Newark’s Lead and Water Crisis

by Marzia Choudhury

Site Description:

My project is about the crisis Newark faces as lead has been found in its water supply. Thus, the site my project is located in is the city of Newark, specifically its water system. This includes the water treatment plants that process the water, the pipes which carry the water and the people of Newark who consume this water. The first time news regarding lead in the water in Newark gained traction was during March 2016 after elevated lead levels were found in thirty public schools. Initially, the city government attempted to placate concerns by claiming that the issue was confined to the schools and not indicative of a citywide problem. However, such claims have thus been disproven. My project will also trace the timeline of the issue, the role of different agencies and how the people of Newark have responded to the issue.

What is the timeline of the main events in the Newark lead crisis? How do the demographics of the city impact how the issue has been addressed by government? What actions have the citizens of Newark or local grassroots movement taken in response to the issue?

Final Report:

Introduction

Living in the United States, one’s access to water is often only a couple of steps away, from a quick drink from the tap water in out kitchens or from a nearby water fountain when we are outside. When we take that first sip of water, rarely do questions of where the water came from, its safety and potential side effects, ever come to mind. We usually limit such questions and concerns regarding every day drinking water to developing countries in the third world. Unfortunately, residents living in Newark, NJ are not immune to water problems, despite living in a generally affluent and developed country such as the United States. Despite being the largest city in the state of New Jersey, Newark residents currently face a severe and widespread problem of lead in the water system. They can no longer merely turn on the tap waters in their homes without worry or concern to enjoy a fresh glass of water. Instead, many have to rely on getting and maintaining water filters and allocating extra resources for purchasing water bottles every month. Newark schools have had to shut down many water fountains and many depend on bottled water to fulfill their needs.

This project aims to address multiple questions regarding the lead in Newark’s water. What exactly is the crisis and who are the key players? Who is responsible for the problems with the lead leaching into the water or who should be held responsible? How serious is the issue? What are the health ramifications of lead in the system? How much lead is too much? What role did local activism play?

Plagued by negative publicity from past corruption scandals regarding water funding and mismanagement, Newark city officials first reaction to reports of high lead in the water supply was to dismiss concerns and to deny the severity of the issue. In doing so, they delayed in acknowledging the problem and failed to protect the interests of Newark citizens, exposing them to great health risks and harm. Upon results from lead studies and legal action by the Natural Resources Defense Council and local citizens, the city finally took the first steps to implement solutions, which remain flawed, to resolve this crisis.

The main sources for this project were newspaper articles, published on print and online. For instance, I examined sources from The Star Ledger, The New York Times, and Local Talk Weekly. Because these were accessible to Newark residents, they are an important source of how the lead crisis was being framed and portrayed to citizens. The city government played a large role in this situation, thus this project examined published flyers, brochures and water reports made public by the city. These government documents and public notices showed the perspective of the city government and the goals it wished to achieve. This paper also examined legal documents as part of a lawsuit by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Newark Education Workers (NEW) Caucus filed against the city government. These documents represented the legal activism taken up by environmental advocacy groups and local residents to ensure that all of Newark’s citizens have equal access to safe and clean water.

The paper analyzed the past scandals that the city of Newark faced, regarding mismanagement of funds and corruption in the former water management organization as well as controversy over the potential privatization of the water system. Then the paper demonstrates how the city government’s initial reaction to reports of water troubles was to deny the problem outright and to maintain that the water was safe. Subsequently, the project reveals the reality of the lead contamination based on facts obtained from studies commissioned by the DEP, CDC and the city. The paper also explains legal action and activism by environmental justice organizations against the city government. Finally, the paper concludes with the steps the city has taken to acknowledging and proposing solutions for the lead in water crisis.

Past Scandals of the Newark City Government

Even before the news of the lead contamination was released by the media, the Newark city government had already faced prior incidents which had negatively impacted their image. This impacted how the citizens of the city perceived their government. Thus, it made sense that the mayor’s government did all it could to make sure that the it did not take a negative hit after news of the lead contamination first broke out.

City officials were embroiled in controversy when it was found that the Newark Watershed Conservation and Development Corporation (NWCDC), a city government agency, was faulted for corruption and mismanagement of funds going all the way back to 2008. According to various Star Ledger articles, the NWCDC, a non-profit organization hired by the city government, was responsible for maintaining the running of Newark’s water system and was in charge of supervising the distribution and purification of water to about half a million customers in North Jersey.[1] The organization was dissolved in 2013 after allegations of misappropriation of funds and corruption.[2] In 2014, the State comptroller had released a report which found that the agency effectively stole millions in valuable tax paper money and had made numerous illegal payments.[3] In 2014, a newly formed board of trustees filed for bankruptcy in an effort to regain the funds that were stolen and misused.[4]

A couple of years later after the first speculations and suspicions arose, members of the NWCDC finally did acknowledge their role as conspirators and participants in the bribery scheme. According to a 2016 article published in Local Talk Weekly, Donald Bernard, a “high ranking employee of the NWCDC” admitted to “accepting $956,948 in kickback payments” for his role in giving projects to contractors.[5] Bernard served as a consultant for the non-profit firm from 2008 to. In the case of the NWCDC scandal, the NWCDC was colluding with various contractors to commit crimes of fraud and misappropriation of tax payer money.

The State Comptrollers’ report claimed that poor oversight was the reason why such abuse of public funds occurred from 2008 to 2011 by the NWCDC.[6] Furthermore, the NWCDC’s only customer was the city of Newark, meaning that all of its funding stemmed from taxpayer dollars. Thus, it is shocking that the city’s own non- profit organization that it hired was siphoning away precious tax payer money. Instead of serving the needs of constituents, the NWCDC leadership, enabled by poor oversight and lack of leadership by the Newark city government, was filling their own pockets and serving the needs of those who best suited them, thereby failing to serve the needs of the city’s citizens.

Another major element that comprised the city’s scandals was the controversy surrounding the push to privatize Newark’s public water system. Former mayor Cory Booker first urged the formation of a municipal utility authority in 2010 but was met with harsh criticism from the public.[7] The mayor argued that a private, independent water authority would lessen expenses and make up for deficits in the city budget. However, instituting a municipal utility authority would also require an increase in water rates for the next decade. Furthermore, if the municipal utility authority was not instituted, the mayor claimed that the city budget deficit would have to be fixed by laying off a myriad of “city employees, furloughs and fewer services.”[8] Budget troubles were further compounded when Newark lost more revenue because the state government had decreased aid to the city. Thus, the city government framed the need for the municipal utility authority as a financial and economic necessity for the city.

Opponents of Booker’s proposal argued against privatization of Newark’s water supply for numerous reasons and were successful in making their voices heard and ultimately prevented the establishment of the private water authority. The Newark Water Group, comprised of local Newark residents who were critical of privatizing the city’s water system, was at the forefront of this campaign. Soon thereafter, the group submitted a petition with more than three thousand signatures “asking for an ordinance to make it illegal for the city to enact an MUA…without a public referendum.”[9] In effect, Newark residents demanded to have the right to say how their city- water was going to be run. Joann Sims, Newark resident and member of the Newark Water Group spoke to a reporter during a protest, “Water is a human right. We gotta keep our Newark water public.”[10] A flyer distributed by the Newark Water Group titled “Citizens Alert! Newark Mayor and Council are giving away your water to a Municipal Utility Authority (MUA)”, warned against the institution of a municipal utility authority.[11] The flyer claimed that enabling the formation of the MUA would remove the operations surrounding the city water away “from the direct oversight” of the city government. Furthermore, the institution of the MUA would add another layer of bureaucracy to man the enterprise. This would then lead to setting up contracts for outside companies, unregulated hiring of non-Newark residential staff, increased risk for less oversight and increased possibility of kickbacks. The public merely want their elected officials to do their job, by running an effective government and to not squander tax dollars “to give away [the] water system.”[12] After much activism and protest, Newark citizens were successful in their quest to defeat Booker’s proposal to institute the MUA.[13]

As one can see, the Newark city government has had past scandals in which city-government agencies were mired in corruption and mismanagement of funds. The city also pushed for privatization of the water system, which after much controversy, was prevented primarily by activists comprised of Newark residents. In both instances, Newark residents demanded accountability of the city government for more transparency and honesty. In the first case, the corrupt NWCDC was dissolved only after funds were looted and stolen but in the case of the MUA, the initiative was stopped through citizen action at the proposal stage. Regardless of the outcome, these events garnered negative publicity for the Newark city government. The city administration was portrayed as being out of touch, irresponsible and failing to live up to the standards of integrity and honesty that its citizens deserved. Thus, when news surrounding possible lead contamination in the Newark water supply was coming to light, the government’s knee-jerk reaction was to deny all possibility that citizens were in danger or that the city government had any part to play in the matter. Rather than erring on the side of caution and pre-emptively warning citizens to be careful about water usage and trying to proactively seek out the truth, the city government vehemently denied any role and assured citizens that the water was perfectly safe to drink.

The Water is Perfectly Safe

In March 2016, testing in thirty of Newark’s public high schools revealed dangerous and elevated levels of lead in the drinking water, according to an article published on CNN.[14] The lead levels from the testing showed that from the 30 high schools in Newark had “from 15.6 parts per billion to 558 ppb” in their water system, which higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s “action level of 15ppb.”[15] The schools had then shut down all the water fountains and posted signs in the bathrooms to not drink from the faucets. Bottled water was offered as a means of safe consumption of water. The same article also quoted the Mayor, Ras Baraka: “We are confident to say that the water source in Newark is fine. There are a few issues at the schools….We are dealing with it.”[16] The city government maintained that the source of the water is safe and that the cause of the contaminated lead is “either lead pipes, or household fixtures containing lead or lead solder.”[17] However, another document titled “NPS [Newark Public Schools] Water Quality FAQ,” which answered questions about the March 2016 testing, stated that the exact cause for the lead elevation was not clearly specified.[18] There seemed to be mixed signals regarding the true cause of the high lead levels. After high levels of lead in high schools, the city administration claimed that the lead problem was confined to the high schools and stemmed from pipes, not the water system. However, in another document which was published by the NPS, the exact cause still had not been determined. Even though the city government clearly gave mixed signals regarding the causes of the lead elevations, they maintained the claim that lead problems appeared to be confined to the high schools and not widespread in Newark.

However, after further lead testing showed that there was lead contamination in the water in areas beyond the high schools, the city government released the following statement: “Again, we reiterate that Newark’s water meets all federal and state standards and that this issue is confined to a limited number of homes with lead service lines”.[19] This quotation demonstrates that the city found that the water was safe but that the problem was relegated to the homes with lead service lines, in contrast to what they had originally stated regarding the problem being confined to the tested high schools. Furthermore, the city also claimed that the system which prevents water from corroding pipes, which is one reason why lead had been leeching into the system, had been in place since 1994.[20] The website further stated that the city government sells their water to other municipalities, citing that if the water was truly unsafe, then they would not have been able to sell it to other places in the first place.

As one can see, when news of the lead contamination first came out, the city government insisted that the overall water in the water system is all right and that the problem is confined in the areas where testing revealed the high levels of lead. Furthermore, the city officials also gave mixed signals regarding the exact reason why the lead levels were so high. One source mentioned that it was still to be determined while other sources maintained that high levels of lead was due to lead piping. Regardless of the exact source of lead, the city maintained that that water was still safe to drink, despite knowing that any amount of lead is extremely dangerous to one’s health.

The Reality of Lead and Water Problem

Despite the city’s insistence on the safety of the overall water in Newark and claims that lead was only a problem in confined areas, studies commissioned by the city as well as by the DEP showed that lead levels were extremely high and pose health risks. The main problem of lead contamination stemmed from issues with water treatment.

The city government commissioned a “Lead and Copper Rule Compliance Study” by an agency CDM Smith which was released October 2018.[21] The study stated that the Newark water supply comes from two sources: the Pequannock Water Treatment Plant (West Milford, NJ) and the Wanaque Water Treatment Plant. Both plants use corrosion prevention techniques or “corrosion control inhibitor[s]” to prevent material from leaching into the water.[22] The Pequannock Plant had used corrosion control inhibitors that were based on silicate while the Wanaque Plant had used orthophosphates. However, unlike that of the Wanaque Plant, the corrosion control treatment of the Pequannock Plant had become ineffective.[23] Thus, any water that came from the Pequannock Plant was corrosive and more likely had high lead levels leaching into it.

Furthermore, an article published in The Star Ledger found that the failure of the Pequannock water treatment plant in maintaining proper corrosion control inhibitors occurred in 2012 because the city had “changed the water’s acidity levels…to avoid violating another federal standard” that involved restricting “high levels of possibly carcinogenic chemicals that form when water is disinfected”.[24] Thus, in order to solve one problem, the city had inadvertently caused another. Basically, in order to make sure the water was adequately disinfected, to prevent the accumulation of high levels of cancer causing chemicals, the water treatment at the Pequannock plant was changed, causing the water to become highly acidic. Because of the increase in acidity, the water became more corrosive, making it easier for the water to “eat at the pipes, flaking lead into the supply”.[25] Thus, the city’s corrosion control stopped working because they city had totally changed the chemical composition of the water system. This drastic and dangerous change had caused the treatment of lead to be ineffective.[26]

It is important to note that corrosion control is the sole responsibility of the city.[27] Even though the city initially put the blame on the lead pipes for the high levels of lead, it is the city’s job to put forth measures that would prevent the lead from flaking into or leaching into the water in the first place. Thus, the city’s inability to balance lead treatment with other forms of treatment led the water to be corrosive, leading to increased levels of lead in the water system.

Despite the city’s insistence that the water was safe or that water met federal regulations of lead levels, there is no amount of lead that is considered to be truly safe. [28] Even low levels of lead exposure is “associated with adverse effects, particularly in children”, according to the US Department of Health and Human Service’s toxicological profile for lead.[29] Lead exposure can have a negative impact on “neurological, renal, cardiovascular, hematological, immunological, reproductive and developmental” systems.[30] For instance, exposed children are at risk of decrease in cognitive function such as learning and memory, and in altered “neuromotor and neurosensory function”.[31] Pregnant women who are exposed to high levels of lead can also run a risk of passing on lead to their children through “maternal transfer in utero” and through breastmilk.[32] Thus, all those people who were exposed to high levels of lead in their drinking water because the city failed to properly treat it were at risk of incurring these dangerous health hazards.

Legal Action and Activist Protest

Legal action by the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Newark Education Workers (NEW) Caucus, along with protest by citizen groups played a major role in the city’s shift to acknowledging the severity of the lead issue and taking action to resolve it. The Natural Resources Defense Council, or NRDC, is “an international, non-profit environmental organization” that strives to engage in “research, advocacy, and litigation to protect the public health and reduce the exposure of all communities to toxic substances,” as stated on its website.[33] The NRDC allied with the Newark Education Workers Caucus to file a lawsuit against the city of Newark for violating the Safe Drinking Water Act.[34] According to the lawsuit, the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires officials who are in charge of the water system to test it for harmful materials and to properly treat the water to prevent harmful materials from contaminating the water; “the law also requires states to set and approve certain standards” to ensure that conditions are being met. The lawsuit claimed that the city of Newark has failed to live up to those requirements. Consequently, Newark residents have been exposed and continue to be exposed to dangerous levels of lead.[35]

The lawsuit details further aspects of testing and results that the city of Newark was supposed to do, under order of the NJ Department of Environmental Protection, starting in 2017. Since then and in 2018, more than “10 percent of samples” of water taken during these two periods have tested positive greater than 15 ppb of lead, which is the action level. Furthermore, the lawsuit claims that throughout this entire ordeal, the city has maintained and assured to residents that the water is completely safe to drink and that the problem is only confined to a limited number of homes. Thus, they were clearly downplaying the severity of the issue and trying to shift responsibility from them to other factors.[36]

There has also been activism by Newark residents, who protested the city’s treatment of the water problem. According to an article published in The Star Ledger, titled “Residents send Baraka a message on water woes,” about a dozen protestors gathered outside of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center to demand “clean water”.[37] This protest occurred at the same time current mayor Ras Baraka was delivering the State of the City address. The group of protestors were part of a newly formed “Newark Water Coalition that aims to inform residents about safe water.”[38] The article also featured quotations expressing frustrations from citizens that the city government was not doing their hardest to educate the people of Newark regarding this issue. One protestor stated that “If this was happening to Montclair, in South Orange, in Bergen County” the people there would not stand for this.[39] The cities mentioned by the resident are relatively more affluent than Newark. This suggests that residents are aware that the city could have done more to deliver honest and truthful information regarding the lead problem, instead of trying to downplay the severity of the issue. In addition, residents sense that there may a difference in how this problem is being dealt with compared to that of in more affluent districts where other residents may have more access to power and resources.

After much action by environmental groups such as the NRDC, activism by Newark teacher’s groups and local residential groups, and reports on lead testing, the Newark city government finally acknowledged the lead problem and took action to resolve the issue. According to a flyer distributed to citizens on October 2018, the mayor’s office acknowledged that lead levels were high and that it due to problems with water corrosion treatments.[40] Consequently, the city first instituted a program to “provide drinking water filters” for residents who live in homes which have lead service lines and receive water from the Pequannock water treatment plant. The purpose of the water filters was to reduce lead exposure among residents. The flyer featured a link which citizens can access to see if their home is located in the affected region. Furthermore, the flyer also listed five recreation centers from which residents could obtain water filters. For those who were in the process of obtaining the filters, the city government recommended the usage of bottled water, especially for at risk groups such as pregnant women, infants fed with formula, young children and senior citizens.

The photograph by Sarah Blesener of Newark citizens picking up free water filters at the Paradise Baptist Church shows how Newark residents’ resilience and faith in the city government, as well as in the American dream of prosperity, was tested as they struggled to deal with a seemingly third world problem in a first world country. The photograph accompanied an article published in The New York Times titled “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Hits Newark.”[41] The color blue is the color which is the most apparent. The water filter boxes are the dark blue, the table cloth is a darker shade of blue, almost like a navy blue, the walls of the church has a blue border, the seats behind the pulpit are painted blue, and the poster of Jesus is blue. The color blue represents water obviously, which is most significant because the issue on the minds of the people in the picture is the issue of the lead in the water system. The color blue serves to tie in the theme of water and how people are tense and worried about how to have access to this precious resource in a safe and healthy manner. The color blue can also represent melancholy and sadness and a certain moroseness that the people in the picture are probably feeling. Usually gatherings in places of worship are full of joy, laughter and calmness but the blue motif in the picture suggests the opposite of that. The color blue in this photograph also suggests a sense of seriousness as the people in the picture all have serious expressions and are clearly focused on the boxes of water filters. Thus, the prevalence of the color blue and the seriousness, in addition to its traditional association with water, demonstrates that the water crisis tested the people of Newark and required them to come together as a community, but not for positive reasons.

The contrast of high activity in the foreground compared to the lack of activity in the background suggests that Newark residents had to find strength within themselves, within their own community to deal with the problem and not the city government. The people, both men and women, are standing around the water filters and all seem to wearing the same type of casual clothing, something one would wear when on errands or on the weekend. They see to be around the same age, middle aged adults who are mature and focused on the task at hand. The flurry of activity in the foreground of the photograph serves to starkly contrast with the lack of activity in the background of the photograph: the empty pulpit, the poster on the wall and the American flag standing to one side. This suggests that the leadership, as symbolized by the empty pulpit, was lacking because the picture does not show a leader or organizer to direct the distribution of the water filters. The American flag, symbolizing the country perhaps, is off to one side and is there in name only. The qualities that one associates with the flag, such as freedom, access to resources and prosperity does not match the concerned and tense atmosphere in the photo. The poster of Jesus on the water, symbolizing one of his miracles, seems to beckon to a crowd of people who are not focused on him but rather at the problem at hand. His welcoming gestures, with his arms outstretched, seems to be ignored. This contrast also relates to the environmental justice portion of the project. While the city, in the beginning, denied or tried to downplay the health effects and the reality of the lead in the water, it was the Newark citizens who had to pay the price, quite literally. They were the ones who continued to drink from their tap waters and feed it to their children, both in school and in their homes. Most residents had trusted their city government but probably felt that their trust was broken when the city finally acknowledged the severity of the problem. Thus, the lack of authentic leadership is symbolized by the empty pulpit and American flag standing to the side while the flurry of activity in the front shows the resilience of Newark citizens in the face of this current predicament.

Another strategy the city employed to alleviate the lead crisis was to start the “Lead Service Line Replacement Program”, for which construction began March 2019.[42] The purpose of the program was to eliminate lead service lines which are still in use by the water system. The goal was to substitute about 15000 lead lines with copper. As one can imagine, the duration and cost of this price continues to be extensive. According to the city website, the service lines are pipes that carry the city water to individual homes. Because the service are privately owned by the homeowner, each homeowner will have ti enroll in the program and have pay a maximum fee of $1000 for the replacement of their lead lines. The entire project is expected to be completed in about 8 years.

An Imperfect Solution

Although the city has taken steps to dealing with the lead issue, there still remains problems that prevent the issue from being truly resolved. Though the water filter program is a step in the right direction to curb further lead exposure, it is not a permanent one and is fraught with frustration, on the part of citizens. Different news articles cite resident complaints and concerns regarding the water filter program. For instance, one Newark resident, Gail Brown-Coleman, complained that while her husband was able to obtain the water filter distributed by the city, it failed to fit their kitchen faucet.[43] She added that a person on behalf of the city visited her home later on to give her another filter but “did not provide any further guidance or instructions on how to install [the] filter, did not recommend any alternative filters models…to try, and did not offer to help” to install the filter Brown-Coleman already possessed.[44] Another problem of the water filter program is that it requires maintenance as filters have to be replaced over certain time periods—and the replacement filters cost money. Another resident complained that although the “yellow light began blinking on the filter after a month”, she was not given replacement cartridge by the city. In fact, she has spent “$300 on filter equipment and bottled water for her family”.[45] Clearly, residents still face significant challenges while taking advantage of the city’s attempt at dealing with the lead issue.

When considering the monetary challenges posed by the efforts to gain access to clean and safe water, it is important to consider how the economic demographics of Newark complicates the issue. Although the $1000 cap on the Lead Service Line Replacement Program exists, many residents may still find it difficult to pay that amount. Furthermore, as demonstrated by previous testimonials by residents, the water filter program incurs additional monetary costs, with regard to replacing filter cartridges and paying for bottled water. In an effort to gain access to safe water, Newark residents will be forced to spend their hard earned money on these extra expenses—extra expenses that residents from more affluent areas will not have to face.

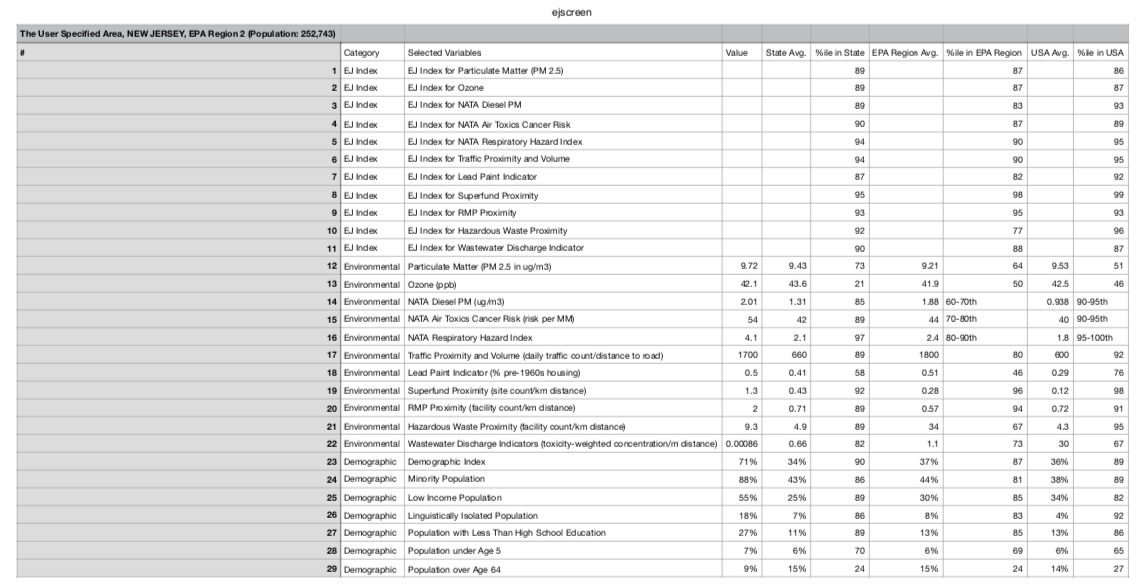

According to the EJScreen data shown above, the city of Newark has a majority minority population (86th percentile in state, 89th percentile in nation), high low income population (89th in state, 82nd in nation), majority linguistically isolated population (86th in state, 92nd in nation), and majority population with less than high school education (89th in state, 86th in nation). “Linguistically isolated” refers to “percent of households in which no one age 14 and over speaks English ‘very well’ or speaks English only (as a fraction of households)”, according to the Glossary of EJScreen Terms. This data shows that the population of Newark is mostly composed of people who are minorities, are at a disadvantage when communicating in English, often lack a high school education and are often part of low income households. This means that citizens are often disadvantaged financially, academically, and probably lack equal access to resources. The percentage of the population who are not able to proficiently communicate in English are also disadvantaged because of the language barrier and how one’s command of English often determines how much one is able to understand what is happening and communicate one’s wants, needs and demands.

These barriers of communication, educational and financial equity may complicate how fellow Newark citizens deal with the lead crisis. Because of economic and financial woes, many Newark residents may find it difficult to set aside extra funds to replace filter cartridges and pay for bottled water. Due to language barriers, residents who are “linguistically isolated” may face additional challenges in getting clear information regarding the lead crisis and its health impact or may feel hesitant to ask questions for further clarification. It is important to note that the city does provide fliers in multiple languages, to cater to the linguistic diversity that exists in Newark. However, flyers and public notices may not be adequate in ensuring that each and every Newark resident at risk of lead exposure is fully aware of the lead crisis and feels confident to ask questions about their individual situation.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, problems with access to safe and clean water is not confined to Newark. According to USA Today Network New Jersey’s analysis of US EPA data, more than one million New Jersey residents receive water from water utilities that have been “cited for excessive contaminants since April 2014.”[46] This issue of water safety is a broader problem of the state of New Jersey.

Despite living in a city whose officials failed to immediately acknowledge the lead problem and proactively take immediate and decisive action, Newark residents refused to be bystanders and let their fate be determined by outside forces. In conjunction with national environmental advocacy groups, the people of Newark, its teachers and local activists, teamed up together to demand that city officials listen to their concerns. Through legal action and local protest, the people of Newark demonstrated that access to clean, safe and affordable water was a right that could not be compromised by any means. They were skeptical of a mayor’s office that only offered blanket statements of assurance and they were not satisfied until they could get to the truth. After much backlash by citizen activists and environmental groups, the mayor’s office finally acknowledged the pervasiveness and severity of the lead crisis and finally started instituting programs to assist the people of Newark. The journey for true and equal access to safe and clean water is not yet over for the people of Newark, but this projects hopes to inspire hope that it can soon be accomplished.

[1] David Giambusso, “Newark Watershed dissolves, leaving city to manage water for 500,000 customers,” The Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), March 26, 2013.

[2] Thomas Moriarty, “Ex-watershed contractor gets 6 months in scheme,” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), Oct. 26, 2016.

[3] Karen Yi, “Former Political consultant for Newark Watershed admits fraud,” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), Jan. 31, 2018.

[4] Thomas Moriarty, “Ex-watershed contractor gets 6 months in scheme,” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), Oct. 26, 2016.

[5] “Former Newark Watershed Conservation Official and Former Contractor Admit Roles in Bribery and Kickback Scheme,” Local Talk Weekly (Newark, NJ), Jan.07-13, 2016.

[6] David Giambusso, “NJ comptroller alleges rampant corruption at Newark watershed, director pleads fifth,” The Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), February 19, 2014.

[7] Meredith Galante, “Hundreds of Newark residents attend Booker municipal authorities hearing,” The Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), July 27, 2010.

[8] Meredith Galante, “Hundreds of Newark residents attend Booker municipal authorities hearing,” The Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), July 27, 2010.

[9] David Giambusso and Akpene Simpri, “Petitions Could Give Control of Newark’s Water to Voters,” The Star Ledger (Newark), August 9, 2012.

[10] David Giambusso and Akpene Simpri, “Petitions Could Give Control of Newark’s Water to Voters,” The Star Ledger (Newark), August 9, 2012.

[11] Citizens Alert! Newark Mayor and Council Are Giving Away Your Water to a Municipal Utility Authority” (Newark: The Newark Water Group, 2009).

[12] “Citizens Alert! Newark Mayor and Council Are Giving Away Your Water to a Municipal Utility Authority” (Newark: The Newark Water Group, 2009).

[13] David Giambusso, “Christie leaves Newark $2M Short,” The Star Ledger (Newark), October 5, 2012.

[14] Dana Ford, “Elevated levels of lead found in water at Newark Schools,” last modified March 9, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/us/newark-schools-lead-levels-water/index.html.

[15] Dana Ford, “Elevated levels of lead found in water at Newark Schools,” last modified March 9, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/us/newark-schools-lead-levels-water/index.html.

[16] Dana Ford, “Elevated levels of lead found in water at Newark Schools,” last modified March 9, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/us/newark-schools-lead-levels-water/index.html.

[17] Dana Ford, “Elevated levels of lead found in water at Newark Schools,” last modified March 9, 2016, https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/us/newark-schools-lead-levels-water/index.html.

[18] “NPS Water Quality FAQ”, Newark Public Schools, accessed May 10. 2019, http://content.nps.k12.nj.us/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/npswaterqualityfaq.pdf

[19] “NEWARK DELIVERS CLEAN WATER AND REBUTS FALSE CLAIMS OF LEAD IN DRINKING WATER.” City of Newark. June 26, 2018. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.newarknj.gov/news/statement-by-andrea-adebowale-newark-director-of-water-and-sewer-utilities.

[20] “NEWARK DELIVERS CLEAN WATER AND REBUTS FALSE CLAIMS OF LEAD IN DRINKING WATER.” City of Newark. June 26, 2018. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.newarknj.gov/news/statement-by-andrea-adebowale-newark-director-of-water-and-sewer-utilities.

[21] CDM Smith, “Lead and Copper Compliance Study,” published October 10, 2018, https://www.politico.com/states/f/?id=00000166-e5f2-dd0d-afe7-eff264510000.

[22] Rebecca Panico, “Study Shows How Newark’s Lead Problem Got So Bad,” Tap Into Newark (Newark), November 9, 2018.

[23] Rebecca Panico, “Study Shows How Newark’s Lead Problem Got So Bad,” Tap Into Newark (Newark), November 9, 2018.

[24] Karen Yi, “What likely caused $75M water problem,” The Star Ledger (Newark), November 21, 2018.

[25] Karen Yi, “What likely caused $75M water problem,” The Star Ledger (Newark), November 21, 2018.

[26] Karen Yi, “What likely caused $75M water problem,” The Star Ledger (Newark), November 21, 2018.

[27] Rebecca Panico, “Study Shows How Newark’s Lead Problem Got So Bad,” Tap Into Newark (Newark), November 9, 2018.

[28] “Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

[29] “Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

[30] “Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

[31] “Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

[32] “Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

[33] Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council Inc, VS City of Newark, “Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief” (Filed June 26, 2018), 6.

[34] Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council Inc, VS City of Newark, “Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief” (Filed June 26, 2018), 1-32.

[35] Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council Inc, VS City of Newark, “Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief” (Filed June 26, 2018), 2.

[36] Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council Inc, VS City of Newark, “Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief” (Filed June 26, 2018), 4.

[37] Karen Yi, “Residents send Baraka a message on water woes,” The Star Ledger (Newark), March 13, 2019.

[38] Karen Yi, “Residents send Baraka a message on water woes,” The Star Ledger (Newark), March 13, 2019.

[39] Karen Yi, “Residents send Baraka a message on water woes,” The Star Ledger (Newark), March 13, 2019.

[40] City of Newark and Newark Water and Sewer, “City of Newark to Provide Drinking Water Filters to Protect Residents Whose Homes Have Lead Service Lines and Lead Plumbing Elements within the Pequannock Service Area” (Public Notice, Newark, 2018).

[41] Liz Leyden, “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Hits Newark,” The New York Times, October 30, 2018.

[42] “Lead Service Line Replacement Program,” Department of Water and Sewer Utilities, accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.newarkleadserviceline.com/replacement.

[43] Rebecca Panico, “Groups Suing Newark Over Lead Claim City’s Filter Program is ‘Haphazard’,” Tap Into Newark, February 22, 2019, https://www.tapinto.net/towns/newark/articles/groups-suing-newark-over-lead-claim-city-s-filter-program-is-haphazard.

[44] Rebecca Panico, “Groups Suing Newark Over Lead Claim City’s Filter Program is ‘Haphazard’,” Tap Into Newark, February 22, 2019, https://www.tapinto.net/towns/newark/articles/groups-suing-newark-over-lead-claim-city-s-filter-program-is-haphazard.

[45] Rebecca Panico, “Groups Suing Newark Over Lead Claim City’s Filter Program is ‘Haphazard’,” Tap Into Newark, February 22, 2019, https://www.tapinto.net/towns/newark/articles/groups-suing-newark-over-lead-claim-city-s-filter-program-is-haphazard.

[46] Russ Zimmer and Andrew Ashford, “Drinking water: 1.5 M in NJ served by utilities that failed tests since Flint,” Asbury Park Press, November 20, 2018, https://www.app.com/story/news/health/2018/11/20/nj-tap-drinking-water-supply-quality-safe/1931148002/.

Bibliography

CDM Smith. “Lead and Copper Compliance Study,” Published October 10, 2018. https://www.politico.com/states/f/?id=00000166-e5f2-dd0d-afe7-eff264510000.

“Citizens Alert! Newark Mayor and Council Are Giving Away Your Water to a Municipal Utility Authority.”(Newark: The Newark Water Group, 2009).

City of Newark and Newark Water and Sewer, “City of Newark to Provide Drinking Water Filters to Protect Residents Whose Homes Have Lead Service Lines and Lead Plumbing Elements within the Pequannock Service Area.” (Public Notice, Newark, 2018).

Ford, Dana. “Elevated levels of lead found in water at Newark Schools.” CNN. Last modified March 9, 2016. https://www.cnn.com/2016/03/09/us/newark-schools-lead-levels-water/index.html.

“Former Newark Watershed Conservation Official and Former Contractor Admit Roles in Bribery and Kickback Scheme.” Local Talk Weekly(Newark, NJ), Jan. 07-13, 2016.

Galante, Meredith. “Hundreds of Newark residents attend Booker municipal authorities hearing.” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), July 27, 2010.

Giambusso, David and Akpene Simpri. “Petitions Could Give Control of Newark’s Water to Voters.” The Star Ledger(Newark), August 9, 2012.

Giambusso, David. “Christie leaves Newark $2M Short.” The Star Ledger(Newark), October 5, 2012.

Giambusso, David. “Newark Watershed dissolves, leaving city to manage water for 500,000 customers.” The Star Ledger (Newark, NJ), March 26, 2013.

Giambusso, David. “NJ comptroller alleges rampant corruption at Newark watershed, director pleads fifth.” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), February 19, 2014.

“Lead Service Line Replacement Program.” Department of Water and Sewer Utilities. Accessed May 1, 2019, https://www.newarkleadserviceline.com/replacement.

Leyden, Liz. “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Hits Newark.” The New York Times,October 30, 2018.

Moriarty, Thomas. “Ex-watershed contractor gets 6 months in scheme.” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), Oct. 26, 2016.

“NEWARK DELIVERS CLEAN WATER AND REBUTS FALSE CLAIMS OF LEAD IN DRINKING WATER.” City of Newark. June 26, 2018. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.newarknj.gov/news/statement-by-andrea-adebowale-newark-director-of-water-and-sewer-utilities.

Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council Inc, VS City of Newark. “Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief.” (Filed June 26, 2018), 6.

“NPS Water Quality FAQ.” Newark Public Schools, Accessed May 10. 2019. http://content.nps.k12.nj.us/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/npswaterqualityfaq.pdf

Panico, Rebecca. “Groups Suing Newark Over Lead Claim City’s Filter Program is ‘Haphazard’.” Tap Into Newark, February 22, 2019. https://www.tapinto.net/towns/newark/articles/groups-suing-newark-over-lead-claim-city-s-filter-program-is-haphazard.

Panico, Rebecca. “Study Shows How Newark’s Lead Problem Got So Bad.”Tap Into Newark(Newark), November 9, 2018.

“Toxicological Profile for Lead,” US Dept of Health and Human Services. Accessed May 1, 2019. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf.

Yi, Karen. “Former Political consultant for Newark Watershed admits fraud.” The Star Ledger(Newark, NJ), Jan. 31, 2018.

Yi, Karen. “Residents send Baraka a message on water woes.” The Star Ledger(Newark), March 13, 2019.

Yi, Karen. “What likely caused $75M water problem.” The Star Ledger(Newark), November 21, 2018.

Zimmer, Russ and Andrew Ashford. “Drinking water: 1.5 M in NJ served by utilities that failed tests since Flint.” Asbury Park Press, November 20, 2018. https://www.app.com/story/news/health/2018/11/20/nj-tap-drinking-water-supply-quality-safe/1931148002/.

Primary Sources:

Source 1: “Important Information About Lead in Your Drinking Water”- Public Booklet Notice Distributed Oct 22, 2018

City of Newark. Important Information About Lead in Your Drinking Water. Newark: City of Newark, 2018. https://www.newarknj.gov/news/city-of-newark-to-provide-filters-to-protect-residents-whose-homes-have-lead-service-lines

This primary source is a copy of the public notice packet (in multiple languages) that the Newark City government distributed to Newark residents regarding the lead found in the public drinking water. The booklet declares that the city will provide water filters in an effort to protect residents who live in homes with lead service lines and lead plumbing elements. The booklet also describes how the water treatment at the Pequannock water service area is no longer effectively remove lead from the water. Thus distributing water filters is the city’s reaction as a solution. The booklet also explains in detail how dangerous lead can be for humans, especially for children under 6 years of age. There is also a specific paragraph, in bold lettering, essentially saying that lead dissolving from water lines is a nationwide problems and that the City does not own the service line pipes (and perhaps is not directly responsible for the lead leaching into the system). I plan to use the booklet to see how the city government is communicating to residents about their role or lack of role in the issue. It is interesting to note that before the distribution of water filters, the City was vehemently denying that the lead problem was severe. The tone and language throughout this notice, however, is anything but urgent and cautionary. Furthermore, this source will be used to see where the blame the City is putting on for the lead crisis and how the language and tone they use reflects that shift in responsibility.

Source 2: Complaint For Injunctive and Declaratory Relief (Legal Document)

Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council, INC., v City of Newark.Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief. June 26, 2018. https://www.nrdc.org/resources/newark-drinking-water-case-documents

This source is a legal document filed by the Newark Education Workers Caucus and Natural Resources Defense Council against the City of Newark on June 26, 2018. This specific type of legal document means that the plaintiffs are asking the court to make an “official declaration of the status of a matter in controversy.” The document presents the lead problem in a stepwise manner, from when lead was first found to be elevated in Newark public high schools to the Mayor’s response in which he assured residents that the lead was not a city wide problem. The document accuses the City of not monitoring lead levels, corrosion control treatments and for encouraging citizens to drink water during this lead crisis. This source will be used to figure out how environmental and grassroots teachers groups have fought back against the city for not doing its job in protecting the interests of the problem, by using the power of the legal system. The specific legal argument will be used in my project to frame the ways in which the city is failing to respond effectively and subsequent court documents will show if the lawsuit will be successful or not.

Source 3: “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Now Hits Newark” by Liz Leyden (NYTimes Article)

Leyden, Liz. “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Now Hits Newark.” The New York Times, October 30, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/30/nyregion/newark-lead-water-pipes.html.

This source is a newspaper article which draws parallels between the lead crisis in Flint to that of in Newark. The main similarity with Flint highlights the role of the city government. Just as in Flint, the Newark City government denied that lead was a problem (despite mounting pressures and evidence to the contrary). As the article describes, the City is still not taking full responsibility for how it handled the issue and maintains that the water is safe. The article cites a wide range of entities, the city, plaintiffs filing a lawsuit against the city and residents of Newark. This source will be used to see how the media is drawing parallels between Flint’s water problem and Newark’s. I will also use the source to evaluate the city’s response and the response of the people to that of the city’s. I will also consider the pictures in the article for my image analysis.

Secondary Sources:

Source 1: Toxicological Profile for Lead

US Dept of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Toxicological Profile for Lead. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2007.https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp13.pdf

This secondary source is a US government document which gives information regarding the chemical properties of lead and its consequent health impact. It is written objectively, with scientific evidence and in language that can be easily understood by laymen and ordinary citizens. This source will be used when explaining the negative side effects of lead, how prevalent it may be in the outside environment and in water and the consequences of lead poisoning on children. This paper will help support the health and medical issues associated with my project.

Source 2: The Aftermath of Flint: Lead Testing in Chicago’s Daycares and Schools

Jager, Maris. “The Aftermath of Flint: Lead Testing in Chicago’s Day Cares and Schools.” Natural Resources & Environment 32, no. 3 (Winter 2018): 22–25. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofm&AN=129650432&site=eds-live.

This secondary source discusses the aftermath of the Flint lead crisis, specifically how states like Illinois, New York and New Jersey are at trying to pass laws and procedures aimed at evaluating water safety and infrastructure. The article also mentions the Safe Water Drinking Act, which I plan to use in conjunction with my primary source which is a legal document. This document will be useful when discussing the Flint crisis, its similarities to that of Newark and the overall importance of improving the aging infrastructure of states all over the United States.

Source 3: “Racial Microbiopolitics: Flint Lead Poisoning, Detroit Water Shut Offs, and The “Matter” of Enfleshment”

Grimmer, Chelsea. “Racial Microbiopolitics: Flint Lead Poisoning, Detroit Water Shut Offs, and The “Matter” of Enfleshment.” The Comparatist41, no. 1 (2017): 19-40. Accessed March 12, 2019. doi:10.1353/com.2017.0002.

Url: https://muse-jhu-edu.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/article/675731/pdf

This source is an article published in a peer reviewed journal which discusses the intersection of racialization/race and the regulation of and access to water, in regards to the Flint crisis. The article also discusses the significance of the increasing privatization of water in the United States. The article also aims to figure out the meaning of water in culture and economics and how the regulation of water inevitably leads to issues of race and culture. This is relevant to my project because this source will add to the social and cultural contexts of why issues relating to water access and health occur in cities like Newark and Flint, primarily composed of people of color and lower income residents.

Image Analysis:

The image chosen for my image analysis assignment is a photograph of Newark residents picking up free water filters at the Paradise Baptist Church during the month of October in 2018. This photograph is a good fit for my environmental justice project because it shows Newark residents grappling with the problem of lead in the water by picking up free water filters to fit over their faucets. The Newark water crisis first came to attention when water fountains in thirty Newark schools tested positive for lead.[1] The parents of Newark children were then notified of the results but reassured that “drinking water alone is not typically associated with elevated blood lead levels”.[2] Furthermore, the city still insisted that Newark’s water was “absolutely safe to drink” and robocalls further spread this message that the lead problem was not an emergency. However, this tone of reassurance changed when the city conducted a study of the water in 2018 and found that because of a change in the Pequannock water treatment plant, lead was and had been leaching into the water of at least “22,000 household taps” since 2017.[3] In addition, the Natural Resources Defense Council or NRDC alongside the Newark Education Workers Caucus, filed a lawsuit against the city government for violating the Safe Drinking Water Act on June 2018.[4] The city has been accused of denying the problem of lead in the water rather than acknowledging it and trying to solve it in a timely manner. While this was going on, many observers started to draw parallels between the water crisis here in Newark and the crisis in Flint, Michigan. Despite initial denials of the severity of the problems, the city finally began to address the issue and started the distribution of free water filters on October 2018.The photograph of Newark citizens picking up free water filters at the church shows how their resilience and faith in the city government, as well as in the American dream of prosperity, is being tested as they struggle to deal with a seemingly third world problem in a first world country.

The photograph was taken by Sarah Blesener for The New York Times article titled “In Echo of Flint, Mich., Water Crisis Hits Newark” written by Liz Leyden on October 30, 2018. This photograph was meant to accompany the article which compares the water crisis of Flint’s to that of Newark. The intended audience was those who read The New York Times and are interested/interested in the Newark water crisis and its parallels to Flint. To find out more about the photographer, Sarah Blesener, I went on her personal website, http://www.sarah-blesener.com. In the section titled images commissioned by New York Times, Blesener, takes photos that center on people. Often times, they are a close up, capturing the intimate, real life moments of a person. The pictures are not staged, but rather taken to capture an intimate and very personal image of the person. The people who often appear are often deep in thought or in emotion, not just with a plastered smile. There is a good mix of people of color and women and they appear to be going about their everyday lives. This is important to note because Blesener’s photograph of the Newark crisis also captures the tension and concern of the people of Newark in a honest and authentic manner.

The main color present and most apparent in this picture is blue. The water filter boxes are the dark blue, the table cloth is a darker shade of blue, almost like a navy blue, the walls of the church has a blue border, the seats behind the pulpit are painted blue, and the poster of Jesus is blue (because he is walking on water, one of his miracles). The color blue represents water most obviously, which is most significant because the issue on the minds of the people in the picture is the issue of the lead in the water system. The color blue serves to tie in the theme of water and how people are tense and worried about how to have access to this precious resource in a safe and healthy manner. The color blue can also represent melancholy and sadness and a certain moroseness that the people in the picture are probably feeling. Usually gatherings in places of worship are full of joy, laughter and calmness but the blue motif in the picture suggests the opposite of that. The color blue in this photograph also suggests a sense of seriousness as the people in the picture all have serious expressions and are clearly focused on the boxes of water filters. Thus, the prevalence of the color blue and the seriousness, in addition to its traditional association with water, demonstrates that the water crisis is testing the people of Newark and is requiring them to come together as a community but not for positive reasons.

The contrast of high activity in the foreground compared to the lack of activity in the background suggests that Newark residents must find strength within themselves, within their own community to deal with the problem and not the city government. The people, both men and women, are standing around the water filters and all seem to wearing the same type of casual clothing, something one would wear when on errands or on the weekend. They see to be around the same age, middle aged adults who are mature and focused on the task at hand. The flurry of activity in the foreground of the photograph serves to starkly contrast with the lack of activity in the background of the photograph: the empty pulpit, the poster on the wall and the American flag standing to one side. This suggests that the leadership, as symbolized by the empty pulpit, is lacking because there is literally no leader or organizer that is there directing the distribution of the water filter. The American flag, symbolizing the country perhaps, is off to one side and is there in name only. The qualities that one associates with the flag, such as freedom, access to resources and prosperity does not match the concerned and tense atmosphere in the photo. The poster of Jesus on the water, symbolizing one of his miracles, seems to beckon to a crowd of people who are not focused on him but rather at the problem at hand. His welcoming gestures, with his arms outstretched, seems to be ignored. This contrast also relates to the environmental justice portion of the project. While the city, in the beginning, denied or tried to downplay the health effects and the reality of the lead in the water, it was the Newark citizens who had to pay the price, quite literally. They were the ones who continued to drink from their tap waters and feed it to their children, both in school and in their homes. Most residents had trusted their city government but probably felt that their trust was broken when the city finally acknowledged the severity of the problem. Thus, the lack of authentic leadership is symbolized by the empty pulpit and American flag standing to the side while the flurry of activity in the front shows the resilience of Newark citizens in the face of this current predicament.

Furthermore, the lack of a leader or one person who could have been be seen in the front of the room in charge of this water filter distribution may also suggest a lack of leadership. The people are who are present in the picture seem to be working together at an equal level, as concerned citizens. However, the emptiness of the front of the room symbolizes the lack of proper and adequate leadership, especially when dealing with the ramifications of the crisis. I think one of the takeaway messages that is presented here is the lack of leadership present visually and metaphorically in this water crisis. The community is there, trying to deal with the problem of the water crisis together but the lack of a person directing this distribution seems to be symbolic of the city’s response to the water crisis. It is in alignment with what actually happened, when the city first denied the lead issue. Only after much pressure by environmental groups and the teachers caucus as well as parallels drawn with Flint and the commissioned study did the city finally acknowledge that the water crisis may be much larger and more severe than originally claimed. This initial denial of the problem is often associated with inefficient and underfunded local governments in third world countries. However, Newark is the largest city in the state of New Jersey, in one of the most prosperous nations in the entire world. Thus, this lack of access to resources as basic as clean and pure water paints a more painful picture for the citizens of Newark in their struggle to gain access to safe water.

As one can see, the specific elements pointed out regarding the photograph helps to support the argument that the people of Newark’s faith in the city government and the promise of the American dream and prosperity is being tested as they encounter a problem that is commonly associated with third world countries which lack equal access to natural resources like water. The setting of the church reinforces the importance of community that the crisis is promoting while the lack of a leadership figure alludes to the lack of adequate leadership and responsibility from the city government. As mentioned in the introduction, this type of problem is not an isolated one as the Flint crisis seems to be a precursor to the Newark crisis. Both cities have a lot in common, such as an ineffective city government, minority and populations of color and lack of expediency in solving the issue. Despite being in the post-war time period and environment, populations like those in Newark and Flint continue to be marginalized and face barriers in regards to equal and safe access to basic resources like water. Overcoming these barriers is often an uphill battle and requires the coalition and cooperation of various local groups in order to force the government to address and take responsibility for the issue.

[1] http://fortune.com/2016/03/10/lead-was-found-in-the-water-of-new-jerseys-biggest-school-system/

[2] http://fortune.com/2016/03/10/lead-was-found-in-the-water-of-new-jerseys-biggest-school-system/

[4] https://www.nrdc.org/experts/sara-imperiale/1400-water-filters-available-newarkers-impacted-lead

Data Analysis:

According to the Newark Community Economic Development Corporation (Newark CEDC) website, the city of Newark is divided further into five wards: North, East, Central, East and West Wards. Furthermore, the North, Central and West Wards are where residents mainly reside while the remaining wards the location of industry (Newark CEDC website). To capture the city of Newark as accurately as possible on the EJScreen map, I chose to use the polygon tool and tried to capture the land which was located within the city boundaries as closely as possible. Because the polygon tool is not as sensitive as I would have liked, I tried my best to exclude areas not within the boundaries and tried not to exclude areas which were within city limits. I drew the boundaries on the EJScreen map in reference with Newark city related websites which showed the authentic boundaries of the city. Because the lead leaching in water crisis is a problem throughout the city, I chose to include the entire city on the map.

According to the environmental tabulated data, the values of each indicator (with one or two exceptions) are all greater than the 50th percentile; in fact, each indicator is in the 80-90th percentile range, if not more (in comparison to state and national data). For example, for indicators of the following: wastewater discharge, proximity to hazardous waste, proximity to superfund sites, proximity to traffic/volume, NATA respiratory hazard index, NATA air toxics cancer risk, and diesel particulate matter, the city of Newark falls into the 80th percentile or greater for each value in comparison to the state and the nation. This means that for each indicator mentioned, there are only 20% of other locations in the state and nation which have even higher amounts of these environmental issues. Thus, this data shows that Newark performs very poorly in terms of the health of the environment and the exposure of its citizens to detrimental environmental factors, as compared to other areas in the state and country.

According to the demographic tabulated data, the city of Newark has a majority minority population (86th percentile in state, 89th percentile in nation), high low income population (89th in state, 82nd in nation), majority linguistically isolated population (86th in state, 92nd in nation), and majority population with less than high school education (89th in state, 86th in nation). “Linguistically isolated” refers to “percent of households in which no one age 14 and over speaks English ‘very well’ or speaks English only (as a fraction of households)” (according to the Glossary of EJScreen Terms). These data show that the population of Newark is mostly composed of people who are minorities, are at a disadvantage with English communication, often lack a high school education and are often part of low income households. This means that citizens are often disadvantaged financially, academically, and probably lack equal access to resources. The percentage of the population who are not able to speak proficiently in English are also disadvantaged because of the language barrier and how one’s command of English often determines how much one is able to understand what is happening and communicate one’s wants/needs/demands. In relation to Sheila and Cole Foster’s book, From the Ground Up, these demographic information seem to be similar to the report given to waste-site companies which describe the types of communities who are the least likely to resist placement of hazardous waste sites in their neighborhoods.

The people of Newark are exposed to more environmental hazards than the majority of people in the state of NJ and the nation and are also part of a group of people who are financially and socioeconomically disadvantaged and more likely to have unequal access to resources. The combination of these two types of data are similar to profiles of other groups who suffer from cases of environmental injustice. Because my research has more to do with the lead in the water system, I probably will not be able to use the specific environmental data. However, I intend on using the demographic data and comparing it with the demographic data in Flint, Michigan.

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

This is a brief video story discussing a specific tv news and newspaper coverage of the elevated lead levels found in Newark public schools, parent reaction to it, and the impact on student health.