operations.”[12] They also created “rain gardens on site to prevent erosion.”[13] This is so much of their business model, they have this information along with other ways they practice sustainability on their six pack carriers and the cardboard boxes their six packs come in.

The ninety’s played a crucial part in craft beer history. The craft beer revolution picked up speed at this moment and just like Flying Fish, many breweries took sustainability to be an important part in their responsibly as a brewery, most likely due to the large quantities of water they would be using. Coincidently, this is the same time Anheuser Busch went public with their own sustainable goals. Although Anheuser Busch was not as outright about their sustainable plans for the future, in 2018, they published a projected 2025 plan, where by the end of that year, they would be the leaders of sustainability in the beer industry. Breaking the plan up into four areas, water stewardship being one of them: “100% of facilities will be engaged in water efficiency efforts; and 100% of communities in high stress areas will have measurably improved water availability and quality.”[14] Although there are still a few more years until they reach their goals, Anheuser Busch has creeping at the goals by spearheading a new campaign for clean ingredients in their beer, eliminating corn syrup from the recipe. Promoting beer as a natural product, further emphasized by clean ingredients, they believe it is a part of their responsibly to maintain a healthy environment. Apart from water, the cleanup and maintenance of spent ingredients is another large throw away product of the brewing process.

Grain and Carbon Dioxide: The Less Than Dynamic Duo

Microbreweries have made issues surrounding by-product elimination and ingredient sourcing as their biggest sustainable problem. Ninety percent of beer is created with water, the remaining ten percent is a precise and sometimes experimental combination of malt, hops, and yeast. Many breweries now use pellets of dried hops because they transport a lot better and remain fresher longer. Some styles, particularly in India Pale Ales, brewers will opt for fresh hops, in which the entire flower will be used in the brew, but these have a short shelf life. Once hops are used in a brew, it will used a few times more, as long as it maintains its flavor. In an interview with an employee at the Brooklyn Brewery, a well know microbrewery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NYC, he mentioned the brewery uses its hops as often as possible and only after it loses its flavor integrity, meaning it will be used multiple times, they will throw it out, as it is not edible. However, the brewery will donate their spent grain to local farmers.[15] Spent grain is mash left over from the use of barley, wheat or other grains to add flavor and color to beer. These grains remain in the brew for a long time, creating a mash, typically creating a delicious oatmeal scent which travels across the brewery. This mash cannot be used again, as it is boiled until all the flavor is extracted.

These grains make incredible feed for farm animals and are given away in large bins full. Not only for farm animals, but some startups are trying to use spent grain to create plant based protein for vegetarians and vegans. In 2017, Canvas, a beverage start up backed exclusively by Anheuser Busch InBev, this group took spent grain and turned it into a sustainable ingredient.[16] Anheuser Busch donates their spent grain as well, but taking that a step further they are trying to cut back on carbon pollution which is synchronous with transporting grains from farms to breweries and beer to markets. Anheuser Busch added the lowering of carbon emissions, and switching to cleaner trucks, in order to bring in ingredients and deliver their beer nationwide, as one of the four main aspects in their 2025 sustainability plans.

Most of America’s beer ingredients, primarily hops, are grown on the west coast, in California and Washington, making added carbon emissions from transporting across the nation potentially hazardous. There are separate corporations who grow, dry, and pack dried hops into pellet-shapes for distribution across the nation. This does not seem like a problem for breweries in which are located near those farms and distributors, but breweries on the east coast have turned to local farmers and other breweries across the nation have started their own farms in order to cut down on carbon and other truck emissions. In the case of Newark, the city is already jam packed with truck traffic on the highway and in the neighborhood leaves Anheuser to take a stand against all the pollution they aid in creating, as Anheuser Busch’s Newark brewery brews beer for the entire Northeast. Rogue Ales and Spirits, located in Oregon, used their social media platform to inform the public about their Rogue Farm, which “grows more than a dozen ingredients for [their] beer, spirits, cider and soda [including:] ten varieties of hops, two varieties of malting barley, rye, pumpkins, marionberries, jalapeños and honey, [which are used] to create [their] craft beverages.”[17] The Farm is located less than one hundred miles away from the brewery, making it a lot shorter of a route from Washington or California, and gives them the flexibility to experiment with flavors, which is an element in craft brewing.

Besides owning their own farms, some breweries opted for collaborating with farmers in their area in order to reduce travel length. Stone Brewing began a Farm to Can series in 2019. The first beer of the series includes hops grown in Moxee, Washington, presenting itself loud and proud on the packaging,[18] This type of marketing aids both the brewery and farm. In the case of Troegs Independent Brewing, located in Hershey, Pennsylvania, when it came time to brew LolliHop DIPA, they enlisted the help of Dustin and Cody Musser of Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, fifteen minutes away from the brewery, to grow what Troegs called the “backbone of our new Double IPA LilliHop.”[19] They believe it’s important to keep craft maltsters in Pennsylvania, to help them stick around and thrive.

Due to its popularity and large effect on one’s carbon emissions, Anheuser Busch, who has multiple breweries across the United States, fittingly have their “own hop farms in Bonners Ferry, ID, and the Hallertau region of Germany.”[20] Anheuser Busch also owns a mill in Arkansas as they are famous for adding rice into their recipe. In order to transport all of this, they said they are committed “to reduce the environmental impact of its supply chain, [furthermore] Anheuser Busch last year committed to purchasing 40 Tesla electric powered trucks.”[21] Feeling the heat about growing and using one’s own resources got to Anheuser and influenced their idea about how they plan on expanding it. Owning a farm or collaboration with local famers not only stimulates the local economy, but it also reduces the carbon output of a brewery. After beer is bottled or canned, how it gets delivered to the consumer extends its sustainable and reusable life.

Bottles Versus Cans: It’s More Than About Freshness

The argument between recycling of bottles and cans as well as the recycling and reuse of boxes and carriers are an extension of a breweries investment into a plan towards sustainability. The history of the beer bottle’s importance is that it once signified a relationship between two artisans: a glass blower and brewer. According to a site aptly named “All About Beer,” glass bottles typically fit “the traditional spectrum of clear, green and dark amber glass.” Some breweries molded special bottles with their names or special designs sculpted onto them, for example New Belgium. Others used bottles for specific beers, especially wheat beers such as a hefeweizen, where the glass bottles have bulbous necks to collect unfiltered particles of wheat as the beer pours. A lot of breweries will release 750 ml specialty brews in glass bottles, dishing out a little extra money with the idea that they could charge a little more due to the use of glass. Budweiser remains both cans and bottles in order to serve their very wide demographics. Budweiser and Bud Light in bottles suits an older clientele while Bud Light Platinum and Bid Light in cans tends to be a choice by a younger generation. Most brewers choose brown bottles, because they let in the least amount of ultraviolet light, beer’s worst enemy, which negatively affects the alpha acid in hops, resulting in light-struck, off flavor, commonly experienced as “skunked.”[22] Moving away from the cost of glass bottles, the trend in the micro brewing industry has been a shift into canning beer.

Many contemporary craft microbreweries have been using cans, some are switching their operations to all cans. The idea here was that cans are infinitely recyclable and light cannot penetrate them. They are also cheaper for breweries to buy, and transport a lot easier. Aluminum cans stack neater and one could fit a lot more into a truck than one could with bottles, therefore it lowers the amount of trips and carbon used to move trucks full of beer to distributors and warehouses. In Anheuser Busch’s 1991 commercial, they advertised themselves as the leaders in recycling. As of 2019, it is unknown whether Anheuser Busch will switch to strictly cans or bottles, as they have too many consumers who prefer one or the other. In their 2025 plan, all their breweries will be over 99% recyclable, but it’s unclear what exactly this entails.

Besides bottles, Anheuser Busch is part of an initiative to make carries and their cardboard recyclable. Bart Elmore of The Business History Review, spelled out the timeline of how large corporations such as Coca Cola and Anheuser Busch started “green campaigns” in the fifties largely due to consumers uneasy attitude about the waste leftover after one’s bought and consumed products from these big businesses. According to Elmore, “for the soft-drink, brewing, and canning industries, the promise of recycling became a powerful weapon for combating mandatory deposit bills and other source-reduction measures in the 1970s and 1980s.”[23] This also aids to explain why sustainability and eco-consciousness is embedded in contemporary breweries ideologies. Many microbreweries are associated with forestry stewardships, using recycled paper to make products. Flying Dog Brewery has adapted their Raging Bitch cardboard boxes to use less ink, this makes the box a lot safer to recycle and decompose. All in all, Anheuser Busch is paving the path toward running the show as it pertains to brewery sustainability, but it still has a few things to learn from other breweries.

Anheuser Busch as Tomorrow’s Sustainability Leader

Anheuser Busch’s future, after the nineteen-nineties relied on adapting and changing its sustainability approach in order to remain relevant and competitive in the market. All of this change happened while microbreweries already instilled sustainability and community give-back into their business’ framework. From the installation of solar powered panels, to donating fresh, filtered water to areas of America that need it, Anheuser Busch has not been the terrible, corporate brewery I was made to think it was. That stigma must have picked up when more and more breweries were claiming their Independent Brewers certification. Independent or not, Anheuser is pushing the bounds for what the future of brewing could be, particularly with its sustainable goals. It still unclear what they do with their wastewater, but it is fair to say that they are most likely not contaminating any other bodies of water, as there is no evidence to prove it and fresh, clean water is sacred to brewing. From water to grain and carbon, Anheuser’s backing of experimental ways to recycle grain is fascinating and exciting. There are companies that make dog biscuits out of spent grain, but Anheuser’s investigation on the human benefits of ingesting spent grain could open another market. Finally, the debate about glass bottles or cans will not be answered by anything in Anheuser Busch’s 2025 plan, but it will make its way back onto the table as soon as more and more indie craft breweries only can their beer.

The stigma around Anheuser Busch will be broken down as their sustainability goals are met, propelling them into the foreground, as industry leaders. There is something to say in the mastery of creating a mass produced beer which tastes the same every time. It’s also easy to forget that yes machines spin and heat up the beer, but it is brew masters watching, tasting, and providing the expertise to get the years old recipes exactly right each time. It does seem like a lack of ingenuity in that they do not have has wide of a flavor portfolio as many microbreweries do, but some might say, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” So I will raise my sixteen ounce pour of Budweiser, and propose a toast to Anheuser Busch: to keep on the good work of environmental consciousness, unexpectedly ruling the brewing kingdom as the sustainable “King of Beers.”

[1] Bocis, Gene R., Jr. Sustainability Session. Proceedings of 2012 World Brewing Congress. Accessed 2012. https://www.mbaa.com/meetings/archive/2012/Proceedings/pages/220.aspx.

[2] No particular source is this information pulled from, it is the operation procedure for many macro-breweries. By moving into key locations of the country, they reduce the cost of shipping from their flagship brewery.

[3] This was just typical of many industries at the time, workers health, research into material’s effect on the Earth and dumpsite had not yet determined laws and practices for large-scale production factories. It is also before the Newark Riots of 1967, which lead to the decline of Newark as a city.

[4] Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://newarkbusiness.org/brewers/kk/krueger.php.

[5] Special, Ronald Sullivan. “Newark Losing Ballantine Plant.” The New York Times. March 04, 1972. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/03/04/archives/brewery-is-sold-to-falstaff-which-will-keep-brand-ballantine-sold.html.

Ballantine was one of the largest businesses in the Ironbound district which employed Black and Puerto Rican community members. When Falstaff assumed Ballantine, they offered to move former employees to one of their locations, but the closest one was in Rhode Island, and that was simply out of the question for their former brewery employees. It is unclear whether they went to work for Anheuser Busch on moved onto other jobs.

[6] Urban and Industrial Early Paintings. Accessed March 22, 2019. http://www.valerilarko.com/valeri_contents/galleries/industrial/industrial_paintings.html.

[7] Yi, Karen. “This N.J. Block Is Dying, One Abandoned Property at a Time.” Nj.com. September 03, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2019. https://www.nj.com/essex/2017/09/newark_abandoned_properties_pushing_longtime_homeo.html.

[8] Olympia Beer’s slogan and claim to fame was the freshness and purity of their water supply near Olympia, Washington.

[9] “Dealers in Malt an Hops” The American Brewer 74, no. 06 (1941): 68.

[10] Simate, Geoffrey S., John Cluett, Sunny E. Iyuke, Evans T. Musapatika, Sehliselo Ndlovu, Lubinda F. Walubita, and Allex E. Alvarez. “The Treatment of Brewery Wastewater for Reuse: State of the Art.” Desalination 273, no. 2-3 (2011): 235-47. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2011.02.035.

[11] Morgankaya. “This Craft Beer Is Brewed with Ocean Water.” Frolic Hawaii. October 18, 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.frolichawaii.com/stories/craft-beer-brewed-ocean-water.

[12] “Sustainability.” Flying Fish Brewing Co. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.flyingfish.com/about/sustainability/.

[13] Flying Fish. Redfish IPA six-pack bottle carrier. Sustainability information on bottom of carrier. Purchased May, 2019.

[14] “Anheuser-Busch Announces U.S. 2025 Sustainability Goals.” Home. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/newsroom/20071/04/anheuser-busch-announces-u-s–2025-sustainability-goals.html.

[15] A few notes taken during a conversation and facility tour with employee Mike S. from Brooklyn Brewery in early October 2018.

[16] “Grain Gains: Canvas Spins Beer Byproduct into Plant-Based Protein.” BevNET.com. December 29, 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.bevnet.com/news/2017/grain-gains-canvas-spins-beer-byproduct-plant-based-protein.

[17] Farms. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.rogue.com/farms.

[18] Stone Brewing. Moxee Gold IPA six-pack can carrier. Front and bottle of carrier include advertisement for collaboration. Purchased May 2019.

[19] Instagram. @troegsbeer Posted March 24

[20] Brewing Process & Ingredients. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/about/brewing.html.

[21] “Anheuser-Busch Announces U.S. 2025 Sustainability Goals.” Home. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/newsroom/20071/04/anheuser-busch-announces-u-s–2025-sustainability-goals.html.

[22] “Critical Glass: The Enduring Power of Beer Bottles.” All About Beer. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://allaboutbeer.com/article/critical-glass-the-enduring-power-of-beer-bottles/.

All information in paragraph is from this source.

[23] Elmore, Bartow J. “The American Beverage Industry and the Development of Curbside Recycling Programs, 1950-2000.” The Business History Review 86, no. 3 (2012): 477-501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41720628.

Bibliography

“Anheuser-Busch Announces U.S. 2025 Sustainability Goals.” Home. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/newsroom/20071/04/anheuser-busch-announces-u-s–2025-sustainability-goals.html.

Bocis, Gene R., Jr. Sustainability Session. Proceedings of 2012 World Brewing Congress. Accessed 2012. https://www.mbaa.com/meetings/archive/2012/Proceedings/pages/220.aspx.

Brewing Process & Ingredients. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/about/brewing.html.

Brooklyn Brewery. Conversation had with Mike S. after facility tour. Early October 2018.

“Critical Glass: The Enduring Power of Beer Bottles.” All About Beer. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://allaboutbeer.com/article/critical-glass-the-enduring-power-of-beer-bottles/.

“Dealers in Malt an Hops” The American Brewer 74, no. 06 (1941): 68.

Elmore, Bartow J. “The American Beverage Industry and the Development of Curbside Recycling Programs, 1950-2000.” The Business History Review 86, no. 3 (2012): 477-501. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41720628.

Farms. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.rogue.com/farms.

“Sustainability.” Flying Fish Brewing Co. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.flyingfish.com/about/sustainability/.

Flying Fish. Redfish IPA six-pack bottle carrier. Sustainability information on bottom of carrier. Purchased May, 2019.

Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company. Accessed May 13, 2019. http://newarkbusiness.org/brewers/kk/krueger.php.

“Grain Gains: Canvas Spins Beer Byproduct into Plant-Based Protein.” BevNET.com. December 29, 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.bevnet.com/news/2017/grain-gains-canvas-spins-beer-byproduct-plant-based-protein.

Instagram. @troegsbeer Posted March 24

Morgankaya. “This Craft Beer Is Brewed with Ocean Water.” Frolic Hawaii. October 18, 2017. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.frolichawaii.com/stories/craft-beer-brewed-ocean-water.

Simate, Geoffrey S., John Cluett, Sunny E. Iyuke, Evans T. Musapatika, Sehliselo Ndlovu, Lubinda F. Walubita, and Allex E. Alvarez. “The Treatment of Brewery Wastewater for Reuse: State of the Art.” Desalination 273, no. 2-3 (2011): 235-47. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2011.02.035.

Special, Ronald Sullivan. “Newark Losing Ballantine Plant.” The New York Times. March 04, 1972. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/1972/03/04/archives/brewery-is-sold-to-falstaff-which-will-keep-brand-ballantine-sold.html.

Stone Brewing. Moxee Gold IPA six-pack can carrier. Front and bottle of carrier include advertisement for collaboration. Purchased May 2019.

Urban and Industrial Early Paintings. Accessed March 22, 2019. http://www.valerilarko.com/valeri_contents/galleries/industrial/industrial_paintings.html.

Yi, Karen. “This N.J. Block Is Dying, One Abandoned Property at a Time.” Nj.com. September 03, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2019. https://www.nj.com/essex/2017/09/newark_abandoned_properties_pushing_longtime_homeo.html.

Primary Sources:

“Dealers in Malt an Hops” The American Brewer 74, no. 06 (1941): 68.

This tiny snippet from The American Brewer periodical (volume 74, issue 06) from 1941, a year before the periodical ended, under the “Dealers in Malt an Hops” section, there is a classified advertisement for a brewery which has its own “very good water supply.” This periodical was found online, it was produced in America and seems to have been distributed across the country. This tiny advertisement emphasizes the importance to having one’s own water supply in the brewing industry. Even in 1951, when Anheuser Busch opened up its new facility in Newark, they too depended on their own water supply. Before the creation of a public supply of water, through local municipalities, breweries would be located near bodies of water for if inland, they would dig their own source of groundwater. This advertisement from the 1940’s not only demonstrates that public water was not used in the beer industry yet, but that brewers relied on finding their own source, which meant that water was the key source to a successful beer business but also depleted local water for everyone around the brewery. This source helps with the history of brewing, when Anheuser Busch opened up its plant in Newark, in 1951, it mostly likely also sourced a nearby body of water before the city had businesses pay for water. By draining their own resources, this damages the nearby environment. (https://digital.hagley.org/American_Brewer_74_06?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=995e513f45368d24a4b3&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=5&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=7#page/69/mode/1up)

Shotton, F. W. “Underground Water Supply Of Midland Breweries.” Journal of the Institute of Brewing 58, no. 6 (1952): 449-56. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.1952.tb06196.x.

This source is from the Institute of Brewing in the United Kingdom. Although far removed from Newark, it could be said that due to the publication’s large importance in the beer community, its research and findings could be general for brewing practices in the world. This institution, to this day provides the certification tests and information for brewers in the United Kingdom. All though from the other side of the Atlantic, information was most likely shared. This article deals with how midland breweries supply their groundwater for production. It explains the dangers of overusing their source in fear of creating hard ground. This source aids in explaining how breweries who were using their own water supply were risking harming the ground. This damage could have happened at or near AB Brewing around the time of its opening.

Brewery, Brooklyn. “Sustainability : Brooklyn Brewery.” The Brooklyn Brewery. Accessed March 10, 2019. http://brooklynbrewery.com/sustainability.

Brooklyn Brewery, one of the nation’s most popular keeps sustainability at the foreground of its operation. This source is directly from their website. This source came to mind after I had a direct conversation with one of the employees at the brewery. Their brewery had also sourced water from Upstate New York and they donate their spent malt (malt which cannot be recycled) to farms, as well as reuse their hops as much as they can. This source is only one example of how breweries today try to be green, and it’s much more than switching to LEDs. This source is no doubt a form of 21st century branding, therefore biased, but like the first source mentioned, both advertisements highlight the importance of sources and how one conducts their business at the time of its publication. In the first source, the importance was about being located near one’s own water source and in this advertisement, it is Brooklyn Brewery’s initiative to further sustainability at their facility.

Secondary Sources:

Palmer, John, and Colin Kaminski. Water: A Comprehensive Guide for Brewers. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2013.

This source is a book targeted at people in the brewing industry. It describes the water cycle and the process for cleanly reusing water. The brewing industries biggest environmental impact is in its large consumption of water and how it deals with cleaning and reusing it. This book provides an example of ideas and techniques breweries are using in order to produce environmentally-sound beer. Sustainability and constant improvement in regard to green production is entwined into beer culture, with this book in production, it is clear that the beer industry is aware of its negative impacts, especially in regard to water, and its strides to lower consumption as well as reusing water. This source fits into the later third of my paper which will deal with the current craft brewers culture and why a large brewery like Anheuser Busch would also switch to be more sustainable in order to appeal to the same consumers who do care about the sustainability of where their products come from.

Olajire, Abass A. “The Brewing Industry and Environmental Challenges.” Journal of Cleaner Production, 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.03.003.

This is a peer reviewed journal, accessed from the internet, which deals with the environmental challenges in the brewing industry. The brewing industry uses a lot of water and requires land for agriculture (malts and hops). This source will help me in the middle of my paper, the part which deals with the sort of counter culture which strives to create a sustainable brewing industry due to it’s in depth analysis of where sources are being used and in what quantities. This source also makes it very clear where all the water and wastewater is used in the brewing process, with a lot of graphs, easy to understand graphics, and number breakdowns that make this information very digestible.

Deaton, Jeremy. “America’s Craft Breweries Are on an Environmental Crusade.” Popular Science. August 16, 2017. Accessed March 10, 2019. https://www.popsci.com/craft-brewer-conservation-climate-change.

Although from a blog related to “Popular Science” due to beers high consumption, being one of the top five beverages consumed in the United States, its important platform puts it under a light to be different and more sustainable than other beverage facilities, such as those producing soda or bottled teas. This source will be used alongside my primary sources relating to how examples of how breweries such as Brooklyn Brewery or River Horse Brewing donate their hops and reuse their water. It’s not an individual phenomenon, but a large movement, if not already embedded into current craft brewing culture. The person I spoke to at Brooklyn Brewery mentioned we are living in a Craft Brewing Renaissance, which would bring hope that sustainability in one’s brewing facility is not only better for the environment, but better for the workers and consumers.

Image Analysis:

Exploring the world of brewing in Newark post the 1950’s proves to be very difficult. The opinions of the mass-producing machine that is Anheuser Busch, the general over-industrialization of the neighborhood, from people in Newark, however, is plenty. A painting done by artist Valeri Larko in 1999, titled “Mt. Olive Cemetery” produces one of the opinions about Anheuser Busch, and industrialization, at the tail end of the 20th century. Her painting suggests Newark, or the specifically the Anheuser Busch Brewing plant, is over glorified as a mecca of industrialization, producing a landscape which is riddled with abandonment, and due to those previous assumptions, it also harms the environment.

These central most dominant figure in the painting, which is produced of oil on linen, stretching forty-six inches in width and twenty-six inches in height, is the almost mountainous landscape in the background. It is made to be important due to its color contrast, being the only figure, which is reddish-brown against a gray sky and among green foliage. Larko describes seeing the distilling towers and “the yellow stacks of a factory, transformed by sunlight … [which] remind [her] of a cathedral”.[1] This is no coincidence given the religious iconography in a cemetery, but it also speaks to the worship of big production and industry in Newark. The stark white cross with a crucified Jesus juxtaposed on the right side of the brewery, at about the same size, suggests this worship. The big white cross is intentionally also contrasted against dark green foliage in order to suggest the similarity between the martyrship of Jesus and the way big industry has given Newark its name across the globe, when it was once one of the busiest ports on the East Coast of America.

Valeri Larko was initially drawn to this space because at the time of this painting, she was focusing her work on abandoned places in New Jersey. She has said at this time of her artistic career, she “often approach this subject matter [abandoned spaces] with a sense of irony and humor”[2] With this she means that the areas of Newark which were once rich with business and industrial glory, are now stand-alone areas of the city’s landscape. These places, like the Anheuser Busch Brewery, are perhaps like ghosts from a different, more momentous era, which is why this particular painting is located in a cemetery, among tombstones. The issue of abandoned areas in Newark was not something Larko criticized on her own. Newark is becoming a ghost town, the abandoned homes and lots in Newark continue to push residents out, and residents, “can’t take this anymore”.[3] According to Newark’s abandoned property registry, in 2017, there are more than two thousand abandoned or vacant properties in the city. Properties with no legal occupants for six months are considered vacant; those in need of rehabilitation, behind on property taxes or threatening community safety are defined as abandoned.[4] Residents are fed up with the constant hike in taxes especially when their tax money does not warrant efforts to clean up the city. The theme of abandonment, in the painting, is evident in that the Anheuser Busch Brewing facility is the only complex in the background’s landscape. Although it is not abandoned, and has been in business in Newark since 1951, it stands alone on a large lot. There is a very intentional lack of humanity and Larko playfully suggests, “two rusted tanks take on a human quality as they lean together in an ancient embrace,”[5] as if the massive structure itself has engulfed human-like qualities.

It is very hard to miss the large plumes coming out of the stacks of the Anheuser Busch Brewery in the painting. They are large and presented as very thick due to their lack of transparency throughout. Being a Realist artist, Larko does not add fluff or additional emphasis to her painting. Therefore, it would be true to believe the smog coming from the brewery was indeed thick at the time, being comprised of the release of gaseous byproduct, usually steam, during the brewing process. There is also a lack of foliage and anything green alongside the brewery. All of the trees are contained in the empty cemetery. The author of an article about Larko’s gallery opening in 2010 described Larko’s pieces of the time, as or years after, as a commentary on how “we live amid tomorrow’s junk today, and Larko’s paintings predict the place where our culture will soon arrive.”[6] Producing art in the late 20th century with themes about the mistreatment of the environment, whether through pollution or the increase of abandoned spaces, “Valeri Larko paints rusted distilling towers, ruined industrial interiors and sprawling piles of discarded refrigerators, computer monitors or car mufflers, all of them dinged or stained or rotting like discolored bruises, and leavened only by the occasional patch of blue sky.”[7] This gloomy idea of what the future holds if we continue these over-industrialized practices was what inspired many of Larko’s paintings, and “Mt Olive Cemetary” was not an exception.

The development of an industrial ghost town presented by Valeri Larko’s painting “Mt Olive Cemetary” produces a bleak image of the future of Newark as experienced by an artist in 1999. These key elements in the painting resonate with how Anheuser Busch, had to change their branding strategy and how they produced in order to compete with smaller, sustainable breweries, and the developing beer community’s culture in America. Current beer culture puts sustainability at the very core of their business, some breweries such as Flying Fish started operating with sustainability in mind as soon as their began brewing in the nineties. Overall, in postwar United States, specifically at the turn of the century, this painting suggests the need for change and social action in areas like Newark where issues of environmental damage and landscape abandonment are ever present.

[1] Urban and Industrial Early Paintings. Accessed March 22, 2019. http://www.valerilarko.com/valeri_contents/galleries/industrial/industrial_paintings.html.

[2] ibid

[3] Yi, Karen. “This N.J. Block Is Dying, One Abandoned Property at a Time.” Nj.com. September 03, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2019. https://www.nj.com/essex/2017/09/newark_abandoned_properties_pushing_longtime_homeo.html.

[4] ibid

[5] Urban and Industrial Early Paintings. Accessed March 22, 2019. http://www.valerilarko.com/valeri_contents/galleries/industrial/industrial_paintings.html.

[6] Staff, Star-Ledger. “For Valeri Larko, New Jersey’s Declining Manufacturing Sites and Salvage Yards Make a Fertile Landscape.” Nj.com, Nj.com, 2 May 2010, http://www.nj.com/entertainment/arts/2010/05/for_valeri_larko_new_jerseys_d.html.

[7] ibid

Data Analysis:

Analysis of Gathered Data from EJ Mapper

Newark, being the diverse city that it is, hides the most unfortunate results of our consumeristic ways of life. The city is home to low income many people of color who have to live in areas of mass environmental injustice and it affects their way of life and will affect their family’s lives for years to come. The location of the Anheuser Brewery is a pivotal in its contribution to the environmental degradation at least in a one mile radius around the facility.

Environmentally, the area around the Anheuser Busch Brewery tends to have very high levels in the categories of O-Zone, Hazardous Waste Proximity, and Wastewater Discharge Indicator. In the areas of Hazardous Waste Proximity, in this area, it is in a higher national percentile compared to the state. On the other hand, in Wastewater Discharge Indication, this area is locally producing more wastewater compared to the national average. The biggest fault with this data lies in the brewery’s proximity to the airport, which is undeniable a very large contributor to ozone harm, producer of hazardous waste, and wastewater. This proximity makes it difficult to specifically pinpoint the brewery as the sole cause of environmental degradation, but it could help explain why the brewery would want to push for a very sustainable facility especially in regards to water, carbon, and ingredients waste.

Demographically, this area hits very high percentiles, locally and nationally, in areas of the demographic index, minority population, low income population, and less than high school education. The area. It also includes a wide range of ages from infants to people over sixty-five. This area is home to a lot of families, especially ones with very young children. Across the board, this area is heavily populated with low income minority families, who have young children, and less than a high school education.

Together, these two indexes play a much known story between people of color and the areas they are financially and socially forced to reside in. It is clearly unhealthy for the large population of very young children to be living in and another added feature to the EJ Mapper should be the rate of birth defects in the area. Possible birth defects could be directly associated with the lack of regulation or oversight in the environment, and waste management procedures, which could have been caused by the brewery but most likely the highest levels of damage come from the airport, which is directly across from the brewery. It also does not help how busy this area of Newark is, as it is along US 1, which becomes heavily trafficked by cars that omit toxins into the air, harming the depleting ozone layer.

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

For my project, I looked into the history of Anheuser Busch, and its practices at its facilities across the United States. In the video essay, I follow Anheuser Busch’s sustainability advertisement from 1991, into bits of explanation into the ingredients which make beer, as well as an explanation about craft beer culture as explained by Sam Calagione from Dogfish Head Brewery. This deep divide into how consumers seem to shop for beer based on brewery-size and their facility’s involvement with their community and environment, lit a fire under Anheuser Busch to ramp up their effort in the fields of sustainability and humanitarian work.