Living in fear in Camden and Pennsauken (N.J.) over proposed waste to energy Incinerators, (1970’s- early 1990’s)

by Luis Ramirez

Site Description:

My research topic will be based on the Landfill Crisis of the 1970’s, and how the State of New Jersey decided to build garbage incinerators as the solution to crisis. With locations such as Camden and Pennsauken being hotspots for potential trash incinerators, the road to building the incinerators wouldn’t be an easy one. Backlash from local residents, and delays would make local government officials rethink things. The timeline I want to focus on is the 1980s to early 1990s, from the moment the incinerators were proposed to its final decision. Historical actors will include city officials, environmental agencies, environmental groups, and local Camden/Pennsauken residents. This research will explore the people who were impacted with the crisis, and the proposed incinerator project. I want to find out how the people who opposed the incinerator advocated their cause. What kind of obstacles did they faced? How did the local governments deal with the crisis? This research will raise awareness about the inequality in low income minority areas.

At around 6am on Tuesday, May 29 1990, members of the environmental group Greenpeace made their way into the construction site of a soon to be operating incinerator facility in Camden, New Jersey. They easily took control of a building crane using it to attach their banner onto a smokestack. No force was needed as no one was present at the construction site. A simple white banner with black text font flew high over the site, with a message that read: “Gov. Florio, Don’t burn N.J.” directed towards the governor of New Jersey at the time. It could be seen from across the river in the city of Philadelphia as the smoke smack was 367 ft tall. Greenpeace hoped to get attention from the Governor, in hopes of getting the Camden Incinerator project canceled.1 Without the right connections, the project would be impossible to cancel.

Many similar protests were happening all over New Jersey. In the 1980’s, New Jersey was going through a garbage crisis. Landfills had run out of space and New Jersey’s solution was to build incinerators throughout the state to handle the garbage crisis, and selected sites included Camden and Pennsauken. From the moment the incinerators were proposed, citizens from these towns quickly opposed waste to energy incinerators because of social, economic and environmental factors that would have a negative effect on their community. The people were aware of the outcome of these incinerators, and they were willing to fight back. It was brought to the attention of local governments, and every town government had a different response. In the end, most towns in NJ were successful in canceling proposed incinerators. Unfortunately, for Camden, the people were not able to prevent the incinerator from being built.

If local governments knew about the risks, why was it proposed in the first place? Once they were proposed, how did the people fight back? If most towns did not go through with the plans, why did Camden fail and Pennsauken succeed in eliminating their incinerator project? In this situation, activism brought people together in the fight against incinerators. Their presence helped influence the final decisions on the incinerator projects.

This paper will take place during the 1970’s to early 1990’s, explaining the landfill crisis in New Jersey, and how it influenced the incinerator projects in New Jersey, specifically Camden and Pennsauken. In addition, the paper will examine the social and economic conditions that facilitated the incinerators. The paper will then show how people’s reactions shape the incinerator proposals. Finally, the paper will conclude with the successes and failures, and what ultimately led to these decisions and why. The facility in Camden was built because of economic reasons. Camden failed because of demographic differences including race, class, and education levels that limited the ability to block the proposal. As a result, the citizens of Camden suffered environmental harm.

Camden and Pennsauken’s Historical Past & The New Jersey Landfill Crisis

Today, Camden is known as a low income minority city. Although at one point in history, during the 19th and early 20th century, Camden was a booming industrial city known for manufacturing materials such as metals, petroleum, leather and other sources. It welcomed companies such as Campbell’s Soup and RCA Victor making it an important area for manufacturing. It is located alongside the Delaware River making it easier to transport goods. Additionally, the city of Philadelphia is right across the river, making this area a powerhouse for manufacturing. In the 19th and 20th century, Camden was a place where working class people lived, they could go to work and be home all within the city.2

Pennsauken, also located near the Delaware River, became a center for small business thanks to its direct access to the Philadelphia metropolitan area. In the 19th century, Pennsauken was mostly made up of farmland but by the mid 20th century it was converted into residential developments making this a popular destination for suburbanization.3

In the 1930’s, Camden and Pennsauken went through an economic decline due to the Great Depression that crashed the stock market. Not only did it impact the Philadelphia metropolitan area, it affected the whole country. Unfortunately, many people lost their jobs and homes. The federal government created a program called Home Owners Loan Corporation, that financially helped save homes and businesses by giving loans.4 However, Black people were least likely to be given loans, as the HOLC was strict and created maps that segregated neighborhoods by color and letter grading. This was one of the first signs of economic inequality in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Suddenly, America was at war, and the economy rose back to the top, creating job opportunities for Black Americans. World War II brought Camden economic success, but it wouldn’t last long. After the war ended, many companies like RCA Victor decided to leave Camden, leaving many people without jobs.5

It was around this time, many Black Americans were moving into the industrial cities such as Camden, while Whites were fleeing into suburban neighborhoods like Pennsauken. This left many northeastern cities such as Camden in economic despair, many working class people left the city in search of a better life. Within the next decades, the results of deindustrialization and white flight left Camden with limited sources. It negatively impacted the local economy, poverty rose and crime increased.

According to a Census report on the city of Camden, by 1980, Camden was a majority Black city. Whereas 20 years before that, whites were the majority of the population. More importantly, the year 1960 was the peak for industrial jobs, immediately followed by a dramatic decline in jobs.6 This may have to do with white flight, racial discrimination and the civil unrest happening around the country. Moreover, Camden’s reputation as a place for working class families to live was destroyed by poverty and crime, all of this negatively affecting Camden’s economy.

In the 1970s, the US was going through a garbage crisis. Landfills were once an efficient and beneficial method of solid waste disposal, but many US states had run out of landfills to store their garbage, and this also impacted New Jersey. It was a nationwide problem, specifically the northeastern part of the United States. New Jersey at one point attempted to send their garbage to the next state over, Pennsylvania, but they rejected NJ’s garbage, as they wanted nothing to do with it as they had their own garbage issues. Luckily, the US government passed a bill that made it easier for states to come up with a new garbage plan.7 By the 1980s, New Jersey decided to order all of its 21 counties to build an incinerator to deal with the ongoing crisis.8 At first, many local governments were in favor of the incinerator. In return, many New Jersey residents retaliated against the idea of garbage incinerators, in fear of the harm it would have on their lives.

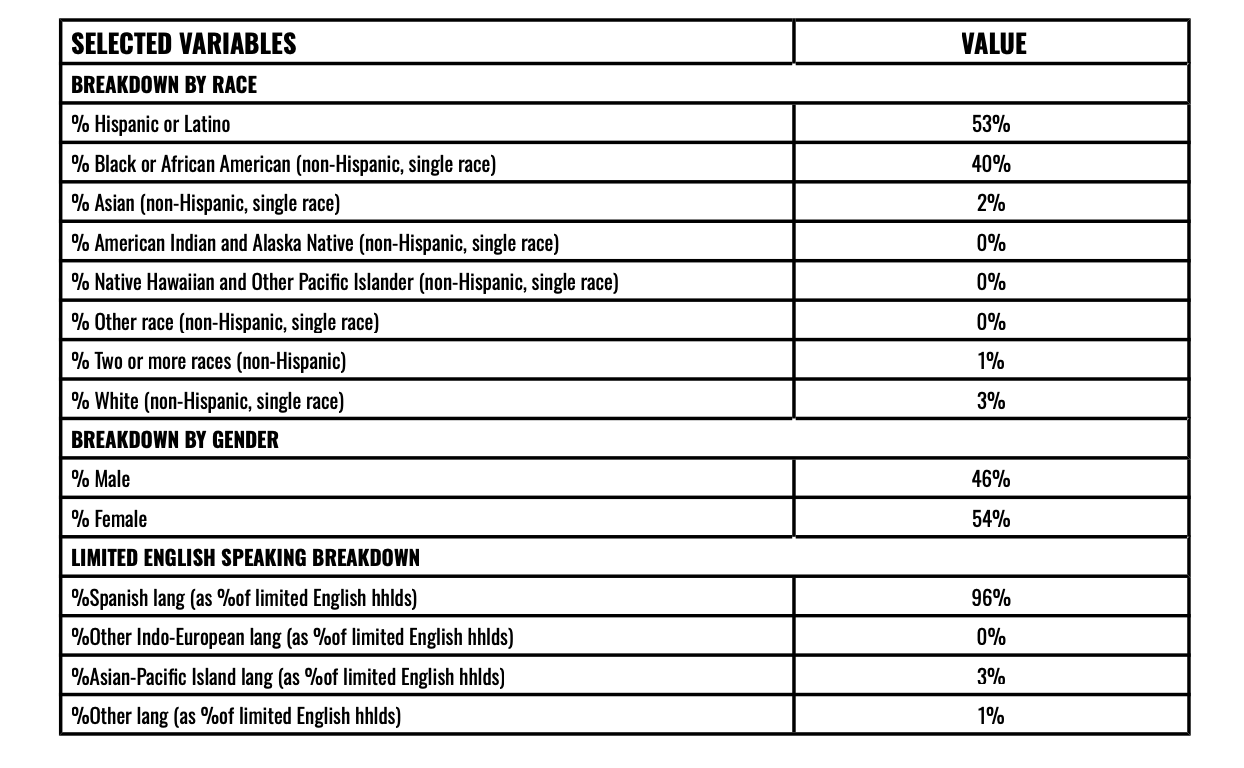

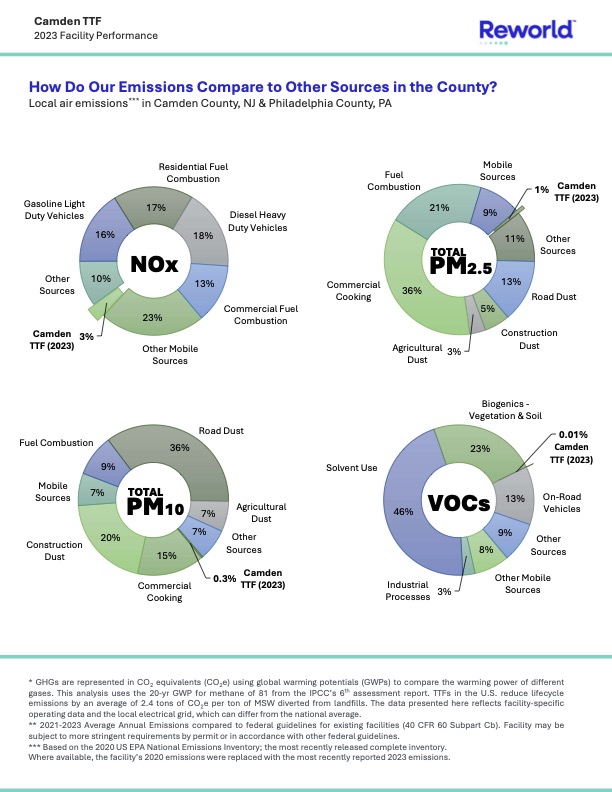

Camden Demographics

Camden Mayor Randy Primas knew the incinerator could be a new chapter of economic success in Camden. For Primas, it was all about making money, he knew the potential the incinerator had, possibly influencing other industries to come to Camden.9 By the mid 1980’s, he was ready to invest on the project. Primas said, “Camden, for example, will get a rebate of $1 per ton of trash burned in its incinerator. Also, the cost to the city for transporting its garbage to the plant will be lower than the current cost of shipping the trash to kingsley”. 10 Up until October 1985, all towns in Camden County had dumped their garbage in the Kinsley landfill located in Gloucester County, New Jersey. Unfortunately, Gloucester County no longer wanted Camden County’s trash and ordered them to take it elsewhere like Philadelphia. As a result Camden mayor Randy Primas became more motivated, and had to act quickly and get a plan together if he wanted his city to benefit from the incinerator. Primas knew he could make a profit from the trash turned energy. He also knew other towns would be in favor of sending their trash to Camden, as the shipping cost to the site would be cheaper.

Before the project was started, many citizens were curious about the full plan. They wanted to know as to where the Incinerator would be built, if it would bring garbage from outside New Jersey, how much it would cost for a feasibility study on potential sites, and how harmful were the dioxins that would be released from the smokestacks. Camden Mayor Randy Primas and his administration did not have any official answers, which frustrated the citizens of Camden. The residents of Camden had been trying to set up a meeting with town officials to discuss this issue, but were not given an official date. This annoyed residents with how incompetent the local government was with the situation. Reverend Doyle, a Catholic Pastor from the Camden community said, “The questions need to be asked. The trust has to be there. I know if this were a block off Route 70, there would be an informational meeting. I know it!”11 Reverend Doyle’s innuendo may be referring to the people of Camden possibly dealing with systemic racism. He believed that if the incinerator was proposed elsewhere such as near Route 70, the local government would have informed the community before any actions were taken. In fact, the majority of the towns that pass along Route 70 have a high percentage of white people. Towns such as Pennsauken, Cherry Hill, Toms River, and Wall Township have a high percentage of white people.

After all, in 1980, half of the population in Camden was Black being at 53%, also Spanish origin was 19.2%.12 This indicates that the city of Camden was more likely to be racially disadvantaged. Cities that are racially disadvantaged tend to have a limited access to quality education. In 1980, 58.6% of people aged 25 or more in Camden did not graduate from high school, 27.3% graduated from high school, and only 4.8% were college graduates.13 People with less education are most likely to be working minimum wage jobs, and most likely have a second job. They’re most likely to be working all day, preventing them from having a life outside of work. Which also indicates that they don’t have time to be involved in their community. If 58.6% of the people living in Camden at that time did not graduate from high school, this indicates that the lack of education prevented them from mastering the basics of science. Which also prevented the majority of Camden residents to fully comprehend the significance of the Incinerator issue, and the environmental impact it would have on the city, or what a dioxin is.

As mentioned before, Camden had a Spanish population of 19.2%. This indicates that there were potential language barriers within the community. According to the 1980 US census, 21.9% of people living in Camden spoke a language other than English at home.14 This also indicates possible isolation from the rest of society, you have a certain demographic of people whose primary language is not English. On top of that, the Spanish speakers were probably not being informed as to what was going on in their community, and were least likely to attend a town hall meeting. Even if they were to attend a meeting, there probably wasn’t a translator for them because Camden had limited resources.

Nevertheless, the Camden community still had people that were not going to let the city government take control of their lives. They were going to meet with the local government to convince them to delay any plans related to the upcoming incinerator. Regardless of the meeting, Mayor Primas and his administration were already getting ready to perform preliminary research on potential sites. The study would cost about $40,000 to $50,000. Primas was in favor of the incinerator as he knew it could bring economic benefits to the city of Camden, and a permanent solution to the landfill crisis.

Although, the incinerator project could bring economic growth to Camden. There is no doubt that Primas’ own citizens could still be left in economic despair, there was no certainty the project could benefit citizens. According to a 1980 census, 17.9% of the civilian labor force in Camden were unemployed. This percentage of unemployment may be due to the fact of the industrial decline in Camden. Also according to the 1980 census, 32.3% of family Income in Camden was below poverty level. In 1980, the median family income in the United States was $21,020. While Camden’s median family income was only $10,607.15 These numbers definitely contribute to the idea of low income communities being targets of environmental hazards. The people of Camden were obviously taken advantage of because of their social status, and their limited access to resources. Since a high percentage of Camden residents were poor, and as mentioned before, 32.3% of family income in Camden was below the poverty level, this would indicate that residents could not afford to give the basic necessities to their families. What if the incinerator was their last chance to get out of poverty? Mayor Primas promised to bring Camden back to life by redeveloping the industrial neighborhood and restarting its economy.

Residents in Camden knew it was a big risk, as they had a hard time trusting their own government due to bad experiences in the past.

Years prior, an investigation was called to examine untreated raw sewage being dumped into the Delaware River. It was discovered that the Camden sewage treatment plant had broken parts and was all busted up. The Federal Environmental Protection Agency knew about the catastrophe for some time but no action was taken. Also, State health officials were being neglectful of the sewage situation. No one was being responsible, and we can only imagine the foul smell of raw sewage throughout the city of Camden. Local citizens insisted the sewage system be fixed, people were aware this was a public health and environmental issue.16 Camden city officials did not notify the public about the failing sewage system beforehand, they were aware about the raw sewage being dumped into the Delaware River, but didn’t take immediate action to clean it up. It is clear with irrefutable evidence that local government officials and agencies were thoughtless on how to manage toxic waste.

Similarly with the Incinerators, environmentalists warned people about the harmful air emissions it would produce, containing dangerous toxics. On the other hand, supporters of the project insisted that the incinerator would be safe. They ensured it would be monitored and would follow environmental guidelines. Studies had been conducted in the early 1980’s in Camden and other nearby industrial cities. Studies were designed to find what toxic substances people were being exposed to. What they found was that people in these areas were being exposed to lethal toxicities. Furthermore, it was discovered that lung cancer was more common in New Jersey than any other place in the United States, and chemicals such as Arsenic, Beryllium, Mercury, and Dioxins were the cause of long term health problems.17 These chemicals are also found inside garbage incinerators.

While the city government did not reconsider its incinerator plans, after the studies were made public. Groups were formed to fight the development of incinerators all over the state of New Jersey. One of these groups was GrassRoots Environmental Organization, Madeline Hoffman was the leader of the organization, Hoffman’s organization teamed up with Greenpeace on a mission to ban the construction of incinerators, they had people sign a petition that was sent out to state officials. Together they organized protests in all construction sites for incinerators including Camden.18 Other environmental groups who would join the fight would be the South Camden Action Team (SCAT) and Citizens Against Trash to Steam (CATS). Together they would fight against the Camden city council.19

Pennsauken Demographics

Pennsauken was fighting alongside Camden against the Incinerator projects. Similar to Camden, Pennsauken residents feared the incinerator’s emissions would be extremely toxic to the air. Just like Camden, Pennsauken was involved in the garbage crisis. Pennsauken’s reasoning for needing an Incinerator was not about its economy, rather a solution to the landfill crisis. The incinerator was expected to burn 500 tons of garbage a day; it was less than Camden’s which was expected to burn 1,050 tons of garbage a day.20 The town of Pennsauken’s biggest concern was the environment. If the town was going to have an incinerator in their area, they wanted to make sure that it was safe for the community. At the same time, Pennsauken was in desperate need for an Incinerator because the trash was piling up and there was no space left, an Incinerator was the solution for some people. Those who supported the Incinerator were trying to solve the problem with Pennsauken’s landfill garbage; there were fears the toxins would harm the environment affecting the nearby groundwater and Delaware river.

Although Pennsauken was on the same boat as Camden regarding the landfill crisis. Let it be known Pennsauken’s Black population was 7.7% and its Spanish origin population was 1.5% according to the 1980 US census.21 Compared to Camden, this data indicates that Pennsauken’s population was majority white. According to the 1980 US census, 6.8% of Pennsauken civilian labor was unemployed, with 4.5% of families income below poverty level. However, $21, 891 was the family median income in 1980,22 which is much higher than the US median family income of $21,020. This indicates that the people of Pennsauken were doing better financially than Camden residents. Looking at the median household income in Pennsauken, it gives a sense that the people living here were financially stable. Although there is some poverty in Pennsauken, the majority of the residents were able to afford basic necessities. Also if residents in Pennsauken were earning more money than the US median family income, they were more likely healthier.

On a different note, being financially stable most likely meant that they had high quality jobs. It is known that people who are more educated, are offered better jobs, and are most likely to be offered a higher salary than those who have less education. According to the 1980 US census, those who were living in Pennsauken over the age of 25 were 64.7% high school graduates, 10.5 % completed 4 or more years of college.23 This indicates that Pennsauken was a more educated society. On top of that, the people definitely contributed to the local economy. It is no surprise that Pennsauken residents were more involved when it came to facing environmental issues such as the Incinerator. They probably had connections with a larger network of people with different occupations such as doctors, lawyers, politicians, scientists, law enforcement that allowed them to see the ins and outs of their society. This would allow them to have better knowledge of the Incinerator issue, as someone probably had information about it.

Many people in Pennsauken opinionated in regard to the Incinerator, most of them saying it was wrong. Anthony Vellucci, a resident from Pennsauken had this to say about it in the Courier Post, a local newspaper based in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, “If the Pennsauken Incinerator is so great, why aren’t the towns dumping in Pennsauken fighting to have one near their own high schools? Pennsauken has done more than its share of garbage handling for other towns. Isn’t it time someone else took a turn? We have enough unhealthy situations without adding an Incinerator.”24 Vellucci was probably referring to past situations such as Camden’s Sewage Treatment Plant dumping toxic waste into the Delaware River, impacting Pennsauken as it is located alongside Camden and the Delaware river.

Pennsauken residents worried about the Incinerator as there was uncertainty on the health risks.The citizens main concern was the dioxins the incinerator would release into the air. Pennsauken citizens were aware of the dioxins that would be produced, if the Incinerator’s temperatures were too low. They were concerned about its harmful potential to the human body. The company responsible for the Pennsauken project, Ogden Martin, mentioned that the incinerator’s emissions were safe, comparing numbers to their plant in Oregon. Even after getting a second opinion from an environmental engineer who worked with Ogden Martin, there was still uncertainty on the risks. The Federal Environmental Protection Agency also took a look into the Incinerator’s health risks, yet they did not know how to label the risks as there was not enough scientific information.25 The sad thing is that no one had official answers. Everyone from the federal EPA to the New Jersey State Health Department knew that the chemicals were toxic, and had tremendously horrific long term effects on human health. Yet different agencies had different ways of evaluating and classifying the levels of the dioxins. Just like in Camden, it seemed as though government officials were being unwary with Pennsauken’s citizens on how to manage toxic waste.

The other problem that Pennsauke residents had was the reliability of the technology of its time. They were aware the technology that would be used for the Incinerator would only last 40 years.26 The lifespan of an incinerator is half a person’s life, but the environmental damage could outlive both the Incinerator and a human’s life. Furthermore, the technology would eventually be outdated someday, there’s a chance that it would have incompatibility issues, and it wouldn’t be up to date with the latest regulations. Even if the company was to add pollution control equipment it cost more money to maintain.27 Citizens knew it was not beneficial economically and environmentally.

In Pennsauken, there were views from both sides of the Incinerator’s potential environmental impact, the pros and cons. The town came together to discuss this matter in a meeting with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Local environmental organizations such as Stop the Incinerator Now (SIN) urged the DEP to find better ways to deal with solid waste disposal, one being recycling. They asked the local government to create programs that could promote recycling and open facilities where the trash would be handpicked and divided. SIN even insisted that it would cost less money than operating the Incinerator. However, SIN felt that the local government disregarded their views on this matter, and were still in favor of the Incinerator. Pennsauken residents were met with other communities around the state who also voiced their concerns. Pat Maloney, a member of the Allied Citizens Opposing Pollution, had this to say, “Our State does not go out of the way to make recycling easy. If they build all these incinerators, there’ll be no incentives to recycle” 28

After environmental groups gave their opinion, the local government responded with how there was nothing to worry, and the builders, Ogden Martin Systems Inc, would build a pollution control device. Yet, members of the community were still worried of the dioxins that would be released from the smokestack. What frustrated members of the community was the evidence provided to the public from scientists regarding the pollutants, and yet local government officials ignored it.

Wins & Losses

The deadline was getting closer, all garbage related projects would have to be completed by 1992. In the late 1980’s, tensions were growing from all sides. New Jersey wanted Camden to also build a new landfill, but Camden city officials advised the state that there was only space for an incinerator. New Jersey was still going forward with its original plan of building garbage incinerators in each county.29 Some government officials insisted New Jersey consider regional solutions to the solid waste, instead of building incinerators in each county. Nevertheless, many people insisted that New Jersey deal with its own garbage problem within the state.

Disputes between the contractors and government agencies would delay the construction of the incinerators. The Federal Environmental Protection Agency wanted Pennsauken’s contractors, Ogden Martin, to reevaluate the company’s technology as the pollution control equipment had not passed inspection.30 The technology did not meet the federal standards, and the federal EPA insisted the contractors fix it, before continuing construction. In addition, it would cost almost 2 million dollars to fix it.

However, other people wanted more than the equipment getting fixed, they wanted the project to be scrapped completely. Protesters would even take as far as going to the New Jersey governor Kean’s home. The purpose of the protest was to demonstrate to the governor that recycling and composting could get the same job done as an incinerator, but done in a more eco-friendly way.31 This was important for the environmental groups because they wanted the governor to know that this would impact their health and the environment. There were local politicians who sided with the environmental groups, such as John A. Rocco, Republican of Cherry Hill, who believed that there were alternative technologies but the DEP only cared about meeting deadlines.32As mentioned before, all garbage related projects would have to be completed by 1992. DEP had no time to look for other options. The goal was to close the majority of the landfills in New Jersey, to not rely on any out-of-state landfills and open the Incinerators for business.

Then, Camden County officials began to question whether or not it was necessary to have two incinerators, when one incinerator could handle all of the county’s garbage. If any changes were to be made it would have to be taken to Camden County Solid Waste Advisory Council (SWAC), and then to the state DEP to officially be approved.33 The project that SWAC wanted to cancel was Pennsauken, which comes to no surprise. In addition, the financial costs for the Pennsauken project outraged the citizens. They knew their taxes would exponentially increase.34 It’s interesting that Pennsauken residents did not want to pay those unnecessary taxes, these were middle class people who were able to afford almost everything. However, no one wants to see their community get destroyed.

Pennsauken’s project would then be postponed as government officials passed a bill to delay construction of garbage incinerators. The problem was that Pennsauken was in debt. Besides Pennsauken, it would cost about $3 billion dollars to finish the construction of all incinerators in New Jersey.35 Therefore, most politicians were not sure as to whether or not they should go through with the original plan. At the same time, researchers would be conducting environmental and financial research regarding the incinerator projects. The biggest problem for the state government was to make sure there was enough capital to keep the incinerators operating smoothly.

Then in February 1990, the newly appointed Governor of New Jersey, Jim Florio stopped issuing permits for new garbage incinerators.36 Unfortunately, this permit was not in effect for Pennsauken or Camden. As the Previous Governor had already approved the permits during his time in office. Legal challenges slowed down the construction of both sites. Both town governments wanted to make sure the contractors were able to reduce the price for dumping fees, but the contractors never gave them an official word.37 This created tension between Foster Wheeler Corporation and Camden; Ogden Martin Corporation and Pennsauken. The factors that influence its pricing are not controlled by the company. The town governments wanted to take the easy way out, by not paying the full price, they wanted to use shortcuts. Even though environmental protesters presented recycling projects to their local government officials, they didn’t take it into consideration.38 The environmentalists even explained that it would cost less money for the recycling project to function.

At the same time, there was talk of officially banning the Pennsauken project. Under a new agreement, the Pennsauken project would blend into Camden. Camden would help pay off Pennsauken’s debt by asking investors for more money.39 In return Camden’s economy would eventually take off. Yet there were other problems in Camden such as poverty and crime. Although it would have us believe that Camden would benefit from the incinerator, this was a big financial risk. However, the biggest risk was the people’s health. Everybody was warned ahead of time about the dangerous toxics, and yet the only thing that was really stopping the incinerator from being built was the money. The politicians never cared about the people, whether it was Camden or Pennsauken.

Overall, Pennsauken was able to find a solution to its landfill crisis by having it sent next door, being Camden. Pennsauken was never in a true economic crisis, whereas Camden was in desperate need for a revitalization of its economy. Camden mayor Primas ensured that the incinerator would bring economic benefits. Yet two decades later, things seemed a little hazy in Camden. According to a 2000 census, the median family income in Camden was $24,162.40 While the US median income in 2000 was $42,148. Shockingly, 32.8% of family Income in Camden was below the poverty level.41 Two decades after Primas announced the incinerator plans, the community’s financial situation did not get better. It only benefited the city’s economy, not the people.

As a result, the Camden incinerator ultimately impacted people’s health in both the city of Camden and the town of Pennsauken. According to the American Cancer Society of New Jersey & New York, cancer rates were higher in the southern part of New Jersey impacting counties such as Camden. It also mentions that lung cancer is the leading cancer in Camden county, both exceeding the state average for men and women.42 The number of cases for diseases went up by 2.6% since 1994, this is most likely caused by the Camden Incinerator. This was around the same time it began operating.

In the end, no one really won, these statistics show the overall effects it had on the people of Camden County. There’s this saying that goes: health is wealth. It’s true. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you do, you’re nothing without your health. Unfortunately, there are people who put a price tag on health by overcharging others with medical bills and health insurance. After looking at the statistics, we know that Camden residents would be least likely to afford medical help. Camden is a city with a high percentage of poverty. If the Camden local government had just invested into people’s health, the city would be in a much better position.

The bigger Significance

At around 6am on Tuesday, May 29 1990, members of the environmental group Greenpeace made their way into the construction site of a soon to be operating incinerator facility in Camden, New Jersey. They attached their banner onto a smokestack. A simple white banner with black text font flew high over the site, with a message that read: “Gov. Florio, Don’t burn N.J.” directed towards the governor of New Jersey at the time. In hope to get attention from the Governor, in desire of getting the Camden Incinerator project canceled. In fact, we know that the project was never canceled and the city would eventually face the consequences.

Of course for some people like Randy Primas it was about the money, he was willing to risk the lives of his own citizens In favor of having other industries come to Camden and create an economic boom. However, other politicians saw the bigger picture and they realized building incinerators throughout the state was only going to create new problems.

Before local governments knew about the risks, it was originally proposed to solve the landfill crisis. After finding out about the incinerator’s potential negative effects, people decided to oppose it. Cities like Camden did not back out, and decided to go through with the plans. Camden failed because of demographic differences including race, class, and education levels that limited the ability to block the proposal. Unfortunately, for Camden, the people were not able to prevent the incinerator from being built.

Endnotes

- The Associated Press, “A message for Florio: Environmental group stages protest at incinerator site,” Daily Journal (Millville, NJ), May 30, 1990. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fmay-30-1990-page-2-32%2Fdocview%2F2382634788%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Diane Sicotte, “The Rise of Industrial Philadelphia,” In From Workshop to Waste Magnet: Environmental

Inequality in the Philadelphia Region, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 67.

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1gn69sc.10

- William McMahon, “Pennsauken,” South Jersey Towns-History and Legend, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1973), 276-77.

- U.S. Congress, “United States Code: Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933, 12 U.S.C. §§ 1491-1468” 1934, Image, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/uscode/uscode1934-00101/uscode1934-001012012/uscode1934-001012012.pdf (accessed April 27, 2025)

- Diane Sicotte, “The Rise of Industrial Philadelphia,” In From Workshop to Waste Magnet: Environmental

Inequality in the Philadelphia Region, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 76.

- Howard Gillette, “Camden Transformed,” In Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal ina Post-Industrial City, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhqkq.7

- Congress.gov. “S.2150 – 94th Congress (1975-1976): Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976.” October 21, 1976. https://www.congress.gov/bill/94th-congress/senate-bill/2150.

- State of New Jersey, “Department of Environmental Protection, Certification of Approval With Modification of The Camden County District Solid Waste Management Plan”, July 1980. https://www.nj.gov/dep/dshw/recycling/admentme/Camden/060680cert.pdf

- Andrew Hurley, “From Factory Town to Metropolitan Junkyard: Postindustrial Transitions on

The Urban Periphery,” Environmental History 21, no. 1 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24691539

- Dianna Marder, “They Say It’s Time For Tough Talk on Trash,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), Nov. 27 1985. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fnovember-27-1985-page-146-150%2Fdocview%2F1849891745%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Ken Shuttleworth, “Activists Work to Delay Siting of Trash-Burning Facility,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, NJ), Dec. 18, 1984.https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fdecember-18-1984-page-14-46%2Fdocview%2F1919149898%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter B, General Population Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 9. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1980/volume-1/new-jersey/1980a_njab-03.pdf

- “Output for Camden City, NJ: Percent of Persons Aged 25 or More by Highest Educational Attainment” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Policy Development and Research, State of The Cities Data Systems Census Data, 1980) https://socds.huduser.gov/Census/education.odb?msacitylist=6160.0*3400010000*1.0&metro=msa

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter C, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 17.https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1980a_njC-01.pdf#[0,{%22name%22:%22FitH%22},813

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter C, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 26. https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1980a_njC-01.pdf#[0,{%22name%22:%22FitH%22},813

- “Investigate Camden’s Raw Sewage Miscue,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, New Jersey), Jan. 16, 1976.https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fjanuary-16-1976-page-12-66%2Fdocview%2F1918417257%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Ronald Harkov, “Toxic Air Pollutants in New Jersey: A Preliminary Assessment of the New Jersey Program for Airborne Toxic Elements and Organic Species (ATEOS)”, (New Jersey D.E.P. Information Resource Center, October 1983) 18-19, 43. https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/32625/PDF/1/play/

- Jay Romano, “Essex Incinerator: New Look at Old Debate,” New York Times, Dec. 30, 1990. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a3SC9-S4T0-003Y-K174-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=D7NH5251644

- Diane Sicotte, “Saving Ourselves by Acting Locally: The Historical Progression of

Grassroots Environmental Justice Activism in the Philadelphia Area, 1981–2001,” In Nature’s Entrepot: Philadelphia’s Urban Sphere and Its Environmental Thresholds, eds. Brian C. Black and Michael J. Chiarappa (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), 243. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.11249276.14

- The Associated Press, “A Message for Florio: Environmental Groups Stages Protest at Incinerator Site,” Daily Journal (Millville, New Jersey), May 30, 1990. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fmay-30-1990-page-2-32%2Fdocview%2F2382634788%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter B, General Population Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 15. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1980/volume-1/new-jersey/1980a_njab-03.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter C, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 31.https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1980a_njC-01.pdf#[0,{%22name%22:%22FitH%22},813

- U.S. Census Bureau. “1980 Census of Population: Volume 1, Characteristics of the Population, Chapter C, General Social and Economic Characteristics, Part 32: New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 22. https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1980a_njC-01.pdf#[0,{%22name%22:%22FitH%22},813

- “Noteworthy: If Trash to Steam is Wrong Approach in Pennsauken, What’s Right?,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, New Jersey), Nov. 2, 1985. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fnovember-2-1985-page-6-40%2Fdocview%2F1923343198%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Shira Birnbaum, “The Burning Questions Surrounding The Incinerator,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, New Jersey) Oct. 29, 1987. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Foctober-29-1987-page-49-72%2Fdocview%2F1919270651%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Shira Birnbaum, “A Need for Information: Short-Term Technology but Long-Term Results,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, New Jersey) Oct. 29, 1987. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Foctober-29-1987-page-49-72%2Fdocview%2F1919270651%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626

- Stephen Barr, “Incinerators and Pollution: Thorny Issue,” New York Times, Mar. 26, 1989. https://www.proquest.com/docview/110339180?parentSessionId=gugI0WDI9S3SMgaq27P%2Flbfgn%2BX2t%2FwuhWfSdsF51vk%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Andrew Maykuth, “Trash-to-Steam a Burning Issue for Pennsauken,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), Jan. 27, 1988. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fjanuary-27-1988-page-94-160%2Fdocview%2F1853428761%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

- Stephen Barr, “Incinerators and Pollution: Thorny Issue,” New York Times, Mar. 26, 1989. https://www.proquest.com/docview/110339180?parentSessionId=gugI0WDI9S3SMgaq27P%2Flbfgn%2BX2t%2FwuhWfSdsF51vk%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Stephen Barr, “Incinerators and Pollution: Thorny Issue,”New York Times, Mar. 26, 1989. https://www.proquest.com/docview/110339180?parentSessionId=gugI0WDI9S3SMgaq27P%2Flbfgn%2BX2t%2FwuhWfSdsF51vk%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Press Staff Report, “Protesters Rally Near Kean’s Home,” Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, NJ), Feb. 7, 1988. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2011859431?parentSessionId=x3O2CR6jMJK6xUwNNo9MSz2ejfe7rhMJnB1mYdeNwZg%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Stephen Barr, “Alternatives To Incinerators Are Sought,” New York Times, Jan. 8, 1989.https://www.proquest.com/docview/110228264/pageviewPDF/8340D60DC9384465PQ/1?accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Bill Shralow, “Freeholder: Panel Ready To Scrap Plans for Pennsauken Incinerator,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, NJ), Jan. 21, 1990. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2841935438?parentSessionId=8vnsg6iWJkFnV0ONPAK0VhgIrTU5v65pWJWE19iDMJ0%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Denice Ferrarelli, “Group, Towns Plan Continued Fight Against Pennsauken Incinerator,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, NJ), March 6, 1989.https://www.proquest.com/docview/1919307481?parentSessionId=xnhgKr0Ur1kKqVflEG7YHyYmINsr1pyo8QPKiy3t%2B8k%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Ted Hampton, “N.J. Assembly Panel Passes Moratorium On Construction Of Incinerator Plants,” Bond Buyer (New York, NY), Sept. 29, 1989. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a3S89-50R0-0004-23K6-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=D7NH5251644.

- Lee Seglem, “Florio’s Ban On Garbage Incinerators Sparks Reaction,” Daily Journal (Millville, NJ), Feb. 2, 1990. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2382622228?accountid=13626&parentSessionId=08IC%2FYTJtqlQPuDUktk%2FuTcNPkXw1IWaOU%2Fz66O5EEg%3D&sourcetype=Newspapers

- Bill Shralow, “Firms Building Incinerators Reviewing Fee Limit,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, NJ) Mar. 9, 1990. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1919346648?parentSessionId=S%2BoPNYLvAsDrP%2BjkqNKkB7LhIGi7FeWqxVw3UabYfPY%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- “Give Us A Moratorium, Not A Four Month Phase,” Courier-Post (Cherry Hill, NJ), Apr. 10, 1990. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1919353135?parentSessionId=K3p7sjPuW0hFsCsu1hOwZSV9TAO5cpSoQPAum07Qixk%3D&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

- Steven Dickson, “Moody’s and Standar & Poor’s Slash Ratings on Pennsauken, N.J., Authority,” Bond Buyer (New York, New York), Dec. 6, 1990. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a3S89-5N20-0004-203N-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=D7NH5251644

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2000 Census of Population and Housing, Summary Social, Economic, and Housing Characteristics, PHC-2-32, New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2003), 88.https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2003/dec/phc-2-32.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. “2000 Census of Population and Housing, Summary Social, Economic, and Housing Characteristics, PHC-2-32, New Jersey” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2003), 143.https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2003/dec/phc-2-32.pdf

42. “The Cancer Burden In New Jersey” (American Cancer Society, New Jersey & New York, 2012) A-7. https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/State%20Documents/NJ_Cancer_Burden_Report_2012.pdf

Primary Sources:

1. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fdecember-18-1984-page-14-46%2Fdocview%2F1919149898%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

This is a newspaper article written by the Courier-Post on December 18, 1984, regarding the protests of the designation of a potential site for a garbage incinerator. I believe that this source will be useful, as it provides a negative view on the incinerator from the environmental activist perspective. It shows how the protesters believe there’s a lack of trust in the government because there’s no communication.

This is a newspaper article written by the Philadelphia Inquirer on May 13, 1990. This article gives a good description of how the garbage incinerator would operate in Camden. It provides a unique illustration of the incinerator showing the technical side of things; the process of trash to steam creating electricity. It gives a good insight into the operation inside the facility. In the months leading up to the opening date of the new garbage incinerator, many people in the Camden community had questions and concerns about the new facility- one of them being how the incinerator would function.

3. https://www.nj.gov/dep/dshw/recycling/admentme/Camden/060680cert.pdf

This document from the state of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection dated July 17, 1980. The document explains shortages of landfill disposal capacity impacting Camden County. Camden County would use the facilities in Burlington and Gloucester Counties temporarily. This would only be one of the main reasons as to why Camden built its own garbage incinerator, to reduce the amount of waste in landfills. I believe this source can help better explain the origins of the incinerator- what led to its creation.

4. https://www.nj.gov/dep/dshw/recycling/admentme/Camden/120591cert.pdf

This is a document from the state of New Jersey Department of Environmental written on December 5, 1991. This is a good source that shows the type of permits and regulations the South Camden Incinerator had to follow for air pollution control. It will help my readers understand the complex situation, the layers to getting things approved. For example, this source talks about designated truck routes to the incinerator, they have to comply with certain streets weight limit standards. But I can also use this source to question how the incinerator violates the DEP’s regulations, and why citizens want stricter regulations for the incinerator.

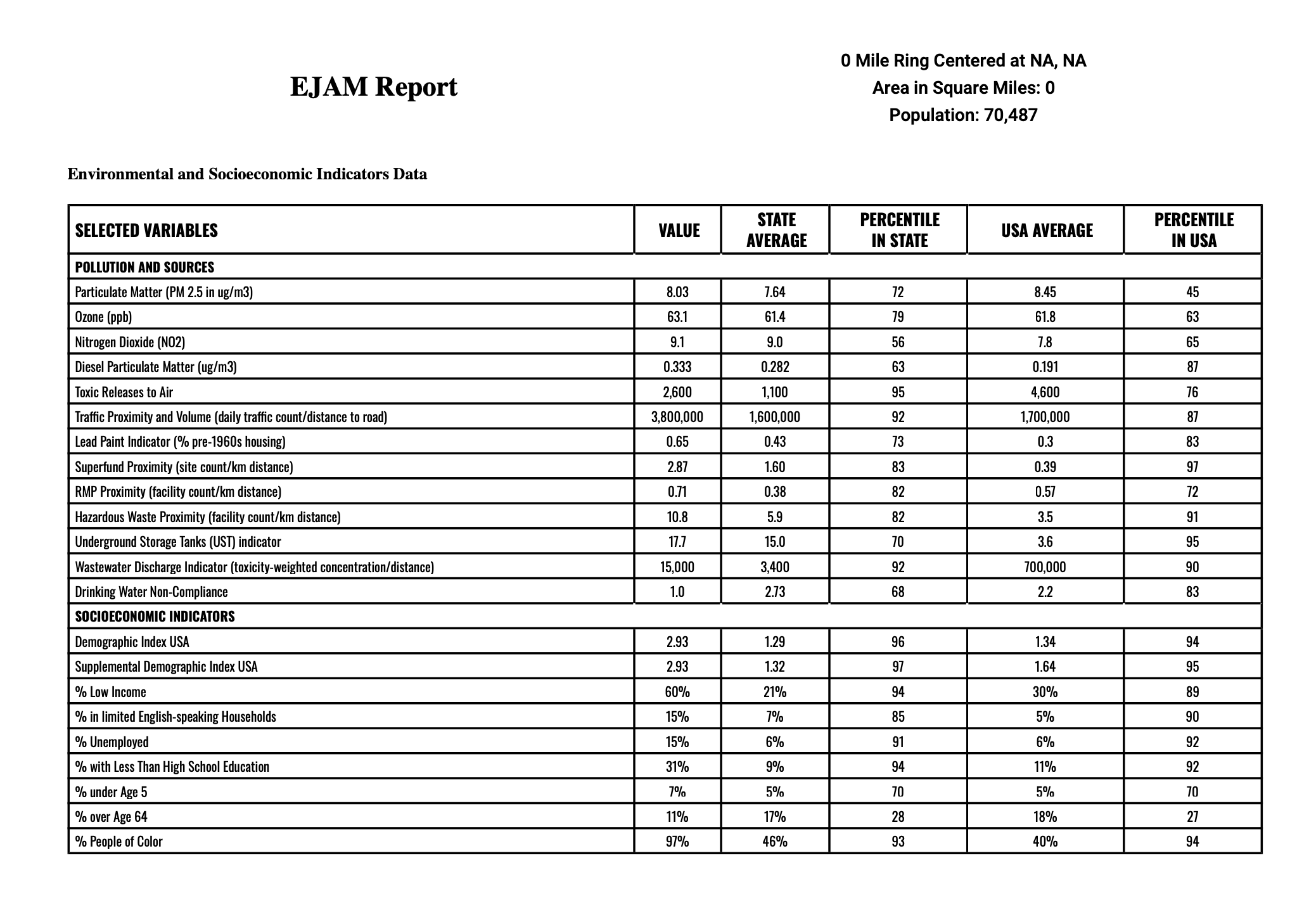

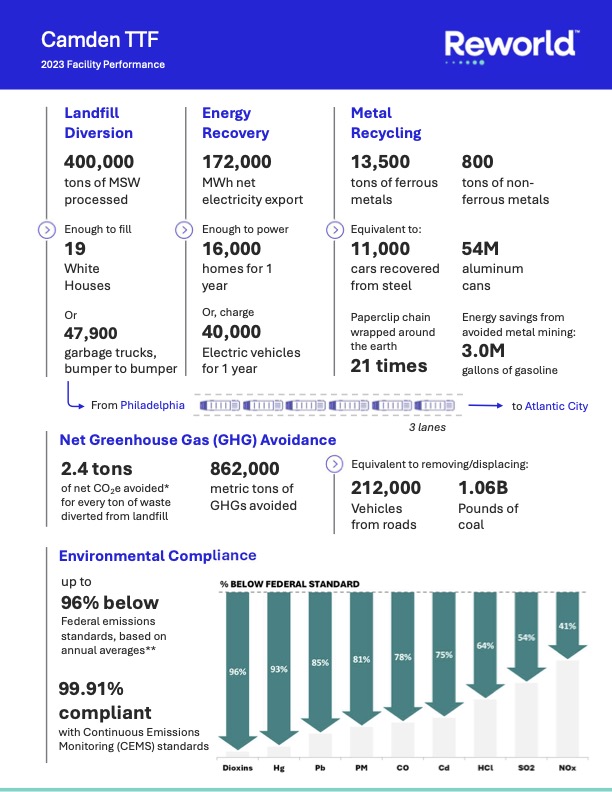

This is a recent performance sheet from 2023 by the company that runs the garbage incinerator in Camden. Although this data is from 2023 and my topic takes place in the 1980’s-early 90’s, I want to use this as evidence that supports the incinerator’s usage. Most of my sources I’ve looked at are from the community’s perspective claiming the incinerator is bad. This is coming from a corporation’s perspective and provides us with positive stats about the incinerator; the data insists they are following guidelines to protect the environment.

Primary Source Analysis: Camden TTF

This source is a data performance sheet from 2023 by Reworld, the corporation that runs the garbage incinerator in Camden. It shows that they are prioritizing environmental compliance by following the EPA’s national emission guidelines . It is my perspective that the data is suspicious, and many citizens from Camden would agree that this does not apply to what’s going on in the city. What the data is not showing is the amount of people getting sick from the emissions. My argument is that Reworld is underreporting the amount of emissions being released into the environment in order to avoid lawsuits. Reworld is trying to play the good guy in this situation, they’ll do anything to avoid the truth.

My first evidence is Reworld showing how much energy was saved in waste- providing stats of landfill diversion, energy recovery, and metal recycling. Although the incinerator may help produce energy into American homes, we can not deny that toxins are still being produced in the process. The second evidence claims that 2.4 tons of net CO2 is avoided for every ton of waste diverted from landfill and 862,000 metric tons of Net Greenhouse Gas avoided. The data never mentions landfills being 100% clean air, indicating there is still carbon dioxide within the zone. This is an area of low income minorities, and they are being affected with their respiratory health. The last evidence is Reworld claiming their environmental compliance up to 96% below Federal emissions standards, based on annual averages. This makes them seem like they’re being compliant with guidelines. In reality, the community is suffering through social and health problems. Reworld is not advocating for better waste management. Reworld has political and economical advantages over Camden, which is hurting the community. The community is suffering because Reworld is not being honest in their report. When the community has held protests to shut down the incinerator since it first opened, you know there needs to be change.

Secondary Sources:

1. Sicotte, Diane. “Saving Ourselves by Acting Locally: The Historical Progression of Grassroots Environmental Justice Activism in the Philadelphia Area, 1981–2001.” In Nature’s Entrepot: Philadelphia’s Urban Sphere and Its Environmental Thresholds, edited by Brian C. Black and Michael J. Chiarappa, 231–49. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.11249276.14.

This chapter discusses the Incinerator battles that took place in the late 1970s to the 1980s. I like this book chapter because it focuses on the landfill crisis- many areas were running out of space for trash in the Philadelphia region including Camden; they needed a solution, and that solution was to build incinerators. I also like this chapter from the book because it provides the aspects from the community, not like the idea of an incinerator in the neighborhood. It shows how environmental activists protested the proposed incinerator. This source provides the name of activist groups such as South Camden Action Team (SCAT) and Citizens against Trash to Steam (CATS); it helps me understand who was involved- the people being affected.

2. SICOTTE, DIANE. “Intersectionality and Environmental Inequality in the Philadelphia Region.” In From Workshop to Waste Magnet: Environmental Inequality in the Philadelphia Region, 139–56. Rutgers University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1gn69sc.13.

This book chapter explains how certain races, class and gender are targets for environmental inequality living within the Philadelphia metropolitan area such as Camden. I like this source because it goes hand in hand with my argument. How certain groups of people are taking advantage of, and this source can help push my argument further. For example, what certain factors make a person a target in these situations.

3. SICOTTE, DIANE. “The Rise of Industrial Philadelphia.” In From Workshop to Waste Magnet: Environmental Inequality in the Philadelphia Region, 56–83. Rutgers University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1gn69sc.10.

This book, specifically this chapter, talks about Camden once being a thriving industrial city in the first half of the 20th century along with Philadelphia, both cities big for manufacturing. I like this book chapter because I can use it to compare and contrast the economic differences between the first and second of the 20th century in Camden. How people were living, what type of opportunities they had, and what the neighborhoods were like.

4. Gillette, Howard. “Camden Transformed.” In Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City, 39–62. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhqkq.7.

This book chapter does a good job explaining the transition in Camden from a white to a predominantly black city. I like this source because it provides a U.S. census report of jobs and population in Camden from 1940-82. Looking at the data, by the 1970s there were fewer jobs and less people living in the city. Looking at the data, I can assume Camden was going through a time of deindustrialization.I can use this information to show that Camden suffered an economic decline. Using the data, I can elaborate on the economic decline influencing Camden’s desire to desperately save themselves by building an incinerator to create some type of financial stability, a type of income.

5. Hurley, Andrew. “From Factory Town to Metropolitan Junkyard: Postindustrial Transitions on the Urban Periphery.” Environmental History 21, no. 1 (2016): 3–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24691539.

This article does an excellent job showing the history of deindustrialization with places such as Camden. This source provides information on how cities managed to recover from deindustrialization, using waste matter to create economic growth. I can use this source to show how corporations and politicians used garbage related facilities for political gain in certain cities such as Camden allowing poverty to flourish. I think this source is great for me to use because it explains how socioeconomic factors correlate with environmental hazards, this ties up with my argument. I want to raise awareness about the inequality in low income neighborhoods.

Image Analysis:

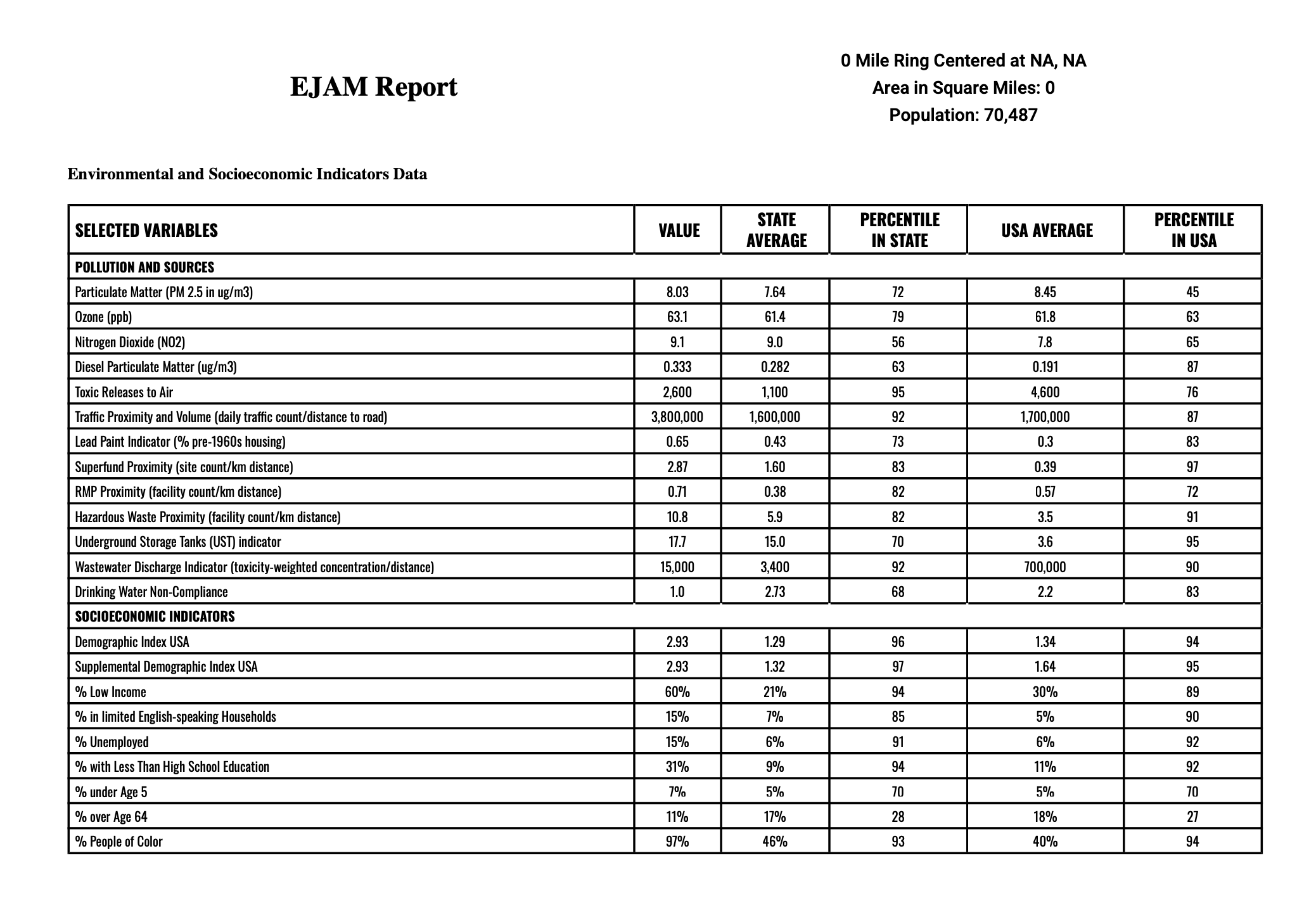

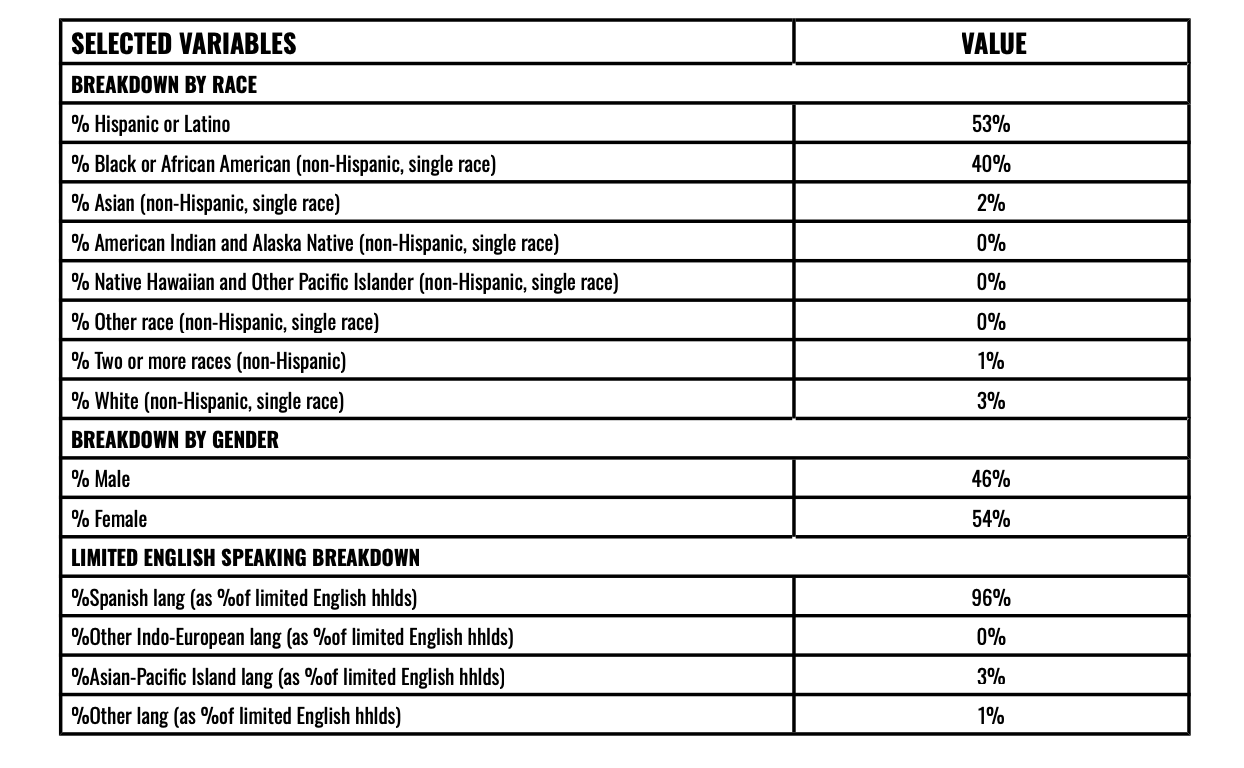

Data Analysis:

The following data comes from the Environmental Justice Screening. It is a 2023 data report on the city of Camden, reporting on pollution and sources, and socioeconomic indicators. I plan to use this information to explain the social issues that impact local residents of Camden, New Jersey. With a big focus on the Camden Incinerator, it’s been a controversy since the very start of its existence. The people of Camden have never been on board with having a garbage incinerator so close to their home; they have known about the incinerator’s environmental hazards. They tried to address the issue with their local government, but the city has other priorities- it does not include shutting down the incinerator.

Oral Interviews:

Video Story: