From Pride to Prejudice: How Egyptian Politics Sculpted the World’s Largest “Garbage City”, 1940-1970s

by Arthanious Shafik

Site Description:

Mansheyet Nasser is a district of Cairo, Egypt. Cairo is one of the largest metropolises in the middle east. Known as the “Garbage City” and its people as the “garbage people” or “Zabbaleen”, it is largely a slum settlement whose economy is based upon recycling the tremendous trash produced throughout Egypt. “Zabbaleen” historically consists of indigenous Egyptians that are an ethnoreligious minority that faced heightened systemic persecution and discrimination which rose during the divisive rise of nationalism in Egypt’s post-colonial era. How did the once wealthy Egyptians with a rich history become Zabbaleen? And how does the rise of nationalism and the result of polar extremist ideologies exacerbate environmental and health disparities? What are the human right implications and how, if at all, have local and international law changed to address these issues during this time period? These answers will shed light on the dangerous consequences of extreme political nationalism in perpetuating systemic injustice wherever minority communities exist.

Introduction

Seven-year-old Marina returns from school on foot, shouldering her pink and white backpack. As she moves forward, pigeons fluttering overhead likely serve as inspiration for her mystical pigeon that she describes as a close imaginary friend. A rat scurries across the road, breaking Marina from her trance as she regains focus of her footing through the dirt roads. Marina has no lack of distracting visual stimuli – surrounded by families that line the streets. Outnumbering the people and competing for space in the streets, however, are myriad sacks of garbage piled high alongside every structure. As Marina passes her neighbor’s apartment complex, she witnesses a mother and three children sorting through syringes and other seemingly discarded medical supplies. Marina’s mother quickly greets her at the door and escorts her to the living room where a sack of unsorted garbage materials engulfs the floor. After an arduous day of learning at school and sorting paper at home, Marina clutches onto her ragged doll. Her mother uses a pair of old scissors to give the doll a haircut as Marina watches in ecstasy.[1]

These scenes from the 2008 documentary film, Marina of the Zabbaleen, provide a first-person walkthrough of Marina’s life. Marina is a typical child growing up in Mansheyiat Naser, an informal recycling community spanning 5.54 square kilometers (2.14 square miles) and home to thirty thousand men, women, and children.[2] These people are called the “Zabbaleen” (for plural, “Zabbal” for singular) and this derogatory term in Arabic translates to “Garbage People.” Despite its location within one of the world’s most densely populated cities – it is composed almost entirely of a small ethnoreligious minority group of Christians. Animals play a crucial role, not only in the imaginations of the inhabitants, but also the broader local ecosystem which is comprised of wild pigeons and rats as well as domesticated pigs, cows, and chickens among other livestock.[3] Marina’s family purchases unsorted paper materials in bulk for thirty cents a kilo (2.2lbs) and sells sorted stacks to recycling paper factories for forty cents a kilo. Lack of formal infrastructure increases safety concerns, from unplanned streets to lack of personal protective equipment for recyclers – even as they sift through potentially hazardous waste.

Why does Marina – like countless other children in her community – have to walk through piles of garbage to get home, sort garbage instead of doing homework, and then sleep with a rag doll? Why are the people in this ghetto mostly an indigenous and religious minority? How do the actions of the Egyptian government, or lack thereof, contribute to this subjugation? What efforts are taking place to improve life for the Zabbaleen? The answers to these questions require an intimate understanding of the community’s culture and history, as well as systemic forces that continue to shape it today.

News reporters, community activists, and researchers have begun to elucidate these unknowns with the growth of contemporary interest for this unique community. While the Egyptian government has historically restricted foreigners from visiting Mansheyiat Naser, this has not stopped committed individuals from reporting the story of these people.[4] Historians have documented the rise and fall of indigenous Christians in Egypt, and discussed how a history of adversity shapes the modern-day identities of these marginalized communities, like the Zabbaleen.[5] Social researchers have published journals detailing the beginnings of the Zabbaleen and their relationship with displacement.[6] News reporters have commented on events of social discrimination, and political persecution.[7] However, there is a need to discuss how the Coptic identity plays a role in the social, economic, and political marginalization of the Zabbaleen to identify the obstacles in the way of this community’s prosperity.

This paper will explore the interconnections of social, economic, and political persecution shaping a Coptic community centered around garbage. It achieves this purpose by first analyzing how the “Zabbaleen” transformed from scattered communities into their foothold in Mansheyiat Naser. It then discusses the broader history of Indigenous Christians in Egypt as it pertains to their transition into to a persecuted minority with certain advantages in the garbage recycling industry. Next, the social, economic, and political discrimination will be discussed. Finally, a discussion on contemporary activism and prospects of the Zabbaleen will take place.

From Scatter to Settlement: Rise of the “Zabbaleen” in Mansheiyat Nasser

Cairo’s unique infrastructure and demographics facilitated a long history of decentralized waste collection prior to the first appearances of modern-day “Zabbaleen.” Being historically among the most densely populated regions on the Earth, Cairo is dominated by large, multifamily complexes.[8] By the dawn of the twentieth century, the city’s population surpassed ten million residents.[9] For context, New York City’s population by 1900 was 3.4 million, and by 2020 reached only 8.8 million – all in an area 40% larger than Cairo.[10] The lack of a formal governmental waste collection service coupled with the rising population resulted in skyrocketing demand for waste collection services, which produced incentives for a grassroots solution. By the late nineteenth century, Arab migrants from the Dakhla Oasis forged deep interpersonal relationships with landlords and doormen for roughly 40% of Cairo’s residential structures. The people from the Dakhla Oasis, also known as the “Wahiya” (the Arabic word for “people of the oasis”) this group established a monopoly in the informal waste collection service by charging customers a collection fee and picking up waste from residents’ doorsteps. While the Wahiya ran their operation as one cohesive tribal organization, they consisted of several insular interspersed communities across the districts of Cairo. Such an organization was most efficient due to limited transportation technology.[11]

The Wahiya’s role in the establishment of the “Zabbaleen” was marked by a striking dichotomy: they were both early exploiters and simultaneously the only allies that helped the community. The “Zabbaleen” primarily consisted of rural farmers in the Upper Egypt region of Asyut who began to migrate to Cairo in the 1930s and 1940s in search of economic opportunity in response to a devastating famine. Asyut lies in a mountainous region of Egypt and is deeper into the African continent compared to Cairo. These factors make such a migration particularly arduous, considering that the people of Asyut had to leave their homes behind and carry their livestock with them. The lack of adequate transportation options coupled with the poverty of this population resulted in the majority of migrants being forced to make this trek on foot.[12]

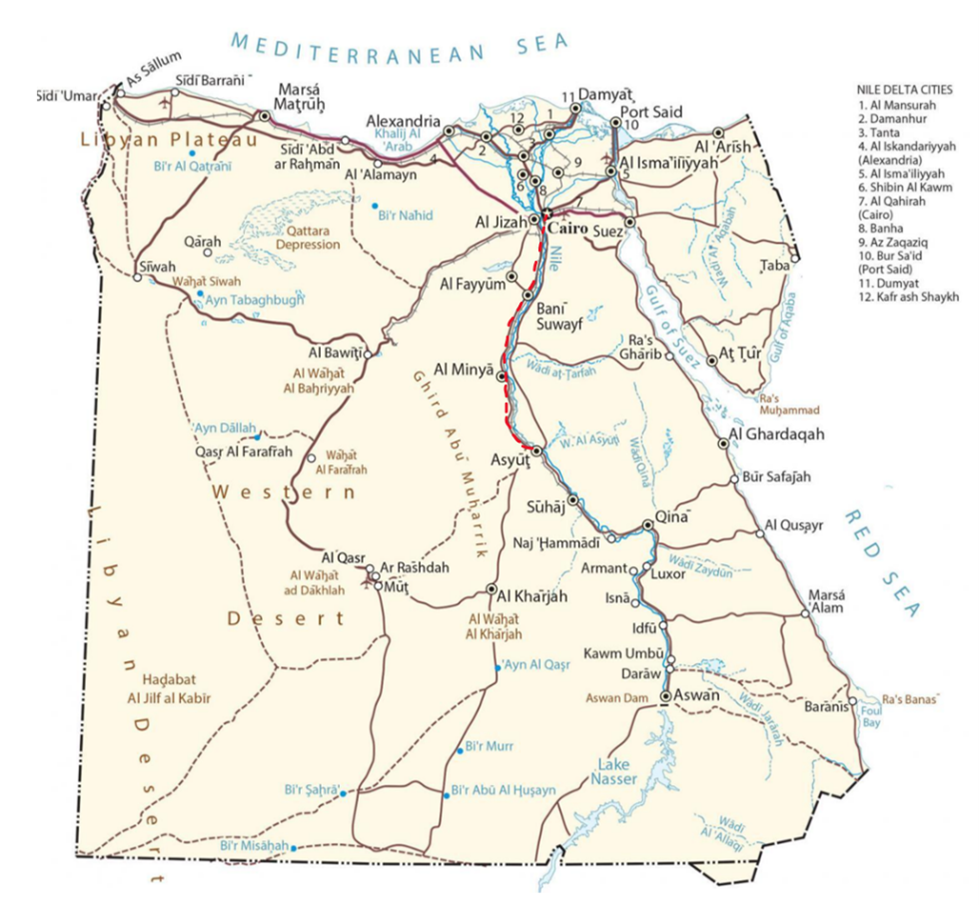

Detailed map of Egypt obtained from GIS-Geography maps.[13] Proposed migratory path from Asyut to Cairo traced in red dotted line by me.

The map provided by GIS-Geography provides perspective into the great challenges migrants faced, as the journey on foot from Asyut to Cairo, as shown by the dotted red line, exceeds two hundred miles.[14] The Zabbaleen initially found no success in employment, as they found themselves in the lowest caste of Egyptian society. In an interview with Adham, a local “Zabbal” and environmental activist, he describes how his community’s Christian and largely illiterate background meant that most businesses and government institutions refused to directly contract work with the community. The Wahiya then entered into an arrangement with these migrants; initially selling them organic waste which was used to feed animals. Eventually, the Wahiya began to allow these migrants to collect their own garbage to recycle by providing them with their established collection routes. The Wahiya gave no additional compensation, still pocketing the collection fees from various residents in the city despite totally outsourcing the collection process. The migrants had to develop large collection operations to make enough money to survive off of recycling. It is during this period when the growth of donkey carts became exponential, and larger dispersed communities of recyclers became colloquially known as “Zabbaleen.”[15]

Growth of the “Zabbaleen” community corresponded with a growth of persecution from the Egyptian government as they became increasingly intolerant. By the 1950s, several suburbs of Cairo began to enact legislation targeted at the Zabbaleen banning donkey carts from the roads. While Cairo had been industrializing, donkey carts remained a primary mode of transport for “Zabbaleen” who could not afford pickup trucks. Despite these laws, the Zabbaleen had become an integral part of waste collection and donkey carts failed to disappear.[16] According to Moussa, a local of Mansheyiat Nasser and environmental activist, tensions continued to rise until it finally reached a breaking point when a garbage collector’s donkey defecated in front of the home of Umm Kulthum. Moussa testified that Umm Kulthum, who was the most popular singer in the entire Middle East, was so irate her complaint landed at the desk of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser himself to remove the Zabbaleen from living in the area.[17] In 1969, the President would issue a decree establishing Mansheyiat Nasser, which is translated to “City of Nasser,” located on the outskirts of Cairo. He ordered the Zabbaleen to relocate to this area, effectively eliminating the many small garbage collecting settlements and creating a large, concentrated area for garbage collectors to live.[18]

In the face of adversity, the Zabbaleen continued to innovate and develop. What began as houses of tin shacks slowly turned into concrete, permanent homes in Mansheyiat Nasser.[19] Due to Islamic prohibition of contact with pigs, the Christian garbage collectors gained an effective monopoly on providing a source of local pork and more effective composting. The community continued to specialize from just garbage collection and composting to building their own factories where recycled materials are manufactured directly. Today, the community is home to hundreds of factories and represents the most efficient recycling operation in the world – with upwards of 85% of all collected waste being fully recycled.[20] The subjugation of the Zabbaleen under both the Wahiya and President Gamal Abdel Nasser serve as a microcosm of the millennia—old persecution of the Christians in Egypt along with their industrious perseverance.

From Pharaohs to Peasants: History of Copts in Egypt

Egypt is among the first places on Earth in which Christianity spread and experienced widespread adoption. While the term “Coptic” today is used to identify a sect of Christianity, the word directly translates to “Egyptian.” [21] Coptic is also the name of the native language of Egyptians since the 300 B.C. era.[22] According to tradition, Christianity began in Egypt when St. Mark established the faith in 49 A.D. Since then, the church in Egypt has had an unbroken line of one hundred and eighteen patriarchal successors.[23] Alexandria soon became one of the most important centers for Christianity, and the oldest historical record for the use of “pope” was attributed to the patriarch of Alexandria one hundred years before the earliest account of its use in Rome.[24] Today, Alexandria remains the only other patriarchal office of the early church besides Rome to use “pope” to address their patriarch. In addition to their influential role in early Christendom, the Christian faith served a crucial role in the cultural identity of early indigenous Egyptians. Vestiges of Pharaonic culture are found in the Coptic service, such as the hymn used to commemorate the burial of Jesus Christ, “Golgotha”, which uses the same musical tune that was used during the burial of the Pharaohs.[25] This rich history along with its strong ties to the native inhabitants of Egypt are explanations as to why simply the word “Coptic” today is interchangeable with the sect of Christianity in Egypt dominated by a minority indigenous African ethnicity.

The Arab invasion of Egypt began a long history of ethnic and religious persecution of Copts. This began a cycle of extreme adversity that threatened the survival of the Coptic identity, coupled with persistence and industriousness that would preserve these communities. The first instance of such adversity can be traced to the Arab conquest in 642 A.D. when general ‘Amr ibn al-‘As infamously presented the native Copts with three choices. Christians could either convert to Islam, die by the sword, or pay jizya (a heavy religious tax on non-Muslims). These policies began transforming Egypt into a majority Muslim and culturally Arab nation. Despite this, a sizeable Coptic minority persisted. This community consisted mainly of wealthy Christians who could afford to pay the jizya.[26]

The resilience of Christians would be tested again in the tenth century. The Islamic Caliph, Al-Muizz, often held theological discussions including Jewish and Christian representatives. During one of these proceedings, the Jewish representative, Yaqub (Jacob) Ibn Yusuf Ibn Killis, challenged the Coptic Pope Abraam, regarding a verse in the Bible that stated if one has faith as little a mustard seed, they could move a mountain. Al-Muizz demanded that Pope Abraam defend this teaching and ordered him to move the Mokattam mountain (located on the outskirts of Cairo) or face genocide. According to the Coptic History of the Patriarchs, Pope Abraam was directed by St. Mary in an apparition to seek out St. Simon, a poor one-eyed shoemaker. After a period of fasting for three days, St. Simon led a congregation chanting “Lord have mercy” near the mountain. After this, the mountain was thrusting up and down, and the sun could be seen from under it. Witnessing this miraculous event, Al-Muizz vacated his office and gave it to his son, then converted to Christianity. Since proselytizing any faith other than Islam was a capital crime, a baptismal font large enough for the immersion of a grown-up man had to be constructed in St. Mercurius Church. This font remains today with an Arabic inscription above reading “Maamoudiat Al-Sultan” which means the baptistry of the Sultan.[27]

Image of the Monastery of St. Samaan the Tanner, one of the largest present-day churches in the Mokattam mountain, with its amphitheater displayed. The church was carved directly out of the mountain and primarily built by and for the Zabbaleen in Mansheyiat Nasser. Image courtesy of the official website of Saint Samaan Church.[28]

The history of the Copts endurance under various regimes provides a foundational understanding of the resilience ingrained within the Zabbaleen. As descendants of these ancient Egyptians, the Zabbaleen have inherited not only the physical environment but also the legacy of perseverance against socio-economic marginalization. This lineage of persistence is crucial to comprehending their current struggles and their enduring spirit in the face of modern challenges. The transition from the religious and ethnic strife faced by their ancestors to the contemporary socio-economic and political issues highlights a continuous journey of survival and adaptation. Such historical insights are indispensable for a holistic understanding of the Zabbaleen’s identity, revealing how their past informs their present and motivates their ongoing fight for dignity and recognition within Arab-Egyptian society.

Merit and Margins: The Dichotomy of Social Prestige and the Recyclers’ Struggle

Egypt is composed of a hierarchical society that values traditional education and white-collar jobs which stigmatizes blue collar workers. This dynamic is expanded upon in Harry Pettit’s novel, The Labor of Hope: Meritocracy and Precarity in Egypt. He discusses how traditional communities place prestigious emphasis on individuals that become doctors, lawyers, and engineers despite the lack of substantial economic incentives these fields have over certain blue-collar jobs. Individuals who obtain these roles garnish respect not only from their families but even from systemic authority figures, such as increased leniency from police and permitting agencies.[29] Garbage collectors fall on the other end of this spectrum. In an interview, Adham reveals that the derogatory Arabic word used to reference his community colloquially as well as in the literature reflects this social stigmatization. Adham refuses to use the word “Zabbaleen” and states “We are not [garbage people]; we do not produce any garbage. We are environmentalists and recyclers.”[30] In an effort to push back against the predominate dehumanizing narrative, this paper will continue to exclusively use the term “recyclers” when referring to the “Zabbaleen” of Egypt.

Recyclers in Egypt typically have poor education and their simple lifestyle mired in poverty made them easy targets for abuse. In an interview, Moussa recalls several occasions being accosted by police when recycling and being forced to pay bribes for his safety. He also recalls an instance in which the police physically injured his donkey while it was carrying garbage to Mansheyiat Nasser, negatively impacting his future ability to recycle. This atmosphere of violence towards recyclers encourages inhumane treatment. Moussa recalls another instance in which a business littered trash bags on the side of the road, and when he attempted to retrieve it the owner verbally abused and threatened him to leave – believing it to be more fitting to leave his garbage on the streets than to hand it to recyclers.[31]

This treatment deprives recyclers of access to social services, perpetuating their poverty and hazardous living conditions. Despite being responsible for a significant portion of the cleanliness in Cairo, garbage is embedded in the living conditions of the recycling community. Many open spaces, whether adjacent to residential buildings or inside of them, are characterized by the cluttered and unsanitary appearance of garbage.

Two Zabbaleen men have their lunch at a rubbish storage area in the Mokattam neighborhood of Cairo.[32]

This photo depicts two male recyclers as they sit down for lunch surrounded by garbage being stored within feet of them. Taken by Fernando Moleres, a Barcelona-based photographer, he captures how this community lives in the suburb of Cairo known as Mansheyiat Nasser. As of 2011 when this photo was captured, the community has been collecting garbage throughout the metropolitan area for around seventy to eighty years as informal workers that their city has become dependent on for recycling. The lack of government recognition or support means that these Zabbaleen must make do with extremely few resources to eke out a living. This image shows the influence of systemic pressures in concentrating poverty and pollution on ethnoreligious minorities and the determination of these communities to persevere through the absence of formal infrastructure, beaten bodily appearance, and facial expressions.

The giant bulbous protruding sacks of garbage cause the men to appear ant-sized in comparison. Notably absent are industrial waste collection infrastructure – large metal garbage bins and waste storehouses that are protected from the elements. Acknowledging these limitations, the recyclers appear to fulfill their roles with a certain level of respect and care. These large plastic sacks are neatly tied and stacked – and the fact that these men feel comfortable eating so close to this garbage suggests trust in the level of care with its storage. Despite these great communal efforts, some trash will slip through the cracks, as shown by the litter on the floor that flanks the men on both sides. It is an expression that a community can only accomplish so much when it remains marginalized. The dirt streets symbolize another manner in which this community is neglected. The covered-up car indicates that there is a demand for motorized transportation in the community and that it is parked on what is considered a street, but there is no proper road infrastructure in place. This lack of proper facilities or government assistance means that much of the recyclers’ trash has to be stored in the streets or even in their homes. Being physically surrounded by waste with no refuge even during meals can have disastrous health consequences.

One possible example of this is the lump of skin seen protruding from the right cheek of the older man on the left, despite the camera being so far away. This mass could be indicative of little to no access to proper healthcare. The man on the right also carries a physical scar with half of his left middle finger being amputated. This demonstrates the duality of the dangerous nature of this work and the persistence in adversity, as the man has both his arm and pants sleeves rolled up; indicating he is working despite his injuries. These health conditions serve to exacerbate the state of poverty these men are captured to be in. The older man is eating just a meager meal with half a slice of pita bread. The clothes of the men are also dirty, tattered, and appear oversized. The man on the left is notably wearing two different sandals of opposite colors, which means that he might have only been able to afford to wear what he has found in the garbage. His staff also is haphazardly assembled with four wrappings of duct tape to keep it together. The table is full of scuffs and dark discoloration which alludes to the fact that it might also have been another man’s trash. The man on the right has both his arm and pant sleeves neatly rolled up, indicating discomfort with the heat and his clothing. The exposed left leg of the man on the right reveals what are either splotches of dirt or cuts and bruises. Either way, the discoloration of this man’s leg has not been attended to, likely due to a lack of access to healthcare.

Despite their horrendous conditions, these men do not appear to be hopeless or defeated. The man on the right takes an interest in the camera, staring straight at it while maintaining his composure. The other man looks off in front of him while sitting upright, seemingly uninterested. These postures exude a kind of self-made dignity. The photographer, who is a foreigner, would immediately stick out in the community. Despite their conditions, these men appear to make no effort to attempt to gain the photographer’s attention or ask for charity. While both men appear to be advanced in age, it is difficult to estimate the age of the man on the right, as the many wrinkles in his face contrast with his dark mustache and hair that has only begun to gray. This face appears to be battled hardened and worn through.

Systemic pressures like the lack of proper recycling and road infrastructure leave the recyclers disadvantaged in having to make their best use of communal resources at the expense of their environment’s cleanliness. The battered appearance of the men, including the makeshift cane in lieu of adequate medical devices, indicate the lack of healthcare or social programs which perpetuate a scene of extreme poverty among these minorities. Yet, the profoundness of this photo lies in the facial expressions of the two men. The dominating presence of both men exuding a sense of dignity and pride is evidence of a larger passion for perseverance despite the situation. Thus, the recyclers’ Coptic community stands as a quintessential example of resilience and resistance among hard-working, indigenous ethnoreligious minorities facing oppression through environmental pollution and poverty.

Economic Exclusion and Exploitation

The Egyptian government further subverts the recyclers’ ability to care for themselves and their community by implementing policies that undermine their ability to be compensated for their work. For instance, Law No.38 of 1967 General Public Cleaning constitutes official Egyptian legislation containing 12 articles on the management of solid waste. This document attacked the established informal sector of waste management as it prohibits the placement of solid wastes except in “designated areas.” It further outlines that garbage disposal services must be done by contractors licensed by the government while arbitrarily withholding licenses to the Coptic recyclers despite their current vital role in waste management. Since the establishment of this law in 1967, the government has not taken any executive function to enforce the flagrant violations by the recycling community, rather allowing them to continue to operate under the table. This shows how the government hypocritically refuses to recognize or work with the recyclers officially yet effectively permits their continued operation.[33]

In recent years, the government has begun to hire expensive multinational corporations (MNCs) to outsource garbage collection services. These corporations cost the government far more capital as they are equipped with advanced industrial garbage trucks. This means the government can only afford a small workforce that is ultimately less efficient than the established recycling community.[34] In an interview, Moussa notes that the distribution of federal funds towards MNCs as opposed to the local recyclers is a sore spot in his community and he feels that the government would rather eliminate their livelihoods than help develop their abilities. Even so, Moussa states that he does not currently feel threatened by the presence of MNCs and describes them more as a “decorative figure” than a functional solution.[35]

This kind of malicious behavior presents human rights implications. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), an international treaty in which Egypt is a signatory, Egypt likely violates multiple articles. First, by refusing to permit the Coptic recyclers, Egyptian policies are at odds with Article 21 Section 2 regarding equal access to public services. The recycling community primarily serves the lower- and middle-income neighborhoods in Cairo that have no other alternative for waste management services. Secondly, Article 23 Section 1 on the right to work as well as Section 3 regarding remuneration worthy of human dignity are two areas the Egyptian government actively undermine for the recycling community. By forcing their labor in the informal sector, the right to work as recyclers and demand fair compensation is infringed. Other policies openly attacked the recycling community’s ability to make a living such as banning donkey carts on certain roads without providing reasonable alternatives or assistance to the recyclers. Finally, Article 25 Section 1 describes the right to a standard of living to protect health.[36] The failure of the government to fund roads or social programs in Mansheyiat Nasser excessively burdens the community when compared to adjacent districts in Cairo.[37] In an interview, Moussa also states that there are a disproportionate amount of hazards in the recycling industry and workers are subjected to greater instances of injury or sickness. Despite this reality, Moussa recalls that there is often poor or nonexistent access to healthcare. He describes how the single local hospital is funded and run by the Church, but the medical professionals there are extremely limited and can only provide the most basic services. For other procedures or even to give birth at a hospital. Moussa states that the recyclers have to travel to government hospitals that charge exorbitant prices.[38]

Power Plays: Politics Against Egypt’s Recyclers

The recycling community’s lack of political representation have made them the target of various forms of systemic oppression. When Moussa and Adham were asked if the government could do anything to support their community, I was stunned when their answer was a resounding “no.” They went on to explain that there exists a fundamental distrust between the government and the recycling community, and they would rather be totally left alone than to ask for any type of help that would likely be shrouded in ulterior motives.[39] An example of this is when the government deemed the recycling settlement “unsafe” and ordered residents to vacate due to the presence of rocks and cliffs that could be unstable in the late 1990s. The government also failed to recognize any activists and appointed the local priest to mediate communication between the parties – further removing their contact with the recyclers. The government communicated that the cost to remove the hazardous rock formations in the Mokattam hill was too high at sixty million Egyptian pounds (approximately fifteen million USD)[40]. This presented the community with two options: to locally fund their own removal of the stones or vacate the area. Rather than give up, the community relied on charitable contributions and volunteer work to complete the total renovation around the Mokattam mountain by 2011. In the end, the recyclers were able to do this work for only three million Egyptian pounds (approximately seven hundred and fifty thousand USD)[41]. Until this day, the ability for the community to accomplish this task at five percent the cost quoted by authorities is considered a second miracle at the Mokattam site by the recyclers.[42]

Moussa distrusts the official narratives of authorities as to why the recyclers had to suddenly vacate or clear the rock debris at an insurmountable cost. He notes that it was well known the area of Mansheyiat Nasser was previously an abandoned quarry mine that was used during the age of the Pharaohs as a source of rock for the pyramids. Therefore, the government knew this land was littered with debris when it founded the district and forced the migration of recyclers. Moussa argues it is no coincidence that the government decades later when the population of Cairo begins to increase exponentially now presents this issue. Moussa speculates that the increasing population increased the value of this land that was once undesirable, and the government coveted the area.[43]

A more unsubstantiated instance of political persecution occurred in 2011 when the government ordered the culling of recycler’s pigs to combat the spread of H1N1. A New York Times article by Slackman describes the fallout of such a decision. Slackman visits Cairo where he interviews government officials, an economist, and the leader of a grassroots advocacy organization for the recyclers. Slackman also provides context regarding the initial pushback to the executive order to cull the pigs and how the community is trying to recover with no government assistance.

Local recyclers cull pig herds due to a government decree. Image courtesy of NBC news.[44]

Some might argue that the executive order to cull the pigs, while retrospectively a mistake, was made to slow the spread of H1N1 and was therefore not a direct prejudice against the Coptic community. This rationalization cannot stand, because Slackman documents “health officials worldwide said that the virus was not being passed by pigs” yet the government’s response was to double down, now arguing they wish to clean the “zabaleen’s crowded, filthy, neighborhood.” Copts have a monopoly on the pig farming and composting sector because Muslims believe that pigs are unclean. Therefore, when the government argues that the pigs must be killed because they are filthy, the discussion no longer is about H1N1, but how Islamic beliefs must be imposed on a subjugated Christian community. This evident form of political persecution further damages Egypt’s economic outlook.

Galal Amin, an economist, hypothesized that this action was a result of a “weak government that is anxious to please somebody.” His analysis of the Egyptian government as “weak” is significant, as it exposes a lack of confidence in the state’s ability to navigate crisis. Amin affirms that his experience with Cairo becoming overwhelmed with trash piling in the streets is a serious issue, acknowledging both the damage to the recyclers and the larger surrounding Cairo community. The pessimistic diction used by Amin showcases how distrust in the Egyptian government due to discriminatory policies raises economic concerns.

The testimonies of Amin also depict an environmental disaster unfolding in Cairo due to the buildup of uncollected trash. This is corroborated by the testimony of Moussa Rateb, a former garbage collector, when he said, “Everything used to go to the pigs, now there are no pigs, so it goes to the administration.” Rateb clearly assigns blame to the discriminatory order by the government administration to cull the pigs as the reason for the increase in pollution, citing the pigs’ vital role in establishing environmental sustainability. The testimonies of global health officials, Galal Amin, and Moussa Rateb depict systemic religious persecution, lowered economic confidence, and increased environmental pollution.[45]

Voices Rising: Activism Amplifying Recyclers’ Impact

Grassroot environmental activists have worked to spread awareness of the recycling community to increase international opportunities that allow the recyclers to dampen the effects of local persecution. One such activist is Moussa, who taught himself English in order to spread awareness by giving tours of the recycling community to foreigners. His knowledge of the hundreds of operations that go into recycling all different kinds of materials in an economically viable manner with little waste have captivated many visitors to Cairo. Moussa states that he captured the attention of a large international company, Nestle, which pays him a monthly salary to report on the volume of Nestle containers that become recycled in his community. Through this combination of working with Nestle and offering guided tours, Moussa has shifted from garbage collection and is able to more meaningful support his wife and three young daughters.

Adham, a friend of Moussa with similar origins, is also involved in activism. Having also taught himself English, he was one of the main stars in a famous documentary called Garbage Dreams which exposes the reality and day to day of recyclers. Since this film, Moussa has been invited by various organizations and has traveled across the globe to spread information on recycling logistics and the plight of recyclers in Egypt. Both Moussa and Adham are passionate about environmentalism on a global scale and believe that the accomplishments of the recyclers in Mansheyiat Nasser could be adapted worldwide to improve recycling efficiencies.[46]

Conclusion

Marina’s story is a type of archetype through which the challenges recyclers face can be understood. The lack of roads and surrounding sacks of garbage on the streets Marina sees on her walk home is the cause and consequence of social isolation from larger Egyptian society. The fact that she walks home alone and upon arrival must dedicate time to helping her mother work is the typical result of economic exclusion and subjugation in the informal sector of the economy. The crowded family homes and streets represent the impact of political decisions that are made without the recyclers’ interests taken into consideration, such as the forced migration of all recycling operations to a single undeveloped district on the outskirts of Cairo. At the same time, Marina’s dreams to be a doctor and her mother’s ability to entertain Marina by cutting the hair of her ragdoll represent the resilience, ingenuity, and hope in the community. Since Marina walked the crowded streets of Mansheyiat Nasser as a young girl in 2008, the population has ballooned from thirty thousand to two hundred and fifty thousand in 2017, a testament of the recycler’s ability to persevere in the face of adversity.[47]

Perseverance is a virtue ingrained in the identity of Coptic Christians throughout Egypt through their rich cultural and religious history. Their marginalized identity is also a contributing factor that keeps them from climbing the social ladder and stuck in less prestigious occupations that continue to make them social pariahs. Recyclers also face further systemic economic exploitation that keeps them in the dangerous informal sector of the economy and potentially violates human rights. Their community is also subjected to irrational political persecution as seen in the order to cull the pigs which caused a devastating garbage buildup across Cairo.

The recycling community today continues to invest in a better future for the recycling industry and their children. Several schools linked to charitable organizations provide education for the children in the community with a focus on breaking the cycle of illiteracy in the community. One such school is Marina’s, which continues to serve children in the community today.[48] Community activists are engaged in spreading awareness of their society and are dedicated on a global scale to improve environmental conditions through more effective recycling strategies.

While Mansheyiat Nasser is on a positive development track, several changes still must be implemented in order to break the cycle of persecution. I believe that the government must spread awareness throughout the nation on the work of the recyclers and publicize their impressive efficiency and industriousness to break the social stigma with recyclers. Formal recognition and permits to recycle must be granted to the community and acknowledgement of their service and strategies to improve and replicate their work across the nation should be discussed. Finally, the government should permit the formation of local grassroot organizations and activists and appoint local community members to ministerial environmental boards to provide the community with an adequate political voice. None of these changes are pragmatic without increased inclusivity toward indigenous Egyptian cultural practices and Christian faith.

[1] Wassef, Engi, dir. Marina of the Zabbaleen. 2008; Cairo: Blue Nile Productions. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1235826/.

[2] Geographical area statistic derived from: Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS). 2017. “2017 Census for Population and Housing Conditions.” CEDEJ-CAPMAS. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.cedejcapmas.org/adws/app/4d5b52dc-669d-11e9-b6a6-975656a88994/index.html. Population statistic found in the prelude portion of the film,

[3] Soth, Amelia. “Cairo’s Zabbaleen and Secret Life of Trash.” JSTOR Daily, November 30, 2022. https://daily.jstor.org/cairos-zabbaleen-and-secret-life-of-trash/.

[4] Based off of Engi Wassef’s narration on being told she is not allowed to film the recycling settlement by Egyptian officials, Wassef, Engi, dir. Marina of the Zabbaleen. 2008; Cairo: Blue Nile Productions. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1235826/.

[5] Gregorius, Bishop. “Christianity, the Coptic Religion and Ethnic Minorities in Egypt.” GeoJournal 6, no. 1 (1982): 57–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41143000.

[6] Assaad, Ragui. 1996. “Formalizing the Informal? The Transformation of Cairo’s Refuse Collection System.” Journal of Planning Education & Research 16: 118.

[7] Slackman, Michael. 2009. “Cairo’s Poor Spark Environmental and Health Dangers.” The New York Times, September 19. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/20/world/africa/20cairo.html.

[8] Anna Rowell. “Beyond the Bounds of the State: Reinterpreting Cairo’s Infrastructures of Mobility.” Middle East – Topics & Arguments 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.17192/meta.2018.10.7589.

[9] O’Neill, Aaron. “Population of Egypt 1800-2020.” Statista, February 2, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1066887/total-population-egypt-historical/.

[10]For the population statistic, see: U.S. Census Bureau, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, Vol. 6, Families (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1930), Table 4.

[11] R. Assaad, “Formalizing the Informal? The Transformation of Cairo’s Refuse Collection System,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 16, no. 2 (1996): 115-126, https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9601600204.

[12] Fahmi, Wael, and Keith Sutton. 2010. “Cairo’s Contested Garbage: Sustainable Solid Waste Management and the Zabbaleen’s Right to the City.” Sustainability 2: 1769.

[13] GISGeography. “Egypt Map – Cities and Roads,” April 27, 2024. https://gisgeography.com/egypt-map/#Satellite-Map.

[14] Google Maps. “Directions for Walking from Asyut, Egypt to Cairo, Egypt.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://maps.app.goo.gl/UzeegH7qE9QWa5j3A.

[15] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[16] Yahia, Shawkat. “Cairo’s Ultimate Smart Vehicle: The Donkey Cart – Worldcrunch.” World Crunch, November 13, 2015. https://www.madamasr.com/sections/environment/donkey-cart-journal.

[17] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[18] “Cairo360 Staff.” 2017. “In Photos: The Stunning Serenity of St. Samaan Church.” Cairo360, April 6. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.cairo360.com/article/sights-travel/in-photos-the-stunning-serenity-of-st-samaan-church/#:~:text=The%20area%20of%20Mansheyet%20Nasser%2C%20or%20Zabaleen%2C%20was,the%20foot%20of%20Mokattam%20Hills%20by%20a%20decree.

[19] Assad, R. 1998. “Upgrading the Mokattam Zabbaleen (Garbage Collectors) Settlement in Cairo: What Have We Learned?” Paper presented at the MacArthur Consortium on International Peace and Cooperation Symposium on The Challenge of Urban Sustainability. Accessed April 28, 2024. http://www.socsci.umn.edu/~bongman/urbansustainability/assad.htm.

[20] Knowledge at Wharton Staff. “Waste Not: Egypt’s ‘Garbage People’ Seek Formal Recognition.” Knowledge at Wharton (blog), August 10, 2010. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/waste-not-egypts-garbage-people-seek-formal-recognition/.

[21] Gregorius, Bishop. “Christianity, the Coptic Religion and Ethnic Minorities in Egypt.” GeoJournal 6, no. 1 (1982): 57–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41143000.

[22] Auth, Susan. “Myth and Gospel: Art of Coptic Egypt.” African Arts 11, no. 3 (1978): 82–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/3335421.

[23] “Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria.” Last modified 2012. “All Popes.” Accessed April 28, 2024. https://copticorthodox.church/en/coptic-church/all-popes/.

[24] Letter from the Bishop of Rome addressing the Alexandrian Patriarch as “pope” can be found here: Eusebius of Caesarea. “Historia Ecclesiastica,” Book VII, Chapter 7.7. Translated by Kirsopp Lake, J.E.L. Oulton, and H.J. Lawlor. In The Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 1-2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926-1932. Accessed April 28, 2024. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg2018.tlg002.perseus-grc1:7.7.

The earliest instance of the use of “pope” for the Roman patriarch can be found here: Cross, F. L., and E. A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL3436987M/The_Oxford_dictionary_of_the_Christian_Church.

[25] “CopticCast.” 2020. “‘Golgotha’ Coptic Orthodox Hymn.” CopticCast, October 1. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://copticcast.com/watch/golgotha-coptic-english-arabic-to-coptic-lyrics-m4v_TQqTgbERWIEBMM9.html#:~:text=%27Golgotha%27%20is%20a%20Coptic%20Orthodox%20hymn%20that%20is,and%20funeral%20ceremonies%20and%20added%20Christian%20words%20instead%21.

[26] Armanios, Febe. “Approaches to Coptic History after 641.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 3 (2010): 483–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40784827.

[27] “Coptic Orthodox Church Network.” n.d. “Saint Simon the Tanner.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.copticchurch.net/synaxarium/saints/simon-popeabraam.html.

[28] “Saint Samaan Church.” n.d. “Photo Gallery.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.samaanchurch.com/en/photo-gallery.

[29] Pettit, Harry. The labor of hope meritocracy and precarity in Egypt. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2024.

[30] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[31] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[32] Moleres, Fernando. 2011. Zabbaleen Men Have Their Lunch at a Rubbish Storage Area in the Mokattam Neighbourhood of Cairo. The Zabbaleen are a minority Coptic religious community who have served as Cairo’s informal rubbish collectors for the past 70 to 80 years. They recycle 80% of the waste they collect. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://library-artstor-org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/asset/APANOSIG_10313572917.

[33] Law No. 152 of 2015 Regulating Waste Management.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/egy152515.pdf. Can be found in the Document archive of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAOLEX Number LEX-FAOC152515).

[34] Fahmi, Wael, and Keith Sutton. “Cairo’s Zabbaleen Garbage Recyclers: Multinationals’ Takeover and State Relocation Plans.” Habitat International 30 (2006): 809-837. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0197397505000494.

[35] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[36] United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted by the General Assembly on 10 December 1948. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[37] Reuters. 2021. “Egypt Forges New Plan to Restore Cairo’s Historic Heart.” September 29. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/egypt-forges-new-plan-restore-cairos-historic-heart-2021-09-29/.

[38] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[39] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[40] Historical exchange rates from 1953 with graph and charts (fxtop.com)

[41] Historical exchange rates from 1953 with graph and charts (fxtop.com)

[42] Documentary produced by the head priest of St. Simon the Tanner Monastery: Ibrahim, Samaan. “Rocks of Faith.” YouTube video, 23:34. May 16, 2011. https://youtu.be/JMUGNGuLpsk.

[43] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[44] Nouri, Nasser. “Groups Blast Egypt for Killing Pigs in Flu Scare.” NBCNews.com, May 18, 2009. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna30813227.

[45] Slackman, Michael. 2009. “Egypt’s Rich Remake Cairo; The Poor Are Pushed to the Desert.” The New York Times, September 20. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/20/world/africa/20cairo.html.

[46] Shafik, Arthanious. “Cairo Recycling City Interview.” Interview with Moussa and Adham. YouTube video, 49:25. April 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IPOFqkOU-UU.

[47] Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). 2017. “2017 Census for Population and Housing Conditions.” CEDEJ-CAPMAS. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://www.cedejcapmas.org/adws/app/4d5b52dc-669d-11e9-b6a6-975656a88994/index.html.

[48] In Cairo’s Trash City, School Teaches Reading, Recycling February 16, 2010. Anonymous NewsHour Productions, 2010. https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/in-cairo-s-trash-city-school-teaches-reading-recycling-february-16-2010.

Primary Sources:

Title: “Belatedly, Egypt Spots Flaws in Wiping Out Pigs” published by The New York Times (NYT) on 09/19/2009, written by Michael Slackman.

Location: NYT – Africa Articles. Interviews based in Cairo, Egypt.

Description: Containing interviews from Egyptian government officials, advisors, and local Zabaleen, this piece demonstrates how discriminatory policies caused environmental catastrophe with bleak hope for change. When trash piles up in Cairo following the order to cull the pigs of the Zabaleen, the government finally admits to negligence. Community leaders of the Zabaleen voice their frustration with the government continuing to ignore their critical recycling role and refusing to offer any assistance.

Title: Marina of the Zabbaleen, Documentary Film by Engi Wassef and Blue Nile Productions (2009)

*Non-narrative video shows first-person perspective and lived experiences of Marina

Location: Available for purchase (DVD) at: https://www.orthodoxbookstore.org/products/marina-of-the-zabbaleen. IMDB page: https://m.imdb.com/title/tt1057535/.

Description: This documentary focuses on the story of a 7-year-old girl who lives in the Zabaleen community, and her family consisting of her brother and parents. The silent (non-narrative) aspects of the film candidly follow the life of this child. Through these clips, one explores the inequality and horrid conditions this family faces and how they remain hopeful through faith and persistence. It also discusses the increased risk of disease Zabaleen faces due to their living conditions.

Title: Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UHDR) – ratified by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948

Location: United Nations online archive of resolutions.

Description: This document, signed by Egypt, expresses fundamental human rights as they pertain to international law. By refusing to recognize the recycling sector of the Zabaleen, Egyptian policies are at odds with Article 21 Section 2 regarding equal access to public services, Article 23 Section 1 on the right to work as well as Section 3 regarding remuneration worthy of human dignity, and Article 25 Section 1 regarding the right to a standard of living to protect health. This will be contrasted with first-hand accounts and image evidence showing the Zabaleen living in squalor and at disproportionate risk of life-threatening diseases.

Title: Law No.38 of 1967 General Public Cleaning. (Official Egyptian Legislation containing 12 articles on the management of solid waste)

Link: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/egy152515.pdf.

Location: Document archive of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAOLEX Number LEX-FAOC152515)

Description: This government document attacks the informal sector of waste management that began to rise in Cairo in the 1940s with the development of the Zabaleen. It prohibits the placement of solid wastes except in designated areas. It outlines that garbage disposal services must be done by contractors licensed by the government, among other provisions that conflict with the Zabaleen way of life. Since the establishment of this law in 1967, the government has not taken any executive function to enforce the flagrant violations by the Zabaleen community, rather allowing them to continue to operate under the table. This shows how the government hypocritically refuses to recognize or work with the Zabaleen officially but effectively allows their continued operation.

Title: Rocks of Faith, a video interview by Saint Saaman the Tanner Monastery of the Garbage Collectors Area, published on May 16, 2011.

Link: https://youtu.be/JMUGNGuLpsk?si=X7aiqIzRuG4zAQSu.

Location: YouTube channel of Father Samaan Ibrahim.

Description: Father Samaan, the official local Coptic priest of the Zabaleen provides his insight on the early establishment of his community. He describes his congregation’s poverty and conflict in their relationship with the government. He also explains his role as an official advocate and mediator on behalf of all the Zabaleen with the Egyptian government as they attempted to disperse the community. This highlights the adversarial relationship with larger society and government as well as the persistence of the community. The plight of the Zabaleen embodies that of Copts at large since the Arab conquest of Egypt; an uphill battle.

Primary Source Analysis

“Belatedly, Egypt Spots Flaws in Wiping Out Pigs”

This New York Times article explores the fallout of an executive order by the Egyptian government to cull the pigs of the Zabaleen following the H1N1 scare. Slackman visits Cairo where he interviews government officials, an economist, and the leader of a grassroots advocacy organization for the Zabaleen. Slackman also provides context regarding the initial pushback to the executive order to cull the pigs of the Zabaleen and how the community is trying to recover with no government assistance. My analysis of this article is that the government actively persecutes Copts, this persecution raises doubts about the Egyptian economy, and this persecution increases environmental pollution.

Some might argue that the executive order to cull the pigs of the Zabaleen, while retrospectively a mistake, was made in an attempt to slow the spread of H1N1 and was therefore not a direct prejudice against the Coptic community. This rationalization cannot stand, because Slackman documents “… health officials worldwide said that the virus was not being passed by pigs…” yet the government’s response was to double down, now arguing they wish to clean the “… zabaleen’s crowded, filthy, neighborhood”. Copts have a monopoly on the pig farming and composting sector because Muslims believe that pigs are unclean. Therefore, when the government argues that the pigs must be killed because they are filthy, the discussion no longer is about H1N1, but how Islamic beliefs must be imposed on a subjugated Christian community. This evident form of political persecution further damages Egypt’s economic outlook.

Galal Amin, an economist, hypothesized that this action was a result of a “… weak government that is anxious to please somebody”. His analysis of the Egyptian government as “weak” is significant, as it exposes a lack of confidence in the state’s ability to navigate crisis. Amin affirms that his experience with Cairo becoming overwhelmed with trash piling in the streets is a serious issue, acknowledging both the damage to the Zabaleen and the larger surrounding Cairo community. The pessimistic diction used by Amin showcases how distrust in the Egyptian government due to discriminatory policies raises economic concerns.

The testimonies of Amin also depict an environmental disaster unfolding in Cairo due to the buildup of uncollected trash. This is corroborated by the testimony of Moussa Rateb, a former garbage collector, when he said “Everything used to go to the pigs, now there are no pigs, so it goes to the administration”. Moussa clearly assigns blame to the discriminatory order by the government administration to cull the pigs as the reason for the increase in pollution, citing the pigs vital role in establishing environmental sustainability. The testimonies of global health officials, Galal Amin, and Moussa Rateb depict systemic religious persecution, lowered economic confidence, and increased environmental pollution.

Secondary Sources:

Fahmi, Wael, and Keith Sutton. “Cairo’s Contested Garbage: Sustainable Solid Waste Management and the Zabaleen’s Right to the City.” Sustainability 2, no. 6 (June 2010): 1765–83. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2061765.

This paper navigates the convoluted political environment of Cairo’s garbage city, detailing efforts by the government to deal with public waste. While the city remains a model for being among the greenest recycling operations globally, the government has shied away from providing any official support and has taken steps which the local populous report undercut their livelihood. Instead of investing in operations which are already existing in order to improve quality of life and efficiency, the government has provided funds to several multinational corporations to engage in recycling efforts. While their impact remains relatively small, the people see this as the government slowly trying to decimate their jobs and ultimately drive the Copts from the city.

Soth, Amelia. “Cairo’s Zabbaleen and Secret Life of Trash.” JSTOR Daily, November 30, 2022. https://daily.jstor.org/cairos-zabbaleen-and-secret-life-of-trash/.

This article exposes social and environmental aspects of the Zabbaleen’s work, as well as the similarities and differences between them and other individual recyclers around the world. It gives insight not only to the dramatic living conditions but also to the scale of the environmental challenge posed in this specific area of Egypt compared to anywhere else in the world. The unique situation of the Zabbaleen as outlined in this article might be open to special humanitarian and universal law considerations. Further, it sheds light on how the government has historically approached the Zabbaleen with hostility and threatened their livelihood and identity.

Pruitt, Jennifer. “The Miracle of Muqattam: Moving a Mountain to Build a Church in Fatimid Egypt,” 277–90, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004280229_017.

This paper discusses the rich history of Coptic heritage in Manshiyat Naser, specifically it being the location of a dramatic miracle that occurred in the middle ages. According to tradition, the Islamic Caliph ruling over Egypt gave Pope Abraham an ultimatum: to prove the Bible verse that faith as a mustard seed would move a mountain or face persecution in 3 days. In a public event, Mokattam mountain, which is in Manshiyat Naser, was moved miraculously. The caliph resigned from his post and quietly converted to Christianity, living the rest of his life in self-imposed exile in a monastery. The Coptic people commemorate this miracle annually and its story remains a relevant factor in understanding the tense relationship between Copts in Egypt and the governing authorities. The paper further describes how a massive church was built here in the 1970s as the Coptic community of Manshiyat Naser began to grow exponentially.

Knowledge at Wharton. “Waste Not: Egypt’s ‘Garbage People’ Seek Formal Recognition.” Accessed February 18, 2024. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/waste-not-egypts-garbage-people-seek-formal-recognition/.

This article discusses how lack of official government recognition is hurting the ability of the Zabbaleen to grow economically. The government’s total lack of economic support shows by the fact that over 90% of investment comes from NGOs. The people of Manshiyat Naser remain discriminated against even in occupations that deal with garbage recycling.

Slackman, Michael. “Belatedly, Egypt Spots Flaws in Wiping Out Pigs – The New York Times.” The New York Times, September 19, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/20/world/africa/20cairo.html.

This article describes the detrimental effects on the Christian community after the government hastily decided to kill all pigs. Masked under concern of the spreading H1N1 virus, the Egyptian government decided that they would kill all pigs owned in Christian communities. Officially, laws also exist banning the growing of pigs for food. The pigs served as an essential part of Cairo’s recycling infrastructure and a source of food for the Christian recyclers. This not only devastated the recycling community, but also led to buildups of trash throughout Cairo.

Image Analysis:

Fernando Moleres. 2011. “Zabbaleen men have their lunch at a rubbish storage area in the Mokattam neighbourhood of Cairo.” The Zabbaleen are a minority Coptic religious community who have served as Cairo’s informal rubbish collectors for the past 70 to 80 years. They recycle 80% of the waste they collect. https://library-artstor-org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/asset/APANOSIG_10313572917.

This photo depicts two male garbage collectors (known as Zabaleen) as they sit down for lunch surrounded by garbage being stored within feet of them. Taken by Fernando Moleres, a Barcelona-based photographer, he captures how this Christian indigenous ethnoreligious community lives in the suburb of Cairo known as Manshiyat Nasser. As of 2011 when this photo was captured, the community has been collecting garbage throughout the metropolitan area for around seventy to eighty years as informal workers that their city has become dependent on for recycling. The lack of government recognition or support means that these Zabaleen have to make do with extremely few resources to eke out a living. The absence of formal infrastructure, This image shows the influence of systemic pressures in concentrating poverty and pollution on ethnoreligious minorities and the determination of these communities to persevere through the absence of formal infrastructure, beaten bodily appearance, and facial expressions.

The giant bulbous protruding sacks of garbage cause the men to appear ant-sized in comparison. Notably absent are industrial waste collection infrastructure – large metal garbage bins and waste storehouses that are protected from the elements. Acknowledging these limitations, the Zabaleen appear to fulfill their roles with a certain level of respect and care. These large plastic sacks are neatly tied and stacked – and the fact that these men feel comfortable eating so close to this garbage suggests trust in the level of care with its storage. Despite these great communal efforts, some trash will slip through the cracks, as shown by the litter on the floor that flanks the men on both sides. It is an expression that a community can only accomplish so much when it remains marginalized. The dirt streets symbolize another manner in which this community is neglected. The covered-up car indicates that there is a demand for motorized transportation in the community and that it is parked on what is considered a street, but there is no proper road infrastructure in place. This lack of proper facilities or government assistance means that much of the Zabaleen’s trash has to be stored in the streets or even in their homes. Being physically surrounded by waste with no refuge even during meals can have disastrous health consequences.

One possible example of this is the lump of skin seen protruding from the right cheek of the older man on the left, despite the camera being so far away. This mass could be indicative of little to no access to proper healthcare. The man on the right also carries a physical scar with half of his left middle finger being amputated. This demonstrates the duality of the dangerous nature of this work and the persistence in adversity, as the man has both his arm and pants sleeves rolled up; indicating he is working despite his injuries. These health conditions serve to exacerbate the state of poverty these men are captured to be in. The older man is eating just a meager meal with half a slice of pita bread. The clothes of the men are also dirty, tattered, and appear oversized. The man on the left is notably wearing two different sandals of opposite colors, which means that he might have only been able to afford to wear what he has found in the garbage. His staff also is haphazardly assembled with four wrappings of duck tape to keep it together. The table is full of scuffs and dark discoloration which alludes to the fact that it might also have been another man’s trash. The man on the right has both his arm and pant sleeves neatly rolled up, indicating discomfort with the heat and his clothing. The exposed left leg of the man on the right reveals what are either splotches of dirt or cuts and bruises. Either way, the discoloration of this man’s leg has not been attended to, likely due to a lack of access to healthcare.

Despite their horrendous conditions, these men do not appear to be hopeless or defeated. The man on the right takes an interest in the camera, staring straight at it while maintaining his composure. The other man looks off in front of him while sitting upright, seemingly uninterested. These postures exude a kind of self-made dignity. The photographer, who is a foreigner, would immediately stick out in the community. Despite their conditions, these men appear to make no effort to attempt to gain the photographer’s attention or ask for charity. While both men appear to be advanced in age, it is difficult to estimate the age of the man on the right, as the many wrinkles in his face contrast with his dark mustache and hair that has only begun to gray. This face appears to be battled hardened and worn through.

Systemic pressures like the lack of proper recycling and road infrastructure leave the Zabaleen disadvantaged in having to make their best use of communal resources at the expense of their environment’s cleanliness. The battered appearance of the men, including the makeshift cane in lieu of adequate medical devices, indicate the lack of healthcare or social programs which perpetuate a scene of extreme poverty among these minorities. Yet, the profoundness of this photo lies in the facial expressions of the two men. The dominating presence of both men exuding a sense of dignity and pride is evidence of a larger passion for perseverance despite the situation. Thus the Zabaleen’s Coptic community stands as a quintessential example of resilience and resistance among hard-working, indigenous ethnoreligious minorities facing oppression through environmental pollution and poverty.

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews:

The oral interview is presented as a video for this project.