“Take the Lane vs. Thanks for the Lane”, the Economics, Politics and Health Inequalities of Bicycle Infrastructure in Newark and New York, 1980-2015

by C.W. Sleasman

Site Description:

Prior to the ubiquity of the automobile in Newark and Manhattan, the bicycle was seen as a brilliant mode of transportation by those who adopted the machine into their lives. Early cyclists of both cities came together in order to create better riding conditions for themselves and in the process contributed greatly to early bicycle and pedestrian centered infrastructure solutions that also provided escape from turn of the century emissions and pollution. Despite massive infrastructure upheavals, political pushback and the dominance of the car, the bicycle managed to leave a lasting impression within Manhattan while in Newark it was sidelined and brushed into the dustbin of history. This project seeks to find out why that happened and what consequences have arisen from the environmental inequalities that have developed since. As we shall see, the development of infrastructure in cities is dependent on decisions that have economic, political and health consequences for their citizens. Lastly, by understanding the successes that have transformed the pedestrian and cycling accessibility of New York City, I will provide commentary on what Newark can do and has done to improve these areas of infrastructure for their citizens.

The two videos below illustrate the current inequality of cycling infrastructure in Newark (video 1) vs. New York City (video 2).

Introduction: “Take the Lane” vs “Thanks for the Lane”

Tuesday, April 8th, 2024, bellowing truck after bellowing truck ripped by as I rode my bicycle through another set of skeleton rattling potholes in the road. “Oh, my god! I swear it’s like riding on the surface of the moon!” This ain’t the first time this surly comparison between the quality of a dangerous road and my presumption of what the gnarled surface of our planet’s dance partner must be like. The accompanying strategy to offset cars getting too close is to just “take the lane.” It’s the kind of wisdom that embodies the required self-preservation needed to survive riding a bike in Newark. Cars play it fast and loose with New Jersey’s seminal 2022 law requiring four feet of passing space and they rush by but a fist bump’s width away1. For all the hazarding I put myself through just to ride my bike here, just twenty miles away in Manhattan, successful policy achievements in bicycle infrastructure made the city a mecca for bicycles.

A week later, I was blessed with the sort of weather that pulls everyone out of doors and into the Manhattan streets. Taking my favorite bicycle, I joined in rambling down New York City’s first “protected lane”, Ninth Avenue. Established in 2007, it’s become such a well-trodden ribbon of tarmac its notable green paint has slowly faded from constant use2. I ease by dozens of other happy riders. I sprint through reds when traffic rhythms hit a rest note. I found myself dispensing with “taking the lane” and instead, brimmed with a gratitude that translated to being, “thankful for the lane.”

This ride and the accompanying atmosphere of a protected bike lane nestled away from cars, was so opposite to my experiences in Newark. Why, when thinking about infrastructure in Newark, was I ever in a position where I had to fear for my life when I’m just trying to ride my bike and why was my experience in Manhattan so different? What do these infrastructure failures in Newark and successes in New York, when examined comparatively, mean? How did this happen? What are health consequences of riding in a place like Newark, especially on roads where one is more exposed to harmful particulates, and the dangerous fumes of industry?

Historians have covered many aspects of Newark. Its foundation, its early success as an industrial city, its famed history for being acutely a part of the “golden era” of American cycling and why it’s now considered one, “the worst city in America.”3 Newark is New Jersey’s largest, most densely congested city where bicycle infrastructure does not or barely exist. Historians and scholars have also covered Manhattan and the bicycle’s deep relationship to the city as well. However, a comparative analysis of these two cities’ commitment to improving bicycle infrastructure and subsequently improving their citizens’ health has not been done yet. I argue that the policy failures of Newark and the policy successes of New York City with regards to bicycle infrastructure have had direct effects on economic, political and health inequalities for their citizens.

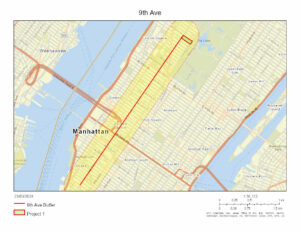

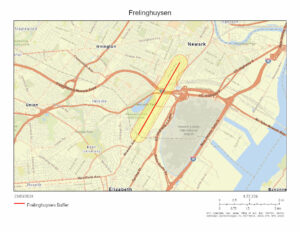

To do this, first we need to analyze the early history of Newark and Manhattan and their relationships to the bicycle. To cover this, we must understand how the respective politics of the time worked, how their economies functioned, and the resulting fluctuations in health that followed. Following that analysis, I will explore these results by weaving together a contemporary history of the cities between 1980-2015. I will analyze a section of road from both Newark and Manhattan (Frelinghuysen Avenue and Ninth Avenue, respectively) and touch on how infrastructure improvements that are geared towards pedestrians and cyclists are key to healing cityscapes. In doing this, I am willingly investing in the hope that if the time comes that Newark and its citizens are presented with an opportunity to invest more heavily into not just bicycle infrastructure but what it represents, which is a greater pedestrian and citizen experience of their urban environment, it can be done with the aid of history, economics, politics and health.

Pre-1980s: Newark’s Golden Age of Cycling

At the zenith of Newark’s late 19th and early 20th century industrial capabilities, “Arguably no other U.S. city was so closely associated with industry and manufacturing. Newark ranked third in terms of overall industrial output, despite its comparatively small population, ranked thirteenth in the country.”4 This manufacturing output became instrumental in creating infrastructure conditions that allowed not just the bicycle to flourish but for individual and collective mobility to flourish along with it. As Michael C. Gabriele uncovers in his book, The Golden Age of Cycling in New Jersey, Newark in the 1880s and 1890s, “was a vibrant center for manufacturing bicycle components.”5Newark’s booming industrial economy helped paved the way – literally, for better roads.

Bicycle enthusiasts at this time largely came from the upper echelons of society where their political demands would be met with little resistance, “The first bicycle clubs, which formed in the late 1870s, may have been upper-crusty fraternities for racing and socializing, but they quickly developed a political agenda.”6 Demanding better conditions led to greater organization and so, “a national organization founded in 1880, the League of American Wheelmen, (LAW), sought to make the country safer for wheeling”7 and these demands were resoundingly met by farmers who also were seeking better road infrastructure in order to be able to transport their goods into Newark. When it rained, much of the roads that led from these farms to the outside world became muddied, rutted – making transport more difficult and cycling much more challenging. Newark began to boast the finest “macadam” highways, early versions of paved roads created by layering compacted stone bounded together with tar or asphalt by the late 1880s, “By the turn of the century, a new and powerful voice had been added to the clamor for still better roads. In addition to the farm-to-market group, the large membership of bicycle clubs became a demanding factor. They needed hard-surfaced roads to accommodate their activities.

The answer was an increase in the number of roads surfaced with water-bound macadam, and, by 1830, macadam became the popular type of construction material”8. Slowly, consistently the road conditions of Newark improved alongside a budding cycling community so much so that a 1894 edition of the New York Times took note stating: “New Jersey has one of the finest road systems of any state in the Union, and probably no two counties in any State offer such facilities as do Essex and Union.”9

Before long, Newark became world-renowned for their velodromes and their roads. In Michael C. Gabriele’s, The Golden Age of Bicycle Racing in New Jersey, an Australian native by the name of Alf Goulett gave an account in 1980 of his racing days in the early 20th century saying, “They said if I felt I was really good, I had to go to Newark and measure myself against the best in the world.”10

The creation of better roads led to an ease in mobility which allowed larger groups of cyclists to leave the city in search of areas where the emissions from Newark’s factories would not affect them. “The route of the run after leaving this city was through the following towns and cities: Belleville, Montclair, Millburn, Elizabeth, Westfield, Plain Field, New Brunswick, Old Bridge, Matteawan, Red Bank, Seabright, Long Branch and Asbury Park.”11In these towns, cyclists would find themselves free of the city air, in a more pleasurable environment where greenery and rolling hills met their tenacity for “wheeling”.

Newark’s industrial economy, politically active hobbyist clubs alongside a growing competitive scene, and their ability to cycle to reaches of New Jersey where environmental effects of industry could not harm as significantly are all a part of Newark’s early history with regards to bicycle infrastructure. It pains me to see how the contemporary reality of the city gives the bicycle almost no quarter. I was shocked to read old newspapers from this era. All I have ever heard of Newark was how congested, foul and dangerous the area was. To think that bicycles wheeled freely along wide roads to greater parts of New Jersey filled me with a kind of nostalgia I have no part in and a terrible sadness for what could have been.

Pre 1980s: The Bicycle and New York City – Problems, Popularity and Potential

On the other side of the Hudson River, bicycles were challenging the status quo of New York City. The city was going through a time of upheaval, mass immigration was creating racial tensions, disparities in wealth were widening daily, and alongside disease epidemics like Cholera that were fomenting in the streets, bicycles wheeled to the consternation of many.

The arrival of bicycles in Manhattan was not without a reaction of rancor. Its predecessor the velocipede was banned within the first three months of it wheeling about. Lawmakers enacted this ban largely in response to where these early bicycles were being ridden, in the parks and on the sidewalks. The roadways of early Manhattan were all but cobblestone streets or muddy dirt roads that became rutted and difficult to maneuver in when the rain came. By the late 1800s, the velocipede had evolved into what we would consider the early bicycle and with this evolution came a greater debate about where they could be ridden and if they were a mode of transport.

The debate was not just local to Manhattan but was expanding across the river to Jersey City and Newark where, “lawmakers agreed to let velocipedes wheel through the streets but banned them from the sidewalks.”12By this point in the bicycle’s history formal groups and bicycle clubs had begun to become politically motivated enough to fight for the rights of not just riders but of helping develop infrastructure so that they could enjoy the use of their machines, “several bicycle clubs that formed part of an emerging bike lobby.”13 These clubs promoted the bicycle as a tool, placing it as an idea that allowed for expression but importantly, to show the limits with regards to infrastructure that New York was sown in by. Furthermore, as Evan Friss writes in his book, On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York, that it was the belief of cyclists that it was, “a democratizing and Americanizing force” (p. 45). Just as in Newark, where cyclists were clamoring for macadam roadways, so too in New York were they calling for “asphalt ribbons.”14These small improvements to infrastructure accounted for just a narrow strip laid overtop the road since paving the road was deemed too expensive. As these improvements to infrastructure continued so did the ability for cycling New Yorkers to abscond the diseases that were brooding in the streets and free themselves of the weight of urban industrial emissions.

With the bicycle’s introduction to Manhattan, doctors placed a high value on the tonic of being able to ride away from the city’s smallpox, yellow fever and cholera outbreaks of the 1800s, “New Yorkers on wheels could “fly from infection” and infectious sufferers. The velocipede would be the hero to finally defeat the city’s dark side.”15The bicycle and its ancestor the velocipede allowed New Yorkers ease of access to the ocean breezes of the Atlantic where the fumes of industry, the miasma of disease and noise of urban life were quieted, “It was in New York-big, dense, chaotic-where bicycles appeared in the greatest numbers and where they seemed to offer the greatest promise: of faster commutes, healthier bodies, a cleaner city, richer social opportunities, independence from streetcars, and the freedom to roam.”16 In the search for healthier bodies, many New Yorkers found themselves cycling out to the salty brine of the ocean at Coney Island. “The Coney Island Cycle Path set off a wave of bike path building around the country.”17This became such a popular way of reorienting the cardiovascular health of New Yorkers that it became one of the first instances of bicycle infrastructure in the city as a bike path that went along Ocean Parkway.

The value that the bicycle had to New Yorkers who adopted them into their lives was immense. This value reoriented how these citizens viewed their city and how they felt it could best serve them. By using the bicycle as a driving force against pushback from the law riders wielded the economy, politics, and their health in their favor and established bicycling in New York as a way of life. While the bicycle industry would go through a number of booms and busts throughout the next century and a half, bicycling created a way of life that was well preserved in New York despite pushback, the mass adoption of the automobile, the continued growth of the subway system and drastic infrastructure changes by Robert Moses. With regards to bicycle infrastructure and the growth of car dependence in the city, Robert Moses’ role cannot be overstated enough. His transformation of New York City has had fundamental repercussions on pedestrian and cycling infrastructure and the very lives of nearly every citizen within the city.18

As we shall see, Newark for all its competitive glory, its history of bicycle parts manufacturing and ease of access to greater parts of New Jersey would suffer as bicycle advocacy in the city diminished with changing demographics, political corruption, consequences of structural racism and infrastructure developments that mired the city in festering racial tensions that would continue to color “Brick City” for most of modern history.

1980-2015 Newark: “The Worst City in America”

By 1980, Newark was a tired city. Brad Tuttle’s, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City covers this succinctly stating that, “None fared worse than Newark. The city seemed to have fallen apart even more quickly than it had skyrocketed to riches and industrial prominence a century before” (p, 208). Decades of white flight, redlining, the mass development of low-income housing, systemic political corruption, racial violence, the subsequent riots that followed in 1967, alongside the domination of cars by way of multiple highways cutting through and around the city had transformed what was once a vibrant, diverse, hopeful metropolis into what was deemed, “The Worst City in America.”19 By 1980, the car had long outpaced the bicycle in terms of convenience, ubiquity, and infrastructure, “private homeowners hadn’t faired much better. Thousands of houses were destroyed to make way for I-78 and various urban-renewal projects.”20The macadam of highways of old had been replaced by asphalt that daily thousands of cars would drive through. The infrastructure development that gave the automobile superiority in Newark also came at the cost of available pedestrian and cycling space with city having, “the least acreage of public parks per resident just four feet by four feet for each Newarker as well as the lowest percentage of amusement and recreation spots per person.”21Emissions hang like dirty wreaths upon the city and its citizens. The cyclists that were once an affluent and politically motivated and capable bunch had long since moved away, or had died off, and the mantle of their cause was taken up by others but in suburbs where they felt safe and at a distance from the city. In this a bitterness would arise out of Newark’s veteran cyclists, “Specific complaints were that the power brokers of the golden age lacked the vision to invest in the game and innovate and failed to develop a new generation of talent.”22 During the 70s and 80s, cities all over the country were crushed by white flight, redlining policies and urban decay. As a result of the vibrant economy of Newark filtering out to the suburbs, the political incentives of cyclists who formerly were fighting for better road and infrastructure equality in the city dissipated. With this, concerns for health and the effect of emissions were forgotten as these concerns were massaged by the openness of suburban living. This left Newark’s bicycle infrastructure to falter in the wake of the automobile.

The results of these historical contingencies and infrastructure policies were that citizens of Newark were the ones who were going to suffer with the consequences of environmental inequality. Newark’s policies and lack of funding slowly began to eat away at what makes cities livable. The fact that it is an international hub of import and export means that heavy duty vehicles such as semi-trucks, shipping vessels that can handle hundreds of containers, and planes are going to be heavily in use within a small area. Again, to quote Tuttle, “The city was simply too valuable a hub for transportation and commerce to remain tangled in despair and economic malaise forever” (p, 210). When I took my bike and rode about “Brick City” and more specifically to ride the length of Frelinghuysen Avenue to record it for this project I could see and feel the physical effects of “the value” Newark had as a hub. Using data from EJ Screen we can see the amount of diesel particulate matter that is endemic to this area. Frelinghuysen Avenue is a heavily trafficked road. Large trucks carrying the imports and exports of the world drive overtop tarmac in consistent earnest. The fumes and emissions they set loose are then inhaled daily by the residents of this area. At one intersection specifically, Frelinghuysen Ave and Meeker, members of the South Ward Environmental Alliance and residents of the area counted more than 416 “garbage trucks, buses, car carriers, and tractor-trailers.”23

Using the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJ screen tool which provides access to demographic and environmental data the effects of living near heavily trafficked economic zones can be shown. EJ Screen was used both for Ninth Avenue and Frelinghuysen Avenue to provide a comparative analysis of two areas. Frelinghuysen Avenue, which in a previous time in history was the cyclist’s highway for leaving Newark, has now transformed into a heavily trucked road where no infrastructure safety exists for cyclists and barely any exists for pedestrians living in the area. The parameters I chose was the length of Frelinghuysen Avenue beginning at the corner of Sherman Avenue and Astor Street and then running the length of its entirety before it turns into Newark Avenue. I then placed a quarter mile wide buffer on either side as seen above. 24Residents of this area are at a high risk of respiratory toxins such as diesel particulates are in the 89th percentile in the state of New Jersey. Traffic proximity (calculated as daily traffic count/distance to road) is at a value of 400, whereas the state average is 210. With the state average of 9.5% for asthma this region surrounding Frelinghuysen Avenue sees residents with a 12.2% average for asthma. During my ride down this road, I was overcome by an industrial smelling stench that filled my nostrils and made me apprehensive to draw deeper breaths.

The absurdity of riding a bicycle here finally came to a head when as I was riding by someone on talking on their phone they quite literally said, “Oh my god. That man is riding in the street?!” A very far cry from once what was and a world away from what could be. I just thought to myself if my mind was blown that this was once a place so highly regarded to ride a bike then what would that guy have thought? There’s no way he’d believe it. That is how powerful the recent history of Newark is.

1980-2015 New York City: The Bicycle Renaissance and its Future

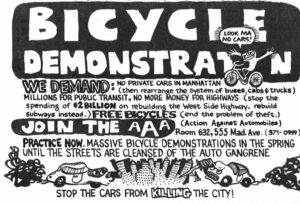

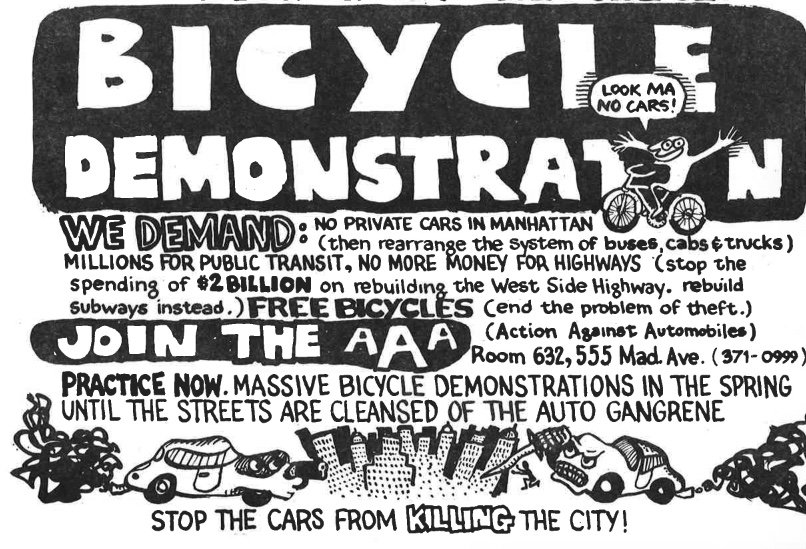

New York City from 1980 to 2015 saw a renaissance in bicycle advocacy and use that bloomed out from the ashes of the same sort of urban decay that had melted away most of the success of Newark. The 1970s saw a resurgence in bicycling as a response to multiple oil embargos and economic stagflation. Multiple organizations and clubs remained in New York City and maintained the political consciousness cyclists required in the face of bicycle bans and the increasing presence of emissions and cars, “Then there were the Bicycle Commuters of New York, The New York Cycle Club, the Staten Island Bicycling Association, and the Bring Back the Bicycle Committee, whose title was a reminder that bicycles were once and could again be a major force in the city” (Friss, 114). As the presence of cars continued to tick upwards over the years since its introduction to the city the bicycle was more and more maligned and pushed aside. Often, the bicycle was seen as a toy or a nuisance, the growth of minorities using bicycles for work and to commute meant that now there was a racial element to the adoption of the bicycle. Although, these minorities use of the bicycle was largely due to economic and infrastructure constraints that “city life” imposed on them. This led to political developments such as the AAA (Action Against Automobiles) which demanded better and fairer use of tax money to benefit pedestrians and cyclists over cars. 25

Community action and protests in the form of “Bike-Ins” where thousands of cyclists would ride through Manhattan streets in protest the hostile manner car centric infrastructure had created were the beginnings of a modern, urban advocacy to place the bicycle back in the forefront of transportation modes. In the mid 80s, Mayor Koch enacted a bicycle ban in Midtown Manhattan much to the ire of bicycle messengers who made much of their income I that area. This ban had the catalyzing effect of bringing bicycle advocacy to the forefront of political discussions in the city. Cyclists once again were trying to convince city officials, citizens and pedestrians that they had as much of a right to be on the roads as cars did and in fact had a historical preeminence to that right that the automobile did not. The bike ban was eventually repealed in 1987 and paved the way for a renaissance in bicycle use in the city. Slowly but surely, redevelopment and reconsiderations of the bicycle’s power with regards to ease of access continued to grow.

While Giuliani started the improvements in pedestrian spaces (as a means to bring back the economic power of local businesses) which more or less coalesced around the idea of redesigning physical spaces to exert urban social control so that tourists and middle- and upper-class individuals could move safely. It was the election of Michael Bloomberg as the new mayor of New York City that kicked off a renaissance in bicycle infrastructure development. As a part of his PlaNYC: A Greener, Greater New York, Bloomberg sought to create a new version of New York City that saw investment in climate change resiliency as 26part of an overall strategy to reorient the city as an economic powerhouse. Bicycle advocacy and bicycle infrastructure were a core part of this development. The employment of Sadik-Khan has his head of Department of Transportation jump started a rapid pace in implementing bicycle infrastructure. The Ninth Avenue bicycle lane was the first protected bicycle lane in Manhattan and was inspired by bicycle infrastructure from the Netherlands where advocates for the kind of climate policy that Bloomberg was attempting to implement were already way ahead of developing. The transformation of Ninth Avenue began with siphoning off a lane for car traffic to make room for a protected bicycle lane on the left-hand side of the street. By doing this, you effectively have given cyclists a safer place to ride, while simultaneously slowing down and subtracting the amount of congestion points the avenue previously had. There are still large intersections (notably 23rd Street) that still find themselves burdened with the occasional gridlock but the regularity of that occurring dropped significantly – especially when larger integration of GPS applications came to the fore. What this did was create an extra vein of traffic that bicyclists could use with such regularity and confidence that at one point the bicycle lane’s success was determined by how many parents with their children on bikes were regularly using the lane. “But it did not take long for the DOT to judge the lane a success. Ninth Avenue attracted 63 percent more cyclists than before and managed to do so while reducing the number of crashes” (Friss, p. 158).

Conclusion: Takers and Thankers Revisted

Newark, “Brick City”, a place where, in order to get where one must go if you’re “crazy enough” to ride a bicycle, you are largely forced to “take the lane”, you are largely forced to place yourself within a calculus of fate that has been determined by a century of failure with regards to infrastructure. This is directly a result of policy failures within economic, political and health spheres that allowed the domination of infrastructure that benefitted cars chiefly over pedestrians and cyclists.

It’s a sad history that a city like Newark that was at one time, one of the shining beacons of industry, development and cycling that it would be maligned to be considered “one of the worst cities in America”. But this is what history is – a compounding force over time that directly results from decision and consequence. The initial introduction of the bicycle in Newark pushed road development forward. It allowed its residents to seek healthier spaces to breathe and gave them a new sport in which to compete and subsequently brought the city and New Jersey worldwide acclaim. The bicycle’s slow disintegration and eventual panning into the dustbin of history in the city was not a result of maliciousness but more one of economics, politics and health choices that saw its advocates move to the suburbs, that saw the razing of homes for interstates and car centric roads with little space to walk let alone ride and with that – health choices for cyclists were more easily sought in suburbs. The result was that advocacy for cycling and pedestrianism in Newark would naturally decline as the populations of those who cared dispersed. And yet, as I ride here – I only see potential amongst the danger. I thought the results of this project would give me a greater understanding of how one would go about enacting the sort of change Newark requires in order to achieve this but alas it has not. In order for cycling advocacy and strong bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure to occur there needs to be strong voices and political advocacy groups that force the issue daily. While Newark has bicycle clubs and an interest, the suburbs and outlying areas of New Jersey offer cyclists the sort of riding that is sought. Newark does not possess the variety in commuting that New York City does, nor does it possess the numbers in population or economic weight. However, it still has the potential. I only see areas and roads where improvement can be made.

New York City on the other hand, where bicycles were once heavily maligned as being toys, public nuisances, dangers to pedestrians, road furniture to the automobile has remained a staple of the city. The advocacy of bicycle groups within the city gave weight to the bicycle throughout its entire history even in the face of intense pushback by citizens and political operatives. It became a tool of gender revolution when women adopted them for their own needs, a tool for environmental revolution when those concerned about their lived environment and the natural environment took to the streets to demand for better conditions, it became a tool to show how improvements with regards to infrastructure could be made and it became a tool for the promotion of human dignity as hundreds of thousands of men, women and children daily use their bicycles within the city to get where they need to go. The economic, political and health successes of New York City that were hard fought by these bicycle advocacy groups gave New Yorkers increased earning potential, a voice in politics and better overall health as they rallied against industrial and automobile emissions.

When I see people riding their bicycles in the city, I am thankful for the lanes that those who preceded me in their enjoyment of this machine fought so hard to achieve. When I interact with customers who are afraid of riding in the bike lanes, or do not know totally where to go or how to get there, I always reassure them of how easy it is get around by bike in the city now. When the new bike maps of New York City hit the shelves of the shop I work in, every year there are newer and newer lanes, connecting the boroughs and improving the roads. The quality of life that bicycle infrastructure has helped instill in New York City is a testament of “what could be” in this country.

Endnotes

- N.J. Stat. § 39:4-92.4

- Evan Friss, On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 157

- Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City (New Brunswick, N.J, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009), 63

- Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City (New Brunswick, N.J, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009), 63.

- Michael C. Gabriele, The Golden Age of Bicycle Racing in New Jersey (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011), 37.

- Margaret Guroff, The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life, (University of Texas Press), 55.

- Ibid

- https://dspace.njstatelib.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/81b57a5c-35ac-4a22-86a8-a5cdab54db25/content

- “‘NEWARK’S ACTIVE CYCLISTS: A CITY SPECIALLY ADAPTED FOR WHEELING. MACADAM HIGHWAYS LEADING IN EVERY DIRECTION FURNISH REMARKABLE FACILITIES FOR LONG ROAD RUNS — FAVORITE ROUTES FOR BICYCLING TOURS OVER LEVEL ROADS — SOME OF THE CLUBS THAT ARE FLOURISHING AND RAPIDLY INCREASING IN MEMBERSHIP.’ .” New York Times, April 23, 1894, 13322 edition. “NEWARK’S ACTIVE CYCLISTS: A CITY SPECIALLY ADAPTED FOR WHEELING. MACADAM HIGHWAYS LEADING IN EVERY DIRECTION FURNISH REMARKABLE FACILITIES FOR LONG ROAD RUNS — FAVORITE ROUTES FOR BICYCLING TOURS OVER LEVEL ROADS — SOME OF THE CLUBS THAT ARE FLOURISHING AND RAPIDLY INCREASING IN MEMBERSHIP.” New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 23, 1894. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fnewarks-active-cyclists%2Fdocview%2F95216896%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

- Michael C. Gabriele, The Golden Age of Bicycle Racing in New Jersey (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011), 7

- “NEW JERSEY CENTURY RUN.: TWO HUNDRED RIDERS WHEEL FROM NEWARK TO ASBURY PARK.” New York Times (1857-1922), Sep 06, 1897.

- Evan Friss, On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 12

- Ibid, 45

- Ibid, 48

- Ibid 12-13

- Evan Friss, On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 46

- Ibid, 48

- Ibid, 48

- Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City (New Brunswick, N.J, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009, 208

- Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City (New Brunswick, N.J, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009, 213

- Ibid, 213

- Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of an American City (New Brunswick, N.J, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009, 219.

- https://newjerseymonitor.com/2022/08/25/residents-of-newark-track-trucks-to-highlight-air-pollution/

- Environmental Protection Agency, “EJ Screen: EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/

- achieve.curbed.com/2017/6/28/15886810/bike-transportation-cycling-urban-design-bike-boom

- Environmental Protection Agency, “EJ Screen: EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool, https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/

Primary Sources:

Primary Sources:

- https://www-jstor-org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/stable/j.ctvzcz5h4

Nye, Peter. 2020. Hearts of Lions : The History of American Bicycle Racing. Second edition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

This is an extensive source of bicycle racing in the US. It covers the beginning of bicycling in America starting as a craze and how it slowly evolved into a more organized sport. With the evolution of the sporting aspect of cycling, recreation and pedestrianism flourished. There’s a very relevant section in chapter 4, that details how prestigious it was to be racing in Newark, New Jersey and then a following section detailing the New York Madison Cycling Events (which is where the Madison Square Garden got its name). I will be using this as a historical callback to where cycling was at this time as it relates to what bicycling became from the 1980s to the 2010s within Newark and New York City.

2. “Newark Bike Plan 2014,” https://bikenewark.files.wordpress.com, accessed February 28, 2024, https://bikenewark.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/newarkbikeplan.pdf.

This bike plan for Newark from 2014 is a more modern source for the kind of infrastructure planning Newark is looking to do in regards to the implementation of lanes. Two of its core goals is to “provide access within ¼ miles of network for all residents” and “Identify links needed to connect low-traffic, low-stress routes”. It also notes “aspects” that make Newark “less bike friendly” such as aggressive drivers, “opposition from car dealers with regards to Cleveland Ave”, “focus on vehicular traffic during road design”. While directly implying that bicycle infrastructure failed because of cars is perhaps too much to say outright, much of Newark’s vehicular focus is tied up in a long history of housing struggles within Newark with regards to early 20th century white-flight, mid-century redlining, suburban expansion and the race riots in the 1960s.

3.1894, New York Times: https://www.proquest.com/docview/95216896?parentSessionId=TYMgMXNtG0%2FvJwi7Fw9laotq9pbqLG33zMrff6BXU3s%3D&pq-origsite=primo&accountid=13626&sourcetype=Historical%20Newspapers

Annotated version: Bibliography

“NEWARK’S ACTIVE CYCLISTS: A CITY SPECIALLY ADAPTED FOR WHEELING. MACADAM HIGHWAYS LEADING IN EVERY DIRECTION FURNISH REMARKABLE FACILITIES FOR LONG ROAD RUNS — FAVORITE ROUTES FOR BICYCLING TOURS OVER LEVEL ROADS — SOME OF THE CLUBS THAT ARE FLOURISHING AND RAPIDLY INCREASING IN MEMBERSHIP.” 1894.New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 23, 2. https://login.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fnewarks-active-cyclists%2Fdocview%2F95216896%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D13626.

This source shows that at one point in history late 19th, early 20th century – Newark was considered a city “specially adapted” for “wheeling” (now known as cycling). It’ll (hopefully) provide some historical context of the city prior to automobiles becoming the dominant fashion by which people get around. The way the highways were constructed gave people access to and from the city via bicycling. The article notes the varying routes starting on Clinton Ave and going through Irvington, Milburn, Springfield, Metutchen and New Brunswick. Going from Millburn you can get to Summit. This was at a time when cycling in the USA was growing in popularity. Varying Newark bicycle clubs were popular at this time with membership ranging in the 200s. The Macadam highways being pristine and smooth a hundred years ago obviously flies in the face of the lived experience of not just myself but many others.

4.“History of Bicycling in Parks : NYC Parks,” n.d https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/bicycling.

This source details cycling in New York City through the perspective of the park system. It details in-depth the ebb and flow of cycling popularity from the late 19th century to the 21st century and gives a good perspective on why cycling infrastructure was successfully managed and applied in New York City – especially when compared to Newark.

5.Zhang, Myles. “Interstate Highways (78 and 280) – Newark Changing,” May 1, 1970. https://newarkchanging.org/1970/interstate-highways/.

This source details the history of the interstate highways and how they affected Newark. Essentially creating in and out roads that precipitated and eventually gave away to white-flight and automobile dominance in the city. It details how Blacks were locked out of the real estate market via redlining and how Newark chose between affordable housing or building highways with a line of thinking that highway systems would clear away the slums (it didn’t). This source gives a unique insight into the political power struggle of Newark at that time and also provides evidence for what sort of reverberations this kind of urban policy has. Less affordable housing, more cars, denser and more car centric roadways would obviously equate to a city where building, maintaining or even thinking of real bicycle infrastructure wouldn’t be permissible. It’s a stark contrast to New York City (while NYC was building highways in the city – it was at least providing bicycle lanes as well – to an extent).

Secondary Sources:

- “NEW JERSEY CENTURY RUN.: TWO HUNDRED RIDERS WHEEL FROM NEWARK TO ASBURY PARK.” New York Times (1857-1922), Sep 06, 1897.

This is a newspaper column in the New York Times that provides some background and context with regards to the primary source (1). It is a racing event that was in its fifth year which shows how popular this was becoming in Newark, New Jersey. I’m using this source to highlight a point about Newark’s infrastructure before cars. The point being how dramatically it has changed since. “The route of the run after leaving this city was through the following towns and cities: Belleville, Montclair, Millburn, Elizabeth, Westfield, Plain Field, New Brunswick, Old Bridge, Matteawan, Red Bank, Seabright, Long Branch and Asbury Park”. To imagine doing this, the first thought would be, “But, what about the cars!?”

2.https://www.proquest.com/docview/2131385729/bookReader?accountid=13626&ppg=60&sourcetype=Books

Guroff, Margaret. The Mechanical Horse : How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016. Accessed March 13, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. (Chapter Four, “Paving the Way For Cars”.

A historical account detailing the history of the bicycle in American life. The chapter I have chosen explicitly out of this book details how bicycles paved the way for the automobile. The creation of these “macadam” road systems was partly due to the organization of bicycle clubs developing a political agenda that demanded public access to thoroughfares. The LAW (League of American Wheelmen) “sought to make the country safe for cycling”. Cyclists riding out in the country were aghast at the state of country roads and encouraged farmers to lobby in the interest of better roadways (as poor roads in agricultural communities would be their biggest expense). Cycling during the late 19th century was above all-else a rich man’s fad that managed to capture the imaginations of many people (inventors included). When the bubble burst, what was left were blue collar laborers using the bicycle to get to work and the industrialization of the automobile. Cycling imbued individuals with a desire for self-propelled, and self-owned means of transportation.

3. https://dspace.njstatelib.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10929/23969/t7641975.pdf?sequence=1

The Development of Transportation in New Jersey, “A Brief History”. 1975.

“By the turn of the century, a new and powerful voice had been added to the clamor for still better roads. In addition to the farm-to-market group, the large membership of bicycle clubs became a demanding factor. They needed hard-surfaced roads to accommodate their activities. The answer was an increase in the number of roads surfaced with water-bound macadam, and, by 1830, macadam became the popular type of construction material”. This “brochure” is full of good information on cycling presaging the highway system. Following World War I, the automobile became more popular and better roads and highways were required to meet demand. There was also an increase to get “get the farmer out of the mud”.

4. Curvin, Robert. Inside Newark : Decline, Rebellion, and the Search for Transformation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

This book details the history of Newark, chapters 1, 2 and 3 providing most of the legwork in terms of its early history and up until 1970. This secondary source is important when talking about how as a city, Newark has a near impossible task of separating itself from its own history in order to have a chance at flourishing in the future. Noted in the book is a quote from 1950, “Nobody actually lives in Newark”. This idea that Newark is essentially an island, where suburbanites commute into for work, commute around to get to their homes, townships and that Newark has nothing to offer outside of this is an important historical distinction to understand because prior to the “urban machine” failing and the epidemic of low income housing, Newark was a vibrant city, an American epicenter for competitive cycling on the East Coast, whose only real flaw comparatively was being nextdoor to New York City.

5. Levels, Annika. “Rethinking the Street: Politics, Processes, and Space of Pedestrian- and Bicycle-Friendly Street Transformations in New York and Berlin.” Order No. 27610118, Technische Universitaet Berlin (Germany), 2019.

An in-depth analysis on street and pedestrian design with an emphasis (starting on page 70) on New York City from the time of Michael Bloomberg’s mayoral terms. This is a quite extensive analysis that covers the varying teams and strategies behind New York City’s Department of Transportation and their efforts to “green New York City”. Concerted governmental efforts such as the World Class Streets program, the exhibition of New York City Streets Renaissance Campaign, Summer Streets Program and the Sustainable Streets Program were all essential governmental planning actions that proved extremely fruitful and absolutely changed the urban landscape in a way few other cities in the world have done. This is an especially important background to have when comparing Newark to New York City because the primary reason this was possible in NYC and not in Newark was the financial capital and investment New York City has historically been engendered with. A history that Newark has not seen in nearly a century.

Image Analysis:

This image was chosen as it is the beginning of modern activism with regards to bicycles, pedestrianism and the fight against the domination of the automobile in New York City. The drawn poster shows two cars with squiggly fumes billowing out of tailpipes to depict the dirty emissions cars have been bringing into such a dense and congested place as New York City. The car on the left as a gun in its hand holding the city hostage while the car on the right has a knife, underneath them, the tagline “Stop the cars from killing the city!” is presented boldly. An obvious call to what bicyclists believes these cars are doing and with good reason. Bicycle infrastructure in Manhattan in the 1970s was dismal and bicycles were often seen as a nuisance and a toy, unimportant and insignificant to something as refined and as easy to operate as a car.

While the bicycle had first claim to the roads of world, slowly but surely the automobile drove in and quickly elbowed out the bicycle. April 22nd, 1970, the United States celebrated the world’s first “Earth Day” arranged by Gaylord Nelson and varying environmentalist groups to bring attention to the corrupting forces industrial waste had done to the natural environment and the lived/urban environment (1). Funded by the A.A.A. (Action Against Automobiles) this poster from 1972, called, “Look Ma, No cars!” (2) is a direct result of the actions of Earth Day and calls for a New York City that is less congested, and free from automobiles responsible for harmful emissions. “Stop the cars from killing the city” is a call to how infrastructure demands for automobiles were taking precedent over bicyclists and the subways and was a call to improve responsible commuting. The AAA funded political and protest actions called, “Bike-Ins” where thousands of cyclists would ride in the streets to protest the domination of cars and the lopsided attention they received with regards to infrastructure. This was also a response to the notion that bicycles were dangerous in New York City. On page 133 in Evan Friss’, On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York City, is a wonderful reference to the “us vs them” mentality that was growing with regards to how pedestrians and automobile drivers felt about the bicycle, “Cyclists were about as likely to be stabbed to death while riding as they were t send a pedestrian to the morgue, and pedestrians had about as much reason to fear death by bicycle as death by falling air conditioner”(3). Over the next 15 years this growing animosity would lead to a bicycle ban in Midtown as a “solution”.

Footnotes:

- Neil Maher, Lecture 20: 1970s Environmentalism, accessed 2024

- “Look Ma, No Cars!” 1972 Poster from Action Against Automobiles, NYC

- On Bicycles: A 200 Year History of Cycling in New York City

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

Frelinghuysen Avenue from C.W. Sleasman’s Point of View via chest mounted GoPro. I was lucky in that the road was relatively uncongested for this time of day. But, viewers will notice the large amount of trucks and heavy duty vehicles that are regularly on this road. Viewers should also take notice of the road conditions, the manner in which vehicles use the road and the role that pedestrian infrastructure has in this area.

Ninth Avenue from C.W. Sleasman’s Point of View via chest mounted GoPro. A congested time of day with heavy amounts of traffic in the bike lane in the car lane, however, traffic moves along quite easily. Viewers should take note of the various infrastructure improvements that have made this avenue safer to ride from physical separations in terms of pedestrian islands, cars used as dividers between bike and car traffic and wide left turning lanes that give cars the ability to see cyclists. Viewers should also take notice of how pedestrians are acting.