Igniting the SPARK: Portuguese Ironbound and the struggle for Environmental Justice in

Newark, N.J., 1960s-1990s

by Ethan Jardim

Site Description:

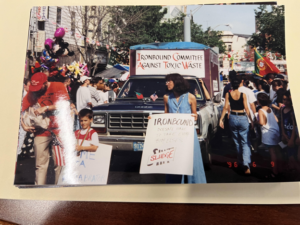

Riverbank Park Protests, Newark Public Library Internet Archive

In 1995, the Newark city government proposed a plan to construct a baseball stadium on Riverbank Park, located on Market and Van Buren Streets. The ballpark was intended to be for a minor league team managed by former Yankees player Rick Cerone. The majority of Ironbound’s residents, among them leaders of the Ironbound Community Corporation protested the construction of the stadium out of concerns of leading to issues of parking and traffic, as well as the lack of green and recreational space. The park was also closed during this time due to the soil being polluted from the nearby incinerator and sludge spill incidents. The ICC and other community groups in the Ironbound organized to fight the construction by establishing the Save Riverbank Park Coalition (SPARK). As the majority population of the Ironbound neighborhood, Portuguese American residents, among them organizers Irene DeOliveira, Anna De Costa, and former Newark city councilman Augusto Amador were essential actors in SPARK, the ICC, and the Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste. They helped spread awareness of the construction’s issues to the public through the trilingual(written in English, Spanish, and Portuguese) Ironbound Voices and the Portuguese-language Luso Americano newspapers. They also collaborated with ICC and SPARK leaders by holding referendums and petitions at Portuguese-run institutions such as the Portuguese Sports Club, Club Azores, and the former Iberia Restaurant, and Our Lady of Fatima on Ferry and Wilson Streets. The annual Portugal Day parade that is held on Ferry Street saw protests by SPARK through signs written in English and Portuguese. I believe that the fight to save Riverbank Park is important for my research and advancing scholarship on Environmental Justice, as it touches on urban development issues. Riverbank Park is considered an important recreational space for the Ironbound community. During the controversy over the ballpark’s construction, the park was officialized as a historic site by the Newark Landmarks and Historic Preservation Committee. Today, SPARK still manages recreational programs in Riverbank Park, strengthening the community. Riverbank Park is part of the Ironbound’s identity, and their success in saving it from demolition proves it. In discussing Environmental Justice history in the Ironbound, past scholars such as Matthew Immergut and Laurel Kearns wrote about how former immigrants who lived in Ironbound before the 1960s were more attentive of these issues than the Portuguese and Brazilians who replaced them. However, based on what I have learned through analyzing Ironbound Voices, Lusophone residents were very outspoken about Environmental issues. At what point did that change? Did most of the Portuguese community support Environmental movements?

Introduction

In the summer of 1996, both city residents and visitors gathered in Newark’s vibrant Ironbound neighborhood for the annual Portugal Day parade. Hundreds of people from different walks of life gathered on Ferry Street, the heart of the Ironbound, and joined in on the fun. There was everything from Portuguese food, music, and dance, costumes, and floats. People cheered from the sidelines as Ferry Street was filled with dancers, musicians, and busts of Catholic saints, kings, and the Virgin Mary. However, one wave of marchers stood out from the others. These folks were not dressed in traditional Portuguese clothing or were playing flutes or cymbals. Instead, they were dressed in casual summer apparel; t-shirts, shorts, baseball caps, etc. Ahead of them were three people carrying a banner that read “SPARK- Save Riverbank Park Coalition”. They were familiar faces, but what were they doing? Who was SPARK?

Portugal Day is an event that takes place every summer between June 8-10 and is celebrated by Portuguese communities both in Portugal and around the world. Portuguese immigrants carried on the tradition when emigrating to the US to celebrate and preserve their culture. The New Jersey Portugal Day parades were first started in 1979, with the largest in the Ironbound.

The Ironbound neighborhood of Newark has been known as a diverse immigrant community from various backgrounds, especially Portuguese. Aside from entertainment and cultural celebrations, the parade was historically used as a space for demonstrations by activists. However, these protests were done by a new group called the Save the Riverbank Park Coalition(SPARK). SPARK members were made up residents from the Ironbound as well as members of the ICC. The protest of the 1996 Portugal Day parade was organized against the Newark City Government, who planned to renovate Riverbank Park, located between Market and Van Buren Streets. News of the Newark Bears minor league baseball team new ballpark being constructed in Riverbank Park in late 1995 raised several concerns amongst folks in the Ironbound. Residents and local organizations feared that the construction would lead to an increase in traffic and pollution, and a decrease of green space in the neighborhood.

The Ironbound neighborhood is well-known as a thriving commercial district in Newark, even during urban decline in the 1960s. However, throughout its history the Ironbound has struggled with issues of waste and noise pollution as well as over-crowdedness caused by redevelopment projects and factories. These issues have had long-term negative consequences on the neighborhood’s diverse immigrant population, a majority of which a the time were Portuguese.

While environmental justice activism in Newark’s Ironbound was led by of a diverse mix of leaders and members, much of their success can be attributed to contributions from the prominent Portuguese American community. Since their settlement in the early 20th century, Portuguese Americans have contributed to the cultural scene in Newark through their churches, the Luso Americano Newspaper, and the Portuguese Sports Club located on Prospect Street. Through analysis of these socio-cultural spaces, institutions, and politicians, I argue that these factors were essential in driving the fight for environmental justice activism in the Ironbound.

While there has been much scholarship on Portuguese American communities in Northern New Jersey, most have focused on cultural aspects rather than their social or political achievements. Scholars have failed to acknowledge the roles that Portuguese Americans, particularly in the Ironbound, played in environmental justice activism against issues affecting their neighborhood. In “When Nature is Rats and Roaches,” environmental scholars Matthew B. Immergut and Laurel Kearns discuss the complicated history of religious institution’s involvement in environmental activism. They argue that in the case of the Ironbound, churches and clergymen, while initially supporters of community activist groups like the ICC in the early 90’s, did not engage with solving environmental problems until the early 2000s. Immergut and Kearns also point out that a lack of engagement from the Ironbound’s immigrant population; the Portuguese and Brazilians prioritized work, employment, and family’s needs over their surrounding environment.

Similarly, anthropologist and Rutgers-Newark professor Kimberly Da Costa Holton in her chapters in Community, Culture, and the Makings of Identity examines Portuguese American relations to their environment. In these chapters, her focus centers around the establishment of cultural spaces and products such as the Portuguese Sports Club, the Luso Americano Newspaper, and the popularization of Portuguese art, food, and dance in Newark. However, she does not go further in connecting cultural spaces to the social and political factors that occurred in Newark and the Ironbound throughout the 20th century.

In this essay however, I add to this scholarship by connecting Portuguese cultural spaces and institutions to environmental Justice activism in the Ironbound, thereby proving that Portuguese Americans were involved in environmental equity issues. I further argue through examination of vital Portuguese American spaces; namely churches, language-media, and sports clubs and leagues that Portuguese traditions and culture shaped and drove activism against environmental issues of pollution and redevelopment in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood. Portuguese American’s role in directing the Ironbound community’s environmental campaigns was tied to their rise in Newark politics through the formation of the Portuguese American Congress (PAC) and election of their own as city officials.

This paper will unfold in four parts. The first section of this paper will summarize the history of Portuguese settlement in Newark in the early 20th century as well as the establishments of key Portuguese institutions that later played a role in upholding environmental equity in the Ironbound between the 1980s to 1990s. The second section will focus on individual involvement of Portuguese residents in the ICC’s campaign against noise pollution from the Newark and JFK airports between the late 1970s to 1980. This section will explore how before Portuguese developed their own political platform, they first became active in environmental issues simply through residents joining the ICC’s demonstrations.

The third section will examine the role of that Portuguese Catholic parishes like Our Lady of Fatima as meeting grounds and the roles of Portuguese language publishers (Ironbound Voices and Luso Americano) in channeling news and promoting activism against the proposed incinerator from the At Sea company. This section will show the beginning of the shift from individual to institutional action from the Portuguese community and the rise of Portuguese in city politics. Finally, I will show in the fourth section Portuguese politicians and their commitment to community-based organizing through their collaboration with SPARK and the ICC in the Fight to Save Riverbank Park between 1996-1998.

The Social and Cultural Contributions of Portuguese to the Ironbound (1920s-1970s)

The Portuguese first settled in Newark between the 1890s to 1920s. Many came to work in the Ironbound’s chemical factories, breweries, railroads, and tanneries[1].The Portuguese American populations in Newark as well as in other enclaves in the country grew between the 1950s-1970s after the passing of the Azorean Refugee Act of 1958, which gave amnesty to refugees from the Azorean Islands after a volcanic eruption[2]. The Hart-Cellar Act of 1965, which lifted earlier bans on non-Northern European immigrants, led to the arrival of more immigrants from Portugal[3]. This was also accompanied by socio-political factors under Portugal’s fascist Estado Novo regime, causing more Portuguese to move and settle in the US, and especially the Northeast. As Portuguese settlement to Newark increased, so did their commercial activities. By the 1990s, New Jersey had the fourth largest Portuguese population in the US, by 56,928 people[4]. Portuguese in Newark made up 14,796 and were the largest foreign-born population in the city at the timez. The economic success of the Portuguese community also influenced the increased prominence of Portuguese institutions and individuals.

These institutions remained prominent landmarks in the neighborhood, even throughout urban decline between the 1950s-1960s. As one of the few spaces in Newark that was untouched by the 1967 Riots, the Ironbound developed a large commercial sector which Portuguese institutions capitalized on. According to Holton, Portuguese institutions helped revitalize Newark’s postindustrial economy following the riots through arts, food, and entertainment through the success of their restaurants and the Portugal Day parade[5]. The successes of these cultural spaces encouraged the Portuguese to gradually enter city politics, and eventually activism.

Since their establishment, Portuguese institutions and businesses have contributed to community affairs in the neighborhood. The Portuguese Sports Club on Prospect Street, founded in December 17, 1921, is one of the oldest sports venues in Newark. Portuguese Americans also established numerous other clubs, such as Club Azores on Wilson Avenue. The purpose of the sports club was to preserve Portuguese culture and identity, and to provide a social gathering space for the community. For decades, the sports club has been a cornerstone of the Portuguese American experience in Newark, they organized many cultural as well as athletic activities such as soccer leagues and traditional folklore performances. These activities that the sports club led had an impact on Newark’s economy and also contributed to Portuguese American’s increased political power in the city[6]. This allowed for Portuguese community leaders to host meetings on issues that affected the neighborhood.

Established by immigrants and businessmen Vasco S. Jardim and Fernando Santos in 1928, the Luso Americano newspaper has served the Portuguese American community in Newark, NJ, and in other parts of the US. The Luso has also voiced Portuguese American enclaves outside of Newark such as New York, Massachussetts, Rhode Island, and California. The Luso is printed entirely in Portuguese, as most of the readers did not understand English. This enabled the newspaper to keep the population informed on social and political events.

The Portuguese American Congress, founded in 1983, saw a rise of Portuguese political power in Newark. The PAC’s establishment marked the beginning of Portuguese American’s political representation in Newark, has the city has historically been governed by Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Black politicians. While the PAC was founded primarily to assist Portuguese immigrants in becoming naturalized citizens, seeking employment, and getting them to vote, they gradually became more attentive about environmental issues like the incinerator. The PAC were among the first Portuguese American institutions that responded to the proposed incinerator and stadium in Riverbank Park shortly after their establishment[7]. This was because during these campaigns Portuguese Americans became more vocal in politics through elected officials from their own community. These officials, among them former East Ward councilman and Portuguese leader Augusto Amador, partially gained power because of their action against the fights against the incinerator and the renovation of Riverbank Park.

Portuguese Individuals and the Fight Against Noise Pollution (1970s)

Between 1978-1980, the ICC organized protests against noise pollution caused by flights from planes landing in JFK and Newark airports. This was the first major environmental issue that the Ironbound community acted against[8]. Above planes created excessive noise that harmed the Ironbound community. After weeks of picketing, the ICC finally got the local airlines to shift paths away from the Ironbound. As members of the Ironbound community, Portuguese residents were as concerned about the excessive noise created by the nearby airports. While they acted alongside the ICC, Portuguese made the first step in environmental justice activism simply by joining the ICC’s demonstrations. Since 1977, the ICC began publishing and distributing a monthly newsletter called the Ironbound Voices, which had sections written in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Among the contributors of the Ironbound Voices were Portuguese members of the ICC including Armando Janiera, and Rosa Teixeira. According to ICC leader Nancy Zak, many Portuguese residents and contributors also wrote the Portuguese sections of the Ironbound Voices, which made it accessible for Portuguese readers[9].

Luso Americano, Catholic Parishes, Portuguese Sports Clubs, and Portugal Day Parade Against Ironbound Incinerators (1980s)

Capitalizing on their success from the noise pollution fight, the ICC then turned to solving toxic waste that affected the neighborhood, forming the Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste (ICATW). The ICATW collaborated with both local and national groups, among them the Portuguese institutions, particularly the PAC, continued to play an active role in environmental issues through collaboration with the ICATW. This was especially true with the fight against a proposed garbage incinerator by At Sea Incineration that the city slated to be constructed in the Ironbound. In 1981, the city of Newark approved a proposal by the At Sea Waste company to build an incinerator at Port Newark.

As one of the major residential demographics that lived in the neighborhood, Portuguese Americans were the first to stand up to the proposal. The Portuguese who lived there already faced the pollution in their daily lives. An example of this is Dr. Ana Baptista, a current professor of Environmental Policy at the New School in New York. Baptista was born in Portugal, after emigrating to Newark in 1981, her family like other Portuguese residents in the Ironbound were affected by pollution. Baptista recalled waste from factories being dumped on her neighbor’s yards, especially for her since her family lived next to a steel-drum factory[10]. As a child, Baptista and her parents participated in ICTATW’s protests, where she marched and translated for her parents[11]. These experiences shaped her interest in environmental issues. After graduating Science Park High School in 1994, Baptista went on to study environmental science at Dartmouth, and after earning her degree she then returned to Newark and served as an advisor for the ICC[12].

In an interview with the ICC in 2012, Baptista recounts the challenges of activism in diverse immigrant neighborhoods like the Ironbound. While she mentions the claims made in “When Nature is Rats and Roaches” regarding Portuguese American’s limited involvement in environmental justice due to the need to find employment and not knowing or speaking English, Baptista confirms that Portuguese still cared about environmental problems. Many of the people in the marches she took part in were Portuguese, including her own immigrant parents. She states that it was because Portuguese culture is centered around community and civic responsibility that motivated Portuguese to join activism[13]. While many immigrants like her parents did not always fully understand the issues, they still encouraged their own family members to get involved, simply because they cared about their home.

While following the lead of the ICC, Portuguese residents were among the first to actively fight against the incinerator’s construction. They participated in the ICC’s marches, as ICC leader Nancy Zak recalls a group of brave Portuguese women standing in front of the incinerator construction site[14]. Baptista mentions this story in her interview as well and adds that these women also chained themselves to the front fence of the site to stop trucks from entering[15]. Aside from At Sea, there were also other incinerators by companies such as Covanta and SCA that inspired further resistance by Portuguese residents, many of whom were employed at these plants. Between 1980 to 1981, Portuguese joined other groups such as African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, and whites in several protests against these incinerators.

Among the ways that the Portuguese community got involved in this fight included participating in marches, organizing protests in churches, holding cultural events like the Portugal Day parade, and spreading awareness through Portuguese language news and media[16].The struggle against the At Sea incinerator saw not only a continuation of Portuguese Newarkers in environmental justice activism in the Ironbound, but also the increased engagement from Portuguese institutions.

From Donald M. Karp’s Broad National Bank Collection, Box 16 Folder 1. Photo of ICATW at Portugal Day in summer of 1982. Courtesy of Newark Public Library Charles F. Cummings New Jersey Information Center.

Portuguese Sports Club

The Portuguese Sports Club and Club Azores were the two common venues for the ICC and Ironbound residents to gather and voice their concerns about social issues between the 80s-90s. In light of the incinerator issue, the sports clubs held several meetings and events for the community to take place. While small occurrences, these meetings, fundraisers, and community events each contributed to the larger campaign against the incinerator by sparking action and discussion amongst the Ironbound community. The sports club hosted on November 5, 1982 for a PSA speech with the ICATW, as well as people from a group from Elizabeth called Chemical Control and residents from Love Canal, in Niagara Falls[17]. ICATW leader and researcher Bob Cartwright along with Love Canal representative Lois Gibbs each gave a speech on the problems that toxic waste creates and how an incinerator in the Ironbound would create even more[18].

The sports club also showed the premiere of a documentary called “In Our Water”, which depicted a family in South Brunswick, NJ suffering from pollution in their town[19]. The film was played to inspire Ironbound residents to act against pollution and incinerator fight that was occurring during the time. The sports club also held meetings by Portuguese educators, notably a meeting on October 23 1985, by the Congress of Portuguese American Educators (COPAE). Joe Rendeiro during this time served as COPAE’s president, and he made a speech about concerns over additional dioxin that the incinerator would bring[20]. While COPAE like the PAC were traditionally more focused on education for immigrant communities, they eventually gave their support to larger concerns. These meetings show that the sports club was not only intended for preserving Portuguese culture, but also as a place for the Ironbound community’s voices to be heard on social issues.

Luso Americano Newspaper

Language media is one of the most essential in understanding Portuguese involvement in this issue, as most first and second-generation Portuguese who lived in the neighborhood did not speak or understand English. According to an interview with the former principal of Hawkins Street School and ICATW member Joseph Rendeiro, Portuguese-language radio stations were staples for both first and second generations of Portuguese that lived in the Ironbound since the 1930s[21]. Between the 1960s to 1980s, Portuguese TV and radio stations such as the Voz de Portugal(Voice of Portugal) reported on events that occurred in Newark, even in the 1967 Riots, and on the neighborhood’s conflicts with the At Sea and Covanta incinerators[22]. Since the 70s, Spanish and Portuguese became the most spoken languages in the Ironbound, with the latter even being spread through Portuguese-owned newspapers and clubs.

In “Language Maintenance and Ethnic Survival: The Portuguese in NJ”, Rutgers ethnologist Thomas M. Stephens examines how the Portuguese-related organizations that were established in New Jersey, namely the sports clubs, the Luso Americano, preserved the culture and identity, including the language. There were also Portuguese-language schools that were established by communities in cities such as Newark, Elizabeth, and Perth Amboy[23]. Holton in her book includes data from the 1990 US Census that proves that aside from having the fourth largest Portuguese population, the Portuguese language was spoken by about 55,285 people[24]. This is important for understanding the Portuguese community’s involvement in environmental activism because it shows how they were a large demographic in the state and in Newark.

This is among the major reasons why the ICC’s monthly newsletter, the Ironbound Voices, was published in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, as ways to target the Ironbound’s immigrant demographics. Considering environmental issues, the ICC formed a partnership with the Luso Americano paper as part of their strategies in educating and involving immigrant populations in environmental issues[25]. Through their partnership, the ICC was able to publish feature articles written in various languages, including Portuguese[26]. The Luso Americano reported on the incinerator issue, specifically highlighting the actions of local Portuguese figures and groups that participated.

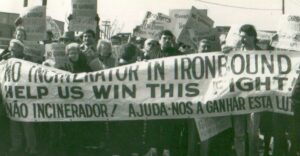

Language was as tool for involvement during the Portugal Day parade. The parade was first organized in 1979 by a family-run organization in the Ironbound called the Coutinho Foundation. The owner, Bernardo Coutinho, was a baker and leader amongst the Luso-American community who helped raise funds to support East Ward councilmen[27]. Based on information from a personal interview with Dr. Ana Baptista, the parade did not always feature protests[28]. However, as the incinerator issue grew worse, the Portuguese addressed these issues in their parade. As leaders of the Ironbound community, the Coutinhos allowed their parade to spread awareness of environmental issues. The most notable Portugal Day protests the At Sea incinerator occurred on June 8th of 1985 and 1986. Both parades saw ICATW members promoting activism against the issue during the march on Ferry Street[29]. This was the 9th Annual Portugal Day that was celebrated in Newark, and during the parade ICATW members had people carrying banners and floats with major headlines in both English and Portuguese that read “No Incinerator in Ironbound! Help us with this fight!”-“Nao Incinerador! Ajuda-Nos A Ganhar Esta Luta![30]”. Residents on the sidelines cheered in support of the protesters while enjoying themselves, and ICATW were even selling colorful balloons that said “No Garbage Incinerators/Nao Incineradores!”[31].

Incinerator protests, 1980s, Newark Public Library Internet Archive

Portuguese radio and TV stations reported on the protests during the parade, and one even interviewed a ICATW marcher who described the organizations “neighbors” i.e. community members like the Portuguese in responding to the campaign against the incinerator. The interviewer further states that they were able to prevent it’s construction because of everyone’s help[32]. This proves that at this point, people in the Ironbound both Portuguese and non-Portuguese were united as a community against the placement of the incinerator. This was further demonstrated in the upcoming dinner fundraiser by the ICATW in more Portuguese spaces.

Portuguese Catholic Parishes

Other than their secular spaces, the Portuguese also allowed community meetings regarding the incinerator issue in their own churches. As Immergut and Kearns write in their article, both Catholic and Protestant parishes in the Ironbound served as meeting spaces for discussions of community issues. While historically churches and religious institutions were only involved with environmental issues to an extent, as they were more concerned with spiritual issues, religious leaders during this period served as sources of moral support and leadership for activist movements[33]. Portuguese Catholic churches such as Our Lady of Fatima on Jefferson street were among the largest parishes in the Ironbound that served the community and also engaged their parishioners in environmental issues.

As the Portuguese and Latinx populations of the Ironbound grew during the second half of the 20th century, many of them took over parishes that were attended by the older ethnic groups that lived Newark between the 1900s-1950s, namely Italians, Irish, and Polish[34]. Portuguese clergy were important in involving their parishioners in environmental justice, as they understood their community. Our Lady of Fatima, like other parishes in Ironbound and Newark worked with other religious institutions like Green Faith and the Ironbound Ecumenical Association, who were committed to assisting environmental justice.

After meeting with Essex County officials regarding the Incinerator, the parish council of Our Lady of Fatima opened discussions up to the public on November 27 1985, believing that the issue was too important to be held privately[35]. Joe Rendeiro and Ana Baptista in their interviews state that Our Lady of Fatima had their own printed newsletter which was distributed to their parishioners in Portuguese[36]. After holding a public meeting, the church most likely would have printed the issue in their newsletter[37].

Portuguese American Congress(PAC)

During the time of the incinerator, the PAC organized their own radio stations in Portuguese that educated residents on health concerns that would be inflicted from waste and fumes, namely cancer, asthma, etc[38].. Following the PAC’s establishment in 1983, ICC leader Vic de Luca interviewed three prominent Portuguese leaders on their talk show, Ironbound Insights. Interviewees included attorney Richard Gomes, journalist Ceu Cerne, and doctor Fausto Simoes. After learning the historical background of Portuguese in Newark, de Luca asks whether the Portuguese community plans on involving themselves in the Incinerator fight, to which they confirm that they contributed.

According to Gomes, members of the PAC did research on the Incinerator, voted 100% opposition to it, and then spoke out against the Board of Freeholders and the Newark city council[39]. Despite these claims however, Gomes states that the passiveness of the Portuguese was what led to the Incinerator being reserved for the Ironbound[40]. Despite earlier accomplishments by community leaders like Vasco Jardim and Fernando Santos, Gomes further explains that Portuguese were ignored throughout their time in Newark, which was due to concerns over gaining citizenship and not knowing English[41]. This is in turn helped increase voting for Portuguese residents[42].

Gomes, Simoes, and Cerne go on to defy common notions of Portuguese as De Luca asked them about their role in the city. This commentary was important because while the Portuguese may not have been as directly active as the ICC in solving environmental issues, their struggle to gain acknowledged as a community coincided with the struggle against those issues. When asked by De Luca if the Portuguese ran their own in city and state politics, Simoes comments that Portuguese economic power can be used to accomplish political changes. This extends to environmental issues, which directly affected the community.

The ICC understood the help that the large Portuguese community could provide in the Incinerator fight. As more people such as Joe Rendeiro and others got involved, so did their institutions. In 1984, a restaurant called O Campino’s on Prospect Street hosted a fundraiser dinner for the ICATW’s fight against the Incinerator. De Luca interviewed several people at the fundraising event, including Portuguese, on whether the community is committed to preventing the Incinerator’s construction.

During the beginning of the dinner, ICATW leader Arnold Cohen made a speech stating the Ironbound’s commitment to stopping the Incinerator’s construction, fellow organizer Rosa Da Costa translated in Portuguese[43]. PAC member and Newark businessman Art Rosa revealed that Portuguese were informed of the Incinerator issue through the Luso Americano, and he claimed that Portuguese support for the ICATW was “unbelievable”[44]. Rosa further states that because of the controversy surrounding the Incinerator proposal, over 1,000 Portuguese residents began to organize and register to vote[45]. Rosa states that the Incinerator issue brought people “together”, including Portuguese in the Ironbound, and that the PAC was committed to raising funds to fight the proposal[46]. Resident Anita Da Silva states that the Portuguese community has been very “forceful” in the Ironbound, and that they have “more or less built” the neighborhood along with other ethnic groups[47].

Rosa and Da Silva’s comments as well as the setting of the fundraiser demonstrates the increased social/political power that the Portuguese had in Newark considering the Incinerator issue. These events were major turning points for the Portuguese in Newark, as they have been underrepresented in city and state politics.

Portuguese American Congress (PAC) and Riverbank Park(1996-1999)

Since their contributions to the struggle against At Sea’s Garbage Incinerator and pollution, Portuguese institutions have become regular public servants to the Ironbound neighborhood’s community. This has in turn led to an increase in Portuguese political power, as figures and leaders Augusto Amador, Albert Coutinho, Irene DeOliveira, were elected as representatives of the East Ward through their commitment to solving environmental and infrastructural issues that affected the Ironbound neighborhood.

This is proven through collaboration with SPARK and the ICC in saving Riverbank Park. Since it’s construction in 1909 by architect Frederick Law Olmstead, Riverbank Park has served as an important recreational park for the Ironbound community. However in late 1995, the manager of the Newark Bears Minor League baseball team and former MLB catcher Rick Cerone announced the construction of their new ballpark in Riverbank Park. After news of the Bears’s ballpark reached the Ironbound, the community immediately held meetings at Club Azores and Iberia restaurant on Ferry Street[48]. Among the people who attended these were representatives from the PAC. After the success from preventing the incinerator’s construction, the PAC led efforts to protect Riverbank Park. The PAC took an even more active position in stopping Riverbank Park’s renovation by partnering with more local groups like SPARK, and by passing helping to pass legislation through community-held referendums, and by electing their own members into Newark’s municipal government, namely Augusto Amador, Art Rosa, and Diana Silva.

Portuguese residents acknowledged the environmental issues that the Newark Bear’s ballpark would cause, as they would have endured increased traffic and pollution from cars. However, they also opposed the ballpark for cultural reasons, as soccer rather than baseball was the popular sport in the neighborhood. Both environmental and cultural concerns motivated Portuguese residents in joining the fight along with SPARK. As with the ICC in the fight against the Incinerator, SPARK’s success relied on the support of the resident immigrant population in preserving Riverbank Park. This was because Riverbank Park as one of the few recreational spaces that were saved in the Ironbound was important to the neighborhood’s immigrants, among them the Portuguese.

Portuguese article about Riverfront Park, 1995, Newark Public Library Internet Archive

Like other ethnic groups that lived in the Ironbound, Riverbank Park was important for the growth of their young athletes. This was especially true for the Portuguese, who founded many soccer leagues that still exist in the Ironbound today, such as the Ironbound Strikers Club by Albert Coutinho, Joseph Rendeiro, and Augusto Amador[49]. Portuguese attachment to the Park goes back to 1931, as the Portuguese Sports Club organized a traditional dance performance to celebrate the park’s reopening after its expansion. Years after the Park was saved, but was closed due to soil contamination, an article from the Luso Americano in 1999, “O Riverbank Park e Ironbound Stadium tiveram um papel crucial a nossa evolucao como atletas e como jovens(Riverbank Park and the Ironbound are crucial for our growth/evolution as athletes and kids”[50] commented on the importance of Riverbank Park for young athletes growing in the Ironbound. The title was a quote by a resident named Jorge Lopes, who grew up playing soccer in the park. Lopes’s story demonstrates the value that the park had for the Portuguese community, and that they were willing to defend it.

After residents in the Ironbound learned of the park’s renovation, a series of meetings were held in the neighborhood’s most well-known cultural venues. Among them of course were Portuguese-owned, which were at this point becoming regular community meeting spaces. These included Club Azores on Wilson Ave and the Iberia Restaurant on Ferry Street, which became some of the first community meeting spots for discussions of the renovation[51]. These were soccer clubs, which was the main sport that was played in Riverbank Park. These factors helped motivate the clubs to protect the park.

Around the same time as the protests during Portugal Day in July of 1996, members of the Ironbound Little League, Boys and Girls Clubs, and several Portuguese-owned clubs and organizations gathered at the Wolff Memorial Presbyterian Church. They organized a referendum a year later in the same church on November 1997, which was sponsored by both the PAC and SPARK[52]. The church also held a community meeting discussing a proposal by Ironbound businessman Steve Rappaport for a Special Improvement District (SID) of the neighborhood for increased funds for public improvement projects.

This meeting was met between members of SPARK, the PAC, and the Portuguese American Political Party (PAPP). This meeting highlighted not only the collaboration between Portuguese organizations and grassroots activists, but also Portuguese politician’s commitment to handling infrastructural issues in the Ironbound. Art Rosa, who was present during the meeting, commented on how the Ironbound historically never had a choice about policies or projects had had that were proposed in the neighborhood, as they were traditionally done either by Newark city councilmen or people outside of the city[53]. Members of the PAC and SPARK sponsored a recreational study by NJIT’s Architecture department starting on November 1997. This was for building a replacement ballpark in Riverbank Park, where NJIT students drew and submitted drawings and designs to a subcommittee made up of SPARK and PAC members such as Nancy Zak, and Art Rosa.

As the meetings and commentary from Portuguese officials and groups suggest, the community became more active in politics, with the election of Augusto Amador as the East Ward’s councilman on July 1 of 1998[54]. Amador was born in Murtosa, Portugal in 1949, and emigrated to Newark in 1966[55]. He was the first Portuguese American to be elected in Newark’s government in the city’s history, after defeating incumbent Hank Martinez[56]. As a Portuguese American who lived most of his life in the Ironbound, Amador understood the problems that faced his community. He was also a leader in the PAC as a longtime Portuguese community member. His role in saving Riverbank Park and working with the ICC and SPARK helped him into power, and it demonstrated the increased political power that Ironbound residents, among them Portuguese had against environmental issues.

Construction of the Bear’s ballpark stopped in winter of 1998 after a combination of SPARK’s numerous demonstrations and Rick Cerone deciding to move it to Broad Street[57]. Riverbank Park however was closed after the soil became high levels of lead and arsenic[58]. As the East Ward’s recently elected councilman, Amador chaired a series of meetings at the Portuguese Sports Club alongside the PAC and SPARK[59].

Conclusion

Hundreds continued to cheer as the SPARK protesters marched down Ferry Street. The Portugal Day parade of 1996 had a huge turnout from people of different backgrounds, both from and outside of Newark. For the past 18 years leading up to protests against Riverbank Park’s renovation, the Portugal Day served as both a celebration of Portuguese culture and heritage and a community-building event for Ironbound residents. As residents of the Ironbound, Portuguese Americans not only contributed, but also directed campaigns against pollution, the proposed At Sea incinerator, and the renovation of Riverbank Park through their own culture. This period of activism coincided with the maturation of Newark’s Portuguese American population as upstanding citizens and political leaders.

As this paper previous explored, the Portuguese directed the Ironbound community’s activism through their culture and institutions during three key environmental justice campaigns. The first step of their Portuguese involvement was when individuals simply joined in on the ICC’s protests during the battle against noise pollution between 1978 to 1980. Between 1980-1985, Portuguese became more responsive and unified towards environmental and social issues through organized meetings at their sports clubs and churches, informing community members through the Luso Americano and Ironbound Voices, advertising the issue through the Portugal Day parade, and the PAC coordinating programs and fundraisers.

These actions further demonstrate that Portuguese Americans, while historically known as a passive towards politics due to the cultural and economic barriers, were outspoken on environmental issues in their home. Jumping ahead towards the 90’s, the Portuguese community at this point were represented by elected officials many of whom gained power by holding programs, referendums, and events alongside the ICC and SPARK in response to redevelopment. It was through environmental justice that Portuguese became a more visible community in Newark politics, and overtime they became major leaders in the city. While many most Portuguese left Newark for the suburbs between the late 1980s to early 1990s, many are still active in city politics today.

Most scholars on Newark’s history and cultures have not paid enough attention to Portuguese Americans in environmental justice because they lacked the same representation in politics as other ethnic groups. Some of the primary sources of this paper, particularly the ICC’s interview with Ana Baptista and the Ironbound Insight’s episode with the PAC confirmed some of the points that were raised in “When Nature is Rats and Roaches” about Portuguese focusing on citizenship and employment.

However, they both highlighted that it was because of those cultural and economic barriers that created the notion of Portuguese being passive, and “aloof” towards political issues[60]. Portuguese Americans have also been primarily known for their cultural activities that they led in Newark, which is what Kimberly Da Costa Holton explored in Community, Culture, and the Makings of Identity. By viewing solely the cultural factors through their famous restaurants and clubs however, scholars have overlooked the fact that as a prominent ethnic group in the city during the late 20th century, Portuguese were actors in city politics.

The sources further point out that as residents of the Ironbound, Portuguese alongside African-Americans and Latinx were among the first to act against issues like the incinerator or Riverbank Park. Portuguese cultural activities that were popular in the neighborhood for decades such as the parade were spaces where the Ironbound’s voices were heard against issues that affected their neighborhood. This is seen through various photographs and newspaper articles on the floats, banners, and signs in English and Portuguese demanding the Newark city government to save the park.

This essay is useful for understanding how certain ethnic groups engage in activism. Portuguese Americans in Newark are an interesting case in this scholarship because while they lacked positions in institutions such as the Newark Municipal court, they played their part in activism through their own spaces; namely churches and clubs, where the rest of the Ironbound was included in. This demonstrates that as longtime residents of the Ironbound, Portuguese Americans cared about their home, and were willing to work with the entire community in defending it.

ENDNOTES

[1] Charles F. Cummings, “Roots of the Portuguese in Newark Can Be Found in Three from Old Guard,” The Star Ledger, June 5, 1997, Newark Public Library, https://knowingnewark.npl.org/roots-of-the-portuguese-in-newark-can-be-found-in-three-from-old-guard/.

[2] Maria Gloria Mulcahy, “The Portuguese of the United States from 1880 to 1990: Distinctiveness in Work Patterns across Gender, Nativity and Place,” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (Ph.D., United States — Rhode Island, Brown University, 2003), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (305346720), https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fdissertations-theses%2Fportuguese-united-states-1880-1990%2Fdocview%2F305346720%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.Pg.31.

[3] Maria Gloria Mulcahy, “The Portuguese of the United States from 1880 to 1990: Distinctiveness in Work Patterns across Gender, Nativity and Place,” Pg31. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (Ph.D., United States — Rhode Island, Brown University, 2003), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (305346720),https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fdissertations-theses%2Fportuguese-united-states-1880-1990%2Fdocview%2F305346720%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

[4] Kimberly. DaCosta Holton and Andrea. Klimt, Community, Culture and the Makings of Identity : Portuguese-Americans along the Eastern Seaboard, Portuguese in the Americas Series ; 11 (North Dartmouth, Mass: University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Center for Portuguese Studies and Culture, 2009), https://www.umasspress.com/9781933227276/community-culture-and-the-makings-of-identity/.Pg.154.

[5] DaCosta Holton and Klimt.Pg. 147.

[6] DaCosta Holton and Klimt.Pg.168.

[7] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress,” Ironbound Insights, January 9, 1985, Ironbound Environmental Justice History Resource Center, Newark Public Libary- Van Buren Branch, https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1m4mB555w9thZbuZfeliDVzuukVkiUY18.

[8] Luke W. Cole and Sheila R. Foster, From the Ground up : Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement, 1st ed., Critical America (New York: New York University Press, 2001), https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814772294. pg. 157.

[9] Nancy Zak, Interview with Nancy Zak, In-person, Voice Memos, March 19, 2025.

[10] Interview with Anan Baptista, Video Interview (ICC, 2012), https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1xAPAq1HPvv9S8bk3nn59HE4vummg2vak.

[11] Interview with Anan Baptista.

[12] Interview with Anan Baptista.

[13] Interview with Anan Baptista.

[14] Interview with Nancy Zak, In-person, Voice Memos, March 19, 2025.

[15] Interview with Ana Baptista.

[16] Interview with Joe Rendeiro, In-person, April 1, 2025.

[17] “”Love Canal Resident Says ‘Stand Together and Say No,’” Ironbound Voices, November 1982, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198212a/page/n1/mode/2up.

[18] “”Love Canal Resident Says ‘Stand Together and Say No.’”

[19] “Don’t Let Them Dump on You,” Ironbound Voices, September 1982, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198209a/page/n5/mode/2up.

[20] “Fight Against Incinerator Grows Stronger,” Ironbound Voices, Internet Archive, Newark Public Library, accessed May 4, 2025, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198511a/page/n1/mode/1up?view=theater.

[21] Interview with Joe Rendeiro, In-person, April 1, 2025.

[22] Interview with Joe Rendeiro.

[23] Thomas M. Stephens, “Language Maintenance and Ethnic Survival: The Portuguese in New Jersey,” Hispania 72, no. 3 (1989): 716–20, https://doi.org/10.2307/343531.Pg.717.

[24] DaCosta Holton and Klimt, Community, Culture and the Makings of Identity : Portuguese-Americans along the Eastern Seaboard.Pg.154.

[25] Nancy Zak, Interview with Nancy Zak.

[26] “The Work Goes On!,” Ironbound Voices, January 1984, Vol. 6 Number 8 edition, Internet Archive, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198401a/mode/2up?view=theater.

[27] Charles F. Cummings, “Roots of the Portuguese in Newark Can Be Found in Three from Old Guard.”

[28] Interview with Anan Baptista.

[29] “Ironbound Marches Against The Incinerator,” Ironbound Voices, July 1986, Vol. 9 No. 3 edition, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198607a/mode/2up?view=theater.

[30] “Stopping Toxic Waste,” Ironbound Voices, July 1986, Vol. 9 No. 3 edition, Internet Archive, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices198607a/mode/2up?view=theater.

[31] “Ironbound Marches Against The Incinerator.”

[32] “Ironbound Marches Against The Incinerator.”

[33] Matthew B. Immergut and Laurel D. Kearns, “When Nature Is Rats and Roaches: Religious Eco-Justice Activism in Newark, NJ,” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 6, no. 2 (2012): 176–95, https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.v6i2.176. Pg. 184.

[34] Joseph Rendeiro, Interview with Joe Rendeiro.

[35] Immergut and Kearns, “When Nature Is Rats and Roaches: Religious Eco-Justice Activism in Newark, NJ.”Pg.186.

[36] Interview with Joe Rendeiro, Interview with Dr. Ana Baptista.

[37] I was unable to find any copies of Our Lady of Fatima, so I made the logical assumption that since the church was attentive about issues that affected their neighborhood, they most likely would have mentioned it in their newsletter.

[38] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

[39] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

[40] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

[41] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

[42] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

[43] Dinner Dance Fundraiser for the ICATW & Newark Emergency Services for Families ICATW Dinner Dance., Video Interview, 1984, https://newarkpubliclibrary.libraryhost.com/repositories/7/archival_objects/103289.

[44] Dinner Dance Fundraiser for the ICATW & Newark Emergency Services for Families ICATW Dinner Dance.

[45] Dinner Dance Fundraiser for the ICATW & Newark Emergency Services for Families ICATW Dinner Dance.

[46] Dinner Dance Fundraiser for the ICATW & Newark Emergency Services for Families ICATW Dinner Dance.

[47] Dinner Dance Fundraiser for the ICATW & Newark Emergency Services for Families ICATW Dinner Dance.

[48] “A Foul or Homer: A Baseball Stadium in Ironbound,” Ironbound Voices, 1995, sec. Fall 1995 Vol., Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1995Falla/page/4/mode/2up.

[49] Interview with Joseph Rendeiro, Interview with Joe Rendeiro.

[50] English translation: Riverbank Park and Ironbound Stadium played a crucial role in our evolution as athletes and as kids.

[51] “A Foul or Homer: A Baseball Stadium in Ironbound.”

[52] “SID Proposal Opposed,” Ironbound Voices, 1998, Fall 1997 edition, Internet Archive, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1998Wintera.

[53] “SID Proposal Opposed.”

[54] Vasco S. Jardim, “Amador Foi Eleito No Bairro Leste De Newark,”(Amador was elected in Newark) Luso Americano, May 13, 1998, Luso Americano 1990s, Newark Public Library.

[55] Fernando Dos Santos, Os Portugueses em New Jersey (Luso Americano, n.d.).Pg.

[56] DaCosta Holton and Klimt, Community, Culture and the Makings of Identity : Portuguese-Americans along the Eastern Seaboard. Pg. 169.

[57] “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning,” Ironbound Voices, 1998, Newark Public Libary, https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1998Wintera/page/8/mode/2up?view=theater.

[58] “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning.”

[59] “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning.”

[60] “Interview with Portuguese American Congress.”

Primary Sources:

1. Haulsley, Kuwana. “Architecture Work Lets Students Build Ironbound Dreams.” The Star Ledger, April 23, 1998. Newark Parks- Essex Co. Parks. Newark Public Library. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AD&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=20&val-base-0=architecture%20work%20lets%20students%20build%20ironbound%20dreams&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=1998&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-1710ECBBE474B1B7%402450927-1710E6901BA7B36E%40114-1710E6901BA7B36E%40

In 1998, there was a study done by Architecture students from NJIT to propose new designs for recreational spaces. Those designs were submitted to a committee made up of members from the ICC, the Portuguese American Congress, and residents. Students did research on spaces that needed recreation or improvement in it and then presented their projects to the ICC. The fact that the Portuguese Congress was one of the recipients of these projects highlights that they were very much involved in community decision making in the Ironbound, especially when it came to recreation.

2. Ironbound Voices. “A Foul or Homer: A Baseball Stadium in Ironbound.” 1995. Newark Public Library. https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1995Falla/page/4/mode/2up

This news article by the Ironbound Voices catalogue discusses the construction of a new baseball stadium in Riverbank Park. Between the 1980s-1990s, the Newark city government oversaw projects in the Passaic River area to attract revitalize the city’s economy and bring consumers back. Most Ironbound residents opposed this new project, due to concerns about parking, traffic, and reduction in recreational space. Meetings to discuss the construction of the new ballpark were held in Club Azores and the Iberia restaurant, which were Portuguese-owned businesses. These two institutions were popular venues, but in this case they also served as meeting grounds for the Ironbound community. I argue that since meetings were held in these spaces, Portuguese Americans in the Ironbound were active in the issues that affected their neighborhood.

3. Ironbound Voices. “People Making History: Our Neighborhood and Our Tax Money- A Chance to Vote March 11 about the Future of Riverbank Park.” 1997. Newark Public Libary. https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1997Wintera/page/2/mode/2up.

Portuguese Club holds meeting by Essex County Freeholders on December 10 as well as the referendum on the construction that would take place in March the following year. The fact that the Portuguese Sports Club was a venue for the community to discuss the issue of Riverbank Park proves that the Portuguese were actively involved.

4. Ironbound Voices. “Riverbank Park Fight Gains Steam.” 1996. Newark Public Library. https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1996Summera/page/6/mode/2up

The summer newsletter of 1996 discusses the intensity of the Ironbound’s opposition to stadium development in Riverbank Park. Members of various community organizations, including the ICC, Ironbound Boys and Girl Clubs, and Portuguese Clubs and Organizations form the Save Riverbank Park Coalition (SPARK). Meetings were then held in the Wolff Memorial Church. Actions SPARK takes to fight the construction included rallies by English, Spanish, and Portuguese-speaking residents of the Ironbound. Portuguese-speaking residents were actively involved in the fight to save Riverbank. The newsletter also includes commentary by various residents and activists of what they think of the issues. These include ICC leader Nancy Zak and East Ward Councilman and Portuguese American Augusto Amador, the latter of whom stated that “some people are taking advantage of the community. This league is in formation. What happens when the team folds, and we are left with 2 stadiums, but no park?”. This quote demonstrates that Lusophone residents like Amador were outspoken about the issue of stadium construction.

5. Ironbound Voices. “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning.” 1998. Newark Public Library. https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1998Wintera/page/8/mode/2up?view=theater

After the demolition of Riverbank Park was stopped, SPARK became focused on reopening park after it was closed due to soil contamination from nearby pollutants. SPARK and the ICC held several meetings for a proposal that was first made in the previous year 1997 called the Special Improvement District(SID). This was first held in a community meeting in Wolff Memorial Church, and was sponsored by Portuguese individuals and organizations, including the Portuguese American Congress, and the Portuguese American Political Party. The newsletter includes commentary by PAC and PAPP members Art Rosa and Dina Matos, the wife of future NJ governor Jim McGreevey, basically stating that the community of the Ironbound must and should have more decision-making in their own neighborhood rather than outsiders. By highlighting the involvement and perspectives of notable Luso Americans, this article demonstrates that Luso Americans were concerned and proactive with issues that affected the Ironbound, and that they as members of the neighborhood contributed to the fight against outsider-led redevelopment.

6. “Melhor, e Neo Destruir o Nosso Parque,” n.d.Newark Public Library https://archive.org/details/Ironbound0224.

This sign, translated to “Fix, don’t destroy our park”, was most likely made to address Portuguese or Brazilian residents when the plans for construction in Riverbank Park began in 1996. It may have also been written by a Portuguese-speaking resident as a call to action to other members of the community.

7. “Riverbank Park Protests,” Newark Public Library, https://archive.org/details/Ironbound0220.

This photo was taken during the annual Portugal Day parade in Newark in 1998. Here SPARK organized a protest during the parade in reaction to the closing of Riverbank Park due to contamination. Portugal Day is a popular festival in Newark that honors Portuguese heritage and culture. It has also been a space for community organizing against environmental issues, including the fight against the garbage incinerator in the 1980s. Because the parade is organized by Portuguese figures and institutions, having protests during this time demonstrates that Portuguese Americans were supported activism in the Ironbound.

8. Stewart, Nikita. “Reopening of Newark Park Ends Long Fight.” The Star Ledger, November 6, 2003. Newark Parks- Essex Co. Parks. Newark Public Library. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AD&maxresults=20&f=advanced&val-base-0=riverbank%20park&fld-base-0=alltext&bln-base-1=and&val-base-1=2003&fld-base-1=YMD_date&docref=image%2Fv2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-1720C37FB80D18A2%402452950-171E5C86623008D4%4031&origin=image%2Fv2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-1720C37FB80D18A2%402452950-1720B51307A53FF5%4030-1720B51307A53FF5%40.

This Star Ledger discusses the reopening of Riverbank Park after soil contamination. Most of the focus was on SPARK leader Nancy Zak, who after the reopening continued to champion for more recreational space in the Ironbound’s parks. When reflecting on the fight to save Riverbank Park, East Ward Councilman Augusto Amador said the event was an “exercise in democracy”. This shows highlights the role that while not always the leading figures in Riverbank Park’s preservation, Portuguese Americans were still actively involved in it.

Walsh, Diane C. “Riverfront Plan Unveiled.” The Star Ledger, April 16, 1998. Newark Parks- Essex Co. Parks. Newark Public Library. 9. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AD&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=20&val-base-0=riverfront%20plan%20unveiled&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=1998&docref=image/v2%3A14245EE216D1AED8%40EANX-NB-1710E9ECE68D2727%402450920-1710E62651C3FB09%4050-1710E62651C3FB09%40

This article discusses the construction of a new park near Riverbank Park called Riverfront Park, which was designed to expand recreational space in the neighborhood. While initially meant as the replacement park for Riverbank, the plans for Riverfront Park were repurposed as an additional recreation space for the Ironbound neighborhood. Unlike the earlier development of Riverbank Park, residents including the Ironbound Strikers Soccer Club President Albert Countinho were excited by the prospects of Riverfront Park. The new park was expected to have a new soccer field, which pleased many Portuguese immigrants, as well as Coutinho, who needed more space for the youth teams he coached. Councilman Amador previously chaired meetings to discuss the new recreation site, saying “There is a tremendous appetite for soccer, baseball, and football in the Ironbound. But unfortunately, recreation sites have been basically nonexistent”. This demonstrates how the Portuguese community had a strong impact on recreation in their own neighborhood.

10. Walsh C. Diane “Ironbound Gets a Place to Play Ball.” Star Ledger, 1998. Newark Parks- Essex Co. Parks. Newark Public Library.

This article announces plans to build Riverfront Park, to increase recreational space for the Ironbound. This was during the same time the NJPAC was established. Article has positive commentary from a resident named Albert Coutinho an assemblyman from the Ironbound who also the coached youth soccer club called Ironbound Strikers. The article mentions that because this is an expansion for a soccer stadium, Portuguese American residents would excited by the prospect. Coutinho, who is Portuguese American, demonstrates how the project unlike the demolition of Riverbank Park received support from the Luso community.

Primary Source Analysis:

An article of the Ironbound Voices of the Winter 1998 newsletter, “SID Proposal Opposed” discusses a proposal that was made by the Ironbound community after Riverbank Park was saved from demolition. This measure issued a Special Improvement District (SID) that was intended to generate $1.5 million a year to help clean Riverbank Park after it’s soil became contaminated through a surcharge on all Ironbound businesses. The money would also be used for beautification projects, street clean ups, extra security, etc.

The community debated on the SID in an earlier meeting from November 19, 1997 in the Wolff Memorial Church, which was sponsored by members of the Ironbound Community Corporation(ICC), as well as from Portuguese American institutions such as the Portuguese American Congress(PAC), and the Portuguese American Political Party(PAPP). Among the members of those organizations that were present during the meeting were Art Rosa and Dina Matos from PAPP and PAC respectively, who commented on the prior decision-making on infrastructural projects in the Ironbound not being made by people in the community.

Based on the information in this article and newsletter and the involvement of two prominent Portuguese American groups in the Wolff Memorial Church meeting, I argue that Portuguese-American residents in the Ironbound were active in environmental issues that afflicted the neighborhood. The same as well as other newsletter between 1996 to 1998 mention that the PAC and PAPP were involved in organizing for Riverbank Park, such as chairing community meetings or sponsoring events such as the Recreation Roundtable study that was conducted by NJIT architecture students in the same year. While not mentioned in this article, the previous “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning” mentions how city councilman Augusto Amador, a known Portuguese Ironbound resident, worked with various recreational groups and community organizations in forming a plan to properly manage Riverbank Park and other spaces.

The following quotations by Art Rosa and Dina Matos, who attended the Wolff Church meeting and presumably others demonstrated commitment to solving the issues of recreation as well as the necessity for collaboration with other organizations. Rosa comments in the newsletter saying that “One of the problems in Ironbound is that we never had a choice about the things which are proposed in our neighborhood”. This quote not only refers to how decision-making over projects like recreation or infrastructure were made by non-residents or people within Newark’s city gov’t, but also that Rosa as resident of the Ironbound felt neglected as others about those projects.

In a more positive note, Dina Matos, comments on how the different community groups were able to host the meeting, stating that “If we work together, we can accomplish a lot”. There is plenty of past evidence of the various groups collaborating on saving Riverbank Park, such as the ICC holding meetings at the Portuguese Sports Club on Congress Street, which was a popular venue for community members of all backgrounds. Portuguese-owned businesses were also the most successful in the Ironbound, and their money would have been valued in forming improvement projects and programs in Riverbank Park after its reopening.

While the SID faced pushback from several figures, such as Councilman Henry Martinez, it did receive overwhelming support from residents of the Ironbound community. Among those residents were Portuguese Americans. They, along with other members of the neighborhood community, played essential roles in the decision-making behind establishing recreational projects.

Source:

Ironbound Voices. “Riverbank Park: A New Beginning.” 1998. Newark Public Library. https://archive.org/details/IronboundVoices1998Wintera/page/8/mode/2up?view=theater

Secondary Sources:

1. DaCosta Holton, Kimberly., and Andrea. Klimt. Community, Culture and the Makings of Identity : Portuguese-Americans along the Eastern Seaboard. Portuguese in the Americas Series ; 11. North Dartmouth, Mass: University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Center for Portuguese Studies and Culture, 2009. https://www.umasspress.com/9781933227276/community-culture-and-the-makings-of-identity/

This book is an ethnographic study of Portuguese American emigration and culture in the East Coast between the early-mid 20th century. It is written by Lusophone Studies scholars Kimberly Da Costa Holton of Rutgers-Newark and Andrea Klimt of UMASS in Dartmouth. While the book is a broad study on Portuguese Americans, Holton and other scholars dedicate chapters on the diaspora in the Ironbound neighborhood of Newark as well as other cities in Northern New Jersey such as Elizabeth and Kearny. Holton and scholars argue overall that Lusophone Studies has not only received few scholarly attentions but also that centering on the Portuguese diaspora adds to historical understandings of 20th century immigration. In the case of New Jersey during the 1960s-1970s, Portuguese Americans as well as Portuguese-speaking peoples have contributed to cultural movements as urban politics, primarily in Newark. This book will serve as an in-depth look of the history of Portuguese Americans in Newark, which will support my research on their roles in Environmental issues. I will pull from the sources including from local institutions such as the Portuguese language Luso Americano paper as well as previous ethnographic research by scholars for Rutgers-Newark’s Ironbound Oral History Project in 2001.

2. Mulcahy, Maria Gloria. “The Portuguese of the United States from 1880 to 1990: Distinctiveness in Work Patterns across Gender, Nativity and Place.” ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Ph.D., Brown University, 2003. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (305346720). https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fdissertations-theses%2Fportuguese-united-states-1880-1990%2Fdocview%2F305346720%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

This dissertation provides a broad history and study of Portuguese in the US from 1880-1990. Mulcahy examines the socio-economic factors of Portuguese migration, specifically how unlike many other European immigrants were more financially-established due to their entrepreneurial mindset. Like Kimberly Da Costa Holton, Mulcahy states that Portuguese settlement represents a break from scholarship of immigration history, as the largest influx came after the 1960s. Through comparison to other ethnic European immigrants, such as Italians, Mulcahy also attributes the success of Portuguese settlement to their resistance to cultural assimilation. This dissertation is important for my work because it provides context of the Portuguese diaspora in the US, and is crucial in understanding how they function in society. This is especially useful when examining Portuguese residents in the Ironbound, many of whom were prominent business-owners and politicians, and how they contributed to their neighborhood.

3. Troiano, Laurel T. “Give Me a Ballpark Figure: Creating Civic Narratives Through Stadium Building,” n.d. 2017, https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/55294/

This dissertation examines the history and politics behind stadium construction in Newark through the perspectives of urban residents. Troiano dedicates two sections on the controversy surrounding the construction of a baseball stadium in Riverbank Park in the late 90’s. In 1995, former Yankees player Rick Cerone cooperated with the Newark City Council to establish a minor league team in Newark through the construction of a new replacement stadium in Riverbank Park. Many of the concerns that were raised amongst residents and representatives of the Ironbound was the amount of traffic and lack of recreational space that the replacement park would bring. The fact that it was proposed as a baseball stadium was not favored by Ironbound residents, majority of whom were ethnic immigrants that played soccer. This source is important for my bibliography because it analyzes the background of stadiums as projects of urban development and renewal. It also highlights the role that SPARK and the Ironbound’s community organizations played in preserving Riverbank Park, as well as how residents reacted to this development.

4. Stephens, Thomas M. “Language Maintenance and Ethnic Survival: The Portuguese in New Jersey.” Hispania 72, no. 3 (1989): 716–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/343531.

This article is an ethnographic study of Portuguese communities and cultures in northern New Jersey with a focus on linguistics. Scholar Thomas M. Stephens argues that Portuguese Americans were able to retain their language and ethnic ties to their homeland while living in the US. Stephens illustrates how between the 1960s-1980s, Portuguese communities in Newark, Elizabeth, and Harrison kept their culture and language alive through various forms of media and social organizations. These include Portuguese-printed newspapers such as the Luso Americano in the Ironbound, Catholic Churches like Our Lady of Fatima in Elizabeth, Portuguese language schools and sports clubs in both cities. Despite many Portuguese moving to Newark and Elizabeth suburbs like Kearny, Watchung, etc during the 1980s, they were able to maintain their culture. This article illuminates not only methods of cultural preservation among ethnic groups in New Jersey, but also the socio-economic power that recent immigrant groups like the Portuguese had in the state.

8. Stevenson Jason Reich. “The Fire This Time: Development Conflict in Rebuilding Newark, NJ.” Harvard College, n.d. 2000 http://webatomics.com/jason/seniorthesis.html

This undergraduate thesis discusses the areas of conflict in venue development in Newark between the 1990’s to the early 2000s. Stevenson specifically looks at how Newark’s communities and organizations reacted to developments including Riverbank Park in the late 90’s, the NJPAC, and the Prudential Center in 2007. Like Troiano’s dissertation on stadium development, Stevenson’s dissertation will support my research by contextualizing urban development through the ground level perspectives.

9. Stevenson Jason Reich. “Arena Politics in Newark,” 2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20061112062402/http://webatomics.com/jason/newarkarena.pdf

This article expands on his prior undergraduate thesis on stadium politics in Newark. In this article however, Stephenson focuses more so on community leaders such as Augsto Amador, a Portuguese American councilman from the Ironbound who opposed then-Mayor Sharpe James on stadium construction. This was written in 2004, during the administration of Mayor James. While focusing on the Prudential Center, Stevenson’s article would serve as a point of comparison to the earlier development of Riverbank Park, especially when discussing the politics behind stadium construction.

10. Immergut, Matthew B., and Laurel D. Kearns. “When Nature Is Rats and Roaches: Religious Eco-Justice Activism in Newark, NJ.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 6, no. 2 (2012): 176–95. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.v6i2.176.

This article discusses the role those religious institutions played in Environmental Justice in the Ironbound. Despite past scholarship stating that religious institutions were ore concerned with spiritual rather than environmental issues, the scholars instead argue that clergymen from churches such as St. Stephans Church and Our Lady of Fatima were essential actors against pollution in the Ironbound. Many clergymen helped found several community-based groups that are still active today, such as the Ironbound Community Corporation, Green-Faith, etc. Priests and pastors helped manage campaigns, hosted meetings to discuss pollution or development issues like the baseball diamond construction in Riverbank Park. This article is useful for my research because it foregrounds the moral leadership behind Environmental Justice in the Ironbound. The article is also relevant because the scholars credit the clergy, many of whom were Eastern Europeans that left Newark before the 1960s, over the Portuguese and Brazilians that came during the late 20th century. They dismiss Lusophone immigrants, stating that they were more concerned with work and finding employment than activism. Because the goal of this paper is to prove that Lusophone immigrants were involved in activism, I will be in direct conversation with this piece.

Image Analysis:

These images all center on the chosen Environmental Justice site; Riverbank Park. They depict and show a change over time in Riverbank Park through a 67 year difference, demonstrating the Portuguese community’s relationship with Riverbank Park in the Ironbound. The top photo was taken on June 12, 1931, depicting a dance organized by the Portuguese Sports Club, titled “Dedication to Riverbank Park”. The second was taken in the summer of 1997 during a vigil that the community held on Ferry Street in protest the park’s renovation for a new stadium for the Newark Bears minor league team. Ferry Street throughout Ironbound history was the heart of Portuguese Newark, and was also a common protesting ground for both local and organizational activists against environmental issues. Based on the contrast and detail of these two images, I argue that these photos demonstrate that throughout time, the Portuguese culture and identity were essential in preserving Riverbank Park as a landmark in the Ironbound.

1931 photo

The park was established in 1909 by the Olmstead Brothers Firm. It was later expanded between 1927-1931 as a recreational space, where the city then organized a reopening celebration. As one of the largest cultural institutions in the neighborhood, the Portuguese Sports Club, which was founded in 1928, led a performance of a traditional dancers called ranchos folkloricos. Ranchos Folkloricos is a traditional dance in Portuguese culture. In recent scholarship on Portuguese in the Ironbound, the dance was important in popularizing Portuguese culture in the city, while also maintaining their culture. Portuguese culture and identity not only contributed to community-building in the Ironbound, but also in preserving important monuments for the neighborhood such as Riverbank Park. While other ethnic groups in the Ironbound would have most likely contributed to celebrating the park’s reopening in some fashion, I believe that based on the evidence of Portuguese Sports Club being leaders of this dance, the photo shows Portuguese power in their community through their own institutions.

The emphasis of the photo is on the dancers based on the scale and the amount of space between the grass. As the focal points of the photo, the dancers draw the most attention, which demonstrates their relationship with the park.

Aside from the spatial contrasts, the difference in shading between the dancers and the grass is also interesting. The dancers are all in white, while the grass is mostly grey. There is also a shading contrast in the space below the center of the dancer’s stage; the far left and right are dark grey while the middle area has a lighter tone. This may also be a way of emphasizing the dancers as the focal point, however I believe that it also shows how the dance as a form of Portuguese culture is an important marker of the park.

While the photo was taken during the time of Riverbank Park’s grand reopening, the photo depicts it being empty aside from the Portuguese dancers. This could be because of how the photo was taken, but it also could be because the Portuguese Sports Club reserved the centerstage and a certain amount of time for their performance. The Newark Public Library’s Internet Archive contains photos of various performances that occurred in the Park, such as a Maypole dance, a fife and drum performance, and an act by students of the Wilson Avenue Elementary School. However, the dance by the Portuguese Sports Club is the only ethnic celebration shown, which demonstrates the power that they had as an Ironbound institution.

I believe that the spatial relationship and the positioning of the dancers not only highlights the purpose of the Park’s reopening but also furthers the overarching argument of the Portuguese through their culture and identity protected Riverbank Park as a central site in the Ironbound.

1997 photos:

Based on all three of the photos, I argue that they show that Portuguese were leaders and important contributors in SPARK’s fight to save the Park.

The sign above reads “Melhor, nao posso destruir nosso parque” (Fix, don’t destroy our park). As proven in past research, the Portuguese language was instrumental in organizing the Portuguese community in the Ironbound against Environmental issues. The ICC and the ICATW both relied on their Portuguese members as translators to people in their communities to get them involved in environmental issues.

On November 27, 1997, SPARK organized a candlelight vigil on Ferry Street in protest of Riverbank Park’s demolition for a new minor league baseball stadium. This took place after SPARK failed to achieve a public hearing on the issue at the Newark Municipal Court. Ferry Street is not only the central commercial district of the Ironbound with it’s numerous shops and restaurants, but also the heart of the Portuguese community in Newark. As seen in this photo, these people are Ferry Street residents. According to US census data on NJ and Newark, there were