Critical Mass: Uranium and Thorium Pollution at the Westinghouse Electric Lamp Pant in Bloomfield New Jersey

by Nicholas Skific

Site Description:

Westinghouse Lamp Plant, now nothing more than a partially empty lot with new construction being used to bring in revenue to the town of Bloomfield NJ, had a colorful history for the decades that the factory stood on the lot between Macarthur and Arlington Avenue. This site was the home of a uranium production line that created radioactive elements to help the US with the creation of the world’s first atomic bomb; it was also the home of negligent dumping of radioactive poisons into the city’s sewer system until its shutdown in 1986. In 2006 Bloomfield took Westinghouse to court over the pollution and won. This begs the question of why did Westinghouse allow the dumping during the war and after, and why such pollution did not reach the spotlight until the 2006 court date. But the most important question to ask is whether surrounding houses were affected by this pollution, and if so how many innocent people became sick because of it.

Final Report:

On a quiet night in 1942, a sewer fire breaks out near the Westinghouse Electric Plant in Bloomfield New Jersey, personnel from the plant rush out with fire extinguishers trying to put out the blaze that fan out from the gutters. Fire crews arrive on the scene and help with the blaze but were left in the dark when questioning about the source of the fire. Personnel try and make up an excuse almost like they were hiding something from anyone not affiliated with the factory, and they were.[1]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Bloomfield plant manufactured lightbulbs and Mazda tubes, a special type of vacuum tube, for the consumer market. They also tried to experiment with using uranium metal wire as a replacement for the existing tungsten wire for the filaments in light bulbs. This project was deemed a failure but gave Westinghouse valuable knowledge in the manufacture and experimentation with small quantities of uranium.[2] While Westinghouse dabbled in using uranium for light bulbs, other institutions in the United Sates began to look into uranium and similar metals for the production of nuclear research; one site of particular importance was the University of Chicago, who was trying to create a self-sustaining reaction and was in need of about 3 tons of refined uranium metal. The head of the Metallurgical Department at the University of Chicago, a Mr. Arthur Compton was the individual who placed the order for Westinghouse to deliver. The large quantity at first seemed impossible for Westinghouse to create but eventually set up a permanent manufacturing system in the basement and roof of the No. 7 Building of the plant. The creation of uranium metal was a complex and dangerous endeavor, with the uranium having a nasty habit of spontaneous combustion that would cause fires to break out all over Building No. 7 as well as the sewers where by-products of the process were dumped into.[3] The cause of dumping this waste and the constant threat of fires at the plant were because of one reason, the United States was at war and the University of Chicago was laying the groundwork for the Manhattan Project using Westinghouse uranium. Richard Farnham, was a Bloomfield native who was hired by Westinghouse in 1942 as a quality controls engineer, he recounts his experiences during the war and the conditions at the plant. “Secrecy was absolute, or at least that was the intention. There seemed to be a deliberate effort to hire workers who knew nothing about chemistry.” John Gibson, another worker at the plant during the war, described how he and other workers felt about the uranium they were producing, “At Westinghouse, my own recollection is that the metal powder was regarded as sinister stuff. After all, it had the tendency to burst into flames at room temperature. But attitudes towards it were casual. No special precautions were taken, for example, in carrying the buttons around by hand.”[4]

The United States wanted to keep such a tight grip on the security of the project that it is as if they did not care about the adverse health effects on the workers at the plant as well as the effects of these poisonous chemicals being dumped into the city’s sewer systems. This paper will try and unravel the rationale behind government oversight being so skewed towards secrecy instead of a more balanced approach to the project, what health risks have workers suffered during and after their employment at Westinghouse and what kind of environmental damaged was caused in the immediate area of the plant. Furthermore, if damage did occur to a serious degree was any clean up performed by Westinghouse to turn the area safe. This paper will also dive into the legal aspects and look for any litigation filed against Westinghouse by the people of Bloomfield in regards to the damage caused by the uranium manufacture.

Westinghouse Comes to Bloomfield

Before this paper will discuss the lack of oversight from the US government, some context must be put in place first. What was known as the Westinghouse Lamp Plant was first erected in the early 1900s and produced conventional lightbulb filaments made of tungsten. These lightbulbs were known by the name Mazda Tubes, and were the primary bread and butter for the plant up until the 1930s, right before construction took place to expand the facility and its manufacturing capabilities.[5] The postcard shown below was how the factory originally looked prior to the expansion before the Second World War:

Westinghouse Plant Postcard with Arlington Ave. in foreground (circa 1920s)

With the dawn of the 1930s and the beginnings of nuclear science, the Westinghouse Plant adapted to begin a small production line to create small amounts of uranium metal (each sample weighing about an ounce or so) and sold these slugs to universities and research laboratories to study if radioactive metals held promise for the future.

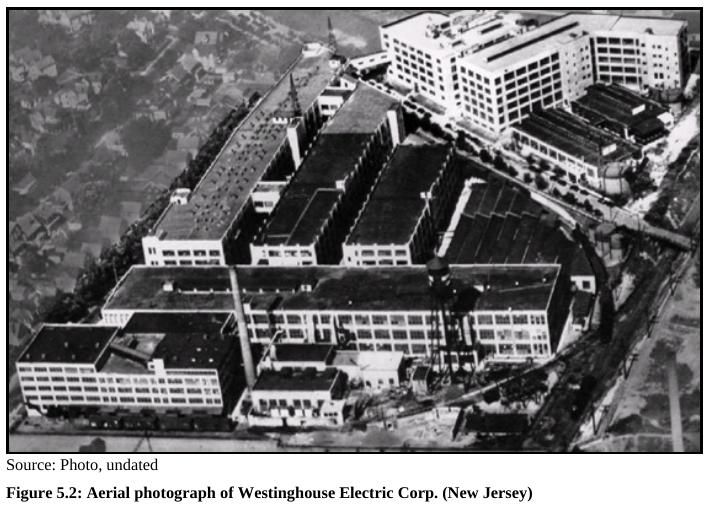

With the plant expanded to its full capacity, new buildings were erected to provide new assembly lines for the manufacture of consumer goods and freeing up space for a uranium production line to set up in the roof of building No. 7 (Building directly above from the water tower). After the outbreak of World War 2, Westinghouse was contracted under secrecy by the United States Government to start production of uranium metal since no other factory in the United States had any kind of manufacturing established. This sent engineers at Westinghouse scrambling to go from producing an ounce or two for a local university to making 22 pounds in three months’ time. Employees began by either buying or stealing all metal garbage cans in the area to use as makeshift tubs for the holding of chemical soups that would turn uranium salts into brittle cakes that could be melted down and cast into ingots. In total, the site made just short of 69 tons of these ingots that proved invaluable to the government but also spilled out an unknown quantity of waste and by-products directly into local sewer systems.[6] This in itself is a heinous act but what makes this even worse is that in the aerial photograph of the plant, it is surrounded on all sides by residential housing whose inhabitants could have easily been poisoned by these toxins if they managed to seep out of the sewer drains and saturate the underground water table and surrounding soil. From the information that has been published about this site, it appears that no adverse health effects have stricken the immediate population around the present day site, however contamination of soil samples have been confirmed to be at elevated levels and needed to be removed after the plant shut down. While civilian illness in regards to the toxic pollution that Westinghouse created and illegally disposed of appear to have no cases, the same cannot be said for those who worked at the plant.

Uranium Production and Pollution

John Gibson, an engineer who worked at Westinghouse during the war discussed how the factory workers who were creating the uranium ingots ranged in reactions to their dangerous lines of work. Some did not give it a second thought to others becoming petrified and refusing to work until management brought in a team of experts to calm down the situation and assure people they were going to be all right around these radioactive elements. “Workers were given x-ray film to carry in their pockets and monthly urinalysis checks were conducted in addition to monthly x-ray scans. One practical joker dropped a few grains of uranium into another man’s urine sample, and then man was rushed to the hospital before the matter could be cleared up”. From the words of Mr. Gibson, it appears that the plant took employee health very seriously as can be concluded from that prank, but that was when obvious levels of radiation were detected. More exposure that is passive may not have shown up in these monthly scans and urine tests, possibly putting these workers at risk for diseases and cancers later in their lives. A female worker who checked the outgoing metal for purity using a spectrographic test died shortly after the war, with some employees, speculating her death was because of the uranium, but nothing was confirmed leading to speculations and fear[7]. If we are to assume the worst and say that this poor woman passed away due to her line of work, what does that say in regards to the safety measures that were put in place to keep employees from getting sick? Workers who handled the finished ingots were quoted as being indifferent to the handling of radioactive materials with bare hands and no radiation protective clothing. Secrecy and expedient delivery of top-secret war materials should not trump the basic health and welfare of the workers under government contract employ. Westinghouse could have easily requested protective equipment for the workers to prevent exposure and a speculated fatality.

Westinghouse’s participation in the Manhattan project culminated with the dropping of two atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the Second World War. The workers who dedicated 18 months of service to the Tuballoy project left Bloomfield almost immediately and went on to find other jobs across the nation, but the wounds etched into the earth beneath the site would soon morph into scars, scars that would take decades to remove from the earth. Immediately after the war, Westinghouse promptly began to remove all machinery, pipes, and other materials that were in contact with the uranium process and carted them away to a location that was unknown at the time and is still unknown to this day. While everything appeared to be gone from the surface, underground piping remained buried and continued to leech isotopes into the soil through the porous and corroded pipe walls. Due to the possibility of leeching these contaminants into the water table that sat under the plant, a survey of Manhattan Project Sites determined that the basement of Building No.7 needed to be excavated and disposed of. In total about 55 barrels of contaminated soil were removed for the second round of clean up at the Westinghouse plant[8].

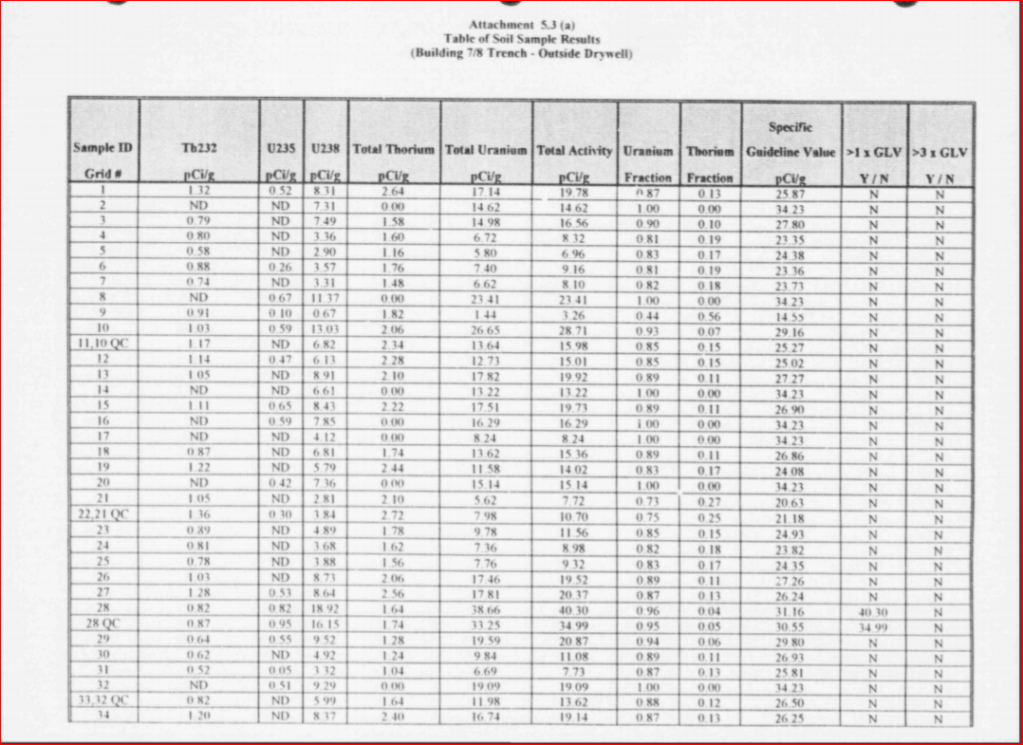

Once the cleanup was completed Building No. 7 was determined to now be safe, but another problem was soon discovered that could not be remediated at this time. A section of underground pipes ran from the basement of Building No. 7 to the basement of Building No. 8, where another portion of the Tuballoy process was undertaken. These pipes and drywell showed low-level isotopes within the metal and surrounding soil, which needed to be removed so another survey was conducted. In July of 1996, a Nuclear Regulatory Commission, undertaken by the Scientific Ecology Group examined this stretch of land between Buildings 7 and 8. The survey reports state, “Several areas were identified where residual radioactivity in the soil exceeded the guideline for unrestricted use. Several other areas were also identified in which buried piping containing radioactive materials may have affected the surrounding soil media”[9]. The first steps in the now third cleanup attempt were to grid off the affected area into sections about a meter square. These squares were tested for surface levels of contamination before being dug up to within 6 inches of the subterranean pipes before the excavated dirt was disposed of. Once the pipework was taken care of, work then turned attention towards the foundation walls of building No.7 where most of the uranium production took place. Samples and analysis of the foundation found levels of radioactive contaminants that thankfully were able to be decontaminated by hand. Should levels still be seen as exceeding safe limits the affected area was then re scrubbed and tested again.[10] On the next page will be one table of recorded contaminants that were found in the pipe trench between the two buildings in question:

[11]

[12]

These two tables are just a sample of the amount of data that was recorded for each specific sub-section of the land between buildings 7 and 8, precise recording of individual possible elements that could have or were found in the soil were meticulously recorded and then those levels were compared to the expected surrounding concentrations. From the tables upon tables and all the field calculations done by SEG agents, it was determined that approximately 2,866 cubic feet of top soil, pipes, concrete and other materials from the trench were removed and disposed of. The now open trench was then given the green light to be back-filled with clean soil and the area was deemed safe for unrestricted use[13]. After the 1996 survey the lot that once was home to Westinghouse was barren and empty, all buildings were torn down and all equipment was removed. The employee parking lots just down the street from the facility on Arlington Avenue became the home for a junkyard and the site was left empty, plans were tried to build upon the land and redevelop it, but those were unsuccessful up until 2018, when a future free of toxins was a possibility for the site.

“Westinghouse Electric Corp. factory site’s 13.5 acres eyed by Bloomfield for development”[14] was the title for an article published in the North Jersey newspaper that hinted at the possibility of the old empty lot finally getting a new lease on life, but first needed to prove itself to the township before it got the all clear to start on construction. These development plans were approved by the township in early February of 2018, but the road to approval had one major obstacle in its path before ground could be broken.

12 years prior to Bloomfield’s approval to build new housing on the Westinghouse site, Phillips Electric N.A. the owners at the time of Westinghouse Electric were brought to court by the people of Bloomfield and Essex County. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and the citizens of Bloomfield acting as plaintiffs filed a civil complaint against defendants Westinghouse and Phillips Electric N.A. on the grounds of continuing to contaminate soil and water underneath the lot. Titled “Prayer for Relief”, the demands of the plaintiffs were for the defendants to fund NJDEP to clean up all remaining sources of contamination that would be able to seep through the soil and into the underground water reservoir that flowed underneath the site and discharged into nearby streams and rivers.[15]

“38) The soil and groundwater investigations at the Bloomfield site were conducted by Westinghouse in three phases, the results of which revealed the presence of various hazardous substances exceeding plaintiff DEP’s cleanup criteria in the soils and groundwater, which substances including Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), arsenic and radiological, including uranium”[16]

“39) As a result of its investigations, Westinghouse identified the primary sources of groundwater contamination at the Bloomfield site as leaking underground storage tanks (USTs), contaminated soil and underground water reservoirs”[17]

“46) Although defendant Viacom and its predecessors have initiated the remediation of the Bloomfield site, the groundwater and soils contamination continues”[18]

The above mention paragraphs taken from the court transcript paint the picture that up until the court case, those underground tanks, contaminated soil and reservoirs were never taken care of in the previous three cleanups that came through Westinghouse. With these hazards still interred beneath the soil and the groundwater a major source of potable water for the residents of not only Bloomfield but also of surrounding communities, there was a huge potential for locals who drank the water to become sick from any number of chemicals that were in their drinking water. The plaintiffs also argued in their case that the existence of contaminants in and under the Westinghouse site were a form of trespass against the people, who could not and would not consent to the existence of toxins that were invading their homes through contaminated water. The residents also demanded that Westinghouse pay them compensations until the problem was remedied, and from the court documents, it appears that these fees were paid as the final remnants of pollution were removed from the site for good.[19]

With the site finally made clean and available to be built upon, we return to the year of 2018 when Bloomfield approved the construction of housing upon the Westinghouse site. Before construction began on the site, virgin soil needed to be carted in to fill any holes that were left open and to level the surface on where construction was to take place. Matt Kadosh, writer for North Jersey and author of the newspaper article visited the site before construction began and noted on the progress at the time. “50,000 cubic yards of soil replaced in Bloomfield? That’s right, here at the former Westinghouse site.”[20] Construction at the site continued up to the present day with multiple building skeletons being erected over the two years and it seems that all the troubles of the site have for now, left for good.

Conclusion

It has been a long 86 years since that fire erupted back in 1942 at the Westinghouse sewers. Uranium was melted down into ingots that helped the US win the war with the atomic bombs as well as cause an environmental disaster, and it was all because of the United States government’s skewed viewpoints on national security. They intentionally hired people with no experience in the field of nuclear science to preserve secrecy, but because these people had no clue on what they were making or the ramifications of if they did, something wrong, waste spills and pollution would be rampant. Employee health was not much better, relegated to x-ray film and monthly urine tests that may or may not have been able to detect slow accumulation of radioactivity in the employee’s bodies. All of these issues and fallout (No pun intended) could have and should have been remedied and still secrecy could have been kept to keep prying eyes away on the home front. Instead of hiring inexperienced people with no knowledge on the type and scale of work they would be contracted to, the United States could have turned to its multiple of universities that had fresh and eager minds that would have happily worked in a lab instead of being sent over to the front. Radioactive protection could have also been provided to these workers to keep them a lot safer than the indifference the workers at the site had when handling the uranium slugs and ingots.[21] Of all the blunders that occurred at the Westinghouse site, the main concern should be that in the case of creating a top secret project, whether that be for war or peace, should never under any circumstances come into conflict with the health and safety of the workers and the environment to a secondary extent. When governments or other agencies of significant power don blinders that keep them from seeing anything else other than secrecy and “National Security” the effects can turn deadly for humans and nature, and that is something that should never be forgotten.

[1] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

[2] John A. Gibson “Bloomfield’s Part in the Atomic Bomb: The Tuballoy Project” The New Town Crier 2 no. 11 (2004): 1-2.

[3] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

[4] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

[5] John A. Gibson “Bloomfield’s Part in the Atomic Bomb: The Tuballoy Project” The New Town Crier 2 no. 11 (2004): 1-2.

[6] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

[7] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

[8] John A. Gibson “Bloomfield’s Part in the Atomic Bomb: The Tuballoy Project” The New Town Crier 2 no. 11 (2004): 1-2.

[9] D.M. Hall, Donald R. Neeley, “Westinghouse Bloomfield Lamp Plant Final Survey, Excavated Trench Building 7/8 Trench Closure Plan” (Scientific Ecology Group INC. 1996) 1-1187.

[10] D.M. Hall, Donald R. Neeley, “Westinghouse Bloomfield Lamp Plant Final Survey, Excavated Trench Building 7/8 Trench Closure Plan” (Scientific Ecology Group INC. 1996) 1-1187.

[11] D.M. Hall, Donald R. Neeley, “Westinghouse Bloomfield Lamp Plant Final Survey, Excavated Trench Building 7/8 Trench Closure Plan” (Scientific Ecology Group INC. 1996) 1-1187.

[12] D.M. Hall, Donald R. Neeley, “Westinghouse Bloomfield Lamp Plant Final Survey, Excavated Trench Building 7/8 Trench Closure Plan” (Scientific Ecology Group INC. 1996) 1-1187.

[13] D.M. Hall, Donald R. Neeley, “Westinghouse Bloomfield Lamp Plant Final Survey, Excavated Trench Building 7/8 Trench Closure Plan” (Scientific Ecology Group INC. 1996) 1-1187.

[14] Matt Kadosh, “Westinghouse Electric Corp. factory site’s 13.5 acres eyed by Bloomfield for development” (northjersey.com February 6, 2018) https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/essex/bloomfield/2018/02/06/westinghouse-electric-eyed-bloomfield-development/307973002/

[15] NJ D.E.P and N.J.S.C.F v. Viacom Inc.; Phillips N.A., (D.C. New Jersey. 2006)

[16] NJ D.E.P and N.J.S.C.F v. Viacom Inc.; Phillips N.A., (D.C. New Jersey. 2006)

[17] NJ D.E.P and N.J.S.C.F v. Viacom Inc.; Phillips N.A., (D.C. New Jersey. 2006)

[18] NJ D.E.P and N.J.S.C.F v. Viacom Inc.; Phillips N.A., (D.C. New Jersey. 2006)

[19] NJ D.E.P and N.J.S.C.F v. Viacom Inc.; Phillips N.A., (D.C. New Jersey. 2006)

[20] Matt Kadosh, “Westinghouse Electric Corp. factory site’s 13.5 acres eyed by Bloomfield for development” (northjersey.com February 6, 2018)

[21] John Walsh, “Manhattan Project Post-Script” Science 212 no. 4501 (1981): 1369-1371.

Primary Sources:

Source 1: New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection v. Phillips Electronics North America Corp. (Essex County Court, 2006)

Shortly after the closure of the Westinghouse Electrical Plant (by this time now a subsidiary of Philips North America) cleanup actions were underway to demolish and remove all hazardous materials from the sight after production of not only the Manhattan Project uranium but also thorium light filaments. The cleanup did not get rid of all materials and the city filed a civil suit against Philips over the alleged shortcuts they took while disposing of contaminated soil and other materials. Citing possible water table contamination from underground storage tanks that at the time of this suit, were still buried under the site. This court case followed in the footsteps of many other landmark battle for environmental justice within the state of New Jersey and continued the pursuit of having massive corporate entities be held accountable for their mismanagement of delicate cleanup operations.

Source 2: A Manhattan Project Postscript (Science Magazine, 1981) by John Walsh

Taken from the first hand account of the author during his tenure at the plant between 1943 and 1944, Manhattan Project Postscript reveals what went on behind the scenes at the Westinghouse Factory during the Second World War and how their production of enriched uranium ingots played a hand in the final development of the Atomic Bomb. Walsh not only discusses the work that he saw on the manufacturing of ingots, but also in the early days of small scale manufacture just how hazardous these production methods were and how the workers that were hired to create these ingots also were flushing radioactive waste down into the city’s sewer systems, potentially being the catalyst for future battles yet to come.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/212/4501/1369

Source 3: July 1996 Contamination Survey Report by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Over the summer of 1996 when the demolition and cleanup of what used to be the Westinghouse facility was already underway, the Scientific Ecology Group; with oversight from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, performed a soil sample test of a subterranean pipe and drywell running from Building 7 to Building 8. Building 7 is where the production line for the uranium existed and would logically be the source of the highest contamination levels and that was proven to be true, with levels exceeding the guidelines for that soil to be used in unrestricted uses. Due to the elevated levels of uranium and thorium approximately 2,700 cubic feet of soil, pipework and foundation from Building 7 had to be partially decontaminated and hauled away to a radioactive dumping site.

Source 4: The Tuballoy Project (The New Town Crier) May 2004

Taking a much more general view of the Westinghouse site, It describes how Westinghouse first dabbled in using uranium for commercial purposes before the war, their upmost priority of secrecy during their contract for the Manhattan Project and the unfortunate pollution caused by the manufacturing process. Their work was so secretive that whenever something went wrong it was up to the discretion of personnel (who had no knowledge of what they were making or of nuclear science) to put out fires and dump refuse into the sewage system, which would also sometimes catch on fire. Due to this lack of oversight contamination was present at Building 7 and after the war, most of the machines and pipework that made the uranium was stripped away and taken to an undisclosed location, which begs the question of is this location disposing of waste properly, however that should be answered with another essay.

Secondary Sources:

Source 1: Westinghouse Property eyed for Development (NorthJersey, Feb. 2018)

Despite all the pollution and damages that the Westinghouse site has caused to the town of Bloomfield, the damage was able to be contained, disposed of, and the land become useable again. Because of this the town has decided to capitalize on this “free” land and build upon it a better economic solution for the town. Gone are the days of radioactive waste dumping, chemical fires, and no government oversight for pollution. Now the new site will be home to businesses and housing that will allow Bloomfield to economically rise up without the toxic baggage of the past that helped the town prosper.

Image Analysis:

This postcard from 1920 shows the beginnings of the Westinghouse Electric Lamp Plant in Bloomfield NJ, shown from the perspective of what is now Arlington Avenue looking west towards where Watsessing Station would be today. At the time this photograph was taken this site was relatively uneventful, creating electric lightbulbs and other consumable products for the growing masses to purchase but all that would drastically change in the coming decades as the township of Bloomfield grew out from the trees and grassy hills that surround the plant.

With the plant, being such a crucial part of the local economy there was an influx of eager workers and engineers who wished to be under the employ of the company. With the increase in workers came the increase of housing built around the plant as well as new facilities to expand production as well as a research laboratory to look into new technologies that could improve the manufacturing of lightbulbs and other goods. At its peak, the plant covered the entirety of the original build lot and had to purchase more land east of Arlington Avenue to accommodate the new structures.

By the early 1940’s the Westinghouse plant became a sprawling center of manufacturing that quickly became surrounded by residential housing as seen in the photograph above. Production of electrical components got kicked into overdrive with the United States’ introduction into the Second World War, with the facility producing explosives and electronics for the war effort. But deep within Westinghouse’s building 7 (the North-South facing building directly above the water tower) was the production line for creating nuclear materials for the Atomic Bomb project, and whose run-off was dumped into the city’s sewer system.

These two pictures show not only the expansion of Westinghouse, but also the expansion of Bloomfield, with each year a new building was erected on the site and that in turn brought in more people to live, work and bolster the economy of the town.

That being said the scary part is how close people were living in relation to the plant, and with poisons being leeched into the soil and groundwater immediately below the plant, everyone was in great danger of contracting some type of illness from the run-off. The second picture with the factory in focus and the surrounding housing blurred and greyed out is almost akin to a crosshair, focusing on the source of unknown pollution (at the time).