Looking a Gift Horse in the Mouth: Artists, A Sick Building, and Gentrification in Newark

by Colleen G. O’Neal

Site Description:

Artists and grassroots organizations play a pivotal role in the development of any city, often functioning with little to no resources, but providing great service to a city’s inhabitants. With few resources, but needing accessibility to their communities, these groups can become pawns to larger corporate interests looking to hedge their bets on real estate ventures.

In 2019 Jerry Gant’s last piece of artwork was removed from 31 Central, and so marked the end of an era in Newark’s Artist Community. 31 Central is located on the corner of Central Ave. and Halsey St. in downtown Newark, NJ. It was once home to a plethora of diverse businesses and organizations throughout the twentieth century, but by the end of the century the building was becoming sick, ultimately falling into a dilapidated state. From the 1990s until it’s closing, the building was rented to artists as well as two grassroots organizations: YouthBuild Newark, and the Newark LGBTQ Center, all while being observably infected by mold, leaky ceilings, and peeling paint. The inside was falling apart, but directly outside of 31 Central’s walls, Newark was being built up with glass towers and skyrocketing rents. Both 31 and the aforementioned Prudential Tower are located in downtown Newark, and both are owned by Prudential (31 is listed under subsidiary Cottage Street Orbit Acquisition, LLC).

I want to understand how the artists, grassroots organizations, and Prudential were affected by the renting of spaces that were in undeniable states of disrepair in conjunction with the perceived value of the neighborhood directly outside the building. Understanding who benefits and who pays the price, be it financial or health related, in this complicated relationship of ownership and community, aims to provide an opportunity in discovering new channels of healthy and symbiotic collaboration. It is important to the integrity of any city to maintain niche communities which serve them, even when that service is difficult to quantify in Capitalist terms.

Final Report:

Introduction: The Anxious Object

“An anxious object is an object that is anxious to express itself. It can’t hide its own history, its own intent in the world, its past, present, future, are all on the surface and in the air around it, like an aura.”

– Willie Cole[1]

The anxious object acknowledged in this paper is the empty hulking mass of a building located at the corner of Central Ave and Halsey St in downtown Newark, NJ. Astutely dubbed “31 Central” by the artists that once inhabited it, this anxious object has an aura and history that drew me to it once as an artists space. Now vacant, the great magnetism of this object has pulled me in once again to dig into the significance of the space before it is demolished for yet another luxury apartment complex. Cole references the “anxious object” akin to a battery, which when harnessed properly can bring the work to life. This essay is an attempt to harness the energy of 31 Central and center it within a study of the multifaceted, delicate, and dangerous relationships artists and their artwork have with local government, developers, physical spaces, and communities they work with and in.

31 Central has physically engaged the city of Newark for close to a century. The energy of the building shifted over time, sometimes casting a cold shadow on the street outside, other times creating enclaves for those working within. From the 1980s until it became vacant in 2019, the building was rented to artists while being observably infected by mold, leaky ceilings, peeling paint, and exposed electrical wires. The artists engaged directly with the sick building, finding refuge in a strong sense of community that bloomed among cheap rents, a centralized location, and the sense of autonomy. Contrasted against a backdrop of rapid growth and revitalization in the neighborhood, the artists at 31 Central provide a unique perspective into the inner and outer workings of gentrification as it unfolds.

I began my research investigating the working conditions of artists at 31 Central, and quickly realized that the site was only one piece of the much larger issue of gentrification in the area. I am presenting this research with an undeniable bias, since I have been part of the artists community in Newark since the mid-2000s. I have also worked with the local government and developers in the area on projects. I wanted to understand the direct relationship between the geographical sites of artists studios, the physical conditions of these sites, and redevelopment incentives. If this relationship was a calculated one, could the artists be used as tools for measuring the return on tax dollars used for revitalization efforts? By presenting multiple perspectives, isolated experiences can become part of the collective memory. Finding points of intersection with others can lead to a more egalitarian city plan, opposed to the restrictive and destructive brand of gentrification that is currently being employed.

Gentrification is not a new phenomenon, it has been studied and written about for decades. Artists are not new to the process, but there is less written on this particular point of intersection. David B. Cole’s work from the 1980s is a resource I relied heavily on to make the connections between artists and gentrification as they began leaving New York City in search of cheaper space in New Jersey.[2] The fate of Newark was not resolved, my research expands on the years after B. Cole. Kathe Newman and Kristyn Scorsone have both written more contemporary histories of gentrification, specifically in Newark. Newman focuses on community-based resistance to gentrification from a public housing perspective, while Scorsone presents the resistance in a community of Black lesbian entrepreneurs.[3] My research, while building off of theirs, provides a perspective from the artists who overlap with both of the aforementioned studies, as well as to highlight the dark underbelly of tax abatements in New Jersey. Art has been written about for thousands of years, my inclusion of the works and analysis is an attempt to illuminate points of intersection between art and environmental justice.

The story of 31 Central and the artists that worked there is an intersectional history of art and politics, gentrification, and displacement. Beginning with the inseparable nature of the artists and their environment, the paper briefly expands on the history of the arts in Newark before the PATH Train brought artists from New York. Key language for understanding the long-term costs of gentrification is incorporated from government documents to draw attention to the connection between tax abatement programs and funding for public schools. Additional attention is given to redevelopment practices and the condition of the buildings artists agree to inhabit through a case study of 31 Central, incorporating artists interviews and visual documentation. By investigating the artists’ acknowledgement of ongoing gentrification, I uncovered a heated public discussion on the topic on a local news site. Incorporating non-artist experiences from scholarly journals with the Mayor’s optimistic plan presented in a vlog, the paper concludes with more questions than answers. Artwork is used throughout to illuminate ideas, and create opportunity for non-linear thinking surrounding the issues.

Dirty Old Town: Freedom in Forgotten Architecture [4]

Artists don’t occupy space, they consume it, and it consumes them. There is a constant dialogue between life and art that can be found in finalized works, hanging like carcasses on museum walls, but what often remains hidden are the lungs that breathe life into the work. If the breath is the artist’s process of creation, the lungs are the environment in which the work is being created. Renowned artists and poet Patti Smith described the loft apartment on 24 Bond St, north of Houston St, or NoHO, in Manhattan that her artistic other, photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, was moving into as both a live and work space. Smith, began her chapter “Separate Ways Together” in Just Kids, screaming quietly in a way that only poets can, about the important relationship between artists and their environment, including community and architecture, as well as the desire for artists to make a space their own. The need for an artists community is clearly expressed in the first line, “We went our separate ways, but within walking distance of one another.”[5]

The punk poet laureate embraced the architecture on Bond St. by meticulously immortalizing “cobblestone side street with garages, post-Civil War architecture, and small warehouses”in the first paragraph.[6] The impact of the interaction between body and environment is given great weight as it is recounted 40 years later. Smith eternalizes the process of enveloping and being enveloped by the surrounding environment as she recounts the area “was now coming to life, as these industrial streets will, when pioneer artists scrub, clear out, and scrape the years from wide windows and let in the light.”[7] A community of “pioneer artists” had shaped the revitalization of the area, and begun the process of breathing life back into the lungs of the architecture. The space is not glossed over as just another apartment or room in Smith’s description, but as part of the artist “Much of the original brick was concealed with moldy drywall, which he removed. Robert cleaned and covered the brick with several layers of white paint and set it up, part studio, part installation, all his.”[8]

Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph, Patti Smith, is a black and white square photograph of a nude Patti Smith sitting upright on the floor in a fetal-esque posture just below center of the frame, with her dominant eye perfectly in line with the vertical axis.[9] It was taken in 1976 in the studio Smith relished in Just Kids. The portrait incorporates the body seamlessly into the architecture, the two bonded forever in this moment of time. The top left of the frame incorporates part of the large industrial windows which provide the natural lighting for the photograph. Pipes, described as erratic with eruptions of steam, push and pull between the foreground and background, broken only by the hands and arms of Smith.[10] The floorboards mimic the parallel horizon, encapsulating the figure’s organic shape within the hard lines of the architecture. Sitting close to the pipes gave her the ability to reach them, and as she held the pipes, she held the architecture of the building in a dual embrace of artist and space. Smith and Mapplethorpe simultaneously engaged in the creation process, the breathed air into the lungs of 24 Bond.

The image of Smith accompanied by her text illustrates the importance of architecture as a necessary element in an artist’s life and work. 24 Bond was built in 1893 in the Renaissance Revival architectural style, perceivable by its indented cornice, brick façade, and row of arched windows.[11] The architecture is part of a venerated symbiotic relationship with the artist it consumes. Not all buildings are the same, and therefore do not suit all endeavors equally. The artists relationship with 24 Bond was well suited as large windows and open loft space did not restrict movement, Mapplethorpe was free to rearrange, install and deinstall, work, party, and conduct photography sessions. The space was permeable and unrestrictive not only to human bodies, but to the movement of light and air, energy, and pollution.

Rapidly rising rents in Manhattan in the 1960s and 1970s created an exodus of artists who did not receive the same philanthropic support and access to space as Mapplethorpe.[12] Seeking large, cheap, well-lit space, artists turned their sights on Brooklyn, Hoboken, Jersey City and Newark.[13] Aiding developers and local government in the gentrification process, artists were “romanticized because of their willingness to live in run-down areas with old factories and warehouses or to break racial and ethnic barriers…”[14] Along with the increasing cost of living in New York, there were two other major factors in artists relocating to Newark. First was the acquisition of the H&M Railroad by the Port Authority, commencing with the entrance of the first four railcars into commission in 1965.[15] The newly minted PATH Train made it quick and easy for artists to access the vibrant and international art scene in New York from their cheaper New Jersey studios. The second major factor in the artists relocation was the desire of local governments in New York’s satellite cities to lure investors through financial incentives in redevelopment projects. Artists have been incorporated in revitalization plans as far back as the 1960s, with success in Dallas, New York and Los Angeles.[16]

Pioneers of the PATH Meet Newark’s Established Artist Community

Artists moved geographically westward from New York following the PATH Train line, taking up spaces first in Hoboken, followed by Jersey City, and finally Newark. With local economies gasping for economic stimulus and blighted properties abound, local governments and real estate developers worked in lockstep to secure artists in the often vacant spaces.[17] Labeling properties as “blighted” was the key that allowed local municipalities to offer ethically questionable tax incentives to redevelopers in the area.[18]

Artists found cheap rents in Hoboken until their industrial lofts became coveted by the housing market exploding westward from New York City. Increased rents forced local communities and artists out of their spaces.[19] Some artists who refused to leave their spaces were met with settlement funds, as much as $20,000 each was paid in one instance to make way for luxury apartments.[20] Localized community action helped to retain 25% of space for affordable housing awarded through the Community Development Agency in Hoboken.[21] As artists migrated further from New York along the PATH Train line, their next stop was Jersey City.

The developers and local government had specific intentions in their use of artists in the gentrification plans in Jersey City by creating special live and work zoning for artists through the creation of the River View Arts District.[22] The main issue with this district is that it was not previously deemed blighted. Special concessions were made for redeveloping the property, prized for its proximity to New York City and beautiful city skyline views. The local residents in the area were struggling with high poverty and unemployment rates, limiting their agency in matters of redevelopment. 36% of the population identified as Hispanic at the time, with half of this population identifying as Puerto Rican.[23] Attacks against these communities through gentrification seemed overwhelmingly intentional, especially after a wave of targeted arson forced these communities out of Hoboken in the 1970s.[24] Artists were essential in the Jersey City plan to displace underserved and under-represented populations, making way for the influx of white middle-class residents to the area.[25] Working-class citizens began to see artists as a threat and the first sign of gentrification. Often artists have not been explicitly aware of their role in the process, and will support local businesses while working with the local community against rapid gentrification.[26]

The pioneers of the PATH in no way discovered or rediscovered any part of Newark, but were met instead with a community of artists, and local art spaces. The most established gallery in Newark at the time was City Without Walls Gallery, opened in 1975, it served as a beacon to artists leaving New York.[27] With a convenient downtown location, the gallery provided community and collaboration to local artists through collective exhibitions.[28] Newark was also home to the Newark Museum, the Paul Robeson Gallery at Rutgers, the Aard Studio Gallery, run by local artist Gladys Grauer in the South Ward, and The Works Gallery, run by the local artist Willie Cole out of an old factory in the Ironbound.[29]

Artists were attracted to the Ironbound section of Newark due to the proximity of the PATH, and its stock of old factory and warehouse buildings just a short walk from the vibrant and international scene on Ferry St. Available raw spaces were converted into artists living and working space. As the revitalization process in Newark took hold, artists searched the city with real estate agents to find suitable spaces they were willing to fix up and work in. Not completely aware of their implication in the process that was unfolding, artists contributed to the stomach churning practice of municipal tax abatements in New Jersey.

Tax abatements in New Jersey are the equivalent of biting into a beautiful apple that is rotten and mealy to its core. Abatements are crucial in understanding information that lurks in the shadows of urban renewal. As defined in a report by created under New Jersey State Comptroller A. Matthew Boxer, tax abatements are “reductions of or exemptions from taxes in the name of economic and community development… granted typically to businesses and developers to encourage them to make improvements to property or to locate a project in a distressed or blighted area.”[30] The term blight is subjective and can easily be perverted, leaving the future of entire neighborhoods to the whims of a developer, and representing the mealy part of the apple. The complete internal rot of the apple is represented in the act of stripping public schools of funding within the fine print of the tax abatement program in New Jersey. The abatements literally rob schools of their funding, and are therefore directly cheating the tax payers, neighborhoods, communities, and the students out of their future.

There are two types of abatements, long term and short term. The short term abatements last five years. If a developer meets specific criteria, they are given either a five year reduced property tax bill, or make a one time payment to the municipality in lieu of taxes called a PILOT (payment in lieu of taxes). The criteria set by the local municipality is the only discretionary practice used in granting short-term abatements. Long-term abatements are allotted for large areas of redevelopment and can last anywhere between 30 – 35 years, providing a tax exemption for the specified length of time, but requiring an initial PILOT to the local municipality.[31]

The utterly preposterous part of the process is the involvement of the local public school systems. The PILOTs are paid to the municipality in lieu of taxes on a property that will eventually increase in value due to gentrification. The funds obtained by the municipality through a PILOT do not get disbursed at an equivalent ratio to taxes disbursed to schools. Instead, the schools get nothing, zero, completely disregarded in the PILOT.[32] Cutting the schools out of a huge portion of their income every year, even as the property values increase, is degrading at every level. It seems counterintuitive to levy an inverse tax against schools for 30 – 35 years of corporate gain. Comptroller Boxer expresses grave concern in the study stating “Municipalities often fail to use abatements to bring in the type of redevelopment that would address community needs or bring appropriate improvement.”[33] If the development is not created in response to community needs, but the community is paying for it, how is this improvement? Although a great artist like Willie Cole came out of the Newark school system and ultimately became successful, this barely regulated program of reverse Robin-hooding is neither fair nor sustainable.

Newark has a high rate of the population living below the poverty line, as well as large Hispanic and Black populations.[34] Using Jersey City’s plan for the River View Arts District as a bellwether, the struggle for equitable community growth is a logical concern for the future of Newark. Without a clear return on the municipal investments made through tax abatements, a toxic cycle is created to keep the municipal coffers full while those most in need of protection, specifically low-income public school students in Newark, pay the price through the slow violence of tax abatements.[35] Two generations in a row can be forced to shoulder the burden of disinvested education systems in Newark, not fitting for the vocabulary designated to this process such as “revitalization,” “reinvestment,” and “smart growth.”

The Oxymoron of Artists in Offices

The real estate market followed the path of the artists, turning jewelry and shoe shine factories in the Ironbound into posh apartments marketed to the white middle class, just as Hoboken did in the 1980s.[36] Although trendy, the converted factories posed a variety of problems for “non-artist” tenants. The spaces are notably difficult to heat and cool, and therefore inefficient consumption of resources. Issues such as needing to call a commercial roofer, or filling gaping holes in factory floors, becomes costly and problematic for renters.[37] Needless to say these pricey problems are considered insignificant for high income brackets in exchange for a hip address in a chic artist-style loft. The increased rents pushed many artists from the Ironbound in search for cheaper space within the city.

As developers continue their success through increased profits from luxury rentals and tax abatements, they have become more tactical in their approach of increasing their property values. As artists looked for large cheap and empty spaces, they were guided to old office buildings and defunct retail space downtown. The spaces were different from the factories, they were less stripped down, and contained more materials like carpets, tiles, drywall, wires and vents, and more insulation. The office buildings were built in a different style, a style of more. Many of the buildings, like 31 Central, lie to the west of Penn Station and the Ironbound, but still in walking distance.

In the gap time between purchasing an old building and redeveloping it, artists could be used to safeguard the investment. Upkeep and further investment in the property during thew gap time would be minimized by the artists who generally don’t complain and want to be left alone.[38] I imagine this “gap time” is how 31 Central became an artists space in Newark. Built in the early twentieth century and once used for retail and offices, artists began renting studio spaces in the building in the 1980s, the exact year remaining elusive.[39] During this time the building was falling into disrepair and putting the artists health at risk. Instead of redeveloping the existing artist studios into inefficient luxury apartments as previously done with factory spaces, the building would be demolished. The artists played a role in the creating the community vibe on Halsey St, and attracted “outsiders” to the area. Once the artists were no longer needed, they were removed.[40] 31 Central is still standing but vacant, and it will soon be demolished. The artists were reported to have been surprised upon learning the site will be redeveloped as a “10-story building with 71 units, retail space, and commercial space.”[41]

As noted in the works of Smith, Mapplethorpe, and Cole, the relationship between artist and environment is inseparable, but at 31 Central it was also toxic. What artists have expressed time and time again is that they need autonomy within the sacred space of the studio.[42] There is an unspoken agreement between artist tenants and landlords; neither wants to be bothered by the other. The artists want autonomy, and the owners, especially in instances when demolition is planned, do not want to spend any money. The artists get cheap space, and the developers get peace of mind that the neighborhood will slowly improve because of the artists presence over time. This arrangement works for all parties, so long as the proverb “don’t look a gift horse in the mouth” is strictly adhered to.

I propose to look that gift horse straight in the mouth. At 31 Central artists were granted general autonomy and a true family of artists bloomed through their support of one another.[43] They had a centralized location close to the PATH Train and other artists in the area. A short walk from universities and the Museum, rent was cheap and space was plentiful. Landlords didn’t need to mind the building much due to the constant comings and goings of artists on non-conforming schedules. Bars, family restaurants, and bodegas could rely on the artists who were otherwise situated in a food desert. In the late 1990s a group of young artists were drawn to 31 by their professor, who was an artists renting a studio there.[44] The students followed suit, renting a large shared studio space on the second floor. Oliwa and Craig both recount the state of destruction at the time, but put in the necessary sweat-equity to clean up the space, Craig noting the owner at the time even repaired the windows attributed to some of the interior damage.[45] Craig details life as an artist at 31 Central in the oral interview below.

As the building deteriorated over time, the artists were aware of their environment. When asked to “describe building management” artists responded with laughs, more laughs, and optimistic irritation “the maintenance of the building is not applicable, it’s null and void, it’s fucked up, its deteriorating inside… but something about not being too comfortable often can inform and inspire great art.”[46] The relationship between the artist, environment, and developers is a complicated one. Other artists responded positively, noting the feelings of safety within the artists community and appreciating the building owners leniency and support.[47] Another artist expressed that the low rent and downtown location combined with being left alone by the landlord was an even exchange.[48] The unwritten rule between artists and landlord is “silence is golden.” If an artist perceives the relationship to be fair, then there is nothing to argue. If the artist feels exploited and makes noise though, they run the risk of losing access to their space as well as potential spaces in the future.

To claim 31 Central as a Sick Building, but without being able to physically test the site, I have relied on interviews, images, and studies. As the building was slowly deteriorating, Hurricane Sandy delivered the fatal blow in 2012 by causing damage to the roof. The leaky roof was a major concern for tenants and warranted a call to the landlord for repair. Without ever fully or properly repairing the roof, the tenants were left to occupy a building that crumbling from water damage.[49] The building was sick, and spreading its toxins slowly and silently to the remaining tenants. A clinical study of the negative effects to health after exposure to water damaged buildings, or WBDs substantiates the claim of direct association.[50] As the water damage spread, so did a host of potentially harmful and airborne bacteria and mold spores. What was the personal toll attributed to each artist in the building? Did the air quality affect their ability to create work? Were there long-term health effects that were caused due to their relationship with the environment?

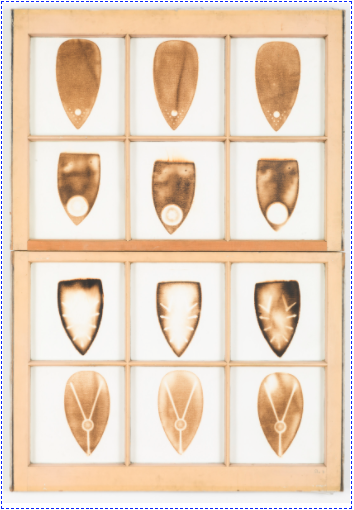

Left: NPR examples. Right: Images from 31 Central, 2016.

In addition to the health issues created by unresolved water damage, it can be concluded through a brief visual analysis that the tenants also faced toxins from lead paint, easy to identify by its signature chipping and peeling. Above are examples of lead paint, the images on the left are examples of lead paint from a school building.[51] The examples on the right are from photographs I took at 31 Central in 2016. Lead paint primarily poses a risk when it breaks down into a dust form and can be breathed into the lungs, potentially damaging the brain, nervous system, and reproductive system.[52]

The environment inside of 31 Central didn’t only affect the health of the artists, but also the work they were creating. Hawak/hold (8.7832, -124.5085) is a larger than life charcoal and pastel rendering of a churning sea shown from an aerial perspective completed in 2019 by artist Katrina Bello. The drawing represents a point of intersection between the environmental decay at 31 Central, and continued environmental shifts on a global scale through the intentional use of duality, process, and form. By collaborating with the physical state of the building in her studio at 31 Central, Bello offers a direct yet subtle contextualization of environment through the use of title, and the process of mark making. Condensing 8,500 miles of distance between Philippines and Newark into one seascape, Bello is creating a heightened connective awareness for the viewer to explore within the details. Bello’s intention was not to create a “beautiful piece of art.” The artist incorporated clues into the work that beg for deeper investigation.

©Katrina Bello

A striking example of duality within the work is presented in the title Hawak/hold which is a repetition of the same word in different languages, as Bello draws inspiration from her personal migration stories from Mindanao, Philippines.[53] “Hawak” translated from Filipino to English means “to hold,” and other close variations of “hold.” This repetition in the title requires the viewer to reconsider the image not as just a standard representation of water, but also bearing another meaning. The act of holding water is in itself a duality, as two entities are necessary, something to hold and something to be held. The repetition of the duality within the title indicates the artist is paying close attention to the details within the piece itself, as well as in the larger context of global discourse. The second half of the title, (8.7832, -124.5085), seems to represent geographical coordinates. When searched on a map, the coordinates denote a remote and truly indiscernible location within the Pacific Ocean, halfway between Newark and Mindanao, and signaling a link between the two. The artist is guiding the viewer and pointing to the locations being contextualized within the work by recreating the ocean that both separates and joins them, even when remaining visually elusive.

Bello is sly in the way she incorporates pertinent information into her artwork, concealing it within the depths of the shadows, leaving only faint clues of her process. The first layer created by Bello in Hawak/hold (8.7832, -124.5085) bears great significance, as it was not created by the artist alone. Bello taped a large void of blank paper to her studio wall, rubbed charcoal on the paper’s surface, and the texture of the wall appeared resulting in the first layer being created, a process commonly referred to as frottage. This first mark was made not by the artist alone, but as a collaboration between the artist and the environment, a continuation of the long tradition of dual embrace. As the 31 Central building slowly decayed, it provided a myriad of textures for frottage. The studio wall would have certainly been less useful if the building had been properly maintained. Bello draws mainly from photographs, as she did with this work, but allows the materials and environment to inform without strict demands, allowing her to literally draw her studio into the sea by incorporating the texture of the wall through with her rubbings. The final image is determined by the marks in the first layer as they are built upon and layered over in the process which is determined by the physicality of the building, dictating shape and form and directly contributing to the topographical seascape. The decaying building becomes part of the sea that is a representation of vast expanses and globalized environmental degradation.

Forms and spatial relationships within the details of the work are direct results from the interaction of the building and the act of mark making, culminating in the final seascape. When referring to a seascape the image of an island retreat, with beautiful glimmering waves, peaceful shores, and possibly a setting sun will be conjured. Hawak/hold (8.7832, -124.5085) is a different type of seascape. The larger than life size of the work altogether envelops the viewer, at 5’ x 8’6.” The aerial perspective of the piece displayed vertically challenges the normative gaze, creating an uneasiness in viewing and suggesting closer examination. The overwhelming image of a deep and churning ocean is not intended to ease or welcome, the sea is depicted as foaming and foreboding. The motion within the waves attracts and repels simultaneously as the eye is pulled into the depth of the shadows and then forcefully pushed back to the surface within the formation of highlights in frothy film rolling over the water.

The color palette is limited to white, reddish brown, deep teal blue, and black. The limitation creates a realistic feeling of water, as the colors are also used to represent the agitation in the sea. The absence of a placid and unbroken blue sea indicates the dramatic and chaotic motion in the underlying flow of water. The sea is an ideogram representing both the microcosm and macrocosm of environmental damage from an artists studio in 31 Central to the coastal changes in Mindanao.

This seascape is at first seemingly incongruent with 31 Central, but through the close analysis of duality, process, and form, deeper connections are revealed. Similar but different to Cole’s reference to the “anxious object,” Bello employs a technique of embedding the energy of the building through her mark making process. The building’s energy, anxious to express itself, was harnessed by Bello. I spoke in depth with her about the work in 2018 while it was being created in the studio. She had held at 31 since 2012, and had recently been advised by the building’s management that she had to leave. Bello told me she felt like archiving the building and the time she spent there, so she began Hawak/hold (8.7832, -124.5085) as a way to achieve this goal and pay homage to the space.[54] With the dual embrace inescapable, Bello drew herself into the final chapter of 31’s history.

“Someday This Will All Be Condos”

Blight, gentrification, and environmental injustice came to a gnarly head at 31 in 2019 when the last piece of artwork was removed from 31 Central marking the end of an era in Newark’s artistic history. I asked Lowell Craig in 2020 if he thought artists had a role to play in gentrification, his immediate response was yes. After sharing a laugh he went on: “I mean if you think about what gentrification means, right, it means changing the landscape usually the landscape is… ahh… not so pleasant, and uh you know I feel like artists, artists and bars are basically the first thing, uh… the first tool in like a developers tool kit. Bring in artists and bars and the neighborhood seems like: Hey! You know… there’s something going on here! So yeah, I feel like artists are the point of the spear in certain situations, if gentrification is the goal.”[55]

It’s important to acknowledge that artists are somewhat aware of their contributions to gentrification. In 2007 the art/rock group American Watercolor Movement presented their work at Gallery Aferro. As a regular to the gallery, I have seen hundreds of promotional postcards, but the one for this performance and installation struck me. Centered two-thirds of the way down on the antiqued white card stock, the date and address were printed in bold black text. Below the street address, but above the large text reading “Newark,” and perfectly centered between the goalposts of “N” and “k,” nestled within parenthesis, was the blatant observation: “(Someday This Will All Be Condos).” The future of Newark was plainly seen in 2007 by a regional band of artists and musicians who had recently witnessed the loss of iconic art and music spaces in Jersey City due to gentrification.[56] Gallery Aferro still maintains the same gallery and studio spaces on Market St., a short walk from 31 Central, but their long-term future at the site is only as secure as their relationship with the developers holding the deed to the building.

Gallery Aferro

Gentrification comes in many varieties, and is met with a spectrum of opinions from local community members ranging for awful to fantastic. One place to find these opinions is in the comment sections of local online news sites. An article addressing public agency as a way to create historic archives of places like Newark’s West Ward via Instagram encouraged wide debate on the tools and scope of gentrification. The unadulterated public opinion was heavily focused on the perceived effect race and class had on gentrification, specifically along the line of the PATH Train. One person recognized that as neighborhoods are revitalized, larger and much needed businesses become attracted to the area, the example given was a CVS. Brands like CVS not only provide jobs and training within a local economy, but also provide a place to purchase food, medicine, and basic household items. Large pharmacies often offer free flu shots, and on site patient care. In low income neighborhoods with less access to automobiles, a business like CVS in walking distance to the home is a precious commodity. Other comments were in disagreement, citing inhumane treatment and displacement of marginalized racial groups, specifically of Puerto Rican descent, who had historically displaced from their homes through the means of arson. The artists are never mentioned in the wildly open and sometimes racist comments below the article. I am unsure if this is because the commentators are not aware of the artists role, or don’t consider them to be an important factor in the redevelopment of “blighted” areas. Another missing element from the heated exchange were tax abatements. Although the free spar wielded attacks against renters for not having the ability to pay higher rents as property values increased, the redevelopers were mainly viewed as “just doing their jobs.”[57]

The artists and local communities in and around Newark are aware of gentrification, but the definition of gentrification seems slightly different to everyone. Newman defines gentrification as “a product of uneven development, economic restructuring, and cultural preferences shaped by politics and public policy.”[58] In a 2004 journal article she looks at community agency in downtown Newark’s Brick Towers as locals banded together in an attempt to save their building and community from destruction and their own inevitable displacement. The area was highly coveted by redevelopers and eventually deemed “functionally obsolete,” conveniently fitting into a loose interpretation of blight. The communities’ effort to save their homes was Herculean. They banded together to raise funds in order to fix the decay resulting from years of negligence by the landlords. They hired lawyers, fought in court, and even developed a plan to save the federal government $12 million dollars allocated to the demolition of the property.[59] In the end the community lost and the buildings were razed for a new housing development, displacing original residents in the process. One key aspect of the story that stuck out was the willingness of the community to fix up the buildings in lieu of being displaced. When the buildings were taken over by the Newark Housing Authority, conditions in the buildings deteriorated further. “Local advocates interpret this as a mix of ineptitude combined with intentionally encouraging residents to leave.”[60] The slow violence of deterioration that helped to force out tenants looked almost identical to the deterioration at 31 Central.[61]

Another community dramatically affected by gentrification in Newark are queer Black women.[62] Socially marginalized queer Black women in Newark have created a strong community through entrepreneurial endeavors and grass-roots organizations. The businesses and organizations can be the backbone of a community, but in a geographical context can also encourage gentrification, ultimately leading to their own displacement. The queer Black women in Scorsone’s study were responsible in creating safe spaces for LGBTQ youth and adults in Newark.[63] The Newark LGBTQ Community Center opened in 2013 at 11 Halsey St. in downtown Newark.[64] The address given is based on the location of the front door, facing Halsey St., at the intersection of Central Ave. The LGBTQ center was physically located in the same exact building as the artists of 31 Central. Opening one year after Hurricane Sandy, I wonder if the group knew there was a neglected hole in the roof, and that the building was slowly filling with mold and deteriorating lead paint particles.

The LGBTQ Community Center, as well as the artists studios, had a direct effect on the surrounding community. The building seemed to be a magnet for free thinkers, marginalized groups, scholars, entrepreneurs, and curious wanderers. Harkening back to the artists interviews in 31 Central, when asked about the change in the neighborhood, artist German Pitre replied: “Yeah its changed, but this was all in the planning… but when people talk about gentrification, that’s been the word you know, and it’s all around the country, but this was planned at least 50 years ago… but today its like a light switch going on… Is it good? … It depends on where you are at. Who’s going to benefit? That’s the thing…”[65] As the neighborhood changed, there was the positive aspect of more access to food, possibly alluding to the much needed grocery store that opened downtown earlier that year, but equivalent negative was the concern of losing access to artist spaces.[66]

An independent study conducted by Americans for the Arts concluded that the direct economic activity of “Nonprofit Arts and Cultural Organizations and Their Audiences in the City of Newark” totaled $178,328,298.00 in the 2015 fiscal year.[67] The staggering numbers in this study includes a breakdown of the millions of dollars in revenue generated to state and local governments, as well as “events related spending” of audiences outside the cost of admission.[68] The total event-related spending was over $68 million for the year, with over 50% of that amount attributed to meals and refreshments.[69] By encouraging artists and non-profits to populate less than desirable properties in targeted geographical areas, developers have a jump on additional long-term investments in the area, potentially leading to cronyism. Coupled with tax abatements, longterm revitalization plans for a neighborhood becomes lucrative for rich landholders, but is a destabilizing factor in local and often marginalized communities.

“Newark is Not the Next Brooklyn,” the Mayor Said So

Mayor Ras Baraka boldly stated in a 2017 vlog “Newark is not the next Brooklyn” in response to cynical comments about redevelopment. The Mayor makes a strong case for the quality of life for Newark residents, and points out many of the redevelopment projects are in abandoned buildings in forgotten areas of town. Citing the Hahne’s building revitalization project on Halsey St, just a short walk from 31 Central, the Mayor noted there were regulations in place to provide low income housing for 40% of the residents, a fact that is missing from Hahne & Co’s rental platform.[70] It is hard to argue with the Mayor’s vision of Newark, a place where the local community has access to quality retail and housing, but his insistence of this revitalization without displacement seems to be a utopian dream. There has already been community displacement, such as the Brick Towers site. Artists as well as entrepreneurs from the LGBTQ community on Halsey Street might be surprised at being glossed over as their niche communities struggle with displacement. Scorsone reacted to the same vlog “…if empty space is repurposed, there still remains the risk that the price of rentals will increase beyond the means of many current residents and small business owners, including Newark’s LGBTQ community and the local entrepreneurial projects of Black lesbians.”[71] Less than two years after the Mayor’s vlog, all the remaining tenants at 31 Central, including the LGBTQ Community Center were required to vacate the building.[72]

The relationship between economic growth and the arts in Newark was made clear. In a 2016 report Mayor Baraka unabashedly declared the “an infusion of arts as the anchor for economic growth.”[73] Son of a famed poet, Mayor Baraka understands that municipal interests need to be coupled with community interests for symbiotic success. Thinking about the amount of economic impact artists and grass-roots organizations have on a local economy begs the question of instability. Between increasing property value over time, and being a stimulus for other economic sectors, specifically bars and restaurants, why have local governments and developers not protected this economic engine? Is there a fear of comradery between communities and artists against rapid unchecked gentrification? Why not work to stabilize artists and grass-roots organizations as beacons within the community?

Circling back to the 1979 publication by Perloff, by 1979 he had identified the problem and offered the solution of “artist colonies.”[74] One issue with the artists living and working in a factory space is zoning. Originally zoned for commercial use, factories need to be rezoned for residential space. Since apartments can be rented at higher rates than artist studios, especially when renting to artists beforehand, many developers wouldn’t see this as the best option to make the most money.

Artists need spaces that are zoned for mix use. In general artists do not keep regular hours, can make noise or use materials which create noxious fumes.[75] Within a proposed artist colony, artists could rent, rent to own, or purchase spaces that would be suitable for living, working, and gathering. Easily accessible to public transportation, spaces could also be utilized by grassroots spaces and start-ups, potentially engaging in a collective or cooperative rental. Although this type of development would be less lucrative for developers, it would create stability for an economic engine within the city. This would also prevent artists and nonprofits from engaging in the brand of gentrification that disenfranchises and displaces local communities, or forces people to occupy sick buildings while redevelopers wait them out.

Conclusion: I Have the Key in My Hand, All I have to Find is the Lock[76]

The international art star Willie Cole was raised in Newark. Working in a studio in the Ironbound before the mass influx of artists from elsewhere, Cole used the environment of his studio space and the city to inspire and guide his work. Sourcing materials from the streets and forgotten spaces of the city he is engaged with, the artist repurposes anxious objects like irons, windows, shoes, and other items associated with domestic life into key components within his oeuvre.[77] Running into dead ends while searching for information about Cole’s now demolished studio and gallery at Lum Lane in the Ironbound, I began looking at catalogs, books, and websites searching for clues. Literally at a loss for words, I shifted my thoughts to Cole’s works of art.

©Studio Museum Harlem

Domestic ID II took up residence in my mind while thinking about artists, environment, and gentrification. The windows used to create this piece were from hothouse structures, noted as being “among the many collections of found objects that filled Cole’s Newark loft.” Cole has a long personal history with irons, but the influence of his environment is undeniable. His studio was in an old sweatshop, and after he began his initial works using the irons, he randomly discovered a scorch mark left from an iron of days passed on his studio floor. “Need I say, I got the message?”[78]

Looking at the scorched humanlike “faces” within the window panes of Domestic ID II, I think about the anxious irons held in Coles hands as he applied pressure to the paper. The amount of pressure applied determines the outcome, and no scorch is exactly the same. The scorches from 1991 foreshadowed the different outcomes of artists engaging with their environment, and can be analogous to the varying degrees of gentrification.

The view of gentrification from an artists perspective in the city has opened up a new way of seeing the process, as well as a slew of new questions. One of the major questions that came up through the investigation of the building’s health at 31 Central was: How does the health of a building affect the groundwater on and around the site? I also wanted to learn more about the conditions at Brick Towers in comparison to 31 Central, and dive deeper into stories of negligence as a tool for displacement. Fortunately some questions had clear answers, like the direct effect of arts and nonprofit organizations on the local economy.

The most important thing I feel this research has accomplished is drawing a direct connection between blight, tax abatements, and the true long-term cost to the city and its residents. The New Jersey tax abatement program is not like every other state. Not every state completely cuts school funding out of abatements, and my hope is that additional research and reports will be conducted on these incentives. An additional point on this research is that it was done by someone who identifies with the community they are studying. My previous work in the arts granted me access to 31 Central over a decade before I ever considered writing about it.

More research needs to be done on sick buildings, gentrification, and artists living and working conditions. Although artists are involved with the gentrification process, and can be seen as benefitting from it, the long-term costs are unknown. I took heed when the Mayor made a call to action, not a call to cynicism, and hope through additional research and dialogue relationships between artists, municipalities, real estate developers and local communities, can become more equitable for everyone involved.

[1] Patterson Sims and Leslie King-Hammond, Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands (Rutgers University Press, 2006), 90. Willie Cole is a native Newark artist, renowned for his work and respected by both local and international arts communities.

[2] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280

[3] Kathe Newman, “Newark, Decline and Avoidance, Renaissance and Desire: From Disinvestment to Reinvestment,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 34–48. Kristyn Scorsone, “Invisible Pathways,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (May 1, 2019): 190–217, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.190

[4] ThePoguesOfficial, The Pogues – Dirty Old Town, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s11BuatTuXk.

[5] Patti Smith, Just Kids (Stockholm: Brombergs, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bromberg, Bloomsbury, 2010), 213.

[6] Patti Smith, Just Kids (Stockholm: Brombergs, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bromberg, Bloomsbury, 2010), 213.

[7] Patti Smith, Just Kids (Stockholm: Brombergs, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bromberg, Bloomsbury, 2010), 213.

[8] Patti Smith, Just Kids (Stockholm: Brombergs, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bromberg, Bloomsbury, 2010), 213.

[9] Her back and haunches are subdued in shadow, her legs drawn are up in the fetal position and her body is completely turned towards the windows with the exception of her head. Skin is aglow with natural light pouring in from the large windows, and Smith’s anti-halo of shaggy hair contrasts with the half of her face bathed in light, while the other half is in shadow as she looks away from the window and directly at the camera. Her gaze is focused, uninterrupted, vulnerable, and yet strong as she most likely is looking through the camera and directly at her comrade, Mapplethorpe. Taking a closer look at the image it is clear to see the white brick wall, and can note the absence of moldy drywall described in Smith’s passage. The pipes seem to be tamed from their chaotic steaming, at least in the amount of time it took to capture the image. Other important visual notes include the windows and their frames. Smith alludes to the difficult task taken up by artists of “cleaning up and clearing out” spaces so they are functional once more, going on to comment about cleaning windows, and artists bringing the light back in. The windows in the image show small signs of fracture in the wired glass, but are clean and providing the necessary lighting for the scene. The window sills and frames are also lacking in peeling paint, thoroughly scraped, possibly repainted, and seemingly functional, as they don’t appear to be painted shut.

[10] Patti Smith, Just Kids (Stockholm: Brombergs, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, Bromberg, Bloomsbury, 2010), 213.

[11] For architectural style see “24 Bond Street,” Village Preservation, January 1, 2010, https://www.villagepreservation.org/lpc_application/24-bond-street/ For detail of style see “New York Architecture Images-,” accessed November 30, 2020, http://www.nyc-architecture.com/STYLES/STY-Renaissance.htm

[12] Smith describes how Mapplethorpe was able to afford the “raw space,” it was purchased for him by Sam. Sam Wagstaff was an art collector, curator, and a lover to Mapplethorpe.(a.) Like many artists, Mapplethorpe was unable to afford the proper space to create his work, and was forced to rely on people within his community for space.

a. Tate, “‘Patti Smith’, Robert Mapplethorpe, 1976,” Tate, accessed November 24, 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/robert-patti-smith-ar00186

[13] “AN ARTISTS’ COLONY IS EMERGING IN NEWARK (Published 1985),” The New York Times, February 26, 1985, sec. New York, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/26/nyregion/an-artists-colony-is-emerging-in-newark.html

[14] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; 391-392.

[15] Port Authority NY NJ, “PATH History,” accessed November 17, 2020, https://www.panynj.gov/path/en/about/history.html

[16] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; 395.

[17] Department of the Public Advocate, “Reforming the Use of Eminent Domain for Private Redevelopment in New Jersey” (State of New Jersey, May 18, 2006), http://www.njeminentdomain.com/PAReport%20On%20Eminent%20Domain%20For%20Private%20Redevelopment.pdf, 7.

Designating an Area as Blighted

To use eminent domain for private redevelopment in New Jersey a municipality must first find that an area is “blighted,” as required by the Constitution. The Legislature has established that for the purposes of using eminent domain for private redevelopment any one of the following seven criteria would make an area blighted:

a. The generality of buildings are substandard, unsafe, unsanitary, dilapidated, or obsolescent, or possess any of such characteristics, or are so lacking in light, air, or space, as to be conducive to unwholesome living or working conditions.

b. The discontinuance of the use of buildings previously used for commercial, manufacturing, or industrial purposes; the abandonment of such buildings; or the same being allowed to fall into so great a state of disrepair as to be untenantable.

c. Land that is owned by the municipality, the county, a local housing authority, redevelopment agency or redevelopment entity, or unimproved vacant land that has remained so for a period of ten years prior to adoption of the resolution, and that by reason of its location, remoteness, lack of means of access to developed sections or portions of the municipality, or topography, or nature of the soil, is not likely to be developed through the instrumentality of private capital.

d. Areas with buildings or improvements which, by reason of dilapidation, obsolescence, overcrowding, faulty arrangement or design, lack of ventilation, light and sanitary facilities, excessive land coverage, deleterious land use or obsolete layout, or any combination of these or other factors, are detrimental to the safety, health, morals, or welfare of the community.

e. A growing lack or total lack of proper utilization of areas caused by the condition of the title, diverse ownership of the real property therein or other conditions, resulting in a stagnant or not fully productive condition of land potentially useful and valuable for contributing to and serving the public health, safety and welfare.

f. Areas, in excess of five contiguous acres, whereon buildings or improvements have been destroyed, consumed by fire, demolished or altered by the action of storm, fire, cyclone, tornado, earthquake or other casualty in such a way that the aggregate assessed value of the area has been materially depreciated.

[g. Criterion (g) only applies to the use of tax abatements and specifically indicates that it is not a basis for a blight declaration for eminent domain purposes.]

h. The designation of the delineated area is consistent with smart growth planning principles adopted pursuant to law or regulation.4

3 New Jersey Constitution, Art. 8, § 3, ¶1.

4 N.J.S.A. § 40A:12A-5

[18] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 396.

[19] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 392.

[20] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 392-393.

[21] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 392-393.

[22] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 398.

[23] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280:398.

[24] “Hoboken Is Burning,” Hoboken Historical Museum (blog), accessed December 14, 2020, https://www.hobokenmuseum.org/hoboken-is-burning/

[25] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; 398.

[26] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280: 406.

[27] “City Without Walls,” City Without Walls, accessed December 12, 2020, http://www.cwow.org/ For reference to artists’ beacon see David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; 400.

[28] David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; 400.

[29] Newark Museum established 1909 currently known as Newark Museum of Art, see “History | Newark Museum,” accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.newarkmuseumart.org/history Paul Robeson established 1979, see “About – Paul Robeson Galleries,” accessed December 12, 2020, https://paulrobesongalleries.expressnewark.org/about/ Aard Studio Gallery established 1979, seeGallery Aferro, “Gladys Barker Grauer,” Gallery Aferro, November 16, 2018, https://aferro.org/art-shop-2/gladys-barker-grauer/ The Works Gallery establishment date unknown, see Rowan University Art Gallery, “Willie Cole : Deep Impressions” (Rowan University, 2012), David B. Cole, “Artists and Urban Redevelopment,” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407, https://doi.org/10.2307/214280; “AN ARTISTS’ COLONY IS EMERGING IN NEWARK (Published 1985),” The New York Times, February 26, 1985, sec. New York, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/26/nyregion/an-artists-colony-is-emerging-in-newark.html

[30] Matthew Boxer, “A Programmatic Examination of Municipal Tax Abatements” (State of NJ Office of the State Comptroller, August 18, 2010), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/tax_abatement_report.pdf; 1.

[31] Matthew Boxer, “A Programmatic Examination of Municipal Tax Abatements” (State of NJ Office of the State Comptroller, August 18, 2010), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/tax_abatement_report.pdf; All information regarding tax abatements in this paragraph is from the source listed.

[32] Matthew Boxer, “A Programmatic Examination of Municipal Tax Abatements” (State of NJ Office of the State Comptroller, August 18, 2010), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/tax_abatement_report.pdf; 12.

[33] Matthew Boxer, “A Programmatic Examination of Municipal Tax Abatements” (State of NJ Office of the State Comptroller, August 18, 2010), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/tax_abatement_report.pdf; All information regarding tax abatements in this paragraph is from the source listed.

[34] OECA US EPA, “EJSCREEN: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool,” Collections and Lists, US EPA, September 3, 2014, https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen; Data analysis of Black, Hispanic, and white populations.

[35] Matthew Boxer, “A Programmatic Examination of Municipal Tax Abatements” (State of NJ Office of the State Comptroller, August 18, 2010), https://www.nj.gov/comptroller/news/docs/tax_abatement_report.pdf; 11, 16.

[36] Karina Ioffee, “Newark Revival Turns Old Factories into Homes,” Reuters, June 8, 2010, https://www.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-49146320100608;

[37] Madeline Bilis, “3 Things to Know About Living in a Converted Factory, According to Someone Who Does,” Apartment Therapy, accessed November 17, 2020, https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/living-in-a-converted-factory-36741011;

[38] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; (20:15 – 20:26)

[39] Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (32:02 – 32:07)

[40] “31 Central Meeting Notice June 2018,” Colleen Gutwein (blog), October 13, 2020, http://colleengutwein.com/31-central-meeting-notice-june-2018/;

[41] Jared Kofsky, “New Details Revealed About 10-Story Development Plan for Newark’s 31 Central Site,” Jersey Digs (blog), July 23, 2020, https://jerseydigs.com/new-details-revealed-31-central-avenue-newark-development/;

[42] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s;

[43] Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (16:30 – 17:05)

[44] Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (1:16 – 1:26).

[45]Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; (6:57 – 7:21), Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (3:34 – 4:18)

[46] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; (18:14 – 23:54), quote by artist Akintola Hanif (22:43 – 23:14)

[47] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; artist Jerry Gant (20:28 – 21:06)

[48] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; artist German Pitre (18:18 – 20:22)

[49] Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (8:09 – 9:20) Roof damage, landlord call and ill-repaired roof information from the paragraph are all from this source.

[50] Ritchie C. Shoemaker and Dennis E. House, “Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) and Exposure to Water-Damaged Buildings: Time Series Study, Clinical Trial and Mechanisms,” Neurotoxicology and Teratology 28, no. 5 (September 1, 2006): 573–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2006.07.003; 574.

[51] Jasmine Garsd, “If Walls Could Talk: What Lead Is Doing To Our Students,” NPR.org, accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/04/14/398314591/if-walls-could-talk-what-lead-is-doing-to-our-students;

[52] Office of Lead Hazard Control and Healthy Homes, “Lead Paint Safety: A Field Guide For Interim Controls in Painting and Home Maintenance” (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development), accessed December 12, 2020, https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/DOC_11878.PDF; 4.

[53] Katrina Bello, “Katrina Bello,” accessed December 14, 2020, https://katrinabello.com/;

[54] Katrina Bello (artist) in discussion with the author, June 2018.

[55] Colleen O’Neal, 31 Central: Lowell Craig Interview, Oral Interview, SoundCloud, accessed December 12, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/colleen-gutwein/31-central-lowell-craig-interview; (35:26 – 36:43)

[56] For arts see “Redevelopment Plan – Powerhouse Arts District,” accessed December 14, 2020, https://data.jerseycitynj.gov/explore/dataset/powerhouse-arts-district-redevelopment-plan/; For music see “Goodbye, Uncle Joe’s Jersey City’s Indie Rock Club Closes after 112 Years,” Hudson Reporter Archive (blog), May 20, 2005, https://archive.hudsonreporter.com/2005/05/20/goodbye-uncle-joes-jersey-citys-indie-rock-club-closes-after-112-years/;

[57] Darren Tobia, “As Construction Boom Continues, Social Media Influencers Are Becoming Preservationists,” Jersey Digs (blog), September 16, 2020, https://jerseydigs.com/as-construction-boom-continues-social-media-influencers-are-becoming-preservationists/; The entire paragraph is informed by the comment section below the article. “Quasi-anonymous” refers to the commentators, although they have a nickname “handle” they do not reveal their true identity.

[58] Kathe Newman, “Newark, Decline and Avoidance, Renaissance and Desire: From Disinvestment to Reinvestment,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 34–48;

[59] Kathe Newman, “Newark, Decline and Avoidance, Renaissance and Desire: From Disinvestment to Reinvestment,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 42.

[60] Kathe Newman, “Newark, Decline and Avoidance, Renaissance and Desire: From Disinvestment to Reinvestment,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 41 – 45. This entire paragraph is informed by the source.

[61] Nixon, Rob. “Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism of the Poor.” Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies 13.2-14.1, no. 2–1 (September 2006): 14–37.

[62] Kristyn Scorsone, “Invisible Pathways,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (May 1, 2019): 190–217, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.190;

[63] Kristyn Scorsone, “Invisible Pathways,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (May 1, 2019): 191, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.190;

[64] Out In Jersey, “A Year of Transition at Newark LGBTQ Center,” Out In Jersey (blog), March 22, 2017, https://outinjersey.net/transition-at-newark-lgbtq-center/;

[65] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; (24:01- 24:53)

[66] Lowell E Craig, Index Art Center, 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s; (33:34 – 33:55)

[67] Americans for the Arts, “The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts and Cultural Organizations and Their Audiences in the City of Newark, NJ,” 2015, https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2017/by_program/reports_and_data/aep5/map/NJ_CityOfNewark_AEP5_OnePageSummary.pdf.

[68] A notation on art galleries: they are free. For profit and nonprofit galleries generally host free and public events, unless otherwise noted.

[69] Americans for the Arts, “The Economic Impact of Nonprofit Arts and Cultural Organizations and Their Audiences in the City of Newark, NJ,” 2015, https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2017/by_program/reports_and_data/aep5/map/NJ_CityOfNewark_AEP5_OnePageSummary.pdf.

[70] For income housing percentage see City of Newark NJ, Mayor’s Vlog: Newark Is NOT Brooklyn, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xvj60aiM1GE; For low-income housing accessibility see “Apartments in Newark NJ – Newark Apartments | Hahne & Co,” Hahne & Co., accessed December 13, 2020, https://www.livehahne.com/;

[71] Kristyn Scorsone, “Invisible Pathways,” The Public Historian 41, no. 2 (May 1, 2019): 190–217, https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.190; 215.

[72] “31 Central Meeting Notice June 2018,” Colleen Gutwein (blog), October 13, 2020, http://colleengutwein.com/31-central-meeting-notice-june-2018/;

[73] City of Newark, “Fall 2016 State of the City Semi-Annual Report,” Issuu, accessed October 13, 2020, https://issuu.com/cityofnewark/docs/sotc_fa2016-finalrev4.

[74] Los Angeles. University of California and Harvey S. Perloff, The Arts in the Economic Life of the City: A Study (New York: American Council for the Arts, 1979), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000746427.

[75] Los Angeles. University of California and Harvey S. Perloff, The Arts in the Economic Life of the City: A Study (New York: American Council for the Arts, 1979), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000746427.

[76] WAX TAILOR, Wax Tailor – Que Sera, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSsgjm55eKE. (1:50)

[77] Patterson Sims and Leslie King-Hammond, Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands (Rutgers University Press, 2006), 33.

[78] Patterson Sims and Leslie King-Hammond, Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands (Rutgers University Press, 2006), 94.

Primary Sources:

Images from Inside 31 Central, 2016

Colleen Gutwein. “31 Central, 9/12/2016,” October 13, 2020. http://colleengutwein.com/31-central-9-12-2016/.

These are images I took inside one artist studio in 2016 , which had also previously been used as a shared studio space and event space. The last two images are from the hallway on the way out. I am using these images as a base to understanding how the building can be a representation of Sick Building Syndrome. These images will also be used to mark a moment in time when the health of the building was observably poor, as well as gauge the owner and tenants response to the condition of the building.

31 Central Meeting Notice, June 2018

Colleen Gutwein. “31 Central Meeting Notice June 2018,” October 13, 2020. http://colleengutwein.com/31-central-meeting-notice-june-2018/.

This is a photograph I took on June 21, 2018 in a common area on the second floor of 341 Central Avenue, It is a notice to tenants dated June 6, 2018 on behalf of the “Owner” with the anticipated date of demolition, and offer to meet tenants for a one hour discussion within two weeks of the notice. I will be using this letter to prove the negligence of the building owner, allowing tenants to continue to stay and work in a building that is clearly not suitable without proper cleaning, repairs, and inspection.

Fall 2016 State of the City Semi-Annual Report, Newark NJ

City of Newark. “Fall 2016 State of the City Semi-Annual Report.” Issuu. Accessed October 13, 2020. https://issuu.com/cityofnewark/docs/sotc_fa2016-finalrev4.

The semi-annual report is a short document containing the city’s achievements and goals upon publication in 2016. Within the document, the Mayor openly acknowledges the need for artists within the city’s economic plan. In a short but assertive manner, the City of Newark explicitly states the need for art and artists for future economic growth. The clarity wihin this statement will be a foundational element in my overarching theme of gentrification.

New Details Revealed About 10-Story Development Plan for Newark’s 31 Central Site

Kofsky, Jared. “New Details Revealed About 10-Story Development Plan for Newark’s 31 Central Site.” Jersey Digs (blog), July 23, 2020. https://jerseydigs.com/new-details-revealed-31-central-avenue-newark-development/.

This article describes the opaque review process of the building application and surprising revelation of a 10 story condominium complex to be erected upon the destruction of 31 Central, which has yet to happen. I will use this article to further support my argument of the building be ing sick since it is not being saved or improved upon. This article also highlights a clear path of gentrification from artist occupation to condos.

31 Central: mini-documentary

Lowell E. Craig, Index Art Center. 31 Central – Newark, NJ, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIE7vSogZks&t=416s.

This video documents artists working in 31 Central in 2017, showing studios, shots of the building, and artists give testimony to the need for autonomy and cheap rent to be able to create, they also discuss the current condition of their studio spaces and their feelings on the management of the building. This video was created by a studio artist at 31 Central, and integral member of the Newark artists community. The perspective of a complete insider lends the opportunity for the nuclear community of 31 Central artists to give honest and open commentary on their individual and varied experiences at the site. This mini documentary gives me the opportunity to quote and represent the artists in their own words.

Keywords: Toxic, Community, Artist, Sick Building, Gentrification

Secondary Sources:

1. Cole, David B. “Artists and Urban Redevelopment.” Geographical Review 77, no. 4 (1987): 391–407. https://doi.org/10.2307/214280.

This journal article tracks artists forced from New York City due to hight rents into three New Jersey cities, Hoboken, Jersey City, and Newark and their role in the gentrification process. I will use this research to better understand the artist’s role in gentrification and their effect on the communities within the cities they move to, both financial and personal. This writing also helps to discern the need and difficulty accessing New York City for their work.

2. May, Earl Chapin. The Prudential :A Story of Human Security /. [1st ed.]. Garden City, N.Y. :, 1950. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b31148.

This book, written in 1950, gives a historical interpretation of the Prudential Insurance Company, written by an author clearly defined as ally. This book will provide a better understanding of the company’s business ambitions, and its long-term goals. Prudential plays a big role in the City of Newark and I am reading to understand the reach of the business into the surrounding communities. Being the owner (through a subsidiary) of 31 Central, I want to understand the mission and driving influences behind the company, the mission, and perceived ethical responsibilities.

3. Newark Arts. “Newark Creates: A Community Cultural Plan for Newark 2018 -2028.” Accessed October 4, 2020. https://newarkarts.org/newark-creates/.

Newark Arts, formerly the Newark Arts Council, has created a ten year plan for the arts within Newark, heavily relying on the participation of artists and grassroots organizations for content, but supported financially by institutions like Rutgers and Prudential. I want to clearly understand the perceived needs of the artists community though Newark Arts, and how they are discussed and met in the plan. The Cultural Plan also includes information from studies and surveys conducted within the Newark Arts community in 2017 and 2018, key years of the demise of 31 Central.

4. Schnapf, Lawrence P, and Lawrence Schnapf. “ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN REAL ESTATE AND CORPORATE TRANSACTIONS.” 2003, n.d., 150. https://www.environmental-law.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Env-Issues-in-Bus-Trans-CLE-03.pdf.

This is a journal article published by a law firm specializing in environmental issues. This article clearly states environmental rules of law in corporate real estate dealings, as well as exposes though admission, grey areas and loop holes. This article provides a basic understanding of what is permissible, who is liable, and what laws are in place to protect people working, volunteering, and convening knowingly or unknowingly in environmentally unsound buildings. This article also includes laws regarding contaminated groundwater and runoff from neglected buildings, fire inspection, and mold regulations.

5. Markusen, Ann. “Urban Development and the Politics of a Creative Class: Evidence from a Study of Artists.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38, no. 10 (October 1, 2006): 1921–40. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38179.

This article is suggesting the complex nature of artists in formation, location, urban impact, and politics which do not mix with neoliberal urban political regimes, providing a understanding of the multifaceted complex relationships between artists and the cities/communities they are engaged with. Comparison of analysis from the article with experiences of the artists and grassroots organizations inhabiting 31 Central 1990 – 2019 can be used to assess the loss and gains within the individual groups and the immediate community.

Image Analysis:

Hawak/hold (8.7832, -124.5085) is a larger than life charcoal and pastel rendering of a churning sea shown from an aerial perspective completed in 2019 by artist Katrina Bello. This seascape is seemingly incongruent with 31 Central, a sick building in downtown Newark, NJ, but through the close analysis of duality, process, and form, deeper connections are revealed. The drawing represents a point of intersection between the environmental decay at 31 Central, and continued environmental shifts on a global scale.