Homes and Highways: Rupture and Resistance in Los Angeles’s West Adams Neighborhood

by Jordan Baldridge

Site Description:

The West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles was first populated by turn-of-the-century moguls: white men who had built fortunes in the city’s booming new industries. When what is now Mid City Los Angeles existed on the periphery of a very young city, they built Craftsman and Victorian mansions that defined the neighborhood’s image and status. In the late 1930’s, the neighborhood would become home to a Black middle and upper class that included prominent businesspeople and performers. The neighborhood, however, was cleaved down the middle in 1963 by the construction of Interstate-10. This project sets out to examine the origins of the decision to bulldoze a historic, famous, and wealthy Black community. Why, for example, was the freeway route plotted on this particular course? Was there resistance to the construction of the interstate? And, finally, what have been the long-term impacts of this dramatic change in the built environment? This project taps into a broader history of highway construction while analyzing factors of race, class, and power. Despite the prevailing narrative that urban renewal projects and sites of environmental injustice take advantage of poor neighborhoods lacking political power, West Adams provides a case study that disrupts these notions.

Final Report:

Langston Hughes landed in a Los Angeles of his own creation. The city he recounted following his 1946 visit exists today only as a refraction from a historical mirror, or as a mirage shimmering against the carcinogenic contemporary landscape. It existed at one point, and also did not exist at all. He wrote to the readers of the Chicago Defender that “the street-cars are crowded…and almost everybody has a little yard with a flower or two and a little spot of grass growing in it.”[1] This landscape did, at one time, exist. The postwar metropolis was economically booming but not overcrowded, a place where open space and urban bustle could coexist. However, any visitor to contemporary Los Angeles would know that the streetcars have since vanished and that the space he admired has been gobbled up by developments of every variety. His account also dabbled in the fantastical. “Race prejudice is nothing like it is in the South or Middle West…There is no dirty coal smoke in the air,” he declared to a nation familiar with hearing such myths about life in California. Both of these statements were beyond exaggerations. Los Angeles was a land as mired in racism as any other, and even Spanish colonial voyages referred to the region as “The Valley of Smoke,” likely because the region’s mountains create an inversion layer that naturally traps particulate matter in the air.[2]

Bursting forth in the middle of Langston Hughes’s account is his description of a neighborhood he calls “Blueberry Hill.” “Out on Blueberry Hill, that seems well on the road to being renamed Sugar Hill after Harlem’s upper section, there are the most beautiful Negro homes I have ever seen.”[3] Indeed, the enclave he described would go on to become known as Sugar Hill, the wealthiest section of a neighborhood in Central Los Angeles called West Adams. Hughes goes on to list the names of many prominent Black residents such as insurance mogul Norman O. Houston and actress Hattie McDaniel, both of whom lived in what was soon to become “Sugar Hill,” and marvels at the opulence of their homes. Considering the neighborhood’s national prominence as a place of residence for wealthy Black urbanites, Hughes’s fixation with West Adams Heights was no surprise.[4] In the great poet’s account, “Blueberry Hill” stands in as an alluring symbol for all that Black Americans could achieve in California’s land of unparalleled opportunity. Sugar Hill is metonym for all that is possible.

For a synopsis of this project on West Adams, see this video story (created by Jordan Baldridge)

In contemporary Los Angeles, West Adams remains the subject of local legend and urban lore, but it has come to occupy a different type of mythic space than it did for Langston Hughes. Now bisected by the Santa Monica Freeway, or Interstate 10, the public memory of the neighborhood’s past floats like a specter haunting Angeleno urban discourse. Despite the fact that it remains a thriving enclave in central L.A., many locals know the neighborhood as a site of rupture and displacement from when it was torn in half by the freeway’s arrival. Elegant craftsman homes remain but now appear out of place bordering the concrete ravine carved out by highway developers in the late 1950s. The houses’ genteel frames and large lots tell the story of a neighborhood forever changed and stand in direct tension with the vehicular fortress of the interstate. Many of the most impressive homes are gone forever.

West Adams, a neighborhood of celebrated architectural and social renown, is equally well known as a site of tension and resistance. In the 1940s, Black Sugar Hill residents defended their right to remain in the neighborhood by working to legally overturn racially restrictive covenants that sought to push them out. This conflict solidified West Adams as a trailblazing site of Black American fortitude and fearlessness, but the fruits of the victory were short-lived. When highway planners plotted the course of the Olympic Freeway through the heart of West Adams, residents fought back but were unable to deter the freeway’s progress. As Jennifer Mandel writes in her brilliant dissertation, “Making a Black Beverly Hills,” Black Angelenos “gained the legal protection to live in desirable areas, but they could not end racism, prevent white flight, or persuade white policymakers to respect the value of their communities.”[5]

This paper tells a social history that considers the tension between the determination and fortitude of West Adams’s Black community and the powerful forces of structural change that shape the urban environment. How, for example, does Sugar Hill residents’ successful fight against restrictive covenants inform our understanding of their resolute but unsuccessful fight against the arrival of the freeway? What were the origins of the decision to route the freeway through West Adams, and how did its eventual construction impact the neighborhood both socioeconomically and environmentally? Finally, how does West Adams’s history speak to broader discourses in urban and environmental history, especially those historiographies concerned with the fate of Black neighborhoods facing changes in the built environment? Sugar Hill residents’ successful and unprecedented legal battle against restrictive covenants demonstrates that West Adams was far from an easy target for highway planners. But, despite the neighborhood’s long history of organized resistance, the twin forces of highway boosterism and structural racism propelled the Olympic Freeway through West Adams, saddling the community with the dual burdens of worsening environmental conditions and increasing economic marginalization.

Few have considered in depth or detail the origins of the freeway’s arrival in West Adams. Most popular accounts of this history consider the construction of the interstate a foregone conclusion that tossed defenseless West Adams residents aside, and these narrations usually end with the arrival of the freeway without considering its impacts.[6] A few historians have noted the freeway’s construction in West Adams in their scholarly work, but none have comprehensively researched the context and implications of this history. Josh Sides briefly mentions the Olympic Freeway in his sweeping history of African Americans in Los Angeles, L.A. City Limits, but leaves the reader with little detail on the origins or impacts of the routing.[7] Jennifer Mandel comes closer to unlocking the total narrative in “Making a Black Beverly Hills,” by situating the freeway construction in the context of the neighborhood’s broader history.[8] She understands the freeway’s arrival as one of many sinister events that continued to force Black Angelenos to remake their sense of place and belonging in the city. In this paper, I will add to Mandel’s account by including a comprehensive look at the forces leading to the freeway’s arrival, by including a comparison of routing decisions in West Adams versus other neighborhoods, and by considering the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of the freeway on West Adams.

Other scholars have written about freeway construction, race, and resistance in ways that will help sharpen this essay’s analysis. In his article “Building a Better Houston,” Kyle Shelton details the fight of two different urban communities in Houston – one affluent and white, the other mostly poor and Black – against freeway construction in their neighborhoods. He analyses the rhetoric and tactics used by each group and argues that, while the outcome of each fight was determined by the racial and class statuses of the groups, both neighborhoods claimed “infrastructural citizenship” by turning their neighborhoods and streets into arenas of political struggle.[9] Shelton’s article is a model study in analyzing the tactics and outcomes of groups resisting highway construction and my work seeks to build upon the framework he presents.

Eric Avila has written extensively on the cultural history of freeways and two of his works crucially inform my project. In “L.A.’s Invisible Freeway Revolt,” he explores Boyle Heights residents’ resistance to the construction of freeways in their neighborhood, demonstrating that forms of artistic and creative resistance are worth documenting. He argues that, while Beverly Hills famously deterred the arrival of a proposed freeway, marginalized neighborhoods’ resistance still informs our understanding of urban history, even if that resistance does not ultimately stop construction.[10] Avila also notes in his book, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight, that Black neighborhoods were frequently targeted for clearance during urban redevelopment projects, oftentimes with the justification that their homes held no value to white residents or urban planners.[11] My analysis of West Adams will both benefit from and bolster Avila’s claims by exploring the origins of the decision to route the highway through a middle and upper class Black neighborhood.

The ensuing paper will begin by reviewing existing literature that has documented Sugar Hill residents’ legal fight against restrictive covenants, analyzing the ways this fight informs and sets the stage for the arrival of the highway. A contextual re-telling of this history is essential for writing a complete story about the arrival of the Olympic Freeway and will be supplemented with primary documents that provide additional context when applicable. Following a brief introduction about the broader context of highway construction, the rest of the paper will document and analyze the origins of, resistance to, and impacts of the Olympic Freeway’s routing through West Adams. The final section will draw connections between the freeway’s history and its presence as a dividing line in the contemporary urban landscape, exploring how Interstate-10 connects the urban past with the urban present.

Staking a Claim: The Battle Against Restrictive Covenants

The Edward James Brent House in Los Angeles’ Sugar Hill neighborhood

West Adams’s history dates back to the late 1800s, when the West Adams Heights section of the neighborhood – what would become Sugar Hill – was settled by white moguls who built stately Victorian and craftsman mansions. The Edward James Brent house, seen above, exemplifies the unique craftsman styles and opulent lots that could be found in the neighborhood. The rest of the area was filled with middle and upper middle-class homes, many built in craftsman or Spanish Revival styles. [12] Berkeley Square, a famous palm tree-lined private drive, boasted many of the most impressive residences in Los Angeles’s early history and housed many prominent Angelenos.[13]

After both the onset of the Great Depression and the expansion of upper-class enclaves like Beverly Hills, West Adams’s early white residents began leaving in favor of new neighborhoods. This offered an opportunity for middle and upper-class African Americans to buy into the area. Despite the continued prevalence of restrictive covenants – clauses in the deed of a property that prevented its sale to non-white residents – many Black Angelenos managed to purchase homes in the neighborhood.[14] Well before Langston Hughes’s visit in 1946, Sugar Hill became the center of Black elite social life in Los Angeles. Hattie McDaniel, the actress famous for her role in Gone with the Wind, threw parties and hosted entertainers such as Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Cab Calloway.[15] The elite neighborhood that had served as Los Angeles’s most coveted white residential district became synonymous with the Black upper class.

Black settlement in the neighborhood, although possible, was nonetheless met with vitriol from white residents. Black residents began buying houses in West Adams as early as 1935, but insurance mogul Norman O. Houston was the first to purchase a home in the heart of West Adams Heights.[16] Houston, the owner of one of the largest Black-owned businesses west of the Mississippi River, was hesitant to subject himself to racial hostility and at first decided to rent his house to a white tenant. He eventually moved into the home in 1941 and was followed by several more prominent African Americans. This demographic transition was received with hostility by members of the West Adams Improvement Association, a white homeowner group, who filed a lawsuit in the California Superior Court arguing that Black homeownership in the area violated existing restrictive covenants.[17]

Jennifer Mandel documents in “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills’” that Black West Adams Heights residents, led by Hattie McDaniel and famous singer Ethel Waters, were incredibly well-organized before and during the ensuing legal battle. Long before the threatening lawsuit arrived, West Adams residents were deeply involved in community organizing efforts, neighborhood business associations, and were almost all active members of the local NAACP and Urban League chapters. Many of them had waged campaigns aimed at integrating local businesses and advocated for greater access to city amenities and services for Black Angelenos. During the legal battle, Sugar Hill homeowners canvassed blocks, hosted meetings in their homes, and held press briefings. Additionally, they all risked their livelihoods and reputations by attaching themselves so publicly to the case and many hired lawyers of their own to defend themselves.[18]

When the case reached the California Supreme Court in 1946, Sugar Hill residents recruited NAACP attorney Loren Miller to lead their case. Miller, who had been fighting restrictive covenants in Los Angeles for years, went on to win the case in California’s highest court. The Sugar Hill case was monumental and was celebrated as such in the African American press nationwide. Newspapers in distant cities such as Cleveland, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Chicago covered major developments in the court case and rejoiced in the defendants’ victory.[19] The Sugar Hill decision prompted the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the Shelly vs. Kraemer case on restrictive covenants, in which Loren Miller went on to serve as chief defense alongside future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. The pair litigated successfully, and in 1948, restrictive covenants were deemed unenforceable nationwide.[20] West Adams residents had played a major role in building the movement that would eventually topple legally segregated housing in the United States.

By moving into the neighborhood and then tirelessly organizing – first in their neighborhood and eventually in the national spotlight – Black West Adams residents bent the urban legal landscape to accommodate their presence, turning a contested, de facto belonging into a permanent, de jure one. They displayed fearlessness, determination, and confidence in their own authority that enabled them to claim and defend their presence in a neighborhood that, at first, legally excluded them. Sugar Hill, already known nationwide, became even more famous and served as an inspirational symbol to African Americans around the country. In this sense, West Adams residents lived up to the aspirational image Langston Hughes painted of them following his 1946 visit. Sugar Hill was a place where racial barriers could be broken, Black humanity could be defended, and belonging could be claimed. The context of this exceptional story is crucial context when understanding the arrival of the highway, the community’s next existential threat.

Rise of the Highway: The Olympic Freeway and the Tides of Change

During the time Black West Adams residents worked to secure legal permanence in their neighborhood, the nation was turning a page and entering a new era. By 1946, the United States was bathing in the fortune and optimism of what would become the postwar era, a time where the country’s lone superpower status emerging from World War II fueled countless social and economic changes. Brewing in the midst of this epochal shift was the infrastructural development that would most singularly re-shape the American city: the continued expansion of the highway. While highway construction already had a half-century long history in the United States, the Federal Highway Act of 1944 provided significant federal funding for the expansion of highways in urban areas for the first time.[21] With the highways came optimism that vehicular transit would propel the country into the future, representing the best of modern civilization.[22]

While Los Angeles had, at one point, boasted the world’s largest electric rail transit system, the city, like the nation, was primed for a shift to automobility.[23] The private companies like Pacific Electric, who operated the famed Red Cars about which Langston Hughes pined in his 1946 account, were in deep financial trouble and their transportation could not compete with the speed and perceived convenience of the now-affordable automobile. Los Angeles had grown immensely in the decades preceding the war, with the city’s population nearly tripling between 1920 and 1940.[24] City and county officials were concerned about the state of local transportation infrastructure and its ability to accommodate the booming regional population. In their 1943 report, “Freeways for the Region,” the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors said regarding highway planning and construction, “the penalty for failure to act or for tardiness may be a dire tragedy.”[25] This sense of urgency is important to keep in mind when assessing the ways these plans would impact urban communities and their ability to negotiate with city and state officials. Freeways were not a trivial change in the urban landscape, they were a federally fueled solution to a dramatic and pressing local problem. These major tides of urban redevelopment would soon arrive in West Adams.

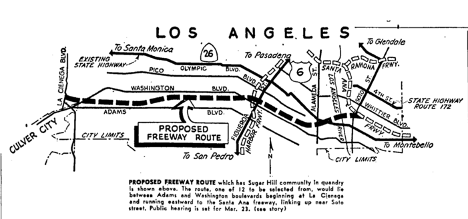

While Los Angeles would eventually build one of the nation’s most comprehensive and notorious freeway networks, in the 1950s the city lacked a highway traveling east-to-west across its terrain. A highway traveling laterally across the city was necessary for any of the other proposed routes to serve their purpose in relieving traffic and linking the region together. Early renderings of the plan for the regional freeway system, in fact, include as many as three such routes, named the Venice, Olympic, and Santa Monica parkways in the 1943 proposal.[26] These routes would link together the downtown business district, located on the right periphery of the above map, with the burgeoning westside, located from the center to the left edge of the map. By 1952, plans for the Venice and Olympic Parkway had been collapsed into one fully combined route, following the path of the Olympic Parkway as shown above.[27]

Many, including City Councilman Charles Navarro, who represented West Adams, knew that where there was smoke, there was fire. The local politician, understanding the forces his constituents were about to find themselves up against, questioned the need for the freeway in hopes that some alternative could be worked out. “Inasmuch as the project will work a great hardship on a tremendous number of home-owners…and in addition cost many millions of dollars…I urge that we exhaust all alternative measures before accepting the Olympic Freeway as the answer to the problem,” Navarro said.[29] Just a few months later, it was announced that the plans would, indeed, threaten West Adams. The below diagram, from the Sentinel, detailed the proposed route as it would cut through the neighborhood.[30]

To understand the origins of this routing decision, it is necessary to take a longer historical view of urban planning. In his research on the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights, Eric Avila proposes that the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s redlining of that neighborhood could have played a role in the decision to bulldoze sections of it to make way for highways.[31] We can draw a similar connection between West Adams and redlining, considering appraisers labeled every tract in the neighborhood either “yellow, C” for “definitely declining” or “red, D” for “hazardous” when they assessed it in 1939 (the scale moved from “A” at best to “D” at worst). Regarding the tract of West Adams where Black residents first bought homes, they said, “forty years ago this was a good medium priced residential district but since…it has rapidly become infiltered [sic] with negroes and Japanese. It is considered the best Negro residential district in the city.”[32] The appraisers labeled it “D” for “hazardous.”

The HOLC ratings were premised on an urban theory coming from the University of Chicago school of urban ecology, which asserted that urban neighborhoods would inevitably decline after construction. According to this line of thinking, the final stage of decline would see a neighborhood “infiltrated” by African Americans and other ethnic minorities, at which point appraisers would assign the neighborhood a “D” rating and warn white buyers against purchasing or even recommend the demolition of the homes in the name of “slum clearance.” HOLC ratings used this set of inherently racist assumptions to dictate the value of the urban landscape. As Calvin Bradford reveals while analyzing these appraisal methods, the underlying racist philosophy of such property evaluations continued to hold weight until the time of his writing in 1979.[33] Considering Black residents arrived in the rest of West Adams throughout the 1940s and 1950s, we can, using Bradford’s analysis and the 1939 redlining map, declare with near certainty that the rest of the neighborhood’s tracts, including Sugar Hill, would have been given “D, hazardous” appraisals by the end of that decade.

This context helps explain the decision highway officials faced when routing the Olympic Parkway. As seen on the above HOLC redlining map of Los Angeles, there was only one potential path through central Los Angeles (the right half of the map) for an east-west highway that left “green, A” and “blue, B” rated neighborhoods intact. That path would inevitably cut through some part of West Adams. State Highway Commission officials would later cite that the route they chose was the most efficient and easiest route, and that “the principal factors that enter into the selection of a parkway location are first of all the service to the motorist.”[34] For middle-and-upper class white residents living in racially homogenous neighborhoods, it certainly was the most efficient and serviceable route. Most of them were able to live near the highway without having their homes threatened by it. For residents in racially heterogenous tracts in neighborhoods like West Adams, the highway posed not an opportunity but rather the threat of demolition.

Resistance and Resolution: The Freeway’s Arrival

It did not take long for residents to organize in response to the official route announcement. A local group, first loosely referenced as Citizens Against Proposed Adams-Washington Freeway and later named the Adams-Washington Freeway Committee, convened to argue their case at the first publicly scheduled hearing at the capital in Sacramento on February 18, 1954.[35] The committee, led by Urban League of Los Angeles Executive Director Floyd Covington, attorney Bernard Jefferson, and real estate agent John Saito, argued that the freeway’s routing was discriminatory due to the disproportionate difficulties Black and other racial minority residents would face finding new housing upon displacement.[36] The committee knew from the plans that leaked from the engineer’s office that up to twelve routes had been considered and that two of these alternate routes in particular – the ones mirroring either Olympic Boulevard or Venice Boulevard – would plot the freeway through majority white neighborhoods.[37] Unlike Councilman Navarro, the committee did not come out against the freeway in its totality – they acknowledged that it was a necessary infrastructure project and that it would inevitably displace some homes. They asserted without equivocation, however, that forcing residents of color to move was not the same as asking white residents to move. John Saito spoke from his experience as a real estate broker, arguing that given ongoing discrimination in the industry, it was irresponsible for the state to displace Black and Asian-American residents without promising to work alongside them to secure replacement homes. Floyd Covington showed the Commissioners a map that selected 500 “dwelling units” under threat by the highway and “outlined limited areas where it [was] possible for the displaced persons to relocate.” [38]

This strategy – to acknowledge the freeway’s inevitability while presenting a case that their neighborhood should be spared – was likely the best option at the committee’s disposal. The State could deny that race was a factor in the routing decision by citing efficiency and cost but could not argue decisively against the difficulties residents of color would face relocating. Whether or not this would prove persuasive enough to alter the routing would remain to be seen. From the beginning, the State had the option to condemn homes if necessary, so it did not need resident approval to proceed with its desired route.[39] While the law required public comment before the route’s adoption, the calculations made by commissioners following comment sessions were likely more political than moral, and unlike in the restrictive covenant court cases there was no judge present to arbitrate the matter. Nonetheless, West Adams residents pressed on with all of the tools at their disposal to present a clear and reasonable case for the salvation of their homes.

Following the initial testimony in Sacramento, the Highway Commission scheduled a public meeting in Los Angeles to solicit more community input about the Olympic Freeway. The packed crowd that filled the State Building auditorium in Los Angeles heard from a wide variety of community members, including the members of the Adams Washington Freeway Committee. The committee again warned that, if asked to move, West Adams residents of color could be faced with “open racial conflict.” Bernard Jefferson decried the “serious gravity of injustice in the problem,” where hundreds of Black families stood to “lose everything.” The primary concern, rebutted state officials, was not race but rather “to serve taxpaying motorists” who were owed efficiency from the state. Were displaced residents not seen as tax-payers worth serving? This potent tension reveals that, at the very least, certain people were more worthy of the state’s attention than others. When the assistant engineer appealed to the committee that he recognized the problems faced by citizens in the path of the freeway, but that he felt the problems could be solved, he did not say how.[40] The engineer’s empty assurance betrayed that while the highway commission could claim race was not involved in their decision-making, they were also not interested in rectifying the plight of residents affected by racial discrimination. At the very least, the highway commission was willing to allow both existing racial disparities and the architecture of racial violence to continue to wreak havoc.

Not all of the attendees in Los Angeles that night were there to testify on behalf of the West Adams residents. A wide swath of civic agencies and community notables, including businesspeople, bureaucrats, and elected officials from the cities of Los Angeles, Santa Monica, Culver City, Beverly Hills, and Malibu, urged immediate adoption of the route through Sugar Hill. Malibu, Culver City, and Santa Monica were all autonomous cities located to the west of Los Angeles and each stood to receive significant commercial benefits from the arrival of the freeway. Beverly Hills, however, would not be served by the route at all. Rather, the representatives from the region’s most upscale city were likely eager to finalize the West Adams route because the alternative Olympic Boulevard route threatened to cut through some of their high-end shopping districts. This was one of the two alternate routes urged by the Adams Washington Freeway Committee as a more favorable option than the one that sliced through their homes. West Adams residents were not only up against the highway commission but also faced a powerful network of vested interests that sought the quick completion of the freeway on its proposed course.

In the midst of this tug of war, race remained a contentious factor. Following testimony in favor of the route by a member of the Malibu Chamber of Commerce, a local Jewish cultural leader called out, “Will Malibu accept some of the Negroes kicked out? Didn’t people there pass a resolution urging that Negroes be kept out of your area?”[41] This searing challenge highlighted the exact disparities the West Adams residents had made the core of their argument: while the law said restrictive covenants were dead, predominantly white cities and communities continued to find ways to exclude residents of color. Common practices of intimidation, real estate steering, and racially restrictive homeowner’s associations coupled with discriminatory federal mortgage lending practices made displacement a real concern for Black residents seeking new homes. The fact that certain Malibu communities had recently come under fire for deploying some of these practices only served to underscore the West Adams Committee’s argument.

The meeting in Los Angeles was contentious enough to convince the Highway Commission to delay their decision by another two months, but the case made by the Adams Washington Freeway Committee and their allies was not enough to change the route. In May, officials announced that the route would be upheld, and that construction would begin sometime the following year.[42] The disappointment and fear understandably shown by West Adams residents was documented in the African American press nationwide, which had covered the situation from the beginning.[43] Los Angeles now braced for a future without Sugar Hill. While the entirety of the West Adams neighborhood would be affected, large parts of Sugar Hill itself stood squarely in the way of the demolition crews, something that caught the attention of Black journalists around the country. The apple of Langston Hughes’s eye could no longer shine like a beacon of Black optimism. The Adams Washington committee made further appeals to both the city and the state, but eventually donated their remaining funds and gave up the fight in March of 1956.[44]

The fight against the freeway would now shift west, as communities in West Los Angeles lobbied against the next proposed segment of the Olympic Parkway. Mostly white, middle class westside residents brushed up against familiar foes: highway commissioners arguing the route was most efficient, local officials and chambers of commerce urging immediate construction of the parkway, and Beverly Hills notables pushing for adoption of the route furthest from them.[45] The result was largely similar in that residents were unable to kill the route altogether, but slight differences changed the overall tone of this fight when compared to the one in West Adams. Government documents reveal that two local organizations, the Vista Del Mar Child Care Service, and Nazareth House (Elderly Independent Living), both successfully lobbied for changes to the route so their properties and services would not be adversely affected by the freeway. A Highway Commission report reveals that these groups levied complaints during public and private meetings, convinced the government to resurvey the area, and succeeded in altering the route.[46]

While a direct comparison between the massive alterations requested by the Adams Washington Freeway Committee and the specific adjustments lobbied for by these two organizations would be irresponsible, the Highway Commission’s willingness to invest time and resources in resurveying the route nonetheless betrays a level of cooperation not seen in the West Adams case. Public officials were never on the record negotiating with or working alongside the West Adams delegation, but they had worked closely and cooperatively with Vista Del Mar and Nazareth House “from the outset.”[47] The simple fact that a well-connected trio of West Adams leaders’ impassioned pleas for assistance went ignored remains worth juxtaposing with any more favorable outcomes. The small adjustments planners made on behalf of specific organizations demonstrate that they understood the human cost of their infrastructural project, but that they would not reconsider the overall toll. The highway’s progress was seen as too crucial to delay, and West Adams residents were not seen as partners worth saving.

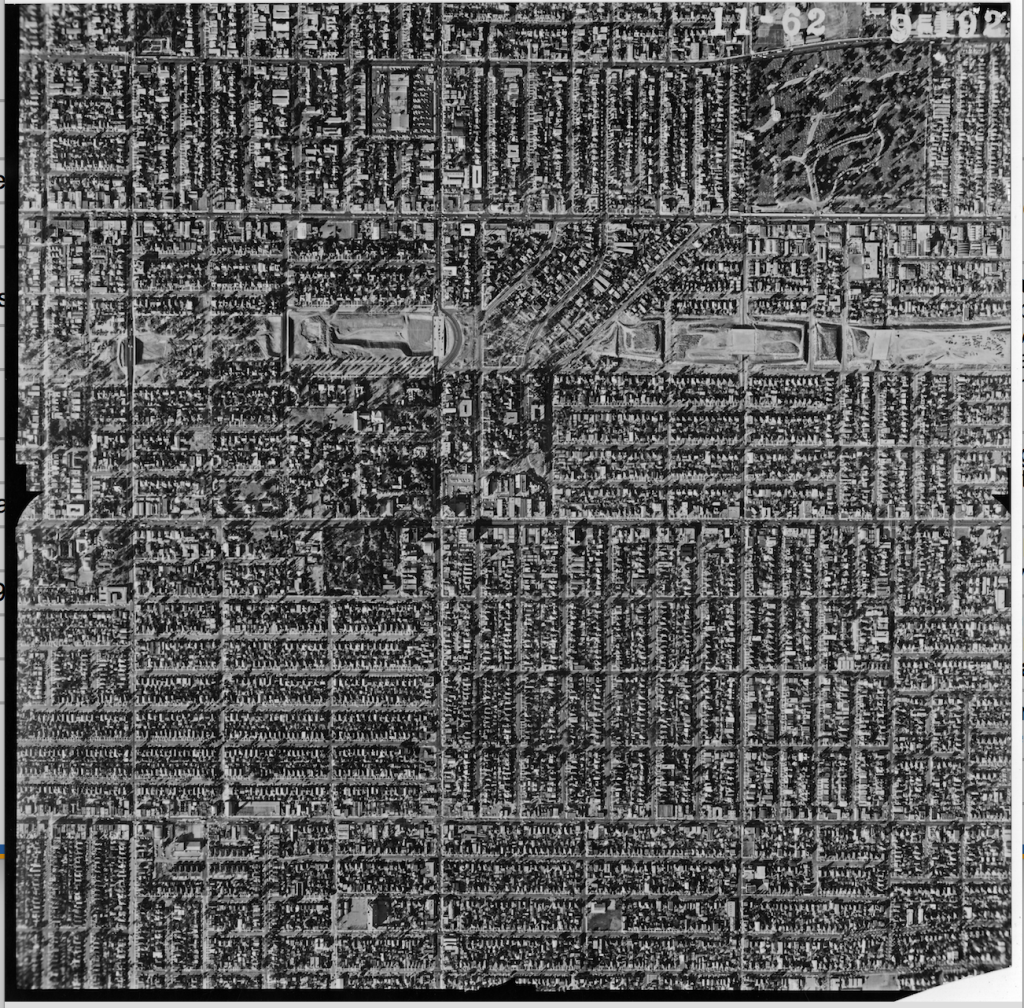

Aerial photograph taken in 1962 of highway construction cutting through the West Adams neighborhood.

Within years the freeway would arrive and the neighborhood would be forever changed. This aerial photograph, taken from an aircraft on October 1, 1962, shows West Adams in transition. This image captures the beginning of the construction of the Olympic Freeway, showing in detail the area between Arlington and Vermont Avenues (east to west) and Venice Boulevard to 38th street (north to south). The image was taken by a private photography company, Teledyne, Inc., at the request of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

The belt of absence that foreshadows the freeway’s future path serves as the focal point of the image. It is not in the true center of the image, but the way it streaks horizontally across the entirety of the frame makes it impossible to miss. Considering the image’s scale is approximately two miles by two miles, it is easy to understand the magnitude of the freeway’s intrusion. Looking carefully at the left side of the horizontal gash, it is possible to see that while most of the houses have been destroyed along the route, clusters of trees and other landscaping remain. The demolition job was not yet finished at this time. Starting at the left end of the gash and moving one third of the way to the right reveals two narrow parallel rows of palm trees lining the scattered remains Berkeley Square, the once-regal private drive. By peering closely at any point on the demolition path, one can see the ghostly outlines of yards where houses used to be, an eerie glimpse of the sites of former homes.

The image is both tied together and chopped up by strains of color and texture. The freeway’s course, presenting as a light grey, is presumably dirt. This light tone matches the light grey streaks of neighborhood streets. This textural similarity portends the freeway’s future purpose as a thoroughfare for vehicles, the sheer size at which it looms in the frame providing context for the amounts of cars that will plod across it, tracked in its cement lanes. Both the light grey streets, and the lighter grey clear-cut chop the image into parcels of land. Clusters of trees appear throughout the image and paying attention to these darker tones draws my eye toward the top right corner of the image, where the square section of winding paths and headstones comprise Angelus Rosedale Cemetery. Central Los Angeles’s dearth of parks makes this one of the few green spaces in the frame, and upon further investigation, in the neighborhood. The cemetery, large in comparison to the homes but still small in the overall frame, stands out in stark contrast to the streets and to the freeway’s path.

The utility of this image is limited by its absences. The massive scope of the aerial shot, despite presenting impressive detail, fails to capture the neighborhood at a human level. The camera’s eye floats so high that even the outlines of cars are nearly indiscernible. Humans themselves are certainly not visible, neither therefore are their comings and goings. I cannot see the storefronts, sidewalks, or stop signs that defined the neighborhood’s day-to-day life. Movement of any sort is not depicted given the scale of the freeze-frame. Wind rustling through trees and trucks whizzing down surface streets have been blurred out by pixels insufficient to capture such detail. An absence of a different sort is the homes destroyed in the demolished zone. While I have turned to local preservation websites to learn about some of these individual plots of land and their former occupants, this image itself does not dredge up the stories or scenery of its now-displaced human ecosystem.

The image’s capacious contents hold space for implications about Los Angeles, but also allude to trends in the postwar American urban environment as a whole. The 1960s saw the expansion of freeways in cities throughout the country and in rural areas to connect states and regions by automobile. The details of this image reveal the status of not just West Adams as its built environment was thrown into disarray by the freeway, but function as a prism to understand the impact of freeways on cities more broadly. The outlines of former dwellings and the shells of once-esteemed private drives provoke questions about the cultural and sociological disruption brought about by America’s turn to the automobile as its preferred method of transit. The size of the freeway’s path foreshadows the number of cars that will pass through a space once inhabited by human beings. One can better understand the material upheaval imposed by highway transit when analyzing this image of West Adams in transition. Considering federal funds were earmarked to build highways around the country, and knowing those efforts continued into the 1960s makes the contents of this image representative of broader trends in postwar urban America.

Only one region in greater Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, managed to successfully keep this national development from reaching its backyard. The powerful, wealthy, and overwhelmingly white city lobbied vigorously to oppose the Beverly Hills Freeway, which threatened to cut through their city’s most upscale environs and ruin the “stable character” of the city’s neighborhoods. By leveraging their status as an autonomously incorporated city and by hiring four different teams of consultants to conduct independent studies, Beverly Hills delayed construction for so long that the California Transportation Authority eventually canceled plans to build the freeway altogether in 1975.[48] It was only possible to wield this amount of autonomy and power in a white, wealthy neighborhood, underscoring the additional challenges faced by Angelenos of color when advocating for their place in the urban landscape. The freeway fights in West Adams and Beverly Hills were waged with equal vigor and organization, but the massive resources in Beverly Hills gave that city an unparalleled chance to win. While analyzing artistic resistance in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of East Los Angeles, Eric Avila argues that Beverly Hills’s success should not obscure our view of unsuccessful protests that occurred in other communities. Documenting “unsuccessful” resistance to freeways, according to Avila, “underscores the agency of city people of color to assert a compelling critique of infrastructural development.”[49]

Kyle Shelton similarly argues in his article, “Building a Better Houston,” that even though the results of fights against highways are inscribed with or even determined by indicators of race, class, and privilege, recognizing shared rhetoric deployed by different communities can reveal common methods citizens use to stake claims in the urban space.[50] Such an observation is certainly applicable here. West Adams and West Los Angeles residents lost their fights against the freeway, but nonetheless asserted ownership over their communal terrain in the process. While racial and socioeconomic disparities remain glaring, they are not fully deterministic but rather are reflective of the structural racism and classism endemic to American urban development. Residents of color are routinely swept aside by infrastructural change, a force fueled by an obsession with technological progress that further exacerbates existing racial and socioeconomic disparities in the urban landscape.

The story of West Adams adds an important case study to this history while bolstering these existing understandings of resistance in the urban space. The neighborhood’s high profile, economic status, and unique history of successful organizing against restrictive covenants all inform the subsequent fight against the freeway. West Adams had the tools and expertise to both mobilize and argue their case with efficacy, and they certainly did. But they could not undo decades of appraisal practices imbued with racist pseudo-science or policies that deemed their homes “hazardous” and most desirable to demolish. During the fight against the freeway, unlike in a court challenge, advocates had to convince more than just a judge to defy an existential threat. They were faced with a national consensus that touted highways as the transportation solution of the future for a booming population of economic boosters. The entire bulwark of the state, in all of its bureaucratic opacity and cold, technocratic rationality stood in their way. The fact that Sugar Hill fell to the freeway adds further evidence to the argument that race, in addition to class, determines outcomes in issues of urban environmental injustice.

The racial implications of this decision were abundantly clear, most of all to the residents themselves. The Adams Washington Freeway Committee appealed to the Highway Commission on the basis of racial discrimination and their arguments fell on deaf ears. They understood that, as residents of color, displacement put them at far greater risk than it did white residents. A Black community in Santa Monica, at the western terminus of the Olympic Parkway route, rallied to defend their community but were also met with demolition anyway.[51] That community can also be seen on the 1939 HOLC redlining map as an enclave deemed “hazardous” and primed for slum clearance.[52] The partial success of mostly white West Los Angeles and the complete success of all-white Beverly Hills further underscore the racial disparities that shaped outcomes in the freeway fights. Ultimately, the forces of structural change and institutional racism ushered in the freeway despite the strength of one of the nation’s most resilient and successful grassroots lobbies. And, despite the valiant efforts of West Adams residents, their neighborhood was saddled with the negative impacts of the highway’s intrusion.

Fallout: The Freeway After the Fight

The freeway’s impact on West Adams was drastic and set in rapidly. Of course, those most directly affected were the hundreds of families whose homes were destroyed. Left with no choice but to sell or take their case to court, they remain the primary victims of the freeway’s construction. Their homes vanished from a neighborhood where change rippled out from the highway and transformed nearly everything in the surrounding area. As early as 1964, just ten years after the highway commission announced the freeway would cut through the neighborhood, newspaper accounts show residents reminiscing about the bygone days of high society in Sugar Hill.[53] A 1971 nostalgia column refers to how, “Most of these old mansions were in the once elegant Sugar Hill section of West Adams, now gone the way of progress for a freeway and large apartment buildings.”[54] Affluent Black residents were able to chart new courses into burgeoning enclaves like Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park, View Park, and Windsor Hills, all of which were located further to the west where more open space and larger lots remained. They faced challenges from white neighbors when moving into these neighborhoods but some were able to secure homes nonetheless.[55] Despite this emigration of wealthier Black residents, the neighborhood overall became more heavily populated by Black residents and other residents of color, with the percentage of non-white residents jumping from 27.3 in 1950 to 76.7 by 1960, and again climbing to 85.1 by 1970.[56] Though white flight from central cities was common during those decades around the country, the freeway’s arrival likely accelerated the process of racial succession: white families could easily secure federally-insured mortgages to buy homes in newer, quieter neighborhoods on Los Angeles’s West Side or in nascent suburbs like Orange County to the south. The freeway certainly gave them an excuse to pursue those opportunities.

Those lacking the means to leave the neighborhood were left to cope with the serious impacts of the freeway’s arrival. Contrary to the promises of the Highway Commission, West Adams residents who stayed saw their property values drop relative to the rest of the city.[57] In 1950, the average West Adams home was worth $13,111, a sizable margin above the citywide average of $11,925. By 1960, West Adams home values had dipped just below the citywide average and by 1970, the neighborhood average value of $23,225 was well below the citywide average of $30,400. The percentage of owner-occupied homes fell by more than 50 percent between 1950 and 1970, which was reflected in the fact that many of neighborhood’s larger homes were subdivided for renters.[58] This decline in economic standing was largely reflective of disinvestment faced by central cities around the United States, but the freeway’s arrival came in the middle of the decade that would see the fastest and most intense change in both the racial and economic demographics of the neighborhood. This suggests that, at the very least, the freeway accelerated an already moving process of racialized disinvestment from the neighborhood. This is particularly striking when compared with the opportunities offered to white families who left the area: they could relatively easily build wealth through rising property values in newer portions of the city and in the suburbs.

Remaining residents lost more than property value. The freeway, which would eventually be renamed the Santa Monica Freeway (Interstate-10), dramatically re-shaped the geography of the neighborhood and brought with it worsening environmental conditions. Besides adding noise and physical blight, extensive research has also linked proximity to traffic-related air pollution to adverse health effects in both adults and children.[59] People, especially children, who live closer to freeways have been shown to suffer higher rates of new onset and exacerbated asthma, reduced lung function, respiratory system decline, and germ cell tumors.[60] The impacts of living near high amounts of traffic-related air pollution are particularly felt by pregnant women, who experience higher rates of preeclampsia and pre-term birth, and can see heightened risk of birth defects in their children.[61] Considering Interstate-10 is twelve lanes wide – carrying six lanes of cars each direction – it increases the likelihood of experiencing these adverse effects far more than a smaller two or four lane highway would.

Using the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJ Screen tool, which allows users to track and analyze both demographic and environmental data, it is possible to observe the acute effects of the freeway on West Adams. To assess this, I created a region of analysis that focuses on West Adams residents closest to the freeway by creating a 0.25-mile-wide buffer on either side of Interstate-10 between Hoover Street and Crenshaw Boulevard, as seen above.[62] Residents living in this range are in the 95th percentile in the state of California for Air Toxics Cancer risk, 93rd percentile for exposure to Diesel Particulate Matter, and 92nd percentile on the Respiratory Hazard index. These alarming statistics almost certainly stem primarily from the fact that this same region’s Traffic Proximity and Volume ranking is in the 99th percentile for the state. This data further reinforces the conclusions made by the previously cited scientific studies: it is unhealthy and potentially dangerous to live next to a freeway. Given the neighborhood experienced both significant white flight and worsening environmental pollutants after the freeway’s arrival, an strong argument can be made that West Adams is a site of environmental injustice. Residents to this day are saddled with the burdens produced by state highway officials and local interests nearly seventy years ago.

Despite these challenges, a vibrant community still flourishes in West Adams. Local organizations have worked to ensure the freeway does not obscure the rich history of West Adams and Sugar Hill. The largest and most active organization, the West Adams Heritage Association, has worked since 1983 to preserve the neighborhood’s historic architecture and educate the community about its cultural heritage.[63] Their collaborative education efforts went as far as this project, where volunteers helped me learn more about the neighborhood and provided crucial advice on seeking primary sources. Duncan McGinnis, creator of the website Berkeley Square Los Angeles, has worked meticulously to document the history of Berkeley Square, the esteemed private drive in West Adams lost to the freeway.[64] These efforts are worth pointing out when discussing the impacts of the freeway because resistance to the demolition did not end when the wrecking crews arrived: preservation and documentation remain key tools in the fight against community erasure. Current residents find themselves in a partitioned neighborhood that both reflects the urban problems of Los Angeles at large and refracts memories of the enclave’s past.

Conclusion

When Langston Hughes penned his tribute to Los Angeles’s pristine environment and tolerant racial climate, he could not have predicted the forces that would roil the city over the subsequent decades. His optimistic assessment, propelled as it was by postwar optimism, was a genuine reflection of a city on the rise and a region full of promise. The city, however, developed in such a way that it erased many of the sources of Hughes’s excitement. The streetcars gave way to automobiles, the bustling sidewalks emptied, and the freeway tore through Sugar Hill. If the neighborhood stood as a symbol for ascension, mobility, and opportunity in the poet’s account, the neighborhood remains today as a prism to interpret the challenges of the era in which the freeway was built through it.

When the nation turned toward highways to address the transportation needs of its growing population, it wrote a check that, to be cashed, required the displacement of thousands of families. It simultaneously rubber stamped a plan that would exacerbate the existing social and racial inequalities already ingrained in the country’s urban areas by disproportionately displacing residents in non-white and low-income neighborhoods. West Adams residents found themselves squarely in the path of this plan. When the Olympic Freeway route was announced, its proposed line slicing through neighborhoods appraised as “c, declining” and “d, hazardous”, residents used their formidable organizing experience to form a coalition to oppose it. They appealed to the highway commission that they would be unable to relocate as easily as white residents due to racial discrimination in the real estate market and asked that the route be diverted. While their arguments did not lack sound reasoning, the highway commission lacked compassion and patience. Technocratic, forward-minded urban planning did not have time to consider the fabric of individual communities and did not care to halt the effects of racial discrimination.

The freeway fight victories of predominantly white communities in the Los Angeles region underscore the structural racism at play in West Adams’s fate. Beverly Hills, the most glaring example, had resources and legal protections that were simply not available to even Los Angeles’s wealthiest and most well-connected Black neighborhood. This disparity of wealth, power, and privilege reveals the broader structural inequalities that often overpower even the most determined grassroots organizers during battles over the urban space. Despite West Adams’s residents’ fortitude, resolve, and bravery, the freeway tore their neighborhood in half powered by two very powerful gusts of wind: federally funded urban redevelopment and structural racism. Its arrival left remaining residents with the compounding burdens of race-based disinvestment and environmental hazards.

The freeway today acts as Los Angeles’s equator, bisecting the city nearly directly in half east to west. It is a meaningful dividing line as well as a symbolic one considering the ways it acts as a physical and demographic barrier in the middle of the city. In some ways, it manifests the old adage about the “wrong side of the tracks,” considering police dispatchers often refer to events as happening on one side or the other of the Interstate. South of the freeway, South Los Angeles, is home to Los Angeles’s largest Black communities and is on average significantly poorer than the region to the north of the freeway. Some have described the highway as a Berlin Wall, separating two halves of an unequal city that function in practice like two separate worlds, each with its own set of people, rules, and governance. Local real estate agent Adam Janeiro refers to it as a Maginot Line, just the latest in many boundaries that white Angelenos have told themselves they “won’t go past.”[65] No matter the metaphor, the highway divides the city in both its geography and in its cultural imaginary.

This past summer freeways became a site of protest during Black Lives Matter demonstrations around the country, including in Los Angeles. Protestors understood the connection between the freeways and the communities they displaced, between the concrete fortresses and the social problems they continue to intensify. At a protest in downtown Los Angeles, local pastor Stephen Cue said the freeways were part of a “long history of looting our communities, looting our lives” before leading a group of protestors up an onramp.[66] The freeway continues to emanate symbolism while reproducing environmental and cultural harm. Given the intensifying climate crisis and the longstanding racial disparities in our country, freeways remain a crucial piece of the built environment that must be interrogated. Future scholars should continue to look for the ways these structures, once the glimmering hope of a modern future, continue to reflect and reproduce the environmental and racial disparities of this country.

[1] Langston Hughes, “California Boom Town,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967); Chicago, Ill., January 26, 1946, sec. Editorial Page.

[2] Nathan Masters, “Why Did a 1542 Spanish Voyage Refer to San Pedro Bay as the ‘Bay of the Smoke’?,” KCET, March 28, 2013, https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/why-did-a-1542-spanish-voyage-refer-to-san-pedro-bay-as-the-bay-of-the-smoke.

[3] Hughes, “California Boom Town.”

[4] After assessing a range of both primary and secondary sources, it is unclear whether the neighborhood was already known as “Sugar Hill” at the time of Hughes’s visit. Many sources refer to it as “Sugar Hill” even when describing the neighborhood as it existed before the arrival of Black residents, but sources describing its early era more commonly refer to it as “West Adams Heights” or simply “The Heights.” For the purposes of this article, I will use both the terms “West Adams Heights” and “Sugar Hill” when referring to this enclave within West Adams – the former term when describing the area before it became an African American neighborhood and the latter, after it had become one.

[5] Jennifer Mandel, “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills’: The Struggle for Housing Equality in Modern Los Angeles” (Ph.D., United States — New Hampshire, University of New Hampshire, 2010), 169.

[6] For popular accounts see: Mike Sonksen, “The History of South Central Los Angeles and Its Struggle with Gentrification,” KCET, September 13, 2017, https://www.kcet.org/shows/city-rising/the-history-of-south-central-los-angeles-and-its-struggle-with-gentrification. Also see: Hadley Meares, “The Thrill of Sugar Hill,” Curbed LA, February 22, 2018, https://la.curbed.com/2018/2/22/16979700/west-adams-history-segregation-housing-covenants.

[7] Sides, L.A. City Limits.

[8] Mandel, “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills.’”

[9] Kyle Shelton, “Building a Better Houston: Highways, Neighborhoods, and Infrastructural Citizenship in the 1970s,” Journal of Urban History 43, no. 3 (May 2017): 421–44.

[10] Eric Avila, “L.A.’s Invisible Freeway Revolt: The Cultural Politics of Fighting Freeways,” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 5 (September 1, 2014): 831–42.

[11] Eric Avila, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles, First edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[12] Josh Sides, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 98.

[13] Duncan Maginnis, “Berkeley Square: Resurrecting a West Adams Street Lost to the Freeway,” 2015, https://www.berkeleysquarelosangeles.com/.

[14] Sides, L.A. City Limits, 98-99.

[15] Donald Bogle, Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams: The Story of Black Hollywood, Annotated edition (New York: One World, 2006), 200-205.

[16] Sides, L.A. City Limits, 98.

[17] ibid, 99.

[18] Mandel, “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills,’” 108-112.

[19] “Calif. Covenants Case to Be Aired,” Afro-American (1893-1988); Baltimore, Md., September 14, 1946. ; “California High Court to Rule on Covenants Oct. 2,” Cleveland Call and Post (1934-1962); Cleveland, Oh., September 14, 1946. ; “Coast Judge Rules Restrictive Is ‘Un-American,’” Philadelphia Tribune (1912-2001); Philadelphia, Penn., November 4, 1947. ; Lawrence Lamar, “Film Stars Face Eviction from West Coast Homes: Covenant Suit Threatens to Oust Notables, Hollywood Elite May Be Forced Out Of Sugar Hill,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967); Chicago, Ill., October 7, 1944.

[20] Sides, L.A. City Limits, 99-100.

[21] Joseph F. C. DiMento, Cliff Ellis, and Robert Gottlieb, Changing Lanes: Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2012), 104.

[22] Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, 1st edition (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1987), 170-171.

[23] Cecelia Rasmussen, “From the Archives: Did Auto, Oil Conspiracy Put the Brakes on Trolleys?,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2003.

[24] “Los Angeles Population History,” accessed December 10, 2020, http://physics.bu.edu/~redner/projects/population/cities/la.html.

[25] Los Angeles County Regional Planning Commission, Freeways for the Region: 1943 (Regional Planning Commission, County of Los Angeles, 1943), 10.

[26] ibid, 58.

[27] California Highways and Public Works, July-August 1952, (California Department of Public Works, Sacramento, 1952), 68.

[28] “FREEWAY ROUTE NOT ‘SETTLED’: Freeway Study Expected,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., September 3, 1953.

[29] “Councilman ‘Not Convinced’ on Need For New Freeway,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., September 24, 1953.

[30] “Volunteers Sought,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., February 25, 1954.

[31] Avila, “L.A.’s Invisible Freeway Revolt,” 833.

[32] “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” Mapping Inequality, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

[33] Calvin Bradford, “Financing Home Ownership: The Federal Role In Neighborhood Decline,” Urban Affairs Quarterly 14, no. 3 (March 1, 1979): 313–35.

[34] “FREEWAY ROUTE NOT ‘SETTLED’: Freeway Study Expected,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., September 3, 1953.

[35] Sides, L.A. City Limits, 124.

[36] The Adams Washington Freeway Committee’s primary line of argumentation – that residents of color would be disproportionately burdened in their search for new homes – is noted in Sides’ L.A. City Limits and in Mandel’s “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills.’” They both cite the California Eagle, a local newspaper. From this point forward in the essay I will add significantly to this historical account by analyzing articles from the Los Angeles Sentinel, records from the California State Highway Commission Meeting Minutes, and other government documents.

[37] “FREEWAY HEARING SCHEDULED FOR MARCH 23: State Commission To Air Freeway Hassle,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., February 25, 1954.

[38] California Highway Commission, Minutes: February 18, 1954 (Sacramento, CA: California State Library, 1954).

[39] Dora H. Moore, “This Way FOLKS!,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., September 3, 1953.

[40] “NO FREEWAY RULING BEFORE APRIL 21: Crowd Attends Hearing,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., March 25, 1954.

[41] ibid.

[42] Kenneth C. Field, “STATE ADOPTS FREEWAY ROUTE: Further Action Planned,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., May 27, 1954.

[43] “Highway To Erase LA’s Beautiful ‘Sugar Hill’ Area,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967); Chicago, Ill., March 13, 1954; “New Freeway Dooms Negro Homes,” New York Amsterdam News (1943-1961), City Edition; New York, N.Y., September 12, 1953.

[44] “Group Divides ‘Fight’ Funds,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., March 1, 1956.

[45] “Freeway Will Ruin Homes, Board Told: Residential Areas on 80% of Route, Legislator Claims,” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Los Angeles, Calif., September 30, 1955.

[46] California Division of Highways, Report and Findings of Hearing Commissioners of the California Highway Commission Re Freeway Location VII-LA, SMca (Olympic Freeway): Hearing, September 14, 1956. (Sacramento, CA, 1956), 19, 20.

[47] ibid, 21.

[48] Avila, “L.A.’s Invisible Freeway Revolt,” 834.

[49] ibid, 841.

[50] Shelton, “Building a Better Houston: Highways, Neighborhoods, and Infrastructural Citizenship in the 1970s,” 435–38.

[51] Sides, L.A. City Limits, 124.

[52] “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” Mapping Inequality, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

[53] Jessie Mae BROWN, “Your Social Chronicler: Jessie Mae Brown,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., June 18, 1964.

[54] Stanley G. Robertson, “L.A. CONFIDENTIAL: Do You Remember When…,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., May 20, 1971.

[55] Mandel, “Making a ‘Black Beverly Hills,’” 133.

[56] United States Census of Population: 1950, vol. 3, Census Tract Statistics, ch. 28 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1952).; United States Census of Population: 1960, vol. 3, Census Tract Statistics, ch. 1 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1962).; United States Census of Population: 1970, vol. 3, Census Tract Statistics, ch. 10 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1972).

[57] “Olympic Freeway Commentary,” Los Angeles Sentinel (1934-2005); Los Angeles, Calif., June 10, 1954.

[58] United States Census of Housing: 1950, vol. 5, pt. 100 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1952).; United States Census of Housing: 1960, vol. 3, pt. 2 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1962).; United States Census of Housing: 1970, vol. 5, pt. 3 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1972).

[59] Nino Künzli et al., “Breathless in Los Angeles: The Exhausting Search for Clean Air,” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 9 (September 1, 2003): 1494–99; Patricia van Vliet et al., “Motor Vehicle Exhaust and Chronic Respiratory Symptoms in Children Living near Freeways,” Environmental Research 74, no. 2 (August 1, 1997): 122–32; C. J. Gabbe, “Residential Zoning and Near-Roadway Air Pollution: An Analysis of Los Angeles,” Sustainable Cities and Society 42 (October 1, 2018): 611–21; Trevor S. Krasowsky et al., “Characterizing the Evolution of Physical Properties and Mixing State of Black Carbon Particles: From near a Major Highway to the Broader Urban Plume in Los Angeles,” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 18, no. 16 (2018): 11991–12010.

[60] Julia E. Heck et al., “Childhood Cancer and Traffic-Related Air Pollution Exposure in Pregnancy and Early Life,” Environmental Health Perspectives 121, no. 11–12 (2013): 1385–1391.

[61] Jun Wu et al., “Association between Local Traffic-Generated Air Pollution and Preeclampsia and Preterm Delivery in the South Coast Air Basin of California,” Environmental Health Perspectives 117, no. 11 (2009): 1773–79.

[62] Environmental Protection Agency, “EJ Screen: EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool,” https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper. The EJ Screen data analysis followed Interstate-10 from Hoover Street to Crenshaw Boulevard, with a .25 miles buffer defining the region of analysis.

[63] For more information on the West Adams Heritage Association and the work they do, please visit their website: https://www.westadamsheritage.org

[64] The website https://www.berkeleysquarelosangeles.com is connected to a larger project, Historic Los Angeles, that seeks to document for the public lost histories of neighborhoods, buildings, and streets in the city of Angels.

[65] Hadley Meares, “Why L.A.’s Freeways Are Symbolic Sites of Protest,” Curbed LA, June 11, 2020, https://la.curbed.com/2020/6/11/21281263/los-angeles-freeway-history-protests.

[66] ibid.

Primary Sources:

County of Los Angeles Regional Planning Commission. Freeways for the Region. Accessed through Metro Library Archives. http://libraryarchives.metro.net/DPGTL/trafficplans/1943_freeways_for_the_region.pdf1943.

Freeways for the Region is a seminal document that lays out the justifications for building a freeway system in Los Angeles County. This document provides the original context for the shift in transportation towards automobile travel and will allow me to explain the genesis a truly interconnected system of freeway travel in Los Angeles. It also offers a history of previous proposals that had set the table for future plans, including plans by the Automobile Club, a Citizen’s Committee Plan, and a Los Angeles City Plan. This sixty-page document is full of maps, sketches, and cartoon advertisements that provide propagandized justifications for investing in urban freeways. Considering this proposal is comprehensive and full of subjectivity, it will allow me to analyze the political, fiscal, and cultural context of the era of freeway expansion.

Telford, Edward T. California Highways and Public Works. District VII Freeways Report: Accomplishments During 1956 and Outlook for Future. Accessed through Metro Library Archives. 1957.

Click to access chpw_1957_janfeb.pdf

Similar to the first highway report, this report provides context to the construction of Interstate-10 in the early 1960s. This document details recent achievements in building the freeway system and discusses plans for the immediate future. Primary sources like this are crucial to situating my argument in the context of federated government, and this gives me a detailed account of machinations at the state level. The report also includes diagrams and maps of proposed future freeway routes, including the Santa Monica Freeway/Interstate-10. Comparing this source with Freeways for the Region, I will be able to analyze changes in the regional plan and trace how those changes affected different Los Angeles neighborhoods and their residents.

Bradford, Robert B. California Highways and Public Works. California Highways, 1962. Accessed through Metro Library Archives. 1962.

Click to access chpw_1962_novdec.pdf

This 1962 statewide report will allow me to complete my three-fold analysis of the highway commission’s planning for the Los Angeles region. If the first two documents provided the long-term and immediate foreground to the Santa Monica Freeway construction, this report details the immediate aftermath. This includes maps, financial figures, and pictures of accomplishments throughout the state in the 1961-1962 fiscal year. I will use this report to analyze the official state narrative on freeway construction during the year I am most specifically focusing on. I will pay close attention to any route changes, construction delays, and editorializing of the construction and will scour the document for hints at where to find other primary sources.

Census of Population and Housing, 1960, Final Report Series PHC (1), Census Tracts: Los Angeles-Long Beach. Accessed through U.S. Census Bureau.

Click to access 41953654v5ch04.pdf

The 1960 census details the racial and socioeconomic demographics of Los Angeles immediately before the construction of Interstate 10. The report is broken down in to census tracts, which I can use to assess the composition of neighborhoods impacted by freeway construction. I can then compare this data with the data in 1970 and 1980 to measure the impacts of the freeway on the racial and socioeconomic demographics of the neighborhood. This will prove crucial as I set out to answer whether Interstate-10 has had a polarizing and segregating effect on the neighborhood and on the entire mid-city region of the city.

Aerial Footage of West Adams with Arlington and Gramercy overpasses. 1961. Originally located in UCSB Aerial Photograph Archives, accessed courtesy of West Adams Heritage Association. Second photo is a Google Maps screenshot of the same parcel today.

Analyzing images will be a key part of my research project, considering I am studying the impacts of changes in the built environment. The first photo is a gold mine of analytical possibility: it contains remnants of plots destroyed during construction, shows traces of Berkeley Square, a well-documented cultural landmark in the West Adams neighborhood, and evokes strong imagery of a neighborhood in transition. Places images like this in my work will give me an opportunity to draw readers into the physical impacts of neighborhood transition and will bolster data and evidence found in reports and planning documents.

Secondary Sources:

DiMento, Joseph F. C., Cliff Ellis, and Robert Gottlieb. Changing Lanes: Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways. Cambridge, UNITED STATES: MIT Press, 2012.

DiMento’s and Ellis’s book provides a sweeping overview of urban highway construction in the United States from the 1930s to the end of the twentieth century. This work lays out the public policy context of highway construction and will help me situate my research in the broader context of urban roadway scholarship. The book also includes a chapter of case studies, one of which follows litigation against the Century Freeway in Los Angeles. This section gave me a better sense of the local and national political interests that both drove and opposed highway construction in Los Angeles and will likely serve as an important backdrop in any analysis that I write about a specific Los Angeles neighborhood. The comparisons in that section – to both Memphis and to Syracuse – will guide me as I try to determine the scope of my conclusions both geographically and temporally.

Avila, Eric. “L.A.’s Invisible Freeway Revolt: The Cultural Politics of Fighting Freeways.” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 5 (September 1, 2014): 831–42.

Eric Avila’s article discusses highway construction in the East Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights. He argues that, while most accounts of resistance to freeways focus on wealthier neighborhoods like Beverly Hills, poorer neighborhoods of color also resisted – even if that resistance was creative, artistic, and cultural, and did not result in the defeat of the proposed projects. This analysis provides a helpful point of thematic comparison for my own study, especially since I am investigating neighborhoods that did, eventually end up being destroyed. His text prompts me to ask if and how West Adams and adjacent residents fought the freeway’s advance and makes me wonder if I will have to look at creative forms of resistance in addition to legal and political battles. Avila’s focus on the role that race, not just class, played in the plight of East Los Angeles residents is also crucial as I set out to analyze the destruction of an affluent Black neighborhood.

Künzli, Nino, Rob McConnell, David Bates, Tracy Bastain, Andrea Hricko, Fred Lurmann, Ed Avol, Frank Gilliland, and John Peters. “Breathless in Los Angeles: The Exhausting Search for Clean Air.” American Journal of Public Health 93, no. 9 (September 1, 2003): 1494–99.

This article, published in a public health journal, analyses the causes and impacts of air pollution in Los Angeles. This scientific study will help me broaden my analysis of the built environment to include the health impacts of living near a freeway. This context is crucial as I investigate the impacts of freeway construction in central Los Angeles. Not only will I need to familiarize myself with the pollution impacts of urban freeways, I will also need to compare these impacts to those stemming from other sources of pollution. This article is written with such scope in mind and will give me several points of reference when situating my study within the broader urban public health discourse of air pollution in Los Angeles.

Shelton, Kyle. “Building a Better Houston: Highways, Neighborhoods, and Infrastructural Citizenship in the 1970s.” Journal of Urban History 43, no. 3 (May 2017): 421–44.

This article is a model study in urban freeway construction and grassroots resistance. Kyle Shelton details the fight of two different urban communities in Houston – one affluent and white, the other mostly poor and Black – against freeway construction in their neighborhoods. This article analyzes factors of race and class when comparing the rhetoric and strategies employed by each group. While I have not yet found conclusive evidence of popular resistance against the construction of I-10, this article lays out a model for diving deeper into this history in its bibliography – considering both the primary and secondary sources Shelton uses. The periodization here is also helpful: Shelton focuses on the 1960s and 1970s, which is the era I will be investigating. While Changing Lanes presents a case study on a Los Angele neighborhood, the Century Freeway fight happened much later than the construction of I-10 and therefore is positioned within a different political, social, and demographic context.

Nall, Clayton. “The Political Consequences of Spatial Policies: How Interstate Highways Facilitated Geographic Polarization.” Journal of Politics 77, no. 2 (April 2015): 394–406.

Considering I am interested in exploring the demographic and social impacts of Interstate-10’s bisecting of the city of Los Angeles, this study in political realignment following highway construction gives me a place to start. Despite the fact that this article focuses on ideological realignment, not realignments of race and class, the latter two factors are included as context for the aforementioned political analysis. Clayton Nall argues that intraurban polarization and regional polarization both directly increased as a result of both urban and suburban freeway construction. I can use this analysis to both contextualize and bolster an argument about the demographic and social – and by extension disparate environmental – implications of freeway construction in Los Angeles.

Image Analysis:

This aerial photograph, taken from an aircraft on October 1, 1962, shows the Los Angeles neighborhood of West Adams in transition. Known for being the residence of many middle and upper class African American Angelenos, many of its stately homes were destroyed when the highway commission’s bureaucratic knife sliced through the stomach of the neighborhood. This image captures the beginning of the construction of Interstate 10 in mid-City Los Angeles, showing in high resolution detail the area between Arlington and Vermont Avenues (east to west) and Venice Boulevard to 38th street (north to south). The image was taken by a private photography company, Teledyne, Inc., at the request of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Having access to this image is extremely valuable to my project, given the visual prominence of the clear-cut left behind by demolition crews when they prepared a way for the freeway. Crucially, the outlines of old plots of land and even the trees of the once-esteemed Berkeley Square remain visible, allowing me to trace the recent presences of buildings alongside the future of the concrete river that replaced them. This aerial image provides a detailed overview of what was gained and lost when the freeway arrived in West Adams, giving an insightful window into the impacts of construction on the neighborhood’s built environment.