Gauley Bridge, WV’s Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster and the Proto-Environmental Justice Poetics of Muriel Rukeyser

by Corey D Clawson

Site Description:

In the years preceding the Great Depression, a project rerouting the New River was developed in order to generate electricity through a planned hydroelectric dam. Construction firm Rinehart & Dennis was tasked with boring a three-mile tunnel through a mountain and employed roughly 3,000 workers starting in 1927 including a large proportion of African American men. When workers encountered a silica deposit on the tunnel’s path, the company forged on with the project and workers, who weren’t provided any protection, contracted the lung disease silicosis and died in large numbers. Muriel Rukeyser, who had previously covered the “Scottsboro Boys” trial and been involved in leftist New Deal politics and film editing, arrived with photographer Nancy Naumberg in 1936 with plans to document the impact of the disaster on the workers as a photo essay and documentary film. Ultimately, Naumberg abandoned the project and Rukeyser developed the work into a series of poems she titled The Book of the Dead. This project will consider how the poet engages with issues of labor and environmental justice, employing her documentarian style to record the consequences of the disaster while highlighting racial and labor injustice. It will also consider the significance of the author’s closeted sexuality in this distant yet intimate approach. Ultimately, this project will offer a greater understanding of how the poet anticipated the environmental justice movement and the significance of artistic engagement in this movement.

“I Get Up to Catch My Breath”:

Race, Queer Love, and Muriel Rukeyser’s Environmental Justice Poetics

Introduction

It is growing worse every day. At night

I get up to catch my breath. If I remained

flat on my back I believe I would die.

It gradually chokes off the air cells in the lungs?

I am trying to say it the best I can.

That is what happens isn’t it?

A choking off in the air cells?

— from “The Disease” by Muriel Rukeyser[i]

These lines from Muriel Rukeyser’s poem The Book of the Dead are based upon the words of George Robinson, an African American man stricken with silicosis who testified about his condition in front of U.S. congressional committee.[ii] In the early 1930s, Robinson was one of thousands of miners who worked on the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel construction project in West Virginia. Like the majority of his fellow miners working for Union Carbide, Robinson would ultimately die of complications stemming from exposure to silica dust, which is why this episode in US history is known as the Hawk’s Nest Disaster.[iii] In his medical testimony illustrating the impact of this exposure—later incorporated by Rukeyser into her poem—he describes how the most mundane act of going to bed at night becomes increasingly impossible because of a looming sense of suffocation.

His testimony offers insight into the degradation of their lives both in terms of their lived experience but also on cellular and cultural levels, which Rukeyser considers in The Book of the Dead. Without being provided respirators or other safety equipment by Union Carbide or its subcontractor, Robinson and his fellow miners breathed in silica dust, essentially microscopic bits of glass that slowly formed scar tissue in the miners’ lungs until they could no longer breathe. Of the 3,000 workers involved in the project, somewhere between 750 and 2,000 died as a result of their exposure to silica and the vast majority (between 2/3 and 3/4) of the workers were African American.[iv] The gradual suffocation of Robinson and his fellow workers by Union Carbide resonates almost ninety years later with the gasps of “I can’t breath.” that have punctuated the last decade of US history as a series of Black and Brown men—including Eric Garner, Derrick Scott, Javier Ambler II, Manuel Ellis, Elijah McClain, William Jennette, Edward Bronstein, and George Floyd—have been pinned down and killed at the hands of police, resulting in hundreds of demonstrations echoing the desperate last words of these men. The loss of George Robinson and his fellow miners is a single episode in a long, violent history illustrating the disposability of Black and Brown men’s lives. [v] The Hawk’s Nest Disaster can be understood as an example of what Rob Nixon calls “Slow Violence” within this history as the trauma inflicted on the bodies of these miners developed over time and out of sight until x-rays were utilized to examine the damage to their lungs. Nixon defines Slow Violence as “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” [vi] Though the violence on display in recent police killings and the silicosis deaths of the 1930s take different forms and temporalities, they highlight a history of structural racism that disregards the value of Black men’s lives.

Muriel Rukeyser was drawn to the Hawk’s Nest Disaster in part because she was interested in this history of anti-Black violence, particularly the racial struggles at center stage in the era. After reporting on the trial of the Scottsboro Nine in the early 1930s (discussed in greater detail later in this paper), she wrote a poem titled “The Trial” in which, according to Christa Buschendorf, “she evokes the historical and economic conditions that influence the trial as well as the inimical atmosphere in which it takes place.”[vii] She also wrote “From Scottsboro to Decatur,” an account of how northern students covering the Scottsboro Nine trial were treated by the local police. Rukeyser had an abiding interest not only in race but also in its enmeshment within US political and economic systems, which she examined from the earliest days of her career—frequently resulting in criticism from her fellow writers.[viii]

This paper will examine The Book of the Dead as a product of the leftist politics informing these political/economic interests in combination with the queer love she experienced as she researched and developed the poem, ultimately arguing that this synthesis resulted in the long poem being a work of proto-environmental justice. Several decades after Rukeyser wrote The Book of the Dead, Robert D. Bullard in the landmark work Dumping in Dixie provided a working definition of environmental justice, the notion that “all Americans have a basic right to live, work, play, go to school, and worship in a clean and healthy environment,” a sentiment reflected in Rukeyser’s examination of the Hawk’s Nest Disaster and the ways that workers and their families were denied their rights to work in a safe, healthy environment.[ix] Rukeyser meditates on these rights as she considers the impact of silicosis on their bodies, their families, and their communities in The Book of the Dead.

Before elaborating the main argument of the paper, I offer context on the poet and the area where the Hawk’s Nest Disaster occurred. The next section of this paper will offer background on the life of Muriel Rukeyser, the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel project, and The Book of the Dead including a brief literature review on these topics. I then begin examining the poet’s leftist politics by examining the social movements she was involved in, her earliest published writings as well as how this early work was received, and why the disaster in West Virginia appealed to her politically and artistically. I will then in turn examine how Rukeyser’s poem began as a collaborative documentary project with another woman. I use the letters between these women, images captured by Rukeyser’s collaborator, and Rukeyser’s hand-drawn map of the area to argue that the early shape of this collaboration is a manifestation of queer love between these women and for those effected by the disaster. The final section of the essay examines The Book of the Dead as a synthesis of her politics and her poetic praxis through a series of close readings from the poem. As she rejects the apolitical conventions of poetry in the era, she adopts a distinctly queer, hybrid approach synthesizing legal and medical testimony, scenes of the local community, and congressional proceedings to tell the story of the disaster while giving voice to the Black men ignored by the national narrative. In order to begin understanding the relationship of The Book of the Dead to Rukeyser’s politics and sexuality, however, we must first consider who she was and what drew her to the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster.

Background & Literature Review

Born in 1919, Muriel Rukeyser was the daughter of Myra Lyons Rukeyser, a bookkeeper, and Lawrence Rukeyser, who worked in the construction industry.[x] The New York household was Jewish and conservative. As William (Bill) Rukeyser, the poet’s son, notes in a 2021 interview, “if people take a look at her literary style or her politics or both and don’t know about her upbringing, it may come as quite a surprise, but her parents were both politically and culturally quite conservative.”[xi] She was educated in the Fieldston schools, which “were associated with Ethical Culture, a quasi-religious movement that attempted to provide a comprehensive philosophy of life without recourse to the supernatural.”[xii] Rukeyser attended college at Vassar and Columbia University. Traces of these early biographical details—Judaism, her education afforded by a well-to-do background—are visible in the poet’s decades’ long career, a career that was incredibly diverse in terms of the forms of writing and topics she addressed as an author. She wrote a musical based on the life of Jewish American escape artist Harry Houdini and she’s written about her faith in essays and poetry, “linking it to ideals of communicative, unified living.”[xiii] Throughout her career, she was deeply engaged not only with literature, but notions of justice, equality (civil rights, feminism, etc.), as well as the more esoteric currents of contemporary philosophy.

In 1929, Muriel Rukeyser’s family, like many, was transformed by the stock market crash that swelled into the Great Depression. Her father’s business and similar “construction business and the real estate business of New York City” were deeply impacted as Bill Rukeyser noted.[xiv] In the wake of the economic collapse, Rukeyser attended Vassar from 1930 to 1932. [xv] The next year, she covered the Scottsboro Nine trial for Student Review. At Vassar, she was also likely involved in launching Con Spirito, a literary journal, with several of her classmates including Elizabeth Bishop and Mary McCarthy to challenge the existing more conservative one.[xvi] As discussed in later sections, her time at Vassar was formative time for her. Leftist and feminist queer social circles as well as her literary pursuits all intersect in this period, with these threads continuing throughout her writing career. Rukeyser’s influence is visible in the work of queer women poets including Adrienne Rich and former student Alice Walker who said, “What I learned from Muriel is that poetry, done well, is always about the truth; that it is subversive; that you can’t shut up and that it stays…. She taught me that it was possible to be passionate about writing and to live in the world on my own terms.”[xvii] Rukeyser would be a target of FBI investigations, speak in favor of civil rights and women’s rights, and voice her opposition to the Vietnam War.[xviii] Only a few years after graduating from Vassar, she was recognized with 1935’s Yale Younger Poets Prize for her first book of poetry, Theory of Flight.

In 1936, Rukeyser, the poet in her early twenties, was drawn to West Virginia to tell the story of the Hawk’s Nest Disaster, ultimately resulting in The Book of the Dead. Rukeyser arrived with photographer and filmmaker Nancy Naumburg, intent on documenting the horrors of what has been called the worst industrial disaster in US history.[xix] They visited the effected communities in the vicinity, conducted interviews, and took photos. Through a collaborative photo-poetry project, the Vassar alumnas hoped to bring to the country’s attention the trauma of gradual suffocation that these workers experienced as well as the disregard of human life by the corporations involved. As I will argue below, this project was a product of leftist politics of the era, but also their creative and romantic partnership. Over the course of her life, Rukeyser had relationships with men and women, but generally avoided being categorized both in terms of sexuality but also her politics, never affiliating as a communist despite three decades of FBI surveillance—perceived as a threat by the institution.[xx] Several of her likely partners collaborated with the poet including photographer Berniece Abbott and Monica McCall— the poet’s partner and literary agent for the last decades of her life.[xxi] Nancy Naumburg, I argue, had a similar relationship with the poet.

The Hawk’s Nest Disaster began in 1930 when the company began drilling a three-mile tunnel through Gauley Mountain between Ansted and Gauley Bridge. Union Carbide’s project was developed to reroute New River through the mountain to generate electricity via new hydroelectric dam. Early in the tunnel excavation, miners encountered a remarkably pure deposit of silica, and as workers drilled through this deposit without respirators or other safety equipment, they breathed in silica dust—microscopic bits of glass that slowly formed scar tissue in the miners’ lungs until they could no longer breathe. Of the 3,000 workers involved in the project (the vast majority African American), somewhere between 750 and 2,000 died as a result of their exposure to silica. A few years after covering the Scottsboro Nine retrial, Rukeyser arrived with Naumburg to write about and expose another injustice affecting a largely Black population of miners whose bodies were treated as disposable. After Naumburg abandoned their collaboration on good terms, Rukeyser completed the project in 1939 and published it as The Book of the Dead, a poem made up of twenty sections, first featured in her second poetry collection titled U.S. 1. It is a hybrid text featuring legal and medical testimony, words of the miners and their families, scenes from the local community, descriptions of the natural landscape surrounding the tunnel disaster, and congressional hearings taking place in the wake of the disaster in order to highlight the mining company’s racial and labor injustices. With this hybrid poetic-documentarian approach, The Book of the Dead’s narrative is one of accountability, demonstrating how Union Carbide consistently minimized the horrors of the disaster and disavowed responsibility as Rukeyser catalogs the consequences of the corporation’s practices.[xxii]

Muriel Rukeyser’s legacy as a poet has been mixed. Throughout her career, she was also derided for her politics, gender, sexuality and appearance. As one critic notes, “She was called a ‘Helen, who was a lesbian,’ ‘a hussy’ who wrote like a ‘deflated’ Whitman, a worn out ‘sibyl,’ and ‘the Common woman of our century, a siren photographed in a sequin bathing suit,’ who was ‘confused about sex.’”[xxiii] Despite these criticisms, Rukeyser’s output was prolific. In addition to eighteen collections of poetry, she also published a handful of children’s books, two plays, a musical, three biographies and a half-dozen volumes of translated poetry. Several additional projects were never published during her lifetime including her novel Savage Coast, which was published posthumously in 2013. In 1948, Rukeyser was in the pantheon of modernist writers with Ezra Pound, nominated alongside him for Yale’s inaugural Bollinger Prize in Poetry. In spite of his fascist politics, Pound was awarded the prize in recognition of The Cantos.[xxiv] This era, following the publication of The Green Wave: Poems is typically framed as the pinnacle of her career, and, as Kennedy Epstein notes, this decline roughly coincides with the birth of her son in 1947. Between 1949 and 1958 the poet published no new volumes of poetry, which is likely a reflection of the demands of single motherhood in the Cold War era particularly hostile to deviations from the nuclear family.[xxv] For the rest of her career she was recognized as a significant poet, arguably relegated to a minor class.

In the decades following her death in 1980, she’s been written about regularly; however, only a handful of book-length studies engaging with her work have been published. Louise Kertesz published The Poetic Vision of Muriel Rukeyser in 1980. It was the first monograph dedicated to Rukeyser, which perhaps imperiled her career having focused on a minor poet.[xxvi] Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead (2003) by Tim Dayton narrows its focus to her poem on the Gauley Bridge Disaster, centering on the formal qualities and arguing that the poem “may be understood through the traditional tripartite analysis of the genres: lyric, epic, and dramatic.”[xxvii] This book-length examination of Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead relies upon a Marxist framework to consider the poet’s relationship to 1930s leftist politics and how it shaped the set of poems. The book provides useful context for understanding the poet’s participation in political movements while making the case for its significance in “the leftist tradition in modern poetry” and its illustration of the “interrelation of horror and hope” in its era.[xxviii] In 2012, Catherine Gander published Muriel Rukeyser and Documentary: The Poetics of Connection, which situates the poet within a discourse of documentary emerging out of the Great Depression with film projects and other documentary media.[xxix] This study pays particular attention to The Book of the Dead. Unfinished Spirit: Muriel Rukeyser’s Twentieth Century (2022) by Rowena Kennedy-Epstein focuses on uncompleted projects of Rukeyser’s. Kennedy-Epstein’s focus on the misogynistic barriers in publishing may also be at play here, potentially illuminating the systemic bias that the poet experienced while using her work to consider social struggles regarding race, class, and labor. The work’s greatest contribution is its explication of Rukeyser’s relegation to this status as minor poet as a result of her leftist politics, her sexuality, and her decision to become a single mother. Kennedy-Epstein is under contract with Bloomsbury to publish the forthcoming biography Mother of Us All: The Life and Writing of Muriel Rukeyser in 2025, which will be the first biography of the poet. In contrast, dozens of monographs have been produced studying the work of Rukeyser’s Vassar classmate, Elizabeth Bishop despite being of the same generation and dying within six months of one another.

In addition to Tim Dayton’s study, several scholars have examined Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead— arguably her most studied work as well as to the Hawk’s Nest disaster. The work of Stacy Alaimo explores how Muriel Rukeyser and Meridel Le Sueur (another 20th century writer with environmental concerns) “construct radically different relations between working-class bodies and the environment,” focusing on Rukeyser’s description of x-rays to reveal the impact of silica exposure upon the miners’ bodies.[xxx] Her discussion of the degradation of the human body via silica exposure is useful to understanding Rukeyser’s treatment and poetic strategies, particularly as they relate to illustrating the corporeal consequences of silica. Alaimo’s discussion elaborates a framework of apathy and unresponsiveness to the disaster within the political and social spheres that could be reframed in terms of systemic environmental racism. Kevin Louis Riel produced a dissertation, “Extending the Poems: Muriel Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead Annotated” in 2018. Drawing upon letters, and the existing body of scholarship, Riel’s dissertation (and companion website housing photos and other artifacts) offers an introduction followed by a detailed analysis of each poem making up the work. Sarah Grieve examines Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead as a work of environmental justice literature, positioning the poet as a secondary witness, “a witness who through careful research and observation bears witness to injustices she does not experience herself.”[xxxi] The article, a revised chapter of Grieve’s dissertation, emphasizes the ways that Rukeyser’s poetic techniques (e.g., homophony, metonymy, repetition, etc.). As secondary witness, Grieves argues Rukeyser is able to examine the personal trauma of the miners and their families while also paying attention to the trauma inflicted upon the land and the non-human animal victims of the disaster. Grieves’s article and her readings of poems in Rukeyser’s collection are useful for understanding some of the strategies the poet uses to portray the trauma of the disaster. In contrast to Grieve, the argument that follows will focus more explicitly on the racial politics of Muriel Rukeyser’s proto-environmental justice poetics.

Also of note is a Martin Cherniak’s The Hawk’s Nest Incident: America’s Worst Industrial Disaster. Cherniak, a physician and public health historian, presents this history of the disaster drawing upon oral history interviews, court documents, and contemporary scientific work detailing new understandings of silica exposure. The historian argues that not only were the corporations involved in constructing the tunnel aware of the dangers posed by this exposure, they indeed went ahead and sacrificed their workers’ lives. This work offers estimates of the impact of these decisions by considering the death toll of the disaster. Because this work is centered on the disaster rather than the poet, it provides some valuable perspective with its focus on the medical and scientific history of the disaster, paying attention to the racial aspects of the disaster. It grounds the project in key understandings of the relationship of Union Carbide with its workers, the corporation’s disregard for worker safety, and the ways that the company as well as the legal system failed these workers. This work offers valuable insights illustrating the systemic racism at play in this incident and its aftermath.

Although The Book of the Dead has been a focal point of Rukeyser scholarship since the turn of the century and some of these studies take into consideration the racial and environmental justice politics of the poet, scholars have not considered this work in the context of the poet’s sexuality. The sections that follow will engage with her radical politics and her queer collaborative projects, considering The Book of the Dead as a synthesis of Rukeyser’s leftist politics and queer love. The next section turns to her writings on the Scottsboro Nine trials to identify the political themes that bridge these writings and her work the Hawk’s Nest disaster. The discussion then turns, in the following section, to Rukeyser’s sexuality. Turning to the letters between Rukeyser and Naumburg and Kennedy-Epstein’s analysis of the poet’s collaboration with photographer Berniece Abbott, I contend that The Book of the Dead was a product of queer love and collaboration. Finally, I offer a reading of Naumburg’s recently recovered photos from this collaboration and selections from Rukeyser’s Gauley Bridge poems to demonstrate how they are an intersection of the writer’s leftist politics and her sexuality.

Radical Politics: Race and Socialism in Muriel Rukeyser’s Early Career

In 1933, Rukeyser traveled to Alabama after graduating from Vassar as part of a group of young adults from the National Student League covering the first Scottsboro Nine retrial in Decatur. The original trials took place in the aftermath of a fight “between a group of white youths and a group of black youths on a freight train traveling through northern Alabama” on March 25, 1931 [xxxii] The black teenagers were rounded up, accused of raping two white women, and—following the deployment of the National Guard by the governor—were put on trial in four trials over eight days and sentenced to death.[xxxiii] The speed of the trials and the flimsiness of the evidence caused a national uproar that resulted in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the United States representing them and a protracted series of legal battles going all the way to the US Supreme Court over the next twenty years.[xxxiv] Rukeyser’s coverage of the trial appearing in Student Review anticipates what she attempts just a few years later with her trip to Gauley Bridge to cover the Hawk’s Nest disaster. There was a particular affinity between the poet’s politics and the tunnel disaster which drew the poet to the site, resulting in her developing The Book of the Dead. These works illustrate a trajectory of the poet’s political project with its focus on issues of race, labor, and capitalism as well as her attempts to shine a light on the injustices taking place at the expense of African Americans.

The writer’s two pieces appearing in Student Review (a National Student League publication), her poem “The Trial” and an essay “From Scottsboro to Decatur,” consider the events of the Scottsboro Nine proceedings.[xxxv] Student Review was a “communist outlet” where Rukeyser served as an editor at the time.[xxxvi] As a result of these leftist political affiliations, the pieces are engaged with racial politics and fit within a historical arc of social revolutions. Published in the April 1933 issue, Rukeyser’s “From Scottsboro to Decatur” offers a prose account of her party’s trip to Decatur, Alabama with the title referencing the venue change from to the smaller town. “We borrowed a car—a car a bit too conspicuous perhaps, and a car with the prime error of having New York license-plates—and left for Decatur,” the story begins, foreshadowing the trouble that awaits the young adults in the deep South.[xxxvii] The first third offers a brief travelogue starting in New York and describing the landscape as well as the marks of racial segregation and injustice as they approach their destination. Just south of Washington, she observes a “railroad station marked in one corner ‘White Entrance’ and in the other ‘Negro’” and in Alabama, she notes “The Negro houses looked like some of the houses in Central Park Hooterville, but they were surrounded by wet fields instead of the rubble of New York City.”[xxxviii] With this comparison, she draws a parallel between the plight of African Americans in the south and NYC’s poor mostly white population currently residing in the Great Depression shanty town. The move suggests a solidarity across racial and geographic lines by suggesting that poverty is a problem experienced by black Americans in the rural South as well as the urban poor.

Upon arriving in the town, Rukeyser and her companions are able to secure press passes to observe the trial but are harassed by the local police and end up in jail. The Call to Action publications for the Conference on Negro Student Problems they distribute to hitchhikers on their way to Decatur are found when they are searched after interacting with William Jones, editor of the Afro American in the courtroom and other African Americans in the town. [xxxix] By crossing the color lines of the South, they agitated the local authorities tasked with maintaining the Jim Crow status quo before being intimidated and run out of town. This is consistent with the coverage of the trial for the New York Times, F. Raymond Daniell covered Rukeyser’s arrest along with two men based upon the literature they carried. However, the poet’s account doesn’t include mention of defense attorney Samuel S. Leibowitz’s threat to quit if Rukeyser and her party remained, declaring “I am solely interested in saving these boys from the electric chair, and I will do my best to see that their case is not endangered by propaganda or agitation from any corner. I have ordered the irresponsible away and they must stay away.”[xl] This coverage illustrates how the group were perceived as agitators. Rukeyser’s actions in Decatur blurred the lines between documentary, art, and activism—something she’d continue to blend with The Book of the Dead and throughout her career.

About nine months after her essay was published in Student Review, her poem “The Trial” was published in its January 1934 issue. The poem is decidedly revolutionary in its tone. Following its peaceful opening stanzas foreshadowing a rebirth and describing the boxcars in the south stalled in their railyards by the Great Depression, the poem situates the Scottboro Nine’s prosecution within a historical arc of Anti-Black violence and revolutionary action most evident in the poem’s climax:

A blinded statue stands before the courthouse,

Bronze and black men lie on the grass, waiting,

The khaki dapper National Guard leans on its bayonets.

But the air is populous beyond our vision:

all the people’s anger finds its vortex here

as the mythic lips of justice open, and speak.

Hammers and sickles are carried in a wave of

strength, fire-tipped,

swinging passionately ninefold to a shore,

Answer the back-thrown Negro face of the lynched,

The flat forehead knitted,

the eyes showing a wild iris, the mouth a welter of blood,

answer the broken shoulder and these twisted arms.

John Brown, Nat Turner, Toussaint stand in this

Courtroom,

Dred Scot wrestles for freedom there in the dark corner,

All our celebrated shambles are repeated here

Sacco and Vanzetti walk to a chair, to the straps

and rivets

and the switch splitting death and Massachusetts’ will.[xli]

Rukeyser’s language and imagery is far from subtle with “The Trial.” This passage encapsulates the poet’s revolutionary racial justice politics with the blindfolded figure of Justice watching over the scene in Decatur. The remainder of the passage is bookended by the specter of state violence. “The khaki dapper National Guard leans on its bayonets” loom around the courthouse as working class “Bronze and Black men lie on the grass waiting.” Conflict simmers under the surface outside of the courthouse. The supporters of the Scottsboro Nine sit peacefully outside of the courthouse as the arm of the state, the National Guard, entrusted with bayonets to maintain racial order through the threat of violence. The poet then gestures towards what isn’t seen: “The air is populous beyond our vision” with the anger of the people, a wave of hammers and sickles, and the ghosts of mythic figures who fought for racial justice. Thick in the air outside the trial venue is the spirit of a people’s revolution—one that answers bayonets with revolution aligned with history.

Rukeyser illustrates an arc of racial justice noting the presence of martyrs and revolutionaries in the courtroom—John Brown, Nat Turner, Dred Scot, and Haitian founding father Toussaint L’Ouverture—standing and fighting in solidarity alongside the Scottsboro Nine. These men fought to overthrow institutions of slavery through rebellion and through legal challenge. The poet articulates with their presence and with mythic imagery is a solidarity against new institutions against anti-Blackness from the unjust prosecution at hand to the lynchings regularly taking place in the southern US. She draws a parallel in this stanza to the final image of state violence, the death sentence of Italian Immigrant anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, and the gruesome hangings of African American lynching victims. She lingers on the image of the lynched man the longest, establishing the stakes of the trial alongside the ongoing violence of the South, the violence succeeding the slavery that Turner and the other fought against and defeated. The image is graphic. The mangled body is described as shattered pieces: a neck strangled and broken by rope forces the face upwards, a mass of blood escapes the mouth perhaps blocking the airway, eyes and brow filled with terror, arms and limbs disfigured by the trauma. This victim is part of the legacy of a broken system that demands justice and revolution. This unjust system robs African Americans of their breath through state and mob violence, as emphasized by her lingering portrait of a lynching, particularly “the mouth a welter of blood.”

In this earlier poem, we see much of the DNA of The Book of the Dead. As Riel notes, the poem “appears in Theory of Flight as part of the longer poem, ‘The Lynchings of Jesus,’” and “prefigures The Book of the Dead’s mixing of left politics, myth, and history.”[xlii] “The Trial” prefigures her work on the Hawk’s Nest Disaster with its concern for history. The poem’s second section, “West Virginia,” reads as an overview of the history from its “first whites” settling the land of the land of the Mohetons to the execution of John Brown following the “brilliant cloudy RAID AT HARPER’S FERRY.”[xliii] In “The Face of the Dam: Vivian Jones,” an “old plantation-house” is juxtaposes new and old forms of slavery as Riel notes.[xliv] The poet maps a history of the state that is built on state violence and worker exploitation. Although The Book of the Dead may not be as direct in its discussion of revolution or as obvious in its imagery, there is a clear resonance between the two projects documenting Black death.

Another key connection between these texts is the focus on breath. Rukeyser’s lynching victim in “The Trial” is grounded in the disfigurement of the body focusing on the terror on the face and the twisted broken body, but also the implicit noose breaking the neck and welling the airway with blood. This image finds corollary in “The Disease” in The Book of the Dead as draws on x-rays and medical testimony, evidence from lawsuits against the Union Carbide mining company and its contractor, to viscerally describe these effects on the lungs of miners affected by the disaster over time:

This is the X-ray picture taken last April.

I would point out to you: these are the ribs;

this is the region of the breastbone;

this is the heart (a white wide shadow filled with blood)….

Between the ribs. These are the collar bones.

Now, this lung’s mottled, beginning, in these areas.

You’d say a snowstorm had struck the fellow’s lungs….

And now, this year—short breathing, solid scars

even over the ribs, thick on both sides.

Blood vessels shut. Model conglomeration.[xlv]

The clinical tone is nearly the opposite of the jarring and revolutionary tone of “The Trial.” The violence described here is internal and gradual. The doctor orients the reader/juror to the geography of the cardiopulmonary system before pointing out the silica dust nodules forming and getting worse over time as the lungs gradually scar and suffocate the miners over time.

With these disparate approaches, Rukeyser continues her political project advocating for Black lives, but illustrates the violence playing out on two different scales. Rob Nixon theorizes these disparate forms of violence as slow—violence “that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all”—and spectacular—violence that is more immediate and cinematic.[xlvi] Across this early work by Rukeyser, we see her paying attention to the immediate as well as the historical dimensions of anti-Black violence. Her writings on the Scottsboro Nine relies on the immediacy and visibility of the trial while The Book of the Dead (though it discusses another event on the national stage) focuses more on the invisible and gradual nature of the violence against the miners at Gauley Bridge. These works by Rukeyser share formal features in their deployment of myth and history, doing so to bring attention to the systemic failures of US legal and economic systems for African Americans and for the working class. While her leftist politics may have drawn her to the disaster as they did in the case of the Scottsboro Nine proceedings, her intense relationship with Nancy Naumburg informed her approach to the incident in The Book of the Dead, an approach I will later frame in terms of queer love.

Queer Love & Art: The Peril and Potential of Collaboration

The relationship between Rukeyser and Naumburg is nebulous in many respects. Because their collaboration was so early in Rukeyser’s career, relatively little has been preserved. The working notes and drafts of The Book of the Dead weren’t filed away and preserved like her later work.[xlvii] This reflects the fact that she was still establishing herself as a poet and in the somewhat whirlwind lifestyle Rukeyser led as she was leaving college. Her trips to Alabama, Gauley Bridge, and to Europe to cover the Spanish Civil War in young adulthood suggest a roaming lifestyle perhaps driven by what Manolo Guzmán’s notion of the sexile, “the exile of those who have had to leave their nations of origin on account of their sexual orientation.”[xlviii] As Hicok has noted, the Rukeyser was part of a generation of queer poets at Vassar College, a women’s only institution of the era.[xlix] Given her conservative upbringing, it would be unsurprising if she experienced a sexual awakening in college and embraced her sexuality while exploring new places both domestically and internationally like several poets of her generation including Vassar classmate Elizabeth Bishop who relocated to Key West Florida and later Brazil for roughly two decades of her life.

The physical evidence of the relationship between Naumburg that has survived and has been preserved in the archives is not only scant but also one-sided. Aside from the artifacts that have resurfaced in recent years—Naumburg’s photos and Rukeyser’s doodle—the traces of their relationship are restricted to a half dozen folders housed in New York Public Library’s Berg Collection. The contents of these folders are almost all the letters of Naumburg to her friend and collaborator—letters mostly written in the years before their trip to Gauley Bridge and after the publication of US-1. Rukeyser’s half of the conversation is lost perhaps misplaced or perhaps burned and destroyed. However, a handful of sheets by Rukeyser do survive in these folders, the letters written to Naumburg that were revealingly never sent. The surviving letters suggest that the two Vassar women were in a relationship, and that The Book of the Dead is a product of queer love in parallel with a later collaboration between Rukeyser and Berniece Abbott.

Naumburg’s extant letters illustrate a similar roving nature to Rukeyser’s trajectory, occasionally managing to meet in person. The bulk of this correspondence is dated between April 18, 1932 through August 24, 1935, in the years before their trip to Gauley Bridge, and sits in the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection, though some additional correspondence exists in the Library of Congress collections in Washington, D. C. Naumburg’s own artistic pursuits as a documentarian took her to diverse locations for months at a time. For instance, she devotes a significant amount of space in their correspondence explaining why work shooting a documentary on fishing boats in Nova Scotia is taking longer than expected.[l] (Naumburg’s letters are undated, so dates included are based upon postmarked letters included in the same folders as available).

Overall, Naumburg’s correspondence reflects some hesitancy on Naumburg’s part, which dissipates. One of her earliest letters advises Rukeyser to distance herself and defines their relationship as a friendship.

You are altogether too fine and too firmly woven to have anything to do with a stupid, selfish brute who has no feeling for other people. You must transfer your feelings. There are new associations to be built up. Just at present I feel that I want to be completely free from all personal relationships of any sort.

If you want to see me in the future, please let it be free from this thing which is always between us, which makes me draw apart from you.

You must know that I value you as a person so that would be a great loss not to see you.

Nancy[li]

The advice for Rukeyser to transfer her feelings suggests a non-reciprocal admiration in light of the expressions of admiration as a person whose presence is valued by Naumburg. However, despite her calls to eliminate “this thing which is always between us,” she does not rule out the possibility of a romantic relationship entirely. She characterizes herself as a brute seeking to be “completely free from all personal relationships of any sort.” The possibility is ruled out for this reason and not on the basis of gender or sexuality. She attributes this distancing to a desire not to have personal connections in the moment.

Later letters indicate that their relationship deepened into friendship and perhaps romance. They kept in touch regarding one another’s projects writing to one another regularly to coordinate phone calls and visits when they were able to find themselves in the same city for a moment whether that be Provincetown or New York. “I wish to God I could come—but I don’t see how I can,” she notes longingly from Nova Scotia after some time apart.[lii] When visiting her parents’ farm in Deal, New Jersey, Naumburg longs to share her life with Rukeyser, writing “On the train, one can see the farm where we lived. The land seems so small now. It was large enough to get lost in then. I’d like you to see it all.”[liii] There are also signs of spats between the two as they struggle with being apart for extended periods of time. Following one disagreement, Nancy apologizes: “I don’t quite know why yesterday was so unpleasant — so like being up a brick wall. But it was. And I’m sorry. If you could meet me tomorrow evening after nine—phone me in the morning, early.”[liv] In another, she attributes their disagreements to Rukeyser resenting her going away before admitting “that made me angry…. We have known each other so well that we can take liberties in wounding each other. That is much truer of me than of you. You are so fine that you won’t spit back. The last thing I want to do is stop seeing you. You are part of my life. Will you wait a few days until I have gotten over this inexcusable childishness?”[lv] Naumburg’s assertion that “You are part of my life” reads as a genuine declaration of love. Despite their feelings hurting one another, she frames her desire to remain part of Rukeyser’s life a constant.

An undated letter from Deal, NJ reads as a turning point in their relationship— one in which Rukeyser’s art and sexuality makes sense to Naumburg for the first time. The filmmaker notes two points of growth in her relationship with Rukeyser, the first being a growing appreciation for Rukeyser’s poetry requesting a copy of her first book before a trip. The second is a growing appreciation of the poet’s “sense of values.” “I am beginning to accept them not as your values but as values which although they do not solve all known problems, seem nevertheless to afford as any other pragmatic theory.” There is an ambiguity to the conversation. Naumburg is clearly experiencing an awakening of some sort that could be political or sexual or some combination of the two. Framing the opening world view in terms of values could refer to either. And when she refers to “solving all known problems,” she could mean social problems or the problems of the relationship between the two women as she accepts Rukeyser’s advances. Either way, she sees these values making a person she deeply admires and respects, closing the letter “One of the causes for my sympathy to [these values] is what they have given you—an openness and generosity and understanding which is very rare. Let me again thank you for the beautiful evening. My love to you, Nancy.”[lvi] Naumburg suggests that she sees something special in Rukeyser that she would like to emulate. Such a declaration likely deepened their relationship and reflects a turning point between Naumburg’s initial desire to be free of attachments and her insistence that despite Rukeyser’s jealousies or resentments that the two belonged in one another’s lives.

The correspondence from Rukeyser that survives even more strongly suggests a romantic relationship, despite only a handful of unsent letters, postcards, and ephemera surviving. Written on the back of a ticket to a 1935 performance of W.H. Auden’s musical comedy The Dance of Death by The Experimental Theatre at Vassar College is a bidding note to Naumburg: “Water is laid on water, night on night, day on day, and the place is lovelier and more bateful.[lvii] But my house is so beautiful and the sea underneath. — Will you wire? Will you come?” One of the undated letters requests a letter from Naumburg after some time, “For all I know, you are dead or in California…I want to hear from you, very much. I have always had an idea that if I saw you or heard from you poems would leak out of my fingers. Just now, they don’t.”[lviii] These words mirror the emphasis in Naumburg’s letters with staying in touch and meeting. Rukeyser’s creative production is rooted in her connection with her partner, but the creative flow has dissipated after not having had communication in roughly a week. As Riel notes, Rukeyser’s relationship with Naumburg was so strong that the poet named one of her executors in three wills written between 1934 and 1937 including one that declares the photographer entitled to fifty percent of the profits from her first book in the event of the poet’s death.[lix] One final letter seems to most explicitly frame their relationship as romantic also points to the end of that relationship:

Don’t delude yourself that you miss me, because this time you walk back up the street still in the city while other people go, and because old supports seem sharply cut away. I’ve asked you desperately for help, when doing that was degrading for me, and you’ve gone away and stayed silent; I’ve been rather a seismograph to your moods at times when it shook me appallingly to do that, and you’ve always said ‘I never needed you; I want to go away, to be alone; I never wanted you to love me.’ So don’t.[lx]

Because this letter is unsent and undated, almost nothing is certain about this letter and the circumstances under which it was written. It seems to reference the initial aloofness of Naumburg’s letters and Rukeyser’s resentments at her being away referenced in other letters. It seems likely that this letter encapsulates the reasons for the two distancing from one another following the abandonment of their collaboration on what would become The Book of the Dead. It also seems likely that this letter is the strongest evidence that they were in love. This correspondence suggests that the relationship between the Vassar graduates in the years before their trip to Gauley Bridge to document the Hawk’s Nest Disaster was deep and romantic. It also suggests that The Book of the Dead was a product of not only their queer love—one that Rukeyser framed as fuel for her creative work.

Kennedy-Epstein’s Unfinished Spirit chronicles a similar collaboration taking place roughly two decades later bearing several parallels to the Naumburg-Rukeyser collaboration. In the 1940s, Rukeyser partnered with photographer Berniece Abbott, developing a book project titled So Easy to See. First, these projects bear resemblance in that neither were completed with only fragments of the collaboration surviving—pieces of drafts exist while no final assembled versions do. Second, the final product of this collaboration was to be an amalgamation of words and images. Abbott had recently developed the Super-Sight Camera that enabled her to take magnified images while eliminating the graininess of earlier techniques. The poet composed text to accompany Abbott’s photographs of a halved apple, Rukeyser’s hand and eye, walnut, bug, roots, and soap bubbles.[lxi] Clearly, the poet was interested in the potential of this combination of words and images. As she suggests decades later in her collection of essays The Life of Poetry, she understood the collaborative components of words and images as producing an array of simultaneous meanings: “in this combination…there are separables: the meaning of the image, the meaning of the words, and a third, the meaning of the two in combination. The words are note used to describe the picture but to extend the meaning.”[lxii] With both of these collaborative projects, Rukeyser sought to queer disciplinary and artistic boundaries. In the case of So Easy to See, a project bringing together philosophy, media theory, and science to examine ways of seeing as reflected in the project’s alternative title Certain Ways of Seeing, Things, Seeing Things. With The Book of the Dead, the women hoped to push the boundaries of art and politics. As Kennedy-Epstein suggests in Unfinished Spirit, women artists “Collaborating… becomes a particularly complex feminist project about recovery, legacies, counter-canons, and pedagogy.”[lxiii] Naumburg’s collaboration with Rukeyser can be understood as an intervention into the politics of the era, recuperating the voices of the silicosis afflicted miners, but also an intervention into what poetry can do and teach by infusing their documentary photography with radical politics as well as legal and medical discourses. As discussed earlier, Rukeyser framed their relationship as creative fuel.

As reviews of U.S. 1 and the rejections of So Easy to See suggest, these hybridization approaches were not well received by the literary establishment.[lxiv] “Muriel Rukeyser has not yet entirely clarified her expression,” writes Benét, William Rose, critiquing U.S. 1 as muddled.[lxv] Willard Maas declares that the volume ultimately “will become an increasing source of embarrassment to her. One admires Miss Rukeyser’s inventiveness in the first section, Book of the Dead; and one admires also her intentions which are ambitious to the point of audacity.”[lxvi] The poet’s critics, from an earlier generation, take on a paternalistic tone when discussing the young woman poet’s work. These critics acknowledge the innovation at the heart of The Book of the Dead bringing together a critique of capitalism with poetic and legal/scientific discourses such as the testimony concerning the x-ray. So Easy to See languished in publication limbo for years as publishers saw little value in the experimental text written at a crossroads of marginalizations as “radicals, dissidents, women, lesbians” producing art at the onset of the Cold War.[lxvii] This misogynistic criticism, as Kennedy-Epstein notes, extended to her unauthorized, similarly “discipline-defying” biography of physicist William Gibbs, with reviewer Philip Blair Rice suggesting that the book’s approach “proved [Miss Rukeyser] a hussy and the book no good.”[lxviii] The poet’s purity as a women is tied up with her purity as a writer in the reviewer’s eyes. Rob Nixon notes that similar misogynistic dismissal met the work of Wangari Maathai and Rachel Carson describing slow violence, reflecting the “insidious dynamics and repercussions of slow violence concealed from view.”[lxix] By transgressing traditional boundaries of genre infusing philosophy, poetic language, and the facts of Gibbs life, she goes too far in the reviewer’s eyes who conceives the adulteration of the biographical form as unsuccessful but also overly transgressive.

Finally, Kennedy-Epstein has similarly characterized the collaboration between Rukeyser and Epstein as a union “probably as lovers and then as collaborators.”[lxx] The above-discussed letters between Naumburg and Rukeyser suggest a similarly layered relationship. Naumburg and Rukeyser’s correspondence suggests that they valued each other as artists discussing each other’s writing and documentary projects in the years following their attempted collaboration in Gauley Bridge. It also suggests that they experienced a form of love existed prior to their communication implying their relationship breaking apart and their apparent incompatibility. Kennedy-Epstein also draws this parallel between the Naumburg-Rukeyser and Abbott-Rukeyser collaborations as a collaboration with another female photographer; however, she does not suggest in Unfinished Spirit that the poet’s relationship with Naumburg was romantic.[lxxi] Their correspondence suggests that the power of their relationship would produce a powerful piece of art that neither could produce alone by harnessing the meaning of Rukeyser’s words, the meaning of Naumburg’s images, and, to quote Rukeyser, “a third, the meaning of the two in combination” produced through their romantic and artistic relationship.[lxxii] Through their combined efforts, they hoped to expose the injustices of the Gauley Bridge disaster.[lxxiii] The next section considers how The Book of the Dead can be understood as a product of this unrealized collaborative vision and Rukeyser’s radical politics. By examining images from their collaboration, we gain an understanding of how Naumburg and Rukeyser intended to express their radical politics while shedding a light on the slow violence of capitalism.

The Book of the Dead as an Act of Queer Love and Political Poetry

Quickly flipping through Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead, it is easy to see how it is set apart from other poetry. Perhaps the most striking feature on such a cursory glance is the inclusion of a table. What sort of poem includes a table? Kertesz notes that although writers like John Dos Passos adopted documentary techniques with “its inclusion of newspaper headlines and ‘biographies’ of outstanding figures” Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead was unquestionably original in its mosaic format, declaring “No poet had used prose documents in this way before.” [lxxiv] This format stitches together medical testimony, interviews with survivors, congressional proceedings, portraits of landscapes interrupted by the dam’s industrial development, histories of West Virginia, and this table—a New York Stock Exchange listing.[lxxv] Rukeyser chose the mosaic, documentarian form of The Book of the Dead to illustrate the racial and labor injustices, to elevate the perspective of the Black men who were erased from the narrative, and to express a political and poetic vision of humanity based in queer love and leftist politics through the development of new hybrid/queer forms. The poem also draws upon a diverse array of voices including reporters, doctors, engineers, social workers, and of course the miners and their family members. This final section first visually analyzes the remnants of Rukeyser’s collaboration with Naumburg and then turns to sections of The Book of the Dead to examine how slow violence is represented in the unfinished and published works as hybrid texts emphasizing the indifference of capitalism and the absence of these Black men from their communities.

In 2018, a new edition of The Book of the Dead was issued by West Virginia University Press following many years out of print and features recently recovered images related to the conception of Rukeyser’s poem. This edition included an introductory essay by Catherine Venable Moore and a list of miners who died of complications stemming from their exposure to silica in the mine. With her introductory essay, Moore shares a set of unearthed archival images including three of Nancy Naumburg’s photographs from her time collaborating on the project with Rukeyser in 1936. Also reproduced in this edition is a hand drawn map of the area drawn by the poet. Together, these images provide insight into the collaboration that Rukeyser and Naumburg had initially envisioned before The Book of the Dead took shape. Their images center on the communities impacted by the Union Carbide’s tunnel disaster and gestures toward the losses within those communities and, to a lesser extent, its impact on the natural world.[lxxvi]

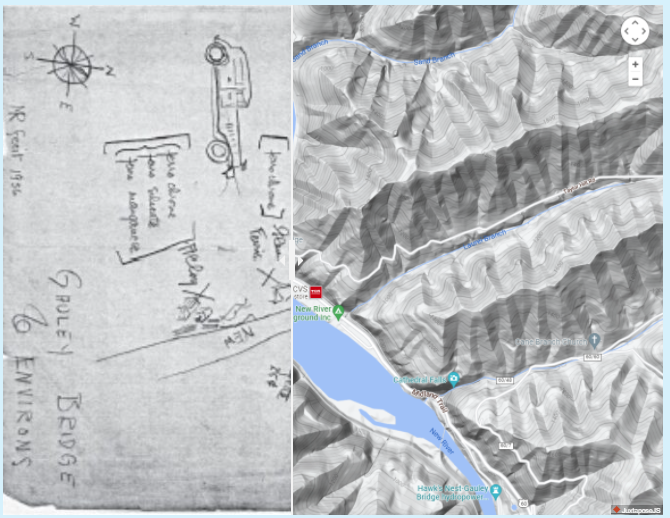

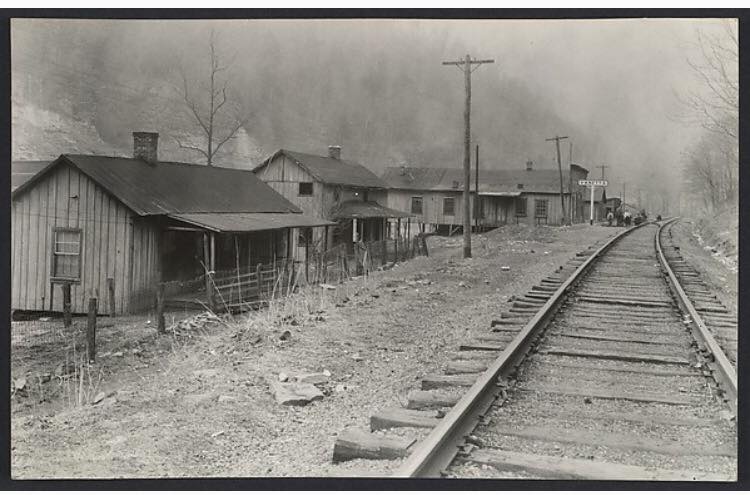

Fig. 1: “Gauley Bridge & Environs,” paper map by Muriel Rukeyser, 1936, Library of Congress[lxxvii]

Rukeyser’s map bears the title “Gauley Bridge & Environs” and is dated 1936 followed by the poet’s initials, perhaps indicating her identification as an artist or at least the significance of the work documenting the horrors of the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster. Moore located the map among a collection of the poet’s papers held by the Library of Congress and her introductory essay uses the map to explore the area 80 years later. The decades-old map shows its age in this reproduction which captures the original’s disintegration along its crease and edges. This fold potentially indicates that the map was likely tucked away as part of the poet’s process—her notes on the project—and not intended for display. Although no clues as to the circumstances of its production seem to have survived, one could imagine the two women sitting down over lunch, sketching out the terrain, and discussing their collaboration.

A drawing of their car on the left-hand side, possibly a 1929 Packard sedan, stands out on the map in terms of detail and scale and performs the function of placing them as outsiders in this rural community conscious of their status as outsiders. As outsiders, it is understandable that Rukeyser’s drawing doesn’t map perfectly onto the landscape as captured by 21st century satellite imaging. The map isn’t to scale and certain elements of the map don’t align: the names of the New and Kanawha rivers seem to be swapped and Rukeyser’s cardinal directions seem off by about ninety degrees. Click on the image below to view a slider to compare Rukeyser’s map and a modern-day map of the area. At the very least, the 1936 map is a window into the artistic and documentary project offering clues into what Rukeyser (and perhaps Naumburg as well) considered the landmarks of this terrain and the boundaries of their investigation, which stop at the page’s edge.

Fig. 2: Slider image of Rukeyser’s map imposed on a Google Map of the same area. Click to interact.[lxxviii]

The tunnel, the main site of the industrial disaster, is tucked away in the top right corner of the map, leaving the communities and the natural landscape at the center of this sketch. On the opposite side of these communities sits a tiny factory spewing out smoke labeled “Alloy,” suggesting that Rukeyser has observed that these towns are surrounded or dominated by industry and impacted by the consequences of their toxins and labor practices. In the middle of the map sits an intersection of three rivers New River, Kanawha River, and the Gauley River. Clearly the tunnel is a key part of this investigation as the source of the toxins slowly killing the miners. It is labeled with a distance of “3 ½ miles” as well as markers indicating the dams infrastructure set up on the water’s route (likely compressed to fit on the page); however, it makes up only a small stretch of the map in comparison to the expanses of the natural and human worlds occupying the rest of the area. The banks of the rivers are lined with cartoonish trees, but also various landmarks from the area: towns like Vanetta and Gamoca, the home of Mrs. Jones, a country road weaving back and forth across a creek flowing into the Gauley River.

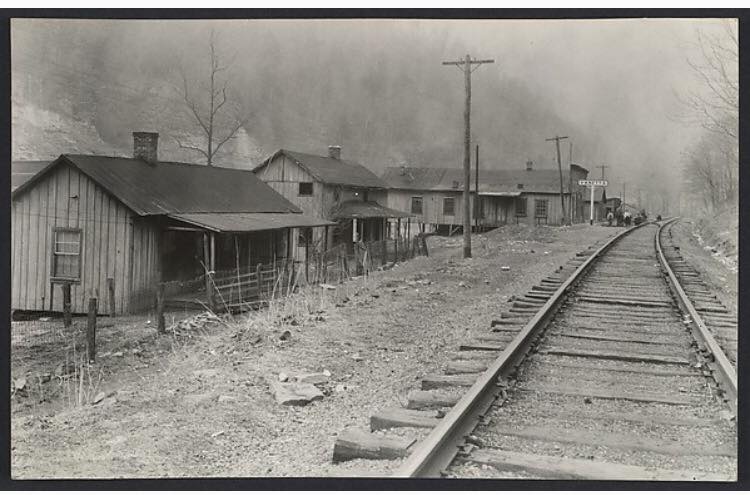

These landmarks correspond to those featured in Rukeyser’s poetry and Naumburg’s photos. Two of Naumburg’s photos are identified as scenes from Vanetta (a shot of the town adjacent to the railroad tracks, and the kitchen of George Robinson, one of the miners whose testimony is featured in the poem), and as Moore notes, Mrs. Jones is introduced in “Praise of the Committee” and identified as having “three lost sons, husband sick.”[lxxix] The locations on this map presage the mosaic of perspectives and testimonies that would become The Book of the Dead: scenes from the tunnel disaster, the destruction of families and communities, toxic industry ambivalent to workers’ health and safety.

Fig. 3: Hawk’s Nest Dam, 1936, Nancy Naumburg[lxxx]

Naumburg’s photos also illustrate these aspects of the disaster. In her photos, we are offered a more direct window into what she found visually interesting and representative of the story she hoped to tell with Rukeyser. Though it’s very possible more photos were taken in the area, we are left only with these three images to assess the project that might have materialized (two of three of which resurfaced in the last decade in the form of glass plate negatives found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection). These images are the Vanetta photos of George Robinson’s kitchen and the community as well as a photo of the dam. The spaces represented are district and significant pieces of the story, representing disruptions at three distinct levels: the natural world, the local community, and the home. Assuming these surviving images are representative of how Naumburg conceived the project, she seems to have been intent on capturing on film the stillness and emptiness resulting from the tunnel project rerouting water towards the hydroelectric dam. Her photograph of this dam is serene. Despite the motion of the water as it cascades down, there is a stillness to the image. The dam at the center, captured at a side angle, is an imposing structure spanning the width of the photo. Foliage covered hills peek out from behind the dam, gesturing to the project’s effects on the natural landscape. It contains the water but also obstructs and destroys nature.

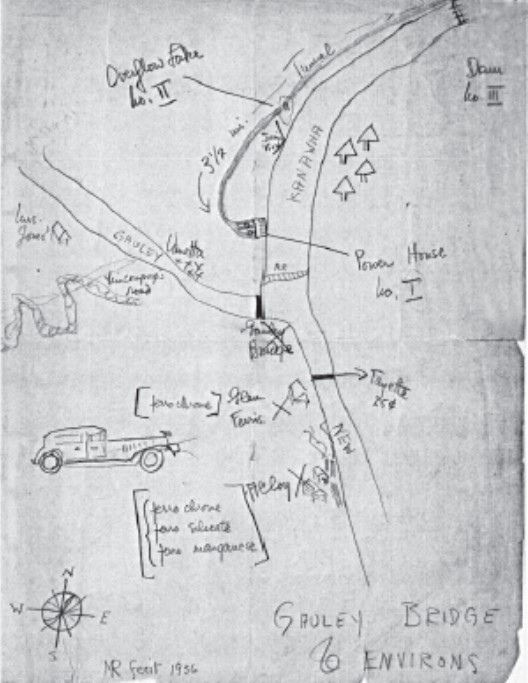

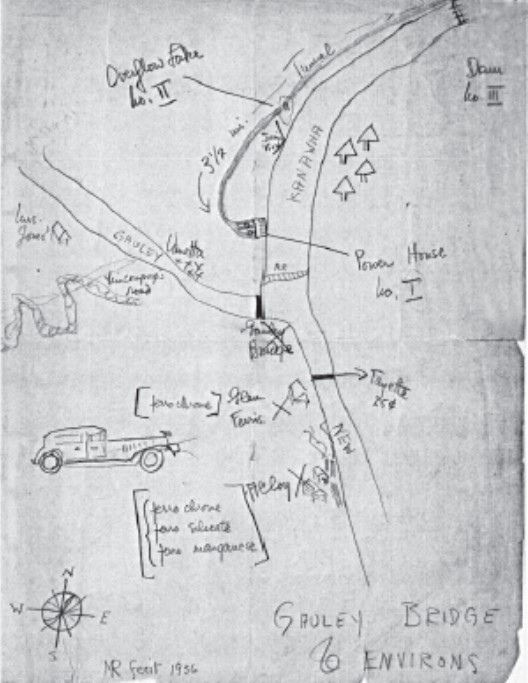

Fig. 4: Shacks and Railroad Tracks in Vanetta, 1936, Nancy Naumburg[lxxxi]

Her photograph of Vanetta functions similarly but suggests a more human impact of the project. Railroad tracks, a sign of industry on the landscape, cut through the bottom right quarter of the image. The wood panel houses to the left of the track appear weathered and modest. Absent from the image are any residents of the town, which seems to gesture toward the loss of the residents who had already started dying painful deaths and the looking deaths of many more, suffering from and expecting to die of silicosis. The third photo zooms in more on this sense of looming loss as it focuses on a single home. A stove sits on the corner with various pans and cooking tools hanging on the wall of George Robinson, one of the African American miners diagnosed with silicosis. Such a photo offers insight into his family’s socioeconomic status but also invites its audience to consider the haunting absence of life in the photo– the meals not cooked, the conversations unspoken, etc. With each image, the alienating stillness and emptiness caused by the tunnel project accretes and its impact on nature and community becomes more apparent.

Fig. 5: George Robinson’s Kitchen in Vanetta, 1936, Nancy Naumburg[lxxxii]

Aside from the archived correspondence, these photos and Rukeyser’s map are perhaps the most illuminating clues available to recover the collaboration between these two women because, as Moore notes, Rukeyser’s research notes did not survive.[lxxxiii] Through these images, we gain an understanding of how both women understood the tragic story they intended to convey and the strategies they developed for illuminating the impacts of Union Carbide’s actions on its workers, local communities, and the natural landscape. Rukeyser’s map frames the area where the tragedy took place—the site of the industrial disaster, the local towns, and even individuals affected by the company’s actions—and can be understood as a visual draft of the collage of perspectives she would synthesize in writing The Book of the Dead.

Though Naumburg’s photos didn’t become part of the documentary project that these women began collaborating on, the images do offer insight into the women’s efforts to capture the disaster’s effects on people, community, and environment, but also signal a potential trace of Naumburg’s influence on Rukeyser’s poem. Naumburg’s attention to these locations and levels of devastation with the kitchen (family level), Vanetta (community level), and the dam (ecological/capitalistic levels). As Rukeyser explores the vast implications of capitalism on these environs in her poem, she accounts for these levels in its mosaic approach with its testimony from miners such as George Robinson and their family members, its descriptions of dam’s impact on the natural landscape, its accounts of the atrocities whispered within the community and also its descriptions of the biological impact of silica on the lungs of Union Carbide’s workers. In this context Rukeyser’s map of the area also becomes a map for understanding the strategies the poet uses to examine environmental injustice as do Naumburg’s photos. They sought to capture—in the range of their artistic work drawing upon concrete, lived examples of the consequences of the project from multiple levels and vantage points—a means of offering the most complete picture of the disaster and the consequences of industrial capitalism. These photos and Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead show how employers like Union Carbide, through their greed and indifference, transmute hopeful workers’ shared American dream into suffering and haunted, empty landscapes.

Though Nancy Naumburg abandoned the initially conceived photo-poetic collaboration with Rukeyser, she did remain in touch with the poet about the project. She offered her perspective as a photographer and filmmaker to document the tragedy. “Show…how the whole thing is a terrible indictment of capitalism,” Naumburg wrote to Rukeyser on April 6, 1937.[lxxxiv] That letter, as Moore notes, contains Naumburg’s “‘personal reactions to Gauley Bridge’ and suggested a general outline for the piece” but also “provides some clues about whom the women spoke to and what they saw—a few names, a vignette or two, and a description of the ‘miserable conditions’ of those living with silicosis. ‘Show how the tunnel itself is a splendid thing to look at, but a terrible thing to contemplate’”[lxxxv] Her prescriptions to Rukeyser draw upon her documentary experience explaining a larger issue by drawing upon the building blocks of story, character/subject, setting, and conflict. While a marvel of technology, the tunnel’s awe is offset by the human toll of slow violence. Ultimately, their collaboration, per Kertesz’s assessment, results in an original form and approach while illustrating Black suffering.[lxxxvi]

Her advice is visible in the final product as it indeed includes the components she suggested. The Book of the Dead draws upon its array of documents but also an array of perspectives. Rukeyser names miners like Mearl Blankenship and Arthur Peyton but also includes African American miner George Robinson whose house Naumburg documented. In contrast, the newsreel coverage of the day exclusively focused on white suffering, with Emma Jones becoming the symbol of the Hawk’s Nest disaster. As Moore notes, she “appeared white, beautiful, and hungry. Sometimes she wore a little fur around her neck. She—who had lost three sons and was soon to lose both her brother and her husband—had become the white face of the tunnel’s suffering in the American mind, the media’s ‘Migrant Mother’ of this particular disaster.”[lxxxvii]

Countering that narrative, African American figures (both named and unnamed) are visible throughout the poem with Robinson’s testimony standing most prominently throughout the poem—beyond the section naming him “George Robinson: Blues” as his congressional testimony on the condition is interspersed throughout the poem. Although most of the miners and other figures in The Book of the Dead are white, Robinson is the most constant presence appearing in the most sections of the poem starting with “Praise of the Committee,” which details worker organization helmed by Robinson who “holds all their strength together: / To fight the companies to somehow make a future.”[lxxxviii] His congressional testimony is cited in “The Disease” and “The Cornfield.” This sustained presence keeps the spotlight on the disproportionately effected Black population, although Rukeyser clearly privileges class struggles over racial ones with the full poem. “George Robinson: Blues” is Rukeyser’s failed “attempt to write the poem in the form of a blues lyric,” according to Dayton—the result of versifying the man’s congressional testimony and fitting it to the constraints of rhymed lyrics.[lxxxix] This section notes the inhumane conditions the African American miners, those most likely to undertake the most dangerous work, experienced. The first stanza notes the segregation between towns with “black or brown” men allowed to stand around the sidewalks of Gauley Bridge, though “our town” is “over the trestle” in Vanetta. Robinson notes the slow breathing resulting from walking up a hill or rowing and the inescapability of the white silica dust at the mining site—on the primarily Black worker’s clothes, in their campsites, and even the “milk-white” drinking water provided at the site:

The water they would bring us had dust in it, our drinking water,

the camps and their groves were covered in dust,

we cleaned our clothes in the grove, but we always had the dust.

Looked like somebody sprinkled flour all over the parks and the groves,

it stayed and the rain couldn’t wash it away and it twinkled

that white dust looked pretty down around our ankles.

As dark as I am, when I came out at morning after the tunnel at night,

with a white man, nobody could have told us which man was white.

The dust had covered us both, and the dust was white. [xc]

The ubiquity of the silica dust has a surreal and horrific quality, inverting traditional notions of whiteness as purity and goodness. It disrupts every aspect of the miners’ lives. It covers their clothes despite being washed. It covers their encampments and surrounding vegetation despite the rain. It covers the ground like an eternal sheet of snow brilliantly twinkling— both pretty and eerie. The silica’s ubiquity extends to the human body. The miners constantly consume it by breathing it in and drinking the water provided by Union Carbide. The dust covering the human body also has the effect of erasing difference by making race between the miners indistinguishable. Robinson’s words illuminate the ubiquity of the slow violence Rukeyser illustrates with The Book of the Dead. His words are central to this goal as the poet suggests in an interview: “George Robinson was a real man to me. He speaks for a great many things—not only the dust—much more for the men, and the women, and the children left behind them. It seems to me that social justice comes in here as matter of what is happening to lives—the way in which horizons are opened up the way in which they are thrown away” [xci] The hybrid form of this section and Robinson’s sustained presence illuminates the slow violence and environmental injustice at the heart of Rukeyser’s poem.

Where “George Robinson: Blues” illustrates the ubiquity of dust, sections like “The Disease” demonstrate the effects of silicosis using personal testimony from miners. This is also the case of sections spotlighting white miners like “Mearl Blankenship” who describes his suffering in nightmarish terms:

I wake up choking, and my wife

rolls me over on my left side;

then I’m asleep in the dream I always see:

the tunnel choked

the dark wall coughing dust.[xcii]

Using the array of voices and testimonies available to her, Rukeyser constantly returns to the bodily effects of silicosis. That includes the clinical descriptions by medical professionals, but also the day-to-day effects on the working class miners like Robinson and Blankenship who close their eyes and relive the wall of dust in the tunnel as they struggle to breathe and sleep at night. Rukeyser also emphasizes the human toll of those left behind (as in Naumburg’s photos) for example emphasizing in “Absalom” a mother’s loss of three sons working in the mines: “He said, ‘Mother, I cannot get my breath.’ / Shirley was sick about three months. / I would carry him from his bed to the table, / from his bed to the porch, in my arms.”[xciii] Although the disease afflicted men’s bodies, the poet emphasizes the toll such suffering had on the survivors as well with their loved ones (particularly their wives and children) forced to watch the miners’ growing breathlessness and do the work of their own bodies for the afflicted because Union Carbide refused to acknowledge the issue, having company doctors lie to workers and downplaying the role of their labor in their illness in congressional and legal proceedings.

This corporate indifference is a central thread in the poem’s indictment of capitalism, but it is perhaps most evident in “The Cornfield,” a section describing the relating the corporate coverup of miners’ deaths by unceremoniously burying the bodies of workers who had perished in an unmarked cornfield. The section opens with the scene of a house surrounded by snow (or silica dust) wallpapered with newspaper ads repeating “HEAVEN’S MY DESTINATION, HEAVEN’S MY…HEAVEN…THORNTON WILDER.”[xciv] This wallpaper establishes this setting as a working-class household using newspaper to line the walls. It also gestures towards the inevitable death of the silicosis-afflicted workers buried in this section. Their destination is heaven. Their wallpaper also exclaims the astonishment of the horrors of Hawk’s Nest disaster: “My Heaven!” Especially in death, the bodies of the miners are expendable, violable. Robinson reappears to describe the swift and callous disposal of the bodies of the predominantly African American workers:

George Robinson : I knew a man

who died at four in the morning at the camp.

At seven his wife took clothes to dress her dead

husband, and at the undertaker’s

they told her the husband was already buried.[xcv]

Union Carbide (and its subsidiary Rinehart & Dennis) perceived of these workers bodies at best as waste or—at worst—as evidence based upon the swiftness at which they disposed of the bodies and the utter disregard for any ties they might have to the world outside of the mine. The rest of the poem details the companies’ arrangement with the undertaker, H.C. White, and his actions further desecrating the bodies despite his professional obligation to handle the dead with care. He’s contracted $55 a head to bury the bodies in pine boxes and does so in the family’s cornfield resulting in “His mother…suing him : misuse of land.”[xcvi] As Cherniak notes, “A former friend of White’s insists even [—sometime in the 1980s—] that the undertaker had admitted privately to having arranged 196 clandestine burials,” though the actual number remains unclear to this day.[xcvii] As White transports the workers’ bodies, the “the blind corpses rode /with him in front, knees broken into angles,” according to the rumors circulating in Gauley Bridge. Not only has capitalism robbed the miners of their breath, it’s also resulted in this depraved behavior of an undertaker shoving as many bodies into his vehicle as possible for profit and to sustain the mining industry in the area.

White also attributes the deaths to the miners’ vices on their death certificates, blaming the deaths not on silicosis but on “Negroes who got wet at work, / shot craps, drank and took cold, pneumonia, died. / Shows the sworn papers. Swear by the corn. / Pneumonia, pneumonia, pleurisy, t.b.” The undertaker’s actions insulate the company from liability through misattribution of cause of death. This reflects what Bullard refers to decades later as the “dominant environmental protection paradigm,” which privileges certain races, classes, and workers. It is characterized by actions “trad[ing] human health for profit,” “plac[ing] the burden of proof on the ‘victims’ and not on the polluting industry,” “promot[ing] risky technologies, such as incinerators” (or dry drills in case of the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel) and “exploit[ing] the vulnerability of economically and politically disenfranchised communities.”[xcviii] Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead exposes this paradigm and shows readers its costs, drawing upon Naumburg’s advice to use “a few names, a vignette or two, and a description of the ‘miserable conditions’ of those living with silicosis” in her indictment of capitalism as she illustrates the slow violence gradually destroying the Hawk’s Nest miners’ from their lungs outward while corporations look on with indifference.

Rukeyser’s fused, mosaic forms of the planned photo-poetic conception and the resulting poem are an expression of queer love and collaboration with Naumburg as well as an embrace of the leftist politics these two women shared. The poem itself is queer in it’s transcendence of perceived bounds. By incorporating documents into the poem, Rukeyser was able to deploy prose facts in poetry to develop The Book of the Dead as an indictment of capitalism. Rukeyser declares that “Poetry can extend the document,” and with this poem she takes the documents at her disposal—George Robinson’s testimony, descriptions of the disease’s impact on the human body by doctors and afflicted miners, and local stories recounting the lengths to which Union Carbide treated miners as disposable—and elevates them into a docu-poetic hybrid, emphasizing the facts and her argument against capitalism while emphasizing the human toll.[xcix] In doing so, she challenged the literary establishment as well who took issue with her ambitious approach and political focus. As Adrienne Rich put it, “Rukeyser pushes us, as readers, writers, and participants in shaping world events, to expand our sense of what poetry is about in the world, and of the place of our feelings in politics.”[c] Ultimately, The Book of the Dead redefined the possibilities of poetry and opened the door for Rich and Walker’s generation to embrace politics and pioneer new forms in their work.

Conclusion

Rukeyser’s work also brings to the forefront vectors and temporalities of anti-Black violence, which is as relevant as ever. Not only does The Book of the Dead’s portrayal of slow violence connect in language and historical trajectories to the “I can’t breathe” discourse, it also invites reconsideration of contemporary slow violence and framing of the disaster in terms of a modern environmental justice framework. The lynching victim’s breath in “The Trial” is taken via spectacular violence, and she takes up asphyxiation in The Book of the Dead’s study of slow violence at the hands of capitalism. Recent scholarship has taken up this intersection of slow and spectacular violence, identifying the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests as a rupture point exposing spectacular and slow violence in the U.S. as ubiquitous as the silica dust of Rukeyser’s poem.