Eternal grief in City of God: socio-environmental inequalities connecting the flood disasters of 1966 and 1996 in Rio de Janeiro

by C.M. Freitas

Site Description:

This report focuses on the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It presents the history of two impactful moments: the floods of the 1960’s (1966-1967), and the flood of 1996. This study aims at understanding how these events affected the population unevenly, with special attention to the categories of race and social class. The research is based on secondary data, as well as primary data from local media and a summary report prepared by a range of civil society actors in the aftermath of 1996’s flood to guide public policy solutions for floods in Rio. The main questions guiding this study are: 1) how are the floods of 1966-1967 related to the flood of 1996? 2) How has society recognized and portrayed the racial and social inequalities that marked these events? 3) What were the political reactions to these events (coming both from government administrations as well as the civil society)? This project presents an original contribution to the studies of environmental justice history, particularly in Brazil, as it brings the analysis of primary data about the 1996 flood to be compared with the existing historical studies on the 1960’s floods. Given that extreme climate events such as rainstorms tend to become more frequent in Rio de Janeiro’s future, the analysis of historical processes related with flooding allows for a more complex understanding of how these events have not only been shaping the city and its urban development, but also its political landscape.

Screenshot of Michael Jackson’s video clip “They don’t care about us” (Brazil version) recorded partially in favela Santa Marta in Rio de Janeiro and partially in Pelourinho, Salvador. Photo credits: Reproduction / YouTube.

Introduction

On the Sunday of February 11, 1996, despite protests from local elites, Michael Jackson recorded scenes of the videoclip for his song “They don’t care about us” from atop a hill called Santa Marta in Rio de Janeiro. On the video, we can see the city of Rio and the ocean behind his back, lit by a cloudy sky, as he looks to the camera singing these words: “I’m tired of being the victim of hate / You’re ripping me off my pride / Oh, for God’s sake / I look to heaven to fulfill its prophecy / Set me free.” As the megastar sang, the cloudy sky behind him was preparing a storm that would mark the history of the city. The following days, Rio would receive an amount of rain that hadn’t been seen in nearly 30 years (or “ever,” according to some reports). The most affected area was the West Zone, particularly the neighborhood Cidade de Deus (City of God), a favela located 20 miles away from the one visited by Michael Jackson. Many people (mostly children) would lose their lives as the neighborhood was entirely flooded. The local news covered the tragedy without mentioning an important fact: the neighborhood Cidade de Deus had been promoted by local authorities as an urban development solution to another huge flood disaster, which had happened thirty years before. Purportedly, the survivors of the 1966 flood were relocated from other areas of Rio to Cidade de Deus so that they would not have to face a flood tragedy again. But they did. This report traces the interconnections of these two floods in Rio de Janeiro.

Primary Sources:

O Globo (Newspaper)

Title: O Globo—Issues from February 11 to February 29, 1996. (1996, February). O Globo. Acervo Digital Jornal O Globo.

Link: https://oglobo.globo.com/acervo/.

Location: This source is available on Acervo Digital Jornal O Globo: https://oglobo.globo.com/acervo/.

Description: O Globo is one of the main newspapers from the city of Rio de Janeiro. Founded in 1925, it gave origin to Globo TV, the main TV broadcasting company of Brazil. I have analyzed the issues of O Globo from February 11 to February 29, 1996, following the news about: the flood and its political ramifications, Michael Jackson’s visit, and 1996’s carnival in the city of Rio. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Jornal do Brasil (Newspaper)

Title: Jornal do Brasil—Issues from February 11 to February 29, 1996. (1996, February). Jornal do Brasil. Google News.

Link: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=0qX8s2k1IRwC&dat=19960225&b_mode=2&hl=en.

Location: This source is available on Google News: https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=0qX8s2k1IRwC&dat=19960225&b_mode=2&hl=en.

Description: Jornal do Brasil is one of the main newspapers from the city of Rio de Janeiro. Founded in 1891, it is one of the most traditional newspapers of Brazil. I have analyzed the issues of Jornal do Brasil from February 11 to February 29, 1996, following the news about: the flood and its political ramifications, Michael Jackson’s visit, and 1996’s carnival in the city of Rio. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Folha de São Paulo (Newspaper)

Title: Folha de São Paulo—Issues from February 11 to December 31, 1996 – search for keywords such as “Cidade de Deus,” “enchente,” “Michael Jackson,” “favelado”. (1996). Folha de São Paulo. Acervo Folha.

Link: https://acervo.folha.uol.com.br/digital/.

Location: This source is available on Acervo Folha: https://acervo.folha.uol.com.br/digital/.

Description: Folha de São Paulo is one of the main newspapers from the state of São Paulo. Founded in 1921, it is one of main newspapers of Brazil. I have analyzed disparate news articles from Folha de São Paulo according to keyword search delimited within the year of 1996 (from February 11 to December 31). In this search, I was selecting news articles about: the flood (in Rio) and its political ramifications, Michael Jackson’s visit (to Rio), and 1996’s carnival in the city of Rio. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Revista Manchete, 02/24/1996 (Magazine)

Title: Revista Manchete (1996, February 24). Revista Manchete, 1996(2290), 100. Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira.

Link: https://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=004120&pagfis=1.

Location: This source is available on Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira. https://memoria.bn.gov.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=004120&pagfis=1.

Description: Manchete was a weekly magazine focused on social life and culture, covering mainly Rio de Janeiro, but also other cities in Brazil. In this issue, from February 24, 1996, the magazine covered exclusively the carnival celebrations in Rio and in other cities from Brazil. On pages 43-44, it shows pictures of the presentation from Mocidade de Jacarepaguá, a samba school from Cidade de Deus that skipped the official presentation due to mourning the death of 29 of its members due to the flood that had happened days before. Instead of an official presentation, the members walked in silence while crying. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Enchente (Documentary Film)

Title: Pecly, J., & Silva, P. (Directors). (2011, January 19). Enchente [Documentary].

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gyiEBWrzqM.

Location: This source is available on the video producing company’s page on YouTube (CAVIDEO):https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gyiEBWrzqM.

Description: This source is a documentary video produced with original footage from residents from Cidade de Deus neighborhood during the flood of 1996, as well as imaged ceded by Globo TV, and original interviews with residents at the time that the documentary was produced in 2010. This source helped me understand how this flood impacted the neighborhood of Cidade de Deus, according to the perspective of its residents. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Globo Reporter 02/16/1996 (TV Broadcast)

Title: Globo Reporter 02/16/1996—Chuvas no Rio de Janeiro (No. 02/16/1996). (1996, February 16). [Documentary]. In Globo Reporter. Globo TV.

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dnavn4WnYaE.

Location: This source is available on a collector’s page on YouTube (Pedro Janov e seu arquivo de videos): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dnavn4WnYaE.

Description: This source consists of the weekly news TV broadcast show called “Globo Reporter” produced by the most mainstream TV channel in Brazil during the week of the 1996 flood. It includes the main video footage of this event done by Brazilian TV, including helicopter images, interviews with affected residents from several neighborhoods, and a short interview with Rio’s mayor at the time, Cesar Maia. This source helps me understand the flood of 1996 by watching an overview of how local mainstream TV reported this. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Jornal Nacional 02/14/1996 to 02/17/1996 (TV Broadcast)

Title: Jornal Nacional 02/14/1996 to 02/17/1996—Chuvas no Rio de Janeiro (No. 02/14/1996 to 02/17/1996). (1996, February). [TV news broadcast]. In Jornal Nacional. Globo TV.

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbWGXVuoygU.

Location: This source is available on a collector’s page on YouTube (Pedro Janov e seu arquivo de videos): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbWGXVuoygU.

Description: This source consists of the daily news TV broadcast show called “Jornal Nacional” produced by the most mainstream TV channel in Brazil on February 14, 1996. It includes video footage of this event done by Brazilian TV, including helicopter images, and interviews with affected residents from several neighborhoods. This source helps me understand the flood of 1996 by watching an overview of how local mainstream TV reported this. This source contributes to the primary data analysis of this report.

Rio on Watch (Online News Article)

Title: Conceição, G. da, & Santos, L. (2024, January 22). Meeting of the Waters in City of God: Local Project Strengthens Identity and Salvages Memory of the Community’s Rivers (K. Alvito, Trans.). Rio on Watch.

Link: https://rioonwatch.org/?p=77172.

Location: This source is available on Rio on Watch digital magazine: https://rioonwatch.org/?p=77172.

Description: This is an online news article published in the digital magazine Rio on Watch. The article was produced by the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) Youth Working Group as a final article from the course “Climate Justice in Community Journalism: From Pitching to Writing,” developed in partnership between Rio on Watch and the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University. This source presents the history of Cidade de Deus and its relationship with surrounding rivers, through the views of the neighborhood’s youth environmental advocates of 2024.

Tormentas Cariocas (Report)

Title: Rosa, L.P., & Lacerda, W.A. (Coordination) (1997). Tormentas cariocas: seminário prevenção e controle dos efeitos dos temporais no Rio de Janeiro. COPPE/UFRJ.

Link: https://coepbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TORMENTAS-CARIOCAS.-Seminario-Prevencao-e-Controle-dos-Efeitos-dos-Temporais-no-Rio-de-Janeiro.pdf.

Location: This source is available on COEP website: https://coepbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TORMENTAS-CARIOCAS.-Seminario-Prevencao-e-Controle-dos-Efeitos-dos-Temporais-no-Rio-de-Janeiro.pdf.

Description: This document is a report based on a seminar organized in February 1996 to promote a civil society response to the tragedy that had happened weeks before. The seminar was organized by COEP (an NGO that worked as a network of community groups) and COPPE (School of Engineering of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), together with other groups of interest (local media, public authorities) to discuss possible solutions to avoid another tragedy like that to happen again.

Memoria Globo – Enchentes no Rio – 1966 (Blog)

Title: Memória Globo. (2021, October 29). Enchentes no Rio—1966. Memória Globo.

Link: https://memoriaglobo.globo.com/jornalismo/coberturas/enchentes-no-rio-1966/noticia/enchentes-no-rio-1966.ghtml.

Location: This source is available on the website Memoria Globo, produced by Globo TV: https://memoriaglobo.globo.com/jornalismo/coberturas/enchentes-no-rio-1966/noticia/enchentes-no-rio-1966.ghtml.

Description: This source consists of a blog article and a video containing original footage of the 1966 flood, as well as an interview with a Globo TV employee who explains how important this event was to consolidate the audience of that TV channel, which was small and irrelevant at that time, but grew to become the largest media institution of Brazil (according to this interview, thanks to Globo’s coverage of the 1966 flood). This source helps me understand how mainstream media in Brazil consolidated their journalistic activities by portraying disasters.

“They don’t care about us” (Brazil version) by Michael Jackson (Music Video)

Title: Jackson, M. (1996). Michael Jackson—They Don’t Care About Us (Brazil Version) [Music Video].

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNJL6nfu__Q.

Location: This source is available on the artist’s page on YouTube (Michael Jackson): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNJL6nfu__Q.

Description: This is the official music video for the song “They don’t care about us” by Michael Jackson, shot in two Brazilian locations: favela Santa Marta in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and Pelourinho, in the city of Salvador. Due to reports on Brazilian newspapers and TV broadcasting, I learned that the video filming atop Santa Marta hill occurred on the Sunday of February 11, 1996. This source helped me analyze the weather conditions of that day through video footage.

Secondary Sources:

Dereczynski, C. P., R. N. Calado, and A. B. Barros. “Chuvas Extremas No Município Do Rio de Janeiro: Histórico a Partir Do Século XIX.” Anuário Do Instituto de Geociências – UFRJ 40, no. 2 (June 10, 2017): 17–30. https://doi.org/10.11137/2017_2_17_30.

This article analyzes all the events of extreme rain registered in the city of Rio de Janeiro between 1881 and 1996. To evaluate this period, the researchers accessed two sets of historical data on pluviometric information, summing a total of 63 years of complete rain data for every day. The methodology included a pre-selection of all events that had more than 100 mm of rain in one day, totalizing 100 events. Of those, 82 were selected due to the level of damage caused. Considering the 63 years of data, the average occurrence of extreme rain events in the city of Rio is 1.3 events per year. Once the events were selected, researchers looked for news articles from several newspapers in the city to collect data on reported damages from the rains. One of the conclusions is the constant presence of discussion in news articles on who should bear the responsibility for the damages, among local, state, and federal government entities (until 1960 Rio de Janeiro was the capital of Brazil, from 1960 to 1975, it has been a city-state called Estado da Guanabara, and since 1975 it is the capital city of the state of Rio de Janeiro). According to the study, the most impactful flood events were the ones in January 1966, February 1988, and February 1996. This article contributes significantly to my project, as it demonstrates that the events of 1966 and 1996, which I am analyzing, are among the most impactful in the vast history of floods in Rio de Janeiro.

Maia, Andréa Casa Nova, and Lise Sedrez. “Narrativas de Um Dilúvio Carioca: Memória e Natureza Na Grande Enchente de 1966.” História Oral 14, no. 2 (October 22, 2012). https://doi.org/10.51880/ho.v14i2.239.

This article uses the methodology of oral history to analyze the social impact of the mega flood of 1966 in the city of Rio de Janeiro – an event that left around 250 people dead and around 50,000 people homeless. The researchers started the study with the community around the catholic church located at Praça da Bandeira, one of the main locations related with the flood in people’s memory, as it is a central point that connects several zones of the city. During the flood, a solidarity network was formed by local institutions such as the church and local schools. The displaced families (who came from several “morros” – hills occupied by favelas such as Rocinha, Morro do São Carlos, and Morro do Borel, as well as other neighborhoods) were sheltered in a stadium called Maracanãzinho. From there, they were taken to live in a new neighborhood built by the municipal government in a far-away region of the city: Cidade de Deus (City of God) in the then semi-rural West Zone. The interviewees in this research project are women who moved to Cidade de Deus after the floods. They comment on the lack of infrastructure in the neighborhood when families were moved there, the difficulties to socialize as there were people from several different places moved to that neighborhood (“different cultures”), and that the area was very inaccessible with scarce transportation infrastructure to go to work in the South Zone of the city (where families came from). The authors highlight the gender hierarchies and their inversion during the time of disasters, as well as class relations in this context. It is implied that the floods were seen by the local government as an opportunity to remove families from favelas in the richer part of the city (South Zone) to the semi-rural area that was about to be urbanized (West Zone), in both ways benefiting from real estate speculation and economic gains from urban development projects. This article contributes immensely to my project, as it demonstrates how the flood of 1966 contributed to populate the neighborhood Cidade de Deus, and how that process of population transfer was felt by the people who had to move.

Maia, Andréa Casa Nova, and Vicente Saul Moreira dos Santos. Rio, cidade submersa: Imagem e História das inundações cariocas. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Onirá artes gráfica, 2025. https://www.oniraeditora.com.br/riocidadesubmersa.pdf.

This book presents the history of floods in the city of Rio de Janeiro, from the early 1900’s to the late 1960’s. The methodology used is the analysis of newspaper/magazine articles and cartoons, complemented by a few oral history interviews. This book, published in April 2025, provides a turning point to think urban planning in Rio de Janeiro, as it looks at the history of the city from the angle of flood events and how different sectors of society have been building century-old discourses about flooding. As someone who is not from Rio de Janeiro, I was surprised to learn about how old some flood-related discourses are and how little they have changed from events that happened decades (and in some cases, more than a century) ago. This source has offered great insight for my project, particularly chapter 3, which presents the devastating floods of 1966 and 1967 in details as they were reported by the local press.

Malta, Fernanda Siqueira, Eduarda Marques Da Costa, and Alessandra Magrini. “Índice de Vulnerabilidade Socioambiental: Uma Proposta Metodológica Utilizando o Caso Do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.” Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 22, no. 12 (December 2017): 3933–44. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320172212.25032017.

This is a quantitative study combining data from Brazil’s census, Geo-Rio Foundation, and Rio de Janeiro state’s Public Safety Institute. It assesses the level of socio-environmental vulnerability of the population in all neighborhoods and regional units of the city of Rio de Janeiro. This was done through the development of an index that includes social, economic, and urban infrastructure processes that connect quality of life precarity (labor, education, income, sanitation, mobility) with environmental, health, and public safety conditions. This contributes to my project as it presents a series of indicators that can be analyzed to assess social-environmental vulnerability.

Medeiros, Felipe Souza De, Mariza Reis Almeida, Márcio Araújo De Souza, and Kátia Eliane Santos Avelar. “A Urbanização do Município do Rio De Janeiro: Uma Visão Sobre as Enchentes e Inundações.” Sustentare 4, no. 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5892/st.v4i1.6164.

This article traces back the history of the city of Rio de Janeiro’s urbanization to understand the reasons behind so many flooding events in the city. It identifies an urbanization model based on economic growth as the reason for the city’s development to have happened in the way that it. More specifically, it explains the concentration of the city around Guanabara Bay, due to the transportation networks and commerce that were present in this area. Due to a need to connect this area to other parts through transportation networks, the city became more and more paved. Because of this development style, local ecosystems were deteriorated, causing the environmental issues that are ubiquitous today, particularly flood events. This article contributes to my project as it connects the flood problems with patterns in the city’s historical urban development.

Milanez, Bruno, and Igor Ferraz Fonseca. “Justiça Climática e Eventos Climáticos Extremos: Uma Análise da Percepção Social no Brasil.” Revista Terceiro Incluído Vol. 1., no. No. 2. (2011): 82–100. https://doi.org/10.5216/teri.v1i2.17842.

This study presents the origins of the term “climate justice” (from a Brazilian perspective) and analyses news media reports from two flood events in the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. It concludes that even though events permeated by climate injustice were already perceptible in Brazil at the time (2009/2010), the discourse of climate justice had not yet been adopted in the country (by stakeholders such as media outlets, society in general, and the affected communities). This article contributes to my project as it brings the perspective of climate justice as a new discourse about floods in Brazilian cities, in light of climate change discussions that are proper of the twenty-first century.

Sedrez, Lise, and Andrea Casa Nova Maia. “Enchentes que Destroem, Enchentes que Constroem: Natureza e Memória da Cidade de Deus Nas Chuvas de 1966 e 1967*.” Revista do Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, no. 8 (2014): 183–200. http://wpro.rio.rj.gov.br/revistaagcrj/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/e08_a10.pdf.

This article, published in the journal of Rio de Janeiro’s City Archive, presents the history of the floods of 1966 and 1967, as they affected the neighborhood Cidade de Deus (City of God). The main argument of this article is that floods are not only “destroying forces,” they are also “constructing forces” as they end up influencing and determining action toward urban re-development which ultimately changes the landscape of the city. The authors see the neighborhood of Cidade de Deus as a space that was created by the 1966 and 1967 flood. Therefore, they see the flood as a process of urban development. This study is based on oral history interviews and it attempts at providing the perspective of vulnerable groups (poorer people who were affected by the flood) into history, and particularly environmental history. It contributes to my project significantly as it sheds light on how the floods and the process of moving were felt by people from poorer areas who ended being relocated to Cidade de Deus. This source helped me understand how the development of Cidade de Deus is intimately connected with the mega floods from the 1960’s.

Souza Santos, Andrea, Suzana Kahn Ribeiro, and Victor Hugo Souza De Abreu. “Addressing Climate Change in Brazil: Is Rio de Janeiro City Acting on Adaptation Strategies?” In 2020 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Energy, Environment and Climate Change (ICUE), 1–11. Pattaya, Thailand: IEEE, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUE49301.2020.9307010.

This article presents an institutionalist perspective on climate adaptation in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The study reviews literature on climate adaptation, highlighting the main risk factors for cities/urban environments in Brazil, and specifically for Rio. Cities, or urban spaces, are considered more prone to vulnerability, particularly if they are on the coast. A vulnerability factor for Rio de Janeiro, for example, is rising sea level – which may affect more than 10% of the city’s area. Regarding disasters, the main risks for Brazilian cities include flash floods, landslides, and droughts. In the case of Rio, the occurrence of extreme rain events is recurrent in the city’s history, and an increase in these events has been observed. The impact of climate change in Brazilian coastal cities has direct effects on ecosystems and populations; as well as indirect effects, as it impacts the provision of services such as sanitation, health, and transportation. The level of social vulnerability in Rio is high due to its low Human Development Index, in addition to high population density. In face of all these risks, the authors observe the necessity for the municipality to develop and implement an adaptation plan. They evaluate the plans and actions the city has undertaken in that field, including individual indicators of resilience assessment, resilient youth program, reuse of rainwater project, urban reforestation programs, and heat waves and heat islands assessment. The authors also evaluate the City of Rio de Janeiro’s Climate Adaptation Plan. They conclude that the guidelines proposed by the plan can make the city more resilient, however, the local governance aspect lacks transparency and accountability on the execution of the plan. This article contributes to my project as it shows how different sectors of Rio de Janeiro (engineering schools, local administration) understand and try to resolve the problem of climate adaptation (including floods) currently and into the future.

Swyngedouw, Erik, and Nikolas C Heynen. “Urban Political Ecology, Justice and the Politics of Scale.” Antipode 35, no. 5 (November 2003): 898–918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00364.x.

This is a theoretical article that develops the conceptual grounds for the application of political ecology in the field of urban studies. The authors start by connecting the frameworks of political economy with ecology by demonstrating that matters of environment, nature, and land have been the focus of historical-materialist scholars for a long time, particularly in the field of urbanization: “‘environmental’ issues have been central to urban change and urban politics for at least a century, if not longer.” (Swyngedouw and Heynen, 2003). Then, they connect the economic/ecological process of urbanization to the social/cultural process that accompanies it, asserting that “the environment of the city – both social and physical – is the result of a historical-geographic process of the urbanization of nature” (Swyngedouw and Heynen, 2003). Following this logic of interconnectedness, they explain that “there is no such a thing as an unsustainable city in general” (Swyngedouw and Heynen, 2003). Instead, they affirm, cities are made by interconnected urban and environmental processes that impact some groups negatively while impacting other groups positively. Hence, the aspect of (in)justice is embedded in these multiple power relations. And the power that shapes these processes is spread throughout several scales, through global-local processes and interconnected networks. Once all of these relations are established, the authors reflect on the need for radical geographers to understand the natural metabolisms of cities, to point more accurately to how these physical phenomena are “socially appropriated to produce environments that embody and reflect positions of social power” (Swyngedouw and Heynen, 2003). Reflecting on the “urbanization of nature” the authors discuss the role of ideologies about nature in the urban-making processes, reminding that the modern conception of the separation between human and nature is but an ideology that molds these processes. Reflecting on the “production of urban nature” they move further with the idea that “all kinds of environments are socially produced” and that “human activity cannot be viewed as external to ecosystem function” – an idea suggested by Harvey and used by the authors to reinforce the interconnections of physical and social fabrics in urban spaces. Moving to “uneven geographical development” the authors discuss the matter of justice, explaining the differences and complementarities between Urban Political Ecology (which they define in this paper, as a scholarly framework derived from political economy and ecology – more focused on distribution and with a multi-scale perspective) and Environmental Justice (a perspective that came from social movements into academia – more focused on local issues and other forms of oppression beyond economic, such as gender, race, ethnicity). This article contributes to my project as it explains the process of city-making as one that is not only defined by human-nature relations but also a consequence of social inequalities within human groups.

Tassinari, Wagner De Souza, Débora Da Cruz Payão Pellegrini, Paulo Chagastelles Sabroza, and Marilia Sá Carvalho. “Distribuição Espacial Da Leptospirose No Município do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, ao Longo dos Anos de 1996-1999.” Cadernos de Saúde Pública 20, no. 6 (December 2004): 1721–29. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2004000600031.

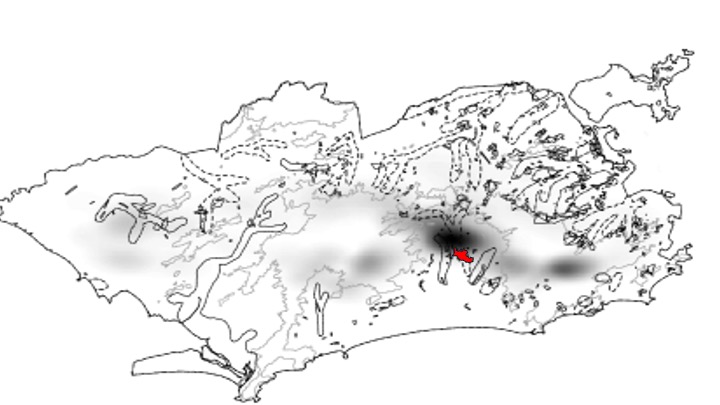

This article consists of an epidemic study based on geographic information systems to understand the gravity and causes of the leptospirosis epidemic that afflicted the city of Rio de Janeiro between 1996 and 1999. The maps created by this study demonstrate that the epidemic was initially spread all over the city, due to the flood of 1996, but during the last two years it became concentrated in favela areas in between the neighborhoods of Vargem Grande and Jacarepagua (close to the area where Cidade de Deus is located). The study also tries to understand the causes for this pattern and considers that the permanence of leptospirosis in the area is due to its high social-environmental vulnerability. This contributes to my project, as it demonstrates how the people from this neighborhood kept suffering the impacts of the 1996 flood, years after it happened.

Image Analysis:

Two Rios in carnival 1996: “eternal grief” and “a bombardment of happiness”

This image analysis essay focuses on Rio’s official samba school carnival parade in 1996, which took place from February 16 to February 20 at the Sambadrome Marquês do Sapucaí. This report presents a brief contextualization of this event, followed by an analysis tracing the relationship of the carnival parade of 1996 with the flood disaster of that year. The two contrasting images analyzed here portray the tragedy and the indifference that surrounded that moment, as an analogy to the realities of different segments of the population, who live in different “Rios”. The first image is called “eternal grief” in allusion to the protest banner of samba school Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá, from the neighborhood Cidade de Deus. The second image demonstrates how some segments of Brazilian society were indifferent to the tragedy, including media portrayals of the carnival parade in its usual “greatest happiness,” or, as we see in the headline by Manchete magazine: “a bombardment of happiness.”[1]

Contextualization

The world-famous spectacle of Rio de Janeiro’s carnival is a multiple-day event held every year during the holiday, which tends to happen in February or early March. It takes place at the “sambadrome,” also known as “the samba runway,” a purpose-built stadium inaugurated in 1984 specifically to host the annual parade of samba schools. The stadium, shaped as a 2,300 ft alleyway, was developed with structures on both sides, to accommodate an audience of 70,000 people[2]. During the carnival festival every year, each samba school organizes a parade to be presented at the Sambadrome. The carnival parades work as a competition among samba schools, which are organized into a league: the “Special Group” (first division), Group A (second division, or “the Access Group”), Group B (third division), and so forth. Their performance is evaluated by an expert jury which grades a series of categories, defining the winner of carnival, as well as samba school positions in the league for the following year: who gets promoted or relegated. Samba schools in top divisions parade at the Sambadrome Marquês do Sapucaí, while schools in lower divisions parade in different locations of the city. The parades of the Special Group have been broadcasted in real time to a national audience by Globo TV, which detains the television rights to broadcast the event since 1965.

A large samba-school has around 3,000 performers participating in their parade, while smaller samba schools would have around 2,000. Although they are called “schools,” they are not organizations aimed at education or instruction. Each samba school operates more as a social club and is associated with a different community. They are traditionally from poorer neighborhoods, where the majority of the population is Afro-Brazilian. Every year, each samba school organizes their parade around a theme of their choice, which will be described in the “samba-plot,” a song composed specifically for that occasion, to be sung throughout the parade presentation while each section of the samba school passes through the Sambadrome in their colorful costumes. Usually, themes reflect on social inequalities, human creativity and inventiveness, or pay homage to people or peoples. Samba schools are deeply connected with a history of African cultural heritage preservation throughout time, and Afro-Brazilian resistance in spite (or in defiance) of injustice and authoritarianism.

The samba school carnival festival has been an important part of Rio de Janeiro’s (and Brazil’s) culture. For the city’s elite, however, the advantages of holding this yearly event go far beyond promoting leisure and cultural heritage. Rio’s carnival is an important source of revenue for the urban economy, as well as an important driver of tourism. For example, the municipality of Rio estimated that carnival 2025 would generate around USD 1 billion for the city’s economy.[3] Several industries profit from carnival. Media conglomerates, for example, count on the samba school competition as one important annual event, that generates significant advertising revenue, as this is broadcasted in real time to a national audience – the Brazilian equivalent of events such as the “Superbowl” in the U.S. The business side of carnival is possibly one of the reasons why the festival has become so important for the local elite. The City Hall provides funding for samba schools to prepare their parades, which can even generate temporary work opportunities for seamstresses, carpenters, welders, and other laborers among the samba school members.[4] Top-tier samba schools (such as the ones in the special group/first division) receive more funding and more opportunities.

In 1996, the spectacle took place from February 16 to 20 (3 to 7 days after the flood). In spite of the disastrous tragedy that happened in the same week of the carnival, the celebrations just went on – while the work to rescue victims and to count deaths was still ongoing in the city and in the state.

For this historical analysis, the report follows the news about samba schools that paraded in 1996. The main samba school presented by this essay was in the third division and therefore had to parade on February 16 (only 3 days after the flood): Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá (located at Cidade de Deus and representing the neighborhood in the carnival competition). The other samba schools mentioned in this essay were in the special group and paraded on February 18 and 19 (5-6 days after the flood): Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel (which received great media attention, as it was the winner of that year’s carnival) and Imperio Serrano (which had chosen to pay a homage to Betinho and his solidarity campaigns as their theme in 1996).

The Rio of tragedy: “eternal grief”

Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá, the samba school from Cidade de Deus, could not present their full parade that year. Instead, they made a symbolic parade of grief and protest. At that point, only three days after the beginning of the disaster, the final number of deaths in Cidade de Deus was still unknown, but the confirmed casualties were already counted by dozens. The majority of the performers was not able or not willing to participate in the samba school parade. Many of them had lost family and friends, and almost all of them were facing material losses. Their neighborhood had been the one most affected by the flood, and was significantly damaged. A school member told Jornal do Brasil “everybody is traumatized.”[5]

The samba school, therefore, did not make their full presentation. Instead, they made a quasi-silent protest with a single bass drum playing while members walked the avenue crying. According to O Globo, no more than 100 out of the 2,000 members participated in the symbolic parade[6]. According to Jornal do Brasil, the group was just over 50 members, and the presentation lasted only about 20 minutes.[7] Manchete magazine, a social life news outlet, defined it as a “parade of bitterness” and explained that the samba school “lost significant part of its costumes, destroyed by the waters, and worse, 23 of its members – among them several children – dead in consequence of the flood. (…) The few members who could attend the presentation shared their pain and tears with the audience, who, in solidarity, clapped and also cried.”[8]

One of the samba school musicians from Cidade de Deus told Jornal do Brasil that their community was facing more than 200 deaths and was corrected by the newspaper: “it is estimated that the number of deaths may reach 200, but in the state as a whole.” The musician said he was confident the jury commission would understand that it was not possible to parade in those conditions, and therefore not relegate the school’s position in the league. The president of the Samba Schools Association, however, was less certain about that. Gustavo Diamante said “the regulation does not have a position about a situation like this.” According to Jornal do Brasil, the samba school Império da Tijuca had also presented a symbolic parade in 1966, due to the flood of that year, and was not punished for this.[9] The report from O Globo newspaper, however, was more discouraging, quoting these words by Diamante: “according to the regulation, the school would be automatically relegated, as it did not parade. (…) The situation will have to be analyzed as a separate case. We will have a meeting to discuss this issue.” The newspaper O Globo complemented that the attitude by the samba school directors (of protesting instead of parading) could lead to relegation. “As the school passed by Sapucaí with insufficient performers, no floats, no samba-plot, and practically no costumes – the club will not earn points for any of these categories” sentenced the newspaper, which belongs to the same media conglomerate as Globo TV, the long-time possessor of the rights for the live transmission of Rio’s carnival to a national audience.

“I think we should have the right not to parade” said one of the school’s members, who had lost two friends to the flood. The samba school president explained: “We wouldn’t be able to parade. We are here just to comply with the regulation.” The samba school’s drum corps master said “we are here to pay respect to the audience, who has been very solidary. Cidade de Deus is still shocked by what happened. Our carnival was over before it started.” The solidarity also came from another samba school, Independentes de Cordovil, which dedicated a minute of silence for the victims from Cidade de Deus as they prepared to enter the Sambadrome for their parade. The school’s president affirmed: “the authorities have to look to these needy people with more kindness.”[10]

Both O Globo newspaper and Manchete magazine displayed photographs of children in regular clothes, holding hands and crying while walking the samba runway during the symbolic protest-parade. Jornal do Brasil, like Globo TV, showed the banners the samba school had arranged for their presentation. The first banner said:

“Our quilombo is in mourning for the flood that hit Cidade de Deus. We lost members in the storm, but we have not lost respect for the people.”

Presentation from Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá on February 16, 1996. The banner reads “We are still counting the victims of the storm. Our ‘quilombo’. Eternal grief.” Image: screenshot of the documentary film “Enchente” (with video footage ceded by Globo TV).

The first image analyzed in this essay is a screenshot of Globo TV’s transmission, showing one of the banners, which reads:

“We are still counting the victims of the storm. Our ‘quilombo’. Eternal grief. GRES Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá.”

“Quilombo” is a word associated with autonomous ancestral communities of African origin formed during and after the slavery period in Brazil (maroon societies). The most famous quilombo in the history of Brazil was Quilombo dos Palmares, a community made of Afro-Brazilian people who had escaped slavery. This settlement lasted from 1605 to 1694, and hosted a population of thousands of inhabitants, with estimates ranging from 11,000 to 20,000. Palmares had its own government, with a form of political organization inspired by several Central African models. In 1996, the samba school from Cidade de Deus (Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá) was going to present a parade based on the theme “Quilombo dos Palmares, a black paradise,” had the flood not happened three days before carnival.

Today, there are many quilombo communities in Brazil. The term is associated with territories of Afro-Brazilian resistance and autonomy, where black culture is preserved, and abolitionist practices are upheld. According to contemporary scholars, such as Guimarães[11] and Vaz,[12] Cidade de Deus can be understood not only as a predominantly black population, but as a black territory – where social-political relations are defined by a recognition of ancestral connections with Africa. From this perspective, it is possible to understand the word “quilombo” on the banner not only as a reference to the samba school’s theme for that year, but as a sign of abolitionist resistance, denouncing the structural racism in Brazilian society. On the first banner in their parade, the words “our quilombo is mourning” mean that the community identifies as a quilombo, a territory of black resistance. “We have lost members to the storm but we have not lost the respect for people” possibly refers to the lack of respect and indifference given by the authorities to the people from Cidade de Deus.

In the report by O Globo, the newspaper mentions “the school from Cidade de Deus dressed grief for the people who died in consequence of the rains.” The image, however shows people dressed in white, instead of the usual black color used for funerals in European/Western traditions. The reason for this is the meaning of white clothing in Afro-Brazilian religions, such as Candomblé. In these traditions, funeral ceremonies usually have participants dressed in white, a color that symbolizes life and death, beginning and end. The words “our quilombo is mourning” and the Candomblé clothing to symbolize grief clearly signal a perspective based on Afro-Brazilian resistance during the protest. “Eternal grief” certainly refers to the grief caused by the flood tragedy, but it may as well refer to the grief caused historically by violence against black people.

The Rio of indifference: “a bombardment of happiness”

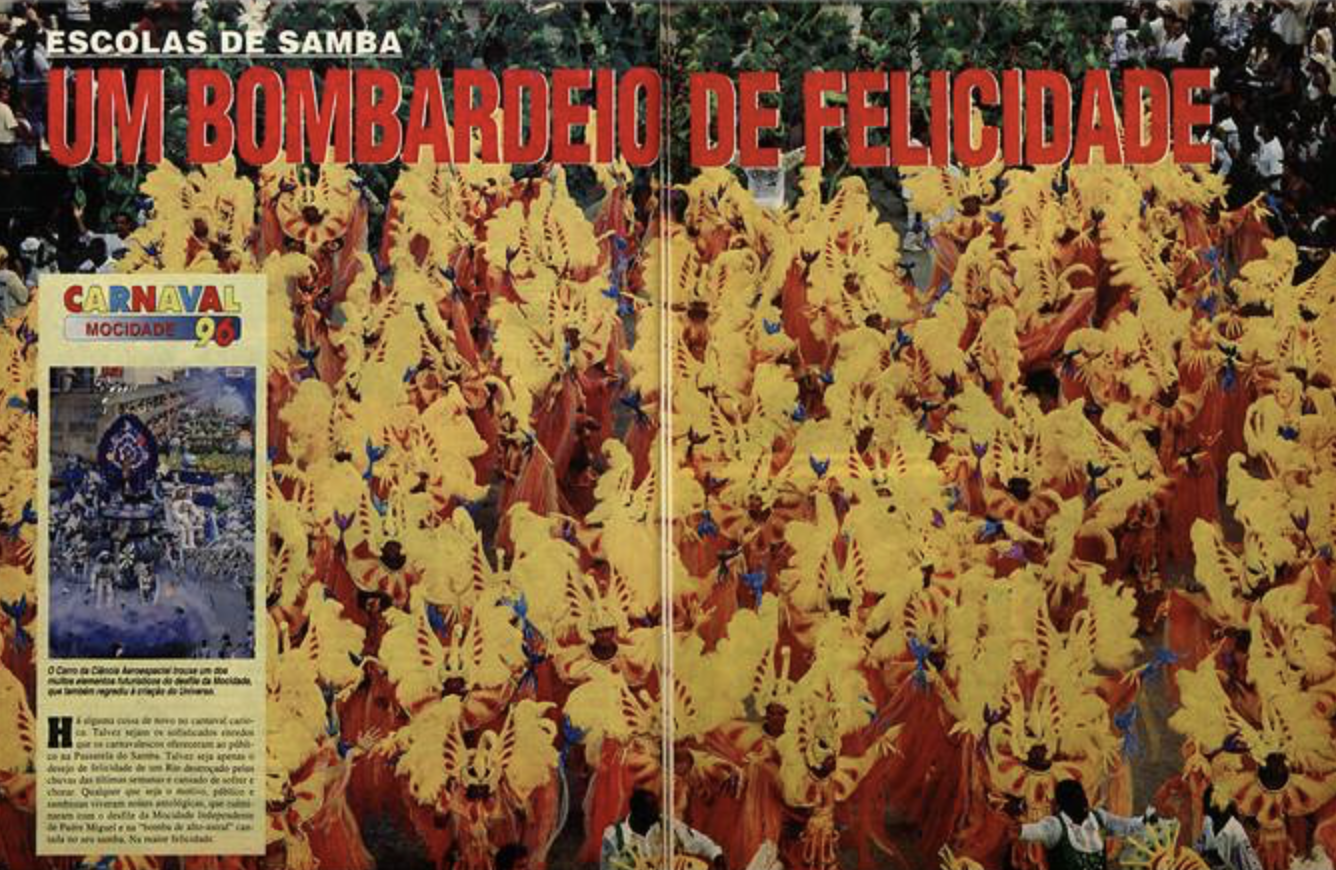

The second image analyzed by this essay is from Manchete, a weekly magazine from Rio de Janeiro that centered on social life and local celebrities. This report focused exclusively on the issue of February 24, 1996, which was published 11 days after the flood and 8 days after the presentation from Mocidade Unida de Jacarepaguá, depicted above.

The image is a two-page introduction to the carnival coverage, which was the topic for the entire issue – featuring all samba schools in the Special Group in Rio, as well as carnival festivals, balls, and parties held in Rio de Janeiro and a few other cities. It depicts a picture of carnival winner Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel’s parade with the headline: “Samba schools / A bombardment of happiness.” Below, a box with an additional picture of the same parade and an introductory text about the carnival of 1996.

Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel is the winner of carnival 1996 with the samba-plot “Creator and Creature,” which celebrates human inventiveness (but warning that it can be used for good or evil, for peace or for war) with the lyrics:

A mão que faz a bomba, faz o samba / The hand that makes the bomb, makes the samba

Deus faz gente bamba / God makes “bamba” people (people who dance)

A bomba que explode nesse carnaval / The bomb that explodes in this carnival

É a Mocidade levantando o seu astral / Is Mocidade lifiting your spirits

Inspired by these lyrics, Manchete magazine created the headline “A bombardment of happiness” to open the coverage of carnival 1996 in the magazine. That would be a regular way of reporting carnival, however, a disaster had happened in that same city and state days before, with an estimate death count of 200 people. The magazine could not publish the carnival coverage without acknowledging it. The solution was to write an introductory text (on the box, below the small picture) explaining the awkward celebration amidst the tragedy:

“There is something new about Rio’s carnival. Maybe it’s the sophisticated themes that the carnival artists offer the public on the Samba Runway. Maybe it’s just the desire for happiness from a Rio de Janeiro devastated by the rains of the last few weeks and tired of suffering and crying. Whatever the reason, the public and the samba dancers enjoyed anthological nights, which culminated in the parade of the Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel and the ‘high-spirited bomb’ sung by their samba. In the greatest happiness.”

Headline “A bombardment of happiness” on Manchete magazine from February 24, 1996 (11 days after the flood). The picture shows the colorful samba school presentation by that year’s carnival competition winner, Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel. The presentation shown in the picture had happened on February 18 (5 days after the flood). Image: Manchete magazine, February 24, 1996 (source: Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira).

END NOTES

[1] Manchete magazine, February 24, 1996. p. 5-6.

[2] The Sambadrome is a “purpose-built stadium constructed specially to host the annual parade of Samba Schools each year during the festival of Carnaval in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. (…) The Rio de Janeiro Sambadrome is comprised of free-standing individual structures for spectator viewing, called sectors, which sit on both sides of a long alleyway down which the Samba Schools parade.”

Source: Sambadrome.com. “About Sambódromo.” Access: May 10, 2025. https://www.sambadrome.com/rio-carnival-sambodromo/

[3] Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro, February 27, 2025. https://en.prefeitura.rio/desenvolvimento-economico/carnaval-2025-vai-movimentar-r-57-bilhoes-na-economia-da-cidade-segundo-estimativa-da-prefeitura/

[4] The Associated Press, March 2, 2025. https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/a-samba-school-rises-to-rio-carnivals-top-league-bringing-an-economic-boom-to-its-poor-residents/

[5] Jornal do Brasil, February 18, 1996, p. 24

[6] O Globo, February 18, 1996, p. 13

[7] Jornal do Brasil, February 18, 1996, p. 24

[8] Manchete, February 24, 1996, p. 42

[9] Jornal do Brasil, February 18, 1996, p. 24

[10] O Globo, February 18, 1996, p. 13

[11] Guimarães, A. F. da S. (2024). TERRITÓRIOS E TERRITORIALIDADES NEGRAS NA CIDADE DE DEUS [Thesis, Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso do curso de Especialização Planejamento e Uso do Solo Urbano]. https://pantheon.ufrj.br/handle/11422/24702

[12] Vaz, P. (2018). FAVELA CITY OF GOD(DESSES): FROM A PLACE OF NECESSITY TO A SPACE OF POLITICS [Dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/m900nt659