E Pluribus Unum: How A Small New Jersey Suburb Received One of The Most Complicated Cleanups in EPA History (1979-2021)

by Gabe M. Weir

Site Description:

In the 1920s, on the border of Glen Ridge and Orange, NJ, the US Radium Company operated a factory where radium paint was applied to clock dials. Radium byproducts made their way into the soil surrounding the factory, which was then used to fill in the ground, as well as in cement for foundations and sidewalks. This radioactive refuse covered 130 acres, which today is mostly residential properties and a public park. In the 1980s, the state identified dangerous amounts of radon gas in homes, and excessive amounts of gamma radiation both inside and outside. The EPA established the area (along with its sister site in Montclair/West Orange) a superfund site, and cleanup went on from 1990 to 2004. Firstly, why was this radium-enriched soil used for anything? The case of the “Radium Girls” had already faced trial and shown the public the deadly effects that radium exposure can have on the human body. Why was this not acknowledged as dangerous, and does land value represent a possible culpability and acknowledgement of danger? How did this problem get recognized in the 1980s and what were health concerns from it that people in the area were exposed to? The US Radium Company was not the only clock face painter in the United States, and not the only one to run into legal trouble over girls at the factories becoming ill. Likely there are more situations where dangerous levels of radium made their way into soil in areas that could harm people; how did other sites differ and how might have the two sites on the borders of wealthier (white) communities received different treatment?

A house with a particularly high concentration has its foundation replaced

Introduction:

Glen Ridge is a small suburban town in northern New Jersey. It is markedly unique for a few reasons. For example, the town is known for its signature green gas lamps, of which it contains almost a quarter of functioning ones in the entire United States. In terms of square mileage, the town is smaller than New York City’s Central Park. The town has a 5K race and a street dedicated to longtime resident Horace Ashenfelter, a 1952 Olympic gold medalist in track and field and although he went to Montclair High School, astronaut Buzz Aldrin was born there. Tom Cruise (or Mapother, prior to stardom) was a member of the high school’s wrestling team in the early 80s, and Ezra Koenig, frontman of the band Vampire Weekend is remembered as the drum major of the school’s marching band. There is something else that is unique about Glen Ridge, something that most people living in town were not aware of until the EPA stepped in to address it: until 2004, a 55 acre site contained almost six million cubic feet of radioactive soil that had been transported there back in the 1920s.

Before we as a society knew about the health risks involved with radiation, no oversight or guidance of any sort existed. When companies, such as United States Radium Corporation, located a few blocks over in Orange, New Jersey, dealt with their radium, it was mismanaged to levels that would be horrifying to experience as a present day onlooker. The United States Radium Corporation processed raw radium ore from metal to a powder, which created a lot of byproducts in the form of rock and dirt. This byproduct was treated as landfill, and was transported from the factory in Orange to Glen Ridge, where it was used to terraform a residential neighborhood in planning and mixed into concrete foundations for a few houses. The radioactivity was not even noticed until 1979 and was not fully cleaned up for another 25 years.

What makes Glen Ridge’s cleanup unique is that Glen Ridge received an extensive and complex $150 million full remediation ($250-336M in 2021). The job was preformed so thoroughly that the EPA has removed the site from its site list does not even monitor it any more. This was not the original plan, however, as the EPA originally set forth a partial remediation for $50 million ($112M in 2021). But this was not good enough for the people of Glen Ridge, some of which who came together as the grassroots campaign the Lorraine Street Committee for a Radium Free Glen Ridge, which stepped up to fight and organize. They were able to, through political pressure and connections, fight the EPA and demand the very best possible cleanup. Although this could be considered a big win for the residents of Glen Ridge, can we say with certainty that the biggest decider in this issue was not the ethnicity and income level of those most impacted by radiation? Why did Glen Ridge receive such a hasty and complete remediation when there are over one thousand active Superfund sites across the United States, many of which are in close proximity to minority neighborhoods, that are sitting unaddressed, causing danger and negative health effects to those forced to live near (or on) them? This paper will discuss how Glen Ridge wound up as a radium depository, how this radioactive danger was rediscovered, and analyze how the EPA cleaned it up with comparison to other dangerous superfund sites across the country.

Burial:

Glen Ridge began its life originally as a part of the neighboring Bloomfield, which was in itself a part of New Ark, a purchase of land from the Lenape Tribe of Native Americans all the way back in the 1600s. Glen Ridge was largely farmland and wooded fields, but had a decent industrial center along the banks of Toney’s Brook, which flows through the town. There was a copper mine and sandstone quarry, as well as three mills, powered by the brook, that produced lumber, calico, pasteboard boxes, and brass fittings. The entire area, including Glen Ridge, Bloomfield, Newark, and more, was a huge center for early industrialization during the industrial revolution of the 1800s and stayed that way until after World War II, when more manufacturing started moving to Asian countries for economic reasons. Regardless, this is to say that Glen Ridge and its surrounding area had a large economic and production output, especially at the time when our story begins.[1]

In 1903, Marie Curie, along with her husband Pierre Curie and collaborator Henri Becquerel received the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing theory on what she called “radiation”. What people knew about it at this time was that it is a source of energy, and it had medical applications as well. Curie herself helped to pioneer the use of radioactive isotopes to cure “neoplasms”, a type of abnormal and excessive tissue growth[2]. What people, however, did not know, was the nature of radioactivity and the many ways it can spread and have adverse effects on the human body. [3]

In 1917, in Orange, New Jersey, just a few blocks away from the eventual Superfund site in Glen Ridge, the United States Radium Company opened its factory. During WWI, radium-based paint was used on the dials of aircraft so pilots could better see them while flying at night. When the war ended, it left an entire industry devoted to the mining, processing, and application of the radium paint. With a normal post-war economy returning, focus was shifted from military applications to instead painting glow in the dark watch and clock faces.[3]

At the US Radium Co plant, the radium was processed from ore form to the finished product, the luminescent paint named “Undark”. This process created a lot of waste, from the left over dirt, rock, and uranium from processing the ore, to the leftover barium after it had been chemically separated from the radium [4]. This waste had to find a home somewhere.

During the 1920s, America was experiencing a large growth in the suburbs, driven by the growing ubiquity of the automobile in middle class (and up), a strong post-war economy, and the development of more affordable homogenized housing (like from the Sears Catalog). Because of these factors, the 1920s were the first decade to experience suburban growth surpass urban growth[5]. Glen Ridge was at the intersection of this, with its large open fields providing ample space to build homes, and its train stations providing easy rail travel to Hoboken and New York City. It was in this way that a residential neighborhood (in planning) became a match made in heaven for tons and tons of radioactive soil.

Concurrently, within the United States Radium Corporation, the story of the now-ubiquitous Radium Girls unfolds. US Radium (along with other companies across the country) employed, over the course of 1917 to 1926, approximately 300 dial painters, almost all of them young women from the surrounding area.[4] The US Radium company told these women that the radium paint the were working with was harmless, and it was standard procedure for the painters to lick paintbrushes in between painting dials to reshape the brush head. [6] The painters would also often paint their nails, teeth, and skin as well, and were sometimes even referred to as “ghost girls” as they would glow in the dark from the radioactivity. The injustice here was that the plant’s chemists worked with the radioactive material using long tongs and lead shielding as they knew what would happen if they got too close.[6] Pierre Curie said in an interview that “he would not care to trust himself in a room with a kilo of pure radium, as it would doubtless destroy his eyesight and burn all the skin off his body, and probably kill him”.[7]

As early as 1917, deteriorating health conditions had been displayed by the women. In 1922, Grace Fryer, who had previously been a painter, now serving as a bank teller, visited a doctor after her teeth began to loosen and fall out. Using an early x-ray machine, the doctor discovered that her jaw was riddled with small holes, similar to Swiss cheese. A series of doctors attempted to find the underlying cause of this, and it was found that there were multiple women suffering from the same ailment. The unifying factor between all these women was that they had been dial painters at US Radium. US Radium’s first move was to conceal this news naturally. Fryer was examined by a “specialist” from Columbia University, who declared her to be in fine health. This specialist, however, was a toxicologist who worked for US Radium and his “colleague”, who had been present during the examination to confirm the diagnosis, was actually one of US Radium’s vice presidents.[6] US Radium also accused these girls of contracting syphilis in an attempt to smear the girls and divert blame from themselves.[7]

Eventually, despite US Radium’s best efforts to prevent it, litigation began against the company. In 1928, Grace Fryer and four other women sued for damages to their health. Two of these women were bed-ridden, and none were able to raise their arms to take an oath. Grace was unable to walk, had lost all her teeth, and required a back brace to sit up. The girls ended up winning a settlement for $10,000 and $600 per year while they were still alive, but, as the last of the girls died in the 1930s, few of these yearly payments were ever collected. It was found later on that the girls consumed hundreds to thousands times the recommended dose of radioactivity. [6] Following the settlement, US Radium closed its plant in Orange, and moved its operations to New York, leaving the irradiated facility, and the tons of radioactive dirt and rubble that would soon find its way to Glen Ridge’s growing suburbs.

Discovery:

On March 28, 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor, near Middletown, PA suffered a partial meltdown. This was the most serious incident at a US nuclear power plant in history. Despite the small radioactive release having no detectable health effects on plant workers or the public, the incident drastically changed the training, oversight, and emergency response planning for reactors across the US, significantly enhancing reactor safety, while also bringing the dangers of radiation into the eyes of regulatory bureaus.[8] Following conferences in Washington DC on the subject, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) initiated a program to identify and investigate locations that had been used for radium processing. The old US Radium Corporation plant in Orange was one such location that was to be revisited because of concern that the plant’s waste had been dumped offsite. {9] Therefore, a county-wide aerial gamma radiation survey was ordered to determine the possibility of improper disposal.[10]

What the NJDEP survey detected is that locations in Glen Ridge, as well as neighboring Montclair, had high levels of gamma radiation, indicating that it was likely that waste had in fact been dumped at these sites. The soil had been spread across 130 acres of land, on which there were 430 residential properties and 14 municipal properties. Not only had the soil been dumped as landfill, it had also been used as an aggregate in cement used to make sidewalks and home foundations. These homes were found to have high amounts of radon gas and radon decay particles along with excess levels of indoor and outdoor gamma radiation that exceeded federal and state exposure limits. [11]

This site was immediately designated as a Superfund Site by the EPA, part of a brand new program designed to identify, monitor, and clean up uncontrolled or abandoned hazardous waste dumps across the United States. [12]

In 1983, the EPA began preliminary investigations into the extent of contamination in both the Glen Ridge and Montclair sites. The first order of action was to install ventilation systems and radiation shielding in houses with excess concentrations of radon gas, a radioactive gas that is a byproduct of the radon breaking down in the foundations of the houses. In some of these houses, the radon levels were almost 100 times the safe limit.[13] This had a quantifiable health risk in the form of increased rates of lung cancer for those who lived in these residences.[14] As an immediate response, a quarterly monitoring program, along with the ventilation, was initiated for these homes, to keep an eye on the level of radon gas while studying the site and formulating a plan.

In 1984, the EPA began its Remedial Investigation and Feasibility Study (RI/FS) to determine the full extent of contamination as well as list plans and alternatives for cleanup. While this study was conducted, the NJDEP initiated its own pilot program to excavate the radioactive soil. This program lasted from 1985 to 1988, where four contaminated properties were fully remediated.[14] Five properties, however, were left incomplete when the state of Nevada, where the radioactive soil was to be shipped post removal, revoked the permit to dump the soil there. This soil sat in Kearny and around the partially remediated properties until a disposal facility in Utah was found in 1988. [15]

Concurrently, the EPA had released its RI/FS to the public in 1985. Its plan was to install more ventilation and shielding for houses with excess radon gas and gamma radiation. The quarterly monitoring program would also be continued. While it did indicate that excavation of the soil would be the preferred method of cleanup, the EPA decided that removing the radioactive soil would be expensive and difficult to do, largely due to the lack of viable disposal locations.[16] On top of this, the remediation would be a massive undertaking: the soil spanned multiple properties, a large park, and was under roads, foundations, and sidewalks. It therefore began a second supplemental feasibility study to find ways in which it might clean up the site without having to go through the process of excavation and relocation.

In 1989, the EPA held a public meeting to announce the latest iteration of its plan to clean up the Superfund site. The houses that contained the most contamination would be fully cleaned up: all the radioactive soil would be removed. However, for homes with less severe radiation issues, or with hot spots located outside the home itself, “Engineering controls” and “Institutional Controls” would be established.[14] These would be physical barriers between the people and the radiation and deed restrictions that would prevent homeowners current and future from doing things such as digging in their own backyards in order to prevent trapped radon gas from escaping.[16] Simply put, this remediation would still leave a lot to be desired: the radioactive soil would stay on these properties, require constant monitoring by the EPA. This would negatively effect home value, as now not only were homes located on radioactive waste but were legally limited to what a prospective homeowner could do to their own property. On top of all of this, these homeowners would have to live with the knowledge that, although contained and monitored, they had radioactive waste in their yards.

The People Step Up

The sudden knowledge that many houses were located on or near a radioactive soil depository caused a buyer’s market for these properties as homeowners fled their potentially dangerous neighborhood. However, this did not translate into the new buyers being aware of what exactly they had just moved themselves into. For example, when Steve and Anne Sutton moved to Glen Ridge in 1993, they discovered a box of warranties and tax bills from the previous owner. Also in this box was a letter from the EPA detailing the situation. They understood why their bid of $17,000 under asking price was accepted immediately, and at that point it was too late to do anything about it. Carl Bergmanson and his wife Ruby Siegel (who was pregnant at the time) moved to Glen Ridge in 1988. They only found out a year later when they received a notice from the EPA informing them of a meeting to discuss remediation of the radioactive waste in their own backyard.

In this 1989 meeting, the EPA announced its plan to fully remediate the most dangerous houses and place the “barriers” at less contaminated zones. But the people of Glen Ridge were not satisfied by this by this course of action. Kit Schackner, another resident, after hearing Mr. Bergmanson speak at the meeting, visited him at his house (on Lorraine Street) and in less than a month, the Lorraine Street Committee for a Radium-Free Glen Ridge had been established.

The Lorraine Street Committee was going to try to make as much noise as they could in order to get the cleanup they deserved. Their first move was to get the EPA to extend its deadline for commenting on the plan. They were granted this, and Kelly Conklin, husband of Mrs. Schackner, began making calls to Washington D.C. to find political allies willing to help their cause. They came into contact with Congressman (and future Governor) James J. Florio and Senator Frank R. Lautenberg, the latter of whom was a large proponent of the Superfund program. They also got other impacted people, neighbors, and anyone else in town who would, to write letters to Congress asking them to help out. John Frisco, the EPA agent in charge of operations in New Jersey said that “In terms of public outcry, it was one of the most dramatic that I’ve ever experienced in my career”. In the end, the efforts of the Committee paid off, and Senator Lautenberg was able to organize a meeting between the Lorraine St Committee and the head of the Superfund program in Washington D.C. The EPA agreed to a complete cleanup, or “remediation”, and all the radioactive soil would finally be removed, over half a century after it was originally placed there. [13]

Retrospective:

Glen Ridge’s cleanup took 17 years and cost an estimated $150 million. The total cleanup, between Glen Ridge and its sister site in Montclair was, at the time, one of the largest cleanups ever, on a similar scale to the Love Canal cleanup in Niagara Falls, New York. Streets had to be evacuated, a park was closed off, and at least two badly contaminated houses were completely torn down and rebuilt. It was also one of the longest and most controversial environmental cases of its decade, with battles between New Jerseyans and rural communities that would have to shoulder the burden of accepting the six million cubic feet of radioactive soil after it was dug up and removed.[16] It is important to remember that Glen Ridge’s victory over the EPA’s less-than-adequate clean up plan did not occur in a vacuum, however, and there are multiple things that may help us contextualize how exactly such a victory over the EPA was won.

In the modern day, across the country, there are more than 1300 Superfund sites. Around 700 of these have been on the list for close to 40 years, since the Superfund program was established in the wake of the Love Canal tragedy. In this time, the EPA has cleaned less than 400 of these sites.[17] If this seems bad, we can zoom out even further: in 1980, across the United States, there were over 400,000 toxic waste sites speculated to be in need of cleanup. Only 400 of these sites, identified as needing immediate attention, made it onto the National Priorities List (NPL). Glen Ridge and its sister sites were one of the first to be added to this list.

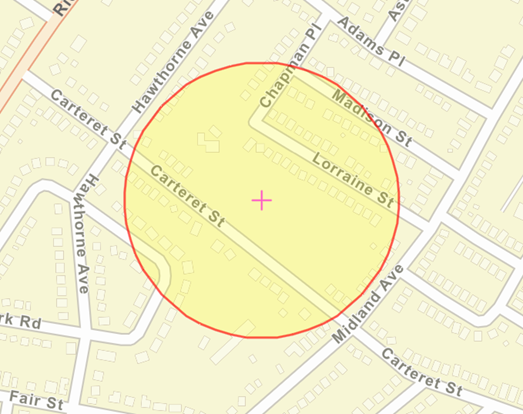

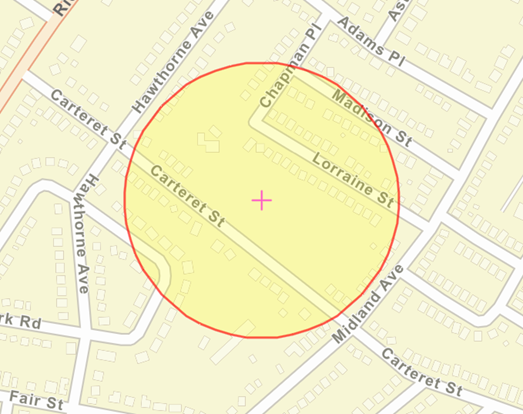

To contextualize this further, we can look specifically at Glen Ridge and the demographics of the people located around this site. We can find this information by using ejscreen.epa.gov, a website tool that lets the user obtain demographic records around a selected location. The main area that the soil was dumped at is Carteret Park/Barrows Field, and a .1 mile buffer zone is chosen to capture both Lorraine Street and Carteret Street, both of which required the most cleanup. In this 0.03 square mile area, the population is almost 80% white, 65% college educated, and 85% English-only speakers.[20]

Figure 1: Buffer Zone around the Site (r = .1 miles)

As we can see from the graph below from the 2010 Census, the area around this site is 79% white, with 9% Black and 6% white. Glen Ridge is a predominantly white town and, even when taking a small sample like this, we can see that.

Figure 2: Census Data for Selected Zone (2010)

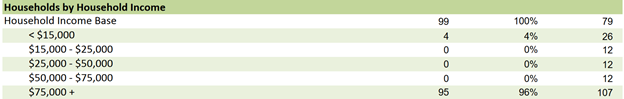

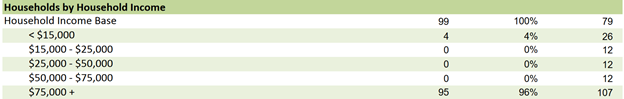

According to the figure below, the vast majority of households around the site are also earning more than $75,000 a year. If we take average yearly wages in America to be $51,000 a year, the people that live here are earning 68% + more than average (taking only $75,000 a year into account).

Figure 3: Income Breakdown of Area Around Site

Additional data shows us the education levels of people living around the site. We can see that the vast majority of people have a Bachelor’s Degree or higher, with almost everyone else having at least a High School diploma. Compared to 37.5% in the United States, this is significantly higher.

Figure 4: Education Levels Around Site

Finally, this data shows us that the majority of people around this site are fluent in English, with only 4% of people reporting speaking English “less than very well”.

Figure 6: Language Breakdown Around Site

In comparison, a report published by the Shriver Center on Poverty Law found that 70% of Superfund sites across the country are within a mile of public housing. The report included a case study on the contaminated West Calumet Apartment Complex, in East Chicago, Indiana, where, for over 40 years, families did not know that the soil beneath them was highly contaminated with lead and arsenic. They were not told about this until 2016 when the EPA alerted them to the presence of the toxins.[18] East Chicago, and the area within .5 miles from this site, is almost 70% black, with only 4% of residents having a college education and 33% earning below $15,000 a year.[20] This is the complete opposite of Glen Ridge and the area surrounding the radium Superfund site.

After legal action, the residents were given relocation services, expanded timelines for moving out, rent abatement, and lead hazard risk assessments in replacement housing for those families with children containing elevated levels of lead in their blood. The EPA also preformed some remedial duties including sampling drinking water, dust, and basement water, as well as sampling more residential properties to determine if lead levels were too high. These people are still, to this day, fighting for better restitution from the EPA despite signs of elevated lead exposure since 1985. The complex has now been demolished, but it serves as an insight into the reality that many poorer and minority groups have to deal with. [18]

When the EPA addressed the West Calumet Apartment Complex, they begrudgingly, after litigation, offered to help residents move out and test their new homes for lead and other contaminants. The complex was demolished subsequently.[19] When the EPA addressed Glen Ridge, they became renovators, photographing the houses in every detail, doing their best to return the houses to exactly how they had been before remediation, including landscaping, and, in one case, an elaborate rose garden that needed to be replanted.[20] Demolishing houses, permanently relocating residents, and cordoning off the site was never even an option.

Conclusions

It is incredibly difficult, if at all even possible, to tag a concrete yes or no answer to the question “did Glen Ridge’s demographics help them achieve a better response”. There are simply too many intersecting factors to say for sure. Undoubtedly, the battle the Lorraine Street Committee fought was a hard won victory, taking many phone calls, letters, and meetings before they were able to secure the cleanup that they wanted and deserved. As James Frisco of the EPA said, it was one of the most dramatic outcries he had experienced in his years at the EPA. But the one thing we can be certain on is that Glen Ridge’s cleanup was unique in that it went far beyond the scope of many other Superfund cleanups. For most sites, as the EPA originally had planned for Glen Ridge, fixing the problem manifested in a series of stopgaps, with remedial measures designed to keep costs low while the underlying issues remained unaddressed, giving as little help to those impacted as could be done to get by. And how do the other 1000+ Superfund sites that have outlasted Glen Ridge’s stay on the EPA’s National Priorities List across America look like today? Probably not like the picturesque and tranquil suburb, showing no trace of the radioactive nightmare that until fairly recently lurked just below the surface.

Endnotes

1. “Glen Ridge, New Jersey,” Wikipedia.org, December 13, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glen_Ridge,_New_Jersey.

2. “Marie Curie,” Wikipedia.org, December 13, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Curie.

3. “Significant Discoveries and the History of Radiation Protection,” United States Department of Environmental Protection, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/documents/significant_discoveries_history_radiation_protection-worksheet_rp_1.pdf.

4. Carl Willis, “U.S. Radium, Then and Now” Special Nuclear Material, A Carl Willis Joint, WordPress, May 14, 2012, https://carlwillis.wordpress.com/2012/05/14/u-s-radium-then-and-now/

5. Timothy Berg, “Suburbia,” Encyclopedia.com, May 18, 2018, https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/art-and-architecture/architecture/suburbs.

6. Alan Bellows, “Undark and the Radium Girls,” damninteresting.com, December 2006, https://www.damninteresting.com/undark-and-the-radium-girls/.

7. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, “Radium Girls; The Story of US Radium’s Superfund Site,” March 19, 2016, https://www.state.nj.us/dep/hpo/1identify/nrsr_19_Mar_Radium_girls.pdf.

8. United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission “Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident,” nrc.gov, 21 June,2018, https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html.

9. J.V. Czapor, K. Gigliello, J. Eng, “Radon contamination in Montclair and Glen Ridge, New Jersey: Investigation and emergency response,” International Nuclear information System (INIS), December 13, 2021, https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:19064054.

10. Energy Abstracts for Policy Analysis, Volume 14 (Office of Scientific & Technical Information, United States Department of Energy, January 1988), pg 338.

11. “Glen Ridge Radium Site Glen Ridge, NJ,” epa.gov, United States Department of Environmental Protection, December 13, 2021, https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0200996#bkground.

12. “Superfund History,” epa.gov, United States Department of Environmental Protection, December 13, 2021, https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-history#1.

13. Debbie Galant, “Living With A Radium Nightmare,” New York Times (New York, NY), Sep. 29, 1996.

14. “Site Review and Update; Montclair/West Orange Radium Site, Glen Ridge Radium Site,” state.nj, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Revised 2 June, 1993, https://www.state.nj.us/health/ceohs/documents/eohap/haz_sites/essex/glen_ridge/glenridge_radium/grmtclwo_sru_6_93.pdf.

15. R. Pezzella, P. Seppi, D. Watson, “Case Study: Montclair/West Orange and Glen Ridge Radium Superfund Sites,” International Nuclear information System (INIS), December 13, 2021, https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:26028962.

16. Anthony Depalma, “U.S. to Clean Radium Sites In Three Towns,” New York Times (New York, NY), June 7, 1996.

17. Jessica Morrison, “Polluted sites linger under U.S. cleanup program,” Chemical & Engineering News, American Chemical Society, April 3, 2017, https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i14/Polluted-sites-linger-under-US-clean-up-program.html.

18. Shriver Center for Poverty Law, “Poisonous Homes; The Fight for Environmental Justice in Federally Assisted Housing” (Earthjustice, June 2020), 1-112.

19. Eliot Caroom, “EPA wraps up long cleanup of U.S. Radium pollution in Essex County,” nj.com, The Star Ledger, May 4, 2009, https://www.nj.com/news/local/2009/05/epa_wraps_up_long_cleanup_of_u.html.

20. ejscreen.gov, United States Environmental Protection Agency, https://ejscreen.epa.gov/.

Bibliography

“.” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. . Encyclopedia.com. 24 Nov. 2021 .” Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com, December 13, 2021. https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/art-and-architecture/architecture/suburbs.

“Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident | Nrc.gov.” Backgrounder on the Three Mile Island Accident. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html.

Bond, Michaelle. “Seventy Percent of Superfund Sites Are within a Mile of Public Housing, Report Finds.” https://www.inquirer.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 15, 2020. https://www.inquirer.com/news/environmental-justice-superfund-nj-shriver-center-20200714.html.

Czapor, J V, K Gigliello, and J Eng. “Radon Contamination in Montclair and Glen Ridge, New Jersey: Investigation and Emergency Response.” Energy Abstracts for Policy Analysis 14 (n.d.). https://books.google.com/books?id=TX8Y3n7vaGkC&pg=PA338&lpg=PA338&dq=How+did+NJDEP+discover+radon+gas+glen+ridge&source=bl&ots=5BPofWXvIn&sig=ACfU3U1PNPCisTSrpuZzEPhD7Fwf9ly7Nw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjts73Vv_rzAhWDdd8KHaF5De8Q6AF6BAglEAM#v=onepage&q=How%20did%20NJDEP%20discover%20radon%20gas%20glen%20ridge&f=false.

Czapor, J.V., K. Gigliello, and J. Eng. “Radon Contamination in Montclair and Glen Ridge, New Jersey: Investigation and Emergency Response.” inis.iaea.org, January 1, 1984. https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN%3A19064054.

Depalma, Anthony. “U.S. to Clean Radium Sites In Three Towns.” The New York Times, June 7, 1990.

Division of Occupational and Environmental Health, Judith B. Klotz, Julie R. Petix, Angela D. Gilbert, Joseph E. Rizzo, and Rebecca T. Zagraniski, https://www.state.nj.us/health/ceohs/documents/eohap/haz_sites/essex/glen_ridge/glenridge_radium/grmtclwo_mortrpt_5_88.pdf § (1988).

“EJScreen Tool.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://ejscreen.epa.gov/.

“Environmental Justice Report – Shriver Center on Poverty Law.” Shriver Center on Poverty Law. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.povertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/environmental_justice_report_final-rev2.pdf.

Galant, Debbie. “Living With A Radium Nightmare.” The New York Times, September 29, 1996.

“Glen Ridge Radium Site Site Profile.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, October 20, 2017. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id=0200996#bkground.

“Glen Ridge, New Jersey.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, November 15, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glen_Ridge,_New_Jersey.

Kummer, Frank. “EPA Finalizes $72M Cleanup Plan for S. Jersey Superfund Site. Sierra Club Calls It a ‘Band-Aid.’.” https://www.inquirer.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 12, 2019. https://www.inquirer.com/science/superfund-site-epa-matteo-west-deptford-gloucester-county-20191112.html.

Morrison, Jessica. “Polluted Sites Linger under U.S. Cleanup Program.” Cen.acs.org. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i14/Polluted-sites-linger-under-US-clean-up-program.html.

Northeast Region Philadelphia Support Office, Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data §. HAER No. NJ-121-A (n.d.).

Person. “Undark and the Radium Girls.” Damn Interesting. Damn Interesting, July 27, 2019. https://www.damninteresting.com/undark-and-the-radium-girls/.

“Preservation Snapshot,” March 19, 2016. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/hpo/1identify/nrsr_19_Mar_Radium_girls.pdf.

“Radioactively Contaminated Sites.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.epa.gov/radtown/radioactively-contaminated-sites.

“Significant Discoveries and the History of Radiation Protection.” EPA.gov. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/sites/static/files/2018-12/documents/significant_discoveries_history_radiation_protection-worksheet_rp_1.pdf.

Site Review and Update, Glen Ridge Radium Site, CERCLIS No. NJD980785646 § (1993).

Star-Ledger, Eliot Caroom/The. “EPA Wraps up Long Cleanup of U.S. Radium Pollution in Essex County.” nj, May 4, 2009. https://www.nj.com/news/local/2009/05/epa_wraps_up_long_cleanup_of_u.html.

“Superfund History.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-history#1.

“United States Radium Corporation.” United_States_Radium_Corporation. Accessed December 13, 2021. https://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/United_States_Radium_Corporation.html.

Wakin, Daniel J. “New Jersey Town Cleans up 60-Year-Old Contamination from Watch Dial Industry.” AP NEWS. Associated Press, June 21, 1985. https://apnews.com/918b06bcf9bf2eb7b5d3e9dc848cf366.

Walker, S, B Donovan, M Taylor, and M Aguilar. “11 – Managing Site Remediation: the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund Program.” Managing Nuclear Projects, 2003.

Willis, Carl. “U.S. Radium, Then and Now.” Special Nuclear Material, April 10, 2017. https://carlwillis.wordpress.com/2012/05/14/u-s-radium-then-and-now/.

Zagorsky, Jay. “Why Did People Flee the Inner Cities?” Jay Zagorskys Research Blog, June 23, 2014. https://u.osu.edu/zagorsky.1/2014/06/23/fleecities/.

Primary Sources:

- This is a new york times article written during the cleanup that talks about the interaction with residents and the toxic site. It was written by Debbie Galant in 1996, in the middle of the cleanup. This article helps me understand the relationship between residents and the radioactivity as well as information on the grassroots activist group that arose from this issue. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/29/nyregion/living-with-a-radium-nightmare.html?ref=oembed

- This is an EPA publication from the early 1990s that discusses the steps that had been taken in remediation along with those that needed to be made already. This document is available on the state of NJ’s website. It is an important source for me as it tells me the component of the EPA/state government’s part in the story during the cleanup of the site. https://www.state.nj.us/health/ceohs/documents/eohap/haz_sites/essex/glen_ridge/glenridge_radium/grmtclwo_sru_6_93.pdf

- This website from the library of congress has two accounts of written and historical data of the US Radium CO factory where the radioactive waste came from. It also includes a bibliography including more information pertinent to this site and story. The website itself also includes photographs of the factory, which, while not helpful to this paper, is still interesting. These articles help me understand the situation ongoing in this area at the time and gives me a little more insight as to what happened in between when the factory shut its doors and when the EPA got involved with cleanup. https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.nj1644.photos?st=gallery

Analysis:

(Source 1) This source is a new york times article written during the time of the cleanup and it details interactions with Glen ridge citizens through interviews of homeowners both new and old. The point of this article is to show that citizens of Glen Ridge were largely unaware of the fact that there was any sort of danger posed to them.

The author achieves this goal from interviews. Firstly, “But in Glen Ridge, you could spend all day walking around the 90-acre site — this utterly typical neighborhood of 1930’s houses on shady streets, of flower gardens and jungle gyms and dogs — and never guess the source of the contamination” provides a juxtaposition of the idyllic suburb with the level of contamination, and also highlights how unapparent the danger is. “And there, in the box, was a letter from the E.P.A. Suddenly they understood why they got such a great price on the house. They tried to see if they could stop the deal, but it was too late. The lawyers were all gone and the seller was driving to Arizona” is a summary of a story told in an interview from a resident which gives insight into how some residents came to be aware of the issue on moving in and further shows how hidden they tried to keep the issue. “We got a notice in the mail from the E.P.A. about a meeting,” said Mr. Bergmanson. ”It said something like, ‘As you know, you are part of a Superfund site radium cleanup . . . .’ And we were like, ‘What the heck is this?” is a quote from an interview with another glen ridge resident and shows further how unaware people were of the danger that they were living on top of

Secondary Sources:

1. Galant, Debbie. “Living With A Radium Nightmare.” New York Times, 29 Sept. 1996, p. 13.

This is an article written specifically about Glen Ridge residents’ lack of knowledge, and response to, the radium buried under their properties.

This source talks about how people were originally unaware of the danger, or even presence, of radium in Glen Ridge. It talks about individual reactions (of people I personally know) to discovering the situation. It also introduces the Lorraine Coalition for Radium-Free Glen Ridge, which was a grassroots movement within the community that caused commotion about this danger, and got it established as an EPA Superfund Site. This article is an important insight into the personal side of the issue, and shows a lot about how individual families were burdened with it.

2. United States, Congress, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, and Remedial Programs Branch. Site Review and Update. June 2, 1993. Click to access grmtclwo_sru_6_93.pdf

This source is a government publication that gives an overview of the government side of the cleanup effort.

This source is important for my paper as it gives me insight to the government’s response in a factual manner. It details the EPA’s involvement in the case, and what actions were taken when, and why. It also talks about the site, the dangers, and the response. This source will help me understand what was going on with the government and EPA during the cleanup.

3. Willis, Carl. “U.S. Radium, Then and Now.” Special Nuclear Material, 10 Apr. 2017, https://carlwillis.wordpress.com/2012/05/14/u-s-radium-then-and-now/.

This source is a website maintained by a nuclear scientist who discusses the nature of the radiation and the factory in Orange it came from.

On this website, the author discusses the more scientific side of this issue. He talks about how the factories operated, and the dangers in them, as well as how the issue of the radium girls ties in. He also talks about how radioactive material was processed, and where it came from. This is important as it gives me insight into the more scientific side of the issue.

https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2019/03/radium-girls-living-dead-women/

Image Analysis:

Data Analysis:

Introduction

When the US Radium Corporation shut its doors in 1926, radioactive landfill was used to fill in some low lying areas in town for development. These areas were primarily around Carteret Park in Glen Ridge. Therefore, this park serves as the center of the buffer zone. A .1 mile radius was chosen as it includes most of the area impacted. The radius is small as the radioactivity did not spread. Being underground / in foundations and sidewalks meant that it was (despite being dangerous to those living on it) largely contained within the area it was originally put. EPA surveys of groundwater in the area determined that the groundwater was not sufficient enough to spread the radioactivity. This buffer zone includes Lorraine St, of the Lorraine Street Coalition for a Radium Free Glen Ridge, where several houses built had large traces of radium, and Carteret St, another site impacted by the radioactivity. Due to its circular geometry, the buffer zone includes areas that were not impacted but because of the size of the radius, it still gives good insight into the community around this area.

Figure 1: Buffer Zone around the Site (r = .1 miles)

Environmental Data Analysis

At this site, the level of cancer risk, respiratory illness, superfund proximity and hazardous waste proximity are above 50% as compared to the rest of the country. This indicates a very high danger. The radon gas found in houses is likely the direct culprit of the cancer and respiratory illnesses. As we can also see, the superfund proximity is almost 100%, as this is in fact the location of a (now remediated) superfund site. This data suggests that the people living around this area are at a significantly higher risk of side effects of radiation than most people in the country.

Figure 2: Environmental Indicators Around Site

Demographic Analysis

Figure 3: Census Data for Selected Zone (2010)

As we can see from this graph from the 2010 Census, the area around this site is 79% white, with 9% Black and 6% white. Glen Ridge is a predominantly white town and, even when taking a small sample like this, we can see that.

Figure 4: Income Breakdown of Area Around Site

As we can see from the figure, the vast majority of households around the site are earning more than $75,000 a year. If we take average yearly wages in America to be $51,000 a year, the people that live here are earning 68% + more than average (taking only $75,000 a year into account).

Figure 5: Education Levels Around Site

This data shows us the education levels of people living around the site. We can see that the vast majority of people have a Bachelor’s Degree or higher, with almost everyone else having at least a High School diploma. Compared to 37.5% in the United States, this is significantly higher.

Figure 6: Language Breakdown Around Site

This data shows us that the majority of people around this site are fluent in English, with only 4% of people reporting speaking English “less than very well”.

What this data all suggests is a white, English-fluent, well off, and well educated population. This data shows how the site in question does not match the typical qualities of the other sites discussed in the context of environmental justice. This also helps us understand better why it was that Glen Ridge was able to receive such a good cleanup when there are hundreds of thousands of other superfund sites across the country still unaddressed, many of which are located closer in proximity to more minority neighborhoods. Glen Ridge is the antithesis of places that the (REPORT we read about earlier in the semester) suggests as places where people are most likely to not fight the placement of a potentially dangerous waste site.

Conclusion

From our studies on environmental justice in the United States, a common denominator amongst the stories and studies is that uneducated minority neighborhoods tend to be taken advantage of by all sorts of entities. The sites around these people are specifically chosen to minimize resistance to the dangers the sites can cause. Another theme we see frequently is the actions to mitigate dangers in wealthier communities being stronger than those in poorer neighborhoods (like San Antonio’s flooding problems or Malibu/West Lake’s fire problems). We can see that Glen Ridge fits the second theme, where it received a very sufficient cleanup at its own behest because of political power (and, although conjecture, likely a lack of racism against them for fighting for themselves).

What makes Glen Ridge unique as well, is that the site where radium was dumped was not created malignantly with population taken into account. While there is not any evidence on the decision to locate the radioactive landfill, it is very unlikely that it was done in spite of the residents of this area, and though there might have been some knowledge that it happened (ie the NJDEP revisiting the site in the 80s), it was moreso an accident than somebody trying to take advantage of a local population. Therefore, it makes a good case study to evaluate how race and income level can effect cleanup opportunities as compared to other areas.