Taking our Power Back: The 2023 Build Public Renewables Act in New York & Making Climate a Popular Movement

by Anjali Madgula

Site Description:

In 2023, New York state passed the Build Public Renewables Act (BPRA). This landmark bill authorizes the New York Power Authority to build publicly owned renewable energy projects with a good green jobs program for workers to transition from the oil and gas sector. Public power is not a new concept, it has a rich history from the FDR era to now and it targets the profit incentive of private utility companies. The BPRA effort was won through over 4 years of grassroots organizing in New York. The coalition that won BPRA was led by NY’s chapter of Democratic Socialists of America. My project follows the chronology of their campaign. I research their fight to think about how environmental campaigns can put economic issues first to make climate a popular movement for all.

Introduction

It’s the last week of March 2023 and you’re gliding past Rensselaer toward Albany on Interstate 787. On your right you start to catch sight of a smooth green billboard peeking out over a troupe of gray trees still barren from the winter. The abundant greenness of the sign draws your eye as you get closer. You glimpse at the balanced poise of a giant hand rising from the sign’s bottom right corner, and discover the wind turbines and solar panels neatly cradled in its palm. The statement stretching out on the rest of the billboard reads, “More New Yorkers want to Build Public Renewables than voted for Kathy Hochul.” 1 If you are driving to Albany, chances are you know exactly who Hochul is. You wonder, why is the governor of New York being called out?

You make a mental note of the phrase, “Build Public Renewables”, underlined and in bright yellow text, illuminating under a glowing yellow dot of sun, clearly the point of contention between Hochul and whoever made this billboard. Unless you keep up with energy politics, you probably haven’t heard of that phrase before. Building renewable energy sounds familiar enough, a call that has been loud and clear from environmental activists. But public? This might be more than your average environmental campaign. The billboard suggests that the idea of public renewables is highly popular with New Yorkers, more popular than Hochul. You aren’t sure how Hochul feels about public renewables but it seems like if she doesn’t support it, there could be some tension here. There’s something teasing about the wording. Are they implying that Hochul’s seat in power could be threatened, that she could be voted out by these supporters of public renewables?

A month later, the billboard’s confrontational message had clearly worked, Hochul passed the Build Public Renewables Act (BPRA) with a majority of its original language in New York State’s annual budget. The BPRA is a huge milestone in environmental policy across the country and an incredible victory for the NYC chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), the key organization behind the bill. The billboard was one of DSA’s final strategies in a four year long campaign that ran ads, town halls, rallies and more. The BPRA establishes a plan for NY to build renewable energy but importantly, through public rather than privately owned projects. 2

In the immediate aftermath of the victory, progressive, environmental, and socialist3 magazines wrote headliner articles4 that cover the many aspects of the BPRA bill, importantly its green union jobs program and discounted utility rates, while giving kudos to the ecosocialist vision at the center of the campaign. These articles5 focus more on the later stages of the BPRA campaign and the strategies to pressure people in power that eventually led to its success.6 I am interested in focusing on the earlier stages of the campaign. The articles celebrate that the BPRA campaign brought economic issues and environmental issues together but many climate organizations like Sunrise Movement and Climate Justice Alliance have made connections between economic concerns and environmental ones. I am interested in further charting what makes the BPRA campaign stand out from other climate campaigns.

I argue that the BPRA campaign succeeded because DSA organizers not only brought economic and environmental issues together but they fought for economic issues first, and then environmental issues. This chronology was important for grounding the campaign in the struggles that affect marginalized neighborhoods and working class New Yorkers in their day to day lives. If the campaign had tried to fully tie economic and environmental issues from the start, it would not have been as well-received. My project considers the following questions: As people deal with a rising cost of living on multiple fronts, is it necessary for climate campaigns that aim to build mass movements, to only crystallize after existing as economic relief campaigns? Is it better for organizations that can adapt, can make detours, and have the chops to organize around various issues to take on climate organizing? What is the role of political education and messaging in turning an economic campaign into a bold eco-socialist campaign?

I begin my study by first providing a brief background on public power history in the United States and ecosocialism as defined by the DSA. Then I examine how BPRA organizers first sprung into action around the economic issues in their neighborhoods. I explore how BPRA organizers pivoted their campaign to a vision for publicly owned renewable energy that targets private profit motives as the reason for both economic and environmental inequities. How did the organizers make that turn? To answer that question I will analyze the political education, town halls, and messaging that steadily propelled the environmental turn of the campaign while not losing the fundamental economic message. I will conclude by considering how future climate campaigns can use the BPRA campaign as a model for making climate a popular mass movement.

I approach this paper by synthesizing public writings, social media communications, and videos created both during the course of the BPRA campaign and after its success. I also draw from a broader study of DSA as an organization from the public platform of the organization, and reaffirmed by my own experiences. I thread DSA’s current call for public power with a larger history of public power campaigns in the US. To situate DSA’s approach to environmental organizing in comparison to other climate focused orgs, I reaffirm my research with my experience in the US climate movement since 2019.

Ecosocialism Then & Now

A local election poster in 1937 in Reading, Pennsylvania, promoting the creation of a municipal power plant.9

Publicly owned power is not a new idea, in fact, the first public municipal owned power utility began in 1880 in Wabash, Indiana. Wabash’s City Council decided to own its electric system instead of franchising a private company to administer it. Publicly owned power was very common until private companies more aggressively began to stake their claim for ownership as privatization became a more common thread across industries7. Infamously, JP Morgan merged all of the gas companies in New York to create “Consolidated Gas”, a for-profit gas company that charged New Yorkers huge markups on their utilities. 8Then, Franklin D. Roosevelt, using his mantle as president, described “the right of people to own and operate their own utility”9 as a protection against the greed of private utility companies. Even then, the private business lobby claimed Roosevelt’s vision was too socialist. Regardless, FDR was successful in turning the tide towards public power once more, creating the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) at a time where he felt economic relief and job opportunities were much needed. Government investment in the TVA allowed for a bold creative program for building the largest hydropower utility with a goal of flood control and reforestation. Removing the profit incentive, allowed for new priorities and needs to be valued. Unfortunately private utilities as both generators and distributors of energy are almost hegemonic today. However, the TVA still exists as a pillar of public power, providing energy for millions of people while practicing environmental stewardship of public lands.10

Today, the DSA, with over 100,000 members nationally and chapters in every state, organizes for immigrant justice, anti-war movements, union power, Medicare4All, and a Green New Deal. DSA grounds its fight for ecosocialism in its broader vision that working people should “run both the economy and society democratically to meet human needs, not to make profits for a few”. The issues of the JP Morgan era have not changed. Consolidated Gas is now Con Edison, the private utility company of New York, that has lobbied against renewable energy options because staying with fossil fuels is more profitable for them.10 Today public power is not a central tenet of the broader environmental movement, but certain DSA chapters and local groups have been resurfacing this demand as an important ecosocialist intervention in the call for renewable energy. Today’s fight for public power is grounded in a powerful history that has always prioritized economic relief first as a pathway to environmental programs.

The Economics

“Without the light, you don’t have access to anything really,” says Ashley, a Black mom and resident of East Flatbush. She is sitting out on her porch in a tank top and you can feel the heat of the summer night buzzing through the screen as you watch her interview. Ashley is talking about a blackout that has gone on for more than 8 hours in her neighborhood for the 2nd time in 3 weeks.11 It’s the summer of 2020, and both East Flatbush and East Bronx have borne the brunt of energy grid failures worsened by summer storms and heat waves. In times of grid overload, Con Edison has to choose certain neighborhoods to blackout in order to prevent massive outages. Rich neighborhoods and tourist hotbeds like Times Square with its glimmering billboards were kept running, while East Flatbush, East Bronx, and Canarsie were cut off.12

DSA members did video interviews with over 10 residents of these neighborhoods, talking to people about the blackouts. The interviewers asked how the blackouts affected their day, if any of their food and medication went bad, and how they felt about ConEdison. Almost everyone had their food, fresh produce, and meats spoiled due to their refrigerators being shut off. Others spoke about being unable to plug in health equipment for elderly family members, which was vital especially during the height of the COVID pandemic.13 One woman expressed needing to get a hotel for a family every time there was a blackout. Almost all expressed disappointment with Con Edison’s lack of reliability.14

At this point in time, NYC DSA members had formed an ecosocialist working group that was already starting to ideate around a campaign for public power, voting to make it a priority in 2019.15 While the DSA did set this goal to organize for public renewable power, they took long detours to get there, to focus on analyzing the economic issues affecting people in regards to utility companies. I argue that these early detours in the campaign were a vital part of building a stronger, more popular movement.

In March of 2020, NYC DSA ecosocialists along with their broader chapter, organized successfully to demand a moratorium on utility shut offs, in coalition with other organizations.16 By 2018, nearly a 3rd of US households had reported having trouble paying their energy bills, with ½ of those people identifying as Black, and 30% identifying as Latino. 1 in 5 households reported going without food, medicine, and other needs to pay their utility bills. Many people were not using heat or air conditioning, even in unsafe temperatures, in order to save money.17 This economic insecurity was only exacerbated during the COVID pandemic, causing economic inequalities to deepen.

DSA organizers started to demand that Con Edison use their record breaking profit in 2020 towards canceling utility debt.18 They worked with housing organizers to advocate for rent strikes and utility strikes as part of a pressure campaign to demand Governor Cuomo and Con Edison to provide relief for working people. DSA ecosocialists continued to agitate around a clear message: New York’s private utility company was putting marginalized communities at risk of blackouts while raising their utility bills, and not even changing course during a national crisis. Private utility companies were not going to change, their priority would always be profit.

As the summer of 2020 brought an important movement for racial justice, DSA organizers shifted their priorities to participating in mass protest, while continuing to canvas, hold town halls, and hear concerns about utility rates and blackouts. During this time, the Wall Street Journal had published an article citing that public utility companies across the country were more reliable than private ones.19 Public disapproval of Con Edison’s rate hikes and power grid blackouts was becoming a clear and popular narrative, even taken up by more mainstream news networks.

DSA was starting to put out content about “Public Power”20 rather than public renewables or any other variation. Public power as a term focused people towards the concrete political theory behind the campaign: that private ownership of utilities was not working for people’s needs but rather against them.

In August of 2020, DSA ecosocialists paired up with housing organizers to march to “Cancel Rent and demand Public Power”.21 Hundreds of people took over Livingston Street in Brooklyn to march to Con Edison’s office, wearing masks to protect each other from spreading COVID , protest leaders led chants oscillating between “Hey Hey, Ho Ho, Con Ed has got to go!” and “What do we want? CANCEL RENT! When do we want it? NOW!”22. Public Power was clearly a movement for people fed up with the stresses of utility and rent burden to organize around their frustration. It was also clear that the bill DSA organizers were forumalating would center language around discounted utility rates for all. All of this work was important for both creating a mass consensus around the need for public ownership of our utilities over private, and for DSA organizers to ground their vision in the everyday concerns people had.

Environmental Turn & Political Education

Now that DSA’s ecosocialists were starting to build community and even hold rallies, they needed to make it clear that capitalism was the reason for Con Edison’s commitment to both high utility rates and fossil fuels. Further, they needed to unite people to support their now drafted, BPRA bill.

While canvassing and holding town halls, DSA organizers had been working with the AFL-CIO, a national labor union, and environmental coalitions, to form a statewide group called Public Power New York (PPNY). This coalition co-created what became the Build Public Renewables Act, a multi layered bill that outlines exactly the process with which public power would be possible. Organizers had decided to orient their bill around the New York Power Authority (NYPA), an existing public power utility created by FDR that had been barred from actually taking on projects, to empower it to be in charge of renewable energy projects.23 The bill called for the shutdown of 6 harmful peaker plants in margninalized neighborhoods, gold standard labor law for energy workers to transition into unionized renewable energy jobs, discounted utility rates for all, and for our energy to be publicly and democratically generated. While ideas had been thrown around to call for a second bill that would make Con Edison, a utility distributor also publicly owned, coalitional organizers decided to first cohere around the BPRA and intervene in the generation of energy first. 24

But if this was going to be a statewide campaign, they would need to organize across the state to popularize their platform and educate people on how the current energy system was failing. I argue that political education was an important aspect of the campaign’s ability to connect Con Edison’s lack of reliability, its rate hikes, and blackouts, with the fight for renewable energy now. BPRA campaign’s political education, messaging, and communications was able to incorporate environmental justice ideas and history while maintaining the underlying economic issues at play.

Prioritizing education also helps clarify the precedence for this campaign. Many of us do not know our country’s public power history. Learning about it makes the idea of changing our energy utility public seems more possible. There are over 2,000 towns in the United States that still do have public municipal utilities, with statistically cheaper rates than private utilities.24

Some parts of the state were more than clear on the intersecting harms of private utility companies. The people of Astoria and the Bronx have long termed their neighborhoods, “Asthma Alley” in reference to the harmful air pollution from Con Edison’s peaker plants that run right near their homes. Sebastian Baez grew up right off the Triborough Bridge, a mile and half from a peaker plant. Sebastian shares his story via a video interview with DSA, recounting his childhood soccer games in the shadow of all of that pollution, causing him and his peers to develop asthma.25 No one in these neighborhoods is a stranger to the harm fossil fuels perpetuate in their daily lives, and the reality that they are footing the bill as utility customers.26 The BPRA bill mandates the closure of 6 Con Edison peaker plants by 2030.27 But untangling the deeper reality of these contradictions requires an understanding of how energy works, why Con Edison is disincentivized from changing their energy grid, and New York climate law history.

The campaign produced a regular ”Public Power Hour” and “Energy 101 Orientation” featuring guest speakers to easily communicate the various moving parts of New York’s energy history. One important piece of information was that New York had passed a climate bill in 2019 mandating the state to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030, and 85% by 2050.28 DSA organizers pointed out that under the current system, private companies would be tasked with this roll out of solar and wind energy, yet they were failing to meet these timelines. The reason for the stall? Profit. “If the transition to green energy has to wait for an entire industry to determine whether it can make a profit on every single solar panel or wind turbine, we could be waiting far too long.” Under private industry’s profit motive, endless resources like wind and solar would be treated like scarce commodities.29 Therefore, public power is not just an ecosocialist spin but the only way that New York could actually meet the climate goals it already committed to.

Organizers also brought their political messaging to the streets. In the summer of 2021, DSA activists protested politicians who were refusing to support the BPRA by holding up signs that depict their faces on Venmo graphics, showing all of the fossil fuel money they receive. Using public records to follow the fossil fuel industry’s money trail to both Con Edison and status quo politicians, made it undeniable that capitalism was keeping New York from a real renewable energy rollout.30

Ultimately, this political education geared the campaign’s ability to elect Sarahana Shresta, a DSA member in Mid-Hudson Valley in upstate New York, whose platform was almost entirely about public power and the BPRA bill. Shrestha made clear her support as opposed to her opponent, Kevin Cahill’s lack of support for public power. As we’ve seen in most national and state level elections, economic issues or “bread and butter issues” are understood as the most important priorities for prospective voters. DSA canvassers clear framing of the need for public power resonated with people. In an interview, Shrestha says, “People are realizing that they will never be able to hold a corporate monopoly accountable…When I say that the energy system should exist to serve people, that energy should be like water, people instantly get it…they instantly get that this is something we need for our survival, for our quality of life.” 31 The implications of Shrestha’s win are profound- public power was not only popular but winnable. Democrats and Republicans alike took note of this popularity, it made them realize that they might need to get on board with the BPRA if they wanted reelection.

I argue that it is rare for an environmental policy bill like the BPRA to have garned such popular support, especially at a statewide level. BPRA organizers were able to bring the energy and frustration at the heart of their early economic relief campaigns toward a major ecosocialist win using a sharp unified message. This message is best articulated by Zohran Mamdani, a DSA socialist elected to New York state assemby: “We need an energy system that treats energy as it is: a public good, and prioritizes people and the planet over the profit of wall street investors.”31

Conclusion

My project is meant to be in conversation with environmental activists, like myself, who have long been wanting climate action that matches the urgency of the climate crisis. As natural disasters become more commonplace and summer heat waves become more deadly, it can only feel despairing to know we have no government plan to call this crisis a crisis. However, using the BPRA campaign as a model, I advocate that starting with campaigns for economic relief might actually fast-track our climate campaigns. For massive change, we need to make climate a popular movement for all, that inspires the possibility of near victories rather than far, and the possibility that a green economy won’t just continue to codify the economic inequities in our current economy.

Energy affects all of life-it keeps the lights on at work, keeps our trains running on our commute, keeps the lights on at home, powers our internet to create global economies, keeps our food fresh, provides both heat and air conditioning when the temperatures outside are extreme. Our economic concerns are one in the same with our environmental concerns and we can win big on climate when we address the root issue: profit over people and the planet.

The BPRA campaign is a good model for experimenting with a new climate movement that builds from the past-one that threatens to take away the private designation of corporate powers that run so many of our services if they don’t both meet economic and environmental demands. In the same vein, BPRA’s ecosocialists threaten to take away the seats of electeds who stand in the way of public power, by running their own socialist candidates against them32.

Climate organizations have called for climate strikes, phaseout of Fossil Fuels33, and the cancellation of new fossil fuel projects, but few have been able to make climate organizing a serious project for economic relief. The Green New Deal34, which many thinkers have described the BPRA as a statewide model for, is of course interested in not just passing climate laws but a just transition, affording relief to workers and people as we transform the economy to lean off fossil fuels. However, actually convincing our neighbors and our coworkers that we can achieve such relief for working people is the task ahead. Making climate a popular movement, not just in name, requires a serious commitment to economic relief first.

Endnotes

- Sheridan, Johan. 2023. “Billboard on 787 Roasts Hochul over BPRA.” NEWS10 ABC. March 22, 2023. https://www.news10.com/news/ny-capitol-news/kathy-hochul/billboard-on-787-roasts-hochul-over-bpra/.

- Hu, Akielly. 2023. “After a Four-Year Campaign, New York Says Yes to Publicly Owned Renewables.” Grist. May 4, 2023. https://grist.org/energy/after-a-four-year-campaign-new-york-says-yes-to-publicly-owned-renewables-strong/.

- Wang, Lawrence. 2023. “In New York State, Socialists Have Won a Landmark Victory for Green Jobs and Clean Public Power.” Jacobin.com. July 9, 2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/07/new-york-bpra-green-new-deal-public-renewable-energy.

- Taiwo, Olufemi. 2023. “You Can Win Bold Climate Laws in Your State.” Hammer & Hope. 2023. https://hammerandhope.org/article/climate-public-power-new-york.

- Featherstone, Liza. 2023. “New York Socialists Won Big on Climate. How Did It Happen?” In These Times. in-these-times. September 12, 2023. https://inthesetimes.com/article/new-york-build-public-renewables-socialists-climate.

- Ashley Dawson. 2023. “How to Win a Green New Deal in Your State.” The Nation. May 11, 2023. https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/dsa-new-york-build-public-renewables-act/.

- Patterson, Delia. 2018. “Public Power: A Rich History, a Bright Future | American Public Power Association.” Publicpower.org. February 15, 2018. https://www.publicpower.org/blog/public-power-rich-history-bright-future.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2021. “Why New York Needs Public Power.” YouTube. May 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRaX-LSjVUM.

- r/PropagandaPosters. 2020. “‘Vote the Socialist Ticket and Let the People Own the Light. Keep the Profit.’ – 1937 Local Election Poster Promoting the Building of a Municipal Power Plant in Reading, Pennsylvania.” Reddit. 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/PropagandaPosters/comments/fpgmbz/vote_the_socialist_ticket_and_let_the_people_own/.

- Magazine, Smithsonian, and Kat Eschner. 2017. “Here’s How FDR Explained Making Electricity Public.” Smithsonian Magazine. May 18, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/heres-how-fdr-explained-making-electricity-public-180963286/.

10.Tennessee Valley Authority. n.d. “TVA.” TVA.com. https://www.tva.com/.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2021. “Why New York Needs Public Power.” YouTube. May 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRaX-LSjVUM.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2020. “NYC-DSA Ecosocialists Interview East Flashbush Residents about the Con Edison Blackouts.” YouTube. August 7, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAFaJGPM5f8.

- Featherstone, Liza. 2023. “New York Socialists Won Big on Climate. How Did It Happen?” In These Times. in-these-times. September 12, 2023. https://inthesetimes.com/article/new-york-build-public-renewables-socialists-climate.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2020. “NYC-DSA Ecosocialists Interviews East Bronx Residents about Con Edison Power Outages.” YouTube. September 9, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-PXGULjtarY.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2020. “NYC-DSA Ecosocialists Interviews East Bronx Residents about Con Edison Power Outages.” YouTube. September 9, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-PXGULjtarY.

- Democratic Socialists of America. 2023. “BPRA: A Win in the Fight for a Green New Deal.” YouTube. May 23, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33JBBwM1P_Q.

- @nycdsaecosoc. 2020. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/B94w22cnY3U/?igsh=OHEwYWY4OHN3bDlu.

- Bussewitz, Cathy. 2018. “Report: One-Third of Households Struggle to Pay Energy Bills.” AP News. September 19, 2018. https://apnews.com/national-national-general-news-7c9aa47401664a6aa8914ec3e69e9298.

- @nycdsaecosoc. 2020b. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CAVOzvWgpmM/?igsh=Mjl6ODF0cWZ4ZnF3.

- King, Kate. 2020. “Long Power Outages after Isaias Spark Calls to Overhaul Utilities.” WSJ. The Wall Street Journal. August 19, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/long-power-outages-after-isaias-spark-calls-to-overhaul-utilities-11597858173

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2020a. “Public Power Hour: Episode 1 — an Interview with the Authors of ‘a Planet to Win.’” YouTube. May 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-V08b_9HhE.

- @nycdsaecosoc. 2020. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDg9VwNDE3W/?igsh=dnlrM2lrbDI2NXc0.

- @nycdsecosoc. 2020. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDjVgOwDUND/?igsh=MTFhbXRkbTJtcmRuZg==.

- Wang, Lawrence. 2023. “In New York State, Socialists Have Won a Landmark Victory for Green Jobs and Clean Public Power.” Jacobin.com. July 9, 2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/07/new-york-bpra-green-new-deal-public-renewable-energy.

- Wang, Lawrence. 2023. “In New York State, Socialists Have Won a Landmark Victory for Green Jobs and Clean Public Power.” Jacobin.com. July 9, 2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/07/new-york-bpra-green-new-deal-public-renewable-energy.

- “Stats and Facts | American Public Power Association.” n.d. Www.publicpower.org. https://www.publicpower.org/public-power/stats-and-facts.

- NYC Democratic Socialists of America 2021a. “In the Shadow of Fossil Fuels.” YouTube. May 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AbFCedvjLbA.

- “‘Asthma Alley’: Why Minorities Bear Burden of Pollution Inequity Caused by White People.” n.d. SOUTH BRONX UNITE. https://www.southbronxunite.org/press-and-media/asthma-alley-why-minorities-bear-burden-of-pollution-inequity-caused-by-white-people.

- Ashley Dawson. 2023. “How to Win a Green New Deal in Your State.” The Nation. May 11, 2023. https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/dsa-new-york-build-public-renewables-act/.

- “LibGuides: Climate Change and Environmental Law Guide: NY State Climate Initiatives.” 2019. Brooklaw.edu. 2019. https://guides.brooklaw.edu/climate/NY_State_climate_initiatives.

- New York City Democratic Socialists of America. 2019. “🌹⚡Publicpower.nyc – Join the Fight for #PublicPower in New York State!” YouTube. October 1, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ww9dBKXJC5M.

- Featherstone, Liza. 2023. “New York Socialists Won Big on Climate. How Did It Happen?” In These Times. in-these-times. September 12, 2023. https://inthesetimes.com/article/new-york-build-public-renewables-socialists-climate.

31.Featherstone, Liza. 2022. “Why This N.Y Socialist Is Running on Climate.” The Nation. 2022. June 21, 2022. https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/sarahana-shrestha-interview/.

- NYC Democratic Socialists of America. 2021b. “Why New York Needs Public Power.” YouTube. May 27, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRaX-LSjVUM.

- Featherstone, Liza. 2023. “New York Socialists Won Big on Climate. How Did It Happen?” In These Times. in-these-times. September 12, 2023. https://inthesetimes.com/article/new-york-build-public-renewables-socialists-climate.

- “350.org: A Global Campaign to Confront the Climate Crisis.” n.d. 350. https://350.org/?r=US&c=NA.

- “What Is the Green New Deal?” n.d. Sunrise Movement. https://www.sunrisemovement.org/green-new-deal/.

Primary Sources:

Approach: I feel that my secondary sources offer a range of perspectives on the history of energy justice, energy democracy, public power projects, New York environmental organizations, and labor and environment scholarship. While I am sure there are primary sources that might be helpful from various perspectives and time periods, I want to start with primary sources that are directly about the BPRA (Build Public Renewables Act) during the time period of 2019 (when it was launched) to now. This allows me to get an understanding of the fundamental facts, reactions, and debates around the BPRA. Once I have that I can try to explore and see what other primary sources to reference. As I mentioned in my site description, I am very interested in three things; how this win even happened/how did people organize for it, how will it be enforced, and why labor and climate organizing must be intertwined. For the sake of this assignment, I will mostly focus on the primary sources that share interviews and detailed timelines about how the act came to be.

1. Build Public Renewables Act Senate Assembly Legislation (pages 115-143), February 1, 2023, State of New York, Senate-Assembly https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2023/s4006c#page=115

The actual legislation is interesting to read. The BPRA is considered an amendment to the Public Authorities Law. The law details the various deadlines for New York state, through the NYPA (New York Public Authority) to implement, defines terms like renewable energy and decarbonization (“eliminating all on-site combustion of fossil-fuels and associated co-pollutants with the exception of back-up emergency generators”). As I do more research, I plan to reference the language of the legislation.

2. “After a four-year campaign, New York says yes to publicly owned renewables”, Akielly Hu, Grist Magazine, May 4, 2023

Grist is a prominent environmental journalism outlet and their article was one of the top hits when googling the BPRA. The article feels like an essential understanding of the base implications of the law, who was involved in pushing for it and what it might inspire with other environmental organizations in other states. The article also interviews a key actor in this law’s passing, Sarahana Shrestha, state assembly woman in New York who was key to pushing for the act. There is a good quote from Shresta in the article, stating that the BPRA addresses, “fundamental questions about who should own energy, who should serve energy, at what cost, and what kind of energy should we be making, and who should be deciding those things.” While it is a wordy quote, I think it is an easy way to understand what questions are at stake when moving from a private model to public ownership.

3. “The Problem with New York’s Public Power Campaign — and How to Fix It”, Matt Huber, Fred Stafford, July 30, 2022, The Intercept

https://theintercept.com/2022/07/23/new-york-build-public-renewables-act/

I wanted to include this article because it provides a more critical take on the BPRA and also highlights some of the obstacles to getting the act passed including how it failed to pass the State Assembly twice in 2020 and 2021. While the article was published before the bill did finally end up getting passed, I know from personal communication with the author Matt Huber that he still has some critiques about the process and the bill itself as it stands. Fleshing out some of these critiques can help me include in my report possible hiccups and areas of improvement that future bills in other states can learn from.

4. “Opinion: NY’s climate progress is failing. A new plan for public power can fix it.”, Julia Salazar, Sarahana Shrestha, July 27, 2024, City & State New York.

I chose this article because it is published in a local newspaper and is also written by two state assembly members who were key to passing the BPRA. They address us more recently, in the summer of 2024, to call out NY’s Governor Hochul for the lack of concrete progress in enforcing the BPRA. They share that there has been minimal transparency in the planning process and no public commitments to build clean energy, despite the law requiring such benchmarks. The article reads as a public record or public statement issued by elected officials calling out the Governor.

5. “Bulletin 134: A Public Power Victory in New York State – Build Public Renewables!”, June 2, 2023, Trade Unions for Energy Democracy website.

According to their website, Trade Unions for Energy Democracy (TUED) is a growing global network of over 120 unions and close allies working to advance democratic control and social ownership of energy. Partners include the CUNY union and the Rutgers Faculty Union. This article then focuses on the BPRA, praising its accomplishment and reflecting on how public power reduces the cost of utilities for low-income residents because there is no profit incentive like there is for companies like ConEdison or PSE&G.

6. “How New York’s Democratic Socialists Brought Unions Around to Public Renewables”, The American Prospect magazine, June 19, 2023. https://prospect.org/environment/2023-06-19-new-york-democratic-socialists-unions-public-renewables/

I chose this article because it focuses on the relationship between the organizers of the BPRA and labor unions. The article charts how at first many unions were opposed to the idea but with organizing, building relationships, and prioritizing labor protections, more were won over. I think that gathering more information to get clarity on the labor aspect of the law will be an important next step during my research for this project.

7. “Report: One-third of households struggle to pay energy bills”, Cathay Bussewitz, September 19, 2018, AP News.

https://apnews.com/national-national-general-news-7c9aa47401664a6aa8914ec3e69e9298

I chose this article because it was cited in the Grist article. I wanted to follow some of the citations for statistics on energy bills and racial justice. I think this article is important because it focuses on some prominent statistics that are often brought up in discussing this bill. The article states that nearly a third of U.S households have trouble paying their energy bill, disproportionately racial minorities.

8. “A Grid that Never Sleeps: Awakening New York City’s Renewable Potential”, Public Power NY Report, October 2024. https://publicpowerny.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NYPA-NYC-Position-Paper.pdf

This is an original report created by the Public Power NY coalition, which is the primary group that fought for the BPRA. It is the latest of several relevant reports created by community groups that detail the importance of the BPRA. This report focuses on the future of the BPRA, how to implement it, advocates for more renewable projects to be implemented in downstate New York and not just upstate New York. The report highlights some intra-New York considerations I hadn’t thought of before. I think understanding the specifics of how organizers want things to be implemented now is important.

9. “You Can Win Bold Climate Laws in Your State”, Summer 2023, Hammer & Hope Magazine, https://hammerandhope.org/article/climate-public-power-new-york

I chose this article because I was interested in the interview of actual organizers who led the campaign for the BPRA. The interviewees answer questions about their own political perspectives, the connection between the BPRA and racial justice, and situate the win amongst many other organizing efforts across the country. I am interested in these interviews to really understand what motivated people to organize for this act.

10. “New York Socialists Won Big On Climate, How Did It Happen?”, September 12, 2023, In These Times Magazine. https://inthesetimes.com/article/new-york-build-public-renewables-socialists-climate

I chose this article because it not only includes interviews with organizers behind the BPRA, but also provides a history of similar climate bills in other states. The article provides a sort of literature review of various efforts for public power and climate labor legislation such as Illinois’ 2021 labor-led Climate and Equitable Jobs Act. The article also does a really excellent job of pinpointing a timeline of events to give context to the win. I noticed that multiple articles (including this one) have placed the BPRA in the context of Biden passing the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, providing direct funding for any public agency that builds renewable energy. The IRA helped the BPRA pass more smoothly. Reading these multiple articles about the act is definitely helpful for me to internalize some of the key important points in the story. A lot of the articles also pay tribute to FDR’s creation of the New York Public Authority.

Primary Source Analysis

“Billboard on 787 roasts Hochul over BPRA”, News 10 ABC, Johan Sheridan, March 22, 2023, https://www.news10.com/news/ny-capitol-news/kathy-hochul/billboard-on-787-roasts-hochul-over-bpra/

News 10 ABC is a local news channel for Albany, New York, affiliated with the mainstream media giant ABC. This article is tagged under “Hochul Administration” referring to Kathy Hochul, the first female governor of New York State, who was elected in 2021 as a Democrat and will hold her seat till 2026. This article, though it is in a mainstream media publication, takes a slightly positive view of the organizations pushing for the BPRA and their power, a slightly critical view of Governor Kathy Hochul’s administration’s climate policy, interspersed with the neutral storytelling that is expected of the news outlet. I find this slightly positive view to be evidenced by the language in the headline, the direct quote from the Public Power NY coalition, and the analysis of the Data for Progress survey.

The headline of this article uses the word “roasts” to describe the impact of the billboard that the Public Power NY coalition put up on the 787 Interstate highway. If the billboard was seen as not being effective, or the messaging not clear, then the reporter would likely not have chosen the word “roasts”. A roast implies not only that a statement was very critical and negative but that it was made with a level of power and boldness, and often clever rhetoric. The article headline also highlights what activists on the ground would want them to highlight, which is the bill that they are trying to pass, BPRA. By Including their target, their bill, and placing their billboard as an effective attack on Hochul, the headline implies a level of power on the part of the environmental coalition. The article then also serves to raise to public audiences an interesting headline about a public official getting roasted, to then lead them to read about the BPRA, and learn what it is, which arguably is the most important thing for the coalition to do: communicate with those who don’t know about the bill yet but might be favorable. The headline is placed next to/ under the picture of the actual billboard. When reading the headline with the billboard, the billboard itself looks clever, well crafted, and powerful. The art is effective, showing a hand with solar panels and wind turbines held in it. The slogan is clear and simple, putting the number of New Yorkers who want public renewables over the number of people who voted for Hochul, implying that Hochul can or will get voted out if she doesn’t support this bill, and support what New Yorkers want.

The article also includes a direct quote from the Public Power NY’s announcement of their billboard. By including this and not including any quote from someone in Hochul’s administration, the article empowers a direct voice of the environmental coalition with no direct oppositional voice. The quote is also a well chosen quote to depict the actual demands of Public Power NY, their reasoning for this billboard, and again underscores their anger and critique of Hochul. Activists of Public Power NY would likely appreciate this article because as many activists know, a public stunt like a protest or a sign is often done with the goal of media coverage. The billboard was already bold in its tone and an article that underscores that boldness and shows the seriousness of how organizers feel about this issue helps organizers get their public stunt more visibility. The article does not offer any critique of this quote, and instead ends on it. By ending there, and having the last words be from the coalition itself, we leave the article thinking about their message to Hochul and wonder what her next move will be.

Finally, the article details the Date For Progress survey which the Public Power NY coalition uses as the basis for their billboard statement. While mostly maintaining neutral, including pointing out that many people surveyed had never heard of the BPRA, the author does also mention that Hochul had won “by a much slimmer margin” than that 90% threshold of support. This discussion of the billboard’s credibility offers an analysis that readers can likely then agree that the billboard’s statement is credible. There is no harsh critique of the numbers used. By doing so, the billboard seems even more powerful and the messaging even more evocative and clever.

Secondary Sources:

1. Build Public Renewables Act Project Guayo, I. del (Iñigo del). Energy Justice and Energy Law. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2020. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/energy-justice-and-energy-law-9780198860754?cc=us&lang=en&

This book provides a quite recent review of energy justice in the context of law, energy poverty, and the UN Sustainability Goals. This book can offer a crucial framing of energy justice, energy rights, and the rights of communities to participate in decision making regarding energy projects. Uniquely, this book can provide historical context for landmark cases of enforcing energy regulation and how to protect our legal rights when navigating energy justice issues. The book covers a transnational framework of energy justice, from South America, to the Middle East, to the United States in the last few decades. Being able to take a broader look at the fight for energy justice can ground my project with the basic context of how different countries have approached this issue. When organizers and activists pushed to pass the BPRA (Build Public Renewables Act), it was because they had statistics that many New Yorkers were unable to make their utility payments each month. The goal was to help those who needed it most by raising the bar for us all, which is in tune with the theory of energy justice. This source can help me connect the dots between concepts of energy justice in the BPRA and across the world.

2. Barca, Stefania. “Laboring the Earth: Transnational Reflections on the Environmental History of Work.” Environmental History 19, no. 1 (2014): 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emt099.

This article offers an analysis of the intersection of work and nature, specifically those who work in environmentally destructive industries and their relationship to their work and to their environments over the last century. The article can provide a framing for a political and cultural framework around how environmental policies must be labor-friendly. The article offers a literature review of various Marxist thoughts on work and nature interspersed with real case studies of workers engaging with environmentalism in Italy, Mexico, and Brazil. Barca also references Andrew Hurley’s work on Gary, Indiana, overall connecting the dots between various studies of workers and environmental movements. This article can provide me with context to consider the critiques that some have had of the BPRA and its involvement and dialogue with workers.

3. Tomoiaga, Alin Simion, Salwa Ammar, and Christopher Freund. “Case Study on Renewable Energy in New York: Bridging the Gap between Promise and Reality.” International Journal of Energy Sector Management 15, no. 1 (2021): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJESM-02-2020-0016.

This article is focused on recent New York energy history and the path towards renewable energy. Since my project will dive into the history of the BPRA, it will be useful to read what people were thinking and where things were out before it was passed. The article suggests that environmental issues are tightly wrapped up with governmental politics in New York. While being clear about the role of politics, the study is highly scientific, offering a more mathematical and factual analysis of electric supply and energy modeling. While I am more interested in history, a scientific report focused on New York’s renewable energy feasibility is useful to reference.

4. Dick, Wesley Arden. “When Dans Weren’t Damned: The Public Power Crusade and Visions of the Good Life in the Pacific Northwest in the 1930s.” Environmental Review 13, no. 3/4 (1989): 113–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/3984393.

Much of my research has pointed me to consider the public power movement of the 1930s New Deal era. After all, the NYPA (New York Power Authority) that has the administrative responsibility for the BPRA, was created by FDR in 1931. FDR established the NYPA as a model for public power. Understanding the full history of the BPRA requires an understanding of what initial models for public power looked like and the legacy of those models today. The author of this article argues that simply because there was an interest in public ownership did not necessarily mean that advocates were critical of capitalism, the American dream, or infinite growth. There was still a view of nature as a commodity, just a government owned commodity. This is interesting to consider and compare to today’s public;y owned power movements.

5. Cebul, Brent. “Creative Competition: Georgia Power, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Creation of a Rural Consumer Economy, 1934–1955.” The Journal of American History (Bloomington, Ind.) 105, no. 1 (2018): 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jay007.

Public scholars have lauded the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) as a positive model for public power ownership, a win of the New Deal that still exists and runs today, providing cheap public power for all. 60% of its workers are represented by unions, which is quite good especially for that part of the country. This article provides a history of the TVA, created in 1933 by FDR, allowing me to do a deeper dive into the history of publicly owned power through a concrete example. The article critiques the TVA’s history including its lack of opportunities for Black workers and exclusion of Black residents from the community model. Learning about the history of public power and racial discrimination is an important context for my project.

6. Huber, Matthew T. Lifeblood : Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816677856/lifeblood/

Huber’s book offers another angle for me to consider, which is to tell the story of the struggle for renewable energy policies through the story of our addiction to oil and gas over the last century. Our addiction to oil and our fetishization of oil in popular culture through slogans like “Drill, Baby, Drill” shows us that the hesitations towards a just transition in all aspects of energy use are quite deeply rooted and hard to challenge. Huber argues that as various politicians, companies, and lobbyists double down on championing the fossil fuel regime, there is probably no industry where the democratization of production is more necessary than energy. Huber argues that the biggest challenges to energy change are not technical but “cultural and political structures of feelings that have been produced through regimes of energy culture” (Huber, 169). This is an interesting framing that points out how there is a culture of fear that maybe any energy transition can result in energy scarcity, reduction of what people are allowed to do or how much energy each of us can use, etc. These fear mongering ideas of what a just transition can look like definitely stifle any major progress towards a just transition.

7. Carroll, William K. Regime of Obstruction : How Corporate Power Blocks Energy Democracy. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2021. https://www.aupress.ca/books/120293-regime-of-obstruction/

This book offers a study of the efforts from corporations to wield their power and block any campaigns for energy democracy in contemporary times. It can provide me a reference point to consider what actors might have organized against the BPRA and how they wielded their power. Honing on the idea of energy democracy, this book addresses both the power and politics of the fossil fuel industry and activism against that power. This book explains how corporations can quell movements and spread propaganda that paints fossil fuels as a positive backbone of our country that we must preserve.

8. Allen, Elizabeth, Hannah Lyons, and Jennie C Stephens. “Women’s Leadership in Renewable Transformation, Energy Justice and Energy Democracy: Redistributing Power.” Energy Research & Social Science 57 (2019): 101233-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101233.

This article researches gender in energy justice and energy democracy movements, particularly the role of women’s leadership in these spaces. The article focuses on two women-led non profit organizations that are advancing renewable energy transition in contemporary times. One organization is Grid Alternatives which is a solar installation workforce training organization, and the other is Mothers Out Front which is an advocacy organization. By considering the role of women in energy democracy and the theoretical understandings that the article offers, I can think about the role of gender and women’s leadership in the coalitions that fought for the BPRA.

9. Sze, Julie. Noxious New York : The Racial Politics of Urban Health and Environmental Justice. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007. https://direct.mit.edu/books/monograph/2798/Noxious-New-YorkThe-Racial-Politics-of-Urban

This book offers a deeper environmental justice history of New York that can allow me to draw any connections between the BPRA and other key environmental issues that are important to know about in New York. There is also a chapter in the book titled, “Power to the People? Deregulation and Environmental Justice Energy Activism” which documents planning board meetings, borough hearings, and community activism around energy policy in New York. The chapter highlights key community groups, landmark policies, federal offices, and key reports that were important in the 1980s to early 2000s in New York.

10. Roache, Kelly. “Energy Democracy in the Northeastern US: Case Studies from New York State.” In Climate Justice and Community Renewal, 1st ed., 222–35. Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429277146-15.

This chapter in a book about community climate organizing, is focused on energy democracy in New York in the late 1990s to early 2000s. This is helpful because it focuses on the democracy aspect which is important to the BPRA and it is focused on New York. The chapter analyzes efforts of the past to build renewables on a granular level of specific communities that tried to achieve community solar models. Roache argues that non profit organizations and houses of worship were central to these efforts while also adding a disclaimer that there is no one size fits all model for building renewable energy projects.

Image Analysis:

a

https://publicpowerny.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/CCP-Report-on-Public-Renewables.pdf

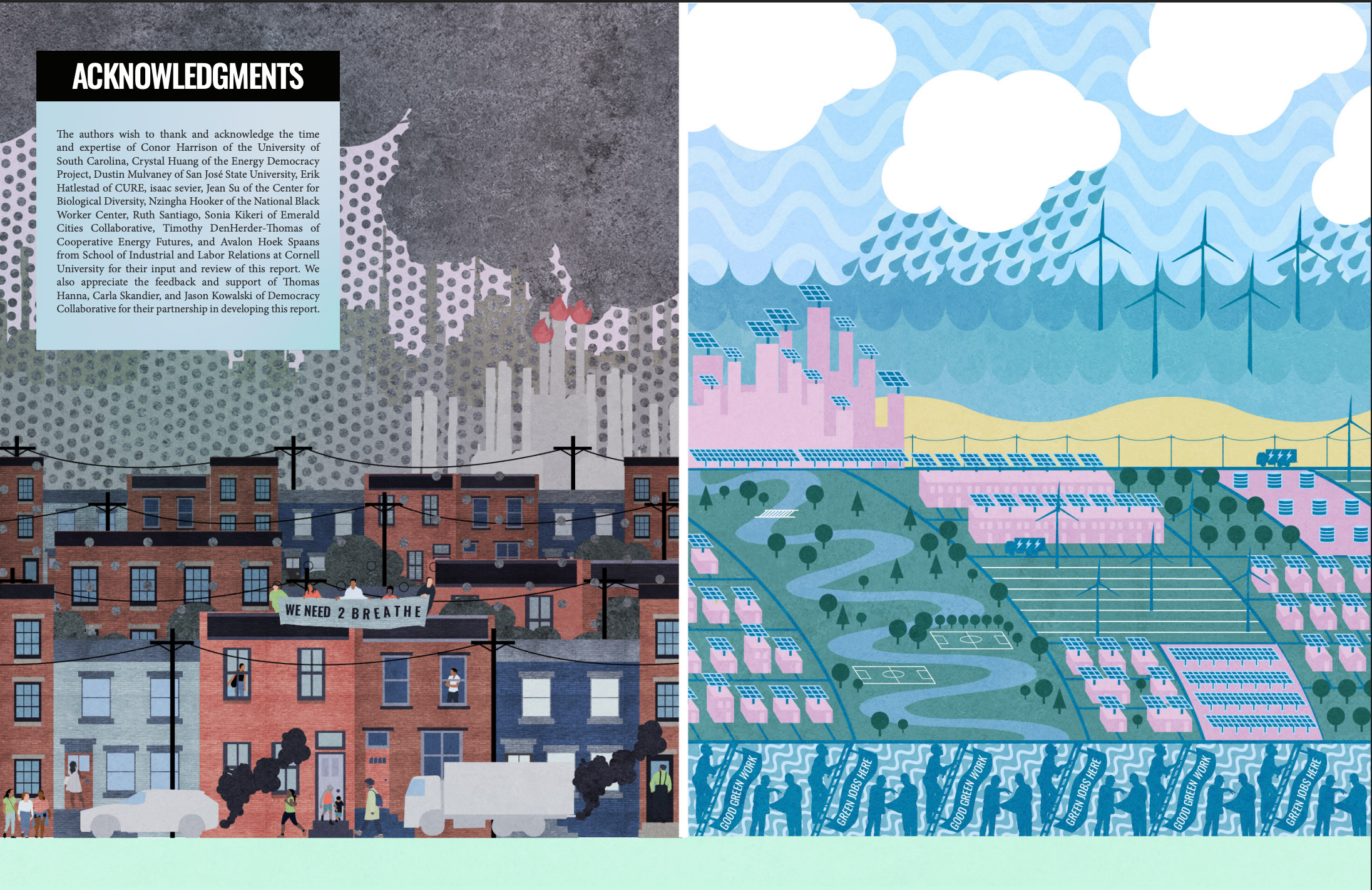

This image is designed by A.L McCullough as part of a report created by The Climate + Community Project and The Democracy Collaborative that advocates for the Build Public Renewables Act.

—

The contrast is undeniable. In one world we continue to live under an all consuming cloud of industrial exhaust. In the other world, clean white unblemished clouds tell us we are doing a good job- there are no puffs of pollution emitting from our energy sources-instead solar panels and windmills quietly and smoothly harness the power already around us. Trees dot the peripherals of a flowing river, every house and building and school is covered by solar panels. This graphic keys us into a before and after, asking us to identify which one we want- a dark gloomy polluted world, or a bright and abundant one. The graphic’s use of dark and bright contrast and other key details obviously promotes the future that the BPRA envisions over our current way of life under fossil fuel supremacy. A graphic made by someone who opposes the BPRA would look entirely different.

The use of color is what draws one’s attention first. Darkness smears over the first image; the neat coexistence of blue, green, pink, and yellow offers a calm antidote in the second. Color is the most effective feature of this image. Just off the bat, it is clear that one world is preferable to the other. We can almost taste, feel and smell the unnatural darkness of the industrial exhaust, just from the hues that the artist uses. The color also makes it clear that in the first image, we cannot separate ourselves from this exhaust. The dark clouds fade and blend into the air that people in the image breathe. The second image is a pure contrast to the chaos of the first, the light colors stand out starkly against the dark colors of the first image. This evokes positive feelings with clean energy but also a moral clarity of light prevailing over darkness.

The people in the first image look busy and immersed in their world, with the exception of the five people on the rooftop holding a “WE NEED 2 BREATHE” banner. The people all look recognizable, either people alone arriving home, in their apartments, heading on a run after work maybe, or talking in a small group of friends. Their clothes feel familiar and they seem in motion, partaking in their mundane everyday routines. The people holding the banner, however, are choosing to speak despite a busy world around them that seems to not notice them. Yet their mission seems important, with the factory looming behind, it seems that they are acknowledging something very real that is happening in real time. The graphic shows us a world that is very much our current world. One man who looks like a utility worker in a bright green vest seems to be standing at his door looking at the protestors and thinking about their message. The second image centers these workers, who ultimately will be the ones to lead us into a green future by constructing solar panels and windmills to replace pollutive factories. They exist in the bottom section of the image with labels reading “GREEN JOBS HERE”, “GOOD GREEN WORK”. There is a unity in the second image that is lacking in the first, people seem to be on the same page with a plan and vision for clean energy that they are executing.

Cars in the first image are polluting big gusts of dark black clouds that drift upwards to the windows of apartment dwellers. They are run by oil and gas. The second image makes a point of painting charging symbols on the two small trucks tucked into the landscape, not taking much space, not producing any clouds of pollution. Two big cars being on a small block in this city implies many many other cars polluting across the city. In the second picture, you would imagine with scale we would see more cars, but we only see two as well. The fact that there are so few cars implies that this world is less car reliant, yet a lack of imagery of public transit or some other alternate green transit leaves some things up for our imagination. The artist is less interested in depicting exactly what our world would look like (this image is certainly not detailed enough to be a blueprint for change) but it tickles our imagination just enough to desire something better than dark clouds and polluted air.

The graphic articulates a past and present of our country, old Pre-war apartment buildings, factories that have existed for decades, and people (us) who are continuing to live in a fossil fuel built world. The graphic also depicts a future that we can choose, that the people in the first image can herald into being. This graphic uses dark and light color to leave no doubt about which world is better. The color guides a reading of other features in the graphic. The people’s disorganization in the first picture feels like it’s not enough compared to the gravity of the crisis they are living in. While the second image is still sort of imaginary and dreamlike with its baby blues and soft pinks, the graphic urges us to entertain our desires for that world. The graphic argues that we should be disturbed by our current world and we should and can imagine something better. The workers at the bottom with their message about good green work and the charging symbols on the cars makes that second world seem more real and grounded. It is not just a dream but it is possible.

Data Analysis:

Oral Interviews:

Video Story:

My video covers the history of public power in the US in the context of current calls for public power through the Build Public Renewables Act in NY State.