Farms to Cradle: Inequity in Preserving the Garden State’s Green Belt

by Donovan Kirkland

Site Description:

This project examines the inequities of farmland preservation and New Jersey. As defined by the state, “New Jersey’s farmlands are the foundation for a strong agricultural industry and a way of life for generations of farm families. Scenic landscapes of green, productive fields are an important part of what makes New Jersey a desirable place to live.” However, the state fails to address what populations actually reap the benefits of the preserved land. While preservation efforts are publicly funded state wide, benefits are often localized. Through the case study of several farms throughout the state, anti development NIMBYism, agritourism, and other local, or private interests have proven to play a significant role in the preservation efforts rather than regional planning, ecological, and food security incentives. This dynamic further highlights the fracture in environmental movements between “white” and “black” environmentalism; where the former is concerned with preserving the benefits of environment and the latter is consumed with the consequences of the environment.

Final Report:

“Bindon Farm Preserved in Bedminster Township”[1] is a 2018 blog post made by The Land Conservancy of New Jersey, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving land and natural resources. The article outlines the organization’s latest conquest: a 67 acre scenic hay farm in Somerset County. The land once belonged to the late Alice Lorillard, an avid conservationist, and pillar of the local equestrian community who wished to ensure her acres would remain a farm for years to come. While her wishes were carried out through the advocacy of The Land Conservancy and the county Agriculture Development Board, they were only made possible through New Jersey’s farmland preservation program: a $1.7 billion state run investment program whose objective is to “maintain the viability of agriculture” through purchasing individual farm properties and/or their future development rights to ensure continuous agricultural use[2]. Unfortunately, Alice’s farm’s viability and the legacy of her wishes were not the only impetus behind the land’s induction into the program. In fact, her acreage is a part of a local land use planning strategy that leverages the farmland preservation program to throttle development in exclusive neighborhoods. This misuse is indicative of a structural inequity where preservation and its benefits are made exclusive to wealthy suburbanites.

As it turns out, Alice’s land donation was a key acquisition for the region’s “growing farm belt”. Land Conservancy President, David Epstein, described the farm’s role in a larger strategy for land use planning: “The farm is important to the agricultural landscape of Bedminster Township as it lies in the swath of preserved land and farms, which now totals 480 acres with the addition of Bindon farm.” Mark Caliguire, liaison to the county’s agricultural development board describes the acquisition as an, “excellent purchase in that it builds on previously preserved easements.” Alice’s farm, along with the cluster of other preserved parcels in Bedminster’s farm belt are the result of a unique recipe of state funds, private lands, local interests, and grassroots advocacy. This particular intersection of parties, where there is also an intersection of priorities creates a strong foothold for nimbyist activism that remains one of the largest blights on an otherwise positively intentioned program. Through cultivating this preserved land belt, Bedminster is able to ward off any significant morphological change to their community and thus preserve its exclusive quality.

Although the preservation program is meant to protect New Jersey’s agricultural heritage and industry through barring development, it also can be abused by organizations like local agricultural development boards to form permanent green buffers around their communities. As the accumulated farmland is protected, buffers immunize these select communities from development, and insulate their value with the benefits of adjacency to open space, exclusive housing stock, access to farm fresh foods, and the economic boost from agritourism. This accumulation practice results in most preserved farm parcels ending up in the wealthy outer suburbs where land is plentiful, yet anti-development sentiments are popular to preserve the character of their communities. When the farmland preservation program is abused in this way, it creates a dynamic where many who pay into the billion dollar effort of preservation, do not have direct access to its benefits.

When examined through the lens of the racial history of land use planning in suburbia, the inequity infused into the preservation program becomes an environmental injustice issue where urban populations of color are excluded from benefiting from farmland adjacencies. The well documented process of redlining, and “white flight” have left a racial and economic divide between urban and suburban population’s demographics. This divide has left behind a legacy of financial and political divestment that leaves them underserved by industry and public services. The divide also extends to a toxic philosophy in environmentalist policy where urban areas are not viewed as places worth considering as a part of environmental programs. This leaves communities without access to local farm fresh produce or green and open spaces. Meanwhile, the very same underserved communities are actively contributing via state or local taxation to farm preservation efforts outside of their own communities and therefore out of their reach. While the preservation program makes no concessions for communities without land to offer, there is no objection to accepting tax contributions at the county and state level. As it is currently constructed, the farmland preservation program lacks the intersectionality to serve all of its contributing populations equally.

At the same time, it is important to realize that New Jersey’s farmland preservation effort is acting in the interest of our ecology in a larger existential debate around agricultural land use. According to the American Farmland Trust report, Farms Under Threat: The State of The States,[3] “the United States is home to 10 percent of the planet’s arable soils – the most of any country on Earth.” As populations grow and demand for food grows, maintaining our viable agricultural lands is of chief importance. However, an increase in population also means an increase in demand for housing and infrastructural development. Unfortunately, in many cases, these two demands are vying for the same land. According to the same American Farmland Trust report, “between 2001 and 2016, 11 million acres of farmland and ranchland were converted to urban and highly developed land use (4.1 million acres) or low-density residential land use (nearly 7 million acres).” This concern of creeping development impacting critical farmlands is especially topical in New Jersey. In the state there is an exceptional demand for housing and exceptional contributions to national agricultural production. For example, the garden state ranks #1 in property tax[4], #10 in cost to own a home[5], and is the most densely populated state in the United States of America[6]. Simultaneously, New Jersey is also one of the top ten national producers for about 11 different types of fruits and vegetables. Due to this tension, the Garden State has adopted one of the most progressive preservation plans in the nation[7]. It is undeniable that Farmland Preservation is an important task. Agricultural production is of paramount importance to our society as a whole. However, the solution presented must touch all populations to truly be effective.

While some critics are concerned with its morphological consequences and economic feasibility, my intention is to link the factors that contribute to injustice in specific communities in order to highlight the programs lack of intersectionality. In an article published in 2001 by New Jersey Future, a non-profit organization that promotes sensible growth redevelopment and infrastructure, “Rethinking Farmland Preservation in New Jersey”[8] criticizes morphological consequences and economic inadequacies of the program. New Jersey Future raises concerns about how the amount of financial resources available are not sufficient to save enough farmland in the coming decades. Additionally, the article mentions the inconsistent pattern of preserved easements resulting in opportunities for “intrusive residential development” among preserved areas. However valid, New Jersey Future’s criticisms only question the effectiveness of the program and does not address any potential for injustice or inequality.

On the other hand, in the 2003 article Dilemmas of environmental Planning in Post Urban New Jersey[9], author, Robert W. Lake of Rutgers University discusses New Jersey’s State Land Use Plan, a larger plan that includes all open space and environmental planning through the lens of the state’s period of post war racially charged urban exodus. His article rethinks the suburban versus urban divide in environmentalist policy. In most of New Jersey’s land use plan, development and urbanity is viewed as antithetical to environmentalism. Thus, the idea of preservation becomes expressly anti-urban and anti-development. His main assertion echoes a popular idiom: a house divided against itself cannot stand. He argues that in order to reach a true solution to the state’s land use issue, one cannot pit the urban and suburban sides of the proverbial house against each other as current land use policy suggests. In fact, land use policies must account for the urban environment and allow for responsible development in order to be truly sustainable and ecological. Lake also acknowledges how, as a result of urban exodus, that the urban-suburban rift in policy is also an implicitly a racial rift. My paper intends to build upon this by applying these criticisms to the farmland preservation program and discussing how specific communities are affected by this rift in environmentalist policy.

Lake’s idea of this fundamental divide between urban and suburban communities is the basis for the difference in accessibility to the farmland preservation program. In order to understand the depth of the rift, first, I will examine the social history and changes of the farmland preservation program as it runs parallel to the urban exodus, suburban housing crisis and resulting development boom characteristic of the post-war period throughout the United States. Drawing the connection between both timelines will help further contextualize farmland preservation’s role in upholding the divisive environmental policy and anti-development tool. Second, I will discuss the consequences of the program on suburban morphology and how they deepen the rift between suburban and urban communities. Afterwards, I will take a closer look at two different urban communities, both struggling against food insecurity, Newark New Jersey and Salem New Jersey, to highlight their relationships to farmland preservation.

The Changing History of Farmland Preservation

In order to understand the intent of the farmland preservation program, it is important to understand how it’s changed over time. While the goal to preserve agricultural lands remains the same, its means of doing have transitioned from a mostly pro-agriculture policy to a staunchly anti-development policy. This transition is where Lake’s argument applies. In order to reach a unified environmentalist solution, development must be included in the plan and not painted as an inherently anti-environmental act. The two major landmarks of policy change as they relate to preservation of agricultural lands in New Jersey were the Farmland Assessment Act of 1964 and the Agriculture Retention and Development Act of 1981. The former was a step in the right direction, enacting an incentive program for farmers in the hopes of retaining more agricultural land, while the latter was directly aimed at slowing development altogether.

Often referred to as the first step in farmland preservation, the Farmland Assessment Act of 1964[10] incentivized qualifying farmers with favorable tax assessments of their properties. The act was conceived as a pro-farm policy, intentionally focused on boosting farmland retention rather than slowing development. Farmland assessment works by permitting, “farmland and woodland acres that are actively devoted to an agricultural or horticultural use to be assessed at their productivity value.” This measure essentially gave owners a discount on property taxes as long as they were continuously used as farms. Although the act was intended to slow development, it did not paint development as antithetical to preservation. The program simply provided an incentive to continue farming in the face of pressures to develop.

However, The Farmland Assessment Act wasn’t enough to hold back development in the tail end of the post war housing boom. The program arrived too late. Most of the GI bills from World War Two had already been cashed and the suburban tract housing model had already proven to be a very successful catch basin for the populations flowing out of rapidly integrating cities. The need for suburban housing far exceeded the supply and as a result many farmers opted to cash in on their lands and sell to hungry developers despite the state’s incentives. For reference, New Jersey’s very own Levittown[11], one of the United States’ most infamous archetypal suburban developments, had been complete for over a decade by the time farmland assessment was signed into law.

Although suburban development was seen as a threat to farms, the rapid suburbanization of the United States housing was also a rapid suburbanization of the United States mindset. The mid 60s, around the same time The Farmland Assessment Act was signed into law, also marked several other watershed moments in the environmental movement[12] including the publishing of Rachel Carson’s Silent spring and the establishment of the Clean Air and Clean Water acts. Ironically, the enemy of farmland preservation may have been its saving grace. As more and more Americans adopted a suburban lifestyle, they began to cherish the qualities of the countryside in contrast to the densely populated and polluted environments that characterized the cities of that time. Through this shift in mindset, cities were painted as the antithesis of this new found environmentalism. As a result, policy followed suit and took a more aggressive, defensive stance against development out of fear that the clean, green, and open suburbs would succumb to the same fate as the cities if left unchecked.

In 1981, New Jersey passed the Agricultural Retention and Development Act[13], which took a more aggressive, anti-development approach to preservation. This act established the modern method of farmland preservation that we see in practice today in which the state purchases farm development rights for extended, and often indefinite periods of time in order continuous agricultural use. Individual farms of a minimum size that can demonstrate compliance with a state guideline for soil quality and production can qualify to opt-in and apply to exchange their future development rights for a sum of state funds. This exchange is more anti-development than it is pro-farm because landowner’s must forfeit their equity to receive benefit. The marquee difference between the 1964 assessment act and the 1981 retention act is the permanence and invasiveness of the latter solution. Unlike the 1964 act, landowners were required to enter a transaction with the state rather than simply qualifying for a benefit. The state markets this transaction as an opportunity for farmers to free capital to expand their business, or take on projects[14]. In a sense, these funds are the state’s appraisal of the landowner’s existing equity and therefore does not add net value to the transaction. At the end of the day, the state gets what it wants: lands permanently dedicated to agriculture, promised to remain undeveloped. However, the act seems to have little to offer to the actual businesses that occupy them.

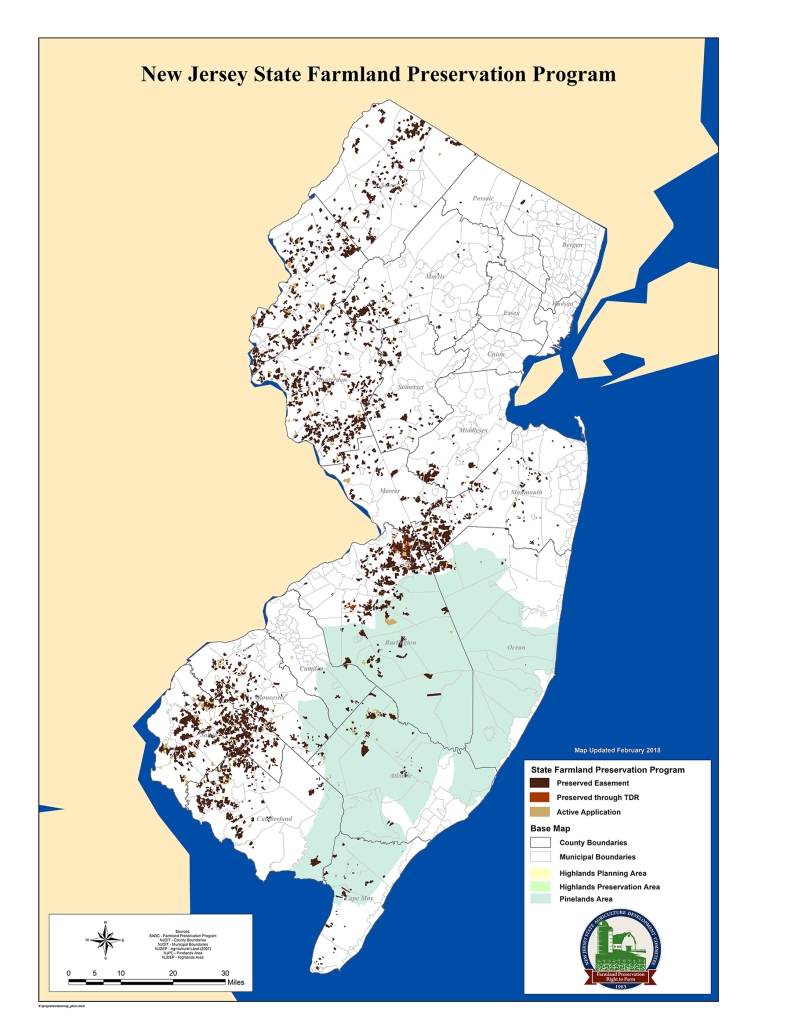

While the jury is still out on the act’s overall effectiveness, it has proven to be very prolific. To date, the program has saved 2,500 parcels amounting to 238,000 acres[15] and has had a significant effect on the morphology of the state. The map below is a depiction of all of the preserved farms, and active applications in New Jersey overlaid on municipal and county boundaries as of 2018. Each brown, tan, or orange spot represents one parcel of land that is currently, or proposed to serve an agricultural use for the foreseeable future. One of the most striking qualities of this map is the distribution of the preserved parcels throughout the state. Aside from a few outliers, the parcels are biased to the western half of the state, with a regular spotty distribution in the north, and two distinct, dense clusters in the south. Noticeably, preservation entirely avoids Essex County, home the largest black population in the state[16] and the largest city in the state. This pattern is the end result of a problematic morphology made possible by the processes of the program itself and reinforced by its participants.

In order to understand the spotty distribution of preserved lands throughout the state, we must first understand the process that an individual parcel must undergo in order to be considered for preservation through government purchase of future development rights. Throughout the process there are many factors that can determine the eligibility for preservation. Unfortunately, the main result of the many variables and moving parts of the preservation process is inconsistency. Firstly, the land must meet a minimum criteria set forth by the State Agricultural Development Committee (SADC) including, size, adjacencies and zoning determined by county, sales, soil viability, and agricultural sales. This regulation alone places preservation out of reach of the most populated areas of the state. Once lands have met the minimum criteria, approvals are granted by the SADC and land undergoes an appraisal. Finally, if terms are agreed to, then purchases are finalized. It is also important to note that landowners must opt-in to the preservation program individually in order to be considered. Often, local boards and organizations lobby for preservation of particular parcels in their area. In short, some parcels are preserved, and some aren’t. Additionally, with no overarching plan to organize the manner in which preserved lands are distributed, parcels end up relegated to the far flung suburbs, and often sharing adjacencies with unpreserved land that is still vulnerable to sale and development.

Biases of Farmland Preservation

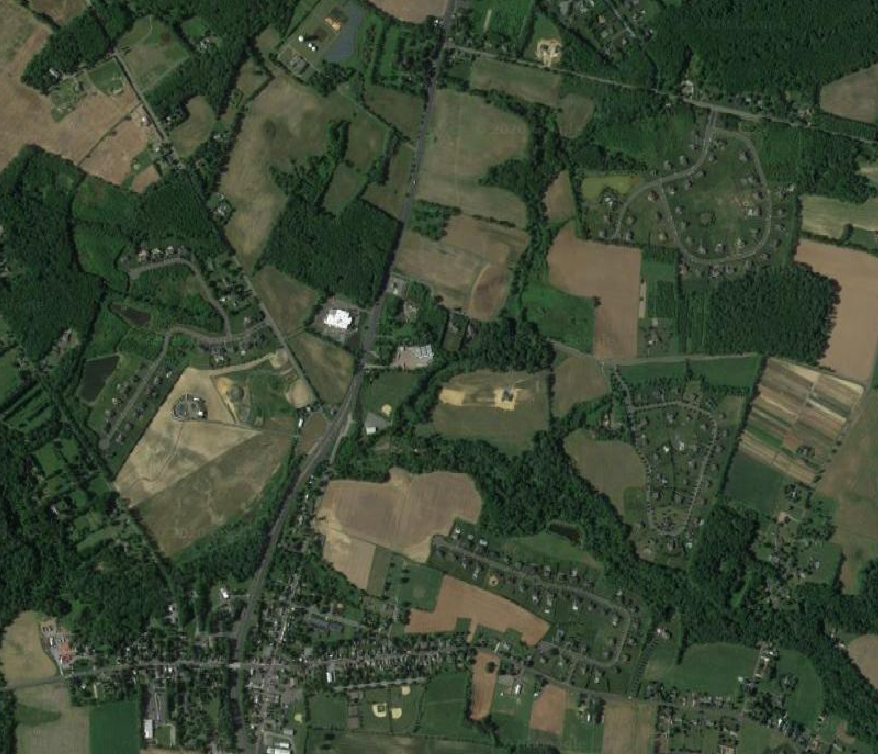

The most concerning part about sporadic distribution of preserved lands is the potential for the sprawling exurban development islands they create. These islands are neither not productive for contiguous agricultural use, or a sustainable solution for development. Published in 2001, the New Jersey Future Report: Rethinking Farmland in New Jersey warns us of the “checkerboard preservation pattern” arising from preserved land. It states, “Farm properties have been preserved in a checkerboard pattern that permits – and often encourages – intrusive residential subdivision.” For example, consider the satellite image below from Columbus New Jersey, located in the heart of the Burlington county cluster of preserved farms. The alternating pattern of agricultural land, and developed housing tracts creates a problematic checkerboard style pattern where housing developments are isolated on their own islands.

The resulting “intrusive residential subdivisions” as they are described in the New Jersey Future report, are used to fill the voids left over by preserved lands and create an unsustainable exurban condition for residential development. Since these void lands are surrounded by preserved property, it is nearly impossible to connect them to public transportation infrastructure, supporting industrial, or commercial development, and other complementary types of development. This isolation creates a breeding ground for large single family homes, or commuter style developments. Without the support of transportation and local infrastructure these developments are largely exclusive, resulting in a predisposition to wealthy residents, and therefore upholding the dynamics of the urban-suburban divide. Additionally, these developments are highly defensible against any significant morphological change because the lands that they are protected are legally required to remain agricultural.

A short survey of the area depicted in Columbus above reveals its character. Each loose curl of meandering cul de sac is dotted with palatial McMansions[17]. This is no coincidence. The open space preserved with public funds supposedly for the good of the whole is an asset to these homeowners. Their real estate listings cite their acreage and amenities adjacent to the square footage and room counts themselves[18]. Recall Alice’s farm and the actors involved in its preservation and addition to Bedminster’s green belt. The process of preserving these islands of development is active and intentional, but only made possible due to the bias of the preservation policy. When farmland is restricted in such a way that only areas like these can reap the benefits, the program is bound to be imbalanced and further reinforces the socioeconomic disparity in environmental movements.

Aside from benefits to property value, those adjacent to a surplus of farmland unfairly benefit from the newly emerging agritourism industry. Agritourism is colloquially defined as the business of inviting the public onto farms for recreational enjoyment and or education. This includes but is not limited to hunting, fishing, bird watching, self-picking produce and horticulture, seasonal events, and tours. These activities disproportionately benefit those in the immediate area of farmland or privileged with expendable time and income to travel and partake in these offerings. While the intentions and activities are wholesome and well intentioned, the use of these funds for private profit and localized amenities does not promote a unified environmentalism.

As it stands, a significant portion of farm income is from agritourism. The Rutgers University report: The Economic Contributions of Agritourism in New Jersey[19] analyzes a large sample size of farms and how their income is related to agritourism. As the report shows agritourism is a large, and growing market for New Jersey farmers. The University conducted a large study consisting of surveying and interviewing 1,500 random farms of varying sizes and locations in New Jersey. The farms were compiled from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service database and asked about their relationship to the Agritoursim business. The survey found that approximately 1:5 farms offer some sort of Agritourism, roughly 2,200 farms total throughout the state. Of those that support agritourism activity the 70% of revenue came from sales, while the remaining 30% was a mixture of educational, entertainment, recreational, and accommodation activities amounting to a total of 57 million dollars in Agritourism revenue state wide.

The large growing market for Agritourism is concerning because it adds incentives for farmland preservation beyond its original mission of supporting a strong agricultural industry. Preserving lands to create an agritourism site rather than making a viable business based on crop production and land cultivation prioritizes the local benefits of open space and additional revenue from out of town tourism without the onus of production that reaches beyond the farm’s immediate area.

Preserved farms have a responsibility to those that fund them, and often those responsibilities go unfulfilled in surprisingly close adjacencies. While it may be a consequence of New Jersey’s tight knit municipalities, the lack of response in urban and minority communities exist in stark contrast to the symbiotic relationship enjoyed in the exurban, rural, and suburban parts of the state.

Case Study #1: Salem City, NJ

Inequity between preservation efforts and minority populations is especially palpable in Salem City New Jersey, a predominantly black municipality located near the southwestern cluster of preserved farms in the state. Although the city is in relatively close proximity to an abundance of preserved farmland, according to a 2018 special report by NJ Spotlight News[20], the city has been struggling with food insecurity. At the time, it was reported that Salem City, home to approximately 5,000 residents, had zero grocery stores within its city limits and was officially classified as a food desert: a place where residents do not live within one mile of a source of fresh produce. For groceries, residents relied on a mixture of local convenience oriented stores for staples like frozen meats and vegetables. Ironically, according to the New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program Summary (chart below), Salem County, Salem City’s farmland preservation contribution beneficiary, has the most preserved farmland in the state totaling upwards of 40,000 acres which accounts for 17% of all preserved farmland in New Jersey. However, according to the mayor, since most residents in Salem City do not have access to reliable transportation the farms are out of reach. However, it would be unfair to depict the residents of Salem as helpless. In order to make up the difference, the city has partnered with non-profit food banks like the Food Bank of South Jersey that distributes fresh food to residents and provides nutritional education and cooking classes. While Salem’s situation may not be the direct result of the failures of the farmland preservation program, it highlights the need for intervention in a community that contributes to the program, and the programs inability to do so. After all, if preserved farms cannot provide their own beneficiaries with food, what’s the point of preserving anything at all? Wouldn’t Salem’s energy and money be better spent in continuing their internal fight against food insecurity? Without the ability to consider populations of varying socioeconomic status, preservation cannot be intersectional.

Case Study #2: Newark, NJ

Further north, in Newark, New Jersey’s largest city, historically also struggled with food insecurity. In an act of self-reliance, the city, similar to Salem also took its fate into its own hands and created a network of community gardens to address the issue. Throughout the years, Newark was infamously devoid of supermarkets and was a poster child for the hallmark urban divestment of the postwar United States. In order to address this issue, activists from the Greater Newark Conservancy[21], an environmental stewardship to improve the quality of life in New Jersey’s urban communities created a clever network of community gardens. In the program residents grow fruits and vegetables in designated lots scattered throughout the city. Then, a portion of the harvest is shared amongst those who put in sweat equity to cultivate the land and the rest is sold at reasonable prices to other community members. These community gardens and associated farm shares, similar to South Jersey’s food banks, are a hub for healthy food and nutritional information for residents with low access to fresh produce. Essex County, where Newark is located, does not currently have any preserved farmland however the municipality still contributes at the state level. Unfortunately, the program is not equipped to have a direct effect on the urban environment or dense surrounding suburbs. However, agriculture is still an incredibly important solution in their community’s food landscape. If preservation’s mission is to protect the viability of agriculture, why are there no provisions for agriculture in urban environments? Without the ability to consider urban environments as part of an ecological solution, the farmland preservation program cannot be intersectional.

Conclusion

In the grand scheme of things, Alice’s beautiful 67-acre hay farm is not going to help fill anyone’s stomach because people don’t eat hay. This unfortunate truth is indicative of a larger issue in environmental movements in general. Often, movements are fractured because the environment we see and are privileged to experience is the only environment we can consider. For those in Bedminster, preserving ensures their community has space for horses to roam is what environmentalism looks like for them. For the Conservancy in Newark, or the food bank in Salem environmentalism is simply a nutritious diet. However, this fractured environmentalism is the basis for injustice when enacted into policy.

The inability of farmland preservation to serve all populations equally is what is at the heart of its inherent injustice. Without the intersectional ability to intervene and provide equal care to each contributing population in the state, the results, however positive in one area will always be unjust and unequal in another. The programs proclivity to latch on to wealthy suburban communities is a culmination of its legal construction and the stigmatic attitude towards development carried over from the social history of white flight and the ensuing urban divestment. By making an enemy of development and urbanism, the policy also made an enemy of diversity and access to farmland’s possible benefits, even for its own beneficiaries. These power structures are upheld by nymbists who leverage preservation to protect their insular communities against progressive change. In the end, minorities and urban populations are left on the outside looking in.

When thinking about how to improve the farmland preservation program, Robert Lake’s call for a unified approach comes to mind. The dichotomy of the built environment and the natural environment must be rejoined into one conversation where one side accounts for the other. Development and nature and agriculture and housing must all coexist in the same ecological system in order to create a sustainable future. In order to work at an all-encompassing level, farmland preservation must consider both sides of each dichotomy, and offer a planning solution for responsible inclusive development and agriculture to coexist, and include urban agriculture, through implementation or distribution to reach struggling communities who need a return on their preservation investment.

Keywords: Food, Class, Race, Soil, Business

[1] “Bindon Farm Preserved in Bedminster Township.” TLCNJ. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://tlc-nj.org/bindon-farm-preserved-bedminster-township/.

[2] “New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program: Overview.” New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program | Overview. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/sadc/farmpreserve/.

[3] Freedgood, Julia, Mitch Hunter, Jennifer Dempsey, and Anne Sorensen. “Farms Under Threat: The State of the States.” Washington DC: American Farmland Trust, 2020.

[4] Cammenga, Janelle. “How High Are Property Taxes in Your State?” Tax Foundation. Tax Foundation, August 31, 2020. https://taxfoundation.org/how-high-are-property-taxes-in-your-state-2020/.

[5] Hoffower, Hillary. “The Most Expensive and Affordable States to Buy a House, Ranked.” Business Insider. Business Insider, July 5, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/cost-to-buy-a-house-in-every-state-ranked-2018-8.

[6] U.S. States Populations, Land Area, and Population Density. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.states101.com/populations.

[7] “Department of Agriculture: About NJDA.” Department of Agriculture | About NJDA. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/about/overview.html.

[8] “Rethinking Farmland Preservation.” njfuture.org. New Jersey Future, 2001. https://www.njfuture.org/research-reports/rethinking-farmland-preservation-in-new-jersey/.

[9] Lake, Robert W. “Dilemmas of Environmental Planning in Post-Urban New Jersey*.” Social Science Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2003): 1002–17. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0038-4941.2003.08404013.x.

[10] “Department of Agriculture: Farmland Assessment.” Department of Agriculture | Farmland Assessment. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/home/farmers/farmlandassessment.html.

[11] “Township History.” Willingboro Township. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.willingboronj.gov/about-us/township-history.

[12] “The Modern Environmental Movement.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/earth-days-modern-environmental-movement/.

[13] New Jersey Agriculture Development Committee, The Agriculture Retention and Development Act § (1981).

[14] “New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program: Overview.” New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program | Overview. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/sadc/farmpreserve/.

[15] State Agriculture Development Comittee, New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program Summary of Preserved Farmland Through 07/31/2020 § (n.d.).

[16] “Cities with the Highest Percentage of Blacks (African Americans) in New Jersey.” Cities with the Highest Percentage of Blacks (African Americans) in New Jersey | Zip Atlas. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://zipatlas.com/us/nj/city-comparison/percentage-black-population.htm.

[17] McMansion Hell. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://mcmansionhell.com/.

[18] “16 Legends Ln, Columbus, NJ 08022: MLS #NJBL377136.” Zillow. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/16-Legends-Ln-Columbus-NJ-08022/87960042_zpid/.

[19] Schilling, Brian, Kevin Sullivan, Stephen Komar, and Lucas Marxen. “The Economic Contributions of Agritourism in New Jersey,” 2011. https://sustainable-farming.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/The-Economic-Contributions-of-Agritourism-in-New-Jersey-e333.pdf.

[20] Vannozzi, Briana. “Jersey Is the Garden State, so Why Are There Food Deserts?: Video.” NJ Spotlight News, 2018. https://www.njspotlight.com/news/video/jersey-is-the-garden-state-so-why-are-there-food-deserts/.

[21] Greater Newark Conservancy : Home. Accessed December 17, 2020. https://www.citybloom.org/.

Primary Sources:

Farmland Assessment Overview, New Jersey Department of Agriculture, 2015, pp. 1–20.

The farmland assessment overview provides insight on the criterion for land to be preserved. Also, the overview provides access to the legalities and top down governmental actions and motives to preserve farmland and open space.

“Malon Farm Preserved!” TLCNJ, The Land Conservancy of New Jersey, 21 Feb. 2017, tlc-nj.org/malon-farm-preserved/.

The narrative of the Malon Farm preservation story details the grass roots approach taken to farmland preservation. It also touches on the ideas of farm preservation as a preservation of culture, amenity space, and beauty.

“New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program Permanently Preserved Farmland by County.” State of New Jersey Department of Agriculture State Agriculture Development Comittee, 25 Oct. 2019.

The New Jersey Farmland Preservation Program published a comprehensive list of permanently preserved farms in the state. This data provides insight to the diversity of properties, acquisition methods, locations, and other granular information about potential case studies for analysis.

New Jersey Future, 2001, Rethinking Farmland Preservation in New Jersey, http://www.njfuture.org/research-reports/rethinking-farmland-preservation-in-new-jersey/. Accessed 14 Oct. 2020.

The Rethinking Farmland Preservation report provides insight to a grass roots organizations assessment of the feasibility and effectiveness of top down farmland preservation initiatives. Grass roots criticism of a top down movement provides an alternative viewpoint on the issue of farmland preservation strategy and solutions. This report also provides further insight to the effects of farmland preservation on the urban morphology of exurban and rural New Jersey. Preserved farmland can act as a function of anti-development “nimbyism” further catalyzing exurban conditions and irresponsible sprawl.

Schilling, Brian J, et al. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey, 2011, pp. 1–5, The Economic Contributions of Agritourism in New Jersey.

This report breaks down the share of profit that comes from agritourism vs. crops in New Jersey. Usage of preserved farms as agritourism sites are proof of farms being used as amenity space that only benefits their local populations rather than makes use of the productive lands for a wider range of people.

“Warren County Permanently Preserves Its 300th Farm.” Insider NJ, InsiderNJ, 22 July 2020, http://www.insidernj.com/press-release/warren-county-permanently-preserves-300th-farm/.

This article provides a perspective of New Jersey farmland preservation initiatives relative to country and global agricultural and ecological movements. New Jersey plays a significant role in farmland preservation efforts at a larger scale which provides context to the scale of preservation in the state.

Secondary Sources:

Mock, Brentin. “Are There Two Different Versions of Environmentalism, One ‘White,” One ‘Black’?” Grist, 31 July 2014, grist.org/climate-energy/are-there-two-different-versions-of-environmentalism-one-white-one-black/.

This article provides insight to the two sides of the environmental movement and the exclusion of minorities and other disenfranchised communities. With regard to farmland preservation in New Jersey, without all voices, preservation strategies are bound to be insensitive to the needs of all people in the state.

Perelman, Michael. Farming for Profit in a Hungry World: Capital and the Crisis in Agriculture. 1979.

Farming for Profit in a Hungry World sheds light on the contradiction of farming and the economic motivators behind agriculture. The author is explores the theme of the relationship between agricultural practice and its contributions to food inequities. A similar contradictory relationship exists between New Jersey food deserts and state preserved farms.

Perelman, Michael. Farming for Profit in a Hungry World: Capital and the Crisis in Agriculture. 1979.

Farming for Profit in a Hungry World sheds light on the contradiction of farming and the economic motivators behind agriculture. The author is explores the theme of the relationship between agricultural practice and its contributions to food inequities. A similar contradictory relationship exists between New Jersey food deserts and state preserved farms.

Schmidt, Hubert Glasgow. New Jersey Agriculture: a Three-Hundred-Year History. Rutgers U Pr., 1973.

New Jersey Agriculture provides a concise resource of agricultural history in the state of New Jersey. Referencing this history will provide further perspective for the cultural significance of farming in New Jersey and clarify the qualitative ambitions of farmland preservation initiatives.

Vannozzi, Briana. “Jersey Is the Garden State, so Why Are There Food Deserts?: Video.” NJ Spotlight News, 19 Sept. 2018, http://www.njspotlight.com/news/video/jersey-is-the-garden-state-so-why-are-there-food-deserts/.

This article further highlights the contradictory nature between the prevalence of farmland and the food inequities throughout the state. This contradiction among others is the crux of the injustice surrounding farmland preservation efforts.

Lake, Robert W. “Dilemmas of Environmental Planning in Post-Urban New Jersey.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 84, no. 4, 2003, pp. 1002–1017. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42955918. Accessed 15 Oct. 2020 (Links to an external site.).

Dilemmas of Environmental Planning outlines the urban morphological and ecological concerns of relegating open space preservation to strictly suburban contexts. By characterizing farmland preservation as a movement that is only for suburban and rural areas, strategies are ignorant of urban populations’ needs. This further highlights the disparity between locations and ultimately populations of people and their access to the perceived ecological and qualitative benefits of preservation.

Image Analysis:

One of the criticisms of the farmland preservation program is its effect on the morphology of development in the state. The map above is a depiction of all of the preserved farms, and active applications in New Jersey overlaid on municipal and county boundaries as current as 2018. Each brown, tan, or orange spot represents one parcel of land that is currently, or proposed to serve an agricultural use for the foreseeable future. One of the most striking qualities of this map is the distribution of the preserved parcels throughout the state. Aside from a few outliers, the parcels are biased to the western half of the state, with a regular spotty distribution in the north, and two distinct, dense clusters in the south. This pattern is the end result of a problematic morphology fuelled by the processes of the program itself.

In order to understand the spotty distribution of preserved lands throughout the state, we must first understand the process that a parcel must undergo in order to be considered for preservation through government purchase of future development rights. Throughout the process there are many factors that can determine the eligibility for preservation. Firstly, the land must meet a minimum criteria set forth by the State Agricultural Development Committee (SADC) including, size, adjacencies and zoning determined by county, sales, soil viability, and agricultural sales. Once lands have met the minimum criteria, approvals are granted by the SADC and land undergoes an appraisal. Finally, if terms are agreed to, then purchases are finalized. It is also important to note that land owners must opt-in to the preservation program individually in order to be considered. The main result of the many variables and moving parts of the preservation process is inconsistency. In short, some parcels are preserved, and some aren’t. With no overarching organization preserved lands are distributed sporadically sharing adjacencies with unpreserved land that is still vulnerable to sale and development.

The most concerning part about sporadic distribution of preserved lands is the potential for exurban development islands they create. Published in 2001, the New Jersey Future Report: Rethinking Farmland in New Jersey warns us of the “checkerboard preservation pattern” arising from preserved land. It states, “farm properties have been preserved in a checkerboard pattern that permits – and often encourages – intrusive residential subdivision.” For example, consider four neighboring farm parcels in a district that is newly eligible for state level preservation: parcels A, B, C & D. The owner of parcel A opts in to the preservation program and is approved. The owner of parcel B does not opt in and sells their property to a developer. The owner of parcel C, similar to A opts in and is approved. Lastly, the owner of parcel D opts in and is rejected due to not meeting the sales criteria and is forced to sell their property to avoid bankruptcy. The alternating pattern of preserved, and developed properties creates a checker board of voids available for development surrounded by parcels that are bound to be farms indefinitely.

The resulting “intrusive residential subdivisions” described in the New Jersey Future report, used to fill the voids left over by preserved lands create an unsustainable exurban condition for residential development. Since these void lands are surrounded by preserved property, it is nearly impossible to connect them to public transportation infrastructure, supporting industrial, or commercial development, and other complementary types of development. This isolation creates a breeding ground for large single family homes, or commuter style developments. Without the support of transportation and local infrastructure these developments are largely exclusive, resulting in a predisposition to residents of high socioeconomic status based on race and class. There is a long and well documented history of inequity in suburban development, and these exurban developments continue to perpetuate that history.

Data Analysis:

The state preservation department defines New Jersey’s farmlands as the “foundation of a strong agricultural industry”. The description goes on to cite “productive fields” and “scenic landscapes of green” as driving factors for what makes New Jersey a desirable place to live. The public investment farmland preservation cannot be sustained or justified if farms are not profitable or bountiful as the state promises. However, profit and bounty are not always distributed equally. Not every tax paying contributing New Jerseyan is able to reap the benefits of how many farms make their money or distribute their bounty.

Many farms have shifted to Agritourism to drive revenue and garner support for farmer’s initiatives. Agritourism is colloquially defined as the business of inviting the public onto farms for recreational enjoyment and or education. This includes but is not limited to hunting, fishing, bird watching, self-picking produce and horticulture, seasonal events, and tours. These activities disproportionately benefit those in the immediate area of farmland or privileged with expendable time and income to travel and partake in these offerings. While the intentions and activities are wholesome and well intentioned, the use of these funds for private profit and localized amenities is not appropriate.

As it stands, a significant portion of farm income is from Agitourism. The Rutgers University report: The Economic Contributions of Agritourism in New Jersey analyzes a large sample size of farms and how their income is related to agritourism. As the report shows Agritourism is a large, and growing market for New Jersey farmers. The University conducted a large study consisting of surveying and interviewing 1,500 random farms of varying sizes and locations in New Jersey. The farms were compiled from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service database and asked about their relationship to the Agritoursim business. The survey found that approximately 1:5 farms offer some sort of Agritourism, roughly 2,200 farms total throughout the state. Of those that support agritourism activity the 70% of revenue came from sales, while the remaining 30% was a mixture of educational, entertainment, recreational, and accommodation activities amounting to a total of 57 million dollars in Agritourism revenue state wide.

The large growing market for Agritourism is concerning because it adds incentives for farmland preservation beyond its original mission of supporting a strong agricultural industry. Preserving lands to create an agritourism site rather than making a viable business based on crop production and land cultivation prioritizes the local benefits of open space and additional revenue from out of town tourism without the onus of production that reaches beyond the farm’s immediate area. Preservation that ends in agritourism is little more than an extension of nimbyism more concerned with maintaining the character of the state rather than its agricultural industry.