Claiborne Expressway: An Expressway That Led Treme to Ruin

by Jash Shukla

Site Description:

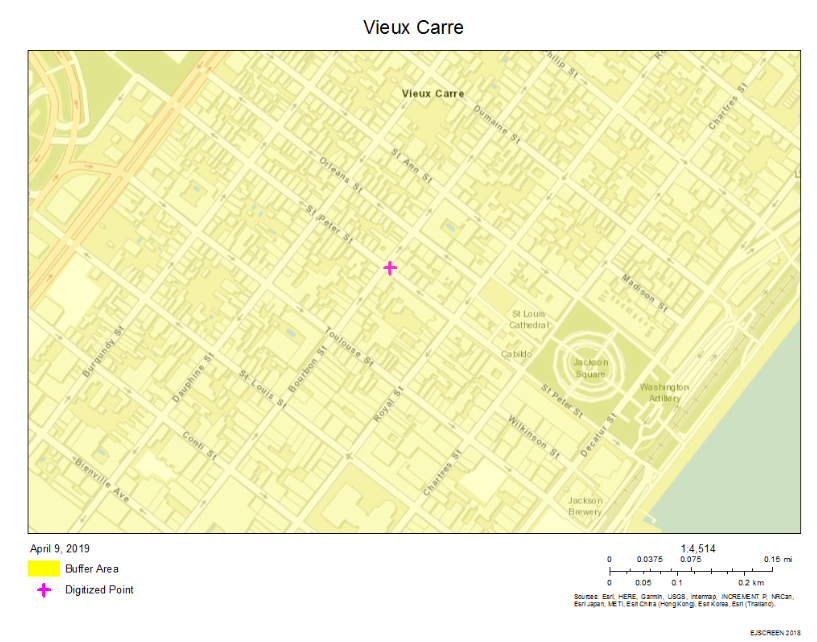

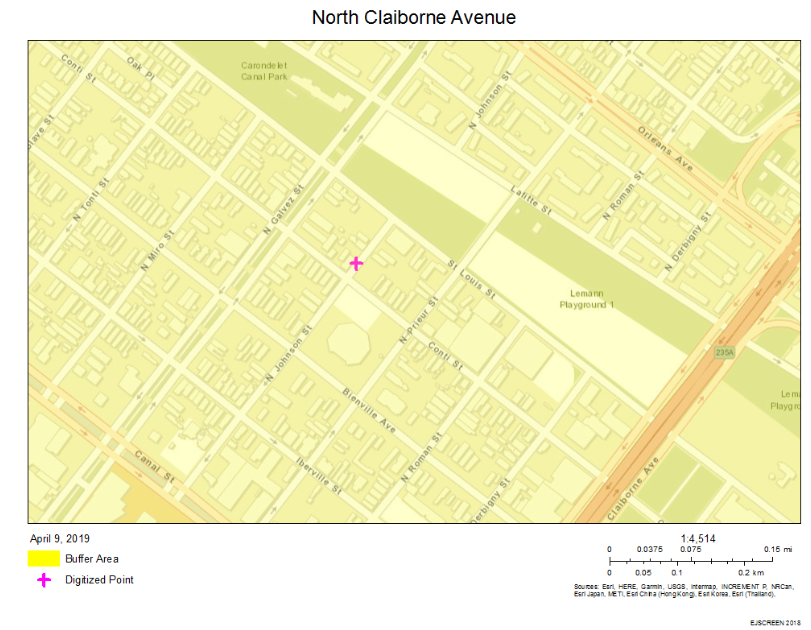

There was a struggle for highway construction in New Orleans in Vieux Carre and Faubourg Treme whose success was determined by the influence in government and resources the community had which Vieux Carre did not lack and the contrast in struggle makes a case for environmental injustice. The focus of the project will be on two sites- the Claiborne Avenue in Faubourg Treme, an African American community, where an elevated highway- Interstate 10 was constructed despite strong opposition from the community and Vieux Carre, a dominantly white community (popularly known as the French Quarter) where there was a proposal to construct a highway- the Riverfront Expressway- but it was successfully stopped. The highway construction through Faubourg Treme on Claiborne Avenue destroyed an important avenue for the African Americans who lived there and operated their businesses. For the African American community, Faubourg Treme was sentimentally valuable because it was amongst the very first neighborhoods where freed slaves settled and lived. On the other hand, Vieux Carre was a predominantly a white neighborhood which became popular post-WWI, here artists settled down and socialized in a neighborhood which had a colonial charm with paved roads. There was a proposal to construct a highway- Riverfront Expressway- that was stopped; the community members and the oldest residents of the city used their old money and influence in the government which the African American community lacked, to stop the highway construction. In brief, there was a struggle in both the neighborhoods but the success of the struggle was determined by the influence and resources a community had which the white community in Vieux Carre did not lack.

Final Report:

I. Introduction

America, in the 1960s and the early 1970s, had the most enviable car culture. It was a time when there were fast cars, cars with a long hood, cars with a long overhang, and cars with sofa-like comfortable seats. To enjoy such cars, there was the newly built infrastructure throughout the nation that made people car dependent. As a result of making a car dependent infrastructure, there were drive-in cinemas wherein people of every age group enjoyed watching a movie from the comfort of their cars, drive-in restaurants where people would pick-up their food without having to step out of their cars, and not to forget the drive-in banks wherein people could have access to bank services from the comfort of their cars. This culture grew as a result of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

However, the highway act of ‘56 had affected many communities throughout the country, especially the minority communities. The interests of the minority community were often ignored and as a result highways were proposed and built through these neighborhoods. Faubourg Treme, an African American neighborhood in New Orleans, was one such neighborhood where the highway, Interstate-10, was built at the cost of the interests and livelihoods of Treme.1 At the same time in New Orleans in the Vieux Carre neighborhood, a white neighborhood, right next to Treme, a highway, Riverfront Expressway, was proposed in 1964, to be built through it.2 However, the whites in Vieux Carre were successfully able to stop the highway construction in a five year long struggle that ended in 1969 as a result of having the resources and influence to stop the highway construction.3 Though the whites were able to stop the highway, it affected them as well given their neighborhood’s close proximity to the highway.

The construction of I-10 in the Treme neighborhood raises a few questions: one, why the highway was built in the Treme neighborhood? Two, was there a revolt to stop the highway construction in Treme? Lastly, how did the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and the Civil Rights legislation affect the highway construction in Treme?

This paper argues that the highway built through the Treme neighborhood was not only unjust, but affected both the Treme and Vieux Carre neighborhoods unequally given the close proximity to the highway. Moreover, the loss in the livelihood in the Treme neighborhood is still fresh in the minds of the former and current residents. There are some organizations dedicated to preserving what is left in the Treme neighborhood and at the same time, creating awareness amongst people as to what happened to the neighborhood from its vibrant past to the present day.

This paper explores what the Highway Act of 1956 was. Next, the paper will briefly discuss the response of the residents of Treme and Vieux Carre to the highway proposals from the accounts of the residents and belligerants, such as Attorney William “Bill” Borah, involved. Furthermore, the paper argues how the communities were affected unequally with Treme the most impacted, using an image contrast between 1968 and 2014 from the Treme neighborhood, demographic data from 1960 and 1980 and the environmental scientific data. Lastly, the paper discusses how the community members in Treme have taken measures to form multiple organizations to preserve what is left in the neighborhood and a study which proposes to remove the highway.

II. Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was a legislation passed under President Eisenhower’s administration. It proposed to build 41,000 miles of highway throughout the nation with the federal government would pay 90% of the costs of the highway in each individual states.4 This legislation was well received of whom the Saturday Evening Post, a popular magazine, and Henry Ford II, grandson of Henry Ford are two notable examples who supported the highway legislation.

Richard Thruelson feels the highway legislation proposed a humongous nation wide project to build highways supported with a budget figure and the length of the proposed highways which are basic facts; however, what is remarkable to note is his analogy with other public works such as the Panama Canal, Grand Coulee Dam, and the St. Lawerence Freeway.5 Thruelson adds that combining the three public works into one consolidated project, the proposed budget of the highway legislation of fifty one billion dollars would be enough to fund twenty nine such consolidated projects.6 The highway legislation indeed was a humongous project especially after the Second World War when Europe was wounded and the US constantly gave financial assistance to Western Europe in the 1950s. Upon reading Thruelson’s article it leaves one with a sense that the highway legislation was massive given its comparison to the other public works. Thruelson further adds that all of the American masses who want the highways are willing to pay it.7 However, Thruelson does not support this point as well as Henry Ford II who considers the highway system to be democratic as it serves the public as they want to be.8

The purpose of bringing democracy into his claim is to answer the opponents of having a nation-wide highway system.9 Further, Ford adds that the highway opponents wanted the city to be designed from, “their [highway opponents] own conception of the ideal city, regardless of what people want.”10 Though serving the needs of the people is an important aspect of democracy, Ford II only bases his views on the rising sales of automobiles and trucks since 1950 and the total from 1964-1966 which was thirty million units.11 Though the sales of vehicles had grown, Ford II fails to consider why the sales grew so much because public transit was in decline.12

Moreover, both Thruelson and Ford II, fail to consider the views of the minority community because they would have been the most affected due to reduced options of mobility as a result of decline in public transit. The 1950s and early 1960s was the civil rights legislation period where there was widespread racism that resulted in far fewer opportunities for the minority community especially the African Americans for upward economic mobility. With fewer opportunities availabe, few individuals from the minority communities could afford an automobile for transportation which many middle-class whites did. As a result the minority communities were the most affected by the decline in public transit and the highway legislation of 1956; as a result of the latter, the highways were built throughout the nation and more often through minority neighborhoods whose interests were often ignored with the whites being able to stop the highway construction when a highway was proposed to be built through their neighborhoods. The highway construction is Faubourg Treme and Vieux Carre neighborhoods in Treme is a notable case of the above point.

III. Onset of Trouble in Treme and Vieux Carre

As a result of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, there were plans to build highways through the Faubourg Treme, the African American neighborhood, and Vieux Carre the white neighborhood in New Orleans. In Vieux Carre, there was a staunch opposition to the highway that resulted in a five year long struggle from 1964 till 1969.13 There were two sides in the struggle the highway proponents- downtown clubs, labor unions, two mayoral administrations, the City Council, the New Orleans Dock Board, the Jewish Merchants Association, the Times-Picayune, and New Orleans Public Service, Inc.14 On the other hand, the highway opposition side included organizations such as Vieux Carre Commission and the Vieux Carre Property Owners Association and the descendents of New Orleans’s early residents who were William “Bill” Borah, Richard “Dick” Baumbach, and Edgar Bloom Stern Jr.15 This struggle is remembered as The Second Battle of New Orleans.16

The Second Battle of New Orleans begins with the official “designation” of the Riverfront Expressway, which was also known as I-310, in the “Interstate System” on October 13, 1964. 17 The highway proponents pushed for the highway aggressively which involved rejecting alternative of having a “tunnel” highway thrice.18 Lastly, Bill Borah recalled that the Times-Picayune, a newspaper, did not publish any letters to the editor because they were the proponents of the highway.19 In brief, the struggle against the highway construction in Vieux Carre was long and difficult because the highway proponents rejected any alternatives of having a highway and tried to stop the voices of highway opposition from being heard.

Despite the difficulties, the opponents were able to stop the highway in 1969.20 It was on August 22, 1969, the FHWA, the Federal Highway Administration removed the Riverfront Expressway, I-310, from the Interstate system.21 According to Eric Avila, the National Historic Preservation Act helped the highway opponents to stop the highway construction.22 Most likely, it was the case of Vieux Carre being able to gain a National Historic Landmark status which neither Avila or Richard Weingroff mention in their work. In contrast to Vieux Carre’s victory, Treme could not stop the highway construction.

Louis Charbonnet who owns a funeral home which survived despite the construction of I-10 because it was situated half a block away from Claiborne Avenue that helped it save from demolition.23 Charbonnet further adds about the opposition of the highway that there was an attempt to organize resistance but it wasn’t enough.24 Charbonnet does not mention the timeline of the struggle with major events but it was a case of the interests of the residents not heard because there were only two to three African Americans in the local government.25

However, there were activists such as Dodie Smith-Simmons and organizations such as NAACP and CORE, Congress of Racial Equality, but they were occupied perhaps with passing the civil rights legislation.26 To which Charbonnet adds that “Trees and flowers and grass was not our main interest at that time” referring to the neutral ground lined-up with oak trees on Claiborne Avenue where the highway was built and addressed the need for passing the Civil Rights Legislation when he said “we were worried about what was going to happen to our children, to us!”27 Charbonnet further believes that by the time the Treme community realized the possible negative effects of the highway, it was too late.28 Here, he does not mention a timeline of the struggle, but what is important to note that the people of color were occupied with passing the civil rights legislation which was very important to end segregation and then try to fight the construction. The civil rights legislation was passed in 1964 and the construction of I-10 began in February, 1966 with the clearing of oak trees.29

As a result of the I-10 constructed on Claiborne Avenue, it changed the landscape of the Treme neighborhood as depicted in the images below. The two images come from two different timelines, the one on the left comes from 1968 whose photographer was Joseph C. Davi and the one on the right is taken from Google Earth in 2014. Not much is known about the photographer Joseph C. Davi, but there is a strong possibility of Davi being on an assignment to take photographs of the site before its destruction.

Upon viewing the image on the left, one is immediately drawn to the lined-up oak trees which is perhaps a reminder of the enligntenment movement in Europe and Louisiana was a colony of France, a European power. The enlightenment movement focussed on the ability to use reason, being logical and rational which the oak trees depict because they are lined-up. Compared to the image on the right, the lined-up oak trees are replaced with a humongous highway. As a result of accomodating this highway, there were some adverse effects on both the Treme and Vieux Carre communities given the close proximity of the neighborhoods.

IV. The Detrimental Highway Effect on Health and Livelihood in Treme

Photograph 1 depicts the most obvious environmental change caused by the I-10, the removal of the lined-up oak trees. Leah Chase, a chef and a resident of the neighborhood, recalls how Claiborne Avenue once was when she describes the lined-up oak trees forming an “umbrella” which is a valid point because one can see in figure 1 that the oak trees cover up the ground on which they stand entirely.31 Chase further adds that the same avenue was the place where the Mardi Gras parade used to take place before the highway was constructed.32 Furhtermore, the lined-up oak trees on Claiborne Avenue were the longest stretch of oak trees in the country that made them unique to the Treme community and historically significant because it was perhaps a reminder of the enlightenment movement.33

The second change seen as a result of the highway was the displacement of people, as many as 500 homes, businesses, and buildings that were removed to accommodate the I-10 on Claiborne Avenue.34 The way it affected livelihoods of the people as a result was because on the same avenue, many African American businesses operated on the avenue; furthermore, in the pre-civil rights era, the African Americans were not allowed to shop in white-owned shops, hence, their only source of shopping or going to restaraunts was on Claiborne Avenue.35 Though, the highway construction began in the post-civil rights era, the district was sentimentally valuable to the residents because in the era of segregation, the shops on Claiborne Avenue being the only source for shopping makes it important for the community members because of the long years the community members spending their shopping times here becomes memorable and builds a feeling of attachment to the community over the years.

Fred Johnson, a resident of the 7th Ward neighborhood adjacent to Treme, felt, “it was a cold calculated business decision.”36 Johnson makes a strong point which actually can be used to argue against the highway act of 1956 because the highways were to benefit corporations who would sell more cars and earn more profit. Henry Ford II is one example who actually said in his speech that he had finished negotiations to open a dealership on the corner of Canal St. and Claiborne Avenue.37 From this on can only imagine a person visiting this dealership and from their he could see cars cruising at speeds in excess of 60 MPH which would compel him to buy a car because he would see a lot of people driving cars and he would not want to miss out on it.

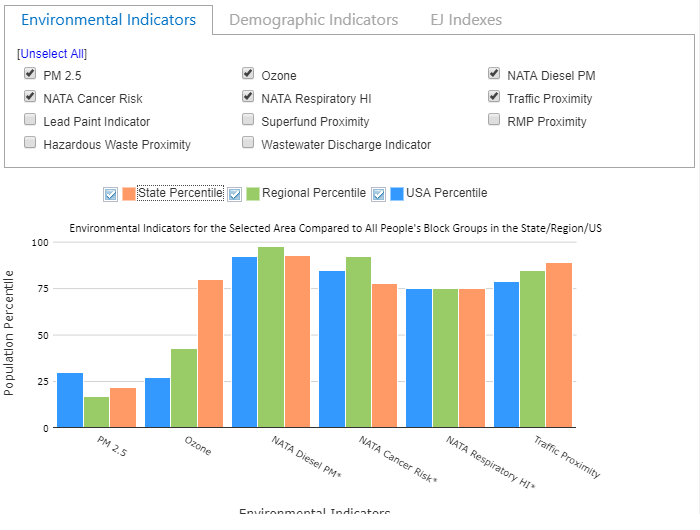

When the highway was fully built, it led to environmental issues such as air pollution which affected the health of the neighborhood as the data from Environmental Protection Agency’s tool- EJScrenn, Environmental Justice Screen, which can be used to extract data from a specific geographic location in the US. Upon extracting data from EJScreen and comparing datasets from both the Treme and Vieux Carre neighborhoods, using percentiles for Traffic Proximity, NATA- National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment- Respiratory and Cancer risk. The purpose of choosing these parameters is because as a result of the highway there are more cars that increases traffic. More cars lead to more emissions that have adverse health effects .

The data shows results that are surprising. The traffic proximity percentiles of both the neighborhoods: Faubourg Treme- 94 and Vieux Carre 85- are not across the opposite spectrum instead illustrate both the neighborhoods have come in close proximity to traffic as the result of the highway but Treme’s traffic proximity higher which shows it is more affected by the highway.38, 39 Both neighborhoods being close to the highway are exposed to pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. All these pollutants are toxic, increase the risk of chronic diseases related to the heart and lungs and increase the risk of acid rain. The NATA Respiratory and Cancer risk is an interesting contrast, the NATA Cancer risk percentile is higher in Vieux Carre in 90-95 percentile compared to 80-90 percentile in Treme which should have been the opposite considering Treme’s closer proximity to traffic and the resulting pollutants from the vehicles.40, 41 Despite the counterintuitive number, the NATA Cancer risk is a great illustration of how both the neighborhoods were affected by the highway considering the similarities in number.

Another important aspect of this event to note is the timeline of the construction- 1966, this is a period just post the passage of the civil rights legislation and suburbanization is in full swing. The effect of suburbanization is reflected in the demographic statistics of the city post 1960 when the population begins to decline and there were more African Americans and Hispanics than the whites. In 1960, the population of New Orleans reached its peak to precisely 627,525 residents whose demographic composition was 62.56% white, 37.21% African Americans and 0.23% others.42 Upon moving to 1980 a period post the rapid suburbanization, the white population shrinks from a dominant 62.56% in 1960 to 42.51% in 1980 and the African Americans composition grew to 55.27% in 1980, up from 37.21% in 1960.43

The demographic statistics is an illustration of the rapid decline in the white population whose only explanation is suburbanization because it was a movement of the white population out of the cities into newly constructed suburban areas that had new infrastructure built specifically to make people dependent on cars. This led to the decrease in the overall population of New Orleans from 627,525 residents in 1960 down to 557,515 in 1980.44 The significance in the decline of the population is the movement of the majority white population out of the city and by 1980 the white population accounted for 42.51%, no longer being the majority population of the city.45

The new infrastructure built post the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 made the masses dependent on cars and highways played an important role when there was nationwide suburbanization. Highways connected the suburbs to the cities which people could use to get to work or travel to the city for the purpose of leisure. Moreover, highways cutting through cities made it possible to get in and out of the city faster which is important because the number of cars on the road would only have made the traffic worse considering the roads within the city which were not as wide as the highways.

Upon considering the views of the Treme resident Leah Chase and Fred Johnson, it leaves one with a strong sense that the highway was unjust to the Treme neighborhood because the highway affected the livelihood of the residents and displaced people and businesses. Furthermore, Treme was historically significant to the community because it is the oldest African American neighborhood in the United States.46 Lastly, the community members had a sense of belonging because in the pre-civil rights era and the civil rights era, African Americans looked to businesses in Treme to shop. The highway also lead to environmental issue of air pollution as the data from EJScreen illustrates that the highway affected both the communities unequally, Treme was the most affected because it was closer to the highway which resulted in a higher traffic proximity percentile and a higher NATA Respiratory risk than Vieux Carre.

V. Claiborne Expressway Today

Today, one only has to see the columns of I-10 expressway to see how the community has responded to the highway. These columns have been painted with oak trees and civil rights leaders.47 The image below showcases one section of the interstate where the columns have been painted. The second column, on the left, seems to be a civil rights activist who appears to be dressed well. The first column, on the left, depicts how the avenue once looked whose cues appear to be a tree in the background and a lamppost and garden with a child on it. The purpose of painting the column is clear which is to serve as a reminder of the past when the Claiborne Avenue was thriving.

Figure 2. The Highway Today.48

As a result of the highway built against the will of the community, there are many organizations today to help improve the neighborhood of which some are the Neighborhood Development Foundation, the Tremé Community Improvement Association and many more. However, the CAHP, Claiborne Avenue History Project, is the most notable organization because it is a “documentary project that collects and curates history about North Claiborne Avenue focusing on the civil rights, culture, and commerce from the Avenue’s heyday.”49 The CAHP has interviewed notable people such as Deacon John Moore, a musician, Sidney Barthelemy, former mayor of New Orleans, Leah Chase and many more whose purpose is to capture and remember their perception of North Claiborne Avenue at its peak.50 The project has its own website wherein one can see some interesting images and a short clip on the homepage. The project also accepts donations on their website and their website is open to public for anyone to access it to see the material they have.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development and the US Department of Transportation funded the Liveable Claiborne Communities, LCC, Study to analyze “community revitalization” and put forward “recommendations for the Claiborne Corridor with transportation and redevelopment scenarios.”51 The study has come up with three possible scenarios in which the first two scenarios suggest keeping the I-10, have a Streetcar functioning alongside the expressway and have a bus service alongside the expressway.52 Lastly, the third scenario is divided into two possible options- 3a and 3b both of which involves removing the highway between Tulane Ave. and St. Bernard Ave and have a Streetcar and bus service; the only difference being the number of jobs it would create as a result of the LSU University Medical Center and VA Hospitals which would rise from 1270 jobs from scenario 3a to 2470 jobs from scenario 3b.53

The scenario 3b should be considered to revitalize the community because it not only involves removing the highway altogether, but create more jobs than any other scenario- 600 in Scenario 1, 1070 in Scenario 2 and 1270 in Scenario 3a.54 Moreover, considering the fact that the I-10 was built against the interests of the Treme residents, it makes a strong case to remove the highway altogether. Andreanecia Morris, a Housing Expert and a member of the Claiborne Corridor Improvement Coaltion, feels if the neighborhood should be improved, it should be done for the people who will settle down there and already lived there.55 Morris makes an interesting point because if the I-10 is removed it could possibly attract the former residents to come back to the neighborhood which would be an important step to restore the Treme neighborhood as it was in the 1950s when it was thriving. However, which scenario is implemented only time will tell.

VI. Conclusion

Considering the little to no struggle in Treme whose resident did not want the highway due to the sentimental value the neighborhood had for the Treme residents which included being the oldest African American neighborhood and an area where the African American businesses operated before and during the civil rights era. The I-10 expressway was unjust to the Treme residents as it affected their livelihood because people and businesses were displaced. Moreover, the Vieux Carre a neighborhood which was in close proximity to the neighborhood also got affected considering the scientific data from EJScreen which showed it had a higher NATA Cancer risk compared to Treme. In the end, the I-10 expressway not only affected the Treme neighborhood but also the Vieux Carre neighborhood.

Endnotes

1. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate

2. Richard F. Weingroff “The Battle of New Orleans-Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans/cfm.

3. Richard F. Weingroff “The Battle of New Orleans- Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310) ,” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans/cfm. As Weingroff quotes a press release of Secretary Volpe.

4. “The Interstate Highway System,” History.com, last modified August 21, 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/us-states/interstate-highway-system.

5. Richard Thruelsen,”Coast to Coast Without a Stoplight,” Saturday Evening Post, October 1956, 54.

6. Richard Thruelsen,”Coast to Coast Without a Stoplight,” Saturday Evening Post, October 1956, 54.

7. Richard Thruelsen,”Coast to Coast Without a Stoplight,” Saturday Evening Post, October 1956, 23.

8. Henry Ford II, “The Highway System,” Vital Speeches Of The Day, September 1966, 691.

9. Henry Ford II, “The Highway System,” Vital Speeches Of The Day, September 1966, 691.

10. Henry Ford II, “The Highway System,” Vital Speeches Of The Day, September 1966, 691.

11. Henry Ford II, “The Highway System,” Vital Speeches Of The Day, September 1966, 690.

12. Jonathan English, “Why Did America Give Up on Mass Transit?,” last modified August 31, 2018, https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2018/08/how-america-killed-transit/568825/. This source is only used to cite the decline in public transit however, the author Jonathan English is biased towards automobile industry.

13. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans-

Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

14. Eric Avila, Folklore of the Freeways, (Minneapolis: University of Minnessota Press, 2014) 93.

15. Eric Avila, Folklore of the Freeways, (Minneapolis: University of Minnessota Press, 2014) 94.

16. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans- Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

17. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans – Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

18. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans- Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

19. Laine Kaplan-Levenson,”The Second Battle of New Orleans,” last modified April 21,2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/second-battle-new-orleans. The author quotes Bill Borah from the interview with him.

20. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans

– Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

21. Richard F. Weingroff, “The Battle of New Orleans

– Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310),” Department of Transportation, last modified June 27, 2017, https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm. Weingroff even has a quote from the press release of Secretary John Volpe.

22. Eric Avila, Folklore of the Freeways, (Minneapolis: University of Minnessota Press, 2014) 96.

23. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate. The author quotes Louis Charbonnet from the interview with him.

24. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate. The author quotes Louis Charbonnet from the interview with him.

25. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate. The author quotes Louis Charbonnet from the interview with him.

26. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate. Here the author quotes Dodie Smith-Simmons, an activist, from her interview.

27. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate. The author quotes Louis Charbonnet from the interview with him.

28. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate.

29. “Tree Salvage Work Started,” The Times-Picayune, (New Orleans, LA), Feb. 10, 1966.

30. Image on the left from New Orleans Public Library Archives- Joseph C. Davi. North Claiborne Ave., showing oaks, August 29, 1968, New Orleans Public Library Archives, accessed on May 10, 2019,

http://nutrias.org/photos/streets/nclaiborne.htm .Image on the right from google Earth- Google Earth 2014, accessed May 10, 2019. Accessed from http://architecture.tulane.edu/preservation-project/timeline-entry/1435. There is juxtaposition in the dates mentioned in the second link. While the New Orleans Public Library mentions Aug. 29, 1968, the second link says the image is from 1966.

31. Untitled video, Claiborne Avenue History Project, https://claiborneavenue.wordpress.com/.

32. Untitled video, Claiborne Avenue History Project, https://claiborneavenue.wordpress.com/.

33. Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate,” last modified May 5, 2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate.

34. “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future,” Youtube video, 7:25, posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism,” May 11, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M.

35. “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future,” Youtube video, 7:25, posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism,” May 11, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M.

36. “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future,” Youtube video, 7:25, posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism,” May 11, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M

37. Henry Ford II, “The Highway System,” Vital Speeches Of The Day, September 1966, 690.

38. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018): 0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.964079,-90.079080, LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 789, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping tool] accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/, accessed on April 9, 2019. This dataset is the Faubourg Treme neighborhood. One can access the data by going to EJScreen and entering the coordinates.

39. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018):0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.958650,-90.065615,

LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 1,945, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping Tool] accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/, accessed on April 9, 2019.

This dataset is the Vieux Carre neighborhood. One can access the data by going to EJScreen and entering the coordinates.

40. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),

EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018):0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.958650,-90.065615,

LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 1,945, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping Tool] accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/, accessed on April 9, 2019.

This dataset is the Vieux Carre neighborhood. One can access the data by going to EJScreen and entering the coordinates.

41. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018): 0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.964079,-90.079080, LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 789, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping tool] accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/, accessed on April 9, 2019. This dataset is the Faubourg Treme neighborhood. One can access the data by going to EJScreen and entering the coordinates.

42. Bernardo Espinosa, “Historical Population By Race Over 300 Years. [National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) dataset],” https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u, accessed on May 16, 2019.

43. Bernardo Espinosa, “Historical Population By Race Over 300 Years. [National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) dataset],” https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u, accessed on May 16, 2019.

44. Bernardo Espinosa, “Historical Population By Race Over 300 Years. [National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) dataset],” https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u, accessed on May 16, 2019.

45. Bernardo Espinosa, “Historical Population By Race Over 300 Years. [National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) dataset],” https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u, accessed on May 16, 2019.

46. “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future,” Youtube video, 7:25, posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism,” May 11, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M

47. Katy Reckdhal,” A Divided Neighborhood Comes Together under an Elevated Expressway,” last modified August 20, 2018, https://nextcity.org/features/view/a-divided-neighborhood-comes-together-under-an-elevated-expressway.

48. Christine Carlo, View under the Elevated I-10 Claiborne Avenue Expressway, 2014, Tulane University, accessed May 10, 2019, http://architecture.tulane.edu/sites/default/files/styles/600w/public/img_1_carlo_2014_1.jpg?itok=_XCdJLG5. Endnote for figure 2.

49. “Claiborne Avenue History Project (CAHP),” Kickstarter, accessed May 13, 2019, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/claiborneavenue/the-claiborne-avenue-history-project-cahp.

50. “Claiborne Avenue History Project (CAHP),” Kickstarter, accessed May 13, 2019, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/claiborneavenue/the-claiborne-avenue-history-project-cahp.

51. “Livable Claiborne Communities Study,” City of New Orleans, last modified August 9, 2017, https://www.nola.gov/city/livable-claiborne-communities/. This source is used only to cite the LCC study description text which is much simplified.

52. “Claiborne Expressway,” Congress For The New Urbanism, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/claiborne-expressway. I use this source because it simplifies the LCC study. However, readers can view the actual study in the URL provided in footnote 51 at the bottom of the page.

53. “Claiborne Expressway,” Congress For The New Urbanism, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/claiborne-expressway.

54. “Claiborne Expressway,” Congress For The New Urbanism, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/claiborne-expressway.

55. “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future,” Youtube video, 7:25, posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism,” May 11, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M.

Bibliography

- Avila, Eric. Folklore of the Freeways. Minneapolis: University of Minnessota Press, 2014.

- “Claiborne Avenue History Project (CAHP).” Kickstarter. Accessed May 13. 2019, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/claiborneavenue/the-claiborne-avenue-history-project-cahp.

- “Claiborne Expressway.” Congress For The New Urbanism. Accessed May 16, 2019. https://www.cnu.org/what-we-do/build-great-places/claiborne-expressway

- “Claiborne Avenue: Past, Present, and Future.” Youtube video, 7:25. Posted by “The Congress for the New Urbanism.” May 11, 2012.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lw-kuORzF4M

- “Claiborne Avenue History Project (CAHP).” Kickstarter. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/claiborneavenue/the-claiborne-avenue-history-project-cahp.

- “Construction Of The Elevated I-10 Claiborne Avenue Expressway Begins.” Tulane School of Architecture. Accessed May 11, 2019. http://architecture.tulane.edu/preservation-project/timeline-entry/1435

- English, Jonathan. “Why Did America Give Up on Mass Transit?.” CityLab. Last modified August 31, 2018. https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2018/08/how-america-killed-transit/568825/.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018): 0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.964079,-90.079080, LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 789, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping tool] Accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/. Accessed on April 9, 2019.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EJSCREEN Report (Version 2018):0.25 mile Ring Centered at 29.958650,-90.065615, LA, EPA Region 6, Approximate Population: 1,945, Input Area (sq. miles): 0.20. [Mapping Tool] Accessed from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/. Accessed on April 9, 2019.

- Espinosa,Bernardo. Historical Population By Race Over 300 Years. [National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) dataset]. Accessed from https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u. Accessed on May 16, 2019.

- “Faubourg Treme.”Tulane School of Architecture. Accessed May 10, 2019, http://architecture.tulane.edu/preservation-project/place/359.

- Ford II, Henry. 1966. “The Highway System.” Vital Speeches of the Day 32 (22): 690. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9868021&site=eds-live.

- Kaplan-Levenson, Laine. “‘The Monster’:Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate.” Last modified May 5, 2016. https://www.wwno.org/post/monster-claiborne-avenue-and-after-interstate.

- Kaplan-Levenson, Laine. ”The Second Battle of New Orleans.” Last modified April 21,2016, https://www.wwno.org/post/second-battle-new-orleans.

- “Livable Claiborne Communities Study.” City of New Orleans. Last modified August 9, 2017. https://www.nola.gov/city/livable-claiborne-communities/.

- Reckdhal, Katy.“A Divided Neighborhood Comes Together under an Elevated Expressway.” Last modified August 20, 2018. https://nextcity.org/features/view/a-divided-neighborhood-comes-together-under-an-elevated-expressway.

- “The Interstate Highway System.” History.com. Last modified August 21, 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/us-states/interstate-highway-system

- “Tree Salvage Work Started,” The Times-Picayune, (New Orleans, LA), Feb. 10, 1966.

- Thruelsen, Richard. 1956. “Coast to Coast Without a Stoplight.” Saturday Evening Post 229 (16): 23–65. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=19962635&site=eds-live.

- Untitled video, Claiborne Avenue History Project, https://claiborneavenue.wordpress.com/.

- Weingroff, Richard F. “The Battle of New Orleans-Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310).” Department of Transportation. Last modified June 27, 2017. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm.

Primary Sources:

- Henry Ford II’s address in New Orleans expressing his opinions on the highway system as a must for the American Society.

Ford II, Henry. 1966. “The Highway System.” Vital Speeches of the Day 32 (22): 690. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9868021&site=eds-live.

The excerpt is Henry Ford II’s address in New Orleans at the club meeting of Young Men’s Business Club of Greater New Orleans on July 21, 1966. The reason why I want to use this is because Henry Ford II, the son of the automotive tycoon Henry Ford, believed that the construction of highways was “a partnership between government and industry” which was certainly the case here, however, I would specifically like to address the purpose of this partnership which was to only benefit the automotive industry and its dependent industries; in brief, use this source to express disagreement, possibly, at the beginning of the paper after stating my thesis statement. Also to express the delight of the automotive industry upon the passage of the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act. The speech comes from a timeframe when the Vieux Carre struggle against highway construction was in full speed.

2. An article from magazine in which the author expresses with great delight the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and what could be the positive consequences of the legislation.

Thruelsen, Richard. 1956. “Coast to Coast Without a Stoplight.” Saturday Evening Post 229 (16): 23–65. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=19962635&site=eds-live.

The excerpt is an article from the magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, in which the author expresses with great delight the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The excerpt is especially useful in illustrating the fact that only a few people would have thought about the consequences of highway construction especially on the minority community who suffered the most. I would like to use this source to illustrate the viewpoints of a popular magazine and pro-highway and how they received the legislation.

3. A photograph showing Claiborne Avenue before I-10 Expressway was constructed.

Davis, Joseph. North Claiborne Ave. 1968. Photograph. New Orleans Public Library. http://nutrias.org/photos/streets/streets_Claiborne_N_04.jpg

This is a photograph from 1968 that depicts Claiborne Avenue before Interstate 10 was constructed on the site. I would like to use this image in my paper to show how the street once looked. It would be interesting to look for an image of Claiborne Avenue today to show how the avenue looks today from the same aerial angle.

Secondary Sources:

- The source is from the Department of Transportation website that describes in detail the struggle against highway construction in the Vieux Carre neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Weingroff, Richard. “The Battles of New Orleans- Vieux Carre Riverfront Expressway (I-310).” US Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration. Accessed March 5, 2018.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/neworleans.cfm

This source gives a detailed account of the struggle against highway construction in the Vieux Carre neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana. The article comes from the Department of Transportation website that leaves researchers with a peace of mind regarding the reliability of this resource. I would like to use this article, specifically, to understand and contrast the struggle in Vieux Carre and Faubourg Treme neighborhoods in the mid to late 1960s at the beginning of the paper.

2. Brief outline of the history of Faubourg Treme neighborhood from its founding in 1812 to 1998.

“Faubourg Treme.” Tulane School of Architecture. Accessed March 5, 2018. http://architecture.tulane.edu/preservation-project/place/359

This page gives a brief outline of the history of Faubourg Treme neighborhood from its founding in 1812 to 1998. The history sheds light on the urban renewal projects that began the destruction of the historic neighborhood of Treme and the highway construction project in the 1960s specifically on Claiborne Avenue to construct Interstate-10, “an elevated expressway.” It also specifies The Concerned Citizens Neighborhood Improvement- Treme, an organization dedicated to preserve the remaining landmarks of the neighborhood. The article lists some sources that I can use and also to look into the organization that was formed to preserve the neighboring sites to illustrate how the memory of this avenue still lives on.

3. Claiborne Avenue today how the community is using the old space to see what the culture in Treme neighborhood once would have been.

Reckdahl, K. “A Divided Neighborhood Comes Together under an Elevated Expressway.” Next City, August 20, 2018.

I would like to use this resource towards the end of the paper to show how people still remember this avenue. It describes in detail how the community is using this space to remember and possibly revive the life of the neighborhood as it was before the construction of I-10 expressway. It has some photographs of the elevated expressway to show how people have decorated the columns of the expressway to remember how Claiborne Avenue once was. The photographs can possibly used in the image analysis assignment.

Image Analysis:

The image briefly summarizes the change in the landscape of my environmental injustice site North Claiborne Avenue from a site once having lined-up Oak Trees to its replacement with an elevated expressway- Interstate-10. The I-10 expressway was constructed through the Faubourg Treme neighborhood in New Orleans, an African American neighborhood which was sentimentally important for them because it was amongst the first areas in the United States where freed slaves had settled down. The image on the left is from 1968 and the other is from 2014. The consolidated image makes the argument of the highway construction in New Orleans being unfair to the minority community stronger which makes for a case of environmental injustice, depicted through the replacement of lined-up Oak trees and residential complexes with an elevated expressway and parking lots and yards for cars and trucks, respectively.

As aforementioned, the two images come from two different timelines, the one on the left comes from 1968 whose photographer was Joseph C. Davi and the one on the right is taken from Google Earth in 2014. Not much is known about the photographer Joseph C. Davi, but he has taken multiple images specifically of Claiborne Avenue. There is a strong possibility of Davi being on an assignment to take photographs of the site before its destruction.

The consolidated image has a deeper meaning than just simply a replacement of trees with a highway. The construction of the highway in New Orleans was unjust to the minority African American community; here, the focal points of the two images, the contrast in colors of the images, spatial relationships and sizes of elements convey the meaning effectively. Initially, the highway- Riverfront Expressway was proposed to cut through the Vieux Carre neighborhood, a predominantly white neighborhood of New Orleans, whose earliest white residents used their old money and influence in the government to successfully stop the highway construction.

The consolidated image has multiple focal points. However upon breaking the image up into two, the individual images have their own focal points. The focal point for image on the left is the lined-up Oak trees that stand out for two reasons one, it covers just more than half the length of the image and second, the lined-up trees are located in an urban environment which is not a common occurrence in every city. Here, the site of the lined-up trees was a neutral ground between residential complexes and the commercial complexes where once many African American businesses operated. As a result of the highway, many of these businesses either moved out or went out of business.

In comparison to the image on the right, the replacement of the trees with an elevated expressway that runs almost the entire length of the image depicts the enormous size of the highway and its importance to the government and corporations. The corporations greatly benefitted from the construction of highways because more highways with little to no public transportation meant more people would rely on cars as a mode of transportation which would make more people buy cars. Furthermore, it conveys the idea of the federal government valuing the highways more than the livelihoods of the minority African-American community.

The next element that draws attention in the image is the replacement of houses by parking lots and yards for cars and trucks. This depicts a loss in the livelihood of the historic neighborhood. The last element that draws attention is the contrast in color of the images and the serenity of the area. The image on the left comes from a timeframe post the invention of color photography, but this image is a black and white image. Perhaps, it was used to evoke a feeling of sorrow for the destruction of the neighborhood. While the image on the right, is a modern day color image, but it’s dominated by the color of the highway- grey which is a dull color that reflects a loss in the livelihood of the neighborhood.

In the end, upon combining the differences in elements of the images such as lined-up trees, residential complexes, elevated expressway and the parking lots and yards has one meaning. The highway construction in New Orleans was unjust to the minority African American community which the images depict effectively. Furthermore, it is important to note that the lined-up trees is perhaps a reflection of the enlightenment movement in Europe whose ideas were to be rational, logical and to be able to think independently. The significance of this movement is the fact that its ideas influenced the constitution of this country. Consequently, the highway construction is not only the loss of African Americans but also to the entire nation as a whole.

Image URL: http://architecture.tulane.edu/preservation-project/timeline-entry/1435

Data Analysis:

The construction of Interstate-10 through the Faubourg Treme, an African American neighborhood, New Orleans had an adverse effect on both the communities because the Faubourg Treme neighborhood and Vieux Carre neighborhood are situated right next to each other. As a result of this, there is not a significant difference in the environmental statistics of both the neighborhoods. The traffic proximity percentiles of both the neighborhoods: Faubourg Treme- 94 and Vieux Carre 85- are not across the opposite spectrum instead illustrate both the neighborhoods have come in close proximity to traffic as the result of the highway. Both neighborhoods being close to the highway are exposed to pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide. All these pollutants are toxic, increase the risk of chronic diseases related to the heart and lungs and increase the risk of acid rain. The NATA (The National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment) Respiratory and Cancer risk is an interesting contrast, the NATA Cancer risk percentile is higher in Vieux Carre in 90-95 percentile compared to 80-90 percentile in Treme which should have been the opposite considering Treme’s closer proximity to traffic and the resulting pollutants from the vehicles. Despite the counterintuitive number, the NATA Cancer risk is a great illustration of how both the neighborhoods are affected by the highway considering the similarities in number.

Another important aspect of this event to note is the timeline of the construction- 1968, this is a period just post the passage of the civil rights legislation and suburbanization is in full swing. The effect of suburbanization is reflected in the demographic statistics of the city post 1960 when the population begins to decline and there were more African Americans and Hispanics than the whites. In 1960, the population of New Orleans reached its peak to precisely 627,525 residents whose demographic composition was 62.56% white, 37.21% African Americans and 0.23% others. Upon moving to 1980 a period post the rapid suburbanization, the white population shrinks from a dominant 62.56% in 1960 to 42.51% in 1980 and the African Americans composition grew to 55.27% in 1980, up from 37.21% in 1960. The shift in numbers

The demographic statistics is an illustration of the rapid decline in the white population whose only explanation is suburbanization because it was a movement of the white population out of the cities into newly constructed suburban areas that had new infrastructure built specifically to make people dependent on cars. This led to the decrease in the overall population of New Orleans from 627,525 residents in 1960 down to 557,515 in 1980. The significance in the decline of the population is the movement of the majority white population out of the city and by 1980 the white population accounted for 42.51%, no longer being the majority population of the city.

The new infrastructure built post the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 made the masses dependent on cars and highways played an important role when there was nationwide suburbanization. Highways connected the suburbs to the cities which people could use to get to work or travel to the city for the purpose of leisure. Moreover, highways cutting through cities made it possible to get in and out of the city faster which is important because the number of cars on the road would only have made the traffic worse considering the roads within the city which were not as wide as the highways. However, it came at the cost of the livelihoods of the African Americans in Treme.

Demographic Statistics Source: https://daisi.datacenterresearch.org/Population/Historical-Population-By-Race-Over-300-Years/34pm-mf8u

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

For my video essay, I present how the Interstate-10 that was built on North Claiborne Avenue in Faubourg Treme, an African American neighborhood, in New Orleans, was not only unjust to the Treme neighborhood, but affected the Vieux Carre neighborhood unequally, a white neighborhood right next to the Treme neighborhood. In the video, I map not only Interstate-10, but also the Riverfront Expressway that was proposed to be built through Vieux Carre and was never built. Furthermore, I highlight how one organization CAHP (Claiborne Avenue History Project) is taking an initiative to preserve what is left in the Treme neighborhood.