Detention Center’s contribution to environmental Injustice: How the built environment perpetuates racial oppression

by Baïna-Lyssa Jean

Site Description:

Although climate change affects every countries, the imminent devastating effects are highly felt by third world countries populations. Severe heat, heavy downpours and flooding creates extreme poverty for third world countries that rely heavily on scarce natural resources. Deforestation, drought, insecurity, lack of health care, forces population to seek a better life in other territories.

The United States has a larger immigrant population than any other country and their immigration infrastructure and laws has made it specifically difficult for non-white immigrants to be welcomed. The United States is home to the largest Haïtian migrant population in the world as they are fleeing violence, poverty, natural disasters etc. Being an Haïtian immigrant somehow makes you a criminal on American soil as the U.S. detains Haïtian immigrant seeking asylum in abusive detention centers, and separates parents from their children. This year the percentage of Haïtian families in detention increased to 44% of the total, which means that more Haitian families are being detaining than any other nationality in the U.S. Not only are Haitian families being detained more often, but they pay much higher bonds than other immigrants in detention, about 54% higher than other immigrants. Haitians also had the second-highest denial rate of asylum at 87%.

We will analyze a few detention centers as built system where environmental injustice are evident. Abusive unit placements, toxic exposure to chemical disinfectant, inadequate medical responses, sanitation and hygiene issues are a few components that will be analyzed. As well as the Haïtian immigration journey to the United State. These analysis will help understand the environmental injustice in the U.S. system.

What impact does climate change have on Haïti? Are the US immigration laws purposefully set up to reject Haitian migrants? What infrastructure partake in the criminalization of immigrants? How is the build environment of these detention centers able tp reject immigrant’s human rights? Why do detention centers resemble jails? Are Haitians still paying a price for defying white authorities by being the first free black country?

Final Report:

Introduction

Before the late 2000s, the United States of America has often been praised as the land of the free, a melting pot, a country of opportunity and a beacon of hope. This savior propaganda traveled globally through movies, music, news platforms, and other cultural expressions, to persuade many. Along with the idealistic image of being the number one country on the global stage, the best place to be, the United states projected an idea of safety. Many people, specially the ones fleeing persecution, climate change impact, and political wars have come to believe that the United States is in fact a place of refuge that they need to reach. From 2008 to 2014, an average of 26.4 million people were displaced each year by disasters brought on by natural hazards like floods, storms, earthquakes and other natural disasters.[1]

However, in the last fifty years, it is important to note that this idea of the United States, founded by immigrants, home to many generations of immigrants from all over the world, being a welcoming place for refugees has changed. As climate change and humanitarian crises are strongly felt in third world countries, many refugees fleeing these unbearable conditions are seeking protection in this promised land. Unfortunately, the welcome center to their imagined better life is actually an overcrowded detention center, with high security, chain-link fences, where their human rights and dignity are jeopardized. The built environment of these centers was not supposed to be carceral nor supposed to criminalize populations fleeing climate change or humanitarian crises. Instead the intent of these centers was to be a safe temporary transitional space while they await a governmental decision.

This experience by most refugees is not unique and has been part of the migration process of millions of Haitians. The United States is home to the largest Haïtian migrant population in the world, as they are fleeing violence, poverty, natural disasters.[2] Data obtained by the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (RAICES) in June 2020 revealed that 44% of families in a detention centers in Texas were from Haïti, that their bond is 54% higher than other immigrants and they have the second-highest denial rate at 87%. The story of Haitian refugees is an example of how the United States’ immigration policies have constantly endorsed and supported the racial status quo by interdiction, deportation, and detention of this nation’s migrants. Are Haitians still paying a price for defying white authorities by being the first free black country?

In the mist of racial turmoil, another United states system seems to be once more unjust towards and criminalizing a group based on race not only with its laws but also with it’s built infrastructure perpetuating environmental injustices like abusive unit placements, toxic exposure to chemical disinfectant, inadequate medical responses, sanitation and hygiene issues.

Although most laws and policies are put in place to marginalize and oppress minorities, the architectural profession and architect’s contribution to environmental injustice can’t go unnoticed as their role is to create, designs and build spaces for human betterment and comfort. My interest lies in analyzing how and why the architecture of the centers have evolved away from their original ideal to become more “prison- like” and the environmental unjust effect of this change on the Haïtian refugee community within these facilities in the United State.

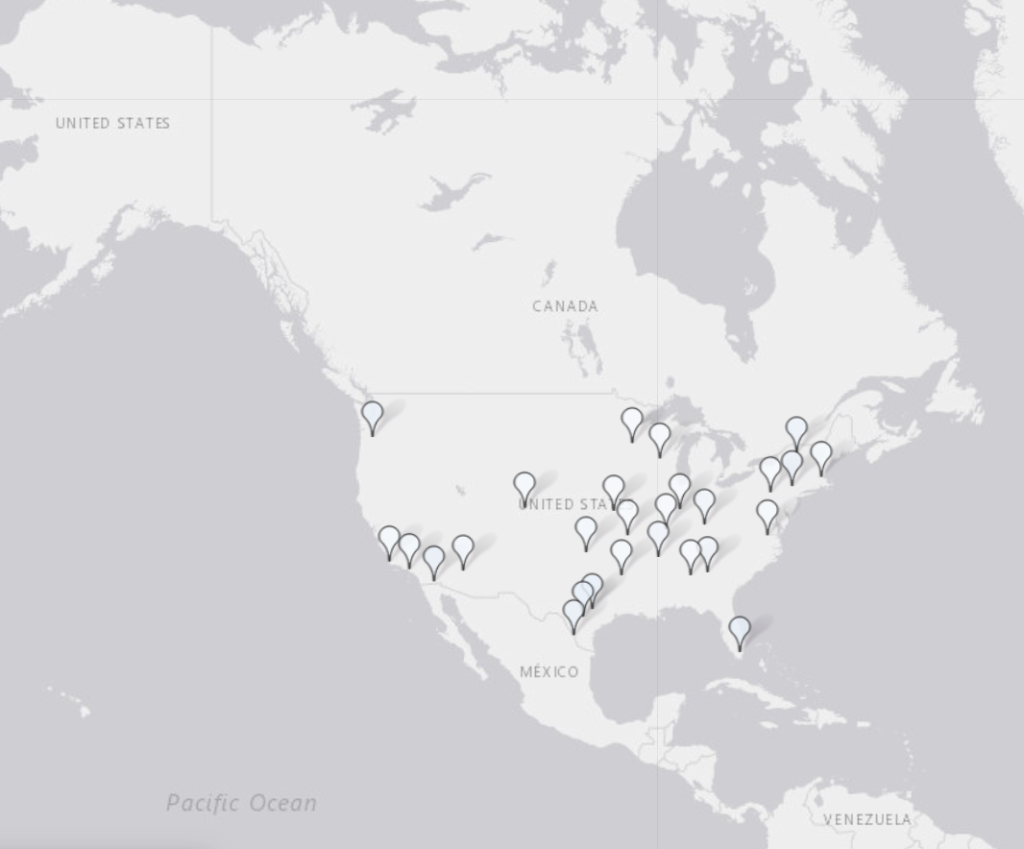

This essay will analyze the history of the Haïtian migration journey to the United states detention centers, from one environmental injustice to another by examining the climate change impacts that made them refugees to the human rights concerns happening in the United States detention centers by looking at news articles. Furthermore, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Office of Detention and Removal Operations, Contract Detention Facility Design Standards for Immigration and Customs Enforcement will be referenced to compare the general concept and design intent of detention centers to the built facilities. The freedom for immigrant’s interactive map will provide information on detention centers’ expansion throughout the years, the reported facilities with sanitation issues, toxic exposure and other.

Haitian immigrant and refugees’ journey to the United States

Haïti’s independence was proclaimed on January 1st 1804 and became the first free Black republic in the world as well as the first postcolonial country to be officially run by former slaves. The island was at the time a safe destination for many enslaved people from the Americas like Venezuela, Colombia, Costa Rica, northwest Brazil, Ecuador, who would seek refuge, knowledge and expertise from Haïti to gain their own independence. Two hundred years after its independence the immigration trend to the island drastically changed as more Haitians were emigrating elsewhere. Until the 1960s, most of the Haitian society remained rooted in Haïti, while just 5,000 Haïtians lived in the United States in 1960, migrants from Haïti began arriving in larger numbers from the frightful dictatorial regime of Jean-Claude Duvalier “Papa doc”, this era is known as the first mass migration of Haitians to the United States.[3] Most of the Haitians emigrating in that period were from the upper class and were able to migrate to the United states in a “lawful” way. But as the effects of the dictatorship were felt by all in the Haitian society, many of the lower class with no hope of a better future took it to the sea and became known as boat people and refugees.

An immigrant is often thought of as a person who willingly leaves their country to come to a new country to take up permanent residence; in the United States there are two types of immigration status that exist: citizens, residents. A refugee is a displaced person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster; in the United States, there are different types of refugees, the most commonly known are asylum seekers, stateless refugees, climate change refugees, hunger refugees. When talking about people coming to live permanently in the United States, it is important to understand that not everyone is willingly choosing to move, for many it is the only option to survive. With this understanding of those words, many Haitians heading to the United States from the 1960s to now are considered refugees.

Since 1972 the Haitian boat people have been arrested, jailed, and denied asylum, but that didn’t stop them as when faced with poverty, and political instability, the idea of the unknown might be worth the risk. The US-Haitian refugee crisis began in 1991 when the United States President Reagan changed the “entrants” immigration policy enacted by his predecessor Carter, and sent the United States coast guard to intercept and repatriate Haitian boat people. He then jailed the few refugees who made it to the United States’ Florida shores.[4]

Within one year, 44,570 legal Haitian immigrants arrived in the United States in 1980.[5] The perilous journey at sea to the southern shore of Florida was, for decades, a known route for Haitians boat people. And in that same year about 25,000 refugees arrived in makeshift boats to later be repatriated.[6] In 2004, as Haïti celebrated 200 years of independence, conditions on the island began to be drastically affected by mother nature. In May 2004, severe floods in the South left more than 2,000 dead; in September of that same year 3,000 were killed in the North due to the impact of tropical storm Jeanne.[7] As the rainy season and drought season became unbalanced, crops damaged, food scarcity on the rise and political conflict persisting after the overthrow of Aristide, the number of refugees fleeing by boat skyrocketed to new levels. By 2015, Haitians made up the largest immigrant group with more than 680,000 people in the United States with 1.5 percent of the total U.S. foreign-born population.[8] The United States has been the second largest contributor of greenhouse gas emission in the world from 1990 to 2018[9] and the negative contribution to the climate had a direct impact on third world countries like Haïti. While many Haitian refugees are forced to leave their home due to that negative impact on the climate, they are heading towards the country that has largely contributed to their displacement for hope and salvation.

In 2016, a new influx of Haitian refugees were located at the US Mexico border and placed in Texas detention centers. This finding by different news sources made me raise questions about their journey there. The journey to the United States from Haïti by boat is shorter and less perilous for the makeshift boats to the shores of Florida. Everyone with common sense should know that. How did Haitian refugees find themselves in Mexico? The answer lies with Brazil, the Brazilian government opened its doors to Haitians after the 2010 earthquake that killed more than 300,000 people on the island. By 2016, Brazil experienced an economic recession and Haitian refugees decided to cut through South and Central America, traversing 11 countries to find a way to the United States.[10] In an interview done by the Miami Heralds, Monelus told Jaqueline Charles“I wouldn’t wish this route on anybody because it is really dangerous. It’s not easy. A lot of people have lost their lives…We left Brazil and we were four. Now we are three. This really makes me sad. I really regret taking the trip. ”

Once at the US- Mexico border many refugees find themselves taken to a detention center, where they await a hearing from a judge. Although the process seems to be the same for all refugees, a few data collected by RAICES in June 2020 at the Karnes County residential center in Texas tells a different story. Haitian families made 44% of the total family in this detention center, and there are many components that are upholding and increasing this percentage. The disparity in the bond system does not allow the same opportunity of release to Haitian families. Bond is an amount of money that refugees in detention facilities can pay to be released while awaiting their appointment with a judge to review their case. RAICES was able to access the data on bonds paid by nationality and identified that Haitian refugees’ bonds were 54% higher than the bond of other refugees.

When Haitian refugees finally meet with a judge and request an adjustment of their status from illegal to an asylum, data obtain by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse university shows that from 2012 to 2017, Haitians had the second-highest asylum denial rate at 87%. Once these different components set up by the United States regulations against Haitian refugees are put into context, the fact that they account for 44% of the families in detention centers is no longer a surprise.

Detention centers’ role and purpose

As many Haitian refugee families find themselves in these detention facilities for longer than average period of times, it raises the question of the role and purpose of these centers. Detention centers are institutions where people like undocumented immigrants, refugees, are held in detention for short periods while awaiting the United States legal process that will determine if they are released or deported. Detention centers are legally known as “processing centers” and according to the United States supreme court, the instant proceedings of detained migrants are a civil act and assumed to be nonpunitive.[11] Nonetheless, these “processing centers” have the qualities and features of typical US jails.

The above image is a picture taken in 2014 by John Moore in a detention facility in McAllen, Texas. Moore has been able to capture many scenes inside of the United States detention centers, which haven’t been accessible to many. His pictures give a rare insight at the interior look of most recent detention centers, which helps understand people’s treatment within them. This particular picture was chosen, because of the clear overview of the built environment of this particular detention center. Due to the influx of immigrants, most of Moore’s pictures are usually filled with people; but the lack of people in this photograph give a clear sight of the components that frame the space.

The perimeter load bearing concrete masonry unit walls, provide an open space with little obstruction, which is ideal for sight. To keep consistent with the importance of sight, the separated spaces are made of chain-link fences which do not interrupt one’s vision and are ideal for supervision. Adding to the need of sight, a concave mirror is installed at the top of the fence, where a right angle corner is formed. Having a warehouse like open space, also allows for flexibility of reduction of expansion of spaces if needed. This allows them to accommodate more or less immigrants depending on the demand.

Assuming that the guard in the picture is six feet tall, the chain-link fences around the facility seem to be at least twice as high which would discourage anyone from climbing them. The door that allows access to the different sections, is also equipped with a number pad, which indicates that not everyone can move freely from one space to another. Only those provided an access code can.

There are no windows in the perimeter walls nor skylights, instead bright white lights are suspended from the ceiling. The idea of not having any fenestration, seems to be intentional, as not having sight of the outside can remove one’s sense of time and location. It’ll make the people in these processing centers forget how long they’ve been held in custody. Any without a sense of time, one can feel lost and powerless, at the mercy of others.

All of the previously mentioned components of the picture, if not given the location and context, would easily be identified as a jail. Therefore this idea of the US supreme court identifying these facilities as “non punitive” is removed from the reality of the brick and mortar facility. If it looks like a prison, acts as a prison, it must be a prison.

Another important aspect of the picture, the human aspect, helps understand what kind of people are found in these spaces, and how they are being used. At the center of the picture, a young child is found looking up at a television screen, where casper the friendly ghost is being played. The television is mounted on a plywood board, which indicates that it was a last minute thought, as wood isn’t found anywhere else in the facility. The child is performing a “child like” activity but not in a child-like place, as there is no place to seat and he is standing up to be entertained. Another striking element of this child is his feet; he isn’t wearing any shoes, which invoke two thing: that he can’t go too far and that the place that he is in, is more of a long term space for him to occupy, which when put in contrast with the guard who is wearing an uniform and shoes, evoke a temporary condition.

Other than the guard’s uniform, his posture and sight bring a lot of enigma to the picture. Although he is standing next to the child and his body is facing the camera, He isn’t looking at the photographer nor the child. Instead he seems preoccupied by something happening outside of the picture frame and has a grip around his belt, which could possibly be a gun. This raises the question of how dangerous can this child held in a detention center really be.

Architecture and its power to criminalize

This processing center like many others was built in the early 2000s, but it’s components and need for surveillance and control evoke Bentham’s 1791 Panopticon. His concept was to design an institutional building that allows all of its occupants to be observed by one authority. At the time, without the help of technology, it was impossible for one person to supervise multiple sections of the building at the same time, but Bentham was able to solve this issue by removing the occupants’ view and knowledge of when the authority was present or absent. By doing so the occupants are always motivated to act as though an authority was omnipresent. Bentham’s plan has been a great success and was widely used as prison’s floor plans. Michel Foucault, a french philosopher criticizes this form of incarceration as a “cruel, ingenious cage” that assures automatic power. The people arriving at the US detention center, like the Haitian refugees are already facing different types of trauma: leaving their home, families, going through a perilous journey to look for hope and a better life. Having components in place that can affect their mental well being is a way for authorities to exercise mental oppression.

With the design of the Panopticon, we can understand how the infrastructure of detention centers with an architectural concept can affect people’s mental and make them feel like they are doing something wrong and unwanted. In May 2007, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Office of Detention and Removal Operations published a Design Standards manual in which they present their Service Processing Centers’ operational components.

In the manual they call for an Office Components, a court and public detainee interface component, a detainee living component, a service component and a facility support component. The Office Zone provides a normal office setting for administrative and public functions of the Contract Detention Facility (CDF). The Office Zone is a non-secure area located outside the secure perimeter but requiring screening and control of the public entering the area. The Court Interface Zone includes the executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) work area and courtroom space, and is an interface area between the court personnel, the Removal Unit, the public, and detainees under restraint. The Detainee Living Zone contains functions that are used by detainees during their normal daily routine (recreation area, library). It is a secure zone with normal routine detainee movement within the primary secure perimeter. Components within this zone should be separated from each other by secondary secure perimeters. Detainee movement between each component will be monitored by housing security staff. The Service Zone provides services necessary for supporting detainees while they live in the CDF ( laundry, food preparation, health services). It is a zone that is located inside the primary secure perimeter with restricted detainee movement. Components should be separated from each other by secondary secure perimeters. Detainee movement to any component will be by direct escort or continuously monitored/controlled movement with staff control of each individual detainee passing into or out of a component. The Facility Support Zone provides support to the facility, though not directly to the detainees, and generally are not accessed or occupied by detainees. It is a zone that is a restricted area limited to staff and service vendors who provide vital services to maintain functions of the facility. With the description of the different components CDF explained, they provided a bubble diagram which shows the proximity of the different components and their relationships.

These descriptions of the different spaces and how the “detainees” are supposed to circulate with supervision, once again, raises the questions of these facilities functioning like prisons. Furthermore, the concept and diagrams of the design manual in contrast with the actual facilities photographs and videos, show how these facilities are overly crowded and aren’t properly used by authorities.

It is not expected to provide every refugee a five star hotel hospitality, but on the premise of detaining people following the United States immigration process, who aren’t serving a criminal sentence, nor pose a threat to the people around them, having to sleep on the floor in an overcrowded area shouldn’t be acceptable.

Detention center’s infrastructure as environmental injustice

The overcrowding of the Texas detention centers due to the surge of migrants at the border have contributed to the environmental injustices against the refugees, mostly of Haitian nationality detained in them. Gialluca, a lawyer at the Mcallen procession center in Texas states “Basic hygiene just doesn’t exist there…It’s a health crisis … a manufactured health crisis.” Another group of lawyers told the Associated Press about a group of 250 infants, children and teens, spent nearly a month without adequate food, water and sanitation.[12] The overcrowding of most detention centers in Texas made the state’s built center the worst in the country. In 2012, the Polk County detention facility and Houston processing center were forced to close. People reported waiting weeks or months for medical care; inadequate, and in some cases a total absence, of any outdoor recreation time or access to sunlight or fresh air; minimal and inedible food; the use of solitary confinement as punishment; and the extreme remoteness of many of the facilities from any urban area which makes access to legal services nearly impossible.[13] Unfortunately, the injustices against refugees aren’t only clustered in Texas, they also take place in other detention centers in the United States. In September 2020, Dawn Wooten, a nurse at the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia submitted a letter alleging forced hysterectomies and medical neglect at the Georgia detention center. The list of reports of wrongdoing in the United States detention center has a long history and is ongoing. Whether it’s abusive unit placement in 67 facilities, sanitation and hygiene issues in 87 facilities, toxic exposure to chemical disinfectant in 15 facilities, inadequate medical response and health service in 102 facilities, it is clear that refugees not only experience humanitarian crises but the built infrastructure of detention centers perpetuate environmental injustices.[14]

The inhuman treatment in these centers have been decades in the making, the growth and expansion of detention centers in the United States is visible when comparing the detention maps provided by Freedom for immigrants of 1983 and 2017. This expansion was necessary to accommodate the changes in US policies like the automatic detention of refugee mandatory implementation in the early 80s; the Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996; and with the creation of ICE in 2003. Having to match the implementation of these policies and laws was critical and allowed private companies to enter through contract with the United States government in the business of building detention centers. In 2014, 62 percent of immigrants in detention were housed in facilities run by private prison companies and in 2016, that share rose to 73 percent.[15] When faced with another influx of refugees in 2020, once again, authorities didn’t hesitate to overcrowd the detention facilities. A May 2020 report from the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general found 900 people crammed into a space designed to accommodate 125 at most.[16]

Detention centers by Private Companies

Private companies like CoreCivic, who also built prison facilities, state on their website that they partner with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to provide safe environments where detainees can reside temporarily as they go through their legal due process in the United States. Once more the statement of the ones building these facilities do not correspond to the reality of the built centers where people are safe nor in these spaces for a short period. In the about section of the CoreCivic website, none of the members of their executive leadership, board of directors, vice presidents have an architectural or engineering background, instead, the majority of them hold a business to finance degree. Businessmen are now responsible for the build environment of detention institutions, not trained architects and designers. Although they must have consulted and obtained advice from people with a design background, it isn’t hard to understand that the reason for the overcrowding of detention centers might be connected to a drive for profit. With the policies, laws and Immigration and Customs Enforcement ensuring the dentition of refugees, the business of detention centers is has a secured future and is highly profitable, but at the expense of human life.

Freedom for immigrant interactive map – Immigration Detention Centers in 1983

Freedom for immigrant interactive map – Immigration Detention Centers in 2017

Architects refusal to designing detention centers

Why are people with no design education handling the built infrastructure of detention centers and why aren’t architects and architectural organization more involved? In 2019 two organizations, The Architecture Lobby (TAL) and Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) state that they “continue to condemn the current administration’s assault on immigrant rights. These violent and racist policies are designed to cause fear and chaos; target those seeking asylum and refuge; and weaponize the built environment against immigrants.” Many architects and architectural designers have spoken against detention facilities but by removing themselves from the planning and design process, they allow non trained individual to tackle the tasks, which then reinforces people’s oppression in these buildings. The Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, in 2017, faced backlash when it called for its annual steel construction competition, asking participants to design a “Humanitarian Refugee (Detention) Center.” The protest of the architectural community made them cancel the competition and issue a different brief. The American Institute of Architects’ ethical cannon1.402 states that architects should not engage in conduct/ projects involving wanton disregard of the rights of others. As the profession struggle with its stance on the architecture role in incarceration, I believe that it is important to engage in such project. By taking part in the design of these facilities, architects can put to good use their knowledge on creating spaces for the betterment of people. Participating in design completion of detention center will help find better solution to the influx and overcrowding crisis going on in today’s detention centers. Architects need to stop ignoring detention centers as this behavior won’t solve the issue, and their absence and silence is complicit in refugees suffering.

Conclusion

Turning a blind eye on the history of marginalization of refugees in the United states detention center is common and perpetuating oppression. The story of the journey of Haitian immigrants highlights the double environmental injustice that they face. One in their country, where they are forced by climate change to emigrate, and secondly upon their arrival to what they think is a “promise land”. The perilous journey for many isn’t worth the treatment and refusal constantly inflicted by the United States, which grandly contributes to them leaving Haïti by being the second contributor of greenhouse gas to the earth’s atmosphere. Upon arrival many refugees are placed in these non punitive temporary facilities that jeopardize their human rights and dignity as they experience toxic exposure to chemical disinfectant, inadequate medical responses, sanitation and hygiene issues name a few. These experiences are mostly due to the overcrowding of these facilities operated and designed by private companies that prioritize profit over people’s lives. The reticence of the architectural profession to design these facilities has led to other professionals like businessmen to oversee the execution of the design intents. The America land of opportunity and hope propaganda clearly ceased in the early 2000’s but the message of it now being the land of horror and oppression has yet to reach many.

Keywords

Climate change, Displacement, Immigration, Refugee, Infrastructure, Building systems, Built environment, Architecture, United State of America, Haïti, Haitians, Detention Centers, Migration, Borders, Injustice.

Endnotes

1 “Global Estimates 2015: People Displaced by Disasters.” IDMC. 01 July 2015. Web. 10 Dec. 2020. <https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/global-estimates-2015-people-displaced-by-disasters>.

2 Olsen-Medina, Kira, and Jeanne Batalova. “Haitian Immigrants in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.org. 22 Oct. 2020. Web. Nov. 2020.

3 Batalova,Jeanne, and Chiamaka Nwosu. “Haitian Immigrants in the United States in 2012.” Migrationpolicy.org. 20 July 2020. Web. 08 Dec. 2020. <https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haitian-immigrants-united-states-2012>.

4 Gavigan, Patrick. “Migration Emergencies and Human Rights in Haïti.” Migration Emergencies and Human Rights in Haiti. Conference on Regional Responses to Forced Migration in Central America and the Caribbean, Oct. 1997. Web. 4 Dec. 2020. <http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/gavigane.html>.

5 Beveridge, Andrew.Unpublished Report on Haitians in the US. Queens, NY: Sociology Department, Queens College, CUNY. 1996.

6 Preeg, Ernest H. The Haitian Dilemma: A Case Study in Demographics , Development, and US Foreign Policy. Washington, DC: The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). 1992.

7 “Haiti Profile – Timeline.” BBC News. BBC, 11 Feb. 2019. Web. 5 Nov. 2020. <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19548814>.

8 Schulz, Jennifer, and Batalova, Jeanne. “Haitian Immigrants in the United States in 2015.” Migrationpolicy.org. 16 July 2020. Web. 2 Dec. 2020. <https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haitian-immigrants-united-states-2015>.

9 “Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, 11 Sept. 2020. Web. 22 Oct. 2020. <https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks>.

10 Charles, Jacqueline. “New Migration: Haitians Carve a Dangerous 7,000-mile Path to the U.S.” Miamiherald. Miami Herald, 24 Sept. 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2020. <https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/haiti/article103920086.html>.

11 “Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001).” Justia Law. Oct. 2000. Web. 1 Dec. 2020. <https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/533/678/>.

12 Roldan, Riane. “Lawyer: Inside an Immigrant Detention Center in South Texas, “basic Hygiene Just Doesn’t Exist”.” The Texas Tribune. The Texas Tribune, 23 June 2019. Web. 16 Oct. 2020. <https://www.texastribune.org/2019/06/23/immigrant-detention-center-mcalllen-overcrowded-filthy-conditions/>.

13 Admin. “Expose & Close.” Detention Watch Network. 02 Mar. 2016. Web. 18 Oct. 2020. <https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/pressroom/reports/2012/expose-and-close>.

14 “Immigration Detention Map.” Freedom for Immigrants. Web. 21 Oct. 2020. <https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/map>.

15 Gruberg, Sharita, and Tom Jawetz. “How the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Can End Its Reliance on Private Prisons.” Center for American Progress. 14 Sept. 2016. Web. 3 Dec. 2020. <https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2016/09/14/144160/how-the-u-s-department-of-homeland-security-can-end-its-reliance-on-private-prisons/>.

16 Joung, Madeleine. “What Is Happening at Migrant Detention Centers? What to Know.” Time. Time, 12 July 2019. Web. 3 Oct. 2020. <https://time.com/5623148/migrant-detention-centers-conditions/>.

Primary Sources:

Source 1

https://time.com/5623148/migrant-detention-centers-conditions/?playlistVideoId=5798848719001

This is a video of immigrants in an ICE detention center in McAllen Texas. I plan on analyzing this footage and compare it with the design intent in the “Detention Facility Design Standards for Immigration and Customs Enforcement” that I’m using as my secondary source.

Source 2

Semple, Kirk. “Haitians, After Perilous Journey, Find Door to U.S. Abruptly Shut.” The New York Times, September 23, 2016. https://nyti.ms/2cYkXrL.

This source is important as I’m analyzing the Haitian immigrant journey for the past 50 years. I’m trying to look at immigration numbers and patterns in the 80’s; 2000’s, 2010’s and 2020 to make a comparison. This is was written in 2016 and talks about a 7,000 mile journey from Haiti to Brazil in 2010, then through 11 countries from South America to Central America to reach the United States.

Source 3

Fjellman, Stephen M., and Hugh Gladwin. “Haitian Family Patterns of Migration to South Florida.” Human Organization 44, no. 4 (1985): 301-12. Accessed October, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44126263.

This source is important as I’m analyzing the Haitian immigrant journey for the past 50 years. I’m trying to look at immigration numbers and patterns in the 80’s; 2000’s, 2010’s and 2020 to make a comparison. This is was written in 1985 and talks about the journey from Haiti to south Florida

Source 4

Stepick, Alex. “Haitian Boat People: A Study in the Conflicting Forces Shaping U.S. Immigration Policy.” Law and Contemporary Problems 45, no. 2 (1982): 163-96. Accessed October, 2020. doi:10.2307/1191407.

This source is important as I’m analyzing the Haitian immigrant journey for the past 50 years. I’m trying to look at immigration numbers and patterns in the 80’s; 2000’s, 2010’s and 2020 to make a comparison. This is was written in 1982 and is following the stories of different experiences of boat people. ing both their presence in the United States and their claims for political asylum.

Source 5

Saadi, Altaf, Maria-Elena de trinad Young, Caitlin Patler, Jeremias Leonel Estrada, and Homer Venters. “Understanding US Immigration Detention: Reaffirming Rights and Addressing Social-Structural Determinants of Health.” Health and Human Rights 22, no. 1 (2020): 187-98. Accessed October, 2020. doi:10.2307/26923485.

This source is looking at mass immigration detention existing in the United States and how it mimics the criminal incarceration system and holds detained individuals in punitive, prison-like conditions. This source will be helpful when I’m exploring the point of being a climate chage refugee makes you a criminal.

Source 6

Countries of Birth for U.S. Immigrants, 1960- Present graph. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrants-countries-birth-over-time?width=1000&height=850&iframe=true

This graph was helpful in identifying the periods of the Haitian immigration journey that I could analyze and showed how between 2010 and 2020 the number of Haitian immigrant grew at a faster paste which led me to make other researches. I think this graph can be used in my paper.

Source 7

Migration in a controlled flow through Panama by Cronkite News. 19 Jul, 2020 https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/3216587/?utm_source=showcase&utm_campaign=visualisation/3216587

This map and data was important in understanding why there were so many Haitian immigrants in Texas and where they were coming from. This might be used a secondary source.

Source 8

Chak, Tings. Undocumented: the Architecture of Migrant Detention. Amsterdam/ Montreal: Sections, 2014.

I’m working on getting access to this book, it is more of an illustration, but from the snippets that what I’ve seen, it has axonometric drawings, floor plans, and spacial composition of a detention center in Canada. It is strong on the illustration side, but I’m mostly interested in looking at the architectural drawings. It can be useful for when I’m analyzing the build environment of the detention centers and how I can represent and explain them.

A few pages can be found on the author’s website: https://tingschak.com/undocumented-the-architecture-of-migrant-detention

An excerpt :http://www.scapegoatjournal.org/docs/07/SG07_165-182_TingsChak.pdf

Or a video of the flip through can be seen: https://www.ideabooks.nl/architecture-landscape/9789492058003-undocumented-the-architecture-of-migrant-detention

Source 9

Pacheco, Antonio. “Why Are Architecture’s Major Professional Organizations Silent on the Immigrant Detention Debate?” The Architect’s Newspaper, June 29, 2018. https://www.archpaper.com/2018/06/architecture-profession-silent-immigrant-detention-system/.

I’ve been looking at a lot of articles published in the last four years, to be informed of the Architectural profession on detention centers. This article highlights different voices from different architecture associations in the USA and their stance on the subject. I intent on using it as a source to help frame and understand who builds these facilities if architects refuse to do so.

Source 10

Craig, Nathan, and Margaret Brown Vega. Rep. “Why Doesn’t Anyone Investigate This Place?”: Complaints Made by Migrants Detained at the Otero County Processing Center, Chaparral, NM Compared to Department of Homeland Security Inspections and Reports. Detained Migrant Solidarity Committee (DMSC) and Freedom for Immigrants (FFI), July 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a33042eb078691c386e7bce/t/5b4c2f0b88251b376ed2d8fb/1531719451809/Otero+Report+Final.pdf.

This report analyses many issues like “Inadequate and Poor Quality Food, Inadequate Medical Attention, Labor Exploitation, Unsanitary Conditions, Limited Outdoor Access, Inadequate Access to Legal Resources, Immigration Detention as a Private Industry…” and other at the Otero County U.S. department of Homeland Security in El Paso. This is a great resource that I can use when analyzing conditions in detention centers. The different sections in this report bring me a lot of knowledge and I plan on heavily using it to showcase the environment injustices happening in detention centers.

Secondary Sources:

Source 1

Freedom for Immigrants. “Interactive Map – U.S. Immigration Detention.” November 6, 2017. Map. Freedom for Immigrants. https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/map. https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/map (Links to an external site.)

This map is very informative as it helps me identify not only to location of the immigration centers in the US but different informations like abusive unit placements, toxic exposure to chemical disinfectant, inadequate medical responses, sanitation and hygiene issues, facilities with COVID-19 etc. This information helps me with narrowing down the detention centers that I was to focus my research on.

Source 2

Wah, Tatiana, and François Pierre-Louis. “Evolution of Haitian Immigrant Organizations & Community Development in New York City.” Journal of Haitian Studies 10, no. 1 (2004): 146-64. Accessed October 7, 2020.

The first few pages of this journal article help me with the history of Haïtian immigration trends to the US. It is useful when thinking of how we got to having more Haïtian families in detention in 2020.

Source 3

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Office of Detention and Removal Operations, Contract Detention Facility Design Standards for Immigration and Customs Enforcement § (2007).

This design standard of detention center shows me the built environment of detention center. It helps me understand the proximity of spaces and the general idea/ concept behind those facilities. Bubble diagrams and description show the may idea, and a few photograph and plans help concretize the space in an architectural language. When reading stories of injustice, it’ll help me better conceptualize the space.

Source 4

Lindskoog, Carl. Detain and Punish: Haitian Refugees and the Rise of the World’s Largest Immigration Detention System. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018. Accessed October 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvx076dx.

This book is being analyzed as a possible inspiration for writing the different stories of Haïtian that found themselves in detention centers from 1973 to 2000. the story telling style will help when I’ll be re-tracing an Haïtian’s immigrant’s journey.

Source 5

Tabak, Shana. “Refugee Detention as a Violation of International Law.” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) 110 (2016): 215-18. Accessed October 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/26420197.

This is used to inform myself of the different international laws and human rights that the detention centers might be violating.

Source 6

Lennox, Malissia. “Refugees, Racism, and Reparations: A Critique of the United States’ Haitian Immigration Policy.” Stanford Law Review 45, no. 3 (1993): 687-724. Accessed October 7, 2020. doi:10.2307/1229010.

Although this article was published in 1993, it analyzes the US immigration system towards Haïtians which is the population that I’m focusing on. This is used as a general informational piece to make sure that I’m aware of all the possible angles when undertaking this topic.

Image Analysis:

The selected image is a picture taken in 2014 by John Moore in a detention facility in McAllen, Texas. Moore has been able to capture many scenes inside of the United States detention centers, which haven’t been accessible to many. His pictures gives a rare insight at the interior look of most recent detention centers, which helps understands people’s treatment whiten them. The built environment of detention centers weren’t supposed to be prisons adjacent nor supposed to criminalized populations fleeing climate change or humanitarian crises, but despite their intent to be safe temporary transitional spaces, many would argue the contrary.

This particular picture was chosen, because of the clear overview of the built environment of this particular detention centers. Due to the influx of immigrants, most of Moore’s pictures are usually filled with people; but the lack of people in this photograph give a clear sight of the components that composes the space.

The perimeter load bearing CMU walls, provide an open space with little obstruction, which is ideal for sight. To keep consistent with the importance of sight, the separated space are made of chain-link fences which does not interrupt one’s vision and is ideal for supervision. Adding to the need of sight, a concave mirror is installed at the top of the fence, where a right angle corner is formed. Having a warehouse like open space, also allows for flexibility of reduction of expansion of spaces if needed. This allows them to accommodate more or less immigrants depending on the demand.

Assuming that the guard in the picture if six feet tall, the chain-link fences around the facility, seem to be at least twice as high which would discourage anyone from climbing them. The door that allows access to the different sections, is also equipped with a number pad, which indicates that not everyone can move freely from one space to another. Only those provided an access code can.

There are no windows in the perimeter walls nor skylights, instead bright white lights are suspended from the ceiling. The idea of not having any fenestration, seems to be intentional, as not having sight of the outside can remove one’s sense of time and location.

All of the previously mentioned components of the picture, if not given the location and context, would easily be identified as a jail.

Another important aspect of the picture, the human aspect, helps understand what kind of people are found in these spaces, and how they are being used.

At the center of the picture, a young child is found looking up at a television screen, where casper the friendly ghost is being played. The television is mounted on a plywood board, which indicates that it was a last minute thought, as wood isn’t found anywhere else in the facility. The child is performing a “child like” activity but now in a child like place, as there are no place to seat and he his standing up to be entertained. Another striking element of this child is his feet; he isn’t wearing any shoes, which invoke two thing: that he can’t go too far and that the place that he is in, is more of a long term space for him to occupy, which is in contrast with the guard wearing an uniform and shoes, which is a temporary condition.

Other than the guard’s uniform, his posture and sight bring a lot of enigma to the picture. Although he is standing next to the child and his body is facing the camera, He isn’t looking at the photographer nor the child. Instead he seems preoccupied by something happening outside of the picture frame and has a grip around his belt, which could possibly be a gun.

This image by Moore shows the kind buildings and treatments that refugees experience when being in “detention” from fleeing climate and humanitarian crises that they had no partake in.