The Struggle In Front of Toxics:

The Unequal Hazardous Waste Distribution in Northeast Detroit (1974-2021)

by Jui-Cheng Ryan Wu

Site Description:

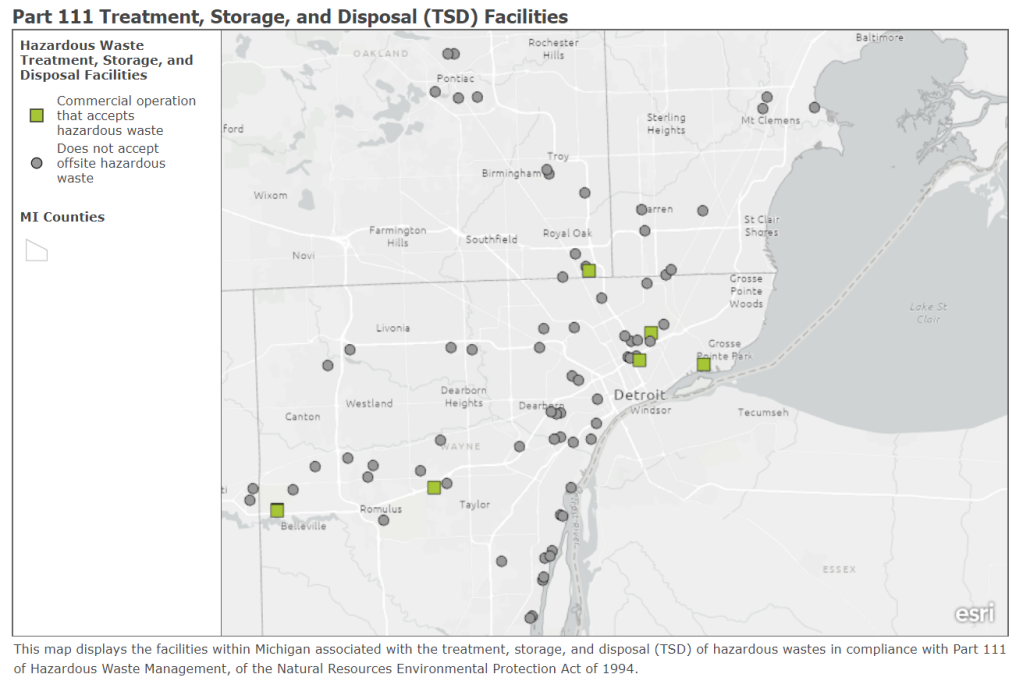

Since the mid-19th century, Detroit has been a center of industries and commerce of Michigan, it’s significance especially escalated as the Automobile industry took off in the 1910s. Environmental contamination comes with the thriving industries continuing to the current era. One shocking news in January of 2020 catches the attention of the less wealthy societies, as the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) approved U.S. Ecology’s permit to increase its storage of toxic waste nine folds. In detail, The plant has permission to treat 144,000 gallons of toxic and industrial chemicals per day, including arsenic, cyanide, mercury, PCBs, and PFAS, that are dumped into the city’s sewer system. It soon raises the attention of the public on environmental racism. According to the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, 65% of people living within three miles of a commercial hazardous waste site in Michigan are people of color, despite being only 25% of the state’s population; and the lack of representation of the local community give manufacturers an easy pass for disposal. Activists on environmental justice joined with locals and quickly started the negotiation with the EGLE. As this is still an ongoing crisis. I would like to look into the inequality of power behind the scene, and what resisting action has been taken that gives pressure to the officials especially in this case. Since environmental injustice is not a new subject for the area, I also want to understand what the local organizations have done addressing the inequality before this clash. The outcome could serve as a reference for the people across the States that are urgently facing similar environmental problems.

Introduction: Hot Metallic Summer

On a hot summer day in late June 2019, people with protest signs on their hands started to shown up and gathered on the main street of Eastern Market [1], a popular area with several historical marketplace, within a short walking distance from the Detroit City Hall. For just a brief time, the crowd quickly grew up to around 50 people, attracted attention from all the pedestrians passing by. Sunlight reflected by the nearby 3-story neoclassical brick building projected a warm red hue on them. Not many emotions were written on their faces that belong to a variety of races and ages. Not much conversation was happening between them either, even though we could tell from their interaction that this group of people might already knew each other. The noise of a mobile speaker turned on broke out in the crowd, followed by slogans from the shouting protesters. The group of people started to march down the popular street. “Deny the US Ecology permit!” yielded intensely by a mid-age African American with a microphone on his hand.

This protest was not the first time for these Northeast Detroiters, a group of locals, activists and political leaders from the Detroit neighborhood, just by the border of the neighboring city of Hamtramck. This is a demographically diverse neighborhood with Arabic Muslims, Hispanics, African American, and Caucasian. They are all united together — to fight against US Ecology (USE), a verbally harmless commercial waste management company that was anything but being eco-friendly. The hazardous waste treater proposed to expand its Detroit North treatment plant and its storage facilities, which handled a major portion of the hazardous waste from the region since the 1970s [2]. This treatment plant had suffered from an inadequate safety record ever since; mercury, arsenic, and cyanide were being released into the neighborhood’s sewer system [3], threatened the surrounding environment and the health of the locals. As early as in the first half of 2016, rumors on US Ecology’s outrageous capacity expanding proposal started to spread among the neighborhoods. This quickly elevated the anger of the local community, and the coalition opposing the expansion was formed. Some of the earliest protests could be dated back to April of 2016. The rally that happened in June of 2019 was an eye-catching success, but what these protestors would never know back then was, the darkest day had not even arrived yet.

“Why us?” This is likely to be the biggest and the most urgent question wondered by the furious residents. The event happening in Northeast Detroit is just a typical story of one of the many hazardous waste sites in Michigan. These ever-growing, spatially harsh and filthy industrial land further cut through the environment in these resource-lacking neighborhoods, which are already lacking essential softness from the greeneries. The director of the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, Michelle Martinez, even described this event as an environmental racism [4]. “Michigan’s low-income communities of color and poor are being intentionally targeted when it comes to hazardous waste placement”, he said.

Likewise, the USE Detroit North tragedy is not simply just formed with one or two factors. As this essay digs down deeper by contrasting this area with other nearby neighborhoods which stays unaffected by any hazardous waste problems, and compare with similar historical events, we will be able to understand the driving forces behind the issue in a more thorough perspective. This essay is intended to find out why these disadvantaged were being targeted, and what was keeping their voice from being heard.

The Detroit North Glitch

The whole event of Detroit North Treatment plant expansion originated in 2012, when the centralized industrial wastes treater — US Ecology (USE) made an agreement with PVS Chemicals, to acquire all the Dynecol stock and existing facilities. The current treatment plant and its storage started operation in 1974 [5] and is one of the 14 treatment plants in Michigan that handles the industrial liquid hazardous waste in the region, predominantly the types of acids generated from the steel industry [6]. It received its previous 10-year operating license in 2007, and with the purchase, the license transferred with the facility onto the operation of USE in 2012. The acquisition, for USE, was an important growth in terms of their geographical footprint, as the former chief operating officer James Baumgardner put it as a “physical presence in a Key industrial market”. The plant generates between $9 to $12 million dollar revenue annually from the last several years ahead of the purchase [7]. USE started off planning the expansion proposal as soon as it got its hand on their new facility, long before the expiration date of its current license. In 2015, Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), formerly known as the Michigan Department of Environment Quality (MDEQ), released a draft license for the USE Detroit North, and opened it for public comments. It quickly got the locals’ attention and their strong opposition; one protest after another were held against the proposal. Eventually, the public hearing period got extended twice into 2018 under the pressure, while the license went onto a further review and investigation under the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, on January 29th, 2020, EGLE passed the long-proposed expansion by the US Ecology. Alongside all the facilities from the 2012 purchase, another two newly proposed annex building were permitted, the allowable capacity of the treatment plant was expanded by nine folds [8].

No matter how much the locals disliked the idea of USE expansion, from the standpoint of the governmental agencies, an application can only be denied when the proposal did not meet the requirement of laws and regulations. In this case, EGLE did not have the authority to deny the application from USE simply based on public opposition. According to the summary report given by the Michigan Government, if the renewal and expansion application did not provision a violation of the regulations, it would only be stopped when a technical comment was provided to prove its violation of laws [9]. In other words, the opinion of locals was not directly influential in the decision process of the 2020 permission.

Moving on to the topic of the effectiveness of regulations. Among all the industrial facilities, the hazardous waste treatment plant is one of the most difficult one to be regulated due to the wide variety of materials it collected. By processing the industrial waste, it reduced the harm given by the hazardous waste on the city’s sewer system and the affiliated wastewater treatment plant. Even though the maximum levels of toxic chemicals in industrial wastewater discharges were monitored by the governmental agencies, regular inspections only happened on a ridiculously infrequent rate every quarterly. Moreover, even if a discharge violation was discovered, it often would not threaten the treatment plant’s license. Only a requirement of correction would be issued to them with a fine [10]; too little, too harmless to constraint a monster like USE.

“I’ve been looking at it since the mid-1990s, when it was really bad,” said Jodi Peace, an industrial pretreatment specialist from DEQ during an interview with the Detroit Free Press. Looking at the record, this formerly Dynecol treatment plant was better in recent days compared to the years past, when it was one of the treaters who were frequently shown in the list of significant violations. In 2013, Detroit Water and Sewerage Department went on an inspection after being reported by locals and found out a mysterious layer of foam built up from a drainage basin near the facility. Meanwhile, in the first half decade of 2010s, USE already got involved with over 150 violations. Some of the most significant examples included the mercury level that exceeded 3.5 times then permitted in their wastewater, in October 2012; and the arsenic level that exceeded an outrageous 350 times then permitted, in December 2010 [11].

The Clean Neighbor

Approximately 20 miles north from the clash and chaos, sits the City of Bloomfield Hills, a quiet neighborhood surrounded by nature, and the home of some 4000 residents. It is also the location of three beautiful country clubs, and some housing design masterpieces done by well-known architect Frank Lloyd Wright, despite its relatively compact geography (5.04 sq-miles). The cloud that shadowed the Northeast Detroit neighborhood remained distant, neither were we seeing the massive and harsh looking industrial waste treatment facilities, nor were we hearing trucks roaring through the main street with trailer containers. The towns nearest hazardous waste treatment plant were in the nearby town of troy. Luckily, that was not something for them to be worried about. Unlike the troublesome USE facilities, this was one of the domestic waste treaters operated by SOCRRA that only served the local. In the first half of 2020, this operating location ended its service, and the service was transferred to another three alternative waste management sites [12]. The unwelcomed facility that was already out of town got pushed further away southward, towards the direction of Detroit.

In fact, Bloomfield Hills had long been a community that was well known for its natural environment, which provided the privacy and quietness that most of the people desired. Benefited from its prime location of the relatively short commute to Detroit city center, this rural residential area had attracted many of those who held professional or executive positions of authority in the automobile industry and other Fortune 500 businesses [13]. Since its establishment in the 1920s, this wooded little town that came out of the historical Oakland County farmland had been kept free from any industrial threats and was frequently ranked as one of the top 5 wealthiest cities in the US.

Factor to the Unfairness

In the last couple years, the Detroit North US Ecology expansion crisis has been accused many times by the locals and environmental activists as an environmental injustice and has even been described as an environmental racism. In contrast to Bloomfield Hill, a place with a much lower population density, the highly populated Northeast Detroit neighborhood did not escape from the sad fate of living and dealing with industrial wastes. Quoting from Nick Leonard from the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, 65 percent of the people living within three miles of a commercial hazardous waste treater in Michigan are people of color, despite being only 25 percent of the state’s population [14]. It is an unfair distribution that has an obvious demographic target.

Located in an old industrial district, the neighborhood around the USE Detroit North site was formed with a diverse group of residents, including African Americans, Middle East Muslims. White population only took 16 percent of the total population, unlike the town of Bloomfield Hill where up to 87 percent of the residents were white. In terms of economic factors, the per- capita income of the northern town easily surpassed the Detroit city neighborhood by six times, at $79,000 annually. Low as only 42 percent of those urban residents had ever tried to attend a college degree [15], which marked a significant disadvantage when it comes to circumstances that needed their voice to be embraced in the public. Bloomfield Hills on the other hand, the residents had an absolute superiority in terms of influence. As a mostly privileged and prestigious group of people, it was considerably easier for them to alter any plans or policies directly from the decision-making level, whether in a private or a governmental scenario.

Hazardous waste treatment sites, though could be legal and harmless if it was well supervised, was still one of the most unwelcomed facilities to the mind of the general public. From a legal standpoint, the competent authorities were just doing their job, passing a seemingly eligible application. But the will of the locals’ opinion got totally excluded from the decision-making process publicly. Picking a location with less powerful opposition became an obvious option for these waste management companies, when they compared angering several Corporations and financial groups all at once, with offending just some vulnerable disadvantaged individuals.

USE Detroit North was just one of the industrial waste treatment plants in the less wealthy urban area in Detroit and its neighboring towns [16]. Most of the facilities ended up picking more populated locations instead of other relatively more remote areas where they would not encountered as much of intense opposition.

Although several coalitions joined by locals and activists had already held countless protests, their influence eventually did not change the final decision of the governmental agencies, like a lost child in the rule of law society. Even though the USE Detroit North facility had already been proven to be the origin of many violations chronologically, competent authorities such as the EGLE and EPA were not effective in applying long term correction. It was even more ironic that the ineffective path of providing technical comment was the only legal way for the locals. Without a backup from any social resources, public’s attention, or political influencers to form a strong enough public pressure, the opposition from these coalitions were destined to anything but a success.

Precedents

From the lens of the USE Detroit North expansion, and looking back to history, there were many past events that had a similar identity. In terms of protesting, one of the earliest examples was the Warren County environmental justice movement, which took place in North Carolina, 1982. As a home of a majority black and unprivileged residents, the county in the rural area was chosen to be the dumping site of over 60000 tons of PCBs contaminated soil, potentially threatened the safety of drinking water. It quickly caught the attention of the media when intense protests happened one after another, and furious locals lied down on the roads to physically blocked the roadway to the landfill. At first, the media’s attitude was biasedly leaning toward the government, but as the none-stop protests went on, the whole clearer story eventually still spread out thoroughly to the entire country. The popularity of this event quickly elevated on a nationwide scale. Even though the opposition failed at the end, it inspired and gave hope to the people over the country who had faced similar situations, on the possible actions to fight the unwanted. Compared to the Northeast Detroit story, the fight given by Warren County residents was relatively short, protests only lasted about six weeks. Unlike the 5 year-long runs in Detroit, it was a large-scale outburst that quickly caught the attention of the public.

[17]

Another precedent was Malibu portrayed by the well-known writer Make Davis. It depicted the unfairness of the resource distribution between two neighboring towns, Malibu and Westlake, which both faced the same problem –fire. Malibu, the beautiful coastal town, and the retreat of the privileged in the region. It was also the center of large-scale wildfire that, from the average since 1930, happened around twice in a decade periodically. These were not just regular fires but were natural firestorms that raged over 10,000 acres at a single time. Regardless the recurring firestorms were seen by many as a way the local environment system worked, the fire department kept throwing in all the available resources in the entire region and even from other states, to fight an ever-losing combat that aimed to protect the property of the wealthy locals. Westlake, on the other hand, was facing another kind of catastrophic fire. It had the highest urban fire incident in the country, especially in the downtown area where a majority residents of the tenement were Hispanic. Many aging tenements and apartment-hotels constructed in the early 1900s already had records of frequent fires. Unfortunately, the town’s fire department was constantly running under resource and manpower shortages. One of the two fire stations in town even received over 20,000 emergency calls in 1993 alone. Many lives of the poor residents were lost each year. But limited by the “severely understaffed” situation, the fire department cannot even reinforce the fire safety regulation onto those aging illegal tenements [18]. Just like the Detroit North neighborhood, the unprivileged group were always the ignored one by the entire society and were more likely to be the one sacrificed.

Environmental justice movement has already gone through a long way since then. Looking back to the entire event of the Detroit North expansion controversy, the locals were not alone compared to the previous examples, they received immediate help from several environmental justice activist groups back when the draft proposal was announced by the EGLE in 2015. They were even joined by the Detroit Workers’ Voice, a local Marxist-Leninist study group, that untypically got involved because of the working-class demographic background of the area [19].

Conclusion

The summer 2019 protest at the main street of East Market historical district was not the first, not the last, but one in a series of many protests launched against the expansion project. These events were held in many other locations, intended to grab the attention of people from different areas, and increased the exposure of this issue. Their fight significantly extended the application review period. In early February of 2020, not long after the USE application was passed, another protest took place directly around the Detroit North treatment plant. But they were not able to stop the truck loaded full of mercury, arsenic, and other heavy metals to enter the facility. Dust was brought up by the trucks as they raged through the plantless neighborhood street.

In this environmental justice movement, the opinions of the locals were vastly ignored in the decision-making process, ignored by the government agencies, the law, and the whole political system. The current system failed to take those people who got affected into account, when it logically should be the main concern in this type of development. Even though there were already over a hundred cases of violation, long term corrections were never implemented effectively, and these cases as technical evidence were again ignored by EGLE during the review of the application. Majority of these urban neighborhood residents were also the disadvantaged group of people in the working class, who had relatively much fewer public influences and resources; this is the factor that made them vulnerable and became the easy target for commercial waste management giants like USE.

This movement as a tragic example, could be a reference in the future of making the decisional process farer. Despite the inevitable advantage gap between the rich and the poor, there was still a long way to go in terms of letting all the decisions be made unbiased: based on how many people a development program could affect, on its geological features, on its environmental impact and so on. Ways society can improve its fairness in ensuring the rights of the disadvantaged, is a crucial subject that deserves everyone’s attention.

Endnotes

[1] Anthony Lanzilote, “Group rallies against expansion of waste facility near Detroit-Hamtramck border”, The Detroit News, last modified: June 29, 2019

[2] Michigan Government staff, “US Ecology Detroit North (Formerly Dynecol),” Michigan Government, April 15, 2019

[3] Keith Matheny, “US Ecology’s permit violations anger Detroit neighbors,” Detroit Free Press, November 16, 2016

[4] Christine Ferretti, “Groups Urge Protection from ‘Environmental Racism’ in Hazardous Waste Placement,” The Detroit News, August 3, 2020

[5] US Ecology staff, “US Ecology, Inc. to Purchase Waste Treatment and Storage Facility” US Ecology Press Release, May 21, 2012

[6] Michigan Government staff, “US Ecology Detroit North (Formerly Dynecol)”, Michigan Government, April 15, 2019

[7] US Ecology staff, “US Ecology, Inc. to Purchase Waste Treatment and Storage Facility” US Ecology Press Release, May 21, 2012

[8] Steve Neavling, “Expansion of Hazardous Waste Plant in Detroit Smacks of ‘Environmental Racism,’ Rep. Robinson Says,” Detroit Metro Times, October 18, 2021

[9] Michigan Government staff, “US Ecology Detroit North Frequently Asked Questions”, Michigan Government, April 2019

[10] Michigan Government staff, “US Ecology Detroit North Frequently Asked Questions”, Michigan Government, April 2019

[11] Keith Matheny, “US Ecology’s permit violations anger Detroit neighbors,” Detroit Free Press, November 16, 2016

[12] Bloomfield Hills city hall staff, “Hazardous Waste”, Bloomfield Hills City Hall, last updated 2020

[13] Bloomfield Hills city hall staff, “About the Community”, Bloomfield Hills City Hall, last updated 2021

[14] Christine Ferretti, “Groups Urge Protection from ‘Environmental Racism’ in Hazardous Waste Placement,” The Detroit News, August 3, 2020

[15] Census 2010, accessed on Dec 10, 2021

[16] ArcGis, “Part 111 Treatment, Storage, and Disposal Facilities”, ArcGis, accessed on Dec 8, 2021

[17] Brian Palmer, “The History of Environmental Justice in Five Minutes”, NRDC, May 18, 2016

[18] Mike Davis, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn, Oxford Journals, Oxford University Press, Environmental History Review 19, No. 2, (1995)

[19] Detroit Workers Voice, “Calling the Society to Stop US Ecology’s Expansion Permission” Detroit Workers Voice, April 11, 2016

Primary Sources:

NOTICE OF FINAL DECISION: Approval of Hazardous Waste Management Facility Operating License US Ecology, Inc., Detroit North MID 074 259 565

This is the original document (Notice) from EGLE, regarding the expansion permission of US Ecology Detroit North plant, on January 29th, 2020. It includes details of US Ecology’s responsibility and requirements. Some frequently asked questions are attached with answers in this document too. This document is a reliable primary resource that explains the whole event, the changes made with this permission, and some general background information.

COALITION TO OPPOSE THE EXPANSION OF THE US ECOLOGY

https://coalitionstopuse.weebly.com/

This is the official website of the environmental justice coalition about our site, which includes all the updates and record of actions in either writing or imaging formats. The website also includes a lot of references in scientific studies on its resource page. This is a valuable and reliable primary source to keep track of the opponents in this environmental justice event.

Detroit Worker’s Voice, calling the society to stop US Ecology’s expansion permission

This is a document/poster on the early action against the expansion of the US Ecology Detroit North site, confusingly from the Detroit Workers’ Voice (Detroit Marxist-Leninist study group). They were calling for a march on April 16th, 2016, to oppose the expansion proposal of the US Ecology. This poster cited many sources from the Coalition’s website, and even included their website at the very bottom. From this source, we could probably specify more on the background of the opponent of this Coalition.

Expansion of Hazardous Waste Plant in Detroit Smacks of ‘Environmental Racism,’ Rep. Robinson Says. Detroit Metro Times. 1/31/2020

This is a news report on the day after the capacity expansion of the US Ecology Detroit North plant was permitted. It portrays the reaction of the locals toward this issue. This primary source could provide us a glance about the atmosphere of the community at that time.

Groups Urge Protection From Environmental Racism in Hazardous Waste Placement. The Detroit News. 8/3/2020

This is a report of the action these locals and the environmental activists do at the moment to try to push back the decision. The second half of the news report also included their point of view and some existing conditions at the time that they think are totally unfair which needed to be changed.

Secondary Sources:

This is a 90 page study on the environmental justice movements, about its history, theory, and its comparison with the human right movement. Done by Mary Hennessey, from University of Michigan. There are 20 pages (p39-58) in chapter 5 that focuses on the environmental justice movement in the Detroit area, which would provide us clear context of the history and examples of Detroit locals defending their homeland from further contamination. Even though it did not directly address our site in Northeast Detroit near the Hamtramck border, it would still provide us the background of the activists’ action in this area with the several precedents it includes.

US ecology Detroit North summary from Michigan Government

US ecology Detroit North FAQ from Michigan Government

These two above are the information and the FAQ regarding the US Ecology Detroit North Plant, done by the Michigan Government. It provides information on the history of the site, types of hazardous waste it processes in detail, and legal ways for the local residents to act against the treatment plant expansion.

US Ecology’s Permit Violations Anger Detroit Neighbors. Detroit Free Press. 2016

This report in 2016 discovered the facility on our site exceeded allowable discharge limits more than 150 times between 2010 and 2016. Mercury, arsenic, and cyanide were among those chemicals being released into the city sewer system at levels above the maximum limit”. This is a source that can provide us a clear image of how the US Ecology Detroit North plant is threatening the health of nearby residents, contaminating the local environment. This is also one of the earliest news reports that reveals the proposal of US Ecology that tried to expand this treatment plant’s capacity.

Image Analysis:

FOCAL POINT: Write down and describe the first site in the image where your eyes are drawn to.

I first saw the mid-age caucasian guy at the center with a black suit. He locked his arms with his two fellas on his left and right, seemingly like the leader of the activity. Even though he is wearing a nice looking suit, what is being worn inside is just a polo shirt that does not fit that well with its exterior, which indicates that he is probably not in the elite level that cares a lot on their outfit, but more of an unprivileged civilian.

DIRECTION OF MOVEMENT WITHIN THE PICTURE FRAME: Note where your eyes are drawn to next, traveling from one place to another across the image. See if you can create a narrative from the string of visual scenes and relationships among component parts. What might the progression of visual elements mean?

Then my attention is moved to the two people by his side. The one on the front left of the photo is an African American, presumably at around the age of 30 by looking at his skin smoothness. He is wearing a very casual white shirt inside a down jacket, this outfit is like a normal pedestrian. This might indicate that the young locals did care about this environmental justice movement and participated themself to this event. The other guy who locked his arm with the mid-age caucasian looks like a elderly muslim from the Middle east, he is wearing traditional style cloths and hat to attend this event. This gives a hint on the ethnical formation of the local population, as the three main characters in this photo are three distinctive races. Then my attention moved to the surrounding environment. There are some shipping containers in the far background, which suggests that this area is more industrialized and harsher than the average neighborhood as there are no greeneries in the frame.

SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS: Look to see if there are any spatial divisions in the image that reflect different zones of activity.

There are two zones in this photograph. This first is the three people in the front that takes over half of the frame, the second zone is the other participants in the background. Because of the angle the picture is taken, we can not clearly identify how many people have actually attended this event; we can only count three people in the background from this limited perspective. One of them is a mid-age Indian who is holding the sign, the other two individuals did not reveal themself enough in this photo to be identified.

COLOR: Note which features share the same color. Which ones are brightest, darkest, and dimmest. Can you make any judgments about these differences, including how the elements may be understood in relation to the others?

The most vibrant and contrast-rich part of the image is definitely the middle, where the three main characters are. The Sky background is almost overexposed, but also gives a hint of the cloudy days with the soft lighting it projects on these figures evenly. The brightness in this photo did not differentiate any figure significantly more than the others.

SCALE/SIZE: Compare the sizes of the various visual elements. Larger size generally correlates with greater importance.

Focus is clearly on the three people in the front as they took up about half of the frame. They are much bigger than the people in the background, which suggests that they might be the community leaders of this event or some important figure in this movement.

CONTRASTS: Note how some visual elements play off each other. These contrasts serve to accentuate differences and/or exaggerate the separate qualities of each. Conversely, little contrast can communicate likeness or similarity.

The plain cloudy sky was a pretty good contrast to the mood of the three people in the front, who looked very serious with intense facial expressions. It demonstrated the feeling of these people who are under the pressure of the incoming toxic waste.

INDIVIDUAL ACTORS & DETAILS: Write down any other details that don’t seem to fit a pattern yet seem important for understanding the image.

Everyone looks like they belong to this scene.

ABSENCES: Can you think of something that is conspicuously missing from the picture?

There are no females and kids included in this picture, it could just be the perspective of this shot that coincidently excluded these two types of people since this is a protest launched by the local community.

VALUES & MEANINGS: List some of the values you think the image maker is expressing through these visual relationships and elements. Try to state a takeaway message or two that you can then verify with other sources.

This image clearly portrays the anger and the anxiety of the local Detroiters on the US Ecology expansion. It shows the idea that this threat of environmental pollution really unites the different races living in this community to come together and fight for their own right. On the other hand, it shows the problem of the lack of representation of their voice in the governmental decision making class, which pushes them to go on the street with no other choices.

WHERE TO GO NEXT: List other sources you can turn to find out more information about the image.

- The Detroit workers voice

- US Ecology Detroit North plant 2020 expansion permission