Agent Orange: Environmental Injustice at Home and Abroad

by Susan Cohen

Site Description:

As a historian interested in American foreign affairs and legal history, researching the use of Agent Orange is an interesting and relevant way to connect foreign policy and law. With environmental injustice such a large issue today, understanding past injustices is essential in combating injustice today.

Between 1961 and 1971, the United States sprayed more than 20 million gallons of various herbicides over Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Agent Orange, a powerful herbicide, was used to eliminate forest cover and crops for the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops. Agent Orange, which contains the deadly chemical dioxin, was later proven to cause serious health issues among both the Vietnamese and returning US servicemen and women.

While Agent Orange was sprayed over Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, there is another site relevant to the story of Agent Orange: the Diamond Alkali plant used to create Agent Orange located in Newark, New Jersey. Dioxin was dumped into the Passaic River resulting in the pollution of the Ironbound area for years.

In considering that Agent Orange polluted both areas in the United States and in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, a number of questions arise. First, how did the United States respond to the pollution crisis in the United States versus how they responded to it Vietnam? Second, in specifically looking at Newark, how much of a role did race or class play in the response of the United States government? In conjunction with that question, how much did race or class play a role in the United States deciding to spray Agent Orange in Vietnam? How was the use of Agent Orange justified by the United States, and how did the United States deal with the eventual fall out? As there is a chemical site both in the United States and Vietnam that deal with the same chemical in the same time period, this will make for a very good way to compare the United States’ approach to environmental problems both at home and abroad.

While the use of Agent Orange took place in the 1960s and 1970s, the controversey of it is far from over. While President Bush signed the Agent Orange Act, which mandated diseases caused by Agent Orange be treated a result of wartime service, US courts rejected a suit initiated by the Vietamese people affected by Agent Orange in 2005. As late as 2011, navy men who served in Vietnam were petitioning to be included under the Agent Orange Act and people in Vietnam still suffer from disease and birth defects linked to Agent Orange. The history of Agent Orange, and the varying levels of environmental injustice that connect with race and class, provide a better understanding of just how big a role race and class play when it comes to environmental injustice.

The topic of Agent Orange, and the effects it had in the United States and Vietnam allows for a comparison to be made between how the environment is treated by the United States both at home and abroad. The fact that there are two sites to research allows for an in depth look at how race and class play a role in environmental injustice. Looking at the creation and use of Agent Orange raises a number of questions. How did the United States respond to the pollution crisis in Vietnam versus how they responded to it in the United States? What role did race and class play in choosing where to spray Agent Orange and where to create it? How did the United States respond to the crisis of Agent Orange at home versus how they responded to the problem in Vietnam? As the effects of Agent Orange are still affecting people in the United States and Vietnam, the topic of Agent Orange remains extremely relevant. Both American and Vietnamese people are still fighting the toxic effects of Agent Orange and to do so are attempting to hold the United States and the chemical companies involved accountable for their actions.

Final Report:

In the 1990s, 72 people sued for medical problems related to Agent Orange exposure, including skin diseases, cancer, hormonal diseases, diabetes, and infertility. For years, these people lived with continuous exposure to Agent Orange as it infested the water and soil around them. While Agent Orange was used in the 1960s and 1970s, it took years for people to realize that the hardships they were experiencing were a result of Agent Orange. Families faced devastating losses, cancer rates increased and children were born with debilitating disabilities. Water sources were declared toxic, dioxin levels in soil remained high and no one seemed inclined to help the people or the environment. In the 1980s, reporters uncovered and reported on the devastating effects of Agent Orange bringing attention to an issue that most had stopped discussing. In their stories, reporters exposed the dangers of Agent Orange, detailed the medical effects that Agent Orange can have on people and discussed the lack of attention the issue was receiving. Pictures were used to show the water sources poisoned by Agent Orange, maps were used to show the areas affected, and pictures of people were used to show the physical effects Agent Orange can have on the human body. All of this data was used in the lawsuit brought by 72 people in the 1990s.

By the 1990s, the toxic effects of Agent Orange were no longer a huge surprise: the fact that not one of the plaintiffs involved in the lawsuit had even been in Vietnam was a surprise. In fact, all 72 of the people who sued Diamond Shamrock Co, the company that had produced Agent Orange during the Vietnam War, were exposed to Agent Orange in the Ironbound section of Newark, NJ.1

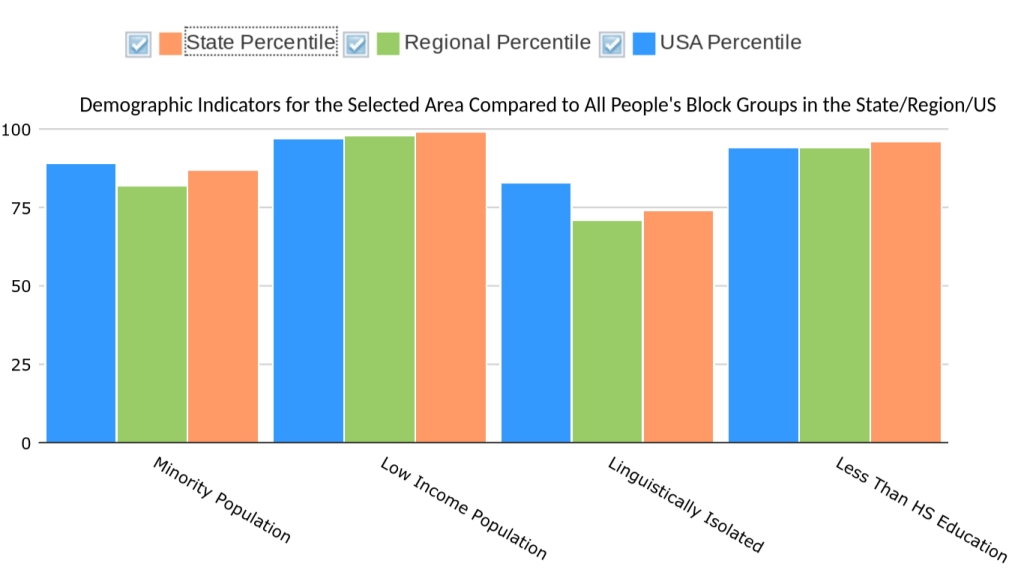

The Ironbound section of Newark, New Jersey consists of a majority-minority, low-income population which can be used to help explain how such devastating injustice could take place. The Ironbound is home to African American and Mexican American communities most of whom live at or below the poverty line. Many of the people living there have not completed high school education and speak English as a second language.2 The racial makeup of the Ironbound and the socioeconomic status of the people directly correlate to the environmental injustice that took place throughout the 1960s and 1970s. By 1990, activist groups had been pushing the United States government to consider the role of race and class when it came to environmental injustice. In 1992, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was tasked with creating a report that analyzed the correlation between the location of hazardous waste facilities in communities and the number of minority people located in those communities. Their findings corroborated the theory that race and class play a significant role in environmental injustice.

At the same time that residents of Newark were fighting to gain compensation for their exposure to Agent Orange, the people of Vietnam and the United States veterans who served in Vietnam were also fighting for compensation for their exposure to Agent Orange. United States veterans came together to lobby congress for compensation, were successful in gaining it and continue to receive benefits that help treat diseases linked to Agent Orange exposure. On the other hand, Vietnamese civilians have tried numerous times to gain compensation, both when it comes to their health and the environment, but have been largely unsuccessful. As the EPA documented in 1992, the role of race and class is extremely important in understanding who is exposed to toxic sites and who is not. Taking that one step further, it is also important to consider race and class when it comes to who receives compensation for environmental injustice and who does not.

While many know about the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam, a majority of people have not made the connection between the environmental injustice that took place in Newark at the same time. For years, residents of Newark and civilians of Vietnam have used grassroots

movements and legal action to try and get chemical companies to compensate them for the damages done to them due to the production and use of Agent Orange. Both residents of Newark and residents of Vietnam have created organizations to provide assistance to those affected by Agent Orange. In addition, both people in Newark and Vietnam have used legal means to try and gain compensation. They have done this by suing the chemical companies responsible for the creation of Agent Orange as chemical companies knew the dangers of Agent Orange and sold it to the government anyway.

The creation and use of Agent Orange, the effects of Agent Orange and the fight against chemical companies creates a transnational history between the people of Newark and the people of Vietnam. To highlight the transnational history shared by residents of Newark and Vietnam, it is important to consider how the veterans have been treated when it comes to the issue of Agent Orange exposure. The veterans have been successful: the people of Newark, although also United States citizens, continue to fight for compensation and help just like the people of Vietnam. The continued fights on the side of Newark and Vietnam, in contrast to the success of the veterans, shows that there is still more to do in addressing those affected by Agent Orange.

In regards to scholarship on the use of Agent Orange and the effects it has had on United States veterans, historians have discussed military history, legal history and social history. Historians have discussed the effects Agent Orange had on the US army, veterans and the way that Agent Orange affected the job US soldiers performed in Vietnam. Historians have also traced the legal history of the fight veterans undertook to gain compensation for their exposure to Agent Orange. They have discussed how veterans had to come together, use a variety of legal methods, and use a variety of grassroots movements in order to see success in their fight for justice. Historians, as well as the Veterans Affairs Bureau have continued to monitor the effects Agent Orange has on veterans and documentation on those affects encompasses a large amount of material. 4

In contrast to the large number of sources that discuss Agent Orange in regards to US veterans, there is a shockingly small amount of material that discusses the effects of Agent Orange had on people in Newark and people in Vietnam. Published scholarship on Agent Orange in Newark consists of several short papers that discuss the story of what happened and how dioxin affects the Passaic River. In regards to the effect of Agent Orange on the people of Vietnam, there is one dissertation and a couple of articles.5 While scholarship is sparse, there are numerous newspaper articles, legal documents and interviews that address both the residents of Newark and the civilians of Vietnam.

The lack of scholarship on Agent Orange in Newark and Vietnam helps to explain why there is no mention of the transnational history that exists between the two places. The lack of scholarship leaves huge gaps in our understanding of Agent Orange and the effects it has had on people. This gap in scholarship opens the door to a series of questions about those affected by Agent Orange, the role race and class plays in environmental injustice, and ultimately, what can be done to help those still suffering. The first questions that needs to be asked is how can Agent Orange be used to show the transnational history that exists between Newark and Vietnam? Second, what role did race and class played in the decision to produce Agent Orange in Newark and spray it over Vietnam? Third, how can the success of veterans be used as a juxtaposition to understand the importance of race in class when it comes to success in fighting environmental injustice? And last, how have people in Newark and Vietnam fought for rights and against injustice? All of these questions serve to bring to light the transnational history that exists between Newark and Vietnam in regards to Agent Orange.

As scholarship on the subject of Agent Orange in Newark and Vietnam is sparse, a multitude of primary sources will be used to explore new avenues of how Newark and Vietnam share a history. Newspaper articles, congressional documents, photographs, lawsuits and statistical data will be used to showcase how the people of Vietnam and Newark suffered from the same injustice. In addition, secondary sources including books and journal articles will be used to help provide an understanding of just how devastating Agent Orange has been, and continues to be, on both the people exposed to it and the environment.

Aspects of transnational history, legal history, environmental history, and social history will be woven together to provide an in depth understanding of the complexities that make up the history shared by Newark residents and Vietnamese civilians. The transnational history will help develop the idea that groups of people an ocean away were affected, and continue to be affected by the same problems. The shared story between the people of Vietnam and Newark goes beyond the fact that they were both exposed to Agent Orange: communities and the environment in both places continue to suffer from the effects of Agent Orange. Because of this, aspects of social history and environmental history will be woven together to build up the transnational history that exists, while at the same time documenting the different experiences people in Newark and people in Vietnam continue to face. Last, an examination of legal history will be used to show how people in both Newark and Vietnam have attempted to gain compensation for the injustices they faced.

Using a variety of methodological approaches, this paper will explore the ways in which the people in Newark and the civilians of Vietnam share a history. The analysis of sources will showcase that both those in Newark and Vietnam were victims of environmental injustice through the use of the same chemical: Agent Orange. Additionally, in exploring how those in Newark and those in Vietnam sought compensation, the transnational history continues to develop. The legal cases brought by Vietnam and Newark, although separate, are ongoing. Exploring these cases will show that although Vietnam and Newark brought independent lawsuits, at different times, there is an overlap between the two cases when it comes to precedent and subsequent appeals cases. Comparing experiences of US veterans in their fight for compensation to the experiences shared by those in Newark and Vietnam will show that in many ways, the underprivileged of Newark and the civilians in Vietnam share more of a history in this instance than Americans share with United States servicemen and women.

Between 1961 and 1971, the United States sprayed millions of gallons of Agent Orange in Vietnam; this fact has been the object of study for dozens of books and articles written by historians. In researching Agent Orange, scholars have concluded that the chemical has had devastating health effects on both the people of Vietnam and US servicemen. Many have done in depth studies to analyze the impacts of Agent Orange on the environment, people and communities exposed to Agent Orange. 6 Still contested, is what Agent Orange can cause, how many continue to be affected by exposure to it, and how the United States government should deal with the problem.

For many scholars and veterans, there is a misconception that the United States government willingly used Agent Orange knowing of its devastating health effects. In fact, when the United States government began to use Agent Orange in 1961, they were under the impression that Agent Orange was safe for both people and the environment. As reported in the New York Times in 1983 “When Dow in 1970 warned the Defense Department about the dangers of Agent Orange, military officials declared that they were hearing about the problem for the first time.”7 Not only did the government not know about the dangers of Agent Orange, “Dow and 7 other chemical companies shielded from the government from information that one of the herbicides, Agent Orange, contained dangerous levels of dioxin.” 8 Despite the fact that the US stopped using Agent Orange once it became aware of the dangers, the US has refused to accept any liability for their use of Agent Orange and instead insists that its use had saved the lives of Americans and its allies.9

In recent years, rigorous studies conducted to measure the levels of dioxin still present in the blood samples of children in both North and South Vietnam show that the disadvantageous Vietnamese continue to suffer the most from Agent Orange.10 These studies indicate that Vietnamese citizens suffer from far greater exposure than any other group of people- including United States veterans.11 In addition to the health effects Agent Orange continues to have in Vietnam, the toxin is also present in Vietnamese refugee communities. The spraying of Agent Orange forced over two million refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to other countries including the United States and European countries.12 Despite the fact that these people left Vietnam, it has been reported that they continue to suffer from pain in the eyes and skin. In addition, there has been multiple studies done to prove the link between Agent Orange exposure and birth defects.13

In Vietnam, the people most affected by Agent Orange are the poor. Dozens of orphanages house thousands of children all born with birth defects- many claim a result of Agent Orange. Today, those who live in flooded areas, fish-farmers and those who are older are more likely to have high levels of dioxin in their blood.14 Photojournalist Damir Sagoli writes about a family he met while in Vietnam: “Back in Danang, next to its international airport, we visited a young couple who have lived and worked there since late 1990s. When they first moved there the man used to go fishing, collecting snails and vegetables to bring home to eat. The family was poor and all food was welcomed…His daughter was born sick in 2000 and died aged seven. Their son was born in 2008, also sick with the same symptoms as his late sister.15

The chemical makeup of Agent Orange means that it can continue to affect disadvantageous groups in Vietnam for dozens of more years. Agent Orange is made up of dioxin- a chemical that can stick around for decades. In Vietnam, when the US sprayed Agent Orange, it was absorbed by trees, leaves, and soil. From there, dioxin moved in surface runoff and clung to sediment particles in wetlands, marshes, rivers, lakes and ponds. The dioxin was then ingested by bottom feeding fish like shrimp. The dioxin then binded with the fatty tissue in these animals- when other fish ate these animals, they ingested the dioxin. This cycle continued up the food chain and affected many Vietnamese who rely on fish as the basis of their diet. While the Vietnamese government has tried to ban fishing from contaminated sites, those who are poor need to continue fishing in these areas helping to explain why the poor people of Vietnam continued to be so heavily impacted by Agent Orange.16

As Agent Orange continued to affect civilians living in Vietnam, both the people and government of Vietnam have tried to get the US to fix the chemical damage done to the Vietnamese environment. For many years, the issue of Agent Orange was pushed to the sidelines as more important issues were resolved. Now, however, the issue is a regular topic of conversation in bilateral discussions. In the last few years, the people of Vietnam have become increasingly concerned about the issue of Agent Orange. Various non-government organizations are placing pressure on the Vietnamese government to remove dioxin from the environment and to provide better care for the people exposed to Agent Orange. To help, the Vietnamese government has sought US assistance. But, while the US has provided scientific and technical support, it refuses to acknowledge any legal liability to provide assistance. 17 As a result, Vietnamese organizations would gather together to sue the chemical companies who produced and sold Agent Orange during the war.

In addition to a disregard for Vietnamese civilians and the Vietnamese environment, the creation and use of Agent Orange irreparably damaged both the environment in Newark and the health of its most disadvantageous groups: minority, low-income communities. The Diamond Alkali factory in the Ironbound of Newark was placed in an area home to minority groups who have low incomes and who are not English speaking. People in these areas continue to suffer from the effects of Agent Orange which has had momentous impact on the health and well-being of the people in this area. As in Vietnam, the people in Newark affected by Agent Orange are some of the poorest in the country. 70 percent of the families are classified as living below the poverty line and 22 percent of the families have three or more victims who suffer from the effects of Agent Orange. Many are very seriously disabled; 90 percent are jobless. The burden of care for these victims falls on parents or relatives, many of whom are now in their old age.18

As early as the 1940s, the production of DDT and other chemical products began at 80 Lister Avenue in Newark, New Jersey. The Diamond Alkali company, which owned chemical factories, first produced Agent Orange in the 1950s. Agent Orange is made up of two herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, neither of which are toxic on their own. However, when Agent Orange was produced, a toxic byproduct, dioxin TCCC, formed. 19 Continuing into the late 1950s and 1960s, the Diamond Alkali Company continued to produced Agent Orange despite concerns many had over the effects of the chemical.

While factory workers who produced Agent Orange suffered from numerous health effects, their need for work meant they tolerated the side effects that came with the job. Between 1951 and 1969, Diamond Alkali Co received numerous memos from C.H. Boehringer Son, a West German chemical company that warned of the dangers associated with the byproduct of certain herbicides. In an interview, Dr. Roger Brodkin, head of dermatology at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey recalls that factory workers were often plagued by “painful and disfiguring skin diseases.” Brodkin further explained that though they didn’t know it at the time, factory workers would also suffer from liver damage and became more prone to certain types of cancer.20 Brodkin explained that, “it was rough (for workers), but the money was good and they tolerated it.” 21 From someone who saw the conditions of the factory up close, his observation that the workers tolerated such horrific conditions because of the pay indicates that money was a core reason why people continued to work in such horrible a place.

The way that Agent Orange was produced demonstrates a complete lack of caution for the health and safety of the factory workers. Several former factory workers have made statements about the state of the factory and the production of Agent Orange. Harry Heist was employed at Diamond Alkali from 1966 to 1969. “There were spills all the time,” Heist told The Newark Star-Ledger in June 1983. “The reactors would run away, boil over and stuff would flow down the sides of the tanks and troughs on the floor that led to the river. The stuff was all over the place.” To get rid of the excess Agent Orange, workers were tasked with dumping it all into the Passaic River. 22 During the 1960s, Dr. Roger Brodkin treated up to 50 employees of the 22 factory for ailments related to dioxin exposure. Brodkin, in a 1983 interview, explained that he made weekly trips to the plant to treat workers. He explained that the reason he went there is that “there were so many of them affected that if they were to send them out to us, they’d have to close down a shift…instead, they were willing to pay us to come there.”23

The production of Agent Orange in Newark had several long term effects on the city of Newark in regards to both population and the environment. In 1971, Diamond Alkali sold 80 Lister Avenue, and by 1983, the state of New Jersey and the EPA found that 80 Lister Avenue and surrounding areas tested positive for high levels of dioxin. With the results of the test, Governor Thomas Kean urged residents within 300 yards of the plant to voluntarily relocate as a precaution; many residents explained that they had nowhere else to go and had to remain in their homes. 24 “It was like an invasion,” recalls Nancy Zak, a longtime neighborhood resident, who 24 works for the Ironbound Community Corporation, a local nonprofit. “All these guys in these moon suits were walking around. We’re wearing our regular clothes. Nobody’s telling us we should dress or do anything differently. It was a shocking day for people.” 25 Testing continued in the Ironbound and samples were taken from vacuum cleaners, vacant lots, business ventilation systems and more. As a result of the tests, in 1984, the site was listed on the Superfund National Priorities List demonstrating just how problematic dioxin levels in the Ironbound were. 26

Despite the fact that factory workers had been treated for dioxin related diseases since the 1960s, the poor, minority status of the area, meant that it took until 1983 for reporters to start asking questions about dioxin in Newark. Reporters became concerned with the environmental impact the shut down Diamond Alkali factory was having on Newark. In 1983, the Diamond Alkali site contained 66,000 cubic yards of dioxin contaminated soil, the remains of the factory building and debris. 27 In addition to the soil and debris found in the factory site, the water in the surrounding area, namely the Passaic River, was also highly affected by the production of Agent Orange. In his testimony against Diamond Alkali, plant worker Chester Myko called the floor of the former plant “the dirtiest place on the entire planet.” He continued to explain that “workers hosed down the floor with sulfuric acid every week or so, directing wastewater into open trenches and then into the Passaic. In agreement, Aldo Andreini, who cleaned the tanks used to store Agent Orange ingredients explained, “once or twice a month I would shovel sediment from the storage tanks into metal drums. The liquid and solid waste got spilled onto the ground would be washed away into the Passaic.” This, in addition to the company policy of simply dumping Agent Orange into the Passaic River made the water extremely problematic.28

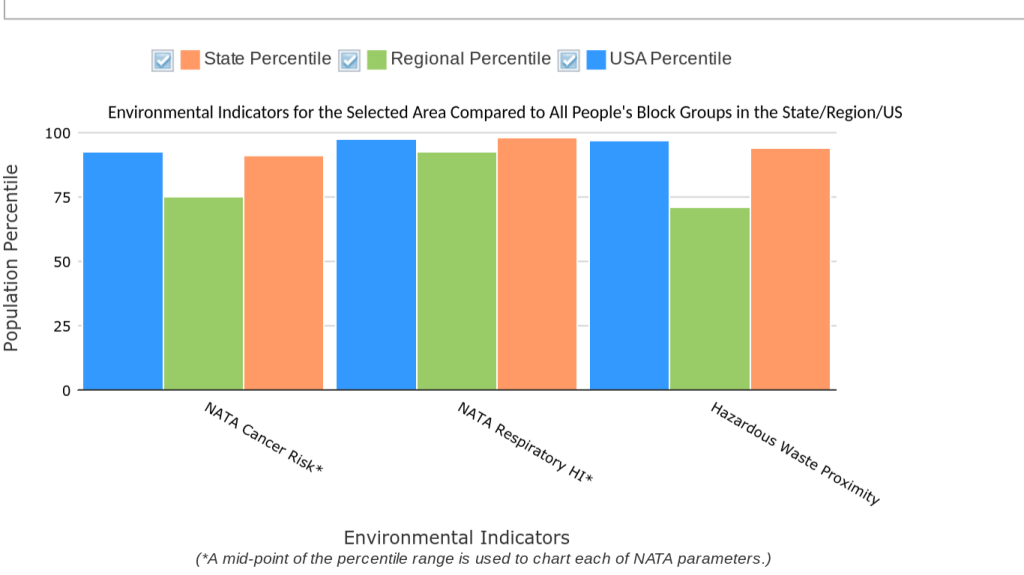

While both the water and soil surrounding the Passaic have been affected by Agent Orange, the area also leaves residents with an increased chance of developing cancer or respiratory problems. According to the EPA, NATA respiratory hazard index can be defined as the calculation of each hazard index’s “ratio of the exposure concentration in the air to the health-based reference concentration set by the EPA,” in other words, inhaled air that has more toxins in it than allowed by the EPA. Statistically, the Ironbound is in the 92nd percentile state wise, 88th percentile region-wise and in the 94th percentile in comparison to the rest of the United States.29 Toxins in the air are inhaled and can therefore lead to respiratory problems. 29 When it comes to the NATA cancer risk, the environmental site is in the 91st state percentile, 70-80th regional percentile and in the 90-95th United States percentile. The EPA defines the NATA cancer risk as “lifetime cancer risk from the inhalation of air toxics.” As these dangers plague the demographically low income, minority population of the Ironbound, it is important to understand the direct impact this can have on the lives of residents who already face so many other challenges.

When Agent Orange was produced in Newark, the Ironbound was populated by poor, minority groups. According to data from the 1969 census, Newark was composed of 52.2 percent Africa Americans and 12 percent Mexican Americans. About 35 percent of people in the area lived below the poverty level. 67.1 percent of those 25 years and over did not graduate high school and only 25.2 percent of men worked in white-collar occupations. 30 These statistics, in combination with testimony from plaintiffs who were part of the lawsuit against Diamond Alkali, help to paint a picture of what kind of people were working at the Diamond Alkali factory and therefore exposed to dangerous chemicals.

Despite the fact that by 1983, reporters, Newark residents, and the Environmental Protection Agency were all concerned with the state of the environment in Newark, it took years for any concrete change to happen. A combination of grassroots efforts and media exposure secured funding to test to soil at the Diamond Alkali site and in September of 1984, the site was classified as a Superfund site and added to the National Priorities List. In 1985, the off-site areas affected by the Diamond Alkali site were remediated through surface oil-removal, off-site streets were vacuumed to remove dioxin and contaminated soil was removed.31 However, the areas most directly affected by dioxin, the Passaic River and the factories on the banks of the river, were not cleaned up. Fifteen years after the initial discovery of dioxin in Newark, the EPA decided on a solution: to wall off and cap off the contaminated soil and debris leaving a six-acre mound amongst riverfront factories.32

When the EPA announced their intentions for addressing the Superfund site, many were extremely upset with the proposed solution and felt there was more that could be done. In fact, many have connected the lack of initiative to the location of the environmental disaster. Core activists like Arnold Cohen who fought to have the factory waste removed said “there elected officials, far from rushing to clean up one of the nation’s most densely populated square miles, turned away from a poor community in a poor city.” 33 Residents of the neighborhood expressed their feelings that politicians have shown no interest in helping the Newark community, nor have they been helpful in the fight to help clean up Newark. With a less than satisfactory solution presented by the EPA in 1998, Newark residents continue to suffer from their proximity to a contaminated environment. While there are still numerous environmental problems at the site, the three most relevant to the site are the National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA) cancer risk, the NATA respiratory hazard index, and the hazardous waste proximity. It is important to understand the overall health effects of the area in conjunction with current demographic data. Understanding the information in context will help to show the extent to which there continues to be environmental injustice in the Iron bound.34

While the environmental problems at the Diamond Alkali site are problematic on their own, the lack of action taken to rectify the situation can be understood when the demographics of the area are considered.. Within a quarter-mile radius from the Diamond Alkali plant lives a minority population in the 89th country-wide percentile, 82nd regional percentile, and 87th state percentile. In other words, only 11 percent of places in the country have a higher minority population than the Ironbound does. As discussed in the EPA report on environmental injustice, it is more common for minority communities to be affected, long term, by environmental injustice. 35 In addition to having a majority-minority population, the site is home to a low income population, residents who have less than a high school education and are linguistically isolated. 36 Low income communities often do not have the resources or political connections needed to make big changes happen quickly. Also important is the fact that many in the area are not only isolated from those in power because of their socioeconomic status, but they are isolated because they cannot speak English.37

The data supports the conclusion that people on this site are minorities, who often lack a high school education and suffer from the disadvantage of not speaking English. Understanding the population demographics of the area helps to explain why such the Diamond Alkali site continues to be a problem. The people who live closest to it, and are therefore impact the most, are people who cannot fight for themselves as well as other groups of people. A lack of education and the language barrier would be significant hurdles to overcome in their own right add the fact that these people are minority groups, and it’s a surprise anything has been done to try and rectify the problems brought about by Agent Orange.

Despite being an ocean apart, in the face of environmental injustice, grassroots movements have mobilized in both Newark and Vietnam to demand reparations for the damages brought about by Agent Orange. Grassroots movements in both places have used both protests and litigation in their quest for justice. While success in Newark and Vietnam is impacted by socioeconomic status and race, Newark residents do see more success than people in Vietnam. When researching litigation surrounding Agent Orange, cases filed by veterans, Newark residents and Vietnamese civilians all showcase the different ways the courts and chemical companies responded to suits filed against them. In this transnational history, the law showcases how different groups of people received different treatment based on their race and class. While much scholarship exists on the side of US veterans, 38 an extremely small amount of scholarship 38 covers either Newark or Vietnam. By looking at all three together, it becomes clear that in regards to compensation and assistance Newark residence have more in common with Vietnamese civilians than they do with United States servicemen and women.

Beginning in 1980 and continuing into the present day, there have been countless lawsuits brought to court dealing with Agent Orange. The first of these cases took place between 1980 and 1984. The first case, In re Agent Orange, was a class action lawsuit brought by US veterans who had served in Vietnam. Hundreds of veterans had joined together to sue seven chemical companies for damages and health related issues. By May of 1984, Chief Judge Weinstein, Chief Justice of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of NY, had agreed to allow the case to go to trial. The fact that Judge Weistein would have allowed the case to go to trial is extremely important as years later, he would deny the same opportunity to Vietnamese civilians who also tried to sue these chemical companies.39

Despite the fact that the case was to be allowed to go to trial, on May 6, the day before the trial was set to begin, the veterans and chemical companies reached a settlement in which the chemical companies agreed to pay out $180 million to those part of the lawsuit. This is the most chemical companies have ever agreed to pay in a lawsuit related to Agent Orange despite the fact that residents of Newark were affected by Agent Orange in the same way that veterans were. While the chemical companies settled, they did so without admitting any liability for the use of Agent Orange. In terms of future lawsuits, because this case was settled without the chemical companies admitting they were liable, anyone who would want to bring lawsuits against chemical companies in the future would be tasked with the burden of proving these chemical companies were liable.40

Due to the publicity veterans suing the chemical companies received, the federal government commissioned the New Jersey Agent Orange Commission. 41 As part of this commission, researchers were able to create a way to detect dioxin levels in the blood. Previously, they could only be detected in fat tissue. As part of discovery in the case of In re Agent Orange 1984, Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange had their blood tested for dioxin levels. Testing revealed that veterans, in comparison to a control group, were found to have higher levels of dioxin in their blood. This played a large role in the decision of the chemical companies to settle with veterans. 42 While this was an important factor, the status of “veteran” was also important demonstrated by the fact that Newark residents and Vietnamese civilians who also had high levels of dioxin in their blood did not get the same type of settlement. In addition, this commission resulted in the US federal government taking steps to help compensate its veterans.

Signed by President Clinton in 1991, the Agent Orange Act makes veterans who were exposed “on the ground” to Agent Orange eligible to receive treatment and compensation for conditions linked to the chemical- regardless of race or socioeconomic status. 43 This bill is so broad that it even covers presumptive conditions- conditions that have not been proven to have a connection to Agent Orange exposure. This bill covers all veterans who were in Vietnam when Agent Orange was sprayed- even if there is no evidence that they had been exposed to Agent Orange. This bill is important as it served to highlight the different treatment veterans received in comparison to Newark residents exposed to Agent Orange. While the US government felt a responsibility to its veterans, the same is not true for the poor, minority groups of Newark or the civilians of Vietnam.

Following the success veterans had in their suit, in addition to the creation of the Agent Orange Act, over 70 employees and residents of Newark banded together to sue the chemical company responsible for the production of Agent Orange. 44 In the lawsuit, employees and residents of Newark claimed to be suffering from a variety of illnesses linked to dioxin. Just like with the veterans, the company settled the case outside of court. The company agreed to pay out a settlement of $1 million but refused to admit liability for the production and use of Agent Orange. 45 While the company did agree to settle, the minimal amount of the settlement, especially in comparison to the settlement reached with veterans, indicates the importance of veterans in comparison to the residents of Newark. In addition, while news coverage gave the veterans help in their fight for justice, not such things happened for the residents of Newark. 46 It was not until recent years that the media began to devote attention to the environmental crisis in Newark, and their coverage focuses on the environment rather than the people living in the toxic environment.

While the veterans and residents of Newark sued chemical companies in the 1980s and 1990s, those in Vietnam had to first focus on rebuilding their lives following the end of the war in Vietnam. As time passed, many began to develop numerous kinds of diseases. Perhaps even more devastating, thousands of children were born with fatal or extreme congenital disabilities.47 While the Vietnamese government had asked and received some help from the United States when it came to cleaning up the environment, almost nothing was done to help the people suffering the side effects of Agent Orange exposure. In 2003, the Vietnam Association of the Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA) was created. This organization tried to help people using litigation, but they also provide medical care, rehabilitation services, and financial help for those affected by Agent Orange. Like Newark residents who used grassroots movements to fight for justice, those in Vietnam would use grassroots movements to provide life-saving care for those in need.48

In the 1990s, grassroots organizations came together to create Peace Villages which provide help for children born with disabilities due to Agent Orange. By 2011, eleven Peace Villages were created to provide medical and psychological help to those affected by Agent Orange. Peace Villages were created with the sole purpose of providing specified medical services and vocational education for disabled children and children born with deformities as a result of exposure to Agent Orange. Most Peace Villages are home to children born with defects caused by Agent Orange. In many cases, parents abandoned their kids in these villages because they were unable to care for them. In the Hoa Binh Peace Village which is located on the same grounds as a hospital, about 1.5 percent of babies born are still affected by Agent Orange. Many people in Vietnam have organized and come together to raise funds for these Peace Villages. Others volunteer their time, and those involved in the running of the Peace Villages have successfully lobbied the Vietnamese government for funds to help keep these Villages open.49

While many were involved in the creation and running of Peace Villages, others realized that taking legal action against the creators of Agent Orange could be a way for them to get compensation for the people and environment affected by toxic chemicals. In order to try and gain compensation for those affected by Agent Orange, the Vietnam Association for the Victims of Agent Orange filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of NY in Brooklyn against several US chemical companies in 2004. As both the veterans and the residents of Newark settled their cases outside of court, the VAVA would be tasked with proving the chemical companies were liable in the case of Agent Orange. VAVA brought the case to court under the Alien Tort Statute, which grants district courts jurisdiction over any civil action brought by an alien having to do with the violation of international law or a treaty of the United States. In this case, the plaintiffs sought monetary damages as well as help with environmental abatement and cleanup.50 Despite evidence linking the effects of Agent Orange to environmental damage and health risks, the Vietnamese had their case dismissed by Chief Judge Weinstein, the same judge that oversaw the lawsuit brought forward by US veterans in the 1980s.

There are several reasons why Judge Weinstein dismissed the case brought by VAVA that are explained using both domestic and international law. The Judge in the case ruled that because Agent Orange caused health problems that could be caused by a variety of other factors, they could not prove that it was Agent Orange that caused the health problems in this case. In regards to the environment, the Judge explained that because Agent Orange was used by the government during wartime to protect US troops, there was no issue of liability on the side of the chemical companies. Legally speaking, the chemical companies simply fulfilled a government contract, which is not illegal. The decision to use agent Orange was made by the government to help win a war, and therefore the Vietnamese did not have a legal leg to stand on.51

Despite the initial ruling on the case, VAVA filed an appeal for this case in 2007, displaying they were willing to do all they could to secure compensation for the Vietnamese suffering from Agent Orange. While an appeal was filed in 2007, the judges who heard the appeal upheld the original verdict that dismissed the case. In the appeal, the judges held that though Agent Orange contained dioxin, a known poison, there was no intent to harm humans when the chemical was used. This lack of intent meant that Agent Orange was a harmful herbicide, but not a chemical weapon. Without the status of a chemical weapon, the use of Agent Orange did not violate international law, and the case, therefore, was dismissed. Disheartened by the outcome in the appeals court, VAVA filed a petition with the US Supreme Court in 2009. The Supreme Court denied certiorari in 2009 much to the outrage of the Vietnamese.52

The lawsuits and outcomes of the lawsuits brought by residents of Newark and residents of Vietnam share several similarities in regards to an acknowledgment of liability, the nature of the lawsuits, and the desire for environmental injustice to be rectified. While communities of Newark and Vietnam affected by Agent Orange are composed of minority, low-income individuals, both groups of people came together with those of their community to fight for their right to compensation. In the fight for justice, leaders from both communities emerged and attempted to use the law to help those exposed to Agent Orange. Despite their best attempts, neither the residents of Newark nor the Vietnamese were able to get the courts to hold the chemical companies liable for the damage Agent Orange has done. Both groups used class-action lawsuits, hoping that the power of a group would help their case. Moreover, while those in Newark do get chemical companies to agree to a settlement, the amount they received was nothing in comparison to what awarded to veterans. The Vietnamese did not receive a settlement at all.

Juxtaposing the treatment veterans received to the lack of treatment civilians, both in Newark and Vietnam received, helps to show that there are things that can be done to help the people and environments exposed to Agent Orange. In studying the services available to US veterans affected by Agent Orange, it becomes clear that both physical and mental health is critical to those affected by Agent Orange. Also, the families of veterans affected by Agent Orange receive financial help to care for veterans suffering from exposure to the chemical. The cost of medical care is astronomical, and merely knowing that healthcare is covered is a huge deal. While veterans have fought hard for the financial assistance they now receive, those in Newark and Vietnam continue to be unsuccessful. Added to that, both those in Newark and Vietnam continue to live in environments contaminated by the chemical. For this reason, despite setbacks, grassroots movements are still fighting to help clean up the environment and help the people exposed to Agent Orange.

In Newark, legal battles between the government and chemical companies have delayed the cleanup of toxic sites that most affect poor communities. When it comes to cleaning up the river, the government of New Jersey claims that chemical companies that own properties that were used to contaminate the river need to pay for the cleanup. Chemical companies have tried to find legal loopholes to get out of paying for cleanup, which could cost billions of dollars. Even though the EPA declared 80-120 Lister Avenue a Superfund site in 1984, almost nothing has been done to rectify the issue. “This is exactly what we said was going to happen,” said advocate Ana Baptista. She grew up next door to a steel drum factory in Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood and now is an environmental policy professor at The New School. “Years ago, people were screaming at the state that there were these loopholes.”53

The initial solution proposed by the EPA to clean up the site at Lister Avenue cost millions of dollars and did little to solve the problem. In 1998, the EPA decided that rather than excavate or incinerate the soil and debris contaminated by Agent Orange, they would wall it off and cap it, leaving a sealed six-acre mound amid riverfront factories. In response to this solution, Arnold Cohen, who heads the Ironbound Committee Against Toxic Waste, declared that “they should put a monument to man’s stupidity there.” Despite the less than satisfactory solution, the plan did include a clause that gave Newark residents a reason to continue their fight to clean up the environment. As part of the plan implemented by the EPA, the burial plan had to be re-examined every two years in the hope that, eventually, technology would yield a cost-effective way of removing contaminated soil and debris. As a result, people in Newark continue to fight for solutions to the environmental issues in Newark. In contrast to the subpar plan used in Newark, as of April 2019, the United States government has agreed to help fund the cost to clean up dioxin in some regions of Vietnam. A ten-year project with an estimated cost of $183 million began at Bien Hoa, one of the main places used to store Agent Orange during the war. However, the site that is being cleaned up is located outside of Ho Chi Minh city and is the Bien Hoa airport. While it is a win that parts of contaminated sites are being cleaned up, the sites that most directly affect the poor of Vietnam are not being fixed with this plan. However, the Vietnamese took this cleanup as a win, and they continued to fight for the US to help clean up other toxic sites located throughout Vietnam.54

While the war in Vietnam took place decades ago, people in Vietnam and Newark continue to be affected by Agent Orange when it comes to the health of the environment. In both Newark and Vietnam, people have to deal with the problem of contaminated water sources, which in turn affects the fish in the water. For those those in Vietnam, the poor rely on the fish as a food source despite the fact that the Agent Orange in them is fatal. In Newark, fishing in the Passaic River continues to be outlawed. Additionally, the soil in both Newark and Vietnam tests high when it comes to dioxin levels. In both areas, the soil has transferred Agent Orange across different regions. Because of this, the danger of Agent Orange continues to spread despite the fact that dioxin had been outlawed since the 1980s. The last major environmental factor still affected by Agent Orange is the air itself. As dioxin particles can travel through the air, both people in Newark and Vietnam are at risk for Agent Orange exposure if they breathe in dioxin particles. While the environmental harm caused by Agent Orange is significant, the people affected by Agent Orange, the poor, minority groups, demonstrate that the creation and use of Agent Orange is also an environmental injustice issue. In both Vietnam and Newark, the poor continue to be most affected by Agent Orange. In Vietnam, the poor continue to be affected because of their reliance on food sources contaminated by Agent Orange and the fact that they live in areas in which Agent Orange is still present. In Newark, the Ironbound has several different areas that have been tested positive for Agent Orange- areas other than the former Diamond Alkali factory. Testing is still being done in Newark to see where exactly dioxin is- in the meantime, residents of the Ironbound continue to live in the area despite knowing if it is safe or not. While those affected mostly by Agent Orange may have been poor, minority groups, this has not stopped them from fighting for justice using both grassroots movements to bring change and awareness to environmental injustice.

In Vietnam, the people have come together to create Peace Villages to help care for children born with disabilities due to Agent Orange exposure. In addition, they have created charities for the victims as well as organizations, like VAVAO, that are tasked with lobbying the Vietnamese government for funds to help those affected by Agent Orange. In the United States, environmental activist groups have formed in Newark to help bring about real, and significant change for the environment in Newark. In addition, people have gathered together to lobby the government, participate with the EPA and organize protests to bring media attention to the environmental issues residents of Newark face. Even with grassroots organization of people in both Vietnam and Newark, residents of both places have turned to litigation as grassroots movements have not been enough to bring about the level of change needed. US veterans exposed to Agent Orange can serve as a juxtaposition to residents of Newark and Vietnam who tried to sue the same chemical companies veterans did with little success. While veterans saw success in their fight for justice, both people In Newark and Vietnam did not achieve the same level of success. Despite initial setbacks, both groups of people continue to keep an eye on the legal cases that are still developing surrounding the use of chemicals. Despite some efforts on the part of the United States to start the clean up process in both Newark and Vietnam, there is still much to be done. In terms of the environment, the water sources in both Vietnam and Newark need to be addressed. The air quality needs to be addressed- to do so, the factors contributing to low air quality must be fixed. Besides the environment, the people of Newark and Vietnam affected by Agent Orange need help too. Medical care to treat conditions caused by Agent Orange, both physically and mentally, is of the utmost importance. Despite the amazing work being done by activists in Vietnam and Newark, more people need to bring awareness to these issues as only pressure and the demand the US do better by its victims will bring about real and significant change.

Notes:

1 See figure one.

2 EJScreen Data

3 U.S. EPA. 1992. Guidelines for Exposure Assessment. Fed Reg 57:22887–22938

4 For a traditional military history, see William Buckingham, Operation Ranch Hand: The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia, 1961-1971 (Washington: Office of Air Force History, 1982); and Paul Cecil, Herbicidal Warfare: The Ranch Hand Project in Vietnam (New York: Praeger, 1986). For the social history, see Fred A. Wilcox Waiting For An Army to Die (1989: repr. Cabin John, MD: Seven Locks Press, 2011); and Jock McCulloch, The Politics of Agent Orange (Richmond, Australia: Heinemann Books, 1984); Wilbur Scott, Vietnam Veterans Since the War: The Politics of PTSD, Agent Orange, and the National Memorial, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004). For an environmental history, see David Zierler The Invention of Ecocide (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011). For a legal history, see Peter H. Schuck Agent Orange on Trial: Mass Toxic Disasters in the Courts (Belknap Press, 1987).

5 See, Ngo, A.D., et al. (2006). Association between Agent Orange and Birth Defects: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology 35.5: 220-30. Stellman, J.M., et al. (2003). The Extent and Patterns of Usage of Agent Orange and Other Herbicides in Vietnam. Nature 422:681-87. King, Pamela, Sodhi, Pamela, and Ridder, Anne. “The Use of Agent Orange in the Vietnam War and Its Effects on the Vietnamese People”. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2010. “Agent Orange in Newark: Time for a New Beginning.” Seton Hall Law Review 29, no. 1 (December 22, 1998).

6 See Wilcox, Fred A. “Waiting For an Army to Die.” Maryland: Seven Locks Press, 1984.

Fox, Diana Niblack. “One Significant Ghost: Agent Orange, Narratives of Trauma, Survival, and

Responsibility,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Washington, 2007.

Bui, Lan Thi Phuong. “When the Forest Became the Enemy” (Ph.D. diss,. Harvard University, 2003.

7 Blumenthal, Ralph. “Files Show Dioxin Makers Knew Of Hazards.” The New York Times, July, 1983.

8 Blumenthal, Ralph. “Files Show Dioxin Makers Knew Of Hazards.” The New York Times, July, 1983.

9 Vietnam v Dow Chemical, 517 F.3d 104, 109 (2d Cir. 2008).

10 Schecter, An; et al. (1995). “Agent Orange and the Vietnamese: The Persistence of Elevated Dioxin Levels in Human Tissues”. American Journal of Public Health. 85 (4): 516–522.

11 Stellman, Jeanne M; et al. (April 2003). “The Extent and Patterns of Usage of Agent Orange and Other Herbicides in Vietnam”. Nature. 422 (6933): 681–687

12 Rumbaut, Rubén G., A Legacy of War: Refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia (1996). Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in America, p. 315, S. Pedraza and R.G. Rumbaut, eds., Wadsworth, 1996 .

13 Ngo, Anh D., Richard Taylor, Christine L. Roberts, and Tuan V. Nguyen. “Association between Agent Orange and Birth Defects: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” International Journal of Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, 13 Feb. 2006. Web. 01 Nov. 2015.

14 Pham, Diem T. et al. “Predictors for Dioxin Accumulation in Residents Living in Da Nang and Bien Hoa, Vietnam, Many Years After Agent Orange Use.” Chemosphere Vol 118, January 2015 277-283.

15 Sagoli, Damir. “Vietnamese Families Still Battling the Aftermath of Agent Orange,” Independant April 4, 2017.

16 Olsay, Kenneth Ray and Morton, Lois Wright. “Long Term Fate of Agent Orange and Dioxin TCDD Contaminated Soils and Sediments in Vietnam Hotspots.” Journal of Soil Science Vol 9, no1 (2019).

17 Martin, Michael E. “Vietnamese Victims of Agent Orange and US-Vietnam Relations.” Library of

Congress Congressional Research Service. May 2009.

18 Gonzales, Sarah and Ye, Jenny. “Dirty Little Secrets: New Jersey’s Poorest Live Surrounded by

Contamination.” WNYC News. December 9, 2015.

19 Olsay, Kenneth Ray and Morton, Lois Wright. “Long Term Fate of Agent Orange and Dioxin TCDD Contaminated Soils and Sediments in Vietnam Hotspots.” Journal of Soil Science Vol 9, no1 (2019).

20 Moran, Michael. “Company Documents Reveal Agent Orange Producer Warned of Hazards in 1957.” AP News, December 27, 1988.

21 Bruno, Mary. “How We Poisoned the Passaic,” Grist, June 11, 2010.

22 Bruno, Mary. “How We Poisoned the Passaic,” Grist, June 11, 2010. See the legal testimony of Aldo Andreieni, Harry Heist and Michael Gordon. 258 N.J. Super. 167, 609 A.2d 440 (App. Div. 1992

23 Samson, Peter J. “Owners of a Defunct Chemical Plant that Produced Agent Orange,” UPI, June 6, 1983

24 Sampson, Peter J. “Owners of a Defunct Chemical Plant that Produced Agent Orange.” UPI News: June 6, 1983.

25 Bruno, Mary. “How We Poisoned the Passaic.” Grist. June 11, 2010.

26 EPA.org

27 Mansnerus, Laura. “Newark’s Toxic Bomb; Six Acres Foulded By Dioxin, Agent Orange’s Deadly

Byproduct, Reside in the Shadow of an Awakening Downtown.” The New York Time, November, 1998.

28 Barry, Jan. “Troubling Questions About Dioxin.” The New York Times, March, 1983.

29 The data compiled by EJscreen works in the following way. In analyzing the statistics for NATA Respiratory

Hazard index, the national percentile tells you what percent of the US population has an equal or lower value, meaning less potential exposure/risk/proximity to certain facilities.2 In other words, when considering the NATA respiratory hazard index, only 6% of other locations in the United States have even higher amounts of these environmental issues.

30 1970 Census of Population. US Department of Commerce: Social and Economic Statistics

Administration. Issued in May 1974.

31 Health Consultation, Diamond Alkali Company. 1996.

https://www.nj.gov/health/ceohs/documents/eohap/haz_sites/essex/newark/diamond_alkali/dahcfr.pdf

32 Mansnerus, Laura. “Newark’s Toxic Bomb; Six Acres Foulded By Dioxin, Agent Orange’s Deadly

Byproduct, Reside in the Shadow of an Awakening Downtown.” The New York Time, November, 1998.

33 Ibid.

34 This data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software. The software is able to calculate the environmental risks and demographic statistics of a specific area and contextualize the data in comparison to state percentiles, regional percentiles, and country-wide percentiles. By inputting the location of the Diamond Alkali factory, and creating a .25 mile buffer around the area, we can conclude that this area continues to expose Newark residents to toxic waste and materials.

35 U.S. EPA. 1992. Guidelines for Exposure Assessment. Fed Reg 57:22887–22938

36 According to the data, people in this area are in the 97th country-wide percentile, 98th regional percentile, and 99th state percentile for low-income populations. In addition, they are in the 83rd country-wide percentile, 71st regional percentile, and 74th state percentile when it comes to linguistic isolation and are in the 94th regional and country-wide (96th state) percentile having less than a high school education.

37 Ali, Mustafa S. “Environmental Injustice is Rising in the US and the Poor Pay the Price.” The Guardian, December, 2017. Erickson, Jim. “Targeting Minority, Low-Income Neighborhoods for Hazardous Waste Sites,” University of Michigan News January, 2016.

Cushing, Lara et al. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cumulative Environmental Health Impacts in California: Evidence From a Statewide Environmental Justice Screening Tool.” American Public Health Association (2015).

38 See footnote in the introduction for a better look at scholarship on this topic.

39 In re “Agent Orange” Prod. Liab. Litig., 304 F.Supp.2d 404, 424-31 (E.D.N.Y. 2004)

40 In re “Agent Orange” Product Liability Litigation, 580 F. Supp. 690 (E.D.N.Y. 1984)

41 N.J 208 Leg. Joint Resolution no 67. February 1980.

42 In re “Agent Orange” Product Liability Litigation, 580 F. Supp. 690 (E.D.N.Y. 1984)

43 H.R.556 – Agent Orange Act of 1991. 102nd Congress (1991-1992)

44 Diamond Shamrock Chemicals v. Aetna, 258 N.J. Super. 167 (N.J. Super. 1992): details of the lawsuit brought by Newark residents are present in this case as the chemical company tried to sue Aetna insurance to make them pay part of the settlement.

45 Joseph F. Sullivan, Special to The New York Times. 1992. “Company Settles Lawsuit Over Exposure to Dioxin: Diamond Shamrock Will Pay $1 Million.” The New York Times (1923-Current File), Jan 25, 29.

46 Dozens of articles discussing the fight of US veterans against chemical companies were published during the 1980s. In the 1990s, many who were not showing symptoms in the original lawsuit sued the chemical companies- once again, there were dozens of articles in nationally acclaimed newspapers that addressed the issue. Throughout the last 20 years, newspapers continue to publish articles about veterans and Agent Orange- mostly in relation to settlements and the level of care available to veterans affected by Agent Orange. While a simple search will yield these articles when it comes to the veterans, the same is not true for the residents of Newark or Vietnam. More so in the last 10 years articles have been published about these people. However these articles are usually titled something like “ The Forgotten Victims…” showing how neglected people in Newark and Vietnam have been when it comes to coverage about Agent Orange and its effects.

47 See figure two

48 Dainton, Debora. “The Vietnamese Association For Victims of Agent Orange.” MSAVLC, October,

2015.

49 Dainton, Deborah. “Hoa Binh Peace Village-Vietnam,” Medical and Scientific Aid for Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. October 21, 2015.

50 In re “Agent Orange” Prod. Liab. Litig., 304 F.Supp.2d 404, 424-31 (E.D.N.Y. 2004)

51 Vietnam v. Dow Chemical, 517 F.3d 104 (2d Cir. 2008)

52 King, Pamela S. “The Use of Agent Orange in the Vietnam War and its Effects on the Vietnamese

People.” (MA thesis, George Washington University: 2010).

53 Gonzalez, Sarah and Ye, Jenny. “ Dirty Little Secrets: New Jersey’s Poorest Live Surrounded by

Contamination. WNYC News December, 2015.

Brickley, Peg and Morgenson, Getchen. “Agent Orange’s Other Legacy- a $12 Billion Cleanup and a

Fight Over Who Pays.” The Wall Street Journal, December, 2018.

“Of Passaic River’s 105 Polluters, Only One Agreed to Pay for Cleanup.” North Jersey News, August,

2019.

54 Schoenberger, Sonya. “Victims Left Behind in Us Agent Orange Cleanup Efforts.” The Diplomat.

September 26,2019.

Primary Sources:

JAN BARRY. “Troubling Questions about Dioxin.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Sep 11, 1983. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/122248814?accountid=13626.

“Troubling Question about Dioxin,” is an article that was published in the New York Times in 1983. The article recounts that finding toxic dioxin levels in Newark was startling as no one ever thought to question how chemical plants would affect residents. The article also discusses the effects Agent Orange seemed to be having on veterans who were exposed to it in Vietnam despite government assurances that there was no danger from the chemical. The article will be useful in the development of my argument in several ways. First, it shows how no one questioned the production of dangerous chemicals in Newark among other places. This leads to the question- would people have cared if a chemical company proposed opening a factory in an affluent area? Second, the article explains that neither the federal government nor the EPA was concerned about the issue until an independent environmental activist wrote up his finding of dioxin levels in Newark. This shows how no attention was paid to the issue until a grassroots movement began to demand answers in regards to the problem. The idea of a grassroots movement being used to address the issue is something that comes up both in Newark and later in Vietnam and will help develop a transnational history between the two places. Last, the article explains the various ways reporters were shocked by the news that dioxin levels were found in Newark. Barry explains that no one in government ever expressed a concern about dioxin levels- in fact, government experts had repeatedly maintained that Agent Orange was safe. The fact that this issue is going to lead to individuals questioning the government will be used to help develop the section of my paper that deals with intent and knowledge when it comes to the creation of these plants in specific areas.

LAURA MANSNERUS. “Newark’s Toxic Tomb: Six Acres Fouled by Dioxin, Agent Orange’s Deadly Byproduct, Reside in the Shadow of an Awakening Downtown.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Nov 08, 1998. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/109958789?accountid=13626.

“Newark’s Toxic Bomb,” is an article that was published in the New York Times in 1998. Although published years after the production of Agent Orange, the article details the ways in which Newark residents attempted to address the problem of a toxic waste site and what the eventual solution was. There are three ways this source will be helpful in my paper. First, the source describes the disconnect between the residents of Newark and politicians. Interviews show that the residents of Newark do not feel as if the politicians in charge care about the well-being of Newark or its residents. This will help me develop a transnational history that showcases how race and class play a role in where environmental injustice takes place. Second, the article explains that the way Newark intended to deal with the toxic waste site was to simply seal it off- they weren’t actually going to fix anything. This too fits in with the idea of a transnational history in which lands in Vietnam were also simply left alone. Last, the article addresses the symposium arranged at Setton Hall in which Newark residents gathered to discuss the chemical waste issues in Newark. As I have a secondary source which did a write up of the event, this newspaper article gives another view of the symposium and the importance of it. This will help the development of my paper as it showcases a difference between the people of Newark and the people of Vietnam: the people of Newark have the opportunity to gather and demand a solution while the people of Vietnam do not.

Michael Moran. “Company Documents Reveal Agent Orange Producer Warned OF Hazards in 1957.” AP News December 27, 1988.

This newspaper article discusses how factory workers in Newark banded together to file a class-action lawsuit against Diamond Alkali. The plaintiffs hold that the company knew about the dangers of dioxin and did not put safety measures into place in order to save money. The article will be used to develop my argument in two ways. First, it is one of the only articles I’ve found, as early as 1988, that discusses the fact that factory workers were attempting to sue the chemical company. This will help make the argument that protests against veterans exposed to Agent Orange and protest about the fact that Newark workers were exposed to Agent Orange were not equal. The article will help to show that while people realized a toxic waste site was in Newark in 1983, they did not attempt to help the workers who were exposed to Agent Orange while they worked there. Second, the article will help establish the fact that workers did gather together to fight for compensation and will be used in conjunction with any court documents available to piece together their story. The story of Newark residents will then be analyzed in the context of both veterans and Vietnamese civilians.

RALPH BLUMENTHAL. “Files show Dioxin Makers Knew of Hazards: Court Records show Dioxin Makers Knew of Evidence of Health Hazards.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Jul 06, 1983. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/122116305?accountid=13626.

Published in the New York Times in 1983, this article discusses released documents that show that chemical companies knew of the dangers associated with Agent Orange and deliberately withheld this information from the government. The article states that the Dow Company told the government about the dangers of Agent Orange in 1970 and that the government stated this was the first time they were hearing about the issue. The article traces the history of Dow and its records about the effects of dioxin and explains when the government was given information about the dangers of dioxin. This article will help with the development of my argument in several ways. First, the article was written as a class-action suit brought by veterans needed to prove that the company knew about the dangers of dioxin and did not warn the government if they were to win their suit. The ramifications of this are enormous but also lead to many questions. If the government truly did not know about the effects of dioxin, does this absolve them of anything? Would they have done more research about the chemical if they were going to be using it in a European country? The article will help develop the argument that environmental injustice takes place so that people can make money- it also takes place in areas where the people can not look into the possible ramifications of a factory or plant. Second, the article addresses the issue of workers who worked in these factories and were exposed to dioxin. The article does not solely focus on the issue of veterans, it takes into account the damage done to workers who showed up to their jobs with no knowledge of the poison they were handling every day. Companies like Dow deliberately withheld information, not only from the government but from workers as well. And, while veterans were attempting to get compensation, no one was really talking about the Newark residents which help prove the argument that race and class are essential when it comes to the way environmental injustice is dealt with.

The Department of Veterans Affairs, Agent Orange Review: Information for Veterans who Served in Vietnam.” Vol 1 No 1, November 1982. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/agentorange/reviews/ao_newsletter_nov82.pdf

This report is the first in a series of reports written by the VA for veterans who were exposed to Agent Orange. The information in the report is helpful in identifying the effects of Agent Orange, but the fact that there is such a report is more important than what is in it. 1982 was the year that people first began to question the effects of dioxin and Agent Orange. This was the year the first newspaper articles were published on the topic and it’s the first year that the government admitted that Agent Orange may have been a problem. While both of those things are good, the fact that veterans are really the only group of people who are getting information and help for exposure to Agent Orange is troubling. This report, as well as the others, will help the development of my argument as veterans are going to be used as a contrast group in my paper. While veterans have access (although many would argue limited access) to information and help for exposure to Agent Orange, the same can not be said for residents of Newark or for Vietnamese civilians. This helps to develop a transnational history in which residents of Newark and people in Vietnam are both left in the dark when it comes to the dangers of the chemicals they were exposed to. Additionally, the people of Newark and Vietnam did not get the same access to healthcare that veterans did during this critical period.

Secondary Sources:

Committee on Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans and Agent Orange Exposure, and Institute of Medicine. Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans and Agent Orange Exposure. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011. Accessed October 6, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central.

This book documents the way in which the Institute of Medicine examined whether Blue Water Navy veterans were exposed to Agent Orange and are therefore deserving of benefits under the Agent Orange Act. The source will help in the development of my argument by allowing me to use veterans as a contrast to Newark residents and vietnamese people exposed to Agent Orange. While Navy veterans did not initially receive disability benefits, they too try and fight to receive help from the US government. Looking at how Veterans are treated by the government and Department of Veterans Affairs will provide a good contrast to the ways Newark residents and Vietnamese people were treated. My paper will then explore the reasons for the difference in treatment.

Frey, R. S. “Agent Orange and America at War in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.” Human Ecology Review 20, no. 1 (Summer, 2013): 1-10,67. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/docview/1511435985?accountid=13626.

This source looks at the environmental impacts and consequences of militarism and the use of Agent Orange in the Vietnam War. The articles explores the origins of Agent Orange, the scope and scale of how it was used by the military, and the environmental, health and economic consequences of Agent Orange. Frey makes the argument that the herbicide was used due to geopolitical and domestic tensions and that there are still recent developments resulting from the use of Agent Orange. This article will help in the development of my paper for several reasons. First, it nicely outlines the environmental injustice that took place because of Agent Orange in Vietnam. Second, it explores the reasons why Agent Orange was used which will help develop my argument that explores how race and class played a role in environmental justice both in Vietnam and Newark.

MARTINI, EDWIN A. Agent Orange: History, Science, and the Politics of Uncertainty. University of Massachusetts Press, 2012. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/stable/j.ctt5vk4s2.

This book explores the numerous effects of Agent Orange on the environment, civilian population and troops in Vietnam. This book offers a comprehensive look at the story behind the use of Agent Orange and answers several important questions. This book will be helpful in my paper because the book explores what exactly the US government knew about the harmful effects of Agent Orange, looks at what should be done for both US soldiers and Vietnamese victims, and explores the controversy that continues to surround the use of Agent Orange. This source seems to be a really good reference guide for “background information,” and will allow me to see how another scholar approached the history of Agent Orange while I try and fill in some of the missing pieces and connect it to the development of Agent Orange in Newark.

PALMER, MICHAEL G. “The Case of Agent Orange.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 29, no. 1 (2007): 172-95. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/stable/25798819.

In 2004, claims were filed on behalf of Vietnamese people who suffered from Agent Orange in the New York District Court. Although the claims were dismissed, this article offers a commentary on the case in order to explore the broader themes of politics, international law, and the accommodation of individuals during war. This article will be very useful in my paper as it presents a comprehensive view of the lawsuit made by Vietnamese people in regards to Agent Orange. As I hope to show that both the people of Newark and the people of Vietnam attempt to hold chemical companies accountable for their actions, this article does a good job of providing commentary on the key case brought up by Vietnamse victims.

Tirza S. Wahrman, “Agent Orange in Newark: Time for a New Beginning,” Seton Hall Law Review 29, no. 1 (1998): 89-94.

This article looks at the use of Agent Orange in Newark and the way that the people of Newark came together to demand change. So far, this is really the only secondary source I’ve found that discusses the use of Agent Orange in Newark. This source will help in my paper as it will help supplement information I find through primary sources and it also provides a succinct description of the environmental problems Agent Orange had on the Newark environment.

Image Analysis:

Data Analysis:

The Diamond Alkali site is marked by the chemical Dioxin which was used to produce Agent Orange in Newark during the Vietnam War. In 1984, the site was listed on the Superfund National Priorities List as Dioxin, pesticides and other chemicals were found in the soil and water. In addition, metals and pesticides were found in the sediment in the Lower Passaic River. While there are still numerous environmental problems at the site, the three most relevant to the site are the National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA) cancer risk, the NATA respiratory hazard index, and the hazardous waste proximity. It is important to understand the overall health effects of the area in conjunction with current demographic data. Understanding the information in context will help to show the extent to which there continues to be environmental racism in the Iron bound. This data was obtained through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Environmental Justice (EJ) Screen software. The software is able to calculate the environmental risks and demographic statistics of a specific area and contextualize the data in comparison to state percentiles, regional percentiles, and country-wide percentiles. By inputting the location of the Diamond Alkali factory, and creating a .25 mile buffer around the area, we can conclude that this area continues to expose Newark residents to toxic waste and materials.