“If I Sign, They’ll Mine”: A Comparison Between Differing Native American Perspectives on Energy Extraction

by Lauren Maffia

Site Description:

Approximately 30% of the total amount of coal and oil in the United States rests in or near Indian Reservations. In Montana, the Crow Tribe depends on the coal industry for their survival, with most of their budget coming from the Absaloka Mine. On the contrary, The Sioux Tribe of North/South Dakota oppose of an oil pipeline that was built parallel to their land, and across their main source of drinking water, the Dakota Access Pipeline. Two tribes carry very different views of the coal and oil industry, with one welcoming it to maintain their livelihood, and the other strongly opposing it to save their environment. After the coal industry was shut down, the workers were not given alternative employment opportunities. Why didn’t the government convert these industries to clean energy to save the peoples’ jobs? This is a conflict between most Native American Tribes in the U.S.; save and care for their environment, or put food on the table for their children? This is the internal battle Native Americans face as a result of oppression and confiscation of their resources by the U.S. government.s was happening.

Final Report:

Introduction

In Southern Montana, Wayne Moccasin of the Crow Tribe owns 2,000 acres of land, which he uses for ranching. Moccasin once ran cattle through a strip of prairie, land he inherited by his grandparents. The vast, open land goes on for the eyes to see, containing no trees, only grass along a bumpy landscape. They are a family of ranchers. Rumors of a prospective new coal mine have been circulating in the area. The location of this new mine would coincidentally lay on Moccasin’s land. The Moccasin family have indeed been involved in discussions regarding the leasing of their land for this mine. “If I sign, they’ll mine,” says Moccasin, strip mining his land will change the landscape of what he once knew. This revelation drew valid concerns over what will happen to their water and soil. However, collectively, they are not against the mining of coal. Poverty stricken, it all “comes down to money,” says Moccasin’s sister, Connie Moccasin. Desperation plays a key role in the Crow Tribe.[1]

Underneath this prairie lies coal only 10-12 feet below the surface. The Navajo Transitional Energy Company, Inc. (NTEC) has bought out assets from Cloud Peak Energy Resources LLC, which set its eyes on this land to mine for 22 million tons of coal per year. The prospective coal mine, which has been appointed as Big Metal, would be one of the largest to be built in the world. The land is owned primarily by Moccasin.

After years of oppression from the United States government, Native American Tribes were pushed onto reservations, where they reside today.[2] A majority of these reservations contain coal beneath the soil, with coal on reservations taking up almost 30% of the total coal reserves in the United States.[3] Coal mining strips the land, causes soil erosion, emits dangerous chemicals into the atmosphere and pollutes nearby waterways.

Similarly, these reservations also contain 20% of oil reserves in the U.S.[4] Oil pipelines are the cleanest and most efficient way to transport oil. They are also the most prone to leaks that pollute the soil and waterways. These reserves have caught the eye of energy companies for years, with most tribes turning them away. The environment is something Native American’s hold dear.

This essay will be evaluating two tribes with opposing views on energy extraction. The Crow Tribe of Montana, who heavily depend on the Absaloka Coal Mine for their annual budget and income, and The Sioux Tribe of North Dakota, who have been in a long battle against the Dakota Access Pipeline, which was built parallel to their land. These topics have been spoken of separately, but not compared with one another. Tribes across the United States have differing views on coal and oil. Some welcome it with open arms while others strongly resist it. These Native American tribes should not have to make this difficult decision of virtue vs. survival. Why must the very tribes who hold the environment as sacred have to choose to desecrate it in order to make a living? The Crow Tribe and The Sioux Tribe are just two examples of this.

As someone descended from the Manahoac Tribe, I find these differing opinions striking and warrants a closer look at these two divergent tribes. The virtues on the environment by my ancestor, Mary Evaline Bedford Haywood of the Manahoac Tribe, have been passed down through generations in my family. I have been taught that the environment should be kept in balance and humans should have a spiritual symbiotic relationship with the land and animals, utilizing every form and part of the resources available to them. The Crow and Sioux tribes are no different.

Energy Extraction

Humans have been extracting sources of energy from the Earth for centuries. Coal and oil being the most prominent and abundant sources found in the United States. Many of these coal and oil reserves lie on Native American soil. As a result of years of war and oppression from the U.S. government, the Native Americans were pushed onto reservations where resources are limited.[5]

As mentioned, Native lands contain 30% of the total coal reserves and 20% of total oil reserves in the United States.[6] Utilizing these resources would provide economic stability for these tribes. However, this would be in direct conflict with the fact that Native Americans hold the environment as sacred. The extraction process of coal and oil is very destructive to the land and environment so many tribes are apprehensive to take advantage of this opportunity. Other tribes, on the other hand, are left with no choice but to mine for coal and drill for oil as a means of survival, The Crow Tribe being just one example.

The coal industry is one of the oldest forms of energy and has been a main source of heat and electricity for centuries. Coal is a combustible fossil fuel; mining emits various hazardous chemicals such as methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and leaking mercury and other heavy metals into the nearby soil. Coal mining strips the land of its natural vegetation, the trees and grass, and utilizes the use of explosives to strip the soil and locate the coal beneath the surface. Mining for coal can cause adverse health effects, such as black lung.[7]

In recent years, the coal industry has taken a strong decline in production. This is due in large part to the environmental impacts and made worse by large corporations. Coal mines that were once owned by individual mine owners were bought out by large companies and turned into an entirely different industry on the inside. Doug Epling, who has been in the coal industry for 40-50 years and operated two mines in West Virginia, stated that large corporations would buy out a number of mines, accumulate debt from the previous owners and businesses, file for bankruptcy, and then leave the environmental cleanup to the government and taxpayers. By filing for bankruptcy, they deprive the workers of their lifetime benefits and retirement. These large corporations are able to get away with this in accordance with the bankruptcy law. According to this law, half of the accumulated debt will be forgiven when filing for bankruptcy. Using these new hedge funds, the corporation will form two other companies; one union and one non-union, and pass all liability onto one of those companies, thus freeing the parent company of accountability.[8]

According to Epling, the “Obama Administration delt a death [blow] to coal mining.”[9] When various coal mines began to be shut down under the Obama Administration, many coal miners lost their jobs with no compensation. This would not exclude the countless Native American tribes who depend on coal mining as a main source of income. The loss of financial compensation left these miners desperate and unemployed.

This interview with my uncle, Doug Epling, who has been in the coal industry for 40-50 years, gives insight into what has occurred to the industry in recent years. He also mentions and clarifies our Native American heritage and how he sympathizes with them.

Oil, like coal, is used as a source of electricity, and a cheaper option than most energy sources. Oil is drilled using the method of fracking, where water, chemicals and sand are injected into wells and results in fractures occurring to the surrounding rock, allowing for natural gas to be pushed outward. In doing so, any oil reserves in the rock will be pushed out as well. This method of oil drilling can be detrimental to the environment and water ways, leaking oil, soiled water, and chemicals used in the fracking process.[10]

The oil that is drilled can then be transported using oil pipelines. Oil pipelines are considered the safest way to transport oil by minimizing the risk of explosion, however they do pose a risk. Leaks occur multiple times a year, polluting the soil and nearby waterways with crude oil. Severe oil spills can harm the environment even further, potentially causing millions of dollars in damages and years to clean up the damage to the land and waterways.

The Crow Tribe of Montana

The Crow Tribe, also known as “Apsaalooke,” reside on what is one of the country’s largest reservations, which spans over 2.2 million-acres in southern Montana. This tribe is abundant with Native people, containing approximately 13,000 members, 7,900 of which reside on the reservation.[11] Despite having a large amount of people living on the reservation, their unemployment rate is about 25-50%.[12] In 2017, 1,000 of its 1,300 employees were laid off.[13] Their casino, which would have been vital for them, was shut down due to gaming violations, leaving them with no viable option for income but coal. The former Chairman of the Crow Tribe, Darrin Old Coyote, believes that alleviating poverty is of the upmost importance and has stated that “when it comes to coal, here at Crow you’re not going to have controversy.”[14]

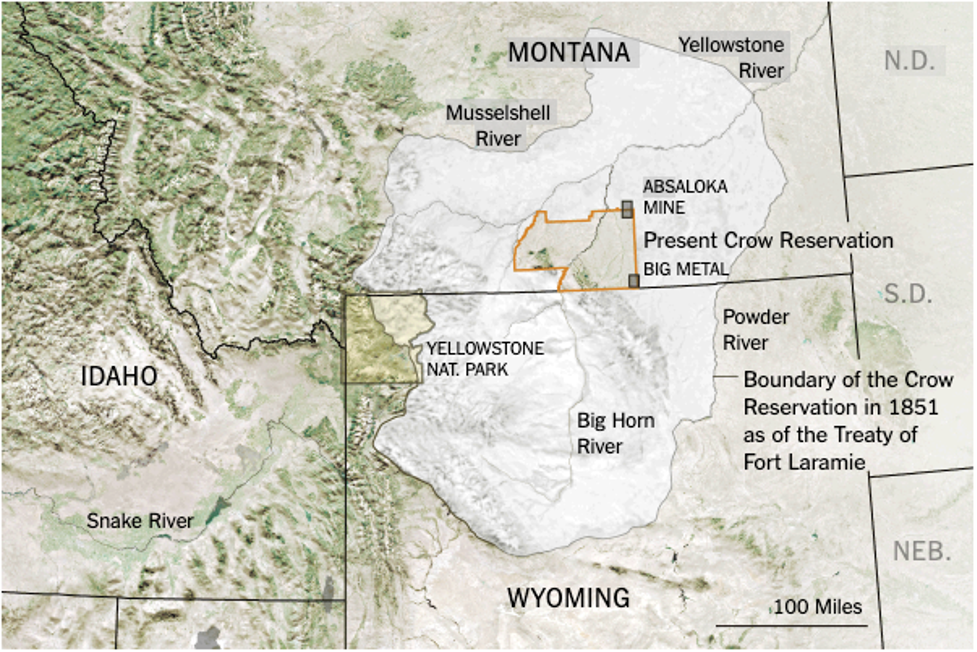

Already established in Montana is the Absaloka Mine. The Crow Tribe receives nearly half of their annual budget, around $13-15 million per year, by leasing their coal to this mine.[15] It’s conveniently located right on the border of the Crow reservation, as shown in figure 2 below. The Absaloka Mine is owned and operated by Westmoreland Absaloka Mining LLC and produces over 7.5 million tons of coal to be shipped off to its customers.[16]

A major issue that arose from the Absaloka mine occurred in 2019. While excavating a survey to expand the mine, a coal contracting company destroyed an ancient 2,000-year-old bison kill site. The bison kill site had ancient Native American artifacts lying within it, ranging from arrows to bison bones. It was determined to be the largest bison kill site in history, with Native Americans from many tribes using this site to hunt for bison many years before the Crow even resided there and was considered to be a national historical site.

The contractors were aware of this site and had an arrangement with the Crow tribe to avoid it during mining. However, a corrupt member of the Crow tribe’s cultural officials oversaw the excavation and allowed the contractors to use a backhoe to dig the area for coal. The damage this backhoe cost is the equivalent of $10.4 million, and enough bones and artifacts were dug up in the process to fill over 300 dump trucks. Burton Pretty On Top, a tribal advisor and spiritual leader, has stated “[This site] was a shrine or temple to us, we wanted to preserve the whole area … No amount of money in the world is enough to replace what has been lost here. The spirituality of our people has been broken.” [17]

In 2013, the Crow Tribe signed a contract to lease up to 1.4 billion tons of coal with Cloud Peak Energy Resources LLC to mine the reservation, which would make the coal mine one of the largest in the world, appointing it Big Metal Mine. This coal would be exported internationally to countries such as China and Vietnam. Cloud Peak Energy Resources LLC filed for bankruptcy in 2019, and in October of that year, Navajo Transitional Energy Company, Inc bought nearly all assets from Cloud Peak, including the prospective mine on the Crow reservation. To this day, the mine has not been built due to various legal issues, including apprehension from the Moccasin family and other Native American tribes. However, Big Metal Mine would bring in a lot of money for the tribe, as well as provide jobs.

Despite all the risks of operating a coal mine on their land, the Crow Tribe are still adamant on allowing and leasing its land and coal for companies to mine. The loss of the coal mine would result in a significant impact on revenue in the tribe. Widespread poverty in the Crow Tribe has placed a chokehold on their ability to find less destructive options for income. Consequently, coal, an industry currently on the decline, is now heavily depended upon by the Crow for its very survival.[18]

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North/South Dakota

The Great Sioux Nation consists of seven tribes. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is one of them, located on the border of North and South Dakota. They reside on a reservation consisting of around 1.4 million acres, with 10,859 members, 6,171 living on the reservation.[19] In 1868, a treaty between the Great Sioux Nation and the U.S. government titled the Treaty of Fort Laramie decided the borders of the nation and gave them total sovereignty of their land.[20]

Even while facing a nearly 80% unemployment rate, the Standing Rock Sioux still refuse to destroy their land by allowing mining or drilling to take place. Instead, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe run two casinos and encourage tourists to come visit its many rivers and creeks as well, where camping, hiking, and boating are the main attractions. Although the Sioux allow tourism, it doesn’t mean they feel that their land can be disrespected. The Sioux are so utterly in opposition to energy extraction and in accordance with their beliefs that they refuse to accept any money from the U.S. government. The total amount owed to the Sioux for prior annexation of some of their land, which violated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, is an astonishing 1.3 billion dollars.[21]

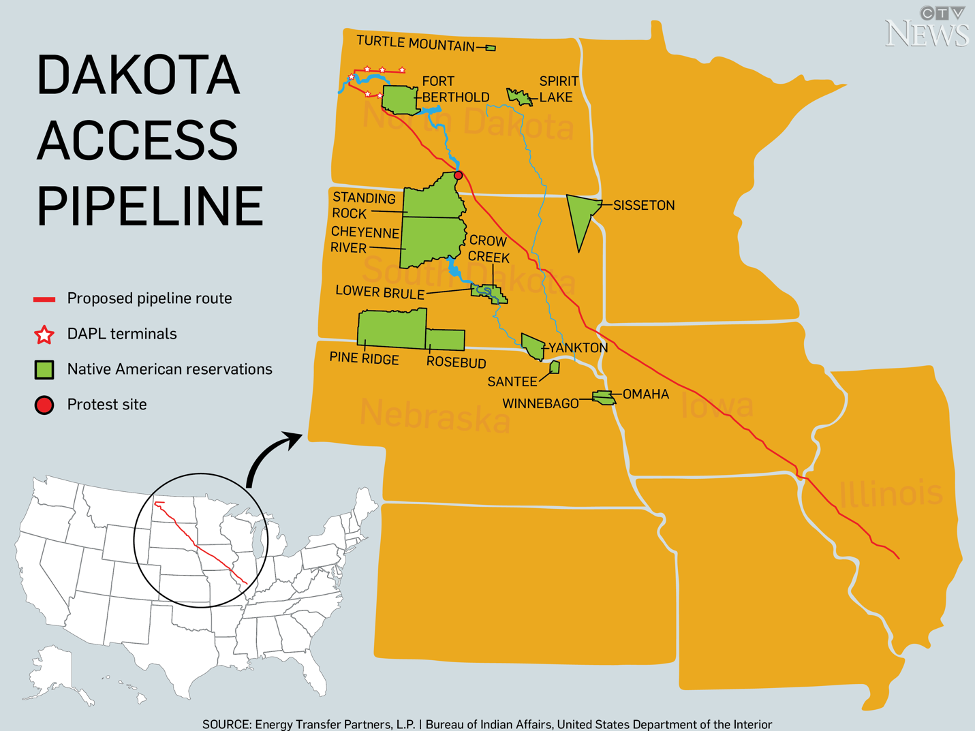

In 2016, Energy Transfer Partners announced its plans to build the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which would run through North and South Dakota to Illinois. The pipeline was meant to mitigate the amount of oil transported through North Dakota on freight trains. However, DAPL’s path runs right alongside the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s reservation, and cuts underneath their main drinking water source, Lake Oahe, potentially threatening massive pollution to occur to their drinking water. Although the pipeline does not cross reservation territory, the land it does cross is land the U.S. government illegally took from the Sioux.[22] Thus, the path also contains cultural and sacred sites, including an ancient burial ground sacred to many of the Sioux tribes. During the construction of the pipeline, around 380 of these sites were destroyed.[23]

Tahiat Mahboob and Phil Martin, “Dakota Access Pipeline Explained: What You Need to Know,” CTVNews (CTV News, November 10, 2016), https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/dakota-access-pipeline-explained-what-you-need-to-know-1.3143020.

Another route was initially proposed in a different area, north of Bismark, North Dakota, which is a largely non-indigenous population. Yet due to concerns over possible water contamination and protests rejecting the pipeline, it was re-routed to the route it is today. This raises the possibility of environmental racism; however, Energy Transfer Partners denies this route was ever a consideration due to its inconvenient location and the impossibility of placing the pipeline 500 feet or more apart from residential homes.[24]

This deep routed anger of injustice prompted protests to break out on the reservation. Members of various tribes across the nation came to North Dakota to aid in these protests. The members of the Sioux formed a group who called themselves the water protectors, using the phrase “Mni Waconi,” the Lakota translation for water is life. During these protests, the protestors faced mass police brutality. Over the course of many weeks of protests, officers arrested more than 750 people, attacked the protestors with pepper spray, rubber bullets, and sound cannons.[25] After being arrested, protestors faced mistreatment from the officers, being forcibly strip searched and kept in cages that held up to 25 people each.[26]

Due to these environmental concerns and protests, the Obama Administration halted construction and proposed the idea to reroute the pipeline. However, when the Trump Administration took over, Donald Trump signed an executive order allowing the pipeline to finish construction, ultimately reversing the progress the Sioux Nation had made.[27]

The Sioux Nation hold their land in high regard. There have been at least 5 leaks since the completion of the Dakota Access Pipeline. While these leaks were relatively small, one leaking around 20 gallons in North Dakota and another seeping as much as 168 gallons of oil in Illinois, Energy Transfer Partners stands by the pipeline stating that it is still the safest and most environmentally friendly way to transport oil.[28]

As of July 6, 2020, the Dakota Access Pipeline was ordered to shut down as a result of an inadequate environmental assessment done by the Army Corps of Engineers before construction. Since then, the Army Corps have filed an intent to do another environmental assessment. While this is certainly a win for the Sioux Nation, it is just the beginning of many years of hard work protesting against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Differing Voices

In Montana, the Crow Tribe depends on the coal industry for their survival, with most of their budget coming from the Absaloka Mine. On the contrary, The Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota oppose of an oil pipeline that was built parallel to their land, and across their main source of drinking water, the Dakota Access Pipeline. Two tribes carry very different views of the coal and oil industry, with one welcoming it to maintain their livelihood, and the other strongly opposing it to save their environment.

The Crow Tribe still consider their land as a source of pride, but a stroke of bad luck forced them to make the difficult decision to mine their land. The incident at the Absaloka Mine proved the passion the Crow people have for their land and sacred sites. The need for money to buy food and maintain a roof over their heads is the main priority guiding their decisions in the Crow Tribe.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe run two casinos on their land alongside various lodges and resorts. They encourage tourism and utilize that for income. The many rivers and creeks surrounding their land are the perfect place for camping and swimming. With their land enabling them to take part in tourism, they do not need to make money off of energy extraction. They also have the option to fight for their land against energy extraction companies, such as Energy Transfer Partners and the Dakota Access Pipeline. Location seems to play a key role, especially for resources.

A conflict between most Native American tribes in the U.S. seems to be to save their environment or put food on the table for their children. This is the internal battle Native Americans face as a result of oppression and confiscation of their resources by the U.S. government. The Crow Tribe of Montana and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota are just two of the many Native American tribes facing these difficult decisions today, when there should be no need to.

Endnotes:

[1] This paragraph is credited to Tripp Baltz, “Mining Tribal Land Weighs on Crow Family as Cost of Prosperity,” ed. Bernie Kohn and Chuck McCutcheon, Bloomberg Law, March 12, 2020, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/mining-tribal-land-weighs-on-crow-family-as-cost-of-prosperity.

[2] Terry Anderson. “The Native American Coal War,” Forbes online, May 18, 2016.

[3] Statistics credited to Julie Turkewitz. “Tribes That Live Off Coal Hold Tight to Trump’s Promises,” The New York Times online, April 1, 2017.

[4] Statistics credited to Julie Turkewitz. “Tribes That Live Off Coal Hold Tight to Trump’s Promises,” The New York Times online, April 1, 2017.

[5] Terry Anderson. “The Native American Coal War,” Forbes online, May 18, 2016.

[6] Statistics credited to Julie Turkewitz. “Tribes That Live Off Coal Hold Tight to Trump’s Promises,” The New York Times online, April 1, 2017.

[7] This paragraph credited to “U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – Independent Statistics and Analysis,” Coal and the environment – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), last updated December 1, 2020, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/coal/coal-and-the-environment.php and Raja Venkat Ramani and M. Albert Evans, “Coal Mining,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., July 7, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/technology/coal-mining.

[8] This paragraph is credited to Doug Epling in discussion with the author, October 29, 2020, https://ejhistory.com/oral-interview-video-essay-image-analysis-lm/.

[9] Doug Epling in discussion with the author, October 29, 2020, https://ejhistory.com/oral-interview-video-essay-image-analysis-lm/.

[10] This paragraph credited to Lukasz R., “History of Oil – A Timeline of the Modern Oil Industry,” EKT Interactive, accessed December 13, 2020, https://ektinteractive.com/history-of-oil/.

[11] This paragraph is credited to John T Doyle et al., “Challenges and Opportunities for Tribal Waters: Addressing Disparities in Safe Public Drinking Water on the Crow Reservation in Montana, USA,” History Studies International Journal of History 10, no. 7 (March 21, 2018): pp. 241-264, https://doi.org/10.9737/hist.2018.658.

[12] Amy Martin, Why Montana’s Crow Tribe Turns To Coal As Others Turn Away, read by author (Inside Energy, 2015) 4 min., 47 sec. https://soundcloud.com/inside-energy/why-montanas-crow-tribe-turns-to-coal-as-others-turn-away. During the duration of writing this paper, Inside Energy’s website was offline as of December 15, 2020. Some resources may not be available, but their audio recordings of articles are available on SoundCloud.

[13] Julie Turkewitz. “Tribes That Live Off Coal Hold Tight to Trump’s Promises,” The New York Times online, April 1, 2017.

[14] Quote and following sentence credited to Amy Martin, Why Montana’s Crow Tribe Turns To Coal As Others Turn Away, read by author (Inside Energy, 2015) 4 min., 47 sec. https://soundcloud.com/inside-energy/why-montanas-crow-tribe-turns-to-coal-as-others-turn-away. During the duration of writing this paper, Inside Energy’s website was offline as of December 15, 2020. Some resources may not be available, but their audio recordings of articles are available on SoundCloud.

[15] Matthew Brown. “Crow tribe: Noted bison kill site desecrated by coal mine,” The Santa Fe New Mexican online, November 9, 2019, https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/crow-tribe-noted-bison-kill-site-desecrated-by-coal-mine/article_a0f4c59f-4b1b-56fb-8ddd-1deaf7b8e5cc.html.

[16] “Westmoreland Absaloka Mining LLC,” Westmoreland, accessed December 14, 2020, https://westmoreland.com/location/absaloka-mine-montana/

[17] This paragraph is credited to Matthew Brown. “Crow tribe: Noted bison kill site desecrated by coal mine,” The Santa Fe New Mexican online, November 9, 2019, https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/crow-tribe-noted-bison-kill-site-desecrated-by-coal-mine/article_a0f4c59f-4b1b-56fb-8ddd-1deaf7b8e5cc.html.

[18] This paragraph is credited to Tripp Baltz, “Mining Tribal Land Weighs on Crow Family as Cost of Prosperity,” ed. Bernie Kohn and Chuck McCutcheon, Bloomberg Law, March 12, 2020, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/mining-tribal-land-weighs-on-crow-family-as-cost-of-prosperity.

[19] “Environmental Profile,” Standing Rock, accessed December 14, 2020, https://www.standingrock.org/content/environmental-profile.

[20] “Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868),” accessed December 14, 2020, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=42&page=transcript

[21] Unemployment rate and amount owed to the Sioux credited to “Why the Sioux Are Refusing $1.3 Billion,” Public Broadcasting Service online, August 24, 2011, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/north_america-july-dec11-blackhills_08-23.

[22] “Why the Sioux Are Refusing $1.3 Billion,” Public Broadcasting Service online, August 24, 2011, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/north_america-july-dec11-blackhills_08-23.

[23] Edward John, “Report and Statement from Chief Edward John Expert Member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Firsthand observations of conditions surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Unpublished Report, North Dakota, USA, November 1, 2016, 3, available online at https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/secure.notion-static.com/bb92c561-ac31-4f90-9caa-7b6d5ebed45f/Report-ChiefEdwardJohn-DAPL2016.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAT73L2G45O3KS52Y5%2F20201215%2Fus-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20201215T152425Z&X-Amz-Expires=86400&X-Amz-Signature=baad8e285a5cfafb4cc68ad086b1506ea398546b665c6ec523b5321117c6a8ee&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&response-content-disposition=filename %3D”Report-ChiefEdwardJohn-DAPL2016.pdf” Accessed November 16, 2020.

[24] Catherine Thorbecke, “Why a Previously Proposed Route for the Dakota Access Pipeline Was Rejected,” ABC News, November 3, 2016, https://abcnews.go.com/US/previously-proposed-route-dakota-access-pipeline-rejected/story?id=43274356.

[25] “Native American´s Sioux against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), USA,” Environmental Justice Atlas, last updated July 7, 2020, https://ejatlas.org/conflict/dakota-access-pipeline.

[26] Edward John, “Report and Statement from Chief Edward John Expert Member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Firsthand observations of conditions surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Unpublished Report, North Dakota, USA, November 1, 2016, 4, available online at https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/secure.notion-static.com/bb92c561-ac31-4f90-9caa-7b6d5ebed45f/Report-ChiefEdwardJohn-DAPL2016.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAT73L2G45O3KS52Y5%2F20201215%2Fus-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20201215T152425Z&X-Amz-Expires=86400&X-Amz-Signature=baad8e285a5cfafb4cc68ad086b1506ea398546b665c6ec523b5321117c6a8ee&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&response-content-disposition=filename %3D”Report-ChiefEdwardJohn-DAPL2016.pdf” Accessed November 16, 2020.

[27] Source: AP, “Trump Signs Order Reviving Controversial Pipeline Projects – Video,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, January 24, 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/video/2017/jan/24/dakota-access-keystone-xl-pipelines-order-video.

[28]This paragraph is credited to Producer: Ethan Oberman | Hosted by Todd Zwillich, “Dakota Access Pipeline Leaks Start to Add Up,” WNYC Studios, January 11, 2018,https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/takeaway/segments/across-country-smaller-pipeline-leaks-start-add.

Primary Sources:

Source 1: Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)

Location: Our Documents Initiative

This is a transcript of the treaty between the Sioux and the United States in 1868. This will help me determine where the U.S. is violating treaty law.

Source 2: The New York Times Article “North Dakota Oil Pipeline Battle: Who’s Fighting and Why”

Location: The New York Times

This article not only details the events that occurred at the protests at Standing Rock, but also looks at it from other perspectives, including farmers.

Source 3: Report and Statement from Chief Edward John, Expert Member of the

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues: “Firsthand observations of conditions surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline”

Location: United Nations

This report details statements from the voices of those protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, as well as getting statements from the officers on duty who actively arrested protestors and guarded the pipeline’s construction.

Primary Source Analysis:

Source 1:

The Treaty of Fort Laramie is a peace agreement between the tribes of the Sioux Nation and the United States of America. In the treaty, it also goes over which parts of the land solely belong to the Sioux and that in order for anyone to enter the territory, they must first get permission from the tribe. The articles in this treaty give the Sioux Tribe the rights to their land. This source suggests that the land was a large part of the Native Americans’ lifestyle and incredibly important to them.

In article II of this treaty it states, “The United States agrees that the following district of country… and in addition thereto, all existing reservations of the east back of said river, shall be and the same is, set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians herein named…” This quote lists the exact areas that belong to the Sioux Tribe that belong to them, and that this land will remain undisturbed by anyone other than the Natives of that land. Article VI states “If any individual belonging to said tribes of Indians… shall desire to commence farming, he shall have the privilege to select… a tract of land within said reservation…” This gives the Native Americans the right to choose their own piece of land for agriculture, only needing to receive a certificate to grow on that land. The fact that this statement is in this treaty proves that agriculture is a large part of their society. Many other articles state protocols for agricultural purposes as well. Article XVI explains how people need to receive permission by the tribe in order to pass or live on the land, as well as any military positions located on that land will be abandoned. “…and also stipulates and agrees that no white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the same; or without the consent of the Indians, first had and obtained, to pass through the same; and it is further agreed by the United States… the military posts now established in the territory in this article named shall be abandoned…”

Source 2:

This article written by Jack Healy goes over a short timeline of events from the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. It also goes over others who are in opposition of the pipeline and leaves the reader with the question, are pipelines are really as safe as corporations say they are? This article suggests that pipelines are more dangerous than they appear, given the large boom of them in the past century.

In his article, Healy mentions the various others who are in agreement with the Sioux Tribes. Veterans came out to protect the protestors as police began to use violent tactics against them. Healy mentions that various farmers have taken their cases to court to prevent the pipeline from crossing their farmland, however many have given approval of it. At this point in time, 2016, it was unclear if the pipeline was going to be finished. Healy also mentions other pipelines in the U.S. such as the Keystone XL and the Sandpiper who also received major backlash from residents and environmental groups. Two pipelines, one by Tesoro Logistics and another from Enbridge Energy have leaked over 800,000 gallons of oil into the lands and rivers near them, costing billions of dollars in cleanup. It is clear that pipelines have an uncertainty about them, the longer they are in the soil, the more at risk they are of leaking a great amount of oil.

Source 3:

Chief Edward John, who works for the United Nations focusing on Indigenous Issues went to the site of the protests at Standing Rock. He obtained testimonials from protestors as well as Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman David Archambault. John also got statements from senior law enforcement officials on site. John was able to obtain multiple viewpoints at the site of the protests and as someone who is an expert in this field, gave his opinion and recommendations for the U.S. government to take action. It is clear that at this point in time, police brutality was still in full force. Reading of the hardships and injustice the protestors faced for protesting peacefully proved that.

John compared his experiences on site to a “war-zone.” He accounts “on the bridge near the south camp I witnessed burned out vehicles stationed to prevent passage either

way. Large concrete blocks have also been laid across the bridge beyond the destroyed vehicles. Nearby I met officers in body armor, fully armed and in full camouflage gear.” One account from an “elder woman stated that she was holding her sacred bundle skyward in prayer and was suddenly forced to the ground, crying out as she watched her sacred bundle fall to the ground.” Sacred bundles are similar to bibles of the church to Native Americans. This was as a result of a clash between horse riders and the police officers on duty, where many were arrested. After being arrested, on multiple accounts, they were not informed on the reason they were being arrested and faced being “marked with numbers on their arms”, similar “to the branding of Jewish persons” during the holocaust. The law enforcement officers, however, deny that any form of injustice was placed upon those arrested, and instead “treated with respect, fed, clothed and their medical needs attended to.”

Secondary Sources:

EMMONS, GEORGE. “The Unseen Harm: U.S.-Indian Relations & Tribal Sovereignty.” Golden Gate University Law Review, vol. 48, no. 2, May 2018, pp. 185–206. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=129225287&site=ehost-live.

This academic journal article goes over the history of the U.S. disregarding treaties with Native Americans, including the Sioux Tribe.

This article will help me learn more information on what happened between the Sioux Tribes and the government during the process of the Dakota Access Pipeline. I found this one prominent because it was posted in a law journal. This will help me build a timeline of the legal issues. It also compares other sites of Native Americans vs. U.S. where treaties were disregarded, and will help me gain insight into how other tribes view, and experience, the same issues the Sioux faced.

Greenpeace Reports. Too Far Too Often: Energy Transfer Partners’ Corporate Behavior On Human Rights, Free Speech, and the Environment. 18 June 2018, http://www.greenpeace.org/usa/reports/too-far-too-often/.

This article goes into depth of the history of Energy Transfer Partners and the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In this article, Greenpeace Reports goes over safety concerns from the pipeline and how Energy Transfer Partners violated Native American rights. It goes into depth on the repeated injustices the Sioux faced, including being intimidated and silenced. This article will help me understand how this company was able to get away with building the pipeline in this area. It will give me insight into the minds of those in the oil industry, and how through strategic planning can maneuver plans in their desired direction.