“Get the Frack Out”:

Environmental and Economic Implications of Hydraulic Fracturing in Bradford County, PA

by Roy Samuel

Site Description:

The Marcellus Shale is a region that extends as far north as upstate New York, through Pennsylvania to West Virginia, and as far west as Ohio. Specifically, I intend to focus on Bradford County, PA between the year 2005, which was when the use of fracking to extract shale gas increased dramatically, and 2015, where legislation has slowed down the growth of these sites under Governor Tom Wolf. This county has six well operators, 765 violations of legislative policy, and 1,097 wells. Those involved include the residents of Bradford County, as well as several well operators, such as Chesapeake Appalachia LLC and Talisman Energy USA Inc. Generally, the Marcellus Shale region has sedimentary rock buried many feet beneath the Earth’s surface. Natural gas has built up over time in this area due to the process of decomposition. Therefore, to access that natural gas, the process of hydraulic fracturing, wherein water, sand, and other chemicals are injected into rocks at a high pressure, has become common. Some of these potentially carcinogenic chemicals can escape and contaminate groundwater near the site.

Final Report:

In 2010, Sheila Russell escaped her previous life working in a catalog company in Cheyenne, Wyoming, to return to the same plot of land in Bradford County, Pennsylvania that her family had settled back in 1796. She began to expand upon their maple syrup shop and delve into the world of organic farming, planting a wide variety of different vegetables and herbs. With her father, she successfully started the “Russell Sprouts Farm.” Like many other farmers in the region, Sheila’s family had gradually leased out mineral rights from their property for decades. Nobody had expected that any projects would actually be developed on their land. Regardless, Sheila’s dreams were gradually becoming a vivid reality.

This new lease on life was disrupted in June 2010, when Chesapeake Appalachia LLC (a subsidiary of the Chesapeake Energy Corporation) drilled two shale gas wells on their property. Initially, the family was not worried at all. If anything, they were excited, since they were promised a portion of the royalties if the wells began to produce, income that would go a long way in expanding their farm. However, Sheila was unaware that a cement casing on one of the hydraulic fracturing wells had failed upon installation. The Russells were finally notified of this issue after a year, and their neighbors had already been suffering adverse health conditions from water contamination. Sheila no longer drinks from her private well, and she has seen a decrease in her customers who cross over from New York for fresh produce. For her, fracking had already taken its toll, both environmentally and economically.[1] For more information on Sheila Russell’s story, and for a general overview of fracking in Bradford County, please refer to a four-minute video story that I made:

Sheila’s story is one that is shared by so many farmers living in Bradford County. Before 2007, this county was emblematic of an idyllic countryside, with sweeping hills flecked with hay bales and red barns.[2] Due to its central location and availability of vast plots of lands, through the decades, dairy farming, had become indispensable for the region.[3] However, as early as 2006, low milk prices began to put these dairy farmers out of business.[4] In the face of limited economic opportunities, the county was beginning to experience a “brain drain” of sorts, as younger residents left their ancestral farmlands to find jobs elsewhere.[5] Residents of the county needed a miracle solution to the impending economic devastation that was beginning to materialize.

That miracle solution presented itself in 2007, when Chesapeake Energy and other corporations began to frack in the county. Natural gas buried thousands of feet below the surface was seen as the economic boon that the county so desperately needed. Since the practice began in the area, 1,097 wells were created. With those wells came 765 violations of environmental policy.[6]

The economic state of Bradford County before fracking immediately begs the question: did fracking work? What impact did its onset have on residents economically? All of the environmental violations also seem to suggest even more questions. Has the community experienced adverse health effects? How have companies persisted in the area in spite of all of the repeated violations they have perpetrated?

In order to answer these questions, we need to review what economic and environmental promises were made by Chesapeake Energy to the residents of Bradford County in regard to fracking. We also must learn how those promises were reneged on both fronts. Through a comparison between fracking in Bradford County and Butler County, a relatively wealthy county within the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania, I intend to discuss why Bradford County itself has continued to deal with these repeated environmental violations. Finally, it is also valuable to understand how the community has begun to organize to resist these actions. Despite the portrayal of fracking as economically stimulating and environmentally safe, the experiences of the residents suggest that this practice has had environmental and economic ramifications. These generally low-income residents have been targeted by these companies and have begun to unite as a community in response to these practices. This issue can be framed within the context of environmental injustice in the postwar period, since many isolated, low-income, rural communities will soon have to address similar impacts of the extraction and utilization of natural resources.[7]

Before understanding how the economic and environmental promises to the residents of Bradford County have been broken, we must first understand what exactly those reassurances were.

The Economic Promises and Environmental Reassurances of Chesapeake Energy

Bradford County is situated directly on the Marcellus Shale, a region organically rich in black shale that extends as far north as upstate New York, through Pennsylvania to West Virginia, and as far west as Ohio. Buried deep underneath the surface is sedimentary rock. Due to the process of decomposition, natural gas has built up in this area. In order to access that natural gas, the process of hydraulic fracturing, also known as “fracking,” is undertaken. In this process, water, sand, and other chemicals, which are often unspecified to much of the public, are injected into rocks at extremely high pressures.

One of the first well operators to pounce on this opportunity in 2007 was Chesapeake Appalachia, a subsidiary of Chesapeake Energy. Within just a few months, the corporation had purchased nearly two million acres of land. Farmers in the county began to lease out the mineral rights of their lands, not expecting any development to actually occur there; consequently, two thousand and eighteen gas leases between Chesapeake Energy and property owners in the county were recorded in 2008.[8]

Chesapeake Energy convinced residents of Bradford County that hydraulic fracturing would bring heightened economic success to the region through the creation of more jobs. An executive director from within the corporation and the executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of Pennsylvania estimated that the fracking for natural gas would add approximately 100,00 new jobs.[9] With all of these new opportunities, politicians in the region agreed that these new jobs would cause more youth to stay home, and consequently called for less stringent regulations of fracking in the county.[10] In a town hall meeting in Wysox Township, a Chesapeake official claimed that there was no better place for drilling than Bradford County. He also stated that despite low prices for natural gas at the time, the prices would not only go back up, but also remain stable for a long time – “that’s bullish for Bradford County.”[11] To further curry favor among both residents and politicians alike, Chesapeake Energy made donations to local organizations in the county, including a $25,000 donation to the Partners for the Future Capital Campaign of the Bradford County Regional Arts Council.[12] With this influx of new jobs, revenue, and promises of retaining youth, one local commissioner testified that fracking was on pace to be “the most significant economic impact presented to county.”[13]

These economic incentives extended beyond more jobs: farmers faced with falling milk prices and reduced agricultural output would receive valuable royalty payments for leasing their lands to Chesapeake. One farmer in neighboring Susquehanna County leased his land to a company called Chief Oil and Gas. He recalls that since the drilling rigs were implemented on his land, he felt at ease: “The bills are all paid. Your kid’s gotta go to college? No problem.”[14] As a result, farmers in Bradford County were enticed by the prospect of financial security offered to them by Chesapeake Energy. Mutual agreements between energy companies and politicians were manifested through legislation that guaranteed that royalties worth at least one-eight of value of natural gas production would be given to the property owner.[15] All in all, there was a sense of excitement that this new incoming flow of money to landowners through leases and royalties was going to re-stimulate a fading agricultural economy.[16]

The need to frack was also framed as an aspect of national duty to reduce dependence of foreign oil. Local politicians took on this rhetoric from Chesapeake Energy when addressing residents to convince them of the surprisingly important role that they could each play to that purportedly noble end.[17] One local dairy farmer attended a presentation by a Chesapeake representative at Penn State University who implored residents to sacrifice: “it was our patriotic duty to assure our Country would be independent from foreign oil.”[18]

Environmentally, Chesapeake convinced residents that fracking was safe. Part of that promise is evident in the way the corporation presented themselves: as a reputable and environmentally responsible business. In a town hall meeting with residents, one representative from the company assuaged their apprehension concerning environmental degradation by stating that Chesapeake was a business that “enjoys a fine reputation in the industry for doing the right thing to be good neighbors in the exploration and extraction of the energy resource.”[19] Moreover, in a local news segment, Chesapeake justified its rapid increase in well production by claiming that it has high safety standards.[20] These assertions were an integral component of the promises made by the corporation since it established a preliminary bond of trust between residents and well manufacturers.

There were also reassurances that the extremely complex process was safe due to its implementation by professionals. Chesapeake’s own description of the process states that the wellbore designs are meticulously engineered to prevent the migration of hydrocarbons and fluids into groundwater. Furthermore, they claim that every well is continually monitored by both a team present at the well site and a team working from the Operations Support Center in Oklahoma City. [21] An official from the company also told residents that the process for receiving permits to install injection wells is very rigorous, only allowing for the utmost precision in their design and structure. As a result, when asked if the injection wells could be harmful to the environment, he claimed: “I think they are safe.”[22]

When addressing the potential environmental concerns of residents, Chesapeake Energy also claimed that the hydraulic fracturing process itself was pristine. A representative to the company told residents at a town hall that fracking is “unbelievably clean,” especially when compared to other means of natural resource extraction. He elaborated, by claiming that fracking gives off only half of the carbon dioxide produced from coal extraction and takes far less water as well.[23] Another Chesapeake official, when asked about potential groundwater contamination, scoffed at the idea, stating that it was unlikely that water left behind from the process could contaminate groundwater since it would “have to travel upward at least a mile through rock.”[24] However, the environmental reality for the residents of Bradford County was in stark contrast with these reassurances: fracking had devastating environmental impacts on the residents of Bradford County.

Environmental Impacts of Fracking on Residents of Bradford County

The largest environmental ramification caused by fracking is undoubtedly water pollution. Despite the insistence of Chesapeake that groundwater could not be contaminated by fracking fluids, there is much evidence to the contrary. The water from three homes in Bradford County were sampled, and traces of a chemical called 2-butoxyethanol (a known carcinogen in mice) that is utilized in Marcellus Shale drilling was found.[25] The contamination stemmed from a faulty drill well. After the three families had filed a lawsuit, Chesapeake eventually settled, paying $1.6 million for the contamination, buying the homes from the families, and maintaining that the contamination did not stem from their drilling practices.[26] In another incident, a wellhead malfunction occurred during fracking, causing thousands of gallons of fracking wastewater to spew back up to the surface, eventually contaminating a nearby tributary to the Towanda Creek.[27] Farmers, like Sheila Russell, had their groundwater contaminated with methane due to faulty well casings. For some residents, like Sherry Vargson, so much methane has leaked into well water that the water itself has become flammable.[28]

Since the chemicals involved in the process are not divulged, studies have deciphered elevated levels of radium from Marcellus Shale samples, with some sites having radioactive material over two hundred times the amount than the safe drinking water limit permits.[29] The Environmental Protection Agency commissioned a study to test the drinking water from thirty-seven residents of Bradford County, and when its report was released, Chesapeake refused to accept the results. Instead, through a leaked internal correspondence, the company contacted the EPA, having commissioned their own study on fourteen residents’ drinking water, insisting that the EPA re-evaluate its claims and amend its study. Regardless of the results of this incomplete study by Chesapeake, extensive water pollution was undoubtedly a byproduct of fracking.[30]

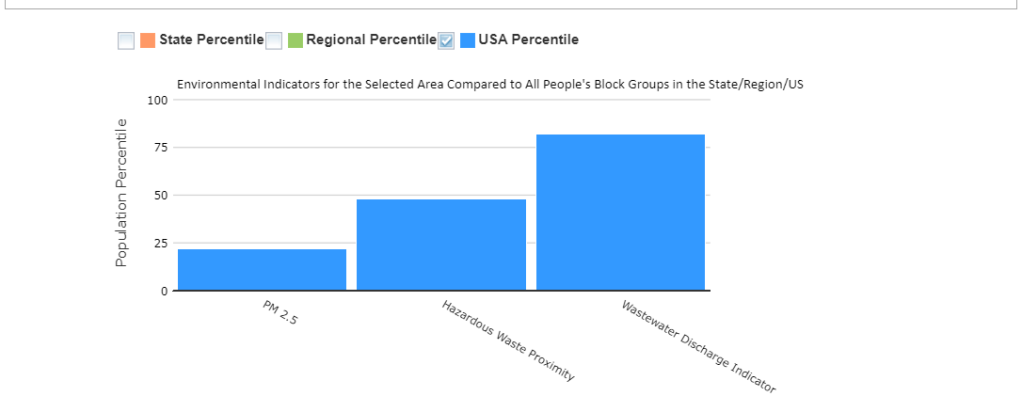

Using the EPA’s Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJSCREEN, I highlighted a particular zone of interest on a map of the United States, and retrieved environmental information related to this particular site.

Bradford County is in the forty-eighth percentile for proximity to hazardous waste management facilities. Perhaps this high count of Treatment Storage and Disposal Facilities (TSDF) is necessary to cope with the waste produced by hydraulic fracturing, such as fracking fluids. The increased number of these facilities, in simple statistical terms, increases the exposure of residents to the disposal and storage of hazardous wastes. The most revealing piece of environmental data is that Bradford County is in the eighty-second percentile for Wastewater Discharge Indicator. This number refers to the concentration of toxics in streams within five hundred meters divided by distance, in kilometers. The wastewater produced by fracking is laced with chemicals and radionuclides, and although it is initially pumped underground, it eventually flows out of the well as wastewater.

Fracking also had impacts on air pollution in Bradford County as well. Periodically, gas flares are released at fracking sites. In this process called flaring, excess gas is burned off, effectively releasing pollutants into the air depending on the gas being burned and the air’s temperature.[31] In addition, the support infrastructure required to implement the entire process of hydraulic fracturing requires increased pipelines, compressors, and trucking.[32] Increased truck traffic increased the amount of dust in the air, and the release of chemicals and other volatile organic compounds, such as benzene, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, and diesel exhaust, has accumulated to cause ground-level ozone in some cases.[33] Many of these chemicals are released throughout the drilling process, as well as during the subsequent storage and transport of natural gas afterwards.

Based on the same EJSCREEN data tool utilized earlier, I was able to see that the percentile for particulate matter levels in the air, measured in micrograms per cubic meter, was 22 (see above). Generally, particulate matter refers to liquid and solid particles suspended in the air; more specifically, PM2.5 refers to atmospheric particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers. The percentile does seem low initially; however, one would expect this number to be much lower in a rural area such as Bradford County, since rural areas tend to have less levels of air pollution than urban areas. For reference, Clark County in Wisconsin, the second largest dairy farming county in the United States, had a PM2.5 of 10, which is less than half of the percentile found in Bradford County.

The increases in levels of pollutions has led to adverse health impacts on residents. Carol French, a local dairy farmer, discusses her own personal struggles dealing with the aftermath of fracking: “My daughter became sick…with a fever, weight loss (10 pounds in 7 days), and severe pains in her abdomen. At the hospital they found her liver, spleen and her right ovary were extremely enlarged. My daughter moved out of the state…in order to have a chance of a healthy, normal life.”[34] There have also been many studies that detail just how much of an impact fracking has had on health outcomes for residents of Bradford County and those living in the Marcellus Shale region in general. Increased percentages of adverse childbirth outcomes, such as low birth weights, infertility, and preterm births have been observed.[35] Moreover, there has been a higher incidence of childhood cancer than the county had predicted.[36] Cancer rates have generally gone up, including increased instances of leukemia, as well as bladder, thyroid, and urinary cancer.[37] Due to increased particulate matter in the air, increased incidences of respiratory ailments as well as asthma have increased.[38] Fracking had a very real physical toll on the people living near these wells.

This toll extended beyond just the physical as well, even affecting mental and psychological wellbeing. Studies have been done on Marcellus Shale communities to observe how fracking contributes to disruptions in the residents’ social identity and sense of place. This disruption generates social stress.[39] In an ironic twist of fate, the heightened focus of fracking in these communities as a national obligation has led to a diminished perception of place locally. Specifically, in Bradford County, many residents have discussed how, in the midst of this rapid social and environmental transformation, they can barely recognize their homes. Here is one resident’s recollection of the environmental transformation that has come with fracking: “One of my favorite things in the whole world when you’re having a rough week is to go to [name of] Lake in my canoe and sit out there and fish, and I have a big, huge, loud, noisy well out there. It’s just amazing to me. That’s the part—I think sometimes it breaks my heart that the scenery has been just transformed.” Another resident, reminiscing about the past, says: “I love being in the woods, and it’s almost like ever since the industry came into the county, there’s just less woods around. The land is just pretty much gettin’ tore up. So to speak, they put it back, but it’s just there’s almost not the same feeling in the county as what there was 5, 6 years back.”[40] In the midst of all of these deleterious environmental impacts, fracking had severe economic impacts as well.

Economic Impacts of Fracking in Bradford County

All in all, Chesapeake Energy’s promises of economic stimulation largely went unfulfilled, going as far as having severe impacts on residents of Bradford County. However, there was limited economic success for a few. With the installation of about two thousand shale-gas wells, the economic benefits for companies like Chesapeake Energy, as well as larger leaseholders, has been very pronounced.[41] Between 2007 and 2010, total taxable income increased dramatically, close to nineteen percent. The majority of that increase pertained to compensation for leases and royalties, with mineral rights owners benefitting the most.[42] With the influx of workers from other states coming into Bradford County, local restaurant businesses also generally improved.[43] Although economic success was felt by a few, fracking as a whole tended to have a negative impact.

Residents of Bradford County were promised that 100,000 new jobs were going to be created due to the installation of hydraulic fracturing wells. While new jobs were undoubtedly created, it was only a modest increase in terms of the number of residents working jobs related to fracking. A significant percentage of these new jobs that were created went to non-residents or temporary commuters from other counties and even other states.[44] This influx of new workers in the county had a Boomtown effect, which refers to a rapidly increasing population in a small rural community with a limited capacity to meet those needs. These neighborhoods are marked by price inflation, overextended public services, and local rent and housing prices increasing.[45] Accordingly, the promise of job creation leading to further youth retention was also reneged: between 2005 and 2011, there was an eight percent decrease in net school district enrollment.[46] Moreover, when all of the costs associated with fracking, such as those related to health, environment, and community issues, are totaled, the final cost is estimated to be $16,836,000 annually.[47]

There were also serious issues related to the royalty payments that farmers in the county relied on to revitalize their farms in the midst of an economic downturn. One couple recalled their experience as they received a gross royalty payment of only $390 for several months of gas production. After all of Chesapeake’s deductions, the check they ended up receiving was for only $30.[48] Several leaseholders reported having up to ninety percent of their payments withheld, with countless others receiving checks for zero dollars. Moreover, other landowners were charged retroactively by Chesapeake in an attempt to recover post-production costs.[49]

Soon Bradford County commissioners had to travel to Harrisburg to meet with the governor, since they were “inundated with landowners, and friends and family of landowners who [felt] they are unjustly compensated for their royalties.”[50] However, they were discouraged from further pursuing a legislative fix to the issue, rather than just a one-time settlement payment, since the governor of Pennsylvania at the time, Tom Corbett, was having conversations with the CEO of Chesapeake and other gas companies, eventually coming to a solution that was “in the best interests of Oklahoma.” [51] To make matters even more difficult, a bill in the state House addressing the gas royalty controversy was stuck in committee, with no intention of ever being voted on. [52] The sense of excitement initially felt at the prospect of receiving royalty payments quickly dissipated, and this broken promise would later serve as a rallying cry for residents to voice their frustrations and fight back.

Fracking had also done irreparable damage to the agricultural backbone of the local economy. When Carol French was asked about the current state of her dairy farm, she said that her farm has lost ninety percent of its property value: “I’m losing my milk market and probably I won’t be able to sell my cows.”[53] In her neighborhood alone, there used to be twelve dairy farmers; now there are only three that have kept their farms running.[54] In Bradford County, between the years 2007 and 2011, total milk production declined, almost by 15.7 percent.[55] This trend is alarming and could potentially have a domino effect if the number of farms and agricultural activity fall too low, since essential supporting businesses would also be forced to leave.[56]

This sentiment was perfectly captured by a father talking about his three children’s futures in Bradford County: “I have three children that were all interested in pursuing agriculture…but when they saw the impacts to the gas drilling in the area overall a couple years ago, they said, dad, I don’t know if I really want to invest the rest of my life in this area. That was a huge blow…all of a sudden there’s this huge amount of traffic going on and it’s a huge impact to what you’re dealing with there…we’re going to have to live with this for a long time.”[57] It is evident that fracking had disastrous economic reverberations throughout this community. Bearing these economic and environmental implications in mind, we can shift towards understanding why these effects have been felt so dramatically in Bradford County.

Why Bradford County?

To answer this question, we need to start around 200 miles southwest of Bradford County in Butler County. This county is the seventh wealthiest in Pennsylvania and is defined as a rural county based on specific population parameters (namely a population density less than 284).[58] Using the EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, I was able to obtain some revealing demographic indicators for the county. It ranks in the thirty-third percentile for residents having less than a high school education, and in the thirty-fourth percentile for residents categorized as being low-income. Fracking does occur in this county: there are currently 321 active wells, with 57 recorded violations of environmental policy.[59] In summation, this population can best be described as well-educated, rather well off, and experiencing very few violations caused by fracking.

Out of the 64 counties in Pennsylvania, Bradford is 48th in terms of income. Using similar population parameters as before, the county is also categorized as rural.

The demographic indicators from the EJScreen data (see above) are extremely insightful: Bradford county is ranked in the fifty-fifth percentile in regard to the proportion of the population having less than a high school education and is ranked in the fifty-seventh percentile in terms of low-income residents.

There are 1,097 active wells in the county, with 765 violations of environmental policy.[60] If violations were occurring at the same rate in Butler County as they were in Bradford County, we would anticipate around 195 violations; instead, we have almost four times that amount. Bradford’s population is disenfranchised: the lack of higher education invariably places restrictions to economic and social mobility. This problem is further exacerbated by younger residents leaving, since the county has a substantial population over the age of 64 (in the seventy-sixth percentile nationally), effectively leaving the elder residents of the county alone with their failing farms. The fact that these residents are low-income reinforces their disenfranchised status, as both corporations and politicians alike do not consider them in their practices and decision-making, as seen in the stalled legislation to remedy the royalty losses felt by farmers. By comparing Bradford and Butler counties, one can see that the disenfranchised individuals of Bradford County are being exploited by companies like Chesapeake Energy. In the midst of these insurmountable odds, they have begun to fight back.

Residents of Bradford County Fight Back

In response to these environmental and economic consequences of fracking, the residents of Bradford County began to actively demonstrate. Seven hundred residents attended a meeting with state and local officials discussing a bill aimed at ensuring that gas companies pay fair royalties. In response to stalled legislation to amend the issue, the county announced that it was paying fifteen thousand dollars to a public relations firm to create a video in October of 2016. The film would detail the stories of landowners who feel that they are essentially being ripped off. Michael Caputo, a former Trump advisor, ran the campaign and helped produce the video. The video was intended to criticize gas driller Chesapeake Energy in order to push for a bill to be passed in the Pennsylvania General Assembly that would ensure that the residents received their royalty payments.[61]

This video below serves as a means of highlighting the sense of abandonment felt by everyday residents of Bradford County, and serves as a means of understanding both how hydraulic fracturing companies like Chesapeake Energy operate and how residents resist those occasionally duplicitous operations. Moreover, it emphasized the types of people who are directly affected by this practice: the independent, hard-working farmer who has an intimate relationship with the land, a figure given a sacred status throughout American history. Before I analyze specific aspects of this video, please take a look at its entirety:

The sense of abandonment as well as an agricultural element are supplemented by the contrast apparent between the two general zones of activity within the picture frame. All of the residents are in the foreground as they each recount their own experiences. By contrast, the background is filled with extensive landscapes, both farmed and natural, that appear absolutely still.

For example, as one hears Jim Barret (pictured above) discuss his story, one can discern that the farmland sweeping up and down the hills, as well as the mountains all the way in the back, remain absolutely still. This contrast between activity of the foreground and inactivity of the background engenders a feeling of loneliness, an almost ominous isolation. It also reinforces his unique connection with his land. This video marks the beginning of the residents of Bradford County banding together to resist the byproducts of fracking in their community.

Conclusion

Hydraulic fracturing in Bradford County, PA, consequently, is a matter of environmental justice, with disenfranchised residents being exploited for purported economic gain. Chesapeake Energy had initially made economic promises to residents, claiming that fracking would help create thousands of new jobs, retain youth in the county, stimulate the economy through royalty payments, and contribute nationally to mitigate the United States’ dependence on foreign oil. Environmentally, Chesapeake assured the community that the process was safe, implemented by professionals, and was a relatively clean process compared with other means of extracting natural resources.

Ultimately, each of these reassurances were proven to be false. Fracking contributed to increased water and air pollution, which have had ill effects on health outcomes for residents in the area. There have also been psychological effects related to disruptions in a regional sense of place. While a few benefitted from the practice economically, most of the residents suffered the effects of a Boomtown, with more of their youth leaving than previously. Many were also cheated out of their just compensation in royalties, while also dealing with a major overhaul of their local, agricultural economy. With these impacts in mind, we analyzed how the people in this county were targeted due to their disenfranchised socioeconomic status through comparing demographic indicators in Butler and Bradford Counties. We also saw how residents in the county have begun to counter Chesapeake Energy’s practices by creating a video imploring elected official to pass legislation so that they would receive their fair share.

This story is one that can be told within the context of environmental justice in the postwar United States. When the environmental justice movement began in the 1980s, it served as a reaction to “discriminatory environmental practices” that had negatively affected communities of color.[62] Presently, part of the focus of the movement has shifted to enable marginalized and vulnerable peoples to construct resilient and healthy communities, which includes isolated, low-income rural communities. A major issue that many rural regions will have to address pertains to the extraction and utilization of natural resources that has distinct environmental and prolonged economic impact. The experiences of the residents in Bradford County offer a protracted insight into how other communities can begin to overcome these concerns.

Notes:

[1] Information from this paragraph stems from: Dimitar Kenarov, “Pennsylvania: Of Veggies, Maples, and Shale Gas,” The Pulitzer Center, Published: February 1, 2013, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/pennsylvania-veggies-maples-and-shale-gas

[2] Dimitar Kenarov, “Bradford County, Pennsylvania: Fracking for Gas, Farming the Land,” The Pulitzer Center, Published: January 8, 2013, Accessed: April 8, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/bradford-county-pennsylvania-fracking-gas-farming-land#slideshow-7

[3] Sofia Ojeda, “The Future of Agriculture on Bradford County,” 16-WNEP, The News Station, Published: November 7, 2012, Accessed: April 15, 2020, https://www.wnep.com/article/news/local/bradford-county/the-future-of-agriculture-in-bradford-county/523-7a6db451-cb61-4c05-b836-d8d34d29bb5b

[4] Marcia Moore, “Dropping milk prices jeopardize dairy operations in U.S. and Valley,” The Daily Item (Central Susquehanna Valley, PA), Published: February 25, 2018, Accessed: May 5, 2020. https://www.dailyitem.com/news/dropping-milk-prices-jeopardize-dairy-operations-in-u-s-and-valley/article_9fc885a0-19eb-11e8-924f-4709a009fb43.html

[5] James Loewenstein, “McLinko urges board to not over-regulate local gas drilling.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: September 12, 2008, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/124B555152394C68.

[6] Chris Amico, Danny DeBelius, Scott Detrow, and Matt Stiles, “Shale Play: Natural Gas Drilling in Pennsylvania – Bradford County,” State Impact & npr, Published: 2011, Accessed: February 5, 2020. http://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/drilling/counties/bradford-county/’

[7] Barbara Wyckoff, Danyelle O’Hara, Michelle Mosher, Maia Enzer, and Chad Davis, “Rural Environmental Justice,” National Rural Assembly, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5134e05de4b060819b1457f8/t/51968bf2e4b0a695733a5bf1/1368820722252/EnviroJustice_Policy_Paper.pdf

[8] Jeff Goodell, “The Big Fracking Bubble: The Scam Behind Aubrey McClendon’s Gas Boom,” Rolling Stone, Published: March 15, 2012, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/the-big-fracking-bubble-the-scam-behind-aubrey-mcclendons-gas-boom-231551/

[9] The Review “Natural gas exploration emerging as area bonus.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: June 7, 2009, Accessed: April 10, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/128AE2E42BEC85A8.

[10] James Loewenstein, “McLinko urges board to not over-regulate local gas drilling.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: September 12, 2008, Accessed: April 7, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/124B555152394C68

[11] James Loewenstein, “Gas company official expects gas to be boon for county.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 17, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/127A144116171338.

[12] The Review, “25K donation made to arts council.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: February 25, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/12694FB828760070.

[13] The Review, “Mark Smith testifies on gas drilling Commissioner tells about economic impact in Bradford County area.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 11, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/127819505CE92368.

[14] Marie Cusick and Amy Sisk, “Millions Own Gas And Oil Under Their Land. Here’s Why Only Some Strike It Rich.” Special Series: Environment and Energy Collaborative, npr, Published: March 15, 2018, Accessed: May 1, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2018/03/15/592890524/millions-own-gas-and-oil-under-their-land-heres-why-only-some-strike-it-rich

[15] Eric Hrin, “Natural gas information offered.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: October 8, 2008, Accessed: April 11, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/124B554B5DCF2250.

[16] Editorial Section, “Assure no scars are left from gas extraction.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 19, 2008, Accessed: April 11, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/120278FB603B7700.

[17] James Loewenstein, “McLinko urges board to not over-regulate local gas drilling.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: September 12, 2008, Accessed: April 20, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/124B555152394C68.

[18] Carol French, “A Dairy Farmer Shares Her Story About Fracking: ‘What Have We Done?’” The Public Herald, Published: October 30, 2012, Accessed: March 15, 2020, https://publicherald.org/a-dairy-farmer-shares-her-story-about-fracking-what-have-we-done/

[19] The Review “Natural gas exploration emerging as area bonus.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: June 7, 2009, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/128AE2E42BEC85A8.

[20] Dave Bohman, “Chesapeake Energy’s Mixed Safety Record,” 16-WNEP, The News Station, Published April 21, 2011, Accessed: April 14, 2020. https://www.wnep.com/article/news/local/bradford-county/chesapeake-energys-mixed-safety-record/523-5d77f201-e321-479e-a272-39f6f2470cd2

[21] Chesapeake Energy, “Operations and Environmental Protections,” Accessed: April 30, 2020 http://www.chk.com/responsibility/environment/operations

[22] James Loewenstein, “Gas company official expects gas to be boon for county.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 17, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/127A144116171338.

[23] James Loewenstein, “Gas company official expects gas to be boon for county.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 17, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/127A144116171338.

[24] Christopher Joyce, “With Gas Boom, Pennsylvania Fears New Toxic Legacy,” Special Series: The Fracking Boom: Missing Answers, npr, Published: May 14, 2012, Accessed: April 15, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2012/05/14/149631363/when-fracking-comes-to-town-it-s-water-water-everywhere

[25] Nicholas St. Fleur, “Fracking Chemicals Detected in Pennsylvania Drinking Water,” The New York Times, Published: May 5, 2015, Accessed: March 15, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/05/science/earth/fracking-chemicals-detected-in-pennsylvania-drinking-water.html

[26] Susan Phillips, “Chesapeake to Pay $1.6 Million for Contaminating Water Wells in Bradford County,” State Impact & npr, Published: June 21, 2012, Accessed: April 15, 2020, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2012/06/21/chesapeake-to-pay-1-6-million-for-contaminating-water-wells-in-bradford-county/

[27] Laura Olson, “Pa. ponders penalties over Bradford County drilling site mishap,” The Times Leader (Wilkes Barre, PA), Published: April 25, 2011, Accessed: March 29, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/136DB4875B584650.

[28] “Fracking in Pennsylvania brings risks and rewards – in pictures,” The Guardian, Published: April 19, 2012, Accessed: April 14, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2012/apr/19/fracking-pennsylvania-in-pictures

[29] E.L. Rowan, M. A. Engle, C.S. Kirby, and T. F. Kraemer. “Radium content of oil- and gas- field produced waters in the northern Appalachian basin (USA) — Summary and discussion of data.” US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 5135 (2011)

[30] John Satterfield, “EPA Retrospective Study in Bradford County, PA – Weston Solutions Evaluation of Data” Chesapeake Energy Corporation, Published: May 17, 2012, Accessed: February 28, 2020, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/808165-chk-unable-to-perform-full-test-for-bradford.html

[31] “Fracking in Pennsylvania brings risks and rewards – in pictures,” The Guardian, Published: April 19, 2012, Accessed: April 14, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2012/apr/19/fracking-pennsylvania-in-pictures

[32] Dr. Mark Barkley, “The Economic Costs of Fracking in Pennsylvania,” ECONorthwest for the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, Published: May 14, 2019, Accessed: April 20, 2020, https://www.delawareriverkeeper.org/sites/default/files/ECONW-Costs_of_Fracking-May2019.pdf

[33] Dr. Mark Barkley, “The Economic Costs of Fracking in Pennsylvania,” ECONorthwest for the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, Published: May 14, 2019, Accessed: April 20, 2020, https://www.delawareriverkeeper.org/sites/default/files/ECONW-Costs_of_Fracking-May2019.pdf

[34] Carol French, “A Dairy Farmer Shares Her Story About Fracking: ‘What Have We Done?’” The Public Herald, Published: October 30, 2012, Accessed: March 15, 2020, https://publicherald.org/a-dairy-farmer-shares-her-story-about-fracking-what-have-we-done/

[35] LS Shaina, LL Brink, JD Larkin, Y Sadovsky, BC Goldstein, BR Pitt, and EO Talbott, “Perinatal

outcomes and unconventional natural gas operations in southwest Pennsylvania.” PLoS One 10: e0126425. (2015) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126425

[36] John Finnerty, “Scientist: ‘evidence is tipping’ about fracking damage,” The Daily Star (Oneonta, NY), Published: June 23, 2019, Accessed: April 20, 2020, https://www.thedailystar.com/news/scientist-evidence-is-tipping-about-fracking-damage/article_da6ec41c-788b-5497-aa85-6c986ca8d81c.html

[37] ML Finkel, “Shale gas development and cancer incidence in southwest Pennsylvania,” Public Health (2016) 141: 198-206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.09.008

[38] E Webb, J Hays, L Dyrszka, B Rodriguez, C Cox, K Huffling, and S. Bushkin-Bedient, “Potential hazards

of air pollutant emissions from unconventional oil and natural gas operations on the respiratory health of children

and infants.” Reviews on Environmental Health, (2016) 31(2):225-243. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2014-0070

[39] T Sangaramoorthy, AM Jamison, MD Boyle, DC Payne-Sturges, A Sapkota, DK Milton, SM Wilson, “Place-based perceptions of the impacts of fracking along the Marcellus Shale,” Social Science and Medicine (2016), 151: 27-37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.002

[40] All quotes taken from: Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/The-Marcellus-Shale-Impacts-Study.pdf

[41] Dimitar Kenarov, “Gas Boom, Farm Bust in Pennsylvania” The Pulitzer Center, Published: January 28, 2013, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/gas-boom-farm-bust-pennsylvania

[42] Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/The-Marcellus-Shale-Impacts-Study.pdf

[43] The Review, “Mark Smith testifies on gas drilling Commissioner tells about economic impact in Bradford County area.” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: April 11, 2009, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/127819505CE92368.

[44] Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/The-Marcellus-Shale-Impacts-Study.pdf

[45] “The Social Costs of Fracking: A Pennsylvania Case Study,” Food and Water Watch, Published: September 2013, Accessed: April 20, 2020, https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/Social%20Costs%20Fracking%20Report%20Sept%202013_0.pdf

[46] Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/The-Marcellus-Shale-Impacts-Study.pdf

[47] Dr. Mark Barkley, “The Economic Costs of Fracking in Pennsylvania,” ECONorthwest for the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, Published: May 14, 2019, Accessed: April 20, 2020, https://www.delawareriverkeeper.org/sites/default/files/ECONW-Costs_of_Fracking-May2019.pdf

[48] James Loewenstein, “Board to look into royalty check deductions,” The Daily Review and Sunday Review (Towanda, PA), Published: August 3, 2012, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/14070B5947188358.

[49] Colin Hogan, “Bradford County Commissioners sit down with governor to discuss royalty issues,” The Morning Times (Sayre, PA), Published: August 16, 2013, Accessed: April 13, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/16249E526289D7B8.

[50] Colin Hogan, “Bradford County Commissioners sit down with governor to discuss royalty issues,” The Morning Times (Sayre, PA), Published: August 16, 2013, Accessed: April 13, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/16249E526289D7B8.

[51] Warren Howeler, “Bradford County Commissioners continue fight on royalty issues,” The Morning Times (Sayre, PA), Published: September 6, 2013, Accessed: April 15, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/16249E58186E3238.

[52] Warren Howeler, “Royalties bill stuck in committee,” The Morning Times (Sayre, PA), Published: September 26, 2013, Accessed: April 10, 2020, NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/16249E60654DBA78.

[53] Dimitar Kenarov, “Gas Boom, Farm Bust in Pennsylvania” The Pulitzer Center, Published: January 28, 2013, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/gas-boom-farm-bust-pennsylvania

[54] Bill Dedman, “Disputes over environmental impact of ‘fracking’ obscure its future,” NBC News, Published: April 7, 2013, Accessed: April 15, 2020, http://investigations.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/04/07/17616990-disputes-over-environmental-impact-of-fracking-obscure-its-future

[55] Madelon L. Finkel, Jane Selegean, Jake Hays, and Nitin Kondamundi, “Marcellus Shale Drilling’s Impact on the Dairy Industry in Pennsylvania: A Descriptive Report,” New Solutions (2013) 23(1): 189-201, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2190/NS.23.1.k

[56] Dimitar Kenarov, “Gas Boom, Farm Bust in Pennsylvania” The Pulitzer Center, Published: January 28, 2013, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/gas-boom-farm-bust-pennsylvania

[57] Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/documents/reports/The-Marcellus-Shale-Impacts-Study.pdf

[58] “Rural/Urban PA”, The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, Accessed: April 26, 2020, https://www.rural.palegislature.us/rural_urban.html

[59] “Shale Play: Natural Gas Drilling in Pennsylvania – Butler County,” State Impact & npr, Published: 2011, Accessed: April 5, 2020. http://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/drilling/counties/bradford-county/’

[60] “Shale Play: Natural Gas Drilling in Pennsylvania – Bradford County,” State Impact & npr, Published: 2011, Accessed: February 5, 2020. http://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/drilling/counties/bradford-county/’

[61] Information from this paragraph stems from: Marie Cusick, “Bradford County releases video slamming Chesapeake Energy,” State Impact & npr, Published October 14, 2016, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2016/10/14/bradford-county-releases-video-slamming-chesapeake-energy/

[62] Barbara Wyckoff, Danyelle O’Hara, Michelle Mosher, Maia Enzer, and Chad Davis, “Rural Environmental Justice,” National Rural Assembly, Accessed: April 10, 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5134e05de4b060819b1457f8/t/51968bf2e4b0a695733a5bf1/1368820722252/EnviroJustice_Policy_Paper.pdf

Primary Sources:

Source 1:

“EPA Retrospective Study in Bradford County, PA – Weston Solutions Evaluation of Data” (2012) https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/808165-chk-unable-to-perform-full-test-for-bradford.html

This document was leaked from internal conversations between the EPA and Chesapeake Appalachia LLC. This particular company questioned the findings of the EPA in regard to the results from sampling thirty-seven residential drinking water sources in Bradford County. Chesapeake commissioned WESTON Solutions to collect only 14 samples, and assumed, from that significantly lower sample size, that these sources “do not appear to be impacted by Marcellus Shale natural gas drilling or production activities — including hydraulic stimulation.” This source is useful for multiple reasons. Namely, it could speak to the persistent presence of this particular company in the county despite numerous repeated violations: by coming up with its own insufficient data and publicly disseminating it, Chesapeake appears to be engaged in a campaign of misinformation that seeks to delegitimize authorized opinions on the matter.

Source 2:

“Commonwealth of Pennsylvania DEP in the Matter of Chesapeake Appalachia LLC Tuscarora, Terry, Monroe, Towanda, and Wilmot Townships, Bradford County” (2011)

This document is the settlement between Chesapeake Appalachia LLC and three families residing in Bradford County. It was for $1.6 million in damages and was the first case pertaining to Marcellus Shale contamination that did not include a non-disclosure agreement. This allowed the three parties to publicly talk about this incident. These residents had initially signed leases with Chesapeake Appalachia to drill beneath their land. However, muddy water began to flow from their water wells. The company provided a filtration system, but, according to the three families, the system did not work. As a result, methane migrated from the Marcellus Shale region of drilling into the water supply of nearby residents. This source is useful, because it represents a break from the previous trend: what specifically about this case was successful in removing the nondisclosure agreement between the residents and the company? The previous arrangements all had these agreements, allowing the company to continue its operation in areas where it continually violates policy. Moreover, this source was the first to suggest some sort of community activism in the area against fracking. This source may serve as a segue for more information about community-level organization.

Source 3:

“Bradford County releases video slamming Chesapeake Energy” (2016)

This newspaper source, as well as the video it contains, discuss a different issue related to hydraulic fracturing: the royalties that the landowners are entitled to. However, residents of Bradford County are criticizing Chesapeake Energy for cheating them out of that money. As a result, they are advocating for legislation to address this “royalty rip-off.” While this issue is not directly pertinent to my topic, I believe that the video serves as a revealing insight into the kinds of people who are affected. One of the individuals says: “Most of the small landowners who were seeing their deductions taken…they don’t have the ability to hire a lawyer.” This source can be utilized within my project in two ways. In one sense, it supports my argument that the persistence of these violations and the practice of hydraulic fracturing in this region is linked to the fact that it disproportionately impacts poorer residents who do not have the financial means to challenge it. Moreover, it also provides evidence to begin answering my question: How has the community responded, and has that response led to tangible reforms or conflicts with the well operators, the local and state government, or both? Very clearly through this source, it is evident that this video was made and sent to Pennsylvania elected officials as a means of advocating for change.

Secondary Sources:

Source 1:

Emily Clough, and Derek Bell, “Just fracking: a distributive environmental justice analysis of unconventional gas development in Pennsylvania, USA”, Environmental Justice Analysis, Volume 11(2), 2016

This source is an academic journal article that analyzes the types of people (whether they are low-income or minority residents) particularly affected by fracking in the Marcellus Shale region from the year 2005 onwards.

This paper will contribute to different preliminary sections of my paper in a variety of ways. First of all, it provides insight into the actual practices of fracking itself, and the “official” way (at least legislatively) in which certain sites are chosen, specific to the Marcellus Shale region. In this sense, it contains background information that I could use to introduce my readers to the practice of hydraulic fracturing, and a brief overview of the ways in which certain sites are chosen. More importantly, this paper is a study that offers a distributive environmental justice analysis, which considers this question: “Are there a disproportionate number of minority or low-income residents in areas near to unconventional wells in Pennsylvania?” It goes into more detail, further considering income distribution and the level of education in these areas as well. All in all, this paper will help me answer one of my questions posed in the site description: Why are communities in Bradford County, and similar neighborhoods throughout the Marcellus Shale Region, particularly selected as sites for hydraulic fracturing? It provides an administrative answer, as well as one that is more realistic and environmentally unjust.

Source 2:

Kathryn Brasier, Lisa Davis, Leland Glenna, Tim Kelsey, Diane McLaughlin, Kai Schafft, Kristin Babbie, Catherine Biddle, Anne Delessio-Parson, and Danielle Rhubart, “The Marcellus Shale Impacts Study: Chronicling Social and Economic Change in North Central and Southwest Pennsylvania,” The Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 2014

This source is a study undertaken by the Center for Rural Pennsylvania documenting the various changes socially and economically that have been felt throughout the Marcellus Shale region between 2005 and 2013.

I am really eager to utilize this source, because it provides a regional profile of the residents of Bradford County. It contains details about the population makeup of Bradford County before and after 2005, when a rapid expansion of hydraulic fracturing wells was undertaken; information about levels of education; the housing market, the youth and their experiences; economic details; and agricultural information. In essence, I believe that this source is more specific to Bradford County, whereas my first source is more concerned with the Marcellus Shale region as a whole. Moreover, this source addresses another one of my research questions posed in the site description: How has the community responded, and has that response led to tangible reforms or conflicts with the well operators, the local and state government, or both? It includes a compilation of personal accounts from people living in the county, and their response to the changes that they were experiencing. For example, one participant in the study discussed how they were taken advantage of:

“The other thing is, even if you have it in your agreement, like my father-in-law had it all worked out. They were gonna run the water pipeline around the edge of the field so it didn’t—and they just wore him down and wore him down and wore him down until he’s finally like, fine. Put the water line through the center of the field. Because they—that was the easiest way for them. It didn’t matter that it was gonna be a management nightmare for the farmer.”

It also has accounts from farmers, local businesses, educational organizations, as well as health and housing agencies. I believe that this source is a good starting point for me to understand how the community responded, and, maybe, how they organized.

Source 3:

Garth T. Llewellyn, Frank Dorman, J. L. Westland, D. Yoxtheimer, Paul Grieve, Todd Sowers, E. Humston-Fulmer, and Susan L. Brantley, “Evaluating a groundwater supply contamination incident attributed to Marcellus Shale gas development,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005.

This source is an academic journal article that delves into the direct health impacts of fracking: the contamination of groundwater that can be directly imputed to Marcellus Shale gas development.

This source is relatively straightforward in its application to my project. It most directly addresses the question: How has fracking and its ramifications affected local communities in Bradford County in ways that extend beyond adverse health effects, especially among youth? It details the first part of the question, which pertains to the adverse health effects felt by the local community. The study confirms that drilling by Chesapeake Appalachia LLC in 2009 within Bradford County has led to the contamination of groundwater supply. The study itself is actually a chemical study, revealing that natural gas, as well as other organic contaminants stemming from fracking fluids, impacted an aquifer used as a source of potable water. These contaminants were discovered using methods and instrumentation that are not typically available in most laboratories. I accessed this scientific article from a primary source describing the study, which delves deeper into the roles that the EPA and Chesapeake Appalachia played throughout this whole scenario, as well as a brief historical overview.

Image Analysis:

“PA Royalty Rip-off”

The image I have chosen to analyze is a video from the residents of Bradford County in which they criticize Chesapeake Energy for allegedly cheating them out of royalty money. My chosen environmental site is the part of the Marcellus Shale Region that runs through Bradford County, Pennsylvania, which has six well operators, 765 violations, and 1,097 wells, between the years 2005 and 2015. This video suggests that these hardworking, middle-class, individuals affected by the practices of Chesapeake Energy feel forgotten, and even abandoned, by their elected officials. While it is not directly relevant to what I intend to focus on, this video, and what it conveys, are essential to understanding the nefariously persistent actions of these hydraulic fracturing companies, and how the community has responded to them.

After seven hundred residents attended a meeting with state and local officials discussing a bill aimed at ensuring that gas companies pay fair royalties, the county announced that it was paying fifteen thousand dollars to a public relations firm to create a video in October of 2016 detailing the stories of landowners who feel that they are being ripped off. (Ironically, those thousands of dollars came from gas royalties received by the county for leasing public lands). Michael Caputo, a former Trump advisor, ran the campaign and helped produce the video. The video was intended to criticize gas driller Chesapeake Energy, in order to push for a bill to be passed in the Pennsylvania General Assembly that would ensure that the residents received their royalty payments.

In one of the scenes of the video, Lois Neuber begins sharing her personal encounter with Chesapeake Energy that took place within her house. In that shot of her sitting in the dining room of her house, one is first drawn to Neuber herself, and then immediately to the white scrapbook sitting in front of her. The color of her scrapbook starkly contrasts with the dimly lit and rather dark surroundings of the rest of the room. The dimly lit background of the room, and the pronounced emphasis on the scrapbook containing images and memories from the past, suggests a feeling of isolation and even a sense of abandonment associated with the present situation. Moreover, as the focus of the viewer moves from the scrapbook to the rest of the room, a cluttered table is visible on the side. When shifting to the right, a case of china is also visible. These two elements evoke images of one’s own home: in a sense, they reinforce that the individual residing in this house is an ordinary person.

The sense of abandonment is supplemented by the contrast apparent between the two general zones of activity. All of the residents are in the foreground as they each recount their own experiences. By contrast, the background is filled with extensive landscapes, both farmed and natural, that appear absolutely still. For example, as one hears Jim Barret discuss his story, one can discern that the farmland sweeping up and down the hills, as well as the mountains all the way in the back, remain absolutely still. This contrast between activity of the foreground and inactivity of the background engenders a feeling of loneliness, an almost ominous isolation.

This idea is also evident as Joan Smith-Reese recounts her experiences. Although she is the director for an Animal Care Sanctuary, as she speaks, there are not any animals or general activity discernible in the background.

She is detached, and, by extension, forgotten.

Furthermore, there is an additional contrast that exists in terms of size and scale. Similar to the previous point pertaining to zones of activity, the contrast between the speakers and the immense landscapes that are behind them fortify the evoked sentiments of isolation and abandonment. For example, as Wayne Felder speaks, one is immediately drawn to the size and scale of the massive, forested mountain behind him.

In comparison to the hill, Wayne appears diminutive, and would be, from an aerial perspective, altogether absent. This observation seems to contest with the notion that larger size is correlated with greater importance; however, the individuals displayed in front of these towering natural phenomena as well as the ever-expansive breadth of farmed landscape are, in a sense, insignificant and inconsequential. They are easy to overlook.

This video serves as a means of highlighting the sense of abandonment felt by everyday residents of Bradford County, and serves as a means of understanding both how hydraulic fracturing companies like Chesapeake Energy operate and how residents resist those occasionally duplicitous operations. Moreover, these ideas display how communities in the postwar era in the United States have taken it upon themselves to redefine issues of environmental inequality and frame the discussion around disparities that exist alongside class distinctions.

Data Analysis:

The specific focus of my project is on the implementation of hydraulic fracturing along the Marcellus Shale region in Bradford County, PA, which has six well operators, 765 violations, and 1,097 wells. Companies, such as Chesapeake Appalachia LLC, continue to violate local regulations, and more areas within the county are being utilized as fracking sites since its residents are mostly low-income. Using the EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, I highlighted a particular zone of interest on a map of the United States and retrieved both demographic and environmental information related to that particular site, as well as 2010 Census information. Using the option to draw a site and altering the base map to the Streets (Night) option, I was able to outline my site along the border of Bradford County (Figure 1).

Figure 1: EJSCREEN Generated Map of Bradford County

Through this data, I intend to understand who was affected by the practice (based on demographic data), how they were affected (based on environmental data), and how these data together demonstrate that these residents are being targeted for the utilization of hydraulic fracturing on their land.

Figure 2: Demographic Indicators for Bradford County, PA

The demographic indicators and information garnered are percentile rankings in the United States. This information provides an insight into who is directly impacted by the practice of fracking in the county (Figure 2). The population residing in Bradford County is mostly white, with the minority population resting at the ninth percentile (in other words, 91% of the rest of the United States has a higher percentage of minorities in the population). Here, percent minority is calculated as a fraction of the entire population, and minority is defined as any ethnicity excluding Non-Hispanic White Alone. For more information about the exact definitions of each of these terms, and how some of these numbers are calculated, please reference this glossary of EJSCREEN terms: https://www.epa.gov/ejscreen/glossary-ejscreen-terms.

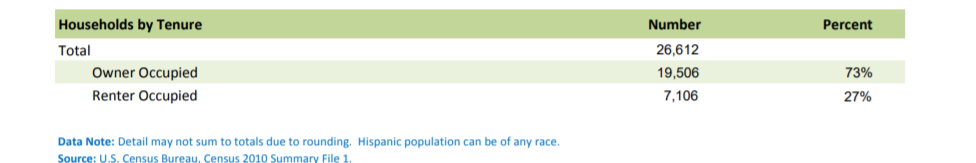

Moreover, the residents of the county are mostly low-income as well, ranking at the fifty-seventh percentile. Similarly, most of the residents have attained less than a high school education, ranking at the fifty-fifth percentile. According to 2010 Census information (Figures 3 & 4), Bradford County has a population density of 57 (population per square mile), with approximately seventy-three percent of residents owning their own houses and land, as opposed to renting it; together, the low population density and the high percentage of land ownership confirm that this county is relatively rural, and perhaps very much rooted in agriculture.

Figure 3: Population Information from the US Census Bureau

Figure 4: Housing Information from the US Census Bureau

The most glaring piece of demographic information is that this county is ranked at the seventy-sixth percentile for the population of individuals who are over the age of sixty-four. In summary, most of the affected residents are white, rural, low-income, not college educated, and over the age of sixty-four.

The environmental indicators here, again measured as percentile ranking in the United States, should be associated with those environmental risks of hydraulic fracturing, namely the contamination of ground and surface water, general air pollution, emissions of methane, and the migration of chemicals and other gases to the surface (Figure 5). The data does suggest this association.

Figure 5: Environmental Indicators for Bradford County, PA

Firstly, the percentile for particulate matter levels in the air, measured in micro-grams per cubic meter, was 22. Generally, particulate matter refers to liquid and solid particles suspended in the air; more specifically, PM 2.5 refers to atmospheric particulate matter with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometers. The percentile does seem low initially; however, one would expect this number to be much lower in a rural area, since more rural areas tend to have less levels of air pollution than urban areas.

Bradford County is also in the forty-eighth percentile for proximity to hazardous waste management facilities, which is, once again, a high percentile for a rural area. Perhaps this high count of Treatment Storage and Disposal Facilities (TSDF) is necessary to cope with the waste produced by hydraulic fracturing, such as fracking fluids. The increased number of these facilities, in simple statistical terms, increases the exposure of residents to the disposal and storage of hazardous wastes. The most revealing piece of environmental data is that Bradford County is in the eighty-second percentile for Wastewater Discharge Indicator. This number refers to the concentration of toxics in streams within five hundred meters divided by distance, in kilometers. The wastewater produced by fracking is laced with chemicals and radionuclides, and although it is initially pumped underground, it eventually flows out of the well as wastewater.

These demographic and environmental factors coalesce in a way that creates a narrative of hydraulic fracturing in Bradford County, PA. Based on the aforementioned demographic data, most of the residents of the county are undereducated;, this factor could imply that residents might not be fully aware of the environmental and subsequent health ramifications that the process of hydraulic fracturing can have. For example, a seemingly invisible element, such as high particulate matter, may not even register as a potential health concern related to fracking until something more tangible, such as toxic wastewater discharge, makes itself known first. Moreover, these individuals are mostly elderly, have lower incomes, and tend to rely on agricultural output for that income. In these cases, knowledge of these environmental ramifications could exist, but cannot be addressed, especially since these particularly vulnerable individuals might not have the requisite means to relocate, which would require selling their sole source of income, or to seek legal recourse. In a sense, their vulnerabilities are exacerbated.

Companies, then, such as Chesapeake Appalachia LLC, specifically target these individuals with the notion that wells be drilled into their properties. They are promised high amounts of money to lease their land. Based on that analyzed demographic data, there is no doubt that this initial offer would be enticing: a potential influx of much needed income could serve to fortify their small farms. However, they usually receive a much smaller amount (or are actually forced to pay the companies, as seen in the Image Analysis of “PA Royalty Ripoff). All the while, they face the health issues that come as a result of certain inevitabilities, such as breathing in air that contains such a high concentration of particulate matter, as well as dealing with violations of fracking policy that manifest themselves through hazardous waste leaks from waste management companies and wastewater discharges. Their health, as well as the health of any of the animals they may have on their farms, begin to deteriorate. Fully contaminated farms end up going for sale at a dramatically reduced price, allowing companies to purchase land cheaply to build even more wells.

Some examples of environmental inequality in the United States, as a whole, can stem from the opportunity of those in power to prey on a vulnerable population for monetary gain. Age and class are major demographic factors that are especially important in this consideration, as seen in Bradford County. Moreover, rural communities in particular as targeted in this sense, as many small farms across the United States face similar decisions and consequences today.

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

This video recounts the experiences between 2010 and 2012 of Sheila Russell, who, with her family, owns a farm in Bradford County, PA . Her story is one that is shared by many farmers in the county dealing with fracking and its subsequent environmental and economic ramifications. This video additionally provides a very brief overview of the process of fracking itself.