Highway to Disaster: How the Creation of the New Jersey Turnpike Caused Destruction and Lasting Impacts on the Residents of Elizabeth, NJ

by Hayat Abdelal

Site Description:

The New Jersey Turnpike was officially opened for travel on November 30, 1951. The construction of the highway cost millions of dollars including the cost of relocation of industrial facilities. At one point during the construction a decision had to be made whether to build a route that would destroy 450 homes or 32 businesses in Elizabeth, NJ. Ultimately, the decision was made to build through the residential area and demolish the houses. This decision is written off as an inconvenience in the history of the construction of the NJ Turnpike. However, the plowing through a city and cutting neighborhoods in half certainly had drastic effects on the communities living there. My research will focus on the community impacted by the construction of the highway in the 1950s in Elizabeth, NJ. What happened to the residents whose homes were destroyed? How did the residents who remained deal with the impact of smog and major construction now in their backyard? The significance of this research is to understand how construction can have long term effects on communities and to bring attention to injustices caused by highway building and expansions still happening today.

Final Report:

Driving down the NJ Turnpike I am greeted with a beautiful landscape on the horizon. I begin to admire the open natural environment, a sight I do not usually see daily in North Jersey. As I continued to drive down the Turnpike, the scenery began to shift into the more familiar urban landscape. The tall industrial buildings and the dark smoke that was threatening the beauty of the blue sky are now in my line of sight. At this point in my trip, I knew I was driving through the city of Elizabeth as planes flew overhead to land into the Newark airport on my left. This not so scenic part of my trip made me question how did all these industries come to cluster on the side of the highway? I continued my journey taking in my surroundings driving on a road that existed long before I could drive.

The scenery on the highway I had come to admire many years after the creation of the Turnpike was not an accident. At the opening of the New Jersey Turnpike Governor Driscoll said, “The Turnpike has permitted New Jersey to emerge from behind the billboards, the hot dog stands and the junkyards. Motorists can now see the beauty of the real New Jersey.”[1] The irony of this statement paves the way for a closer look at the impact of the Turnpike. The beauty of NJ Driscoll aimed to highlight through the highway lead to destruction of land and natural systems. The junkyards he wants to avoid and push away hint at the larger issues of institutional racism that disenfranchise urban communities perpetuated by constructs that include highways.

Scholars have focused on the environmental impacts the highway has on America by looking at the changing landscape and its impacts on communities of color. In Car Country: An Environmental History, Christopher Wells argues that the American environment has been shaped by the automobile into a car-dependent landscape and he analyzes the change in American ecology and impacts on the environment from the automobile. Other literature, including the work of Robert Bullard, addresses the racial injustices that are tied to the environmental injustices that come from highways. What these sets of literature are missing is the impacts of the existence of the highway after it has been constructed.

Understanding the impacts of the presence of the highway relies on first understanding the lucrative connection highways have to industry. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published research establishing a relationship between economic success of industry to the construction of highways. Decisions made on the construction of highways were previously focused on the benefits of accessibility and mobility. However, the goal of construction shifted as evidence showed that “it is clear that public investments to increase the economic impact of the highway network result in important monetary benefits for the private sector.”[2] It accounted for 25 percent of average annual productivity growth in the US from 1950 to 1989.[3] The FHWA included a disclaimer stating that the scope of the research did not cover the social and environmental impacts the relationship between highway and industrial growth has. This gap will be explored in this paper.

Elizabeth, NJ is representative of what happens to urban communities when a highway becomes a fixture of a city and is overwhelmed by a significant industrial presence that followed the creation of the highway. There has been ample amount of research examining the impact of the many cities plagued by destruction of land and construction of highways, such as Miami and Detroit.[4] However, the impact of the NJ Turnpike cutting through Elizabeth has not been well documented. The similarities of circumstances and minority population warrants a comparison of the conditions in Elizabeth to the more well researched cities. Furthermore, the NJ Turnpike was officially opened in 1951 falling within the time period of 1951 to 1989 the FHWA cites as a period of economic industrial growth tied to the presence of highways. For these reasons Elizabeth, NJ is a great sample for looking at the impact of industry that the presence of a highway invites.

This paper will explore the relationship the highway has to industry and the pull the highway has to entities that inevitably draw various sources of pollution. The phenomenon of the aftermath of the highway raises these questions: How does a highway impact and change the land that surrounds it? What does the access the highway provides mean for the businesses looking for real estate? How does the pollution the highway structure causes extend to effects beyond its lanes? The NJ Turnpike’s existence through the city of Elizabeth NJ creates a magnetism to industry that are sources of greater pollution that continues to affect the minority population in the area.

To explore this argument the paper will initially give a brief history of the decisions made when the NJ Turnpike was constructed and its impact on Black residents. It will then be followed by an analysis of industrial sites including the Newark Airport and the shopping mall, The Mills at Jersey Gardens. The presence of these sites is rooted in the existence of the highway and these industries exist as various pollutants contributing to the overall environmental issues in the city. These issues will be represented by a brief analysis of data from the Environmental Protection Agency. An explanation will follow of how industry is a major contributing factor to the environmental hazards which includes the proximity to hazardous chemicals and water. Finally, concluding remarks will be made concerning the relationship of highways to industrial sites. Below is a brief video highlighting some points this paper covers.

For an overview of this project, please see the video story below:

The Turnpike and Elizabeth, NJ

The NJ Turnpike was previously referred to as Route 100 and articles in the Newark Star-Ledger followed the story of what plan for the highway would be chosen. The ongoing issue was the planned route would either destroy 450 homes or 32 businesses.[5] The proposed plan was referred to as the Fourth Street Route. Thomas E. Collins, the city engineer, proposed a waterfront route that would only impact 15 homes, but his plan was rejected. The article in the paper noted that Collins route would also cause less of an impact on tax ratables, which are properties that produce a tax income for the local government to use. The Fourth Street Route would cost the city $11.2 million in taxable property versus only $500,000 loss under the waterfront route.[6] The Turnpike Authority was however adamant about the Fourth Street route and ignored the protests and alternate suggestions from the community in Elizabeth.

In a last resort attempt to preserve the city, a lawsuit was filed against the New Jersey Turnpike Authority. The headline for the newspaper article on March 2, 1950 read, “Elizabeth Launches Court Fight to Bar ‘Chinese Wall’ Toll Road,” the barrier and separation the highway was set to create earned it the notorious nickname “Chinese Wall”. The lawsuit charged that the Turnpike Authority’s insistence on the Fourth Street Route violated the constitutional rights of the residents. It also stated that the Turnpike Authority received some federal funding and laws prohibit tolls on roads for which the federal government helped fund.[7] The decision was made by the New Jersey Superior Court on March 24th, 1950. The decision ruled in favor of the Turnpike Authority noting that the Fourth Street Route was the only “feasible” one. The ruling also indicated that the NJ Turnpike Authority “did not act precipitately or in disregard of the plaintiff’s rights; on the contrary, it made its decision after full consideration of the factors involved.”[8] Although they may have considered all the factors, it was in disregard to residents’ rights, specifically the Black population in Elizabeth.

The analysis of the demographics in the city points to a racial disparity in the displacement the Turnpike caused in Elizabeth. The map below displays the percentage of Black residents in Elizabeth during the 1940s based on Census data. The darkest shade of orange on the map represents 15% to 30% of Black residents in that section of Elizabeth. It is followed by 10% to 15% and 5% to 10% as the three areas with the greatest percentage of Black residents. The area almost creates a triangle, which eventually was bisected with the creation of the NJ Turnpike. The highway is labeled as I-95 on the edge of the color change (I-95 was created after the Turnpike and routes through the Turnpike). The route in Elizabeth chosen for the Turnpike was the one that would splice and disconnect the residential area containing the highest percentage of Black residents. In St. Paul, Minnesota the Interstate 94 also cut through the city and a critic of the construction stated, “very few blacks lived in Minnesota, but the builders found them.”[9] The Turnpike Authority actions and refusal to alter their route was a clear racial injustice.

Figure 1: Map of Census Data on Race, 1940[10]

Data from today’s census presents Elizabeth as a more diverse city of different minority populations. The population of Elizabeth, NJ is 64.5% Hispanic or Latino according to the most recent Census data shown in figure 2 below. The second largest group is White, alone at 45%, but that is categorized as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as “White” or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Arab, Moroccan, or Caucasian.”[11] This definition does not give an accurate breakdown of the population of minority groups. However, the data also shows that the foreign-born population between 2014-2018 is 46.2%. This points to a larger immigrant population than the percentage of White may suggest.

Figure 2: Elizabeth, NJ Demographic Census Data, 2019[12]

The economic status of the residents in Elizabeth is also an import part of understanding the demographic. The total population is 129,216 and of that 18.6% are in poverty and the median household income (in 2018 dollars) 2014-2018 was $46,975. Overall, the demographic points to a large minority group in the lower economic bracket. According to data from 2017, the average income to afford a two bedroom was $56,810 and a one bedroom was about $46,619. However, according to the census data there are about 3.12 persons per household, 2014-2018. This means that most people have others living with them and can barely afford a one bedroom. The economic struggles are highlighted by the fact that “minimum-wager earners in New Jersey would have to work a whopping 106 hours per week to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment at the fair market rent of $1,165 per month.”[13] As a result, overcrowding can become an issue and it can be difficult to find adequate housing or an oasis from the poor air quality that engulfs the city. Environmental and socio-economic issues seep into the home and into different aspects of life as the surrounding landscape is at the mercy of the highway and industry that shaped it.

The NJ Turnpikes accessibility was a highlight of its construction, but its relationship to the Newark Airport was also an essential component to how the route was planned. In the debate on whether to cut through the 32 businesses versus the homes that would impact 450 families, “the engineers decided to go through the residential area, since they considered it the grittiest and the closest route to both Newark Airport and the Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal seaport.”[14] The benefit was that it would cut the commute from the Newark Airport to 42nd Street in New York where Port Authority is located to within a 15-minute timeframe.[15] This fact emphasizes the relationship the highway had to the airport industry from its inception. The NJ Turnpikes’ relationship to industry was established before its construction was even complete.

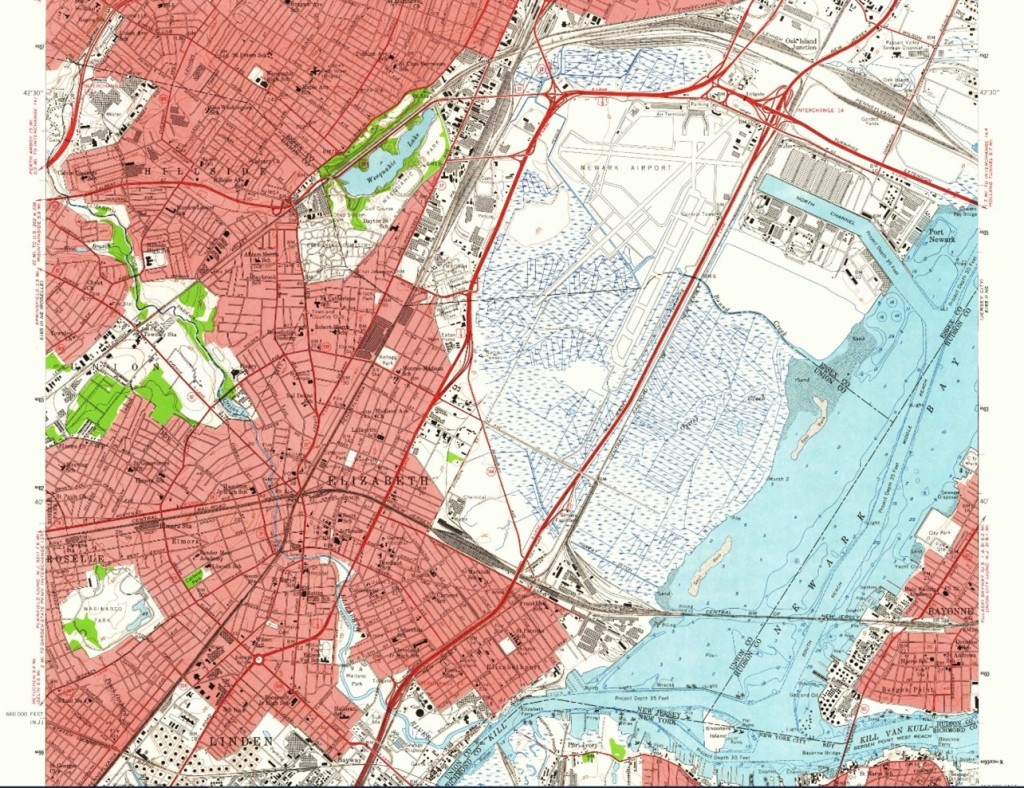

The Newark Airport’s expansion is indicative of the economic growth and success it had after the Turnpike was built, represented in the FHWA study, but this growth also brings pollution to the area. The airport is located between Elizabeth and Newark and the airport’s expansion can be analyzed by comparing the three maps below. In 1947 the airport was relatively small and surrounded by small bodies of water. By 1955 the NJ Turnpike’s construction was completed and the dark red lines indicate roads that are classified as heavy duty, this includes the NJ Turnpike that is represented by the red line on the right side of the airport. The final map depicts the present day, 2020 and the airport has expanded to fill the entire space where the water once existed. The disappearance of the water and open land stripped the land of natural ecosystems. The air pollution and noise the airport brings to the residents of the area is also a major disruption, especially for the minority population who are impacted more heavily due to the lack of access to the care they need to address the health risks caused by the environmental hazards. The pollution leads to health concerns like heart problems and respiratory issues, including asthma.[16] The current airport’s large and undeniable presence in the city is a hallmark of the environmental issues and health risks.

Figure 3: Map of Elizabeth 1947[17]

Figure 4: Map of Elizabeth, 1955[18]

Figure 5: Map of Elizabeth, 2020[19]

A more immediate impact of the airport after the construction of the highway were tragic plane crashes into the city. Three planes crashed in Elizabeth within the span of 58 days after the highway’s construction was complete in November 1951.[20] In December of that year a plane crashed into a building along the industrial stretch of the Elizabeth River. A month later in January another crash happened, but this time into a row of homes. Still the Newark Airport did nothing despite the mayor’s protests. Then, a few weeks later on February 11, 1952 a Congressional subcommittee hearing was scheduled to discuss the residents’ protests who wanted the airport closed versus Port Authority’s pre-published defense that the airport was one of the safest in the U.S. But then that same day another airplane crashed into a four-story apartment building near an orphanage. The airport was then shut down until November 1952 after a new runway was created that directed air traffic away from Elizabeth. An oversight in the original construction of the highway and expansion of the airport was one that resulted in tragic loss and devastation for the residents in Elizabeth.

The mall stands as another large industry that was attracted to Elizabeth due to the presence of the NJ Turnpike. Referring back to the map of present-day Elizabeth, two large structures exist to the right of the airport on the other side of the highway, Ikea and an outlet mall, The Mills at Jersey Gardens. The mall was opened in 1999 in Elizabeth on an area that was the Union County landfill. The dumping there had ceased in 1972 but had not been decontaminated. Places like Elizabeth are then inclined to make deals with developers who will clean up the site, but this usually comes at the cost of agreeing to denser projects they would not otherwise want in their city. Denser projects being ones that generate “more demand for town services, more traffic and more pollution.”[21] Why would a major industry like a mall want to build on a landfill anyway? These sites are attractive because of their large size, but also because landfills “often adjoin ‘solid infrastructure,’ like well-maintained roads and utility hookups.”[22] The presence of the New Jersey Turnpike attracted a landfill near it and when that was no longer in use decades later, the highway was still a viable and functional entity that was attractive to the developers of the mall. Industries’ success relies on the access to it and so developers seek out that which will garner more revenue and which they cannot exist without, proximity to a highway.

The highway invites industry to surround it and these sites bring pollution to the area and The Mills at Jersey Gardens is amongst the industries contributing to the pollution in Elizabeth. There are several attributes of a mall that cause environmental concerns. One of them being the traffic caused by the consumers because “not only that traffic increases substantially in the vicinity of malls, but cars are usually driven at slow speeds when most of the toxic exhaust is generated.”[23] The retailers in the mall and food court are also contributors to air pollution from the chemicals they generate that are volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These can arise from leather products, cooking stoves, or the selling of chemical products like paint and building materials.[24] The landfill became prime real estate for a mall, one source of industry was replaced by another, but both cause an immense amount of pollution to the area.

The Turnpike’s Environmental Footprint

An overall look at the environmental issues plaguing Elizabeth can be analyzed by looking at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Data. The EPA provides an environmental justice mapping and screening tool that exhibits information using an EJ index which is a combination of demographic data and environmental data. This information reveals that Elizabeth’s traffic proximity and volume is in the 94th percentile in both the state and country. The NJ Turnpike is a major contributor to this statistic. The city’s index for Hazardous Waste Proximity is in the 90th percentile for New Jersey and the 95th percentile in the U.S. Additionally, Elizabeth ranks very high in the index for “Wastewater Discharge Indicator” at 97th percentile for the state and 95th percentile in the country.[25] The high density of development is the source of these pollutants.

The industries that established themselves alongside the Turnpike have tainted Elizabeth’s water with pollution and have left residents with unsafe drinking water. There are minimal federal regulations on water and standards have not been updated in decades and some chemicals have no standards or limits for tap water.[26] The Environmental Working Group (EWG) utilizes updated standards for tap water to provide more comprehensive information by testing water and providing a database on tap water for zip codes. Elizabeth’s water comes from two sources NJ American Water-Liberty located in Elizabeth that is purchased surface water and from the Newark Water Department that is sourced from surface water. There are contaminants in both of these sources of water that impact thousands of residents. Some of the contaminants in the water are from the industry’s runoff and sprawl, caused by rainwater which leads the contaminants from the industry to the bodies of water. The table below lists only the sources of contamination that are caused by development. The industry pollutes the water and becomes a source of both environmental and racial injustice as the lives of the largely minority population of Elizabeth is being put at risk by these toxins in the water.

Figure 6: Table of Water Contamination in Elizabeth’s Tap Water (Info sourced from EWG Site)[27]

| Water source | Contaminant | Risk | Pollution Source |

| Both | Chromium (hexavalent) | “Chromium (hexavalent) is a carcinogen that commonly contaminates American drinking water. Chromium (hexavalent) in drinking water may be due to industrial pollution or natural occurrences in mineral deposits and groundwater.” | Industry, Naturally Occurring |

| Newark Water Source | Radium, combined (-226 & -228) | “Radium is a radioactive element that causes bone cancer and other cancers. It can occur naturally in groundwater, and oil and gas extraction activities such as hydraulic fracturing can elevate concentrations.” | Industry |

| Newark Water Source | 4-Androstene-3,17-dione | “Human sex hormones are sometimes detected at low concentrations in drinking water. There are no current health guidelines to determine whether these exposures are safe, or if they could pose a risk to human health.” | Runoff & Sprawl |

| Newark Water Source | Aluminum | “Aluminum is a metal released from metal refineries and mining operations. Too much aluminum exposure can impair children’s brain development.” | Industry, Naturally Occurring |

| Newark Water Source | Barium | “High concentrations of barium in drinking water increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension.” | Industry, Naturally Occurring |

| Both | Chlorate | “Chlorate forms in drinking water as a byproduct of disinfection. Chlorate impairs thyroid function, making chlorate exposure most harmful during pregnancy and childhood.” | Industry, Agriculture, Treatment Byproducts |

| Newark Water Source | Cyanide | “Cyanide is a toxic chemical that causes central nervous system and thyroid toxicity. Water contamination is generally the result of metal mining and chemical industry waste, runoff from agriculture and road salts used for melting ice.” | Industry, Agriculture, Runoff & Sprawl, Naturally Occurring |

| Both | Strontium | “Strontium is a metal that accumulates in the bones. Radioactive strontium-90 can cause bone cancer and leukemia, and any form of strontium at high doses can harm bone health.” | Industry, Naturally Occurring |

| Elizabeth Water Source | 1,4-Dioxane | “1,4-Dioxane is a solvent classified by the EPA as a likely human carcinogen. It contaminates groundwater in many states due to industrial wastewater discharges, plastic manufacturing runoff and landfill runoff.” | Industry. Runoff & Sprawl |

The intensity of development places Elizabeth in a higher proximity to risk management plan (RMP) facilities than other areas in the state and puts the residents at risk. These facilities use extremely hazardous substances and are thus required to have a risk management plan.[28] Elizabeth ranked in the 95th percentile in both the state and country for RMP Proximity. The usage of dangerous chemicals classified established industries around the Turnpike as RMP facilities. The hazardous environment and high risk of chemical accidents impact the population of mostly minorities, a concern that is not present for those living in wealthier areas with the absence of a highway through their town and thus absence of a heavy industrial presence.

Elizabeth Fights Back

The disparities of access to basic needs and rights of clean air and water between areas of different racial and socio-economic and racial backgrounds are clear to communities impacted. In Elizabeth there are strong organizations that are working to protest and change the environmental dangers residents face. Daniella Rivera described the stark contrast in quality of life within Union County: “The truth is that there are two completely different realities going on within Union County. I grew up in Elizabeth, where I thought it was normal to see factories producing smoke into our air 24 hours a day, or that it was okay to not be able to drink from our school’s water fountains due to the ongoing water crisis in Newark. I was fortunate enough to get accepted into a school like the Academy for Performing Arts, however the vast difference of the quality of life between myself and my peers shocked me.”[29] Environmental issues impact basic daily necessary activity like drinking water. Areas that are not as developed as Elizabeth do not have to deal with the congestion and constant fumes from cars and factories.

The fumes are a clear sign and reminder of the pollutants going into the air and impacting the climate. They are also a constant visual presence to young students like Daniella that the air they are breathing is not clean and not safe. It is a reminder to those with health issues they need to be careful because conditions can be exacerbated by the weather. The residents of Elizabeth are burdened with lower quality living and limited access to basic necessities, such as drinking water. The industry that encompasses this community is not merciful. It wreaks havoc on their society.

As my knowledge surrounding environmental issues expands, I experience daily activities differently. My commutes and car trips lead to internal questioning of the necessity of never-ending construction on every other highway. Traffic never seems to change despite changes in the highway yet that seems to be the only solution acceptable to alleviate congestion.

Recently, conversations happened about the proposal to dedicate billions of dollars to the expansion of the NJ Turnpike and Parkway. Many people and organizations rallied against this and protested the urgency placed on this highway project especially during a pandemic. Reporting on this issue faded a few months later and the plans seem fully intact to continue expansion on these two highways.

A highway is a contract for industry; it signs up an area to be the new center of development, which can cause negative impacts on cities, as was the case with Elizabeth. The repercussion to this level of construction, commuting, and consistent growth leads to great impacts on the land and residents of the area. Understanding this relationship can help with discussions and protests. More research can help give better understanding of root problems which instead of trying to heal in the future, we can avoid and do better in the present.

A lot of people are taking small steps to reduce their own personal waste, but corporations are contributing a great amount of pollution in ways that are both environmentally and racially unjust. The highway acts as a domino, it is the first piece that brings pollution, but once the building of a highway is approved it knocks down the potential for the area to be preserved as industries fall in line to exist near the highway. The protest of highways has not had a high rate of success for communities of color because communities are ignored for plans that are more convenient or profitable. Government money shows where the priority lies through the allocation of funds. In terms of cost, transportation is the second highest expense after housing for Americans. The federal funds for transportation are split 80% dedicated to highways and only 20% to public transportation. Bullard contrasts these numbers to the 24% of African American and 17% Latino households who do not have a car versus only 7% percent of white households who do not have access to a car.[30] Consistently, statistics show the unfair advantage and even burden that is placed on communities of color by the highways and the pollution and hazards they are exposed to. Recognizing these issues for the injustices they are is a first step in working to fund projects and policies that will benefit the environment and the residents living in heavily industrialized areas.

[1] Yergin, Daniel. Essay. In The Prize the Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power, 535. London: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

[2] ““Productivity and the Highway Network:” U.S. Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/otps/060320b/.

[3] Shatz, Howard J. “The Effects of Highway Infrastructure on Economic Activity.” Essay. In Highway Infrastructure and the Economy: Implications for Federal Policy, 23. Santa Monica, Calif: Rand Corporation, 2011.

[4] Karas, D.. “Highway to Inequity: The Disparate Impact of the Interstate Highway System on Poor and Minority Communities in American Cities.” (2015).

[5] PeriscopeFilm. “NEW JERSEY TURNPIKE SUPER HIGHWAY 1950s NEWSREEL 74752.” YouTube. YouTube, July 20, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSRhEJc3GHw.

[6] Newark Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), November 26, 1949: 12. NewsBank: Newark Star-Ledger Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-166C79E96E873C2B%402433247-166BC704FB7AEEB7%4011-166BC704FB7AEEB7%40.

[7] Newark Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), March 2, 1950: 7. NewsBank: Newark Star-Ledger Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-166E01E5DC42DB4B%402433343-166BD334F30E0775%406-166BD334F30E0775%40.

[8] “MAYOR, ETC., ELIZABETH v. NJ Turnpike Authority, 72 A.2d 399, 7 N.J. Super. 540.” CourtListener. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/2386679/mayor-etc-elizabeth-v-nj-turnpike-authority/.

[9] Karas, D.. “Highway to Inequity: The Disparate Impact of the Interstate Highway System on Poor and Minority Communities in American Cities.” (2015).

[10] “All United States Data.” Social Explorer. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.socialexplorer.com/a3bd60043a/view.

[11] “U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Elizabeth City, New Jersey.” Census Bureau QuickFacts. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/elizabethcitynewjersey.

[12] IBID

[13] Jeff Goldman | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. “You Have to Make This Much to Afford a Typical 2-Bedroom in N.J.” nj, June 9, 2017. https://www.nj.com/news/2017/06/a_typical_nj_resident_needs_to_make_this_much_to_a.html.

[14] PeriscopeFilm. “NEW JERSEY TURNPIKE SUPER HIGHWAY 1950s NEWSREEL 74752.” YouTube. YouTube, July 20, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSRhEJc3GHw.

[15] Newspaper 9/17/1945 advantages of newark airfield told.

[16] Schlenker, Wolfram, and W. Reed Walker. “Airports, Air Pollution, and Contemporaneous Health.” Accessed December 11, 2020. http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~mcmillan/s_and_w_2016.pdf.

[17] Garrity, Christopher. “Get Maps.” USGS Topoview. U.S. Geological Survey. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/topoview/viewer/.

[18] Ibid

[19] Google Maps. “Elizabeth, NJ.” Accessed December 11, 2020

[20] Vicki Hyman | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. “How 3 Planes Crashed in 3 Months in Elizabeth in ’50s.” nj, May 29, 2015. https://www.nj.com/entertainment/arts/2015/05/how_three_planes_crashed_in_elizabeth_in_50s.html.

[21] Martin, Antoinette. “Why Dumps Are Gaining in Allure.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 30, 2008. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/30/realestate/30njzo.html.

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Shopping Mall Pollution.” Environmental Pollution Centers. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.environmentalpollutioncenters.org/shopping-mall/.

[24] Ibid.

[25] EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

[26] Group, Environmental Working. “EWG Standards for Drinking Water Contaminants.” EWG Tap Water Database. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/ewg-standards.php.

[27] Group, Environmental Working. “EWG’s Tap Water Database: What’s in Your Drinking Water?” EWG Tap Water Database. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/system.php?pws=NJ2004001.

[28] “Risk Management Plan (RMP) Rule Overview.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, April 4, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/rmp/risk-management-plan-rmp-rule-overview.

[29] “Student Environmental Activists Rally For Environmental Justice in Elizabeth.” TAPinto. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.tapinto.net/towns/elizabeth/sections/green/articles/student-environmental-activists-rally-for-environmental-justice-in-elizabeth.

[30] Bullard, Robert D. “All Transit Is Not Created Equal.” Race, Poverty & the Environment 12, no. 1 (2005): 9-12. Accessed December 12, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41555221.

Primary Sources:

Google Maps. “Elizabeth, NJ.” Accessed December 11, 2020

Comparison of today’s current map to previous ones of the city will provide insight to how much the landscape has changed.

PeriscopeFilm. “NEW JERSEY TURNPIKE SUPER HIGHWAY 1950s NEWSREEL 74752.”YouTube. YouTube, July 20, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSRhEJc3GHw .

This informative video was published after the creation of the Turnpike and discusses the decision and costs it took to build the highway.

“MAYOR, ETC., ELIZABETH v. NJ Turnpike Authority, 72 A.2d 399, 7 N.J. Super. 540.”CourtListener. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/2386679/mayor-etc-elizabeth-v-nj-turnpike-authority/

The official decision of the courts in regard to Elizabeth suing the Turnpike Authority on grounds that they were violating the citizens rights.

Newark Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), November 26, 1949: 12. NewsBank: Newark Star-LedgerHistorical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-166C79E96E873C2B%402433247-166BC704FB7AEEB7%4011-166BC704FB7AEEB7%40 .

Newark Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), March 2, 1950: 7. NewsBank: Newark Star- Ledger Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX- NB&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-166E01E5DC42DB4B%402433343-166BD334F30E0775%406-166BD334F30E0775%40

Analysis of different newspaper articles will provide information on how information of the highway was perceived and discussed in the news. This will also provide a timeline for meetings and public forums that were held.

Secondary Sources:

EmpowerNJ’s Comments to the New Jersey Turnpike Authority’s Proposed Capital Plan. PDF file.

There are activist groups who are opposing the proposed plan to expand the NJ Turnpike. Empower NJ’s Steering Committee published its comments on why the expansion will not be effective and what alternatives could be more beneficial and better for the environment. I want to use this to analyze what environmental groups’ stances are and how they are voicing their concern to the government. It will help frame my paper and research around who is advocating for this project and how the government is responding to these concerns.

Finger, Matthias, and Maxime Audouin. 2019. The Governance of Smart Transportation Systems : Towards New Organizational Structures for the Development of Shared, Automated, Electric and Integrated Mobility 1st ed. 2019. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96526-0

This book discusses transportation systems in places across the world. I can use this source to better understand the scholarship around alternatives to highways. There is a commitment of billions of dollars to expand the New Jersey Turnpike including the expansion of bridges on the highway. I will use this reading to better understand how the money can be used for other things, potentially public transportation or making certain modes of public transportation free.

Plowman, E. G., and E. A. Imhoff. “INEVITABLE COMPROMISE: HIGHWAYS VS. THE ENVIRONMENT.” Traffic Quarterly 26, no. 2 (1972).

This article discusses economic and ecological factors of building highways. This source can help me better understand how ultimately money drives where highways are built. This article discusses the need for environmental scientists and engineers to be a part of the process and that compromises need to be made in order to prevent major environmental impact. I will also analyze how much change has been made since this article has been written and how much environmental consideration is made today when building roads and infrastructure.

Scheidt, Melvin E. “Environmental effects of highways.” Am Soc Civil Engr J Sanitary Eng Div (1967).

This source provides in depth information about the impact of the construction of highways on plants, animals, and the soil. It covers various aspects of the environment and how they can all be impacted during the construction of a highway and have long term effects. This can help me apply that information to the time they are projecting it will take to expand on the NJ Turnpike and how many miles they plan to cover. It will help me analyze the extent of the effects that may arise from the expansion of the highway and consider what if any impacts it could have outside the immediate area of the highway.

Wells, Christopher W. 2012. Car Country: An Environmental History Seattle: University of Washington Press.

In this book the author discusses how car dependency is a relatively new relationship in history. Wells challenged the ideas of dependency on automobiles and analyzes how it has impacted the United States’ landscape. With this reading I can better understand the relationship between cars, the environment, and creation of highways. It can help me build a better argument around the necessity of the expansion of the NJ Turnpike by having a better understanding of the changing roles of automobiles in the U.S.

Image Analysis:

Data Analysis:

The impacts from the NJ Turnpike are several and the people who live near this major highway face continuous effects to their lives and health. The city of Elizabeth was cut through to build the NJ Turnpike. In the process several homes were destroyed displacing approximately four hundred and fifty families. Properties were bought around the city to rent out the spaces to those who were displaced. Currently, there is public housing near the highway. In this analysis I will examine the current impacts of the highway on the residents living near it in Elizabeth, NJ.

Figure 1

The population of Elizabeth, NJ is 64.5% Hispanic or Latino according to the most recent Census data shown in figure 1 above. The second largest group is White, alone at 45%, but that is categorized as “A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as “White” or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Arab, Moroccan, or Caucasian.”[1] This definition does not give an accurate breakdown of the population. However, the data also shows that the foreign-born population between 2014-2018 is 46.2%. This points to a larger immigrant population than the percentage of White may suggest. Census data also shows that of the total population, 129,216, 18.6% of them are in poverty and the median household income (in 2018 dollars) 2014-2018 was $46,975. According to data from 2017, the average income to afford a two bedroom was $56,810 and a one bedroom was about $46,619. However, according to the census data there are about 3.12 persons per household, 2014-2018. This means that most people have others living with them and can barely afford a one bedroom. The data shows that “minimum-wager earners in New Jersey would have to work a whopping 106 hours per week to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment at the fair market rent of $1,165 per month.”[2] The struggles of the residents in Elizabeth are also highlighted by the statistic that persons without health insurance, under age 65 years, is 23.9%. Without health insurance, people are more reluctant to receive medical attention and when they need to it can result in enormous debts. Overall, the demographic points to a large minority group in the lower economic bracket.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides an environmental justice mapping and screening tool with data that exhibits information using an EJ index which is a combination of demographic data and environmental data. This information reveals that Elizabeth’s traffic proximity and volume is in the 94th percentile in both the state and country. The city’s index for Hazardous Waste Proximity is in the 90th percentile for New Jersey and the 95th percentile in the U.S. Additionally, Elizabeth ranks very high in the index for “Wastewater Discharge Indicator” at 97th percentile for the state and 95th percentile in the country. The data points to different sources for air and water pollution in the area. These findings are not surprising considering how developed the city is compared to others surrounding it. Figure 2 below shows a map of Elizabeth as one of the most developed areas of land in the state. The high intensity of development also places it in proximity to risk management plan (RMP) facilities. These facilities use extremely hazardous substances and are thus required to have a risk management plan.[3] Elizabeth ranked in the 95th percentile in both the state and country for RMP Proximity.

Figure 2

People are seeing the differences between their community versus the wealthier communities. In Elizabeth there are strong organizations that are working to protest and change the environmental dangers residents face. Daniella Rivera described the stark contrast in quality of life within Union County: “The truth is that there are two completely different realities going on within Union County. I grew up in Elizabeth, where I thought it was normal to see factories producing smoke into our air 24 hours a day, or that it was okay to not be able to drink from our school’s water fountains due to the ongoing water crisis in Newark. I was fortunate enough to get accepted into a school like the Academy for Performing Arts, however the vast difference of the quality of life between myself and my peers shocked me.”[4] Environmental issues impact basic daily necessary activity like drinking water. Areas that are not as developed as Elizabeth do not have to deal with the congestion and constant fumes from cars and factories.

Highways are a major Environmental injustice that thousands of people travel and pass through everyday not giving it much thought. Areas that are more secluded benefit from not even having to hear the noise that comes from highways. But the reality for those who do live beside a highway are there are many risks to the population’s health and ones that may not be evident yet.

[1] https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/elizabethcitynewjersey

[2] https://www.nj.com/news/2017/06/a_typical_nj_resident_needs_to_make_this_much_to_a.html

[3] https://www.epa.gov/rmp/risk-management-plan-rmp-rule-overview

[4] https://www.tapinto.net/towns/elizabeth/sections/green/articles/student-environmental-activists-rally-for-environmental-justice-in-elizabeth

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

This video story introduces the history of the building of the NJ Turnpike and gives a broad overview of the impacts it had on the city of Elizabeth, NJ. Highways are sources of environmental injustices and community members are actively fighting the dangerous health hazards that arise from highway. Elizabeth is a case study into how highways change the fabric of a city and cause great environmental disasters that disproportionately affect the health and well being of people of color.